TO THE EDITOR

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a complex, multifactorial chronic metabolic disorder representing the most prevalent form of diabetes, and accounts for approximately 90%-95% of diabetic cases worldwide[1]. The global burden of T2DM is growing, with worldwide projections indicating 783 million patients by 2045[2]. Unlike type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2DM patients are characterized by multiple comorbidities and premature mortality due to cardiorenal-metabolic complications, such as diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetic nephropathy caused by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, accelerated fatty acid (FA) oxidation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, endothelial dysfunction, and hyperlipidemia[3]. Long-term hyperglycemia and high saturated FA (SFA) concentrations critically suppress insulin secretion, induce pancreatic β-cell apoptosis, and decrease the number of normal functioning pancreatic β cells[3]. Therefore, maintaining pancreatic β-cell survival and improving functional pancreatic β-cells are the primary therapeutic strategies for the clinical management of T2DM[1,4].

ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM STRESS-INDUCED AUTOPHAGY AND APOPTOSIS IN VARIOUS ORGANS

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress can result from various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as amino acid mutations, nutrient deprivation due to hypoxia, and increased exotoxin levels after exposure to pathogens or inflammatory stimuli. Ramos-Lopez et al[5] reported a critical link between DNA methylation signatures of ER stress genes and metabolic dysregulations such as adiposity and insulin resistance. Under cellular stress conditions, the ER initiates a complex signaling cascade known as the unfolded protein response (UPR), which stimulates a set of transcriptional and translational events to restore ER homeostasis. The short-term effects of ER stress include dysregulation of normal insulin synthesis and secretion leading to β-cell dysfunction, triggering ER-associated degradation of proteins, and autophagy. Autophagy is the major lysosomal degradation pathway essential to organelle homeostasis critical to the development, function, and survival of β-cells[3]. However, persistent ER stress results in UPR-induced cellular alarm, resulting in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis of β-cells[5]. Emerging evidence suggests the role of sustained ER stress in the development of several metabolic diseases, including T2DM and accompanying complications[6].

DNAJC1: A MOLECULAR REGULATOR IN CELLULAR PROCESSES INCLUDING AUTOPHAGY

The DNAJC1, also known as MCJI is an obesity-associated gene that affects several key cellular processes in the ER, including protein recognition[5,7]. The highly conserved DNAJC1 protein assists in protein maturation; its abnormally high expression levels have been associated with tumor growth and invasiveness in leukemia, melanoma, and glioblastoma[8], stratifying osteosarcoma[9], and hepatocellular carcinoma[10]. Thus, clinically, DNAJC1 holds promise as a prognostic marker and diagnostic biomarker for these cancers. The membrane protein encoded by the DNAJC1 protein can bind to the molecular chaperone membrane-bound Hsp70 protein Grp78 (also known as BiP), which typically localizes to the ER but is regularly translocated to the cell surface[10]. Grp78 is also known to play a role in Sec61 channel closure for induction of protective autophagy[11]. In addition, reduced DNAJC1 levels increased Ca2+ leakage from the ER via the Sec61 complex, causing Ca2+-dependent autophagy[12]. DNAJC1 is a mitochondrial inner membrane protein that is identified as a co-chaperone that inhibits electron transfer chain (ETC) complex I action. The ETC serves as the outlet for FA β-oxidation products; therefore, increased expression of DNAJC1 contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) development via abnormally increased FA accumulation. Thus, reduced expression of DNAJC1 may be a feasible strategy to prevent NAFLD progression[5,7].

MICROENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AFFECTING THE PATHOGENESIS OF T2DM

The pathogenesis of T2DM is categorized by inflammatory-mediated β-cell loss, culminating in progressive insulin deficiency and concurrent insulin resistance. Multiple factors accelerate disease progression, including obesity, aging, ethnicity, and family history. Obesity is the most critical driving factor for T2DM epidemiology, primarily driven by unhealthy diet, lack of physical activity, maternal obesity, and other factors[3]. Microenvironmental factors such as hypoxia, oxidative stress, protein aggregates, and intracellular pathogens also affect the pathogenesis of T2DM. Fibrosis, a pathological process resulting from an abnormality in the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM), restrains the lipid storage of adipocytes and promotes lipotoxicity, which impairs insulin signaling and pancreatic β-cell function. Consequently, lipotoxicity induces mitochondrial dysfunction involving an overproduction of reactive oxygen species, which is detrimental to insulin sensitivity.

Autophagic dysregulation in T2DM is complicated and is subject to various conditions. Excessive intake of nutrients such as lipids, glucose, and amino acids results in the suppression of autophagy via different signaling pathways and contributes to obesogenesis by increasing the accumulation of lipids and proteins, enhancing low-grade systemic inflammation, and exacerbating insulin signaling. SFAs also increase ER stress by activating NF-κB signaling and inflammatory cascades to exacerbate insulin resistance in metabolic organs and immune cells[3,5].

CURRENT THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR T2DM

Various therapeutic agents, including sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones (PPAR-γ agonists), α-glucosidase inhibitors, biguanides (metformin), meglitinides (glinides), amylin analogs, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, are commonly used to treat T2DM; however, their long-term use is often associated with many adverse effects[1]. Current treatment strategies primarily involve monotherapy, resulting in insufficient blood sugar control, significant economic burdens, and potential hepatic and renal side effects. Therefore, the development of novel therapeutic agents that are potent, safe, inexpensive, and effective at improving blood glucose by lowering glycated hemoglobin A1c levels in T2DM patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment is urgently needed. Recent studies have increasingly demonstrated that natural products such as Plantamajoside (PMS) offer promising advantages in managing T2DM patients, irrespective of liver and renal impairment[1,4].

ON-TARGET AND OFF-TARGET ACTIVITIES OF PMS

PMS, a compound belonging to the phenylpropanoid glycoside group, is a major ingredient extracted from Plantago asiatica L. (Plantaginaceae). PMS has been shown to exhibit a wide range of pharmacological action, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-fibrotic, anti-apoptotic, anticancer, and anti-diabetic activities[13]. PMS inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in osteoarthritis via suppression of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways[14]. Additionally, PMS ameliorates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury via mitigation of pulmonary inflammation through suppression of the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways[15].

In a rat model of acute spinal cord injury, PMS inhibits the expression of apoptotic factors caspase-3, caspase-9, PARP, and Bcl-2[15]. PMS further inhibits isoproterenol-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and myocardial hypertrophy in mice and protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by attenuating oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis via modulation of the AKT/Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB signaling pathways[16]. In a previous study on wound healing, carboxymethyl chitosan/PMS hydrogels promoted burn wound healing by accelerating angiogenesis and collagen deposition and reducing the inflammatory response at the wound site[17].

PMS also significantly inhibits neointimal formation in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries via suppression of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through increased expression of the TIMP1 and TIMP2 genes, resulting in control of neointimal hyperplasia in vascular atherosclerosis and restenosis[18]. In mice with neurodegenerative illnesses such as Parkinson's disease, PMS improves LPS-induced behavioral dysfunction, attenuates LPS-induced right midbrain substantia nigra injury, and inhibits LPS-induced activation of the HDAC2/MAPK pathway. PMS also reduces microglia polarization via inhibition of HDAC2[19] and alleviates acute sepsis-induced organ injury and inflammation by inhibiting the TRAF6/NF-κB pathway[20].

Anti-diabetic activity of PMS

PMS has demonstrated anti-diabetic activities via inhibition of high glucose (HG)-induced oxidative stress, lowering the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and alleviating ECM accumulation in rat glomerular mesangial cells and MIN6 insulinoma cells via inactivation of the AKT/NF-κB pathway[21]. Together, these effects suggest the potential of PMS as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Beyond its antioxidant effects, PMS demonstrates strong glycation inhibitory activity, effectively suppressing the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which are implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes and aging-related complications[22].

In the heart, PMS attenuates cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting the AGEs-activated receptor of AGE/autophagy/EndMT pathway[23]. Additionally, PMS exhibits significant cardioprotective effects against isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing HDAC2 activity and down-regulating the AKT/GSK-3β pathway[24]. PMS exerts antifibrotic activity in the liver by inhibiting the activation and survival of hepatic stellate cells via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway[25]. PMS also alleviates liver damage and improves immune dysregulation, abnormal hepatic lipid metabolism, and pathological liver symptoms in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed rats. In rats with NAFLD, PMS modulates immune dysregulation and hepatic lipid metabolism by activating the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway[26]. Thus, PMS exhibits protective effects to the organs commonly affected in T2DM, such as the liver, heart, and kidneys, via regulation of significant pathways.

Metformin and PMS combination

Metformin (1,1-dimethylbiguanide) is a widely used antidiabetic drug with a well-established safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacogenomics profile, having been used clinically for over 50 years in monotherapy or in combination with other drugs. Metformin and PMS are both safe and well-tolerated by the human body. Although PMS at concentrations higher than 10 μg/mL shows anticancer effects in various cancers, including liver cancer, at concentrations less than 10 μg/mL, PMS significantly increases the sensitivity of metformin in liver cancer HepG2 and HuH-7 cells, promotes metformin activity against cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumor xenograft growth[27], and enhances metformin-induced apoptosis and autophagy of liver cancer cells. The combination of PMS and metformin may thus represent a promising strategy for augmenting metformin activity in T2DM[27].

Metformin exerts cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating AMPK-mediated autophagy and inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome[28]. Beyond its antidiabetic action, the PMS-metformin combination may exert potential therapeutic benefits for hepatic diseases, renal disorders, and cardiocerebral vascular diseases.

A recent study by Wang et al[29], published in the World Journal of Diabetes, investigated the therapeutic potential of PMS in T2DM management. The authors provide evidence for the mechanism of action of PMS in T2DM in vitro and in vivo animal models via upregulation of DNAJC1, which prevents ER stress and apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells. However, the authors offer no evaluation for combination therapy using PMS and metformin in the T2DM mouse model in their study.

COMPETITIVE DEBATES: POINTS OF STRENGTH AND WEAKNESS IN THE STUDY OF WANG ET AL

Wang et al[29] demonstrated that PMS protects MIN6 insulinoma cells from HG and palmitic acid (PA)-induced damage. However, PA can affect insulin sensitivity via post-translational modifications, such as palmitoylation of proteins at cysteine residues (e.g., palmitoylation of the GLUT4 and IRAP in adipocytes[30]. While PMS exhibits a wide spectrum of biological activities, including antidiabetic effects, its bioavailability is notably low. PMS is rapidly metabolized by gut microbiota into five active metabolites: Calceolarioside A, dopaol glucoside, hydroxytyrosol, 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl) propionic acid, and caffeic acid. These metabolites affect the metabolism of short-chain FA and amino acid tryptophan metabolism by gut microbiota, suggesting their potential contributions to the antidiabetic activity of PMS[31]. PMS may also improve the proliferation and insulin secretion of pancreatic β cells via upregulation of microRNAs, including miR-136-5p and miR-149-5p[1]. However, these mechanisms remain to be investigated.

Wang et al[29] in their study demonstrated several strengths, integrating in vitro experiments using MIN6 cells with in vivo studies using a type 2 diabetes STZ-induced mouse model. This dual approach strengthens the translational relevance of the study by bridging cellular-level findings with whole-organism validation, providing a robust foundation for preclinical exploration.

Specifically, the use of siRNA-mediated gene silencing to directly silence DNAJC1 represents a significant methodological strength, providing evidence for the critical role of DNAJC1 in the protective action of PMS on pancreatic β-cells. This approach highlights the causal relationship between DNAJC1 expression and the inhibition of ER stress and apoptosis, advancing mechanistic insights into the action of PMS.

Transcriptomic analysis further enhances the study’s value by offering a comprehensive perspective on the molecular changes induced by PMS. Transcriptomic profiling of MIN6 cells treated with PMS reveals differentially expressed genes, pinpointing ER stress and apoptosis pathways as key mechanisms. This supports targeted validations and enriches the molecular understanding of the effects of PMS.

Wang et al[29] employed various robust methodologies to provide reliability to their conclusions, including the use of western blotting to evaluate ER stress markers (e.g., CHOP, ATF6, GRP78), flow cytometry for the detection of apoptosis via Annexin FITC, including Bcl-2, BAX, and Cyt. C, and cell viability assessments using MTT assays. Moreover, the inclusion of control groups, PMS dosage variations, and dose-dependent analyses strengthens the validity of the findings and clarifies the therapeutic potential of PMS.

