Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103591

Revised: January 24, 2025

Accepted: February 25, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 121 Days and 14.7 Hours

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, which predominantly manifest in the stomach, colorectum, liver, esophagus, and pancreas, accounting for approximately 35% of global cancer-related mortality. The advent of liquid biopsy has introduced a pivotal diagnostic modality for the early identification of premalignant GI lesions and incipient cancers. This non-invasive technique not only facilitates prompt therapeutic intervention, but also serves as a critical adjunct in prognosticating the likelihood of tumor recurrence. The wealth of circulating exosomes present in body fluids is often enriched with proteins, lipids, microRNAs, and other RNAs derived from tumor cells. These specific cargo components are reflective of processes involved in GI tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and response to treatment. As such, they represent a group of promising biomarkers for aiding in the diagnosis of GI cancer. In this review, we delivered an exhaustive overview of the composition of exosomes and the pathways for cargo sorting within these vesicles. We laid out some of the clinical evidence that supported the utilization of exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers for GI cancers and discussed their potential for clinical application. Furthermore, we addressed the challenges encountered when harnessing exosomes as diagnostic and predictive instruments in the realm of GI cancers.

Core Tip: In this comprehensive review, we explore the innovative potential of exosomal biomarkers in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal (GI) cancers. Liquid biopsy, a non-invasive diagnostic approach, has revolutionized early detection of GI cancers by leveraging the presence of exosomes in body fluids. These exosomes, rich in tumor-derived proteins, lipids, microRNAs, and RNAs, serve as reflective indicators of tumorigenesis and progression. Our analysis underscores the diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive value of exosomes, while also highlighting the clinical evidence supporting their application. We critically discuss the challenges in utilizing exosomes as biomarkers and their implications for early diagnosis, molecular analysis in GI cancers.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Yue NN, Chen LY, Tian CM, Yao J, Wang LS, Liang YJ, Wei DR, Ma HL, Li DF. Exosomal biomarkers: A novel frontier in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancers. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 103591

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/103591.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.103591

As societal and economic progress unfolds, malignant tumors have surfaced as a substantial public health issue, exerting a profound impact on human life and societal advancement. In recent years, there’s been an alarming increase in the prevalence of malignant tumors targeting the gastrointestinal (GI) system, including gastric, esophageal, pancreatic, liver, and colorectal cancers (CRCs)[1]. Consequently, early diagnosis and intervention are pivotal strategies in improving the prognosis of patients battling GI tumors[2].

Amidst the advancement of medical research, exosomes have been identified as playing a pivotal role in tumor development[3]. Their present and potential clinical applications have become integral to the diagnosis and treatment of GI tumors[4]. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), structured with a phospholipid membrane and released by cells into the extracellular matrix, can be classified based on origin, size, and composition into categories including exosomes (30-150 nm), microvesicles (100 nm - 1 μm), and apoptotic bodies (50-5000 nm). Rich in various bioactive substances, predominantly nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins, these vesicles play an essential role in intercellular communication and physiological regulation[5].

Exosomes are secreted by diverse organs, tissues, and cell types within the human body and can be found in cell culture fluid, blood, milk, urine, saliva, joint fluid, and other bodily fluids[6,7]. The types and quantities of exosomes are intimately tied to the body’s physiological state. Owing to their small size (30-150 nm), they can be conveyed through blood and body fluids, linking different molecules within exosomes to tumor metastasis and cardiovascular development[5].

Studies have revealed that serum exosomal circular RNA (circRNA) can differentiate cancer patients from healthy individuals, underscoring the diagnostic potential of exosomes for cancer[8]. This finding propels the possibilities for tumor liquid biopsy, paving the way for promising approaches to cancer diagnosis and treatment[9]. The versatility and potential of exosomes, acting as conduits of vital information in intercellular communication, position them as an exciting frontier in medical research and diagnostics.

This article presented a comprehensive introduction to exosomes, emphasizing their biology and functions. It provided an overview of both traditional and novel technologies used for exosome extraction and content detection. A deep understanding of these techniques could engender standardization in exosomal research, inching the use of exosomes in clinical settings closer to reality. Moreover, the article encapsulated the significant role of exosomes in the diagnosis and treatment of GI tumors. It surveyed current exosomal markers displaying potential for diagnosing GI tumors. By examining the prospects and challenges connected to the application of exosomes in the diagnosis of GI tumors, we aimed to illuminate the potential advantages and constraints of employing exosomes in this realm. In conclusion, this comprehensive article aimed to enhance our knowledge of exosomes, their extraction, and detection methods and highlight their significance in the diagnosis and treatment of GI tumors.

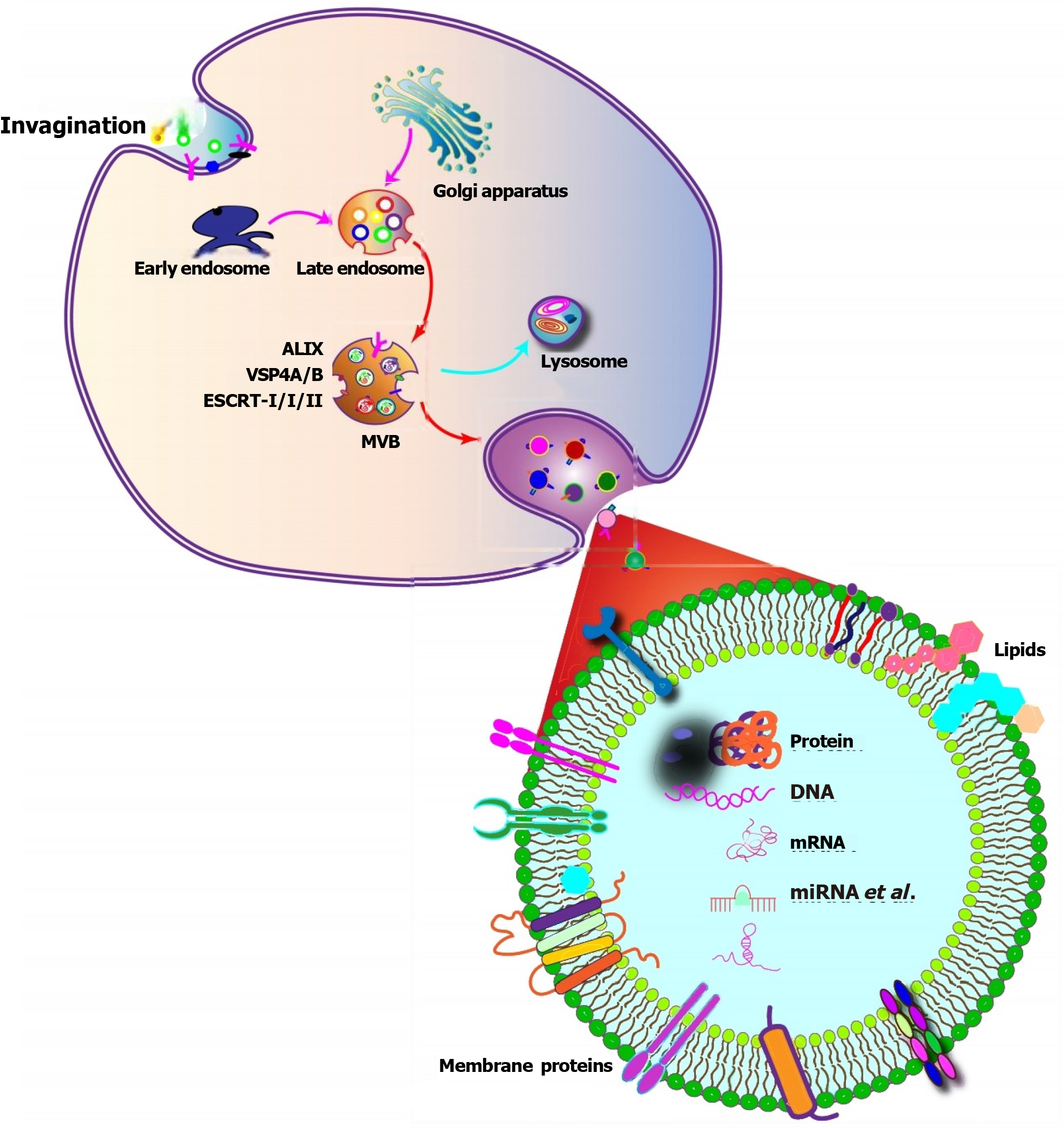

Exosomes are derived from endosomal structures, which originate through endocytosis (Table 1). The process begins with invaginated endosomes forming from the plasma membrane[10] (Figure 1). This is followed by a tightly regulated process that involves active sorting and packaging of the exosomal content[11,12]. The contents of exosomes are diverse and include lipids, proteins, DNA, mRNA, short single-stranded microRNAs (miRNAs) with a length of 18-25 nucleotides (nt), long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) that are greater than 200 nt in length, and novel circRNA[11,13,14]. Exosomes contain various types of proteins, such as Rab family proteins, sorting-associated proteins, tetraspanins, heat shock proteins (HSPs), integrins, and vacuolar proteins. These proteins can be present in the same cell type, or they may co-exist in different cell types, depending on the specific proteins being transported into the exosomes and their respective functions[15].

| Aspect | Details | Ref. |

| Origin | Derived from endosomal structures through endocytosis | [10] |

| Invaginated endosomes form from the plasma membrane | ||

| Content sorting & packaging | Tightly regulated process of active sorting and packaging of diverse contents | [11,12] |

| Diverse contents | Lipids, proteins, DNA, mRNA, miRNAs (18-25 nt), lncRNA (> 200 nt), circRNA | [11,13,14] |

| Protein components | Rab family proteins, sorting - associated proteins, tetraspanins, HSPs, integrins, vacuolar proteins. Co-existence depends on specific proteins and their functions | [15] |

| ESCRT - dependent biogenesis | ESCRT-0 recognizes ubiquitinated cargo, starting the pathway | [16-19] |

| Tsg101 in ESCRT-I forms a complex with ubiquitinated cargo, activating ESCRT-II | ||

| ESCRT-II leads to ESCRT - III formation etc. | ||

| ESCRT-III recruits deubiquitination machinery, packages cargo, promotes vesicle budding. Inward buds mature into MVBs | ||

| ESCRT-III is degraded by an ATPase, regulated by Rab family proteins | ||

| Tetraspanins’ role | Transmembrane proteins that induce membrane - curved structures for vesicle formation | [20] |

| HSPs’ role | Mediate protein distribution in ILVs (exosome precursors) and include cytoskeleton proteins | [21,22] |

| RNA - related features | Enrichment of miRNAs with 3’-end nucleotide additions and 5’-terminal oligopyrimidine | [23-26] |

| Specific RNA modifications during exosome formation enrich specific RNA species | ||

| RNAs can induce genetic and epigenetic modifications in recipient cells | ||

| Lipid structure | Cholesterol, phospholipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, ceramides form a stable bilayer membrane for exosomes | [27] |

Certain proteins play vital roles in exosome biogenesis. The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) is a classic mechanism involved in exosome formation. Acting as a machine for the recognition of ubiquitinated cargo and membrane deformation, the ESCRT pathway starts with ESCRT-0 recognizing ubiquitinated cargo, initiating the pathway[16]. Tumor susceptibility gene 101, a component of the ESCRT-I complex, forms a complex with ubiquitinated cargo proteins, activating the ESCRT-II complex, leading to oligomerization and the formation of the ESCRT-III complex[17]. Subsequently, ESCRT-III recruits deubiquitination machinery, packages cargo into maturing vesicles, and promotes vesicle budding[18]. These inward buds further mature into multivesicular bodies (MVBs)[19]. MVBs develop through inward invagination of the endosomal membrane, forming numerous blebs within these MVBs, known as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs)[10]. These ILV-containing MVBs can undergo a specific exocytotic process, fusing with the plasma membrane and releasing the exosomes. Alternatively, the ESCRT-III complex plays a crucial role in the requisitioning of MVB proteins and the enrollment of enzymes that remove the ubiquitin tag from cargo proteins before placing them into the ILVs. Finally, the ESCRT-III complex is degraded by an ATPase[17], regulated by specific proteins belonging to the Rab family. Additionally, transmembrane proteins called tetraspanins induce membrane-curved structures, enabling vesicle formation[20]. Exosomes may also contain various HSPs (Hsc70, Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp90)[21]. These HSPs mediate protein distribution in ILVs (exosome precursors) and include cytoskeleton proteins, such as actin, tubulin, and cofilin[22]. Moreover, exosome cargo comprises mRNA, DNA, miRNA, and lncRNA. Some studies have found enrichment of miRNAs with 3’-end nucleotide additions and 5’-terminal oligopyrimidine, which reflects specific RNA modifications during exosome formation[23,24]. The specific mechanism underlying exosome biogenesis and content loading due to these selected RNAs enriches specific RNA species[25]. At the same time, these RNAs can induce genetic and epigenetic modifications in recipient cells, influencing their activity and functions[26]. Furthermore, lipids, including cholesterol, phospholipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and ceramides, form a stable bilayer membrane structure essential for exosomes[27].

Exosomes are enveloped by a bimolecular lipid membrane and comprise a diverse range of components, including proteins, lipids, short peptide chains, mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA (Table 2). These components are closely associated with the cells from which the exosomes originate and reflect their specific state[28].

| Biomolecule | Function | Ref. |

| Hsc70, Hsp70, Hsp60, Hsp90 (HSPs) | Mediate protein distribution in ILVs (exosome precursors) and the inclusion of cytoskeleton proteins | [21,22,31] |

| GTPase Rab, flotillins, annexins, ARF6 | Participate in exosome release and membrane fusion | [32,33] |

| Major histocompatibility complex class II molecules | Function not detailed in this text, likely related to immune response | [34] |

| Programmed cell death 6-interacting proteins | Play a role in programmed cell death | [35] |

| Tsg101 proteins | Are involved in the sorting and transportation of exosomes | [22] |

| CD9, CD63, CD81 (tetraspanin family transmembrane proteins) | Function not fully described, likely related to exosome structure and function | [35] |

| Transforming growth factor-β, apoptosis - related factor ligands (in tumor cell secreted exosomes) | Associated with tumor - specific processes | [36] |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase IV, matrix metallopeptidase 9 | Participate in extracellular matrix remodeling, related to tumor invasion and metastasis | [37] |

| Epithelial cell adhesion molecule, epidermal growth factor receptor, survivin, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | Can be used as biomarkers for clinical diagnosis and prognosis | [38] |

| miRNA | Intercellular transport via exosomes may critically regulate gene expression and protein translation | [36,39-44] |

| Short sequence motifs (EXOmotifs) guide miRNA into exosomes | ||

| hnRNPA2B1 selectively binds miRNA, recognizing EXOmotifs and controlling its encapsulation within exosomes | ||

| RNA binding proteins and RNA sequence motifs contribute to its selective sorting into exosomes | ||

| Encapsulated in exosomes, RNA binding proteins protect miRNA from hydrolytic degradation, enabling it to exercise effects through cell-to-cell communication | ||

| circRNA | Part of the diverse ncRNA species in exosomes; specific functions not elaborated in the given text | [39,40] |

| lncRNA | Part of the diverse ncRNA species in exosomes; specific functions not elaborated in the given text | [39,40] |

| EXOmotifs | Guide miRNA into exosomes | [42] |

| hnRNPA2B1 | Selectively binds exosomal miRNAs, recognizes EXOmotifs, and controls their encapsulation within exosomes | [42] |

| RNA binding proteins | Contribute to the selective sorting of miRNA into exosomes and protect RNAs (including miRNA) from hydrolytic degradation when encapsulated in exosomes | [36,43] |

| Cholesterol | Involved in exosome formation and release; contributes to the overall lipid composition affecting exosome properties, though its concentration may differ from parent cells | [32,45-47] |

| Sphingolipids (incl. Sphingomyelin) | Involved in exosome formation and release; sphingomyelin has a higher concentration in exosomes compared to parent cells | [32,45-47] |

| Phosphatidylcholine | Participates in exosome formation and release; present at a reduced content in exosomes relative to parent cells | [32,45-47] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | Involved in exosome formation and release; shows an observable enrichment in exosomes | [32,45-47] |

| Ceramide | Plays a role in exosome formation and release | [32,45,46] |

| Glycerophospholipids | Contribute to exosome formation and release | [32,45,46] |

| Lipid rafts | Implicated in exosome formation and help facilitate the secretion of specific molecules into the extracellular space; contribute to exosome’s permeability and circulating stability, making exosomes suitable for drug delivery | [45,48,27] |

The protein content of exosomes is reflective of their origin in endosomes and varies depending on the type of parent cell[29,30]. All exosomes from diverse cell types carry a few common combinations of proteins, including: (1) HSPs, such as Hsc70, Hsp70, Hsp60, and Hsp90, which mediate protein distribution in ILVs (exosome precursors) and inclusion of cytoskeleton proteins[21,22,31]; (2) GTPase Rab, flotillins, annexins, and ADP ribosylation factor 6 proteins involved in exosome release and membrane fusion[32,33]; (3) Major histocompatibility complex class II molecules[34]; (4) Programmed cell death 6-interacting proteins participating in programmed cell death[35]; (5) Tumor susceptibility gene 101 proteins involved in sorting and transporting exosomes[22]; (6) Transmembrane proteins from the tetraspanin family, such as CD9, CD63, and CD81[35]; and (7) Proteins with a specific cellular origin, for instance, transforming growth factor-β and apoptosis-related factor ligands present in exosomes secreted by tumor cells[36]. Exosomes also express proteins from the dipeptidyl peptidase IV and matrix metallopeptidase 9 families, involved in extracellular matrix remodeling. This association with tumor invasion and metastasis highlights the significance of exosomes in disease progression[37]. Furthermore, certain disease-related proteins, including epithelial cell adhesion molecule, epidermal growth factor receptor, survivin, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, are distributed on the surface of exosomes and can be utilized as biomarkers in clinical diagnosis and prognosis[38].

Numerous studies affirm the diverse array of ncRNA species found in exosomes, including miRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA[39,40]. Evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies suggests that the intercellular transport of functional RNA via exosomes may critically regulate gene expression and protein translation[41]. A particular mechanism involves the encapsulation and exportation of exosomal miRNAs, where short sequence motifs, referred to as EXOmotifs, guide miRNA into exosomes[42]. The heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2B1 selectively binds exosomal miRNAs, recognizing these motifs and controlling their encapsulation within exosomes. This mechanism provides significant insight into the process of miRNA loading and exportation from cells. Furthermore, certain studies suggest that RNA binding proteins and RNA sequence motifs contribute to the selective sorting of miRNA into exosomes[43]. Encapsulated within exosomes, RNA binding proteins play a pivotal role in preserving the normal structure and functionality of RNAs, thereby safeguarding them against hydrolytic degradation[36]. This protective attribute of exosomes enables bioactive RNAs to exercise their effects through cell-to-cell communication[44].

Recent research has demonstrated that exosomes, in addition to harboring proteins and nucleic acids, also contain various lipid species that are instrumental in preserving their biological activity[45]. The specific lipid composition of exosomes[46], including cholesterol, sphingolipids, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, ceramide, and glycerophospholipids[32], is involved in their formation and release. However, it’s important to underscore that the lipid composition of exosomes can diverge from that of their parent cells[47]. For example, exosomes have a higher concentration of sphingomyelin, but not cholesterol, compared to their originating cells. The content of phosphatidylcholine is reduced, while there is an observable enrichment of desaturated molecular species, such as phosphatidylethanolamine. Additionally, exosome membranes can carry lipid rafts derived from the plasma membrane. These lipid rafts are implicated in exosome formation and facilitate the secretion of specific molecules into the extracellular space[48]. The distinctive lipid composition and the stable membrane structure of exosomes enhance their permeability and circulating stability. This makes them an ideal candidate for use as carriers in drug delivery applications[27].

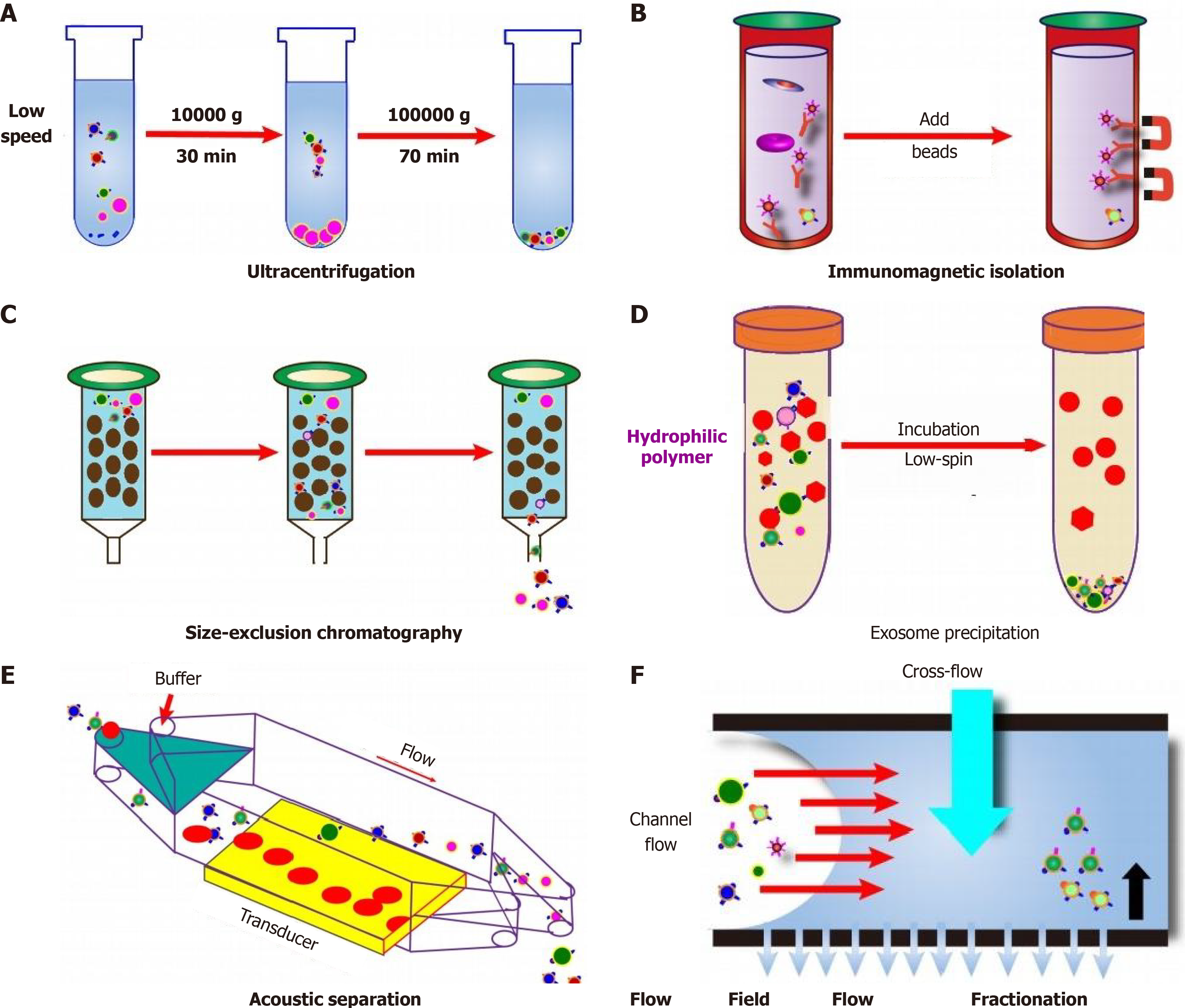

Exosome isolation from liquid biopsies presents significant challenges due to their unique formation and delivery processes, along with their relatively low concentration in biological fluids[49,50]. This situation complicates not only their isolation but also their detection and subsequent analysis. Multiple techniques exist to isolate exosomes, leveraging their physical properties (size, density, surface composition, and exosome precipitation), electromagnetic characteristics, or immunological properties[49,51,52]. Various methods possess their advantages and disadvantages during the extraction of exosome, therefore which are listed in the Table 3.

| Isolation method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

| Ultracentrifugation | Considered the gold standard; convenient and cost - effective; can be combined with density - gradient mechanisms to achieve high - purity exosome yield and aid in morphological identification | Co-purifies lipoproteins and protein aggregates alongside EVs; combined with density - gradient mechanisms may result in lower yield and longer processing time | [53-59] |

| Ultrafiltration | Simple, faster procedure, no need for specialized equipment; refined method can achieve higher capture efficiency of different - sized exosomes compared to ultracentrifugation | Low recovery rate due to protein contamination and potential exosome damage during filtration; filter clogging can occur | [55,57,60-62] |

| Polymer - based precipitation separation (using PEG) | Simple and scalable | Pellets may be contaminated with other particles, large aggregates, and associated proteins, potentially affecting subsequent analysis | [58,63] |

| Microfluidic technology | Promising for rapid, efficient exosome isolation; can achieve high recovery rate in a short time | Not suitable for large - volume sample separation due to handling limitations | [49,64] |

| Other techniques (chromatography, hydrostatic filtration dialysis, size - exclusion chromatography, lipid - based separation, immunoaffinity - based methods) | Allow for seamless integration with clinical diagnostics, broadening potential clinical applications of exosomes | N/A | [49] |

Ultracentrifugation (UC) is currently considered the gold standard for exosome isolation (Figure 2)[53]. During UC, a heterogeneous mixture is subjected to centrifugal force, precipitating particles based on their density, size, and shape[54]. This process separates particles according to their physical attributes and the density and viscosity of the solvent[55]. Despite its convenience and cost-effectiveness, UC has limitations, including the co-purification of lipoproteins and protein aggregates alongside EVs[56]. To overcome this, UC can be combined with density-gradient mechanisms, using either sucrose or iodixanol, to allow EVs to congregate at a particular density through extended centrifugation[57,58]. This approach provides a high-purity exosome yield and aids in their morphological identification but may result in a lower yield and longer processing time[59].

Ultrafiltration is another technique that utilizes a series of microfilters with decreasing sizes ranging from 0.8 to 0.1 μm[55,57]. In a study, the method was refined through the use of a cascade of membranes with varying pore sizes, enabling rapid separation of exosomes of different sizes and achieving higher capture efficiency compared to UC[60]. Despite its advantages, such as simplicity, faster procedure, and no need for specialized equipment, the ultrafiltration method may yield a low recovery rate due to protein contamination and potential exosome damage during filtration. Additionally, filter clogging can occur[61,62]. Based on exosomes’ chemical properties, a polymer-based precipitation separation method can be used. This technique involves polymers, often polyethylene glycol, as precipitating agents[63]. Despite its simplicity and scalability, this method may yield pellets contaminated with other particles, large aggregates, and associated proteins, potentially affecting subsequent analysis[58].

Microfluidic technology represents a promising approach for rapid, efficient exosome isolation (Figure 2). This method uses microfluidic chips to exploit the physical and biochemical properties of exosomes on a microscale. Notably, Woo et al[64] have demonstrated an automated enrichment of 20-600 nm exosomes in just 30 minutes using Exodisc, achieving over 95% recovery from cell culture supernatant. However, microfluidic technology may not be suitable for large volume sample separation due to handling limitations[49]. Other techniques like chromatography, hydrostatic filtration dialysis, size-exclusion chromatography, lipid-based separation, and immunoaffinity-based methods may also facilitate exosome isolation. These methods allow for seamless integration with clinical diagnostics, thus broadening the potential clinical applications of exosomes[49]. Ongoing research and development continue to advance the field of exosome isolation, bringing us closer to unlocking the full potential of exosomes in clinical settings.

The accurate detection of extracted exosomes is a pivotal step in the research process. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles issued guidelines in 2018[65] that recommend three methods for identifying isolated EVs. First, one can examine membrane proteins or glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol-anchored protein surface markers. Second, one can scrutinize intracellular proteins (eukaryotic or Gram-positive) or periplasmic proteins (Gram-negative bacteria, eukaryotic, or Gram-positive bacteria). Third, one can consider non-EV-derived proteins, which may co-isolate with EVs, such as lipoproteins. However, it is crucial to interpret protein concentrations of isolated EVs with caution, as they can be frequently overestimated due to contamination. Furthermore, different EV subtypes can display diverse protein profiles[29]. The commonly used detection methods can be categorised into non-microscopic and microscopic methods, as detailed in Table 4.

| Detection method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

| Nanoparticle tracking analysis | Simple; can determine both particle size and concentration; can detect vesicles in the 10-1000 nm diameter range, covering the typical exosome size range of 50-150 nm | N/A | [66,67] |

| Dynamic light scattering | Provides information on relative particle size; can calculate absolute size distribution when microvesicle concentration is known; accurate for samples with exosomes of one specific size | Larger particles may hinder detection of smaller particles in samples with various particle sizes | [68-70] |

| Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay | A plate - based biochemical diagnostic tool for detecting and quantifying ligands, antibodies, and hormones; can assay exosomal membrane proteins and other marker proteins | Time - consuming (several hours to detect exosomes); requires a relatively large sample volume; low sensitivity for exosome detection | [71] |

| Colorimetric detection | User - friendly operation and straightforward signal readout for point-of-care testing; can be partitioned into AuNP-based assays (using AuNPs as signal transducers/amplifiers with high extinction coefficient and distance - dependent optical properties) and enzyme-H2O2-TMB-based assays (using enzymes to catalyze TMB solution for color signals) | Generally provides binary or semi-quantitative results | [72-74] |

| Fluorescent detection (including fluorescence spectrophotometry) | High sensitivity and excellent selectivity; can provide insights into exosome origins; can be divided into direct (specific recognition between exosome surface antigens and fluorescent - labeled aptamers or antibodies) and indirect (exosomes triggering fluorescence recovery) modes; can monitor exosome dynamics in real-time | N/A | [73,75-79] |

| Transmission electron microscopy | High imaging resolution (< 1 nm), well-suited for visualizing nanoparticles and assessing exosome morphology and heterogeneity | Fixation and dehydration steps in sample preparation may affect microvesicle morphology and size distribution | [71,80] |

| Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy | Eliminates potential effects on exosomes during sample preparation | N/A | [81] |

| Atomic force microscopy | Allows for sub-nanometer resolution imaging; can simultaneously measure exosome size distribution and map mechanical properties with nanometer accuracy; useful for quantifying and detecting exosome abundance, structure, biomechanics, etc. in tumor samples | N/A | [68,82-84] |

| Microfluidics (including integration with SPR technology and electrochemical detection) | Decreased reagent consumption, minimized contamination, reduced analysis times, increased throughput, and ease of integration and automation; enhanced exploration of exosome physicochemical and biochemical attributes at the microscale; can be integrated with SPR technology for multiparametric profiling of exosomes; electrochemical detection methods can be rapid and sensitive | Integration with SPR technology requires bulky, intricate instrumentation and is prone to severe interferences | [68,72,85-90] |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis: Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) is a technique that allows for the determination of both particle size and concentration. NTA software tracks individual vesicles as they exhibit Brownian motion, utilizing the Stokes-Einstein equation to associate this movement with particle size. In NTA, laser light is scattered as it interacts with particles in a chamber. A microscope with a mounted camera captures this scattered light. The camera records the particle movements in a video format, which the NTA software then processes to estimate the particle size and concentration[66]. NTA, among fluorescence methods, is widely utilized for characterizing exosome concentration and size due to its simplicity and ability to detect vesicles within the diameter range of 10-1000 nm, which encompasses the typical exosome size range of 50-150 nm[67].

Dynamic light scattering: In contrast, the dynamic light scattering technique provides information on a particle’s relative size compared to other particles in the suspension. Over time, it produces a relative size distribution of the particles in the suspension. Once the microvesicle concentration in the suspension is known, the absolute size distribution can be calculated based on the relative size distribution[68]. Dynamic light scattering is apt for samples containing exosomes of only one specific size, as it provides accurate size information[69]. However, in samples with a variety of particle sizes, larger particles may hinder the detection of smaller particles, limiting its suitability for obtaining size distribution in such cases[70].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a plate-based biochemical diagnostic tool used for detecting and quantifying ligands (like proteins), antibodies, and hormones present in a liquid sample. While ELISA has been utilized for assaying exosomal membrane proteins and other marker proteins, it comes with some limitations. Specifically, ELISA can be time-consuming, requiring several hours to detect exosomes, and it also demands a relatively large sample volume, which may not always be available. Additionally, ELISA exhibits low sensitivity when detecting exosomes. To overcome these challenges, researchers have leveraged the strengths of ELISA. For example, Liu et al[71] have developed an immunosorbent assay that involves mixing immunomagnetic beads with samples containing exosomes. This innovative approach allows for the quantification of cancer exosomes with high accuracy, overcoming the limitations of traditional ELISA.

Colorimetric detection: Colorimetric detection is a method that involves identifying a sample by comparing or measuring the color intensity of a chromogenic substance. When incorporated into microfluidics platforms for exosome detection, colorimetric assays become appealing for point-of-care testing due to their user-friendly operation and straightforward signal readout. Generally, colorimetry detects a sample by observing a color change, providing either a binary “yes/no” answer or a semi-quantitative result[72]. Colorimetric assays for exosome detection can be partitioned into two principal types based on the signal element used: AuNP-based assays and enzyme-H2O2-TMB (3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine)-based assays[73]. AuNPs are frequently employed as signal transducers/amplifiers in various biosensors owing to their high extinction coefficient and distance-dependent optical properties. They display distinct colors induced by variations in potential of hydrogenpotential of hydrogen (pH), salt concentration, aggregation level, or surface interactions.

Conversely, enzyme-H2O2-TMB-based colorimetric assays utilize natural enzymes or nanozymes to catalyze the TMB solution, subsequently generating color signals. For instance, Di et al[74] have described a nanozyme-assisted immunosorbent assay capable of sensitive and rapid profiling of exosomal proteins, such as CD63, carcinoembryonic antigen, glypican-3 (GPC-3), programmed death-ligand 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 from clinical samples. In this assay, the surface proteins of exosomes are specifically captured by antibodies immobilized on the surface of a microplate, which then catalyzes a colorimetric reaction, offering a means to detect and quantify the target exosomal proteins.

Fluorescent detection: Fluorescence is a valuable optical signal that can be harnessed to visualize particles, including exosomes. By utilizing appropriate fluorophores and specific interaction sites on the exosomes, efficient fluorescent assay methods can be constructed, which can provide valuable insights into exosome origins[75]. Fluorescent detection of exosomes can be divided into two main types. The first type involves specific recognition between exosome surface antigens and fluorescently labeled aptamers or antibodies, allowing for targeted detection and identification of exosomes based on their unique surface markers[76]. The second type relies on fluorescence recovery triggered by exosomes through the meticulous design of specific biomolecules and fluorescent materials, providing real-time, in-situ detection with the potential for multiple signal outputs[76]. Fluorescence-based methods offer several advantages, including high sensitivity and excellent selectivity, which enable accurate and reliable detection of exosomes. These techniques allow researchers to monitor exosome dynamics in real time, providing valuable insights into their biological functions and interactions[73].

Fluorescence spectrophotometry serves as a method for substance identification and content determination based on the presence and intensity of fluorescence spectral lines[77]. Fluorescence refers to a phenomenon wherein a material emits a photon when irradiated by light. The intensity, wavelength, and luminescence duration of the fluorescence are intimately tied to the properties of the material[75]. To construct a fluorescent assay method for exosomes, two core components are required: An efficient fluorophore and specific interaction sites on the exosomes. The fluorescent detection of exosomes can be categorized into two modes: Direct and indirect. The direct mode rests on the specific recognition between exosome surface antigens and fluorescent-labeled aptamers or antibodies[73]. Conversely, the indirect mode involves exosomes triggering fluorescence recovery via the meticulous design of specific biomolecules and fluorescent materials[76]. Li et al[78] have crafted a simple fluorescent aptasensor based on aggregation-induced emission luminogens (AIEgens). They employ a complex of graphene oxide absorbed with TPE-TAs (tetrafrylene containing tertiary amine) and an aptamer. In the absence of exosomes, this complex undergoes fluorescence quenching. However, upon the introduction of target exosomes, the aptamer preferentially binds to its target, leading to the detachment of the TPE-TAs/aptamer complex from the graphene oxide surface. This separation triggers a “turn-on” fluorescence signal, enabling the sensitive and specific detection of the target exosomes[79].

Transmission electron microscopy: Transmission electron microscopy provides an invaluable characterization method for assessing the morphology and heterogeneity of exosomes[71]. With high imaging resolution (< 1 nm), it is especially well-suited for visualizing nanoparticles, particularly those containing heavy elements (e.g., metals). However, it is important to note that the fixation and dehydration steps required for sample preparation can potentially affect the morphology and size distribution of the microvesicles. To address this issue, a microchip nano-pipet on a hydrophilic SixNy thin film has been developed using semiconductor processing. The small geometry of the nano-pipet enables puncturing sample droplets, effectively suppressing capillary flow during the vacuum drying process. This results in a more uniform distribution of nanoparticles on the platform after drying, facilitating electron microscopy imaging or other types of surface analyses[80]. Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy is another potent technique used for exosome detection that eliminates the potential effects on exosomes during sample preparation[81].

Atomic force microscopy: Atomic force microscopy (AFM) allows for sub-nanometer resolution imaging of substrates, particles, and molecules. This technique involves moving a mechanical cantilever across a sample surface, with piezoelectric sensors detecting minuscule variations in cantilever movement and converting them into a highly detailed profile of the measured sample surface[68]. AFM is capable of simultaneously measuring the size distribution of exosomes and mapping their mechanical properties with nanometer accuracy[82,83]. As a result, AFM proves to be a valuable tool for quantifying and detecting the abundance, structure, biomechanics, and other characteristics of exosomes in tumor samples[84].

Microfluidics: Traditional exosome detection technologies face hurdles due to the low levels of exosomal markers and the heterogeneity of exosome subpopulations, which restrict the sensitivity and selectivity of exosome detection. In contrast, microfluidic detection technologies offer unique advantages that render them ideal for the rapid and sensitive detection of exosomes[72,85]. The exploration of both the physicochemical and biochemical attributes of exosomes at the microscale has been substantially enhanced due to the significant strides in microfabrication technologies. Such advancements have unfolded valuable opportunities to design lab-on-a-chip microfluidic systems, thereby facilitating the efficient isolation of exosomes[68]. Microfluidic detection technologies, with their unique advantages over traditional methods, such as decreased reagent consumption, minimized contamination, reduced analysis times, increased throughput, and ease of integration and automation, render these systems particularly advantageous for the rapid, sensitive, and selective detection and analysis of exosomes[85,86].

Presently, the integration of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology into microfluidic platforms has become extensively utilized in exosome detection. For example, Wu et al[87] have devised a plasmonic platform tailored for multiparametric profiling of exosomes, enabling simultaneous biophysical and biomolecular evaluation of identical vesicles in clinical biological fluids. Despite these encouraging advancements, the application of microfluidics-based SPR techniques is somewhat constrained due to the necessity for bulky, intricate instrumentation and the potential for severe interferences[85].

A prominent example of electrochemical detection application is the work by Jeong et al[88], who have engineered an integrated magneto-electrochemical sensor for exosome analysis. The integrated magneto-electrochemical sensor platform operates through two primary steps: Magnetic selection and electrochemical detection. Initially, magnetic beads coated with antibodies against tetraspanin proteins (such as CD63, CD9, and CD81) are deployed for exosome capture and labeling. Subsequently, the captured exosomes are detected via electrochemical sensing. Remarkably, the entire assay is completed within an hour, requiring only 10 μL of the sample. This method proves advantageous for the diagnosis and monitoring of CRC[89].

Another significant contribution comes from Kashefi-Kheyrabadi et al[90], who have devised a detachable microfluidic device coupled with an aptamer-based electrochemical biosensing method, known as detachable microfluidic device implemented with electrochemical aptasensor (DeMEA). In DeMEA, an aptamer targeting epithelial cell adhesion molecule is immobilized on the electrode surface, which has been pre-electroplated with gold nanostructures. Microfluidic vortices are incorporated to enhance the collision chances between exosomes and the sensing surface. Consequently, DeMEA exhibits the ability to quantify exosomes from plasma samples of breast cancer patients at varying stages, thus providing highly sensitive and early detection of cancer-specific exosomes[90].

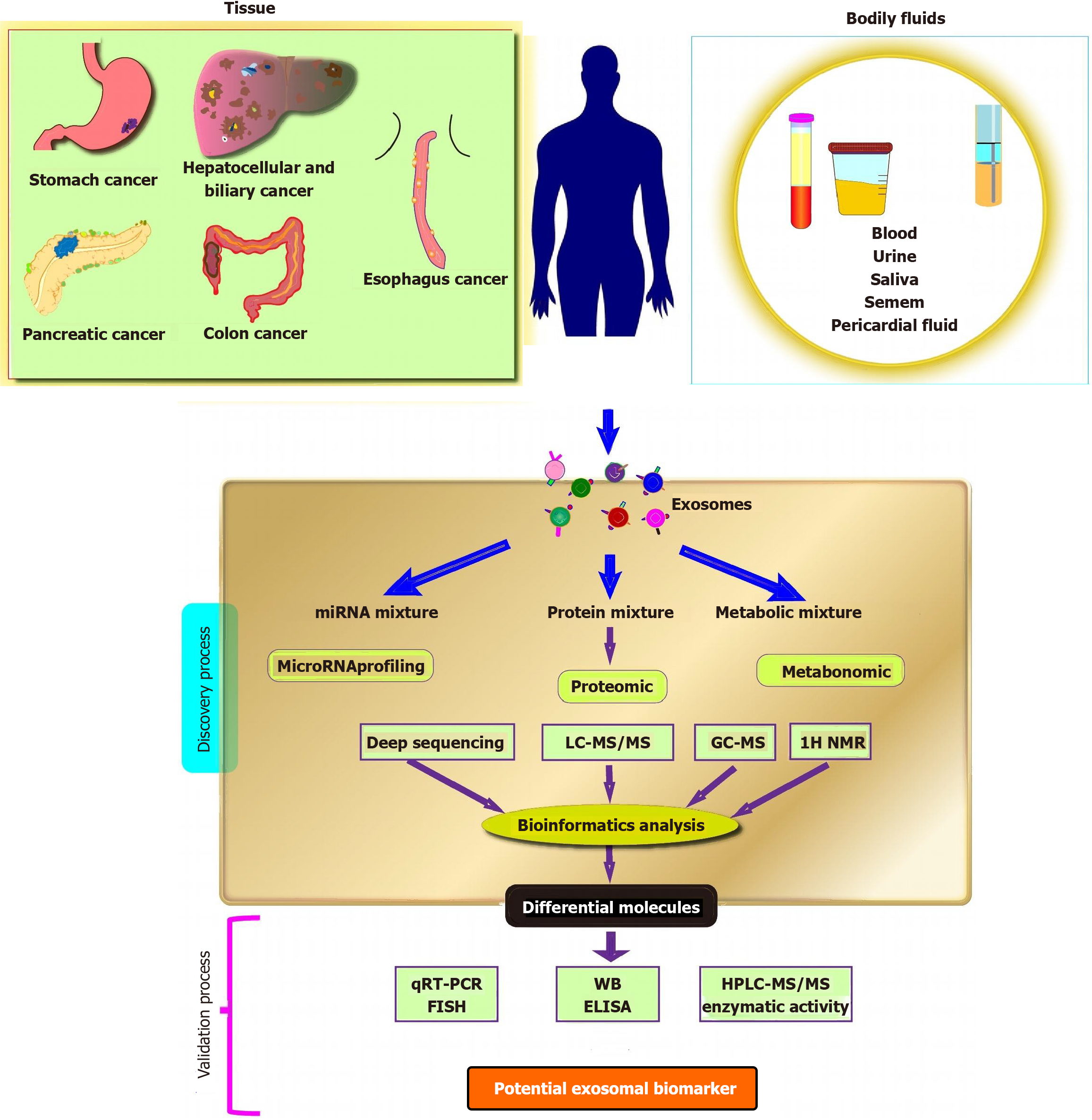

The unique advantages of exosomes render them a promising candidate for cancer diagnosis, particularly for the early detection of GI tumors (Figure 3). Firstly, variations in the composition and release of exosomes from cancer patients suggest that exosomes carry significant diagnostic value for tumors. These changes in exosomal content can function as reliable biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. Secondly, exosomes carry higher levels of specific molecular markers compared to apoptotic vesicles and microvesicles. This feature positions exosome as a less invasive, more sensitive, and cost-effective alternative for diagnosing GI tumors. Their elevated specificity enables more accurate and precise detection, leading to improved early diagnosis, which is critical for determining subsequent treatment strategies and advancing the development of personalized cancer therapies.

In patients with GI tumors, early diagnosis has emerged as a critical prognostic factor that significantly influences treatment outcomes. The detection of elevated levels of exosomes in the bodily fluids of cancer patients, as compared to healthy individuals, underscores their potential as valuable biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. These exosomes present distinct compositions, particularly with regard to miRNA, which can be indicative of tumorigenesis and progression. Furthermore, lncRNA, a type of ncRNA intimately linked to cancer development and progression, has demonstrated promise as a diagnostic marker when found in exosomes[91]. This highlights the potential of exosomal lncRNA as an additional valuable biomarker for cancer diagnosis (Table 5).

| GI cancer type | Exosome origin | Candidates’ biomarker | Clinical samples | Supporting evidence | Ref. |

| Colorectal cancer | Serum | Hsa-circ-0004771 | 179 patients; 45 healthy donors | AUC of 0.86, 0.88 to differentiate stage I/II CRC patients and CRC patients from healthy controls | [137] |

| Plasma | Epcam-CD63 | 59 cancer patients; 20 healthy donors | AUC of 0.96 | [138] | |

| Plasma | CD147 | AUC of 0.932, P < 0.001 | [139] | ||

| Serum | LncRNA UCA1+, circRNA HIPK3 | AUC of 0.900, P < 0.0001 | [140] | ||

| Plasma | miR-96-5p and miR-149 | 102 CRC patients | Significantly decreased in CRC tumor exosomes, and was significantly normalized after surgery | [98] | |

| Serum | miR-99b-5p and miR-150-5p | 169 CRC patients, 155 healthy donors, and 20 benign disease patients | The AUC of miR-99b-5p was 0.628 (32.1% sensitivity and 90.8% specificity), the AUC of miR-150-5p was 0.707 (75.2% sensitivity and 58.8% specificity) | [99] | |

| Plasma | miRNA-27a and miRNA-130a | 369 peripheral blood samples | The AUC of miR-27a (miR-130a) was 0.773 (0.742) in the training phase, 0.82 (0.787) in the validation phase | [100] | |

| Serum | miR-23a and miR-301a | 12 CRC patients and 8 healthy donors | AUC values for miR-23a and miR-301a were 0.900 and 0.840, respectively | [101] | |

| Plasma | Let-7b-3p, miR-139-3p, and miR-145-3p | 15 colon cancer patients and 10 healthy donors | Their combination (AUC = 0.927) showed an advantage in identifying CRC patients | [102] | |

| Serum | miR-126, miR-1290, miR-23a, and miR-940 | Showed high diagnostic values to differentiate CRC patients at TNM stage I from healthy controls | [103] | ||

| Esophageal cancer | Serum | miR-652-5p | 93 OSCC patients and 93 healthy individuals | AUC of 0.901 | [106] |

| Plasma | miR-93-5p | 83 ESCC patients and 83 healthy individuals | The expression level in the plasma of ESCC patients being 1.39 times higher than that of the control population (P = 0.035) | [107] | |

| Serum | miRNA-182 | 125 ESCC patients and 60 healthy individuals | AUC = 0.837, 95%CI: 0.776-0.887 | [108] | |

| Serum | UCA1, POU3F3, ESCCAL-1 and PEG10 | 313 ESCC patients and 313 control individuals without ESCC history | The AUC for UCA1, POU3F3, ESCCAL-1 and PEG10 were 0.733, 0.717, 0.676, 0.648, respectively | [109] | |

| Plasma | NR_039819, NR_036133, NR_003353, ENST00000442416.1, and ENST00000416100.1 | 295 ESCC patients, 43 esophagitis patients, and 49 healthy volunteers | The combined diagnostic value of these five lncRNAs revealed an AUC of 0.9995 (P < 0.001) | [110] | |

| CircRNA has-circ-0001946 and has-circ-0043603 | 3 pairs of ESCC frozen tumor and non-tumor tissues | The AUC, sensitivity and specificity of hsa_circ_0001946 was 0.894, 92.80%, of hsa_circ_0043603 was 0.836, 64.92% | [111] | ||

| Gastric cancer | Serum | Lnc HOTTIP | 126 GC patients; 120 healthy donors | AUC of 0.827 | [141] |

| Serum | miR-19b-3p and miR-106a-5p | 130 GC patients and 130 healthy donors | Levels of exosomes of patients with GC were markedly overexpressed compared to healthy donors | [114] | |

| Serum | miR10b-5p, miR132-3p, miR185-5p, miR195-5p, miR-20a3p, and miR296-5p | The training (49 gastric cancer vs 47 NCs) and validation phases (154 gastric cancer vs 120 NCs) | AUC were 0.764 and 0.702 for the training and validation phases, respectively | [115] | |

| Serum | miR-10a-5p, miR-19b-3p, miR-215-5p, and miR-18a-5p | A pair of 43 primary adenocarcinoma GC tissue samples with corresponding adjacent non-malignant counterparts | AUC of 0.801, 0.721, 0.780 and 0.736, respectively | [116] | |

| Serum | LncRNA PCSK2-2:1 | 29 healthy people and 63 gastric cancer patients | AUC of 0.896 | [117] | |

| Plasma | LncRNA SLC2A12-10:1 | 60 GC patients and 60 age-matched healthy controls | The area under the ROC curve was 0.776 | [118] | |

| Plasma | LncUEGC1 and lncUEGC2 | Five healthy individuals and ten stages I GC patients and from culture media of four human primary stomach epithelial cells and four GCCs | LncUEGC1 exhibited AUC values of 0.8760 and 0.8406 in discriminating EGC patients from healthy individuals | [119] | |

| Plasma | Hsa_circ_0065149 | Low expression levels in GC tissues were significantly associated with the tumor diameter (P = 0.034) and perineural invasion (P = 0.037) | [120] | ||

| Serum | CircSHKBP1 | 72 paired GC tissues and normal tissues | The expression of circSHKBP1 was 2.31-fold higher in GC tissues on average than in normal tissues | [121] | |

| Serum | miR-15b-3p | 108 GC patients; 108 healthy donors | AUC of 0.820; specificity of 80.6%; sensitivity of 74.1% | [142] | |

| Hepatocellular and biliary cancer | Plasma | AFP; GPC3; ALB; APOH; FABP1; FGB; FGG; AHSG; RBP4; TF mRNA | 36 HCC patients; 26 cirrhosis | AUC of 0.87; sensitivity of 93.8%; specificity of 74.5% | [143] |

| Serum | miR-21 | Higher in HCC patients | [144] | ||

| Serum | CEA; GPC-3, and PD-L1 | 12 HCC patients; 12 hepatitis B; 6 healthy donors | Higher in HCC patients | [74] | |

| Plasma | miRNA-122, miRNA-21, and miRNA-96 | 50 patients with HCC and 50 patients with hepatic cirrhosis and 50 healthy volunteers | AUC of 0.924; 95%CI; sensitivity 82%, specificity 92% to discriminating HCC from the cirrhosis group | [123] | |

| Serum | miR-10b-5p | 28 healthy individuals, 60 with chronic liver disease, and 90 with HCC | AUC of 0.934 | [124] | |

| Plasma | miR-21-5p and miR-92a-3p | 20 healthy individuals, 38 with liver cirrhosis, and 48 with HCC | MiR-21-5p was up-regulated and miR-92a-3p was down-regulated, and after incorporating AFP, the AUC was 0.85 | [125] | |

| Serum | miR-4661-5p | 15 normal subjects, 20 with CH, 10 with LC, 18 with HCC (Edmonson grade 1), and 45 with moderate to poorly differentiated HCC | AUC of 0.917 diagnose HCC in all stages, AUC of 0.923 in early stage | [126] | |

| Plasma | RN7SL1, SNHG1, ZFAS1, and LINC01359 | 57 plasma cell-free RNA transcriptome and 20 exosomal RNA transcriptomes | RN7SL1 discriminated HCC samples from negative controls (AUC = 0.87; 95%CI: 0.817-0.920) | [127] | |

| Plasma | miR-96-5p, miR-151a-5p, miR-191-5p, and miR-4732-3p | 5 CCA patients and 4 GBC patients before and after surgery, 40 healthy individuals, 45 more CCA patients and 24 more GBC patients to validate | AUC of 0.733, 0.7639, 0.5417, and 0.6544, respectively | [128] | |

| Pancreatic cancer | Plasma | miRNA-10b | 3 PDAC patients; 3 CP patients; 3 healthy donors | Higher in PDAC patients | [145] |

| Plasma | miRNA-10b | PDAC patients; CP patients and healthy donors | Higher in PDAC patients | [146] | |

| Mouse plasma samples | miR-3970-5p | 9 healthy donors; 9 pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia patients; 9 PDAC patients | Accuracy of 65% | [147] | |

| Serum | EpCAM, Glypican1 | 90% accuracy for pancreatic cancer or normal pancreatic epithelial cell lines; 87 and 90% predictive accuracy for healthy control and EPC individual samples | [148] | ||

| Plasma | miR-4525, miR-451a and miR-21 | 55 patients with PDAC and 20 healthy volunteers | The exosomal levels from PDAC patients were significantly higher than those from healthy volunteers | [130] | |

| Serum | miR-1246, miR-4306, and miR-4644 | 131 pancreatic cancer patients and 89 controls | Significantly increased in 83% of pancreatic cancer patients compared to healthy controls, P < 0.05 | [131] | |

| Plasma | LINC01268, LINC02802, AC124854.1, AL132657.1 | 78 pancreatic cancer patients and 70 healthy controls | The ROC analysis revealed AUC values of 0.8421, 0.6544, 0.7190, and 0.6231 for LINC01268, LINC02802, AC124854.1, and AL132657.1, respectively | [132] | |

| Plasma | Long-stranded RNAs (FGA, KRT19, HIST1H2BK, ITIH2, MARCH2, CLDN1, MAL2 and TIMP1) | Samples from 284 patients with PDAC, 100 patients with chronic pancreatitis and 117 healthy controls | Diagnosed PDAC with 0.949 AUC to identify stage I/II tumors | [133] | |

| Serum | Small nucleolar RNAs: WASF2, ARF6, SNORA74A, and SNORA25 | 27 pancreatic cancer patients and 13 controls | The AUCs of WASF2, ARF6, SNORA74A, and SNORA25 in serum from patients in the early stages of pancreatic cancer (stages 0, I, and IIA) were > 0.9 | [134] | |

| Serum | Glypican1 | 190 pancreatic cancer patients and 131 controls | Sensitivity of 100%; specificity of 100%; positive predictive value of 100%; negative predictive value of 100%; AUC of 1.0 | [135] |

CRC is globally recognized as the third most common human malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality[92-94]. This high mortality rate can be largely attributed to delayed diagnoses and treatment, with more than half of CRC patients not surviving[95]. In order to tackle this challenge, exosomal miRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers for CRC diagnosis due to their ubiquitous presence and high specificity to CRC[96].

The researchers identified 660 mature miRNAs in CRC patients at different stages of the disease, of which 29 miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed compared to healthy controls[97]. These miRNAs were either highly upregulated (e.g., let-7a-5p, let-7c-5p, let-7f-5p, let-7d-3p, miR-423-5p, miR-3184-5p, and miR-584) or down-regulated (e.g., miR-30a-5p, miR-99-5p, miR-150-5p, miR-26-5p, and miR-204-5p). Research conducted by Li et al[98] has demonstrated that miR-96-5p and miR-149 expressions in tumor tissues, plasma of CRC patients, and GPC1 exosomes from CRC patients are significantly lower compared to those in peritumoral tissues and plasma of healthy individuals. The overexpression of these miRNAs markedly increases cell apoptosis and reduces both cell proliferation and GPC1 expression in CRC cell lines, plasma from mice bearing CRC cell line tumors, and xenograft tumors. Additionally, the analysis of RNA sequence data reveals a significant downregulation of exosomal miR-99b-5p and miR-150-5p levels in early-stage CRC patients compared to healthy individuals[99]. Moreover, plasma samples from CRC patients displayed significant levels of exosomal miRNA-27a and miRNA-130a[100]. Another study has substantiated the overexpression of exosomal miRNA-23a and further reinforced the diagnostic value of exosomal miRNA-301a, yielding area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values of 0.900 and 0.840, respectively[101].

Min et al[102] have found that three miRNAs (let-7b-3p, miR-139-3p, and miR-145-3p) are prominently enriched in plasma exosomes. In combination, these miRNAs provide a significant advantage in identifying CRC patients, demonstrating an AUC of 0.927. Concurrently, Shi et al[103] have identified four exosomal miRNAs (miR-126, miR-1290, miR-23a, and miR-940) in the serum of CRC patients that can effectively differentiate CRC patients at tumor, lymph node, metastasis stage I from healthy individuals, thereby endorsing these exosomal miRNAs as promising diagnostic biomarkers in CRC.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a notably aggressive malignancy, frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, underlining the urgency for early diagnosis[104]. Researchers have investigated the potential of exosomal miRNAs and circRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for ESCC[105]. Gao et al[106] have detected a significant decrease in exosomal miR-652-5p in ESCC patients compared to healthy controls, proposing circulating miR-652-5p as a potential novel biomarker for ESCC diagnosis. In a similar vein, Liu et al[107] have discovered that miR-93-5p can be transported between esophageal cancer cells via exosomes, potentially promoting the proliferation of esophageal squamous carcinoma cells through the phosphatase and tensin homolog/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway by suppressing the expression of p21 and cyclin D1.

Qiu et al[108] have compared the expression levels of miRNA-182 in serum exosomes of ESCC patients and healthy individuals, achieving an AUC of 0.837. This suggests that serum exosomal miRNA-182 can serve as a potential diagnostic marker for ESCC. Yan et al[109] have demonstrated that circulating exosomal urothelial carcinoma associated 1, POU3F3, ESCC-associated lncRNA-1, and paternal expressed gene 10 can potentially contribute to diagnosing ESCC, presenting AUC values ranging from 0.648 to 0.733. Jiao et al[110] have observed significantly higher levels of plasma exosomes NR-039819, NR-036133, NR-003353, ENST00000442416.1, and ENST00000416100.1 in ESCC patients compared to patients with esophagitis and healthy controls. Lastly, Fan et al[111] have confirmed circRNAs hsa-circ-0001946 and hsa-circ-0043603, secreted by ESCC cells, as potential diagnostic biomarkers for ESCC. These circRNAs present AUC values of 0.894 and 0.836, respectively, when used independently. When combined, the circRNAs yield an even higher AUC value of 0.928. Despite these promising findings, more studies are needed to validate the validity and reliability of exosome analysis as a diagnostic tool for ESCC. Further research will contribute to enhancing the understanding of exosomal biomarkers and their potential clinical utility in early ESCC detection.

According to the Global Cancer Observatory, CANCER TODAY (GLOBOCAN) 2018 statistics, gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common human malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related death[92]. Regrettably, many GC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, underscoring the necessity for simple, innovative, and effective biomarkers for early detection[112]. Current clinical diagnostic biomarkers for GC, such as carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), exhibit limitations in sensitivity and specificity, making the development of improved diagnostic tools for GC a pressing need[113].

Numerous studies have thus focused on the significance of circulating exosomal miRNAs as potential tumor diagnostic markers. For instance, Wang et al[114] have compared the serum of GC patients and healthy controls, finding significantly increased levels of miR-19b-3p and miR-106a-5p in the exosomes of GC patients compared to those of healthy subjects. The combined use of these two miRNAs enhances diagnostic accuracy compared to using either individually, outperforming tumor markers alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and CA19-9. However, the study does not investigate the potential of these miRNAs for early GC detection. In another study by Huang et al[115], the researchers have explored the differential expression profile of serum miRNAs in GC patients. They have detected elevated levels of miR10b-5p, miR132-3p, miR185-5p, miR195-5p, miR20a-3p, and miR296-5p in the serum exosomes of GC patients compared to healthy controls. This discovery suggests a potential role for circulating exosomal miRNAs in GC detection. In addition, they have identified an onco-miRNA panel comprising exosomal miR-10a-5p, miR-19b-3p, miR-215-5p, and miR-18a-5p as potential biomarkers for GC[116].

In addition to miRNAs, lncRNAs have also surfaced as potential diagnostic biomarkers for GC. Cai et al[117] have observed that the exosomal expression of lncRNA PCSK2-2:1 in GC patients is notably lower than in the control group. This lncRNA shows a correlation with venous invasion, tumor stage, and tumor size, indicating its potential as a diagnostic biomarker for GC[117]. Another study has proposed that the diagnostic value of exosomal lncRNA SLC2A12-10:1 in distinguishing GC patients from healthy subjects exceeds that of traditional tumor biomarkers[118]. This emphasizes the promising potential of exosomal lncRNAs as diagnostic tools for GC. Moreover, few studies have specifically evaluated exosomal biomarkers for differentiating GC from other non-malignant stomach conditions, such as chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Lin et al[119] have assessed patients with stage I and II GC and discovered that levels of exosomal lncUEGC1 and lncUEGC2 are significantly elevated in early-stage GC (P < 0.0001). Additionally, the expression of plasma exosomal lncUEGC1 is significantly increased in stage 1 GC patients compared to chronic atrophic gastritis patients. These findings propose the potential utility of exosomal lncRNAs as novel tumor markers for GC screening and for distinguishing GC from non-malignant conditions.

Recently, circRNAs have gained significant interest in the field of tumor research, especially regarding their potential value in tumor diagnosis. Several studies have reported notable findings relating to exosomal circRNAs and their association with GC diagnosis. One study has disclosed a marked decrease in exosomal hsa-circ-0065149 Levels in early GC patients compared to a healthy cohort, suggesting the potential of this circRNA as a diagnostic biomarker for early-stage GC[120]. Similarly, Xie et al[121] have observed an increased expression of circSHKBP1 in the serum of GC patients relative to healthy controls. Moreover, a sub-analysis exhibits a decrease in circSHKBP1 expression following tumor removal in 12 patients, supporting the potential application of circSHKBP1 as a diagnostic biomarker for GC. These findings underscore the potential of exosomal circRNAs as promising biomarkers, offering enhanced precision in GC detection compared to traditional biomarkers. The utilization of exosomal biomarkers in tumor research holds significant promise in improving early diagnosis and offering valuable insights into the detection and management of GC. However, further research and validation studies are required to fully establish the clinical utility and reliability of exosomal circRNAs as diagnostic tools for GC.

Liver cancer, specifically hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), is a significant health concern, ranking as the seventh most common human malignancy and the second most lethal[122]. The early diagnosis of HCC is crucial given its propensity to invade blood vessels and form distant metastases early on, which contributes to a poor patient prognosis. Research has yielded promising results regarding the use of exosomal miRNAs as potential biomarkers for HCC diagnosis. For instance, exosomal miRNA-122, miRNA-21, and miRNA-96 display high accuracy in distinguishing HCC from cirrhosis patients and healthy volunteers, with an AUC of 0.924, sensitivity of 82%, and specificity of 92%[123].

Serum exosomal miR-10b-5p, found to be upregulated in HCC patients, can effectively differentiate HCC patients from healthy controls with an AUC of 0.934[124]. Exosomal miR-21-5p has been found to be upregulated, while miR-92a-3p is downregulated in HCC patient exosomes. Incorporating these exosomal miRNAs with AFP significantly enhances HCC diagnosis compared to using AFP alone, with an AUC of 0.85[125]. An integrative analysis of miRNA expression profiles across various datasets reveals that serum exo-miR-4661-5p can diagnose HCC at all stages with an AUC of 0.917 and shows even higher accuracy in early-stage HCC with an AUC of 0.923. This outperformed other candidate exo-miRs and serum AFP[126].

In addition to miRNAs, other ncRNAs have also shown potential as diagnostic biomarkers for HCC. For instance, 16 ncRNAs are significantly upregulated in plasma from HCC patients. Specifically, the abundance of RN7SL1 fragment can effectively distinguish HCC samples from negative controls with an AUC of 0.87[127]. It has been demonstrated that levels of miR-96-5p, miR-151a-5p, miR-191-5p, and miR-4732-3p are significantly elevated in the exosomes of cholangiocarcinoma patients. Meanwhile, miR-151a-5p levels show a slight increase in the exosomes of gallbladder cancer patients[128]. These discoveries suggest that the specific altered expression of these miRNAs within patient exosomes can potentially serve as bio-diagnostic markers, enabling the differentiation of these cancer patients from healthy individuals.

Pancreatic cancer is a highly aggressive and metastatic type of tumor, notorious for its poor prognosis. Given its rapid progression and non-specific symptoms, early detection is of paramount importance to enhance patient survival rates. Recently, exosomes have emerged as potential assets for the early detection and diagnosis of pancreatic cancer[129]. In their investigation, Kawamura et al[130] have analyzed exosomes present in the plasma of portal venous blood and peripheral blood derived from 55 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), along with 20 healthy volunteers. Their findings reveal that exosomal levels of miR-4525, miR-451a, and miR-21 in portal venous blood are significantly higher in PDAC patients in comparison to peripheral blood. These specific miRNAs can potentially act as valuable biomarkers for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and for predicting postoperative recurrence. In a separate study by Madhavan et al[131], the researchers have compared the levels of serum exosomal miRNAs in pancreatic cancer patients to those of healthy controls and patients suffering from non-malignant diseases. They discover that the levels of miR-1246, miR-4306, and miR-4644 are significantly increased in 83% of pancreatic cancer patients relative to the control groups. These findings suggest that these specific exosomal miRNAs may hold diagnostic potential in the clinical management of pancreatic cancer. Moreover, in a study carried out by He et al[132], scrutinized investigates the role of lncRNAs in pancreatic cancer. It identifies four plasma-derived exosomal lncRNAs (LINC01268, LINC02802, AC124854.1, and AL132657.1) that are highly expressed in pancreatic cancer patients compared to healthy controls. These lncRNAs demonstrate significant diagnostic potential, with higher sensitivity and specificity than the conventional biomarker CA19-9.

Yu et al[133] have conducted an RNA-seq analysis of exosomes derived from the plasma samples of 284 patients with PDAC, 100 patients with chronic pancreatitis, and 117 healthy individuals. They have identified eight long-strand RNAs, such as fibrinogen alpha chain, keratin 19, histone cluster 1 H2B family member K, inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain 2, membrane associated ring-CH-type finger 2, claudin 1, Mal T-cell differentiation protein 2, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1, that demonstrate remarkable diagnostic capabilities for PDAC, including a notable AUC of 0.949 for the identification of stage I/II tumors. These exosomal markers also surpass the conventional biomarker CA19-9 in distinguishing PDAC from chronic pancreatitis (with respective AUCs of 0.931 and 0.873).

In another study, Kitagawa et al[134] have assessed a panel of exosomal mRNA and small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) against CA19-9 for their efficiency in distinguishing pancreatic cancer patients from healthy individuals. The researchers have found that the expressions of WAS protein family member 2, ADP ribosylation factor 6, snoRNA H/ACA Box 74A, and snoRNA H/ACA box 25 all exhibit receiver operating characteristic curve values exceeding 0.90. This suggests their potential as robust biomarkers for pancreatic cancer, compared to CA19-9. Notably, WAS protein family member 2 demonstrates a stronger correlation with pancreatic cancer risk.

Melo et al[135] have made a significant discovery that glypican-1+ circulating exosomes (GPC-1+ crExos) display a high degree of specificity and sensitivity for identifying PDAC patients compared to both healthy individuals and those with chronic pancreatitis. The AUC for GPC-1+ crExos is an impressive 1.0, significantly outperforming CA19-9, which has an AUC of 0.739. Furthermore, the combined use of GPC-1 and CD63 exhibits an excellent discriminatory ability, achieving 99% sensitivity and 82% specificity in differentiating PDAC patients from healthy subjects[136].

Despite the plethora of scientific evidence highlighting the potential benefits of exosomal biomarkers in cancer care, challenges and difficulties in their clinical applications persist on multiple fronts (Table 6). Firstly, the techniques for the extraction and isolation of exosomes are not yet widespread and are subject to limitations. Different isolation methods may yield distinct subpopulations of EVs, characterized by variations in miRNAs, proteins, diameters, and functions. Such disparities can significantly impact the accuracy of exosome-based diagnoses, making the purity of exosomes a primary concern. Secondly, the development of standardized operating procedures and data-handling methods is imperative. Current clinical guidelines for liquid biopsy lack uniform and robust evidence, resulting in various studies proposing the use of exosomes as biomarkers employing different purification methods. This leads to substantial heterogeneity in vesicles, complicating comparative studies and compromising the uniformity of assay quality. Additionally, the utilization of different techniques or assays to detect markers may result in variations in sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, the use of exosomes as biomarkers requires considerable effort to address all potential sources of variation. Thirdly, validation through large-scale clinical studies is a crucial aspect of the clinical application of exosomes. Presently, the sample sizes in relevant studies are insufficient, the data are too limited, and the validation periods are often too short of drawing definitive conclusions. Moreover, most studies tend to concentrate solely on the specificity and sensitivity of exosome detection systems, neglecting other vital aspects such as consistency, reproducibility, accuracy, reference ranges, and minimum detection limits required for comprehensive testing. Consequently, further research is imperative to substantiate the exosomal markers of tumors and, thereby, offer valuable clinical guidance.

| Limitation aspect | Details |

| Extraction and isolation | Techniques are not widespread and have limitations. Different isolation methods produce distinct EV subpopulations with variations in miRNAs, proteins, diameters, and functions. Purity of exosomes is a major concern as it impacts diagnostic accuracy |

| Standardization | Lack of standardized operating procedures and data - handling methods. Current liquid biopsy clinical guidelines lack uniform and robust evidence. Variations in sensitivity and specificity occur due to different detection techniques/assays |

| Large scale clinical validation | Sample sizes in relevant studies are insufficient, data are limited, and validation periods are often too short to draw definitive conclusions. Most studies focus only on specificity and sensitivity of exosome detection systems, neglecting other crucial aspects like consistency, reproducibility, accuracy, reference ranges, and minimum detection limits |

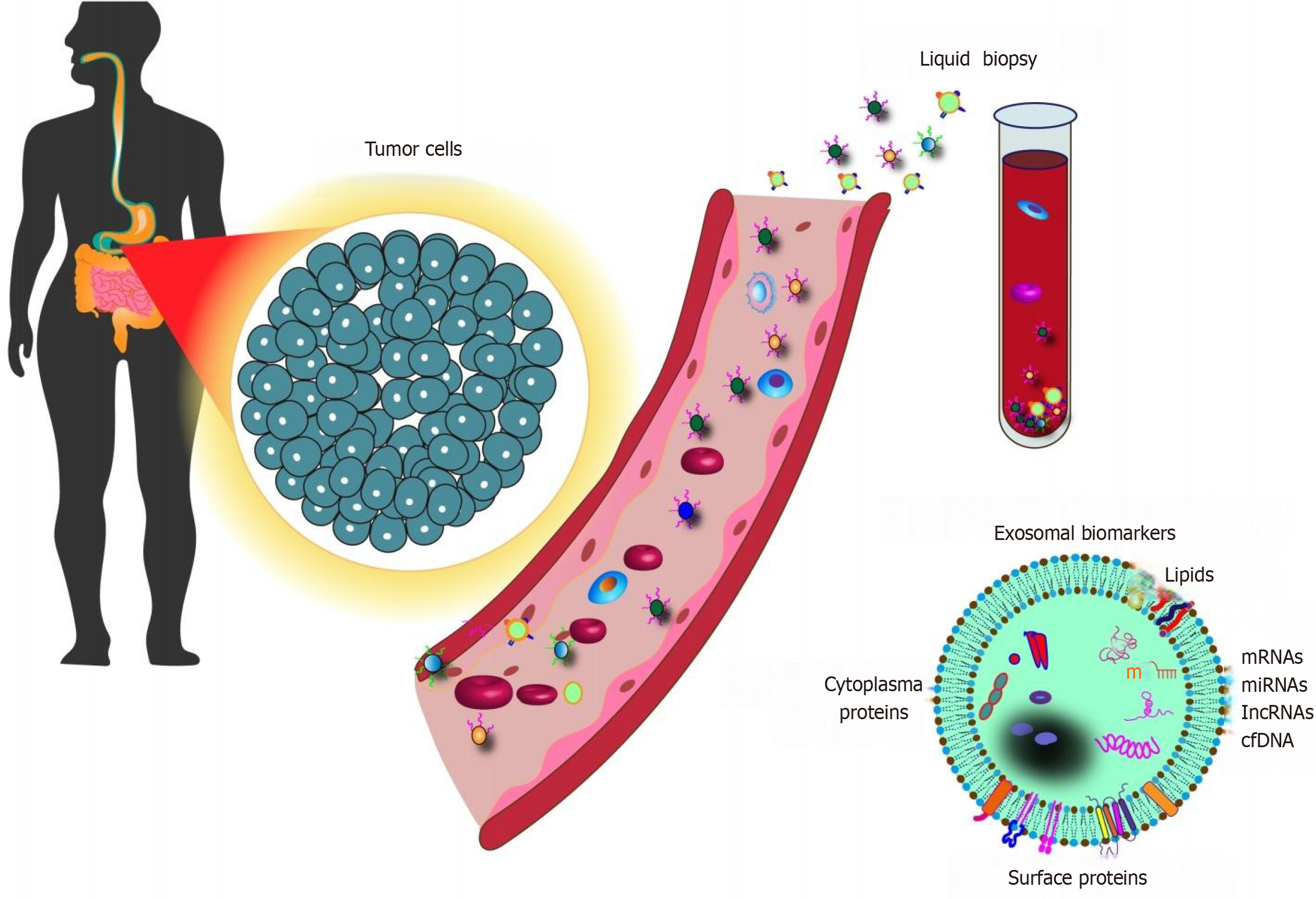

The dearth of effective and practical biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis contributes significantly to the dismal survival rates of cancer patients. However, advancements in our understanding of exosome biology have revolutionized our knowledge of the critical steps in cancer development. Exosomes, as emerging tumor markers, offer several unique advantages. Firstly, exosomes consist of a lipid bilayer membrane, providing stability and safeguarding their cargo-DNA, mRNA, miRNA, and proteins-from degradation during circulation throughout the body. Secondly, their non-invasive extraction and presence in various body fluids make them highly accessible for diagnostic purposes. Thirdly, they experience minimal interference from serum components and carry a diverse assortment of bioactive molecules. Finally, exosomes may display superior sensitivity and specificity compared to some traditional diagnostic methods (Figure 4).

In summary, exosomes emerge as an appealing and promising class of novel tumor markers. Their potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers have been exhaustively explored across various types of cancers. However, the practical application of exosome-based liquid biopsy for precision cancer medicine encounters substantial technical challenges. The high heterogeneity and nanoscale size of exosomes can hinder the retrieval of their molecular information and insights into their interactions. To surmount these hurdles, it is crucial to bolster the development of innovative strategies for optimizing exosome collection and profiling their contents rapidly and sensitively. In conclusion, despite the challenges faced in implementing exosome-based diagnostics, it is essential to convert these obstacles into tangible clinical applications for the betterment of patient outcomes in the near future.

| 1. | Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:335-349.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 857] [Cited by in RCA: 1211] [Article Influence: 242.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Crosby D, Bhatia S, Brindle KM, Coussens LM, Dive C, Emberton M, Esener S, Fitzgerald RC, Gambhir SS, Kuhn P, Rebbeck TR, Balasubramanian S. Early detection of cancer. Science. 2022;375:eaay9040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 164.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lima LG, Ham S, Shin H, Chai EPZ, Lek ESH, Lobb RJ, Müller AF, Mathivanan S, Yeo B, Choi Y, Parker BS, Möller A. Tumor microenvironmental cytokines bound to cancer exosomes determine uptake by cytokine receptor-expressing cells and biodistribution. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jo H, Shim K, Jeoung D. Exosomes: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications in Cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Doyle LM, Wang MZ. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells. 2019;8:727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1394] [Cited by in RCA: 2106] [Article Influence: 351.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 6. | Li M, Li S, Du C, Zhang Y, Li Y, Chu L, Han X, Galons H, Zhang Y, Sun H, Yu P. Exosomes from different cells: Characteristics, modifications, and therapeutic applications. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;207:112784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Qi Y, Xu R, Song C, Hao M, Gao Y, Xin M, Liu Q, Chen H, Wu X, Sun R, Zhang Y, He D, Dai Y, Kong C, Ning S, Guo Q, Zhang G, Wang P. A comprehensive database of exosome molecular biomarkers and disease-gene associations. Sci Data. 2024;11:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, Li S, Guo W, Zhao J, Chen D, Gu J, He X, Huang S. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015;25:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1303] [Cited by in RCA: 1742] [Article Influence: 174.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yi Q, Yue J, Liu Y, Shi H, Sun W, Feng J, Sun W. Recent advances of exosomal circRNAs in cancer and their potential clinical applications. J Transl Med. 2023;21:516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jella KK, Nasti TH, Li Z, Malla SR, Buchwald ZS, Khan MK. Exosomes, Their Biogenesis and Role in Inter-Cellular Communication, Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Immunotherapy. Vaccines (Basel). 2018;6:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dai J, Su Y, Zhong S, Cong L, Liu B, Yang J, Tao Y, He Z, Chen C, Jiang Y. Exosomes: key players in cancer and potential therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 155.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang Y, Bi J, Huang J, Tang Y, Du S, Li P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:6917-6934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 566] [Cited by in RCA: 815] [Article Influence: 163.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xiao Y, Zhong J, Zhong B, Huang J, Jiang L, Jiang Y, Yuan J, Sun J, Dai L, Yang C, Li Z, Wang J, Zhong T. Exosomes as potential sources of biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;476:13-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vahabi A, Rezaie J, Hassanpour M, Panahi Y, Nemati M, Rasmi Y, Nemati M. Tumor Cells-derived exosomal CircRNAs: Novel cancer drivers, molecular mechanisms, and clinical opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;200:115038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Simons M, Raposo G. Exosomes--vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1601] [Cited by in RCA: 1786] [Article Influence: 111.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tang XH, Guo T, Gao XY, Wu XL, Xing XF, Ji JF, Li ZY. Exosome-derived noncoding RNAs in gastric cancer: functions and clinical applications. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Scavo MP, Depalo N, Tutino V, De Nunzio V, Ingrosso C, Rizzi F, Notarnicola M, Curri ML, Giannelli G. Exosomes for Diagnosis and Therapy in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee YJ, Shin KJ, Chae YC. Regulation of cargo selection in exosome biogenesis and its biomedical applications in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56:877-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O'Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3959] [Cited by in RCA: 4095] [Article Influence: 409.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Andreu Z, Yáñez-Mó M. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front Immunol. 2014;5:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 697] [Cited by in RCA: 1030] [Article Influence: 93.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kastelowitz N, Yin H. Exosomes and microvesicles: identification and targeting by particle size and lipid chemical probes. Chembiochem. 2014;15:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kowal J, Tkach M, Théry C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;29:116-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 1374] [Article Influence: 124.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |