Published online Sep 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.379

Peer-review started: May 11, 2017

First decision: May 23, 2017

Revised: May 24, 2017

Accepted: June 30, 2017

Article in press: July 3, 2017

Published online: September 15, 2017

Processing time: 123 Days and 0.5 Hours

To study tumor response, and tolerability of arterially directed embolic therapy (ADET) with polyethylene glycol embolics loaded with irinotecan for the treatment of colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRC-LM). Secondary objectives were to monitor quality of life, time to progression and survival of patients.

Patients were included in the study if they were affected by CRC-LM, refractory to systemic chemotherapy, treated with ADET using polyethylene glycol embolics, and had liver involvement < 50%. Tumor response, performance status (PS), tumor marker antigens, and quality of life (QoL) were monitored at 1, 3 and 6 mo after ADET. QoL was assessed with the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS).

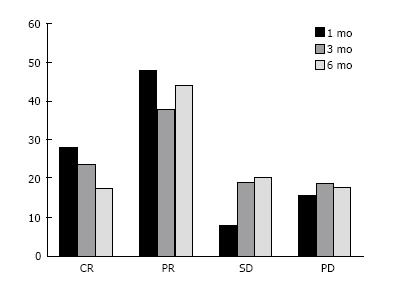

We treated 50 consecutive CRC-LM patients with ADET using polyethylene glycol embolics. Their tumor response one month after ADET was: 28% of complete response (CR), 48% of partial response (PR), 8% stable disease (SD), and 16% of progression. Tumor response 3 mo after ADET was CR 24%, PR 38%, SD 19% and progression disease (PD) 19%. Tumor response 6 mo after ADET was CR 18%, PR 44%, SD 21% and PD 18%. QoL was 90% PPS at each time point. Median time to progression for patients who progressed was 2.5 mo (range 0.8-6). Median follow-up was 14 mo (0.8-25 range). ADETs were performed with no complications. Observed side effects (mild or moderate intensity) were: Pain in 32% of patients, increase of transaminase levels in 20% and fever in 14%, whereas 30% of patients did not complain any adverse event.

The treatment of unresectable CRC-LM with ADET using polyethylene glycol microspheres loaded with irinotecan was effective in tumor response and resulted in mild toxicity, and good QoL.

Core tip: Patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer are in 80% of cases non-indicated for resection. The standard first line treatment of unresectable liver metastases is systemic chemotherapy, however this method results in progression for 70% of patients. The indicated therapy for refractory patients is the chemoembolization. In this study, we monitored tumor response, and adverse events after chemoembolization of colorectal cancer liver metastases with polyethylene glycol embolics loaded with irinotecan. Chemoembolization with these embolics is effective in terms of tumor response, time to progression, survival and quality of life and resulted in mild toxicity.

- Citation: Fiorentini G, Carandina R, Sarti D, Nardella M, Zoras O, Guadagni S, Inchingolo R, Nestola M, Felicioli A, Barnes Navarro D, Munos Gomez F, Aliberti C. Polyethylene glycol microspheres loaded with irinotecan for arterially directed embolic therapy of metastatic liver cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(9): 379-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i9/379.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i9.379

Patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer (CRC-LM) are non indicated for resection in 80% of cases[1]. The standard first line treatment of unresectable CRC-LM is systemic chemotherapy, administering 5-fluorouracil in association with oxaliplatin and/or irinotecan, and biologics. This method results in limited tumor control with progression for 70% of patients[1]. The treatment of patients refractory to chemotherapy is very challenging, since they will hardly have a response to following chemotherapy lines.

A recent review on CRC-LM therapy methods shows that key strategies are local therapies, including loco-regional and ablative methods[2,3]. Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI), arterially directed embolic therapy (ADET), transarterial embolization associated to selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) are among the most applied locoregional therapies. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation (MWA) and cryoablation are the most used ablative techniques[3].

A recent report shows the efficacy of ADET with irinotecan loaded beads also as neoadjuvant therapy, leading to complete resectability (R0), and resulting in tumor response and survival comparable to those of chemotherapy[4].

The advantages of ADET are several, such as reducing drug leakage, liver and systemic toxicity[5]. ADET is widely used for patients with CRC-LM after failure of surgery or systemic chemotherapy, and can be used for both pre- and post-operative downsizing, reducing the time to surgery, and prolonging overall survival[6].

In our last report, we show that ADET with newly introduced polyethylene glycol microspheres loaded with irinotecan are safe and effective for the treatment of primary and secondary liver cancer[7]. In this study we focused on CRC-LM to assess tumor response, and adverse events after ADET with polyethylene glycol embolics loaded with irinotecan. We also monitor quality of life, time to progression and survival of these patients.

We enrolled 50 consecutive eligible patients affected by unresectable CRC-LM that were refractory to systemic chemotherapy and were treated with ADET using polyethylene glycol embolics and irinotecan (LIFIRI®). Inclusion criteria for patient selection were: > 18 years, histological diagnosis of CRC-LM; refractory to systemic chemotherapy, Performance status (PS) 0-2; tumor size evaluable according to RECIST version 1.1[8]; liver involvement < 50%; life expectancy ≥ 3 mo.

Exclusion criteria were: Contraindication to angiographic catheterization; extensive extra-hepatic disease; liver involvement > 50%; pregnancy or breast feeding; other severe clinical impairments.

The interventional radiologist performed a diagnostic angiography to assess tumor arterial perfusion before ADET. Distal catheterization was used in order to avoid extra-hepatic leakage.

ADET was performed infusing 2 mL of LifePearl® (Terumo Europe NV, Leuven, Belgium) that were loaded with irinotecan (100 mg), and diluted in 5 mL of non-ionic contrast solution and 5 mL of distilled water[7]. The diameter of miscrospheres was 100 ± 25 micron. Infusion median time was 12 min at a fixed speed of 1 mL/min. It was possible to perform a second ADET after 30 d, according to physician evaluation of tumor response. Periprocedural and supportive therapy to prevent side effects were administered as in our previous study[9,10].

RECIST criteria version 1.1[11] and European Association for the Study of Liver Disease method[12] were used for tumor response assessment from abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) imaging. Tumor response was monitored at 1, 3 and 6 after ADET.

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE), version 3.0 was applied for adverse events classification and intensity evaluation.

Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) was used for quality of life (QoL) at 1, 3, and 6 mo after ADET[13]. Our hypothesis was that patients would have better physical and social characteristics, and better health perception one month after ADET.

Data analysis of the sample (n = 50) was performed. The median was computed for continuous data, and proportions were expressed in percentage. Significance of continuous variables was assessed with χ2 and Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

The sample included 50 patients affected by CRC-LM that were treated with ADET using polyethylene glycol embolics and irinotecan (LIFIRI®). Twenty-eight (56%) patients were males and 22 (44%) females. Median sample age was 63 years (range 46-86). PS was 0 at baseline in 35 (70%) patients, PS = 1 in 13 (26%) patients and PS = 2 in 2 (4%) patients. Other site of concomitant metastases were: Lung in 2 (4%), lymph nodes in 1 (2%) and lung, omentum and ovary in 1 (2%) patient (Table 1).

| n | % (range) | |

| Male | 28 | 56 |

| Female | 22 | 44 |

| Age (yr), median | 63 | (46-86) |

| Tumor size (mm), median | 35 | (5-130) |

| 1-2 nodules | 15 | 30 |

| 3-5 nodules | 18 | 36 |

| > 5 nodules | 17 | 34 |

| Tumor antigens | ||

| Ca 19.9 (U/mL), median baseline | 14 | (1.9-7628) |

| Ca 19.9 (U/mL), median 1 mo | 10.3 | (1.8-1558) |

| Ca 19.9 (U/mL), median 3 mo | 20 | (5.8-1234) |

| Ca 19.9 (U/mL), median 6 mo | 85 | (2.6-1138) |

| CEA (U/mL), median baseline | 31.1 | (0.7-453) |

| CEA (U/mL), median 1 mo | 35 | (3-370) |

| CEA (U/mL), median 3 mo | 32.5 | (3-1057) |

| CEA (U/mL), median 6 mo | 22.85 | (0.5-735) |

| Previous surgery | ||

| Primary tumor resection | 48 | 96 |

| Metastasectomy | 17 | 34 |

| No surgery | 2 | 4 |

Surgery of primary tumor was done in 48 (96%) and metastasectomy in 17 (34%) patients. Tumor markers levels CEA and Ca 19.9, and tumor size were reported in Table 1. Most of the sample 72% received one ADET, whereas 5 (22%) patients received two ADETs.

One month after ADET we observed 14 (28%) complete response (CR), and 24 (48%) partial response (PR), 4 (8%) stable disease (SD), and 8 (16%) progression disease (PD) (Figure 1). Tumor response 3 mo after ADET was 10 (24%) CR, 16 (38%) PR, 8 (19%) SD and 8 (19%) PD. Tumor response 6 mo after ADET was 6 (18%) CR, 15 (44%) PR, 7 (21%) SD and 6 (18%) PD. Median time to progression for patients who progressed was 2.5 mo (range 0.8-6). Median follow-up was 14 mo (0.8-25 range). Overall survival was (OS) 14 mo (range 1.3-25).

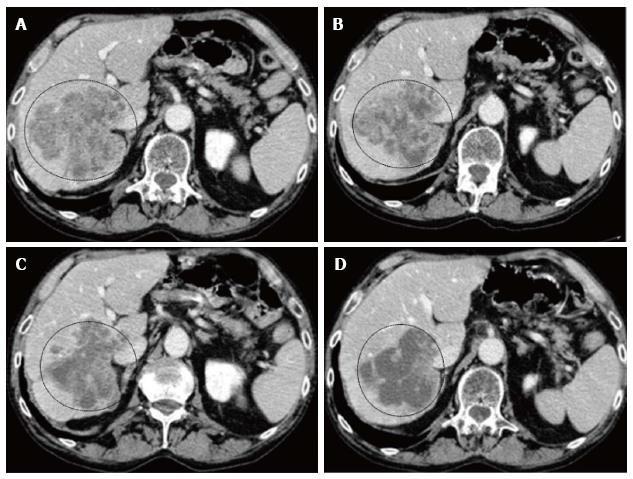

We report the imaging of a particular case that we treated. The imaging showed a voluminous unresectable metastases in the right lobe of one patients at diagnosis (Figure 2). One month after LIFIRI, there was reduction of contrast enhancement and increase of necrotic areas, at 3 mo after LIFIRI, tumor shrinkage and reduction of viable tissue was observed, and at 6 mo after LIFIRI, the metastases appeared almost completely necrotic.

No complications were observed during ADET. Most reported adverse events after ADET were symptoms correlated to the post-embolic syndrome (PES) (Table 2). Observed side effects were of mild (88%) or moderate intensity (12%). They included: Pain in 16 (32%) and fever in 7 (14%) patients. Transaminase rise > 2.5 upper normal level (ULN) was observed in 10 (20%) patient. Adverse effects were all mild (G1) intensity except one case of moderate (G2) Transaminase rise and two cases of pain, and they were all resolved without complications. Thirty four (68%) patients did not complain any adverse event.

| n (%) | |

| Pain | 16 (32) |

| Transaminase rise | 10 (20) |

| Fever | 7 (14) |

| None | 20 (40) |

QoL was 90% PPS at each time point, 3, 6 and 9 mo after ADET, suggesting improvements in physical and social functions and better health perception.

Systemic therapy for unresectable CRC-LM had an OS of 20-27 mo and patients’ deaths were mainly due to disease progression[14]. Locoregional therapies were introduced in order to improve survival, and include different methods: HAI, radioembolization (RE), and ADET[15-18].

These intrahepatic arterial therapies were developed because the liver disease mainly exploits the arterial system as source of blood supply, whereas normal liver relies on portal circulation[19,20]. A review on their efficacy of these locoregional methods showed that HAI, RE, and ADET had similar tumor response in patients affected by unresectable CRLM, and only small differences in overall survival[18]. Other studies reported ADET efficacy also as neo-adjuvant therapy for CRC-LM, obtaining significant surgical down-staging with irinotecan eluting beads[4,21].

Advantages of ADET were based on the application of drug eluting bead that can deliver a high concentrations of toxic chemotherapeutic drug in the liver minimizing the leakage into adjacent tissues, by embolizing the terminal arterial capillaries[22,23]. ADET has been increasingly used in the last decades for CRC.LM, and several improvements of the methodology has been applied. Improvements included the direct beads delivery into the tumor without increasing risks, prolonged exposure to new toxic drug, and the application of new types of beads.

In our last study we reported the use of ADET with PEG embolics for the treatment of primary (HCC and cholangiocarcinoma) and metastatic (CRC, breast and uvea) liver cancer[7,24]. We applied ADET with these new type of PEG microspheres loaded with irinotecan (LIFIRI®) to a larger sample of CRC-LM (50 patients), and we collected data on tumor response, adverse events, QoL, time to progression and survival.

We observed 28% of CR and 24% of PR in patients affected by CRC-LM one month after the LIFIRI®. Tumor response 3 mo after ADET was CR 24%, PR 38%, SD 19% and PD 19%. Tumor response 6 mo showed an increase of PR and a decrease of CR, whereas SD and PD were stable: CR 18%, PR 44%, SD 21% and progression disease (PD) 18%. Median time to progression was 2.5 mo (range 0.8-6). These data were in agreement with results reported by other studies showing response rate in the range of 60%-75%[22-25].

ADETs were performed with no complications. Observed side effects were all of mild (G1) or except one of moderate intensity (G2). Adverse events were: Pain (32%) and hypertransaminemia in 20% of patients and fever in 7%. These symptoms were correlated to post embolic syndrome, as reported in other studies[9,10,25]. Many patients (40%) did not complain any adverse event.

QoL was measured with PPS, and data analysis showed a PPS of 90% at each time point after ADET, suggesting good physical and social functions, and health perception. These data were reported also when measuring QoL after ADET with DC-Beads[9]. This may suggest that comparable results may be attained with PEG microspheres in respect of previous available drug-eluting beads.

Our study has several limitations, such as the small number of patients observed and the short time of follow-up. Our results, however, were very interesting because they were the first to report the feasibility and tolerability of ADET with PEG microspheres for the treatment of unresectable CRC-LM that were refractory to systemic chemotherapy. Future multicenter randomized studies with a larger number patients and longer times of observation are required to confirm these data.

The therapy of unresectable CRC-LM with ADET using polyethylene glycol microspheres loaded with irinotecan was effective in tumor response and resulted in mild toxicity, and good QoL, showing non-inferior results than previous drug eluting beads.

Patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer are in 80% of cases non indicated for resection. The standard first line treatment of unresectable liver metastases is systemic chemotherapy, however this method results in progression for 70% of patients. The indicated therapy for refractory patients is the arterially directed embolic therapy (ADET).

ADET of colorectal cancer liver metastases with polyethylene glycol embolics loaded with irinotecan was effective in tumor response and resulted in mild toxicity, and good quality of life (QoL), showing non-inferior results than previous drug eluting beads.

The use of polyethylene glycol (PEG) microspheres allow a high tumor response maintaning low levels of toxicity, and are an important innovation in the treatment of un-resectable liver metastases from colon carcinoma. These microsphere are more resilient to stress and attrition.

ADET: Delivery of embolics directly inside the tumor-feeding vessels by arterial infusion; PEG is a hydrophilic material that allows a good elasticity, compressibility, and maximizes suspension time.

Overall, this is a very strong prospective study with solid experimental design. The manuscript is well written and the results support the authors’ conclusion. The results are novel and provide promising clue to physicians.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: He SQ, Sun XT S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Adam R, de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Aloia TA, Delvart V, Azoulay D, Bismuth H, Castaing D. Is hepatic resection justified after chemotherapy in patients with colorectal liver metastases and lymph node involvement? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3672-3680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dhir M, Jones HL, Shuai Y, Clifford AK, Perkins S, Steve J, Hogg ME, Choudry MH, Pingpank JF, Holtzman MP. Hepatic Arterial Infusion in Combination with Modern Systemic Chemotherapy is Associated with Improved Survival Compared with Modern Systemic Chemotherapy Alone in Patients with Isolated Unresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gruber-Rouh T, Marko C, Thalhammer A, Nour-Eldin NE, Langenbach M, Beeres M, Naguib NN, Zangos S, Vogl TJ. Current strategies in interventional oncology of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Radiol. 2016;26:20151060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jones RP, Malik HZ, Fenwick SW, Terlizzo M, O’Grady E, Stremitzer S, Gruenberger T, Rees M, Plant G, Figueras J. PARAGON II - A single arm multicentre phase II study of neoadjuvant therapy using irinotecan bead in patients with resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1866-1872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kettenbach J, Stadler A, Katzler IV, Schernthaner R, Blum M, Lammer J, Rand T. Drug-loaded microspheres for the treatment of liver cancer: review of current results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:468-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Massmann A, Rodt T, Marquardt S, Seidel R, Thomas K, Wacker F, Richter GM, Kauczor HU, Bücker A, Pereira PL. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for colorectal liver metastases--current status and critical review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:641-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aliberti C, Carandina R, Sarti D, Mulazzani L, Catalano V, Felicioli A, Coschiera P, Fiorentini G. Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Polyethylene Glycol Drug-eluting Beads for Primary and Metastatic Liver Cancer Therapy. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:3515-3521. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12751] [Cited by in RCA: 13076] [Article Influence: 523.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fiorentini G, Aliberti C, Tilli M, Mulazzani L, Graziano F, Giordani P, Mambrini A, Montagnani F, Alessandroni P, Catalano V. Intra-arterial infusion of irinotecan-loaded drug-eluting beads (DEBIRI) versus intravenous therapy (FOLFIRI) for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: final results of a phase III study. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1387-1395. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Fiorentini G, Aliberti C, Benea G, Montagnani F, Mambrini A, Ballardini PL, Cantore M. TACE of liver metastases from colorectal cancer adopting irinotecan-eluting beads: beneficial effect of palliative intra-arterial lidocaine and post-procedure supportive therapy on the control of side effects. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:2077-2082. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chung WS, Park MS, Shin SJ, Baek SE, Kim YE, Choi JY, Kim MJ. Response evaluation in patients with colorectal liver metastases: RECIST version 1.1 versus modified CT criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:809-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Forner A, Ayuso C, Varela M, Rimola J, Hessheimer AJ, de Lope CR, Reig M, Bianchi L, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Evaluation of tumor response after locoregional therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: are response evaluation criteria in solid tumors reliable? Cancer. 2009;115:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Myers J, Kim A, Flanagan J, Selby D. Palliative performance scale and survival among outpatients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:913-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zarour LR, Anand S, Billingsley KG, Bisson WH, Cercek A, Clarke MF, Coussens LM, Gast CE, Geltzeiler CB, Hansen L. Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis: Evolving Paradigms and Future Directions. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:163-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kingham TP, D’Angelica M, Kemeny NE. Role of intra-arterial hepatic chemotherapy in the treatment of colorectal cancer metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:988-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kemeny NE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Lenz HJ, Warren RS, Naughton MJ, Weeks JC, Sigurdson ER, Herndon JE, Zhang C. Hepatic arterial infusion versus systemic therapy for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a randomized trial of efficacy, quality of life, and molecular markers (CALGB 9481). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1395-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nishiofuku H, Tanaka T, Aramaki T, Boku N, Inaba Y, Sato Y, Matsuoka M, Otsuji T, Arai Y, Kichikawa K. Hepatic arterial infusion of 5-fluorouracil for patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer refractory to standard systemic chemotherapy: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9:305-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zacharias AJ, Jayakrishnan TT, Rajeev R, Rilling WS, Thomas JP, George B, Johnston FM, Gamblin TC, Turaga KK. Comparative Effectiveness of Hepatic Artery Based Therapies for Unresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Breedis C, Young G. The blood supply of neoplasms in the liver. Am J Pathol. 1954;30:969-977. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Liu DM, Salem R, Bui JT, Courtney A, Barakat O, Sergie Z, Atassi B, Barrett K, Gowland P, Oman B. Angiographic considerations in patients undergoing liver-directed therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:911-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bower M, Metzger T, Robbins K, Tomalty D, Válek V, Boudný J, Andrasina T, Tatum C, Martin RC. Surgical downstaging and neo-adjuvant therapy in metastatic colorectal carcinoma with irinotecan drug-eluting beads: a multi-institutional study. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tang Y, Taylor RR, Gonzalez MV, Lewis AL, Stratford PW. Evaluation of irinotecan drug-eluting beads: a new drug-device combination product for the chemoembolization of hepatic metastases. J Control Release. 2006;116:e55-e56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martin RC, Robbins K, Tomalty D, O’Hara R, Bosnjakovic P, Padr R, Rocek M, Slauf F, Scupchenko A, Tatum C. Transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) using irinotecan-loaded beads for the treatment of unresectable metastases to the liver in patients with colorectal cancer: an interim report. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aliberti C, Carandina R, Sarti D, Pizzirani E, Ramondo G, Mulazzani L, Mattioli GM, Fiorentini G. Chemoembolization with Drug-eluting Microspheres Loaded with Doxorubicin for the Treatment of Cholangiocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:1859-1863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aliberti C, Fiorentini G, Muzzio PC, Pomerri F, Tilli M, Dallara S, Benea G. Trans-arterial chemoembolization of metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the liver adopting DC Bead®, drug-eluting bead loaded with irinotecan: results of a phase II clinical study. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:4581-4587. [PubMed] |