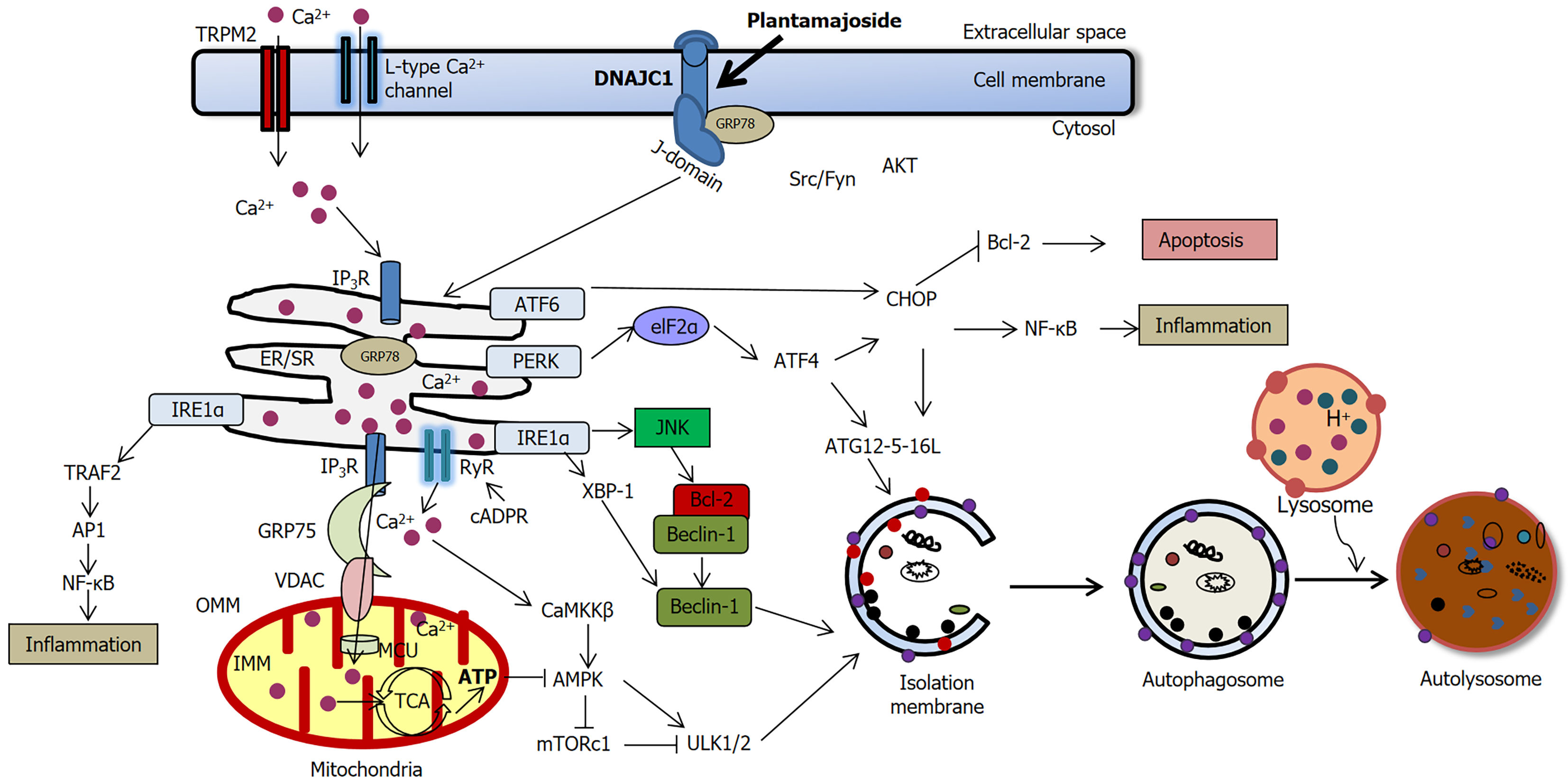

Focusing on ER stress and apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells, the study addresses key pathological mechanisms underlying T2DM, underscoring its potential clinical relevance. Figure 1 demonstrates the effects of PMS on pancreatic β-cells in T2DM based on the study of Wang et al[29] and other studies reporting the pro-autophagic role of PMS[3,5,23,26,27,32-34].

Figure 1 The effects of Plantamajoside on pancreatic β-cells in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Upregulation of DNAJC1 results in the suppression of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress markers such as CHOP and β-cell apoptosis[29]. ERK and NF-κB regulate both pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic effects, depending on the stimulus and the cell type. The ER stress marker CHOP stimulates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by inhibiting the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Bcl-2 inhibition by CHOP releases the autophagy protein Beclin-1 from the Bcl-2-Beclin1 complex, allowing Beclin-1 to initiate autophagy via the formation of isolation (autophagosomal) membrane. Thus, Plantamajoside may inhibit apoptosis and activate autophagy in stressed β-cells as a pro-survival mechanism[3,5,23,26,27,32-34].

Despite its strengths, the study by Wang et al[29] has several limitations. One notable weakness is the limited scope of gene silencing. The study focuses exclusively on DNAJC1 as the target for gene silencing, potentially overlooking other gene regulatory pathways that could contribute to the protective mechanism of PMS. A broader exploration of related genes is necessary for comprehensive insight into related PMS mechanisms of action.

Additionally, the mechanistic insights presented in the study warrant further investigation. While DNAJC1 is identified as a key mediator, the detailed mechanism by which PMS upregulates DNAJC1 remains unclear. The use of advanced techniques, such as cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) or drug affinity responsive targets stability (DARTS) assays[35,36], could help clarify the direct molecular targets of PMS.

Furthermore, the cell line model employed in the study has certain limitations: The use of the in vitro model of HG + PA-induced MIN6 cell damage does not fully capture the complex pathophysiology of T2DM, which includes oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and metabolic disturbances. Key pathways such as AMPK/mTOR signaling and the role of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) also remain unexplored in this study.

Additionally, the absence of conditional knockout models[37], such as the Cre-LoxP system for DNAJC1 in pancreatic β-cells limits the depth of mechanistic in vivo validation in the study, reducing the potential for extrapolation of findings to clinical settings. The transcriptomic analysis presented in the study also lacks transparency, as it does not provide the full list of differentially expressed genes or DNA-level validation through qPCR. The inclusion of these details could enrich secondary analyses and reinforce findings[38].

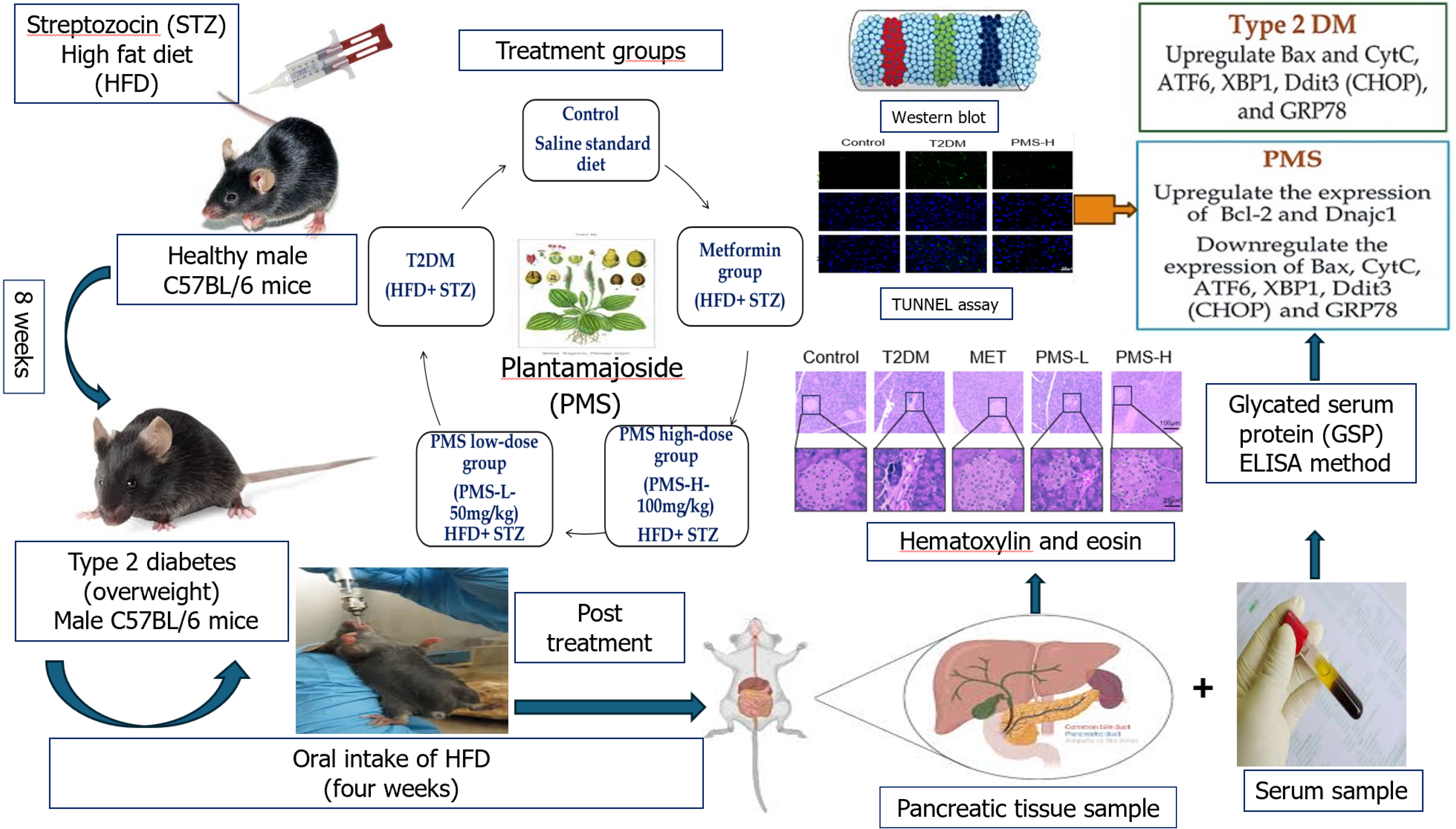

With regard to the in vivo investigation, reliance on a single animal model (C57BL/6 mice treated with STZ and HFD) in the study limits the generalizability of the findings[29] (Figure 2). Including additional models across different genetic backgrounds, age groups, or diabetes phenotypes would provide broader validation and strengthen the translational relevance of the results.

Figure 2 A summary of various molecular biology methods used in the in vivo study by Wang et al[29].

Citation: Wang D, Wang YS, Zhao HM, Lu P, Li M, Li W, Cui HT, Zhang ZY, Lv SQ. Plantamajoside improves type 2 diabetes mellitus pancreatic β-cell damage by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress through Dnajc1 up-regulation. World J Diabetes 2025; 16: 99053 [PMID: 39959264 DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i2.99053] Copyright© The Authors 2025. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc.

In addition, the details and statistical analysis of the TUNEL assay for detecting apoptotic pancreatic β-cells in the study were not adequately described (Figure 2). The use of TUNEL/double labeling using specific antibodies for β-cells would more precisely identify the specific cells undergoing apoptosis. Similarly, the study lacks statistical evaluation of β-cell damage based on histopathological analysis (using H&E staining). Inclusion of a statistical analysis may support and add strength to these findings (Figure 2).

Finally, the authors did not employ transmission electron microscopy for detection of apoptosis, resulting in the absence of detailed insight into ER stress and mitochondrial damage-induced mechanisms of apoptosis, which is highlighted in literature[39,40].

A more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying PMS antidiabetic action can be achieved by expanding investigations into gene silencing to include other genes that are potentially involved in ER stress and apoptosis pathways. The adoption of advanced techniques such as CETSA and DARTS, as well as the use of conditional knockout mouse models to validate the role of DNAJC1 in vivo would allow the direct molecular targets of PMS in β-cells to be identified and offer deeper mechanistic insights into the protective effects of PMS.

Additionally, the use of multiple animal models, including gender- and age-specific cohorts would further enhance the translational potential of the findings in the study. A more detailed presentation of transcriptomic data, and validation at the DNA level using specific primers would improve reproducibility and facilitate secondary analyses. Moreover, the exploration of additional pathways, such as the autophagy-linked AMPK/mTOR pathway and regulation of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α), could uncover additional mechanisms through which PMS exerts its effects to provide a broader and more nuanced understanding of the therapeutic potential of PMS.

CONCLUSION

The study by Wang et al[29] exemplifies the potential of molecular biology methods, particularly gene silencing, to unravel the therapeutic mechanisms of natural compounds such as PMS. However, addressing the study’s limitations and incorporating advanced experimental designs could significantly refine the study’s understanding of the role of PMS in T2DM, paving the way for clinical applications.

T2DM is linked to several cardiorenal-metabolic diseases such as diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetic nephropathy, primarily due to hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. The therapeutic potential of natural products such as PMS highlights the importance of exploring preventive and therapeutic strategies for T2DM treatment. In vivo and in vitro experiments indicate that PMS mitigates pancreatic β-cell injury by upregulating DNAJC1 expression, thereby diminishing ER stress and apoptosis in these cells. The precise mechanisms of action behind PMS regulation of DNAJC1 expression, specifically via the autophagy pathway requires further investigation. Finally, advanced integration techniques such as using gene knockout mice and single-cell sequencing could offer deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms of PMS for T2DM treatment. These approaches would support the establishment of detailed molecular pathways and reinforce the translational potential of PMS in future research. Despite the lack of large-scale clinical studies, the identification of DNAJC1 as a novel target of PMS positions it as a promising therapeutic candidate for the treatment of T2DM.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country of origin: Malaysia

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Balbaa M; Liu L; Zhang YG S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xu ZH