Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.102085

Revised: February 5, 2025

Accepted: February 24, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 8.8 Hours

Gastric schwannoma (GS) is often misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal stromal tumors due to the high incidence of the latter. However, these two types differ significantly in pathology and biological behavior.

To evaluate the computed tomography characteristics of GS and provide insights into its accurate diagnosis.

Twenty-three cases of GS confirmed between January 2011 and December 2023 were assessed clinically and radiologically. Imaging characteristics, including tumor location, size, contour, ulceration, growth pattern, enhancement degree and pattern, cystic change, calcification, and perigastric lymph nodes (PLNs), were reviewed by two experienced radiologists.

Our sample included 18 females and 5 males, with a median age of 54.7 years. A total of 39.1% of cases were asymptomatic. GSs appeared as oval and well-defined submucosal tumors, with exophytic (43.5%) or mixed (endoluminal + exophytic; 43.5%) growth patterns. The tumors were primarily located in the gastric body (78.3%). Ulcerations were observed in 8 cases (34.5%), and PLNs were observed in 15 cases (65%). The average degree of enhancement was 48.3 Hounsfield units. Twenty cases (87%) showed peak enhancement in the delayed phase. Most GSs were ho

GS predominantly showed gradual homogenous enhancement with peak enhancement in the delayed phase. PLNs around GS are helpful in differentiating GS from other gastric submucosal tumors.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective dual-center observational study analyzing the imaging characteristics of gastric schwannoma (GS) and their correlation with Ki-67 expression. GS predominantly occurs in middle-aged women and appears as an oval, well-defined, hypodense submucosal mass with progressive, homogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Enlarged perigastric lymph nodes, confirmed as reactive hyperplasia, are a key distinguishing feature from gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ki-67 expression remains low, indicating minimal proliferative activity. Although GS is benign, accurate preoperative differentiation from other submucosal tumors is crucial for appropriate management.

- Citation: Mo YK, Chen XP, Hong LL, Hu YR, Lin DY, Xie LC, Dai ZZ. Gastric schwannoma: Computed tomography and perigastric lymph node characteristics. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 102085

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/102085.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.102085

Schwannomas are neoplasms originating from Schwann cells within nerve sheaths. They behave as World Health Organization grade I tumors and rarely undergo malignant transformation[1]. They can occur in various parts of the body, including the head and neck, spinal cord, and limbs[2], but are infrequently found in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastric schwannoma (GS) was first reported in 1988 by Daimaru et al[3], who described 24 cases of gastrointestinal schwannoma, 23 of which were located in the stomach. Subsequent studies have confirmed that gastrointestinal sch

GS is often misdiagnosed as GIST owing to its high incidence. However, these two tumor types differ significantly in pathology and biological behavior for example, GS is benign, whereas GIST has malignant potential[7] and thus requires distinct treatment strategies[4,8,9]. Careful preoperative evaluation and accurate diagnosis are essential for guiding effective treatment. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is recommended by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy as the most effective tool for characterizing submucosal lesions. However, EUS alone is insufficient to distinguish between different types of gastric submucosal tumors[10]. Additionally, its limited penetration depth restricts the assessment of surrounding structures, especially regarding lymph node involvement. Computed tomography (CT), a noninvasive imaging technique widely used in abdominal diseases, including gastric masses, offers high spatial resolution and rapid scanning, reducing physiological motion artifacts. CT assists in tumor localization and evaluation of infiltration signs, perigastric lymph nodes (PLNs) enlargement, and abdominal metastases. To enhance diagnostic accuracy for GS, in this study, we examined 23 cases and explored the relationship between its imaging features and a proliferation marker, Ki-67.

We retrospectively investigated 34 patients with pathologically confirmed GS between January 2011 and June 2023 at two hospitals in Shantou, Guangdong Province. Of these, 23 cases (14 from one institution and nine from the other) had available CT images from plain scans and triple-phase dynamic contrast scans. The images were of good quality and met the diagnostic criteria for GS.

Nine cases were scanned using a Siemens multidetector spiral CT (SOMATOM Definition Flash; Siemens Healthcare, Germany), while 14 cases were assessed using a multidetector spiral CT scanner from GE HealthCare (Discovery 750HD, GE HealthCare or LightSpeed VCT, GE Healthcare). Images were acquired using a 120 kV and 200 mA protocol with a slice thickness of 0.625 mm. All patients underwent non-contrast plain scans and triple-phase dynamic contrast scans, including the arterial, portal, and delayed phases. Delay times for contrast-enhanced CT scans were 30 seconds for the arterial phase, 60 seconds for the portal phase, and 120 seconds for the delayed phase following intravenous administration of a nonionic contrast agent (Iopromide, Ultravist; Schering, Berlin, Germany) at a rate of 3 mL/second. To ensure optimal gastric distension, all patients fasted for at least 8 hours and consumed 500-1000 mL of water prior to the examination to enhance visualization of the gastric wall.

Image data were reviewed in a stack mode on a picture archiving and communication system by two experienced abdominal radiologists, each with 10 years of experience. The radiologists evaluated the images through consensus. The imaging features of GS were assessed in the following aspects: Location, size (maximum diameter), contour (oval or lobulated), growth pattern (endoluminal, exophytic, or mixed), degree and pattern of enhancement (homogeneous or heterogeneous), ulceration (mucosal defect on the tumor surface), cystic change (low-attenuation area in the lesion without enhancement), calcification, and enlarged PLNs (defined as a short-axis diameter ≥ 5 mm)[11,12].

CT values [in Hounsfield units (HU)] for the plain phase, arterial phase, portal phase, and delayed phase were measured, avoiding necrotic or cystic areas. Each radiologist conducted one measurement, and the results were averaged. The degree of enhancement was defined as the peak CT value after contrast enhancement minus the CT value of the plain phase.

All tumors and PLNs were surgically removed. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Archival hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides from all cases were examined by board-certified pathologists. Immunohistochemical staining was performed for the schwannoma-specific marker S-100 protein and the GIST markers cluster of differentiation 117 (CD117) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) in all 23 cases. The cell proliferation marker Ki-67 was tested in 22 cases.

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical product and service solutions software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Spearman correlation was performed to assess the relationship between imaging features (size, cystic change, calcification, ulceration, and PLNs) and the Ki-67 index. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed).

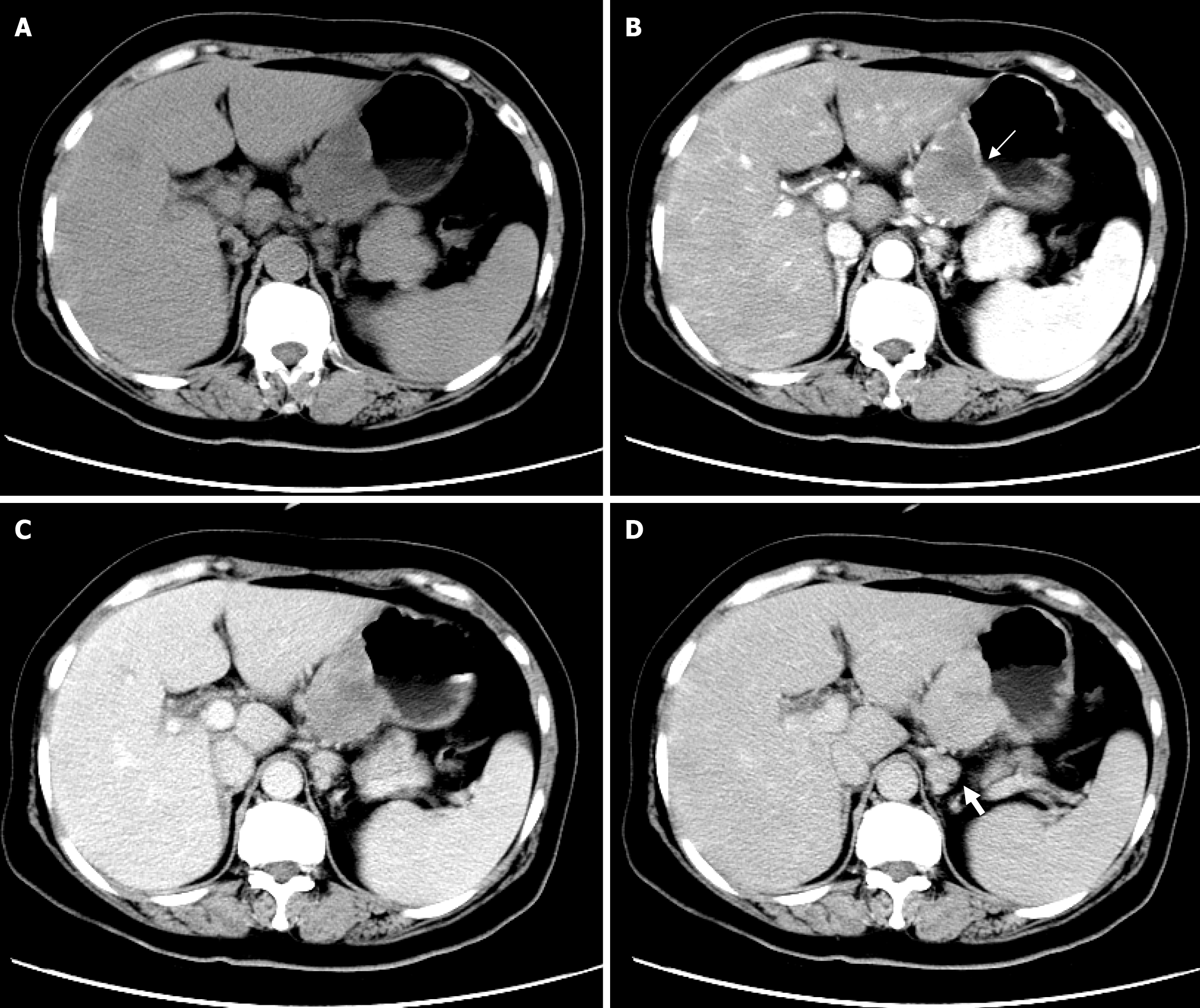

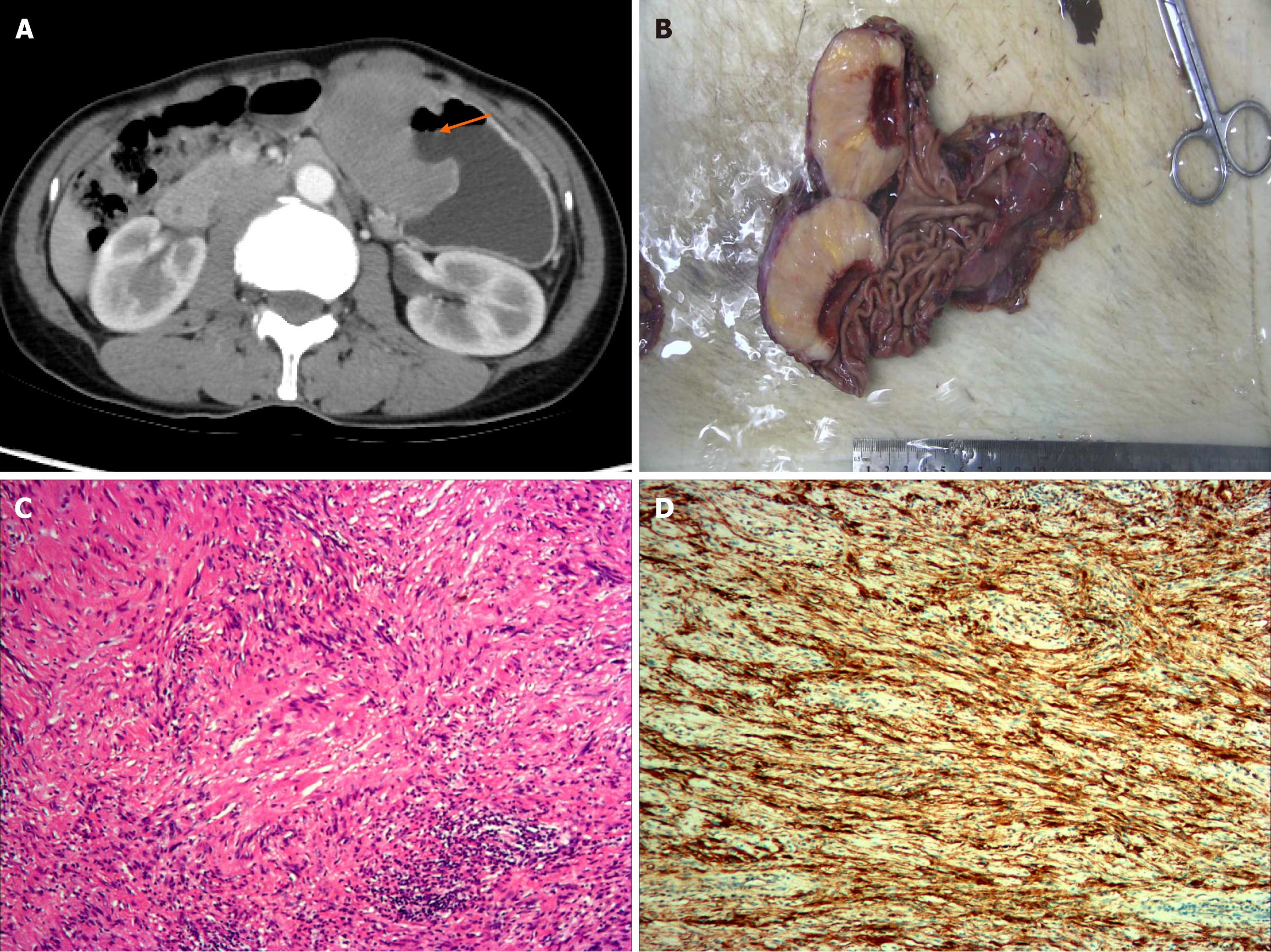

Clinical and CT imaging characteristics of GS are shown in Table 1. Representative cases are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

| Characteristics | n = 23 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 (78.3) |

| Male | 5 (21.7) |

| Location | |

| Gastric body (greater curvature) | 8 (34.8) |

| Gastric body (lesser curvature) | 10 (43.5) |

| Gastric antrum | 2 (8.7) |

| Gastric fundus | 3 (13.0) |

| Growth pattern | |

| Endoluminal | 3 (13.0) |

| Exophytic | 10 (43.5) |

| Mixed | 10 (43.5) |

| Contour | |

| Oval | 20 (87.0) |

| Lobulated | 3 (13.0) |

| Ulcered | 8 (34.8) |

| Homogeneity | |

| Homogeneous | 18 (78.3) |

| Cystic or necrosis | 3 (13.0) |

| Calcification | 4 (17.4) |

| Perigastric lymph nodes | 15 (65.0) |

Our study included 18 females (78.3%) and five males (21.7%), with a mean age of 53.4 ± 10.5 years (range: 29-77 years). Clinical manifestations included asymptomatic (n = 14, 42.4%), epigastric pain (n = 5, 15.2%), epigastric discomfort (n = 11, 33.3%), black stool (n = 3, 9.1%), bleeding (n = 1, 3.0%), and palpable mass (n = 1, 3.0%). No patient had a history of neurofibromatosis. Asymptomatic cases were incidentally detected during medical examinations such as gastroscopy or CT scans.

The tumors were predominantly located in the gastric body (78.3%), with 10 in the lesser curvature (43.5%) and eight in the greater curvature (34.8%). The growth patterns were mainly exophytic (36.7%) and mixed (46.7%). The mean maximum tumor diameter was 45.7 mm ± 24.6 mm (range: 15.0 mm-119.5 mm). Mucosal ulceration was observed in eight cases, with neat margins. Of these, two cases were endoluminal, three were exophytic, and the remaining three showed a mixed growth pattern. PLNs were observed in 15 cases (65%) with a short diameter reaching up to 25 mm. These lymph nodes were oval rather than round, mostly with a visible lymphatic hilum, and all demonstrated moderate to marked homogeneous enhancement without cystic change. In eight of these 15 cases, the lymph nodes were associated with blurring of the surrounding fat. Other features, such as contour and homogeneity, are summarized in Table 1.

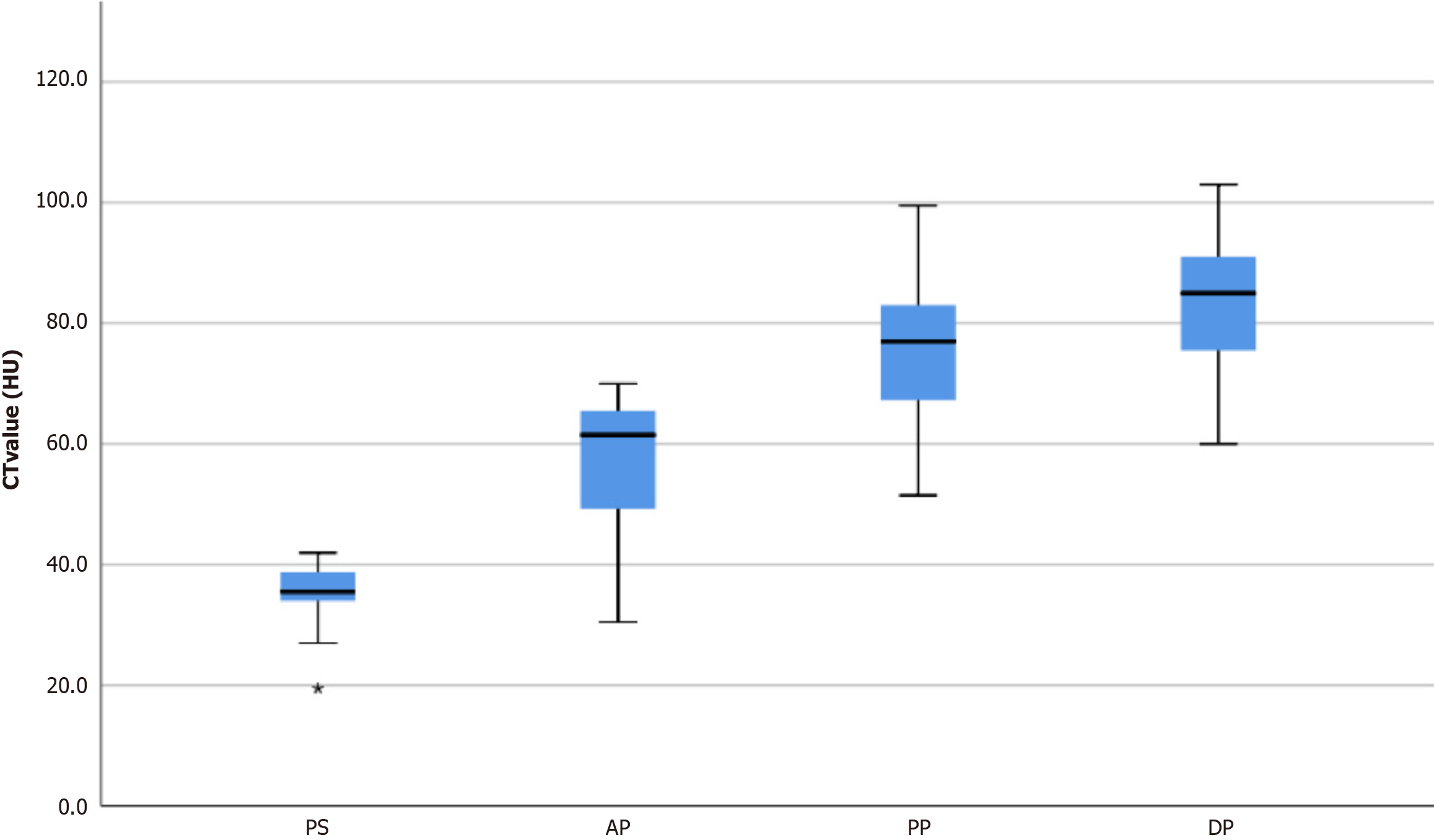

The CT value of all 23 GSs in the plain phase was 35.5 ± 5.1 HU, lower than that of the erector spinae (51.8 ± 4.5 HU). Triple-phase contrast-enhanced CT of the 23 GSs showed that the CT value in the plain phase was 35.5 ± 5.1 HU (range: 19.5-42.0 HU), 57.4 ± 10.8 HU (range: 30.5-70.0 HU) in the arterial phase, 75.3 ± 13.1 HU (range: 51.5-99.5 HU) in the portal phase, and 83.0 ± 10.9 HU (range: 60.0-103.0 HU) in the delayed phase, as shown in Figure 3. The peak enhancement of GSs occurred in the delayed phase in 20 cases and in the portal phase in three cases. The degree of enhancement of masses was 48.3 ± 10.5 HU (range: 26.0-71.0 HU), with only four cases showing enhancement below 40 HU.

The location and size of GSs were consistent with the CT findings. Gross examination of the tumors revealed yellow, yellowish, or gray-white cut surfaces. Mucosal ulceration was observed in eight cases (34.8%). Microscopic examination showed that the tumors consisted mainly of short, spindle-shaped cells without nuclear atypia in all cases. Most cases showed lymphocytic cuffing in the peripheral area. Fifteen cases presented with visible PLNs, suggesting reactive inflammatory changes without neoplastic cells. Immunohistochemical analyses showed strong positive staining for S-100 protein and negative staining for CD117 and SMA in all cases (100%). The expression of Ki-67 in 22 cases was generally weak (range, 1%-15%; median: 5%).

Spearman correlation analysis indicated a moderate positive correlation between ulceration and size (r = 0.564), size and cystic changes (r = 0.526), and a weak positive correlation between PLNs and size (r = 0.447), calcification and size

GSs are rare mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. The low incidence is evident in our study, as only 23 pathologically confirmed cases were identified more than a decade ago at the two independent large tertiary hospitals. A previous study estimated a ratio of approximately 45 gastric GISTs for each GS[13], although another study suggested that approximately nine cases of gastric GIST were observed for each case of GS[5]. GS is more prevalent in women aged 50 to 60 years. The female-to-male ratio in this study is 18:5, which is consistent with previous studies reporting a female-to-male ratio of 2:1 to 4:1[5,13]. Patients with GS often present with nonspecific symptoms. In our study, approximately half (42.4%) of the cases were asymptomatic and incidentally detected during medical examinations, while the others presented with epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, black stools, and palpable masses. Previous studies have shown that patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 are more susceptible to GSs[14]. In this study, however, all patients were confirmed to have no history of neurofibromatosis, effectively excluding the influence of gene mutations associated with this condition.

The GS prediction sites were mostly the gastric body (78.3%), especially the lesser curvature (46.7%), which is consistent with a previous study[11]. Regarding biological behavior, GS is typically a benign, slow-growing tumor with no recurrence or metastasis after surgical removal. However, a few reports have described malignant schwannomas[15-17].

CT imaging reveals that GSs are typically oval and well-defined, with only a few being lobulated (3/23). Wang et al[18] found that lobulated GSs were generally larger; however, one of our three lobulated cases was relatively small (35 mm), leading us to suspect that lobulation may not necessarily correlate with the tumor size. In our sample, the growth pattern of GS was predominantly exophytic (43.5%) and mixed (43.5%), while endoluminal tumors accounted for only 13.0%, consistent with a previous report[12]. The masses were hypodense relative to the erector spinae and mostly homo

Ulceration was detected in approximately one-third of our sample (34.8%), presenting as a focal defect of the endoluminal side. The ulcer margins were smooth rather than irregular. A previous study[19] showed that tumors with an endoluminal or mixed growth pattern were more prone to mucosal ulceration. However, in our sample, the incidence of ulceration in exophytic cases was similar to that in endoluminal cases. This finding suggests that ulcer formation may be influenced not only by tumor growth pattern but also by tumor size.

Enlargement of the PLNs is a characteristic presentation of GS. The incidence rate of this feature in our study was 65% (15/23), while in other studies it ranged from 23.7% to 81.3%[12,18,19]. All of these peripheral lymph nodes, showing moderate to marked homogeneous enhancement, were pathologically confirmed as reactive inflammatory hyperplasia rather than metastasis. Correlation analysis also indicated that the presence of reactive lymph node hyperplasia is related to both the size of the mass and ulceration. This seems counterintuitive as tumors with enlarged lymph nodes are often malignant. Additionally, eight of the 15 cases presenting with enlarged PLNs were accompanied by blurring of the surrounding fat. This may be related to the characteristic peripheral cuff of lymphoid aggregates observed in pathology.

Ki-67 protein has been widely used as a marker of tumor proliferation in human cells due to its roles in both interphase and mitotic cells[20]. In our study, all 22 cases with Ki-67 staining were positive at varying levels, but all were below 20% (range: 1%-15%; median: 5%), indicating mild proliferation, consistent with a previous finding[5]. However, Zhong et al[21] reported an exceptional instance in which the Ki-67 index reached 50%. We found that the Ki-67 index did not correlate with tumor size, reactive lymph node hyperplasia, ulceration, or cystic changes.

Distinguishing GS from other submucosal tumors, such as leiomyomas, lymphomas, and especially GIST, can be challenging in radiological diagnosis. In fact, all of our misdiagnosed cases were incorrectly identified as GIST, the most common submucosal tumor of the stomach. Compared to GS, GIST often appears cystic and heterogeneous. High-risk GIST shows signs of infiltration[6,22] but rarely has visible PLNs. However, GIST can occasionally be homogeneous and even accompanied by enlarged PLNs. In such cases, CD117 positivity confirmed by immunohistochemistry is required for diagnosis[23]. Gastric leiomyoma is usually a well-circumscribed homogeneous submucosal mass that closely resembles GS. The involvement of esophagogastric junction has been reported as an important distinguishing feature[24,25]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has reported enlarged PLNs in patients with gastric leiomyomas. Finally, gastric lymphoma commonly presents as a patch of the thickened stomach wall and is accompanied by adenopathy in the adjacent mesenteries and retroperitoneum[26].

This study has some limitations. First, it was based on retrospective data collected from two hospitals using different CT scanners, which may have introduced imaging bias. Second, due to the rarity of GS, the sample size was small despite data being collected over 10 years from two large tertiary general hospitals. Future studies may benefit from longer multicenter data collection to achieve a larger sample size. Finally, cases of other gastric submucosal tumors, such as GISTs and leiomyomas, were not included in this study. Comparative studies are needed to systematically clarify the differences between these highly similar tumors.

Our results suggest that GS predominantly occurs in middle-aged women without GS-specific symptoms. The tumor usually appears as an oval and well-defined gastric submucosal mass that grows exophytically or both exophytically and endoluminally. The plain CT scan showed a slightly hypodense mass compared to the erector spinae. With contrast, GS exhibits progressive and homogeneous enhancement with peak enhancement detected in the delayed phase. The visible PLNs around the GS have been confirmed as reactive inflammatory hyperplasia, an important feature for differentiation from other gastric submucosal tumors.

| 1. | Hilton DA, Hanemann CO. Schwannomas and their pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:205-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El Sayed L, H Masmejean E, Lavollé A, Biau D, Peyre M. Clinical results after surgical resection of benign solitary schwannomas: A review of 150 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108:103281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daimaru Y, Kido H, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Benign schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qi Z, Yang N, Pi M, Yu W. Current status of the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal schwannoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Tao K, Chang W, Zhao E, Deng R, Gao J, Cai K, Wang G, Zhang P. Clinicopathologic Features of Gastric Schwannoma: 8-Year Experience at a Single Institution in China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Min YW, Park HN, Min BH, Choi D, Kim KM, Kim S. Preoperative predictive factors for gastrointestinal stromal tumors: analysis of 375 surgically resected gastric subepithelial tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:631-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin YN, Chen MY, Tsai CY, Chou WC, Hsu JT, Yeh CN, Yeh TS, Liu KH. Prediction of Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors before Operation: A Retrospective Analysis of Gastric Subepithelial Tumors. J Pers Med. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schaefer IM, DeMatteo RP, Serrano C. The GIST of Advances in Treatment of Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022;42:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga T, Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2806-2817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 10. | Deprez PH, Moons LMG, OʼToole D, Gincul R, Seicean A, Pimentel-Nunes P, Fernández-Esparrach G, Polkowski M, Vieth M, Borbath I, Moreels TG, Nieveen van Dijkum E, Blay JY, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of subepithelial lesions including neuroendocrine neoplasms: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2022;54:412-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ji JS, Lu CY, Mao WB, Wang ZF, Xu M. Gastric schwannoma: CT findings and clinicopathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:1164-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang W, Cao K, Han Y, Zhu X, Ding J, Peng W. Computed tomographic characteristics of gastric schwannoma. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:1975-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Voltaggio L, Murray R, Lasota J, Miettinen M. Gastric schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases and critical review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:650-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Belakhoua SM, Rodriguez FJ. Diagnostic Pathology of Tumors of Peripheral Nerve. Neurosurgery. 2021;88:443-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takemura M, Yoshida K, Takii M, Sakurai K, Kanazawa A. Gastric malignant schwannoma presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bees NR, Ng CS, Dicks-Mireaux C, Kiely EM. Gastric malignant schwannoma in a child. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:952-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gennatas CS, Exarhakos G, Kondi-Pafiti A, Kannas D, Athanassas G, Politi HD. Malignant schwannoma of the stomach in a patient with neurofibromatosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1988;14:261-264. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wang J, Zhang W, Zhou X, Xu J, Hu HJ. Simple Analysis of the Computed Tomography Features of Gastric Schwannoma. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2019;70:246-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ahmed M. Recent advances in the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3142-3155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Sun X, Kaufman PD. Ki-67: more than a proliferation marker. Chromosoma. 2018;127:175-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 82.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhong Z, Xu Y, Liu J, Zhang C, Xiao Z, Xia Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Xu Q, Lu Y. Clinicopathological study of gastric schwannoma and review of related literature. BMC Surg. 2022;22:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | He MY, Zhang R, Peng Z, Li Y, Xu L, Jiang M, Li ZP, Feng ST. Differentiation between gastrointestinal schwannomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors by computed tomography. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:3746-3752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Choi YR, Kim SH, Kim SA, Shin CI, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Han JK, Choi BI. Differentiation of large (≥ 5 cm) gastrointestinal stromal tumors from benign subepithelial tumors in the stomach: radiologists' performance using CT. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:250-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yang HK, Kim YH, Lee YJ, Park JH, Kim JY, Lee KH, Lee HS. Leiomyomas in the gastric cardia: CT findings and differentiation from gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:1694-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu H, Chen H, Zhang S, Peng W. Differentiation of gastric true leiomyoma from gastric stromal tumor based on biphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomographic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2014;38:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gossios K, Katsimbri P, Tsianos E. CT features of gastric lymphoma. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |