Published online Jun 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i6.257

Peer-review started: December 31, 2016

First decision: February 4, 2017

Revised: February 24, 2017

Accepted: May 18, 2017

Article in press: May 19, 2017

Published online: June 15, 2017

Processing time: 170 Days and 19.2 Hours

To evaluate clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of gastric cancer in elderly and non-elderly patients after inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method using propensity score.

We enrolled a total of 448 patients with histologically confirmed primary gastric carcinoma who received gastrectomies. Of these, 115 patients were aged > 80 years old (Group A), and 333 patients were aged < 79 years old (Group B). We compared the surgical outcomes and survival of the two groups after IPTW.

Postoperative complications, especially respiratory complications and hospital deaths, were significantly more common in Group A than in Group B (P < 0.05). Overall survival (OS) was significantly lower in Group A patients than in Group B patients. Among the subset of patients who had pathological Stage I disease, OS was significantly lower in Group A (P < 0.05) than Group B, whereas cause-specific survival was almost equal in the two groups. In multivariate analysis, pathological stage, histology, and extent of lymph node dissection were independent prognostic values for OS.

When the gastrectomy was performed in gastric cancer patients, we should recognized high mortality and comorbidities in that of elderly. More extensive lymph node dissection might improve prognoses of elderly gastric cancer patients.

Core tip: Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) attempts to reduce the bias due to confounding variables in estimates of treatment effects. In the present study, we compared the surgical outcomes and survival of elderly gastric cancer patients with that of general population after IPTW. The overall survival of pStage I gastric cancer patients in elderly was lower survival due to death of other diseases. We found that extent of lymph nodes dissection were independent prognostic factors. When the gastrectomy was performed in gastric cancer patients, we should recognized high mortality and comorbidities in that of elderly. This study was reviewed and approved by Nara Hospital, Kindai University review board on human research.

- Citation: Fujiwara Y, Fukuda S, Tsujie M, Ishikawa H, Kitani K, Inoue K, Yukawa M, Inoue M. Effects of age on survival and morbidity in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(6): 257-262

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i6/257.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i6.257

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy after cancers of the lung, breast, colorectal area and prostate; patients in Eastern Asia account for about half of the world’s incidence[1]. In the past decade, incidence of gastric cancer in elderly patients has increased in Japan because of longer life spans of the general population[2]; decisions regarding gastric cancer surgeries in elderly patients have therefore also increased. Many surgeons are reluctant to have elderly patients undergo gastrectomies because of the considerably higher risk of complications from gastrectomies. There were some retrospective studies compared the outcomes of elderly gastric cancer patients to that of general populations, but the effects of age on morbidity, mortality from gastrectomy and/or prognosis are controversial, as no randomized studies have been conducted to our knowledge[3-18]. Also, no standard definition of “elderly” exists; thresholds vary from 65 to 80 years. Therefore, no standard guidelines for the treatment of elderly gastric cancer patients are available.

Recently, the concept of propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) has garnered some attention. PSM and IPTW attempts to reduce bias due to confounding variables in estimates of treatment effects[19]. In the present study, we first evaluated the clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of gastric cancer treated in our department among patients aged 80 years and older, and compared them with those of patients aged 79 years and younger, after IPTW. We then analyzed these data to find optimal cut-off ages for elderly patients with gastric cancer.

A total of 448 patients with histologically confirmed primary gastric carcinoma had gastrectomies in our department between 2005 and 2013. Of these, 115 patients were aged ≥ 80 years old (Group A), and 333 patients were aged ≤ 79 years old (Group B). All patients were American Society of Anesthesiologists risk less than three and there was no selection bias in each groups. Clinicopathological data for these patients were obtained from hospital records. Characteristics of two groups are shown and compared in Table 1. Postoperative complications were evaluated according to CTCAE Version 3.0; complications of grade ≥ 2 were regarded as significant[20]. Tumor location, clinical or pathological stage, degree of lymph node dissection (D0, D1 or D2), and curability (R0, R1 or R2) were assessed according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 13th, and then 14th editions[21,22]. Surgical mortality, morbidity, and hospital mortality were compared between two groups. Mean follow-up time for all patients was 34.57 mo (range: 0.16-113.13 mo). Recurrences were confirmed by computed tomography, tumor markers, and endoscopic examinations. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to patient death (including surgery-associated death or hospital death), or the date of last available information concerning vital status. Cause-specific survival (CSS) is cancer survival in the absence of other cause of death or death from other cancers. CSS and OS were evaluated after IPTW method. This study was approved by our institute’s committee on human research (Approval No.399): Comprehensive informed consent was obtained from all patients when they admitted our hospital prior to surgery.

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Patients number | 115 | 333 | |

| Sex (Male: female) | 73/42 | 135/198 | |

| Mean age (yr) | 83.44 | 65.87 | < 0.05 |

| Occupied lesion | 0.693 | ||

| U | 24 | 81 | |

| M | 39 | 114 | |

| L | 52 | 138 | |

| Clinical stage (13th edition) | 0.446 | ||

| IA | 40 | 137 | |

| IB | 30 | 65 | |

| II | 20 | 48 | |

| IIIA | 9 | 39 | |

| IIIB | 8 | 26 | |

| IV | 8 | 18 | |

| Lymph nodes metastasis | 0.639 | ||

| Negative | 76 | 212 | |

| Positive | 39 | 121 | |

| Histological type | 0.1224 | ||

| Intestinal | 70 | 175 | |

| Diffuse | 45 | 158 | |

| Operative procedures | 0.074 | ||

| Distal gastrectomy | 68 | 218 | |

| Total gastrectomy | 34 | 95 | |

| Proximal gastrectomy | 5 | 4 | |

| PPG | 3 | 11 | |

| Partial gastrectomy | 5 | 4 | |

| PD | 1 | ||

| Lymph nodes dissection | < 0.05 | ||

| D0 | 18 | 8 | |

| D1 | 60 | 61 | |

| D2 | 36 | 264 | |

| Curability | < 0.05 | ||

| Curative | 97 | 310 | |

| Non-curative | 18 | 23 |

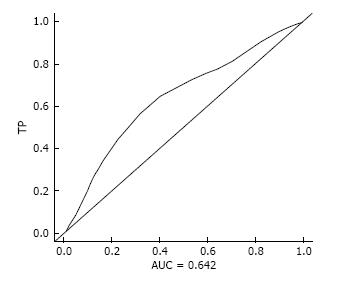

Clinicopathological variables between two groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney test or χ2 test. Survival analysis was carried out using Kaplan-Meier methods, and log-rank test was used to assess survival differences. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The propensity score (PS) was calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model with the two age groups as the dependent variables, and sex, cancer site, cT (14th edition), cN, clinical stage, operative procedures, and histological type (Lauren classification) as independent variables. Inverse probability of treatment weight (IPTW) was then calculated using PS. To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of age in predicting 3-year OS, a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated, and Youden’s index was estimated to determine the optimal cutoff age. Univariate and multivariate analyses used the Cox proportional hazard model for OS after IPTW method. A stepwise method was used to estimate predictive variables for OS in multivariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 14 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, United States), R version 3.1.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan).

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. Degree of lymph node dissection was significantly more extensive in Group B (P < 0.05), and non-curative dissection was more frequency in Group A (P < 0.05). Optimal cutoff age for gastrectomy in terms of OS was 79.2 years old (AUC = 0.642, TP = 0.536, FP = 0.248, Figure 1). Therefore, we set the cut-off age at 80 years old.

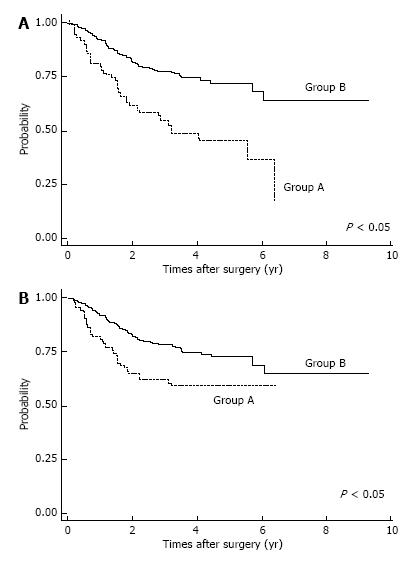

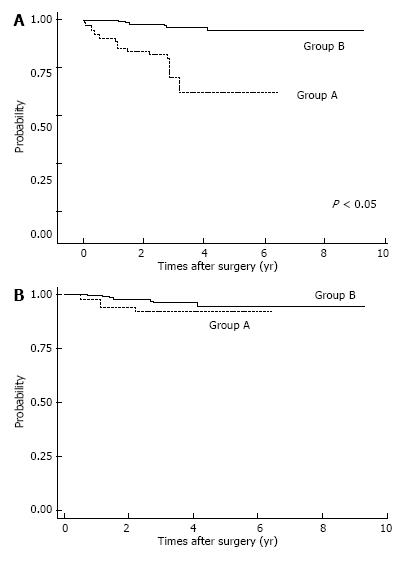

Postoperative complications are shown in Table 2. Respiratory complications and hospital death (including surgery-associated death) were more common in Group A (P < 0.05). After IPTW method, we found OS was significantly lower in Group A patients (P < 0.05; Figure 2A). The OS rates for Group A were 3-year: 46.6%, 5-year: 36.8%; those for Group B were 3-year: 74.8%, 5-year: 68.8%. Also, estimated CSS rates were significantly lower in Group A patients at 3-year, 5-year: 59.7% for Group A; and 3-year: 74.9%, 5-year: 69.1% in Group B (P < 0.05, Figure 2B). Among patients with pStage I disease, OS was significantly lower in Group A (P < 0.05, Figure 3A), whereas CSS was almost equal in both groups (Figure 3B); their estimated 5-year CSS and OS rates were CSS: 92.07%, OS: 62.18% in Group A and CSS, OS: 94.7% in Group B. OS was lower in Group A because of death by other cancers and other diseases, included pneumonia.

| Group A (n = 115) | Group B (n = 333) | P value | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 (4.3) | 8 (2.4) | NS |

| Respiratory complications | 7 (6.0) | 7 (2.1) | < 0.05 |

| Other complications | |||

| Pancreatitis | 3 (2.6) | 7 (2.1) | NS |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 0 (0) | 5 (1.5) | NS |

| Ileus | 1 (0.87) | 1 (0.3) | NS |

| Duodenal stump perforation | 1 (0.87) | 1 (0.3) | NS |

| Hepatic failure | 1 (0.87) | ||

| Cholecystitis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | NS |

| Hospital death | 5 (4.3) | 3 (0.9) | < 0.05 |

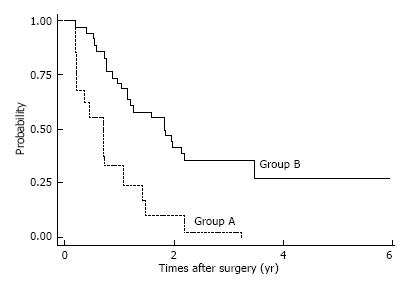

Among patients with pStage II-III disease, CSS and OS rates were almost equal in the two groups. The 5-year estimated CSS/OS rates (same rates) for patients with pStage II disease were 67.5% in Group A and 67.96% in Group B. Estimated 5-year CSS and OS rates for patients with pStage III disease were CSS: 42.4%, OS: 22.16% in Group A and CSS, OS: 23.23% in Group B. However, among patients with pStage IV disease, estimated OS/CSS (same rates) were significantly lower in Group A than in Group B; estimated 5-year CSS/OS were 27, 1% in Group B and 0% in Group A, respectively (Figure 4).

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for OS in Group A is shown in Table 3. We found pStage, radicality, lymph node metastasis and extent of LN dissection significantly affected prognoses (P < 0.05). In multivariate analysis, pStage, histology, and extent of lymph node dissection were independent prognostic values for OS (Table 4).

| Variants | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Sex (male:female) | 0.941 | 0.515-1.720 | 0.845 |

| Tumor location (U:M:L) | 0.967 | 0.779-1.202 | 0.768 |

| Operative procedures (total:others) | 1.005 | 0.813-1.242 | 0.961 |

| Extent of LN dissection (D0:D1:D2) | 0.661 | 0.4233-1.032 | 0.009 |

| pStage (13th edition) (I:II:III:IV) | 2.12 | 1.616-2.782 | 0.001 |

| Radicality (curative:non-curative) | 1.529 | 0.083-0.280 | 0.001 |

| pLN metastasis (negative:positive) | 2.332 | 1.274-4.272 | 0.006 |

| Postoperative complications (negative:positive) | 1.432 | 0.642-3.195 | 0.379 |

| Histology (Lowren) (intestinal:diffuse) | 2.637 | 1.470-4.729 | 0.01 |

| Stepwise method (P < 0.1) | |||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| pStage | 2.014 | 1.516-2.675 | 0.01 |

| Histology (Lauren) | 2.039 | 1.117-3.720 | 0.02 |

| Extent of LN dissection | 0.528 | 0.343-0.813 | 0.004 |

In the present study, we evaluated clinicopathological features and survival of patients aged 80 years and older, compared with patients aged 79 years and younger after IPTW.

The optimal cut-off age for gastrectomies in elderly patients is controversial. The WHO classification defines “elderly” as older than 65 years old, “young-old” as 65-75 years old and “old-old” as older than 75 years[23]. In previously published studies of gastric cancer surgery in older patients, age thresholds ranged from 65 to 80 years old, so “elderly person” was not defined with regard to stomach cancer[4,5,7,8,11-17,24]. In the present study, we therefore used a survival ROC curve in patients with gastric cancer in terms of OS to determine the borderline age for gastrectomies, and concluded the optimal cut-off age is 79.2 years old, regardless of low AUC. Therefore, we divided the gastric cancer patients into two groups: 80 years and older (Group A, elderly group) and 79 years and younger (Group B, general population) in this study.

In general, morbidity and mortality of gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy is controversial; mortality rates for elderly patients with gastric cancer who undergo gastrectomies range from 2% to 8.3% in the published data, which is compatible with our results[3-9,11,15]. Most reports did not find significant differences between the age groups, despite varying definitions of “elderly”. In the present study, surgical mortality was significantly higher in Group A (4.8%) than in Group B (0.9%), possibly because the mortality rate of Group B was less than 1% in our institution. Among postoperative complications, respiratory complications were more frequent in Group A in the present study. Although postoperative respiratory complications in elderly patients have been reported, only two reports noted a high complication rate specifically in elderly patients with gastric cancer[4,6,8,11,15]. Postoperative respiratory complications of elderly gastric cancer patients might be associated with surgical mortality; they therefore warrant more careful postoperative attention.

In analyzing survival of patients with gastric cancer, we matched the two age groups using propensity scores; IPTW is considered to be a reliable statistical method for evaluating propensity scores[25]. Among patients with pStage I disease, OS was significantly lower in Group A, but CSS was not significantly different. Lower OS for elderly pStage I patients was due to surgical mortality, other causes of death, and death from other cancers. Therefore, careful observation after gastrectomy might improve survival of elderly patients with gastric cancer.

In multivariate analysis, we found that extent of lymph node dissection was independent prognostic factors in elderly patients with gastric cancer. Also, postoperative complications, especially respiratory complication and hospital death were more common in elderly group. However, relationships between extent of lymph node dissection and postoperative morbidity, mortality and prognosis in elderly gastric cancer patients are controversial in the literature[3,4,7,11].

Most of these reports showed that more extended lymphadenectomy in elderly patients did not affect postoperative complication rates or prognosis.

Only Eguchi et al[4] reported the extent of lymph node dissection in elderly gastric cancer patients to have influenced postoperative complications. Our findings indicate that more extended lymphadenectomy might improve survival in these patients if postoperative complications could be avoided.

In conclusion, our retrospective study indicated that optimal cut-off ages for elderly patients with gastric cancer was eighty years old, and suggests that even if curative surgery is performed for pStage I disease in elderly gastric cancer patients, careful follow up is needed to stay abreast of other diseases, other cancers as outpatients. Additionally, more extensive lymph node dissection might improve prognosis of elderly patients with gastric cancer if postoperative complications could be minimized. However, postoperative complications lead to hospital death should be noted.

In the past decade, incidence of gastric cancer in elderly patients has increased in Japan. There was no randomized study compare the prognosis, morbidity and mortality of elderly gastric cancer patients and that of younger populations. Propensity score matching (PSM) and inversed probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) attempts to reduce bias due to confounding variables in estimates of treatment effects. They evaluated the clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of gastric cancer treated in our department among patients aged 80 years and older, and compared them with those of patients aged 79 years and younger, after IPTW.

There were some retrospective studies compared the outcomes of elderly gastric cancer patients to that of general populations, but the effects of age on morbidity, mortality from gastrectomy and/or prognosis are controversial, as no randomized studies have been conducted to our knowledge.

PSM and IPTW attempt to reduce bias due to confounding variables in estimates of treatment effects. Quasi randomization is possible when they compared elderly group and younger group, statistically.

The clinical significance of elderly gastric cancer patients received gastrectomy were evaluated and revealed the higher postoperative complications and mortality in elderly patients, and more extensive lymph node dissection might improve prognosis of elderly patients with gastric cancer.

This is interesting to report the effects of age on survival and morbidity in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. The author of this manuscript evaluated the gastric cancer patients received gastrectomy in elderly compared to that in younger population. Notably, this manuscript was compared the results of these patients used propensity score.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Han H, Luyer M, Man-i M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20511] [Article Influence: 2051.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 2. | National Cancer Center, Ganjoho jp. Available from: http://ganjoho.jp/public/cancer/stomach/. |

| 3. | Coniglio A, Tiberio GA, Busti M, Gaverini G, Baiocchi L, Piardi T, Ronconi M, Giulini SM. Surgical treatment for gastric carcinoma in the elderly. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eguchi T, Fujii M, Takayama T. Mortality for gastric cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:132-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hanazaki K, Wakabayashi M, Sodeyama H, Miyazawa M, Yokoyama S, Sode Y, Kawamura N, Ohtsuka M, Miyazaki T. Surgery for gastric cancer in patients older than 80 years of age. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:268-275. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Katai H, Sasako M, Sano T, Maruyama K. The outcome of surgical treatment for gastric carcinoma in the elderly. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:112-115. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kubota H, Kotoh T, Dhar DK, Masunaga R, Tachibana M, Tabara H, Kohno H, Nagasue N. Gastric resection in the aged (& gt; or = 80 years) with gastric carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:254-257. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono HA, Shimada H. Comparison of surgical outcomes of gastric cancer in elderly and middle-aged patients. Am J Surg. 2006;191:216-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Orsenigo E, Tomajer V, Palo SD, Carlucci M, Vignali A, Tamburini A, Staudacher C. Impact of age on postoperative outcomes in 1118 gastric cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:39-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sasada S, Ikeda Y, Saitsu H, Saku M. Characteristics of gastric cancer in patients over 80-years-old. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1931-1934. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Saidi RF, Bell JL, Dudrick PS. Surgical resection for gastric cancer in elderly patients: is there a difference in outcome? J Surg Res. 2004;118:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dittmar Y, Rauchfuss F, Götz M, Scheuerlein H, Jandt K, Settmacher U. Impact of clinical and pathohistological characteristics on the incidence of recurrence and survival in elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:338-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu CW, Lo SS, Shen KH, Hsieh MC, Lui WY, P’eng FK. Surgical mortality, survival, and quality of life after resection for gastric cancer in the elderly. World J Surg. 2000;24:465-472. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yamada H, Shinohara T, Takeshita M, Umesaki T, Fujimori Y, Yamagishi K. Postoperative complications in the oldest old gastric cancer patients. Int J Surg. 2013;11:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takeshita H, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Surgical outcomes of gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2891-2898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim DY, Joo JK, Ryu SY, Park YK, Kim YJ, Kim SK. Clinicopathologic characteristics of gastric carcinoma in elderly patients: a comparison with young patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hayashi T, Yoshikawa T, Aoyama T, Ogata T, Cho H, Tsuburaya A. Severity of complications after gastrectomy in elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:2139-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gretschel S, Estevez-Schwarz L, Hünerbein M, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Gastric cancer surgery in elderly patients. World J Surg. 2006;30:1468-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observation studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41-45. |

| 20. | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v30 (CTCAE). Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf. |

| 21. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma.13th ed (in Japanese). Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara 1999; . |

| 22. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 14th ed (in Japanese). Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara 2010; . |

| 23. | Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/. |

| 24. | Fujiwara S, Noguchi T, Harada K, Noguchi T, Wada S, Moriyama H. How should we treat gastric cancer in the very elderly? Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:620-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Austin PC. The performance of different propensity-score methods for estimating differences in proportions (risk differences or absolute risk reductions) in observational studies. Stat Med. 2010;29:2137-2148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |