Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.97644

Revised: December 9, 2024

Accepted: January 15, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 294 Days and 2.5 Hours

Esophageal cancer (ESCA) poses a significant challenge in oncology because of the limited treatment options and poor prognosis. Therefore, enhancing the therapeutic effects of radiotherapy for ESCA and identifying relevant therapeutic targets are crucial for improving both the survival rate and quality of life of patients.

To define the role of the transcription factor Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) in ESCA, particularly its regulation of radiosensitivity.

A comprehensive analysis of TCGA data assessed SNAI1 expression in ESCA. Survival curves correlated SNAI1 levels with radiotherapy outcomes. Colony formation assays, flow cytometry, and a xenograft model were used to evaluate tumor radiosensitivity and apoptosis. Western blot validated protein expression, while Chromatin im

SNAI1 expression in ESCA cell lines and clinical specimens emphasizes its central role in this disease. Elevated SNAI1 expression is correlated with unfavorable outcomes in radiotherapy. Downregulation of SNAI1 enhances the sensitivity of ESCA cells to ionizing radiation (IR), resulting in remarkable tumor regression upon IR treatment in vivo. This study underscores the direct involvement of SNAI1 in the regulation of EMT, particularly under IR-induced conditions. Furthermore, inhibiting deacetylation effectively suppresses EMT, suggesting a potential avenue to enhance the response to radiotherapy in ESCA.

This study highlights SNAI1's role in ESCA radiosensitivity, offering prognostic insights and therapeutic strategies to enhance radiotherapy by targeting SNAI1 and modulating EMT processes.

Core Tip: Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) significantly affects both radiosensitivity and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in esophageal cancer (ESCA), validated by a combination of bioinformatics, clinical data, and experimental studies. Its pivotal role in tumor progression and patient survival suggests that targeting SNAI1 may offer novel strategies to enhance the effectiveness of radiotherapy in ESCA treatment.

- Citation: Lv XL, Peng QL, Wang XP, Fu ZC, Cao JP, Wang J, Wang LL, Jiao Y. Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 radiosensitizes esophageal cancer via epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling: From bioinformatics to integrated study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 97644

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/97644.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.97644

Esophageal cancer (ESCA) remains one of the most lethal malignancies worldwide, ranking as the eighth most common cancer in terms of incidence[1]. Notably, China has one of the highest incidences of ESCA, emphasizing its significant public health burden in the region[2]. The standard therapeutic approaches for ESCA include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, and various combination therapies, each tailored to the specific tumor stage and characteristics [3-8]. Despite these advances, the effectiveness of radiotherapy when used as a standalone treatment is limited, with reported 5-year survival rates ranging between 15% and 30%[9,10]. This treatment modality often fails due to local recurrence and persistence of cancer within the radiation field, which severely impacts patients' quality of life and long-term survival[11]. Emerging research highlights the need to identify new molecular targets and pathways that can enhance the radiosensitivity of ESCA cells, which is critical for improving the outcomes of radiotherapy and reducing the high rate of treatment failure[12,13].

Among the key players in tumor biology, Snail family transcriptional repressor 1 (SNAI1) stands out as a pivotal transcription factor implicated in the pathogenesis of various cancers[14,15]. SNAI1 is renowned for its role in driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process integral to cancer progression that facilitates tumor cell invasion, migration, and treatment resistance, including radiotherapy[16,17]. Although the role of SNAI1 in cancer has been extensively documented, its specific involvement in modulating radiosensitivity in ESCA has been less explored. Preliminary studies indicate that SNAI1 may affect the tumor response to radiotherapy through its influence on cellular stress responses, DNA repair mechanisms, and key radiation-related signaling pathways[18,19]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that the interplay between SNAI1 and other EMT-inducing transcription factors, such as ZEB1 and TWIST1, might amplify its impact on treatment resistance, adding a layer of complexity to its biological functions[20].

Our study aimed to comprehensively investigate the relationship between SNAI1 expression and radiation sensitivity in ESCA, exploring its connections not only with EMT but also with other molecular mechanisms that may underlie treatment resistance. To provide a broader perspective, we also compared SNAI1 with alternative therapeutic targets being explored in ESCA, thereby establishing its relative significance in the context of radiosensitization.

In this study, we analyzed SNAI1 expression and its prognostic significance in ESCA using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). We then correlated these findings with the survival outcomes of patients who underwent radiotherapy, integrating clinical data to elucidate the prognostic impact of SNAI1 expression. Our research further validated the role of SNAI1 in modulating radiosensitivity through rigorous in vitro and in vivo experimental models. Additionally, we delve into the mechanisms by which SNAI1 influences EMT and its related processes, with a particular focus on novel aspects of deacetylation. By building on the most recent advancements in cancer biology, including the understanding of EMT dynamics and SNAI1-targeted therapeutic strategies, our study not only contributes to the understanding of the role of SNAI1 but also offers a new theoretical framework for the personalized management of ESCA. Ultimately, we aim to increase the effectiveness of radiotherapy and improve patient survival and quality of life.

RNA-seq expression data for SNAI1 in different cancers were obtained from the TCGA database[21]. The ESCA dataset, including clinical follow-up data, was downloaded for further analysis. The RNA-seq data were initially processed by converting the FPKM format to the TPM format, followed by log2 transformation for statistical analyses using R software. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the differences in expression between tumor tissues and normal tissues. Visualization of the results was conducted using the "ggplot2" R package to enhance interpretability and reproducibility.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to investigate the associations between SNAI1 expression and various clinicopathological characteristics in the TCGA samples, including T classification, N classification, M classification, and clinical stages. In addition, differences in SNAI1 expression were compared between patients treated with and without radiotherapy. To determine whether SNAI1 is associated with the prognosis of patients with ESCA, a log-rank test was conducted on the TCGA dataset to analyze overall survival (OS). Moreover, a separate cohort of 26 ESCA patients from The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University was included to validate the findings. Correlations between SNAI1 expression and clinicopathological parameters, along with patient outcomes such as OS and disease-free survival, were examined. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated using the ‘‘survival” package in R software.

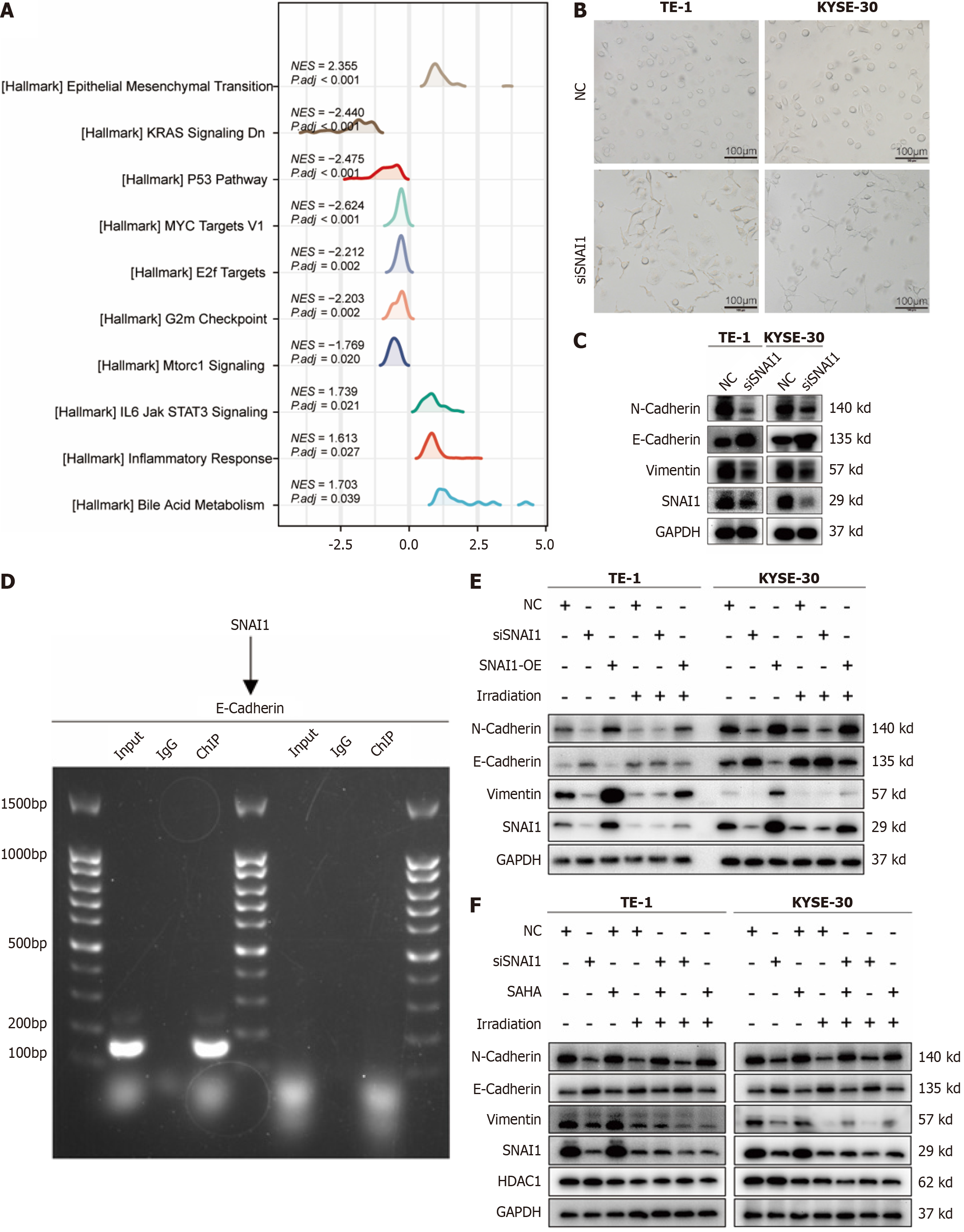

The "DESeq2" R package was used to compare gene expression between the low- and high-SNAI1 subgroups based on TCGA ESCA data. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was then performed using the hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database to identify pathways associated with SNAI1 expression[22]. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 and a |normalized enrichment score (NES)| > 1.

The human ESCA cell lines TE-1, TE-10, and KYSE-30 were procured from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). These cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every other day. Cells were irradiated using a 160 keV Rad Source X-ray generator (Suwanee, GA, United States) with a radiation field of 20 cm × 20 cm and a dose rate of 1 Gy/minute. SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, was utilized to suppress HDAC activity in tumor cells at a concentration of 5 μM (Selleck, United States; S1047).

The TE-1, TE-10, or KYSE-30 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and the protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, China). A total of 10 μg of protein was separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 h and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with a secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Following chemiluminescence development, both the target bands and the internal reference (GAPDH or α-Tubulin) were quantified using Image J software.

The antibodies used in this experiment were as follows: Anti-Snail (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 3879S, 1:1000); anti-N-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 84117S, 1:1000); anti-E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 3195S, 1:1000); anti-vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 5741S, 1:1000); anti-HDAC1 (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 34589S, 1:1000); anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 5174S, 1:1000); and anti-α-Tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 2125S, 1:1000).

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and overexpression plasmids targeting SNAI1 were custom designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Suzhou, China). These were denoted as small interfering SNAI1 (siSNAI1) and SNAI1-OE, respectively. TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells were transfected with 10 nM siRNAs or SNAI1-OE using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, United States). The culture medium was changed 8 h after transfection. The siSNAI1 sequence used was as follows: 5’-UUGUGGAGCAGGGACAUUCTT-3’. The sequences for SNAI1-OE were as follows: ATGCCGCGCTCTTTCCTCGTCAGGAAGCCCTCCGACCCCAATCGGAAGCCTAACTACAGCGAGCTGCAGGACTCTAATCCAGAGTTTACCTTCCAGCAGCCCTACGACCAGGCCCACCTGCTGGCAGCCATCCCACCTCCGGAGATCCTCAACCCCACCGCCTCGCTGCCAATGCTCATCTGGGACTCTGTCCTGGCGCCCCAAGCCCAGCCAATTGCCTGGGCCTCCCTTCGGCTCCAGGAGAGTCCCAGGGTGGCAGAGCTGACCTCCCTGTCAGATGAGGACAGTGGGAAAGGCTCCCAGCCCCCCAGCCCACCCTCACCGGCTCCTTCGTCCTTCTCCTCTACTTCAGTCTCTTCCTTGGAGGCCGAGGCCTATGCTGCCTTCCCAGGCTTGGGCCAAGTGCCCAAGCAGCTGGCCCAGCTCTCTGAGGCCAAGGATCTCCAGGCTCGAAAGGCCTTCAACTGCAAATACTGCAACAAGGAATACCTCAGCCTGGGTGCCCTCAAGATGCACATCCGAAGCCACACGCTGCCCTGCGTCTGCGGAACCTGCGGGAAGGCCTTCTCTAGGCCCTGGCTGCTACAAGGCCATGTCCGGACCCACACTGGCGAGAAGCCCTTCTCCTGTCCCCACTGCAGCCGTGCCTTCGCTGACCGCTCCAACCTGCGGGCCCACCTCCAGACCCACTCAGATGTCAAGAAGTACCAGTGCCAGGCGTGTGCTCGGACCTTCTCCCGAATGTCCCTGCTCCACAAGCACCAAGAGTCCGGCTGCTCAGGATGTCCCCGC.

The immunohistochemistry procedure involved tissue section preparation, deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval, blocking of nonspecific binding sites, incubation with a specific primary antibody, washing, secondary antibody incubation, detection with a chromogenic substrate, counterstaining with hematoxylin, and mounting. The stained sections were subsequently examined under a microscope to evaluate the spatial distribution of the SNAI1 protein. The antibodies used were the same as those used in the Western blot experiments.

TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a volume of 2 mL per well. Once the cells adhered, they were transfected with siSNAI1 for 2 d and subsequently exposed to X-ray irradiation at doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy, corresponding to cell populations of 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1600 cells within the respective dose groups. Following irradiation, the cells were cultured for 14 d. The cells were subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min, after which the cells were counted. Survival curves were fitted using a "single-hit multitarget" model. Relevant parameters, such as the mean lethal dose (D0) and sensitization enhancement ratio (SER), were calculated using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software).

TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells were subjected to siSNAI1 transfection for 24 h, then subsequently exposed to 6 Gy X-ray irradiation. After 48 h of irradiation, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 1 × buffer, and subjected to staining with Annexin V 7AAD/PE staining solution (BD Biosciences, United States) for 15 min in the dark. The cells were then subjected to apoptosis analysis using flow cytometry.

TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells were transfected with siSNAI1 for 24 h, followed by exposure to 6 Gy X-ray irradiation. At 12 h post-irradiation, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (Beyotime, China). The cells were then incubated overnight with a γ-H2AX primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, United States; 9718S, 1:200). The following day, after being washed with tris-buffered saline containing Tween (TBST), the cells were incubated in the dark with a fluorescent secondary antibody (1:1000, Abcam, United Kingdom) for 30 min. The cells were washed with TBST, and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (Beyotime, China). Finally, images were captured using confocal microscopy, and the number of γ-H2AX foci was counted to assess the extent of DNA damage.

Six-week-old male nude mice were procured from SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and maintained in a controlled environment, following the specific pathogen-free animal care protocols of Soochow University. The mice were housed at a constant temperature of 24-26°C with a relative humidity of 50% ± 5%. They adhered to a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle and were provided ad libitum access to sterile food and water. All procedures for animal experimentation were conducted in strict compliance with the regulations set forth by the Research Ethics Committee of Soochow University and adhered to the guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Initially, 1 × 107 TE-1 NC and siSNAI1 cells were subcutaneously implanted into male BALB/c nude mice (6 wks old). Once the tumor volume reached 400 mm³, the TE-1-derived tumors were subjected to 10 Gy X-ray radiotherapy. Radiotherapy for the xenografts was executed using a 160 keV RadSource irradiator (Suwanee, GA, United States) at a dose rate of 1 Gy/min. The tumor volume was determined using the formula (length × width²)/2. Subsequently, the tumor tissues were excised and subjected to analysis.

Tumor tissues were initially fixed with 4% formaldehyde, followed by a series of steps that involved dehydration and clarification with alcohol and xylene. The tissues were subsequently embedded in wax blocks, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin to visualize nuclei and eosin for cytoplasmic features. After the staining process, the sections were dehydrated with alcohol and further clarified with xylene. Finally, the sections were sealed with resin and examined under a microscope for observation and photography.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was conducted to evaluate the interaction between the SNAI1 protein and the regulatory region of the E-cadherin gene. The ChIP procedure included a sequence of stages, including initial cross-linking, cell lysis, chromatin shearing, immunoprecipitation utilizing an anti-protein SNAI1 antibody, subsequent washing, elution, purification, quantification, and eventual analysis via quantitative polymerase chain reaction to assess the degree of SNAI1 protein binding to the E-cadherin gene promoter region.

GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States) was used to perform statistical analyses. The data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences among groups were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Tukey’s test. Each experiment was repeated as three independent experiments unless otherwise specified. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

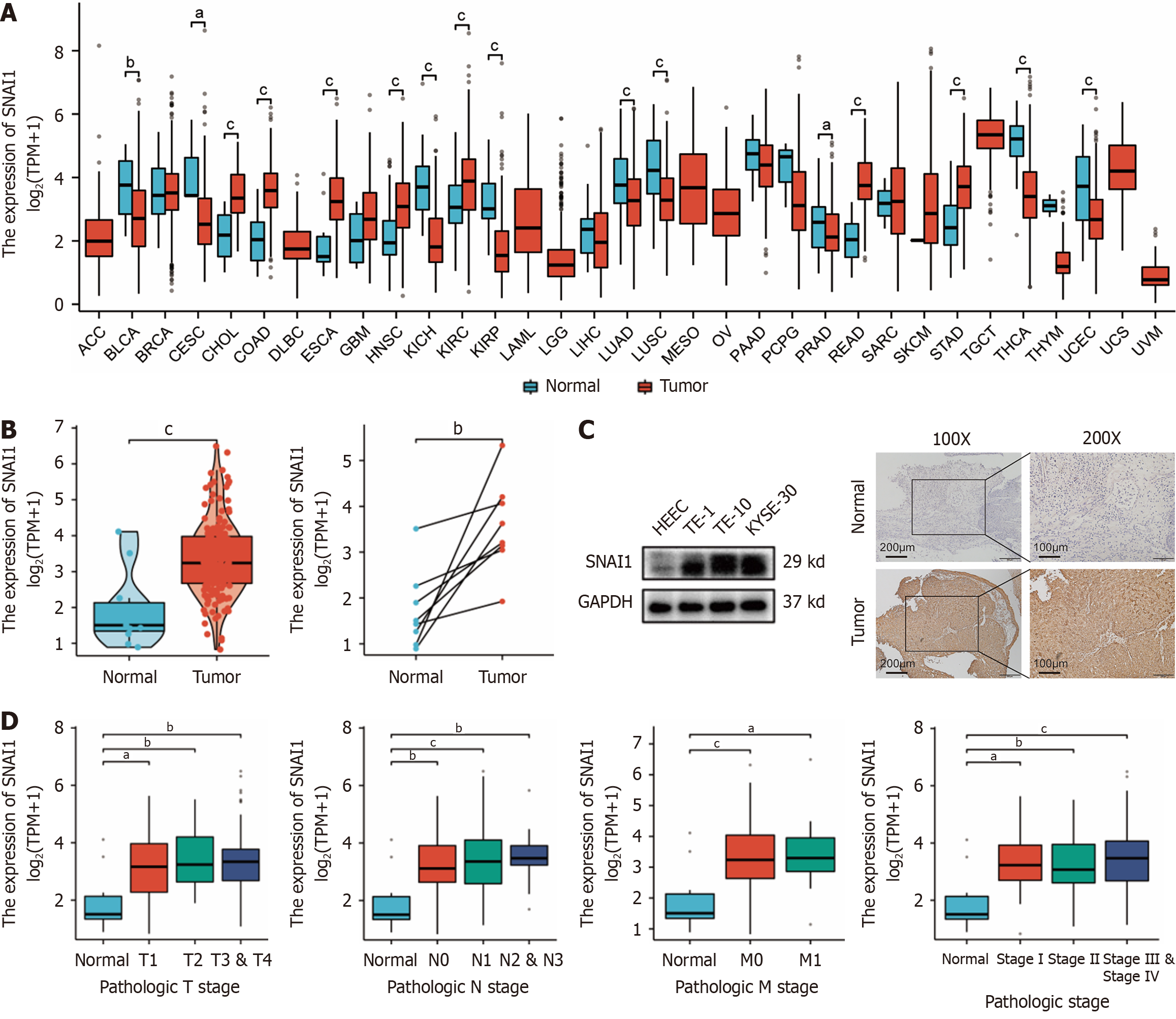

The TCGA database revealed significant differential expression of SNAI1 in various tumors compared with adjacent normal tissues. In ESCA, both unmatched and matched samples presented significantly higher SNAI1 expression in tumor tissues (Figure 1A and B). SNAI1 expression in ESCA cells (TE-1, TE-10, and KYSE-30) was increased compared to normal esophageal epithelial cells in the human esophagus (Figure 1C). Subcutaneous tumor tissues from clinical ESCA patients also demonstrated elevated SNAI1 expression in tumor tissue compared to that in adjacent tissue (Figure 1C). Furthermore, TCGA data revealed upregulated SNAI1 expression in ESCA tissues relative to normal tissues across different TNM stages and pathological grades (Figure 1D).

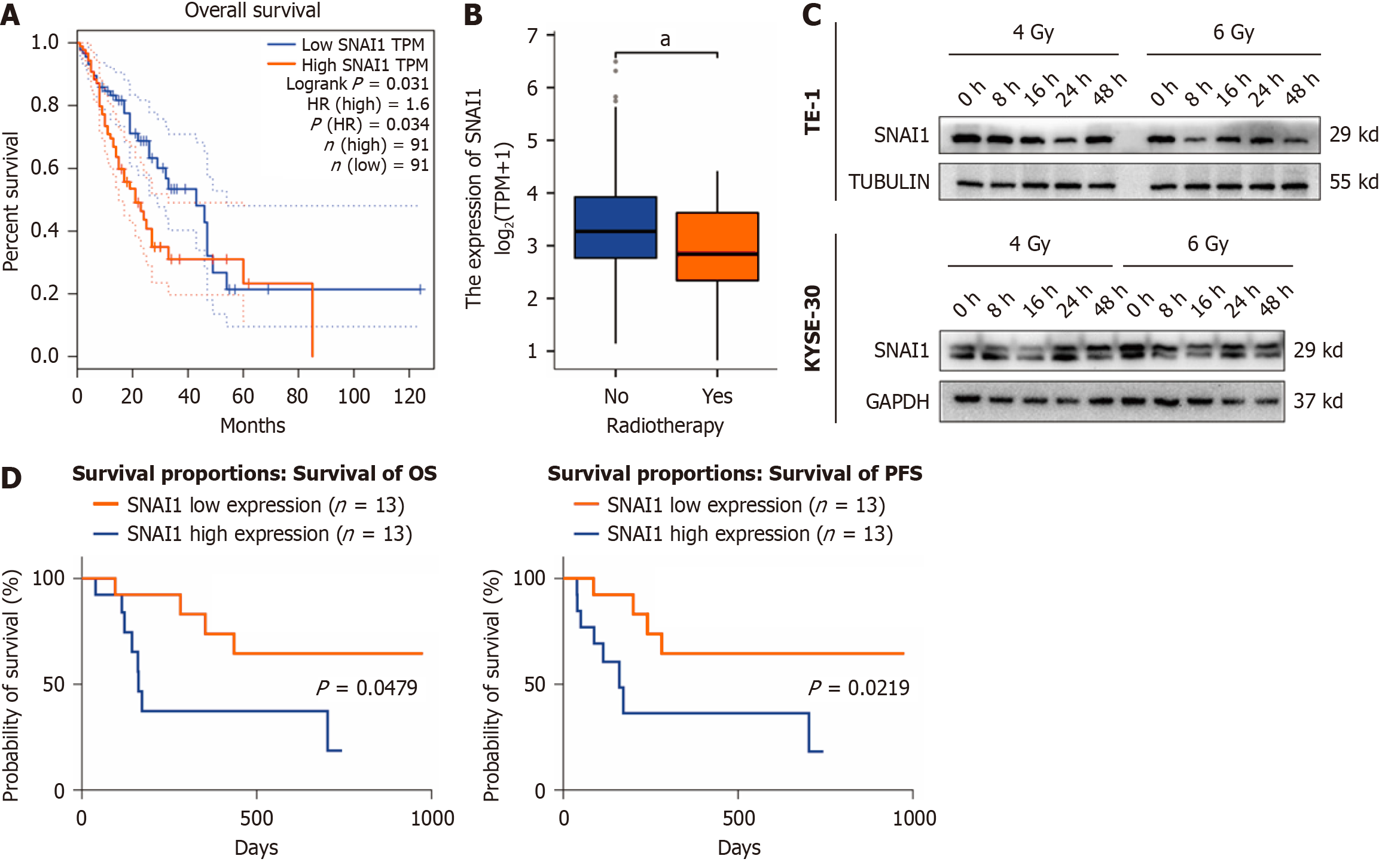

Analysis of TCGA data revealed that patients with high SNAI1 expression had a poorer prognosis (Figure 2A). Moreover, SNAI1 expression was significantly lower in patients who underwent radiotherapy than in those who did not (Figure 2B). We observed a downward trend in SNAI1 expression at different time points after irradiation in TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells with 4 Gy and 6 Gy X-rays (Figure 2C). A cohort of 26 ESCA patients receiving radiotherapy was subjected to immunohistochemical analysis of SNAI1 expression using tissue sections obtained from clinical samples. The analysis of the correlations between SNAI1 expression and clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The results revealed that patients with low SNAI1 expression exhibited a more favorable prognosis following radiotherapy than those with high SNAI1 expression (Figure 2D).

| Clinicopathological factor | High (n = 13) | Low (n = 13) | χ² | P value |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 10 | 11 | 0.2476 | 0.6188 |

| Female | 3 | 2 | ||

| Age | ||||

| < 70 | 10 | 13 | 3.391 | 0.0655 |

| ≥ 70 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well and moderately | 6 | 10 | 2.6 | 0.1069 |

| Poorly | 7 | 3 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| I + II | 3 | 3 | 0 | > 0.99 |

| III + IV | 10 | 10 | ||

| Pre-treatment status | ||||

| Locally advanced + metastatic | 1 | 7 | 6.5 | 0.0108a |

| Local recurrence + Recurrence with distant metastasis | 12 | 6 |

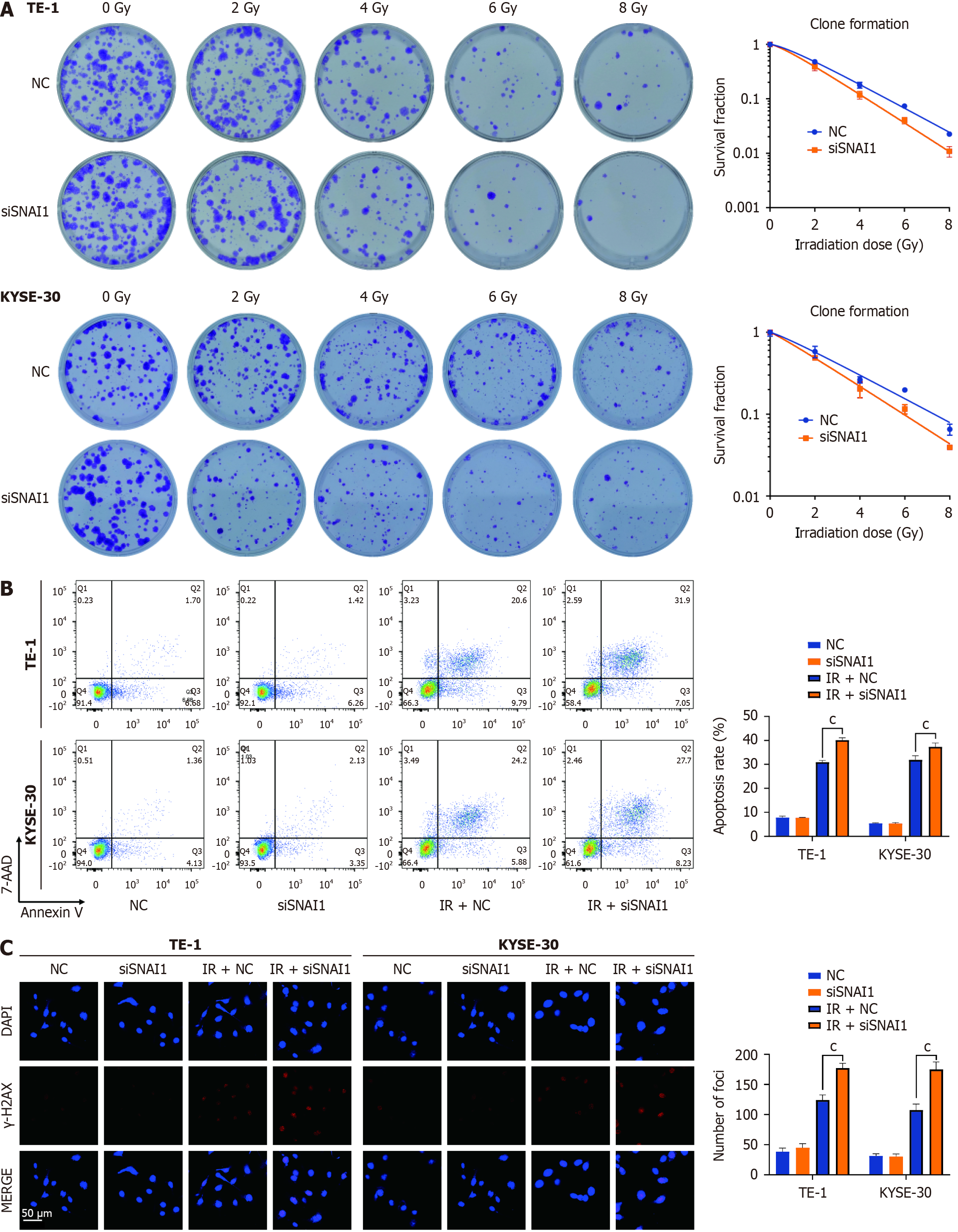

Further investigations involved transfecting siSNAI1 into TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells and subjecting them to different ra

| NC | siSNAI1 | SER | |

| TE-1 | |||

| D0 | 1.954 | 1.642 | 1.19 |

| n | 1.464 | 1.403 | |

| KYSE-30 | |||

| D0 | 2.955 | 2.457 | 1.20 |

| n | 1.193 | 1.129 |

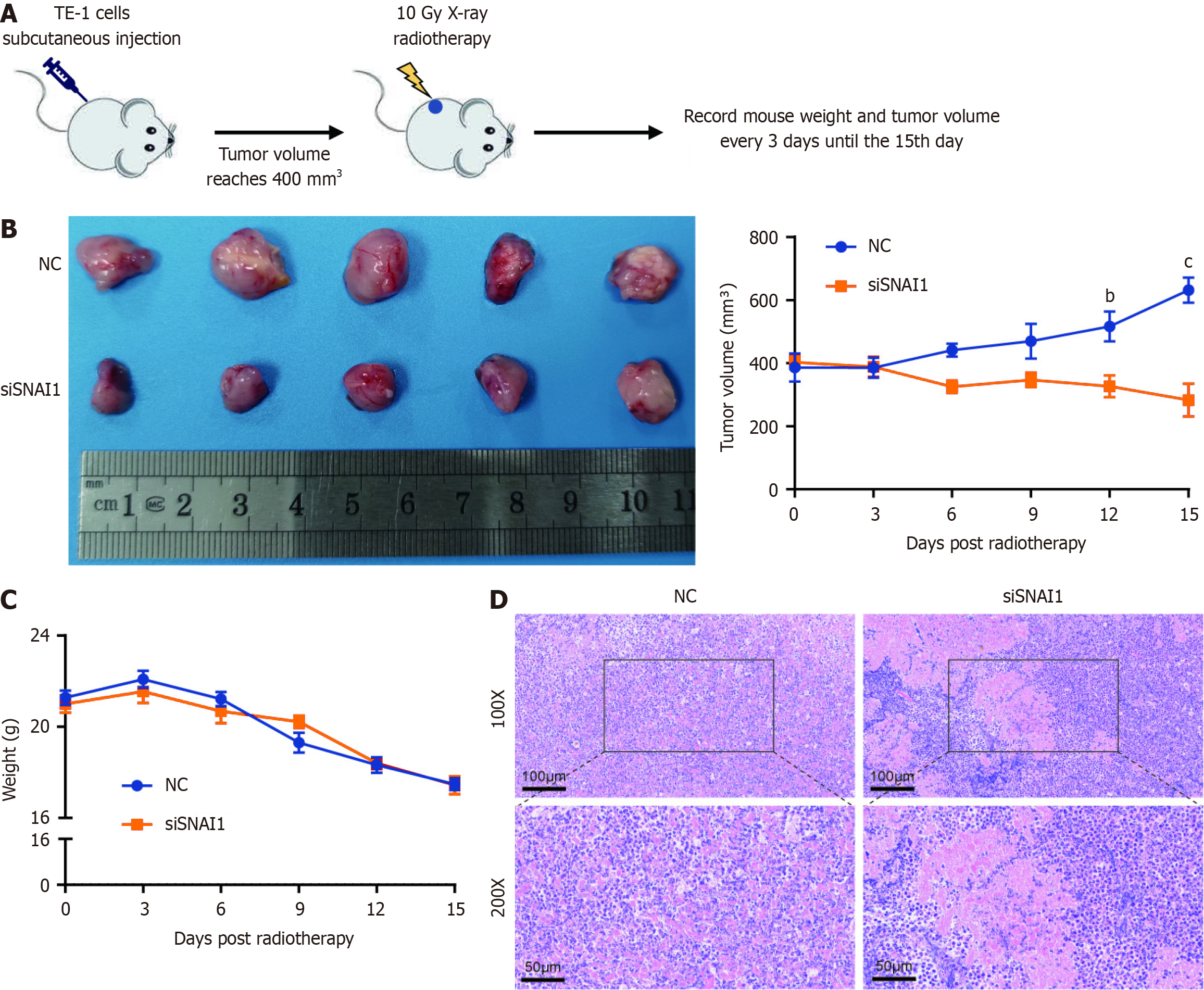

We next established stable TE-1 cell lines with NC and siSNAI1 and generated subcutaneous TE-1 cell xenografts in nude mice. Animals were exposed to radiotherapy (10 Gy X-ray) when the tumor volume reached approximately 400 mm3. We regularly monitored mouse body weight and tumor volume every 3 d (Figure 4A). The tumor volume curve revealed a significantly faster rate of tumor regression in the siSNAI1 group than in the NC group (Figure 4B), with no significant difference in mouse body weight (Figure 4C). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tumor tissues revealed greater necrosis in the siSNAI1 group (Figure 4D).

GSEA of SNAI1 expression in ESCA revealed EMT-related pathways at the forefront (NES = 2.355, P < 0.001; Figure 5A). Morphological changes indicative of EMT were observed under a microscope (Figure 5B). Knocking down SNAI1 in TE-1 and KYSE-30 cells led to reduced N-cadherin and vimentin expression and increased E-cadherin expression (Figure 5C). ChIP experiments confirmed that SNAI1 binds to the E-cadherin promoter region, thereby regulating E-cadherin expre

ESCA remains a critical public health challenge due to its high mortality rates worldwide. The current study elucidates a complex interaction involving the transcription factor SNAI1, which plays a pivotal role in determining the prognosis and radiosensitivity of ESCA patients, thereby deepening the understanding of disease biology and suggesting innovative strategies for clinical management. Recent advances in early detection technologies, such as hyperspectral imaging combined with artificial intelligence, have demonstrated significant accuracy in identifying early ESCA, providing opportunities to enhance patient outcomes through timely interventions[23]. These innovations highlight the importance of integrating cutting-edge diagnostic methods with therapeutic strategies to improve ESCA management.

Our findings confirm that SNAI1 is frequently overexpressed in ESCA tissues, as demonstrated by analyses of TCGA data. This overexpression is strongly correlated with advanced tumor stage and poor survival outcomes, a pattern that is consistent with observations in other cancers, such as breast, pancreatic, and lung cancers. Elevated SNAI1 levels have been linked to increased tumor aggressiveness, enhanced metastatic potential, and poorer prognoses, underscoring its significance in oncogenesis across different cancer types. Importantly, SNAI1 overexpression was also found to modulate the response to radiotherapy, highlighting its dual role as a prognostic marker and a therapeutic target. Moreover, narrow-band imaging algorithms for video capsule endoscopy have enhanced the detection and classification of eso

A pivotal aspect of this research is the strong correlation between SNAI1 expression and radiotherapy outcomes. Analysis of TCGA data reveals that high SNAI1 expression is significantly associated with poorer prognoses in ESCA patients, paralleling its role in treatment resistance in multiple cancers. Additionally, clinical data and

Extending the investigation from

Focusing on the underlying mechanisms, the study underscores the influence of the EMT in mediating SNAI1's effects on radiosensitivity. GSEA revealed that EMT-related pathways are critical contributors to the radioresistant phenotype in ESCA, consistent with their well-established roles in metastasis and therapy resistance across various cancers[28-30]. Downregulation of SNAI1 led to EMT reversal, characterized by restored E-Cadherin expression and reduced expression of mesenchymal markers such as Vimentin and N-Cadherin. ChIP assays confirmed that SNAI1 directly regulates the E-Cadherin promoter, corroborating findings in breast cancer[31] and further demonstrating that IR-induced EMT can be attenuated through SNAI1 inhibition[32].

The study further explores the influence of deacetylation on EMT and its link to SNAI1 function. Deacetylation is mediated by HDACs and has been shown to regulate EMT in breast and lung cancers[33,34]. Our experiments revealed that the HDAC inhibitor SAHA effectively suppressed EMT, reversing SNAI1-driven changes in cellular phenotype. This suggests that deacetylation plays a key role in radiation-induced EMT and highlights HDAC inhibitors as promising agents for preventing treatment resistance in ESCA, as demonstrated in other malignancies[35,36].

A pivotal aspect of this research is the strong correlation between SNAI1 expression and radiotherapy outcomes. Analysis of TCGA data revealed that high SNAI1 expression is significantly associated with poorer prognoses in ESCA patients, paralleling its role in treatment resistance in multiple cancers. Additionally, clinical data and in vitro experiments suggest that downregulation of SNAI1 enhances radiosensitivity and promotes apoptosis post-irradiation, findings that are supported by similar trends in colorectal and hypopharyngeal cancers.

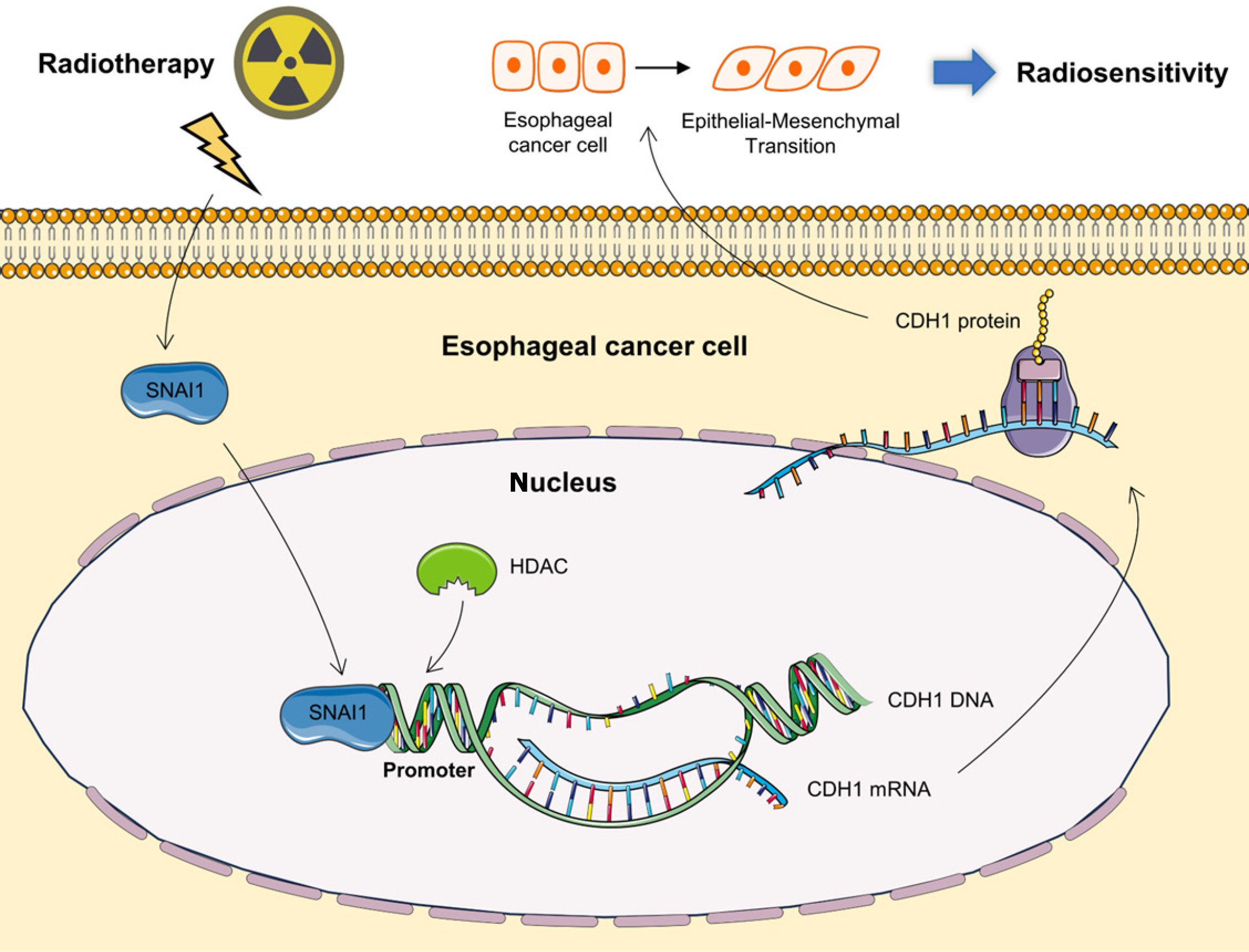

In conclusion, this study reveals the multifaceted role of SNAI1 in ESCA, providing new insights into its relationship with radiotherapy prognosis and radiosensitivity. By demonstrating the direct impact of SNAI1 on EMT and radiosensitivity mechanisms, we established it as both a prognostic marker and a potential therapeutic target. These findings underscore the clinical importance of targeting SNAI1 and provide a foundation for future research exploring its translational applications in personalized cancer therapy. Further studies involving larger patient cohorts and detailed investigations into alternative SNAI1-targeting strategies, including combinatorial treatments with HDAC inhibitors, are warranted to fully realize its therapeutic potential. Ultimately, this study contributes to further elucidating the role of SNAI1 in cancer biology and lays the groundwork for advancing ESCA management, with the goal of improving patient survival and quality of life (Figure 6).

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4235] [Cited by in RCA: 11347] [Article Influence: 3782.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Ma L, Li X, Wang M, Zhang Y, Wu J, He Y, Fan X, Zhang B, Zhou X. The Incidence, Mortality, and DALYs Trends Associated with Esophageal Cancer - China, 1990-2019. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4:956-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baiu I, Backhus L. Esophageal Cancer Surgery. JAMA. 2020;324:1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gil Z, Billan S. Pembrolizumab-chemotherapy for advanced oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2021;398:726-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin SH, Hobbs BP, Verma V, Tidwell RS, Smith GL, Lei X, Corsini EM, Mok I, Wei X, Yao L, Wang X, Komaki RU, Chang JY, Chun SG, Jeter MD, Swisher SG, Ajani JA, Blum-Murphy M, Vaporciyan AA, Mehran RJ, Koong AC, Gandhi SJ, Hofstetter WL, Hong TS, Delaney TF, Liao Z, Mohan R. Randomized Phase IIB Trial of Proton Beam Therapy Versus Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy for Locally Advanced Esophageal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1569-1579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang YM, Hong P, Xu WW, He QY, Li B. Advances in targeted therapy for esophageal cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 61.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, Moletta L, De Pasqual AL, Fornasier C, Salvador R, Zanchettin G, Lonardi S, Galuppo S, Hadzijusufovic E, Grimminger PP, Stocchero M, Costantini M, Merigliano S, Valmasoni M. Multimodal treatment of radiation-induced esophageal cancer: Results of a case-matched comparative study from a single center. Int J Surg. 2022;99:106268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ge F, Huo Z, Cai X, Hu Q, Chen W, Lin G, Zhong R, You Z, Wang R, Lu Y, Wang R, Huang Q, Zhang H, Song A, Li C, Wen Y, Jiang Y, Liang H, He J, Liang W, Liu J. Evaluation of Clinical and Safety Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Combined With Chemotherapy for Patients With Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2239778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ji Y, Du X, Zhu W, Yang Y, Ma J, Zhang L, Li J, Tao H, Xia J, Yang H, Huang J, Bao Y, Du D, Liu D, Wang X, Li C, Yang X, Zeng M, Liu Z, Zheng W, Pu J, Chen J, Hu W, Li P, Wang J, Xu Y, Zheng X, Chen J, Wang W, Tao G, Cai J, Zhao J, Zhu J, Jiang M, Yan Y, Xu G, Bu S, Song B, Xie K, Huang S, Zheng Y, Sheng L, Lai X, Chen Y, Cheng L, Hu X, Ji W, Fang M, Kong Y, Yu X, Li H, Li R, Shi L, Shen W, Zhu C, Lv J, Huang R, He H, Chen M. Efficacy of Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy With S-1 vs Radiotherapy Alone for Older Patients With Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Phase 3 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1459-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shitara K, Rha SY, Wyrwicz LS, Oshima T, Karaseva N, Osipov M, Yasui H, Yabusaki H, Afanasyev S, Park YK, Al-Batran SE, Yoshikawa T, Yanez P, Dib Bartolomeo M, Lonardi S, Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Janjigian YY, Oh DY, Xu J, Fang X, Shih CS, Bhagia P, Bang YJ; KEYNOTE-585 investigators. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-585): an interim analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:212-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 127.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen D, Menon H, Verma V, Seyedin SN, Ajani JA, Hofstetter WL, Nguyen QN, Chang JY, Gomez DR, Amini A, Swisher SG, Blum MA, Younes AI, Barsoumian HB, Erasmus JJ, Lee JH, Bhutani MS, Hess KR, Minsky BD, Welsh JW. Results of a Phase 1/2 Trial of Chemoradiotherapy With Simultaneous Integrated Boost of Radiotherapy Dose in Unresectable Locally Advanced Esophageal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou X, Gao F, Gao W, Wang Q, Li X, Li X, Li W, Liu J, Zhou H, Luo A, Chen C, Liu Z. Bismuth Sulfide Nanoflowers Facilitated miR339 Delivery to Overcome Stemness and Radioresistance through Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 8 in Esophageal Cancer. ACS Nano. 2024;18:19232-19246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang XW, Yang ZY, Li T, Zhao XR, Li XZ, Wang XX. Verteporfin Exerts Anticancer Effects and Reverses Resistance to Paclitaxel via Inducing Ferroptosis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Cancer Cells. Mol Biotechnol. 2024;66:2558-2568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jung HY, Fattet L, Tsai JH, Kajimoto T, Chang Q, Newton AC, Yang J. Apical-basal polarity inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis by PAR-complex-mediated SNAI1 degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang X, Liu R, Zhu W, Chu H, Yu H, Wei P, Wu X, Zhu H, Gao H, Liang J, Li G, Yang W. UDP-glucose accelerates SNAI1 mRNA decay and impairs lung cancer metastasis. Nature. 2019;571:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang Y, Hong W, Wei X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 458] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Debaugnies M, Rodríguez-Acebes S, Blondeau J, Parent MA, Zocco M, Song Y, de Maertelaer V, Moers V, Latil M, Dubois C, Coulonval K, Impens F, Van Haver D, Dufour S, Uemura A, Sotiropoulou PA, Méndez J, Blanpain C. RHOJ controls EMT-associated resistance to chemotherapy. Nature. 2023;616:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shen X, Deng Y, Chen L, Liu C, Li L, Huang Y. Modulation of Autophagy Direction to Enhance Antitumor Effect of Endoplasmic-Reticulum-Targeted Therapy: Left or Right? Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2301434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kochanowski P, Catapano J, Pudełek M, Wróbel T, Madeja Z, Ryszawy D, Czyż J. Temozolomide Induces the Acquisition of Invasive Phenotype by O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT)(+) Glioblastoma Cells in a Snail-1/Cx43-Dependent Manner. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Čugura T, Boštjančič E, Uhan S, Hauptman N, Jeruc J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition associated markers in sarcomatoid transformation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2024;138:104909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hutter C, Zenklusen JC. The Cancer Genome Atlas: Creating Lasting Value beyond Its Data. Cell. 2018;173:283-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 496] [Article Influence: 70.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Geistlinger L, Csaba G, Santarelli M, Ramos M, Schiffer L, Turaga N, Law C, Davis S, Carey V, Morgan M, Zimmer R, Waldron L. Toward a gold standard for benchmarking gene set enrichment analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22:545-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang KY, Mukundan A, Tsao YM, Shi XH, Huang CW, Wang HC. Assessment of hyperspectral imaging and CycleGAN-simulated narrowband techniques to detect early esophageal cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13:20502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fang YJ, Huang CW, Karmakar R, Mukundan A, Tsao YM, Yang KY, Wang HC. Assessment of Narrow-Band Imaging Algorithm for Video Capsule Endoscopy Based on Decorrelated Color Space for Esophageal Cancer: Part II, Detection and Classification of Esophageal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu Y, Wang C, Becker SA, Hurst K, Nogueira LM, Findlay VJ, Camp ER. miR-145 Antagonizes SNAI1-Mediated Stemness and Radiation Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Mol Ther. 2018;26:744-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang H, Wang Z, Li Y, Lu T, Hu G. Silencing Snail Reverses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Increases Radiosensitivity in Hypopharyngeal Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:497-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mezencev R, Matyunina LV, Jabbari N, McDonald JF. Snail-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of MCF-7 breast cancer cells: systems analysis of molecular changes and their effect on radiation and drug sensitivity. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Paul MC, Schneeweis C, Falcomatà C, Shan C, Rossmeisl D, Koutsouli S, Klement C, Zukowska M, Widholz SA, Jesinghaus M, Heuermann KK, Engleitner T, Seidler B, Sleiman K, Steiger K, Tschurtschenthaler M, Walter B, Weidemann SA, Pietsch R, Schnieke A, Schmid RM, Robles MS, Andrieux G, Boerries M, Rad R, Schneider G, Saur D. Non-canonical functions of SNAIL drive context-specific cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2023;14:1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lüönd F, Sugiyama N, Bill R, Bornes L, Hager C, Tang F, Santacroce N, Beisel C, Ivanek R, Bürglin T, Tiede S, van Rheenen J, Christofori G. Distinct contributions of partial and full EMT to breast cancer malignancy. Dev Cell. 2021;56:3203-3221.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 55.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Song J, Lin Z, Liu Q, Huang S, Han L, Fang Y, Zhong P, Dou R, Xiang Z, Zheng J, Zhang X, Wang S, Xiong B. MiR-192-5p/RB1/NF-κBp65 signaling axis promotes IL-10 secretion during gastric cancer EMT to induce Treg cell differentiation in the tumour microenvironment. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12:e992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xie W, Jiang Q, Wu X, Wang L, Gao B, Sun Z, Zhang X, Bu L, Lin Y, Huang Q, Li J, Guo J. IKBKE phosphorylates and stabilizes Snail to promote breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:1528-1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim SY, Shin MS, Kim GJ, Kwon H, Lee MJ, Han AR, Nam JW, Jung CH, Kang KS, Choi H. Inhibition of A549 Lung Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion by Ent-Caprolactin C via the Suppression of Transforming Growth Factor-β-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Mar Drugs. 2021;19:465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yang Y, Zhao B, Lv L, Yang Y, Li S, Wu H. FBXL10 promotes EMT and metastasis of breast cancer cells via regulating the acetylation and transcriptional activity of SNAI1. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wang Y, Ha M, Li M, Zhang L, Chen Y. Histone deacetylase 6-mediated downregulation of TMEM100 expedites the development and progression of non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Cell. 2022;35:271-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jo H, Shim K, Kim HU, Jung HS, Jeoung D. HDAC2 as a target for developing anti-cancer drugs. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:2048-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chen T, Li K, Liu Z, Liu J, Wang Y, Sun R, Li Z, Qiu B, Zhang X, Ren G, Xu Y, Zhang Z. WDR5 facilitates EMT and metastasis of CCA by increasing HIF-1α accumulation in Myc-dependent and independent pathways. Mol Ther. 2021;29:2134-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |