Published online Nov 15, 2017. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i11.436

Peer-review started: June 6, 2017

First decision: July 26, 2017

Revised: July 31, 2017

Accepted: September 5, 2017

Article in press: September 6, 2017

Published online: November 15, 2017

Processing time: 168 Days and 11.9 Hours

To evaluate the immunohistochemical (IHC) expression of five biomarkers, commonly involved in epithelial mesenchymal/mesenchymal epithelial transition (EMT/MET), in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

In 80 consecutive GISTs the IHC examinations were performed using the EMT-related antibodies E-cadherin, N-cadherin, SLUG, V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 1 (VSIG1) and CD44.

The positivity rate was 88.75% for SLUG, 83.75% for VSIG1, 36.25% for CD44 and 10% for N-cadherin. No correlation was noted between the examined markers and clinicopathological parameters. Nuclear positivity for SLUG and VSIG1 was observed in all cases with distant metastasis. The extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors (e-GISTs) expressed nuclear positivity for VSIG1 and SLUG, with infrequent positivity for N-cadherin and CD44. The low overall survival was mainly dependent on VSIG1 negativity (P = 0.01) and nuclear positivity for SLUG and/or CD44.

GIST aggressivity may be induced by nuclear up-regulation of SLUG and loss or cytoplasm-to-nuclear translocation of VSIG1. SLUG and VSIG1 may act as activated nuclear transcription factors. The CD44, but not N-cadherin, might also have an independent prognostic value in these tumors. The role of the EMT/MET-related transcription factors in the evolution of GISTs, should be revisited with a larger dataset. This is the first study exploring the IHC pattern of VSIG1 in GISTs.

Core tip: In this paper we proved for the first time in the current literature the possible role of V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 1 (VSIG1) in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) in correlation with the expression of the other markers involved in the epithelial mesenchymal/mesenchymal epithelial transition. Based on the obtained results, we hypothesized that the GIST aggressivity may be induced by nuclear upregulation of SLUG and the loss or cytoplasm-to-nuclear translocation of VSIG1.

- Citation: Kövecsi A, Gurzu S, Szentirmay Z, Kovacs Z, Bara TJ, Jung I. Paradoxical expression pattern of the epithelial mesenchymal transition-related biomarkers CD44, SLUG, N-cadherin and VSIG1/Glycoprotein A34 in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9(11): 436-443

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v9/i11/436.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v9.i11.436

Despite the existence of several molecular pathways described as being involved in the genesis and evolution of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), the invasive and metastatic behavior of these tumors is not completely understood. The aim of this immunohistochemistry (IHC) study was to evaluate the possible role of five of the biomarkers commonly involved in the epithelial mesenchymal transition/mesenchymal epithelial transition (EMT/MET) and also in maintaining the stem cell capacity of tumor cells, in the GIST histogenesis. The inspiration for this examination comes from the findings of some recent studies that proved a negative prognostic role of the EMT/MET-related markers in malignant tumors including GISTs[1-4].

In carcinomas, the EMT is defined as the loss of the expression of the transmembrane protein E-cadherin and gain in the positivity of tumor cells for mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin. Another EMT-related biomarker is known as SLUG (SNAIL2), which is a member of the SNAIL family. SLUG is a zinc-finger nuclear transcription protein that can suppress the E-cadherin expression of epithelial cells and favor carcinoma progression[1,2]. There is little known about the clinical significance of E-cadherin, N-cadherin or SLUG in GISTs[3,4]. The first report concerning the clinical significance of SLUG expression in GIST was published in 2017[3]. This study is the second.

CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that plays role in cell-cell adhesion, migration and cell differentiation; during pathological processes, it is involved in tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis[5,6]. CD44 expression is correlated with the phenotype of cancer stem cells but its role in GIST is unclear[7].

V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 1 (VSIG1) or membrane glycoprotein A34, is a member of the junctional adhesion molecules family expressed in normal gastric mucosa and tumors of the upper, but not lower, gastrointestinal tract. Testicular germ cells and ovarian cancers can also display VSIG1 positivity[2,8,9]. The clinical significance and the function of VSIG1 expression in GISTs or other mesenchymal tumors has not yet been explored in the studies published to date.

In the present study we retrospectively evaluated the parraffin-embedded specimens provided from 80 consecutive cases of GISTs diagnosed in our department from 2003 to 2015 in our clinic. The Ethical Committee approval was obtained from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tirgu-Mures, Romania, and the research was performed according to the Helsinki criteria.

The diagnosis of GISTs was performed according to the modified National Institute of Health consensus classification[10]. The IHC diagnosis was based on the the c-KIT/DOG-1/PKCθ panel[11]. The aggressivity was assessed based on the mitotic count associated with the Ki67 index[10].

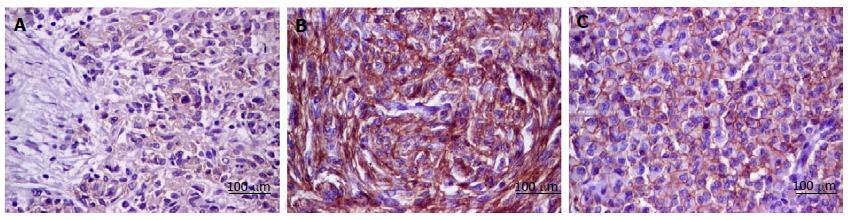

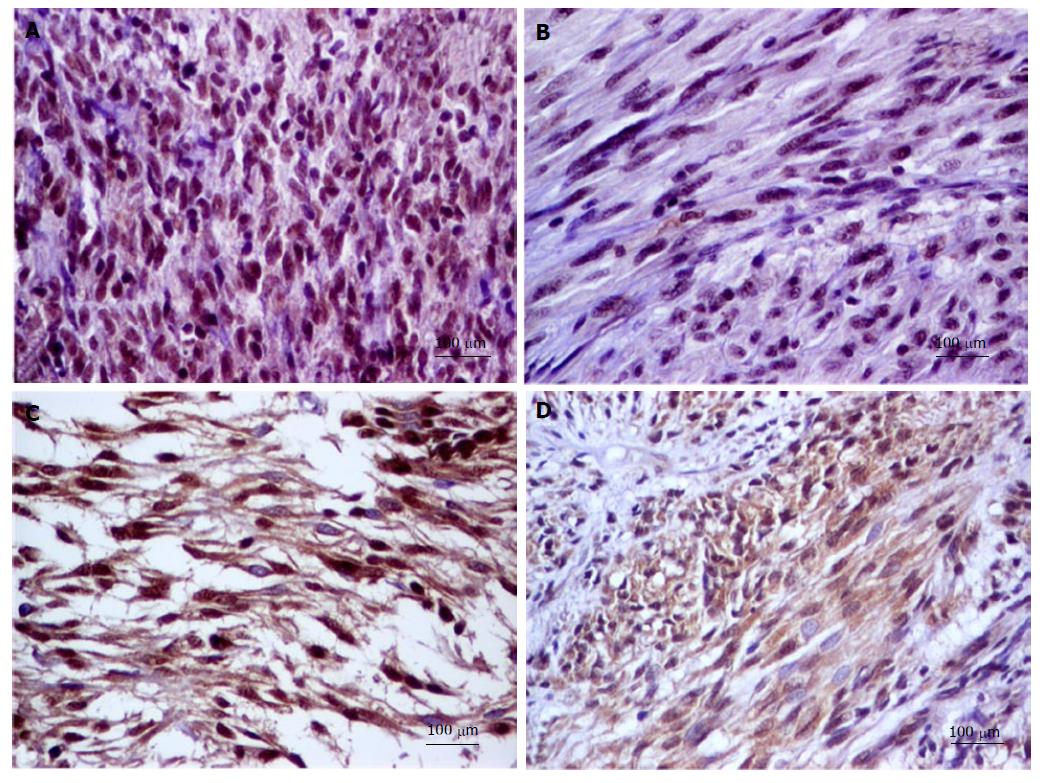

Tissue microarray (TMA) blocks were constructed For this study. From each case, three representative areas of each GIST tissue (3 mm diameter core) were used. The following IHC markers have been assessed: E-cadherin, N-cadherin, SLUG, VSIG1 and CD44 (Table 1). For each antibody, a cut-off value of 5% was used. The E-cadherin and N-cadherin were quantified in the cell cytoplasm. For CD44, the cytoplasmic and/or membrane positivity was taken into account (Figure 1). Regarding SLUG and VSIG1, the cases were considered positive based on the nuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining (Figure 2). Two pathologists independently performed the IHC assessment.

| Antibody (company) | Clone | Dilution |

| C-KIT (Dako) | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:500 |

| DOG1 (Novocastra) | NCL-L-DOG1 | 1:50 |

| PKCθ (ABCAM) | Polyclonal | 1:200 |

| SLUG (Santa Cruz Biotech) | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:100 |

| E-cadherin (Dako) | Monoclonal mouse NCH-38 | 1:50 |

| N-cadherin (Dako) | Monoclonal mouse 6G11 | 1:100 |

| Ki67 (LabVision) | SP6 | 1:200 |

| CD44 (Dako) | Monoclonal mouse DF1485 | 1:50 |

| VSIG1 (SIGMA) | Rabbit polyclonal HPA036311 | 1:200 |

Statistical analysis was done with the GraphPad InStat 3 software and two-sided tests with a P-value < 0.05 and a 95%CI were considered as statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier curves and long-rank test were used to evaluate the independent prognostic value of the examined biomarkers. The median follow-up was 74 ± 44.87 mo (range: 9-163 mo) and the overall survival (OS) was considered to be the time (in months) from operation to death or last follow-up.

Overall, 80 patients were included in the study, 45 women and 35 men, with a median age of 61.58 ±11.84 years (range from 19 to 80 years). The most common location of GISTs was the stomach (n = 35), followed by the small intestine (n = 25), colorectum (n = 6) and extra-gastrointestinal area (n = 14). The median tumor size was of 6.47 ± 1.34 cm (range: 0.4-21 cm). The spindle cell morphology predominated (n = 64), followed by the epithelioid (n = 2) and mixed architecture (n = 14). There was no lymph node metastases observed in the examined cases. Distant metastases (n = 11) were localized in peritoneum (n = 6) and liver (n = 5) (Table 2).

| n | SLUG | CD44 | N-Cadherin | VSIG1 | |||||||||||||

| - | + | OR (95%CI) | P vaule | - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | - | + | OR, (95%CI) | P | - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 35 | 2 | 33 | 0.32 (0.06-1.69) | 0.28 | 22 | 13 | 0.93 (0.37-2.33) | 0.88 | 33 | 2 | 2.53 (0.47-13.4) | 0.45 | 5 | 30 | 0.77 (0.22-2.60) | 0.76 |

| Female | 45 | 7 | 38 | 29 | 16 | 39 | 6 | 8 | 37 | ||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤ 45 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0.39 (0.02-7.38) | 0.58 | 6 | 2 | 1.8 (0.33-9.56) | 0.7 | 7 | 1 | 0.75 (0.08-7.05) | 0.58 | 0 | 8 | 0.25 (0.01-4.77) | 0.34 |

| > 45 | 72 | 9 | 63 | 45 | 27 | 65 | 7 | 13 | 59 | ||||||||

| Tumor size | |||||||||||||||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 45 | 6 | 39 | 1.64 (0.38-7.08) | 0.72 | 29 | 16 | 1.07 (0.42-2.68) | 1 | 40 | 5 | 0.75 (0.16-3.37) | 0.95 | 9 | 36 | 1.93 (0.54-6.91) | 0.37 |

| < 5 cm | 35 | 3 | 32 | 22 | 13 | 32 | 3 | 4 | 31 | ||||||||

| Mitotic rate (50HPF) | |||||||||||||||||

| High (≥ 5) | 29 | 1 | 28 | 0.19 (0.02-1.62) | 0.14 | 18 | 11 | 0.89 (0.34-2.29) | 0.81 | 24 | 5 | 0.30 (0.06-1.36) | 0.13 | 5 | 24 | 1.11 (0.32-3.80) | 1 |

| Low (< 5) | 51 | 8 | 43 | 33 | 18 | 48 | 3 | 8 | 43 | ||||||||

| Tumor location | |||||||||||||||||

| Stomach | 35 | 4 | 31 | NA | 0.47 | 26 | 9 | NA | 0.93 | 32 | 3 | NA | 0.26 | 8 | 27 | NA | 0.21 |

| Small intestine | 25 | 2 | 23 | 10 | 15 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 23 | ||||||||

| 2 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Colorectum | 6 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||

| E-GIST | 14 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 13 | ||||||||

| Histological pattern | |||||||||||||||||

| Spindle cell type | 64 | 7 | 57 | NA | 0.82 | 40 | 24 | NA | 0.75 | 58 | 6 | NA | 0.62 | 11 | 53 | NA | 0.72 |

| Epithelioid cell type | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||

| Mixed type | 14 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 12 | ||||||||

| Risk group | |||||||||||||||||

| Very low | 10 | 2 | 8 | NA | 0.59 | 5 | 5 | NA | 0.19 | 10 | 0 | NA | 0.5 | 1 | 9 | NA | 0.77 |

| Low | 21 | 3 | 18 | 14 | 7 | 19 | 2 | 3 | 18 | ||||||||

| Intermediate | 16 | 2 | 14 | 13 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 14 | ||||||||

| High | 33 | 2 | 31 | 19 | 14 | 28 | 5 | 7 | 26 | ||||||||

| Local invasion | |||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 14 | 1 | 13 | 0.55 (0.06-4.85) | 0.96 | 6 | 8 | 0.35 (0.10-1.13) | 0.12 | 11 | 3 | 0.30 (0.06-1.44) | 0.14 | 1 | 13 | 0.34 (0.04-2.90) | 0.44 |

| Negative | 66 | 8 | 58 | 45 | 21 | 61 | 5 | 12 | 54 | ||||||||

| Distant metastasis | |||||||||||||||||

| Present | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0.27 (0.01-5.09) | 0.38 | 7 | 4 | 0.99 (0.26-3.73) | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0.20 (0.04-1.04) | 0.07 | 0 | 11 | 0.18 (0.01-3.28) | 0.19 |

| Absent | 69 | 9 | 60 | 44 | 25 | 64 | 5 | 13 | 56 | ||||||||

| Necrosis | |||||||||||||||||

| Present | 32 | 1 | 31 | 0.16 (0.09-1.36) | 0.07 | 18 | 14 | 0.58 (0.23-1.47) | 0.23 | 27 | 5 | 0.36 (0.07-1.62) | 0.25 | 3 | 29 | 0.39 (0.09-1.55) | 0.22 |

| Absent | 48 | 8 | 40 | 33 | 15 | 45 | 3 | 10 | 38 | ||||||||

E-cadherin positivity was not noted in the examined cases. Most of the cases (n = 71; 88.75%) showed SLUG positivity and VSIG1 positivity was seen in 67of the 80 cases (83.75%). CD44 and N-cadherin showed positivity in 29 out of 80 (36.25%) and 8 out of 80 cases (10%) respectively.

Not one of the four positive markers (SLUG, CD44, N-cadherin and VSIG1) was statistically correlated with the clinicopathological factors, which included gender, age, tumor size, mitotic rate, tumor location, histological type, intratumoral necrosis, risk degree, Ki67 proliferation index, local invasion, presence or absence of distant metastasis. Most of the extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors (e-GISTs) displayed SLUG and VSIG1 expression without N-cadherin and CD44 positivity (Table 2).

All of the cases with distant metastasis showed the immunophenotype SLUG nuclear positivity/VSIG1 nuclear positivity/N-cadherin±/CD44±. All of the 13 cases, which were negative for VSIG1, displayed nuclear SLUG positivity and were negative for N-caherin. They were included in the cases with a high mitotic rate, high Ki67 index and the high-risk group.

The nine SLUG negative cases that displayed positivity for VSIG1 (predominantly in the cytoplasm) but not for N-cadherin, did not presented necrosis and were included in the cases with a low mitotic rate, Ki67 negative and low-risk group.

All of the six c-KIT negative cases expressed SLUG positivity and were negative for N-cadherin. These cases were positive or negative for CD44 or VSIG1. The expression of SLUG was not correlated with N-Cadherin expression (P = 0.58). A reverse correlation was seen between PKCθ and N-cadherin (P = 0.029) and also between N-cadherin and VSIG1 (P = 0.021). The VSIG1 expression was directly correlated with the PKCθ pattern (P = 0.012) (Table 3).

| n | SLUG | CD44 | N-Cadherin | VSIG1 | |||||||||||||

| - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | - | + | OR (95%CI) | P | ||

| Ki67 index | |||||||||||||||||

| Low | 60 | 9 | 51 | 7.56 (0.42-136.02) | 0.16 | 39 | 21 | 1.23 (0.43-3.50) | 0.68 | 55 | 5 | 1.94 (0.42-8.97) | 0.4 | 9 | 51 | 0.70 (0.19-2.60) | 0.6 |

| High | 20 | 0 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 16 | ||||||||

| C-KIT | |||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 74 | 9 | 65 | 1.88 (0.09-36.23) | 0.67 | 47 | 27 | 0.87 (0.14-5.06) | 0.87 | 66 | 8 | 0.60 (0.03-11.65) | 0.73 | 11 | 63 | 0.34 (0.05-2.14) | 0.25 |

| Negative | 6 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||

| DOG-1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 61 | 7 | 54 | 1.10 (0.20-5.81) | 0.11 | 37 | 24 | 0.55 (0.17-1.72) | 0.3 | 54 | 7 | 0.42 (0.04-3.72) | 0.44 | 6 | 55 | 0.18 (0.05-0.65) | 0.01 |

| Negative | 19 | 2 | 17 | 14 | 5 | 18 | 1 | 7 | 12 | ||||||||

| C-theta | |||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 72 | 7 | 65 | 0.321 (0.05-1.91) | 0.21 | 45 | 27 | 0.55 (0.10-2.95) | 0.49 | 67 | 5 | 8.04 (1.47-43.81) | 0.02 | 9 | 63 | 0.14 (0.03-0.67) | 0.02 |

| Negative | 8 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

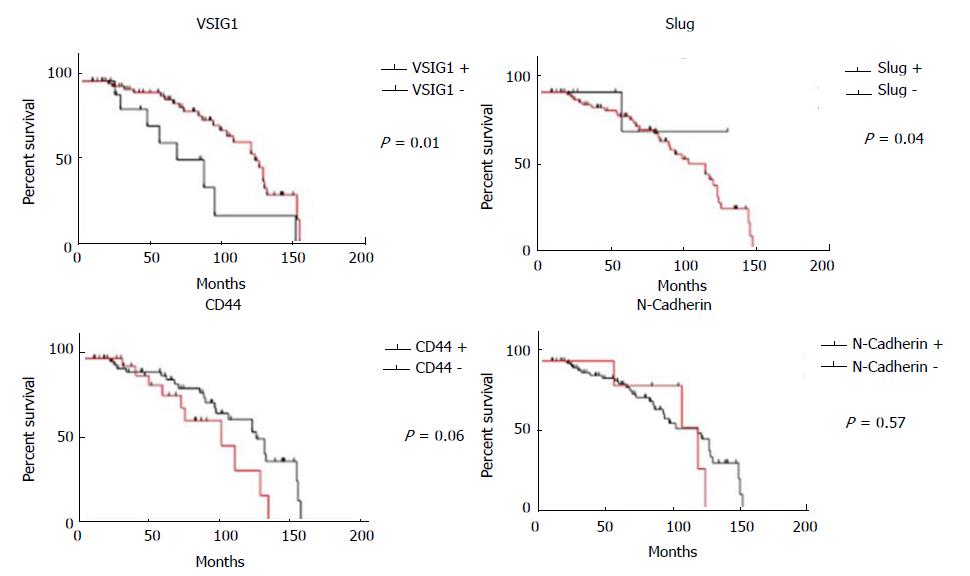

The patients with VSIG1-negative GISTs showed a shorter OS than those with tumors that display VSIG1 positivity (P = 0.01). A univariate Cox regression analysis showed that OS also decreased with CD44 positivity (P = 0.06) and slightly decreased in patients with SLUG or N-cadherin positive GISTs (Figure 3). The VSIG1 expression was the most significant independent prognostic factor.

Based on the above-mentioned aspects, we presume that the loss of VSIG1 is an independent predictor of low OS whereas nuclear positivity for VSIG1 might indicate risk for distant metastasis. The cytoplasmic expression of a GIST is not an indicator of high risk. SLUG positivity indicates an increased risk of metastatic behavior whereas the loss of SLUG positivity is associated with longer OS. Double nuclear positivity for SLUG and VSIG1 indicates aggressive behavior especially for e-GISTs. The GISTs might be classified as tumors with high (SLUG nuclear positivity/VSIG1 negative or nuclear positivity/N-cadherin±/CD44±) or low risk for MET-induced aggressivity (SLUG negative/VSIG1 negative or cytoplasmic positivity/N-cadherin±/CD44±).

The EMT/MET-related biomarkers examined in the present study may have induced aggressivity as result of their role as nuclear transcription factors but CD44. It is important to note that CD44 is also known as a stemness-related biomarker.

About 20%-50% of GISTs can display SLUG expression[3,12-15]. Due to the cut-off value of 5% used here, compared to the 20% used in other studies[3], the positivity rate was found to be higher (88.75%) in our study. Although a possible link between the KIT signaling pathway and the SLUG transcription factor has been proven in experimental studies, it was not proven in our material[3]. SLUG is also proposed to have stemness properties[3] but we did not find it to correlate with CD44. In GISTs, SLUG positivity is considered to be an indicator of a high cell proliferation rate but not for cancer progression[3,12,13] especially in e-GISTs[12-14].

In line with the literature, we confirm the role of SLUG in GISTs aggressivity, especially for e-GISTs. SLUG acts as a nuclear transcription factor, being more frequently expressed by large GISTs with pleomorphic nuclei and high mitotic index[3], and as an indicator of risk for systemic metastases and/or local invasion[3,15].

In the present material, double nuclear positivity for SLUG and VSIG1 has been identified in the metastatic cases and the loss of VSIG1 is associated with a lower OS. Although no data regarding the role of VSIG1 in GIST have been published, its nuclear positivity indicates its possible role as a nuclear transcription factor. In normal gastric epithelium, VSIG1 plays the role of the junctional adhesion molecule that can be lost in carcinomas, as an indicator for a worse clinical outcome[8,9]. In mesenchymal tumors such as GISTs, its loss may indicate a lower survival rate whereas membrane/cytoplasm to nuclear transcription may stimulate tumor cells proliferation and their migration in the blood vessels. As VSIG1 is considered to be a novel target for antibody-based cancer immunotherapy[8], this therapy may benefit patients with VSIG1-positive metastatic GISTs. We found a direct correlation between VSIG1 and the expression of PKCθ and a reverse correlation with N-cadherin expression.

The potential role of N-cadherin in increasing the metastatic potential of GISTs was previously proposed[16] but not confirmed[4].

The cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin and AE1/AE3 keratin might be expressed by one third of GISTs[12,13] as an indicator of low invasion properties and low risk for recurrence[17,18]. In leiomyosarcomas the increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased SLUG expression was associated with decreased cell proliferation, invasion, and migration[19]. In this study, lower levels of aggressive behavior were shown by SLUG negative GISTs.

The CD44 stemness marker was expressed in one quarter of the cases but its positivity can be shown by more than 70% of the GISTs[20,21]. The role of CD44 in tumor progression and metastatic capacity of GISTs has been analyzed in a few studies, however the results are controversial. CD44 positivity might be an indicator of better prognosis[20]. The high-risk group GISTs displayed a significant loss of CD44 expression[21]. Being universally expressed in GISTs, CD44 and CD133 may represent a linkage rather than cancer stem cell markers[22,23]. We did not prove a statistical correlation between CD44 and SLUG. A slightly lower OS was proven for CD44 positive cases compared with CD44 negative ones.

In conclusion, we hypothesized that the EMT/MET of GISTs involves the upregulation of the nuclear transcription factors SLUG and VSIG1. The main shortfall of this paper is the small number of examined cases. The role of the adhesion molecule N-cadherin and stemness factor CD44 in GISTs should be further explored in studies which include a higher number of GISTs. The possible predictive role of VSIG1 expression for immunotherapy and the prognostic significance of its subcellular localization also deserve further exploration.

There are no data in literature regarding the role of V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 1 (VSIG1) in the gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) aggressivity even about its interaction with other biomarkers involved in the epithelial mesenchymal transition/mesenchymal epithelial transition. This is the first immunohistochemistry study exploring the VSIG-related aggressivity of GISTs.

The subcellular location of the mesenchymal epithelial transition-related biomarkers might influence the GIST evolution.

In this paper, the authors hypothesized for the first time in the current literature that the GIST aggressivity may be induced by upregulation of the nuclear transcription factor SLUG and the loss or cytoplasm-to-nuclear translocation of VSIG1.

The possible predictive role of VSIG1 expression for immunotherapy and the prognostic significance of its subcellular localization also deserve further exploration.

Epithelial mesenchymal transition represents loss of the epithelial phenotype with reverse gain of a mesenchymal immunoprofile. Mesenchymal epithelial transition is the reverse phenomenon. These processes are mediated through several signalling pathways that are incompletely understood in GISTs.

This paper reported possible role of VSIG1 in GISTs for the first time, which is related with expression of the other markers involved in the epithelial mesenchymal/mesenchymal epithelial transition.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ferreira Caboclo JL, Lin JM, Wani IA JL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhao LM

| 1. | Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6575] [Cited by in RCA: 7868] [Article Influence: 491.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gurzu S, Turdean S, Kovecsi A, Contac AO, Jung I. Epithelial-mesenchymal, mesenchymal-epithelial, and endothelial-mesenchymal transitions in malignant tumors: An update. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:393-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pulkka OP, Nilsson B, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Reichardt P, Eriksson M, Hall KS, Wardelmann E, Vehtari A, Joensuu H, Sihto H. SLUG transcription factor: a pro-survival and prognostic factor in gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:1195-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ding J, Zhang Z, Pan Y, Liao G, Zeng L, Chen S. Expression and significance of twist, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:2318-2324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marhaba R, Zöller M. CD44 in cancer progression: adhesion, migration and growth regulation. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:211-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sneath RJ, Mangham DC. The normal structure and function of CD44 and its role in neoplasia. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:191-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu H, Tian Y, Yuan X, Wu H, Liu Q, Pestell RG, Wu K. The role of CD44 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer development. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3783-3792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scanlan MJ, Ritter G, Yin BW, Williams C Jr, Cohen LS, Coplan KA, Fortunato SR, Frosina D, Lee SY, Murray AE, Chua R, Filonenko VV, Sato E, Old LJ, Jungbluth AA. Glycoprotein A34, a novel target for antibody-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immun. 2006;6:2. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chen Y, Pan K, Li S, Xia J, Wang W, Chen J, Zhao J, Lü L, Wang D, Pan Q. Decreased expression of V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 1 (VSIG1) is associated with poor prognosis in primary gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kovecsi A, Jung I, Szentirmay Z, Bara T, Bara T Jr. Popa D, Gurzu S. PKCθ utility in diagnosing c-KIT/DOG-1 double negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncotarget. 2017;8:55950-55957. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu S, Liao G, Ding J, Ye K, Zhang Y, Zeng L, Chen S. Dysregulated expression of Snail and E-cadherin correlates with gastrointestinal stromal tumor metastasis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu S, Cui J, Liao G, Zhang Y, Ye K, Lu T, Qi J, Wan G. MiR-137 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:9131-9138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Reichardt A, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Ramadori G, Hohenberger P, Al-Batran SE, Schlemmer M. Adjuvant Imatinib for High-Risk GI Stromal Tumor: Analysis of a Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ding J, Liao GQ, Zhang ZM, Pan Y, Li DM, Chen HJ, Wang SY, Li Y, Wei N. [Expression and significance of Slug, E-cadherin and N-cadherin in gastrointestinal stromal tumors]. Zhonghua YiXue Za Zhi. 2012;92:264-268. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2783] [Cited by in RCA: 2975] [Article Influence: 141.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Angst BD, Marcozzi C, Magee AI. The cadherin superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:625-626. [PubMed] |

| 18. | House MG, Guo M, Efron DT, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Syphard JE, Hooker CM, Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Herman JG. Tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation as a predictor of gastric stromal tumor behavior. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1004-1014; discussion 1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang J, Eddy JA, Pan Y, Hategan A, Tabus I, Wang Y, Cogdell D, Price ND, Pollock RE, Lazar AJ. Integrated proteomics and genomics analysis reveals a novel mesenchymal to epithelial reverting transition in leiomyosarcoma through regulation of slug. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2405-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Montgomery E, Abraham SC, Fisher C, Deasel MR, Amr SS, Sheikh SS, House M, Lilliemoe K, Choti M, Brock M. CD44 loss in gastric stromal tumors as a prognostic marker. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:168-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hsu KH, Tsai HW, Shan YS, Lin PW. Significance of CD44 expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors in relation to disease progression and survival. World J Surg. 2007;31:1438-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen J, Guo T, Zhang L, Qin LX, Singer S, Maki RG, Taguchi T, Dematteo R, Besmer P, Antonescu CR. CD133 and CD44 are universally overexpressed in GIST and do not represent cancer stem cell markers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liang YM, Li XH, Li WM, Lu YY. Prognostic significance of PTEN, Ki-67 and CD44s expression patterns in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1664-1671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |