Published online Apr 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.101661

Revised: January 6, 2025

Accepted: January 20, 2025

Published online: April 15, 2025

Processing time: 183 Days and 10 Hours

Although Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is implicated in the development of most cases of gastric cancer with autoimmune gastritis, cases of gastric cancer have been reported in patients testing negative for H. pylori. Here, we aimed to outline the current research status of the factors involved in the development of gastric cancer in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. Predictive pathological con

Core Tip: Although in cases of autoimmune gastritis, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is often implicated in gastric cancer development, there are reports of gastric cancer in patients with H. pylori-negative cases. Pathological factors for the development of gastric cancer in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis include severe atrophy, hypergastrinemia, bile reflux, and low acidity. In the diagnosis of H. pylori infection in autoimmune gastritis, it is difficult to accurately diagnose cases of previous infection. When current H. pylori infection is ruled out in autoimmune gastritis sparing antrum, the patient is considered H. pylori-negative; however, this should be re-evaluated in the future.

- Citation: Kishikawa H, Nishida J. Gastric cancer in patients with Helicobacter pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(4): 101661

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i4/101661.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i4.101661

Autoimmune gastritis is characterized by the destruction of parietal cells through an autoimmune mechanism, causing the appearance of anti-parietal cell antibodies and resulting in localized atrophy of the gastric corpus[1]. It was first reported as "type A gastritis" and was considered a different disease concept from type B gastritis, which is a predominance of the antrum[2]. Autoimmune gastritis is diagnosed on the basis of the presence of two findings of “pure au

In clinical practice, autoimmune gastritis is often suspected endoscopically, suggesting that the endoscopic images are also characteristic. The "corpus dominant advanced atrophy," in which the atrophy of the antrum is less severe than that of the gastric body, is the most common finding for the initial diagnosis, and advanced atrophy extending to the greater curvature of the gastric body, hyperplastic polyps, and sticky mucus are useful endoscopic findings[6,7]. Hypergastrinemia was reported as a risk factor for polyps (most of which are hyperplastic polyps)[8]. The study by Jin et al[9] published in the recent issue of the World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology also explored endoscopic findings of au

Here, we aimed to outline the current research status of the factors involved in the development of gastric cancer, especially in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis cases.

The incidence of gastric cancer complicating autoimmune gastritis ranges from 2.4%-9.8%[15-17]. Gastric cancer occurring in autoimmune gastritis often occurs in the proximal region, is usually discovered when detecting pernicious anemia, has a low metastasis rate and good prognosis, and is often the protruding type[18,19]. There are a few reports examining risk factors for gastric cancer associated with autoimmune gastritis. A study comparing autoimmune gastritis-associated gastric cancer with non- autoimmune gastritis reported that the incidence of pernicious anemia as an endoscopic trigger was significantly higher [odds ratio (OR), 22.0] in autoimmune gastritis-associated gastric cancer[19]. A meta-analysis reported that patients with pernicious anemia had a 6.8-fold (95%CI: 2.6-18.1) higher relative risk of having gastric cancer compared to those without[20]. Given that most cases of pernicious anemia are caused by autoimmune gastritis, the risk of gastric cancer in patients with autoimmune gastritis and pernicious anemia should be considered.

There have been several reports on the mechanism of gastric cancer carcinogenesis in autoimmune gastritis. A recent report suggested that methylation of the promoter CpG island of the tumor suppressor gene was weaker in autoimmune gastritis than in H. pylori gastritis, and the expression levels of IL1B and IL8 secreted by macrophages were also lower[21]. The authors concluded that this could explain the lower incidence of gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis than in H. pylori gastritis; however, since it was also higher in autoimmune gastritis than in healthy people, it could also be interpreted as an explanation for carcinogenesis in autoimmune gastritis.

Some studies report that incomplete intestinal metaplasia is lower in autoimmune gastritis than in H. pylori gastritis, and this is thought to explain the low rate of carcinogenesis in autoimmune gastritis. However, this is not usually seen in healthy individuals and may be involved in the carcinogenesis of autoimmune gastritis[22]. Recently, there have been some interesting reports about this incomplete intestinal metaplasia. In both autoimmune gastritis and H. pylori gastritis, a metaplastic cell subtype similar to incomplete intestinal epithelial metaplasia, characterized by the expression of the cancer-related biomarker ANPEP/CD13, has been observed and is attracting attention as a mechanism of carcinogenesis in autoimmune gastritis[23].

There is a debate about the relationship between gastric cancer and H. pylori infection in autoimmune gastritis. Many cases of stomach cancer that develop in autoimmune gastritis are associated with current or past H. pylori infection. Two previous reports on this subject state that H. pylori infection is essential for the development of stomach cancer in autoimmune gastritis. Rugge et al[24] observed 211 patients with H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis over 7.5 years and found that six cases of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia occurred but not gastric cancer or high-grade dysplasia; thus, they concluded that invasive gastric cancer does not occur in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. Moreover, they suggested that the high frequency of pseudo pyloric metaplasia, which is protective against neoplastic changes, in the body of the stomach in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis may prevent cancer development. Their definition of autoimmune gastritis was based on the following strict criteria: The presence of either corpus-restricted or dominant inflammation and the exclusion of current and past H. pylori infection by multiple modalities. Additionally, Miceli et al[25] reported that in a 20-year follow-up of 282 patients with autoimmune gastritis, excluding those with persistent H. pylori infection, and atrophic pangastritis, they did not find any cases of advanced gastric cancer, as did Rugge et al[24].

As H. pylori can be eradicated with antibiotics, it would be interesting to know if there is a relationship between H. pylori eradication and gastric cancer development in autoimmune gastritis. Some reports state that autoimmune gastritis improves with H. pylori eradication, while others say it gets worse. Those stating that autoimmune gastritis improves with H. pylori eradication[26,27] suggest a mechanism in which H. pylori and autoimmune gastritis share a common antigen[28], and the report that H. pylori eradication worsens the condition[29] suggests a mechanism in which H. pylori suppresses the Th1 response that promotes autoimmune gastritis[30], and no definitive view has been reached. Therefore, although eradication is desirable in autoimmune gastritis, it is unclear whether H. pylori eradication suppresses or promotes the development of gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis.

There are a small number of reports of gastric cancer developing in H. pylori-negative cases of autoimmune gastritis. Weise et al[19], who investigated this in a longitudinal study, reported 14 cases of H. pylori-negative gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis. Unfortunately there is no description of the details of this clinical picture. We published a case report and literature review of five cases of gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis, where H. pylori infection was strictly excluded[31]. In these cases, two or more tests for H. pylori infection were negative, with no medical history of era

Unlike H. pylori-infected gastritis, autoimmune gastritis has the following clinicopathological features: Marked atrophy, low acidity and high gastrin level. These are thought to be factors that directly cause gastric cancer, so we will discuss them below, as shown in Table 1.

| Item | Related factors |

| Autoimmune gastritis related factors | Hypergastrinemia |

| Bile acid reflux | |

| Advanced gastric mucosal atrophy | |

| Hypoacidity and the resultant overgrowth of bacteria | |

| Non-autoimmune gastritis related factors predicted by Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric cancer | Cigarette smoking |

| Family history of gastric cancer |

Hypergastrinemia: Unlike H. pylori gastritis, in pure autoimmune gastritis, G cells in the antrum are not destroyed and gastric acidity is extremely low; thus, compensatory hypergastrinemia is often observed. Accordingly, several reports have suggested that the serum gastrin level can be used to differentiate autoimmune gastritis from H. pylori gastritis[32-34].

Hypergastrinemia increases the risk of proximal gastric cancer and intestinal-type gastric cancer by ORs of 6.1 and 3.8, respectively[35], and gastric cancer with hypergastrinemia may have a poor prognosis and short survival time[36]. Additionally, the administration of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which pharmacologically induce hypergastrinemia, increases the risk of gastric cancer by 3.38 times[37], and a meta-analysis suggested that PPIs increase the development of gastric cancer[38]. There are few reports discussing the relationship between PPIs and carcinogenesis in autoimmune gastritis, but there is a report that the incidence of gastric neoplastic lesions (low-grade dysplasia to carcinoma) is high, with an OR of 9.6 in patients with autoimmune gastritis prescribed PPIs for 12 months or more[39]. It is thought that PPIs act on the remaining parietal cells in autoimmune gastritis to further increase gastrin production. Hence, these findings raise the possibility that hypergastrinemia may induce carcinogenesis in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis, as in H. pylori gastritis.

Bile acid reflux: Gastric mucosal damage caused by bile acid reflux may induce gastric cancer. Bile acid reflux may be an independent factor in the development of gastric cancer[40], or a risk factor for gastric cancer and precancerous lesions[41]. In advanced autoimmune gastritis, gastric acid secretion is highly suppressed; consequently, it is believed that the gastric mucosal damage caused by the alkalis associated with bile acid reflux may be more severe in advanced autoimmune gastritis than in H. pylori gastritis. Moreover, this may be particularly associated with a greater curvature of the proximal and posterior parts of the gastric body in gastric cancer due to the fluidity and gravity of the bile juice. Similarly, bile reflux may increase the possibility of carcinogenesis in the body of the stomach, where gastric cancer often occurs in patients with autoimmune gastritis.

Gastric mucosal atrophy: Gastric mucosal atrophy also causes gastric cancer. The risk of gastric cancer increases when the atrophy grade is open type according to the Kimura―Takemoto classification[42] and when it is a stage III/IV ac

The low pepsinogen I and I/II ratios indicate severe atrophy of the gastric corpus and are the theoretical basis for serological gastric cancer screening methods such as the ABC method. The fact that most reported cases of gastric cancer in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis also have low pepsinogen levels suggests that severe atrophy may be involved in carcinogenesis in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. It remains unknown whether gastric mucosal atrophy caused by purely autoimmune mechanisms can lead to the development of gastric cancer; however, it seems theoretically unlikely that in autoimmune gastritis, which is often associated with inflammatory cell infiltration and metaplasia, severe atrophy does not lead to the development of gastric cancer.

Hypoacidity and bacterial overgrowth: Hypoacidity occurs at a higher rate in patients with gastric cancer than in healthy individuals[45]. In autoimmune gastritis, hypoacidity increases the number of bacteria that are normally present, in

Regarding factors not related to the pathophysiology of autoimmune gastritis, although their involvement may be low, they are thought to be risk factors for gastric cancer development in autoimmune gastritis in H. pylori-negative cases as shown in Table 1. It is reasonable to assume that risk factors for gastric cancer development in H. pylori-negative cases may also be involved in carcinogenesis in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. Smoking and family history of gastric cancer have been reported as risk factors for H. pylori-negative gastric cancer[49]. Smoking has been reported as a significant risk factor for gastric cancer in several meta-analyses[50,51]. The association between gastric cancer and family history has also been reported in a meta-analysis[52], and since the pathogenesis of H. pylori-negative gastric cancer may be determined by genetic predisposition[53], it is possible that genetic factors are involved not only in H. pylori-negative cases without atrophy, but also in H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmune gastritis has more risk factors for carcinogenesis than H. pylori-negative gastritis, and it is reasonable to think that carcinogenesis due to these factors such as smoking and family history can occur.

H. pylori has been implicated in the development of gastric cancer in patients with autoimmune gastritis. However, the role of H. pylori infection in the development of all gastric cancer cases among patients with autoimmune gastritis remains unclear. Globally, the number of cases of gastric cancer is on the decrease, reflecting the decline in the rate of infection with H. pylori, but the number of cases of gastric cancer in people who have not been infected with H. pylori is on the rise[54]. In contrast to these H. pylori-negative cases, H. pylori-negative autoimmune gastritis cases exhibit numerous factors that induce carcinogenesis. The factors directly related to the pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritis are as follows: (1) Severe atrophy; (2) Hypergastrinemia; (3) Low acidity; and (4) Bile reflux. In addition, smoking and family history are not involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune gastritis, but they may be risk factors for gastric cancer even in H. pylori-negative individuals. This is also thought to be the case for autoimmune gastritis. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that patients with autoimmune gastritis, even in H. pylori-negative cases, face a markedly higher risk of cancer de

If the underlying cause of autoimmune gastritis can be treated and the atrophy ameliorated (e.g., by immunomodulating medications), surveillance may not be required. However, it seems prudent to carefully monitor patients with autoimmune gastritis with endoscopic examinations to assess the possibility of gastric cancer development, whether they have H. pylori infection or not.

A significant challenge in discussing the relationship between carcinogenesis of autoimmune gastritis and H. pylori is the lack of established criteria for diagnosing current or past H. pylori infection in patients with autoimmune gastritis.

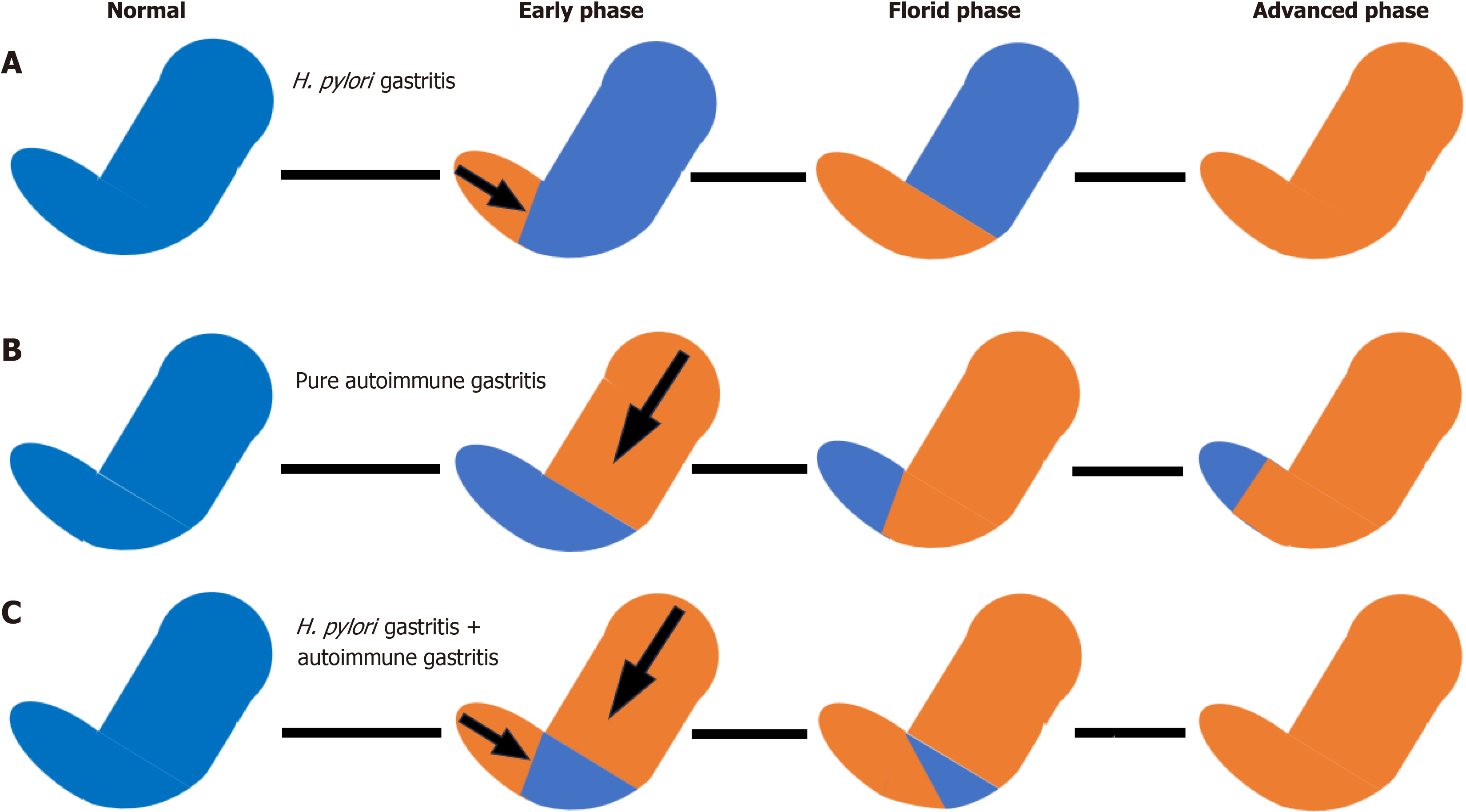

Since H. pylori may disappear spontaneously in patients with severe gastric mucosal atrophy[55], a negative H. pylori test result and no past medical history of eradication treatment cannot rule out past infection. In such cases, histological confirmation of previous H. pylori infection is necessary. The widely accepted histological definition of a H. pylori-negative state in autoimmune gastritis involves histological findings consistent with autoimmune gastritis in the corpus of the stomach, sparing the antrum, as shown in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the generally accepted interpretation for evaluating the presence or absence of H. pylori infection in autoimmune gastritis. In H. pylori gastritis, atrophy progresses from the antrum, and in advanced cases, pangastritis develops. In autoimmune gastritis without H. pylori infection, gastritis progresses from the body of the stomach but does not involve the antrum. In autoimmune gastritis with H. pylori infection, atrophy begins in both the antrum and the corpus, and in advanced cases, pangastritis develops. There are two problems with this view: (1) It is difficult to differentiate the etiology when pangastritis is observed; and (2) The question remains whether an antrum showing normal histologic findings without atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and inflammatory cell infiltration truly represents a case of uninfected H. pylori. Histological atrophy of the antrum can improve over time following H. pylori eradication[56,57], suggesting that the current histological definition of H. pylori negativity in patients with autoimmune gastritis may require re-evaluation.

| Definition |

| Exclusion of past medical history of Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment |

| Exclusion of a current Helicobacter pylori infection as assessed by a multiple Helicobacter pylori test |

| Confirmation of absence of previous Helicobacter pylori infection as assessed by histologic findings of corpus predominant atrophy with sparing of the antrum |

To verify this, a cohort study should be conducted involving patients with autoimmune gastritis who are definitively infected with H. pylori and the histologic changes and clinical findings observed over a long period of time before and after successful eradication treatment.

Although H. pylori is presumably involved in many cases of gastric cancer development among patients with autoi

We would like to thank Dr. Kenji Nakamura, Department of Gastroenterology, Ichikawa General Hospital, Tokyo Dental College, for his constructive criticism of this manuscript.

| 1. | Lenti MV, Rugge M, Lahner E, Miceli E, Toh BH, Genta RM, De Block C, Hershko C, Di Sabatino A. Autoimmune gastritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bordin D, Livzan M. History of chronic gastritis: How our perceptions have changed. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1851-1858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis--pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:529-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rugge M, Genta RM, Malfertheiner P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, El-Serag H, Graham DY, Kuipers EJ, Leung WK, Park JY, Rokkas T, Schulz C, El-Omar EM; RE. GA.IN.: the Real-world Gastritis Initiative-updating the updates. Gut. 2024;73:407-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coati I, Fassan M, Farinati F, Graham DY, Genta RM, Rugge M. Autoimmune gastritis: Pathologist's viewpoint. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12179-12189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Kamada T, Watanabe H, Furuta T, Terao S, Maruyama Y, Kawachi H, Kushima R, Chiba T, Haruma K. Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kamada T, Maruyama Y, Monobe Y, Haruma K. Endoscopic features and clinical importance of autoimmune gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Massironi S, Elvevi A, Gallo C, Laffusa A, Tortorella A, Invernizzi P. Exploring the spectrum of incidental gastric polyps in autoimmune gastritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55:1201-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jin JZ, Liang X, Liu SP, Wang RL, Zhang QW, Shen YF, Li XB. Association between autoimmune gastritis and gastric polyps: Clinical characteristics and risk factors. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2025;17:92908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 10. | Notsu T, Adachi K, Mishiro T, Fujihara H, Toda T, Takaki S, Kinoshita Y. Prevalence of Autoimmune Gastritis in Individuals Undergoing Medical Checkups in Japan. Intern Med. 2019;58:1817-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rustgi SD, Bijlani P, Shah SC. Autoimmune gastritis, with or without pernicious anemia: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical management. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211038771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen C, Yang Y, Li P, Hu H. Incidence of Gastric Neoplasms Arising from Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis: A Systematic Review and Case Reports. J Clin Med. 2023;12:1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Ruffilli I, Elia G, Biricotti M, Vita R, Benvenga S, Antonelli A. The association of other autoimmune diseases in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis: Review of the literature and report of a large series of patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:1125-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang GT, Zhao HY, Kong Y, Sun NN, Dong AQ. Correlation between serum vitamin B12 level and peripheral neuropathy in atrophic gastritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1343-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dilaghi E, Dottori L, Pivetta G, Dalla Bella M, Esposito G, Ligato I, Pilozzi E, Annibale B, Lahner E. Incidence and Predictors of Gastric Neoplastic Lesions in Corpus-Restricted Atrophic Gastritis: A Single-Center Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:2157-2165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Terao S, Suzuki S, Yaita H, Kurahara K, Shunto J, Furuta T, Maruyama Y, Ito M, Kamada T, Aoki R, Inoue K, Manabe N, Haruma K. Multicenter study of autoimmune gastritis in Japan: Clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Park JY, Cornish TC, Lam-Himlin D, Shi C, Montgomery E. Gastric lesions in patients with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) in a tertiary care setting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1591-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kitamura S, Muguruma N, Okamoto K, Kagemoto K, Kida Y, Mitsui Y, Ueda H, Kawaguchi T, Miyamoto H, Sato Y, Aoki R, Shunto J, Bando Y, Takayama T. Clinicopathological characteristics of early gastric cancer associated with autoimmune gastritis. JGH Open. 2021;5:1210-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Weise F, Vieth M, Reinhold D, Haybaeck J, Goni E, Lippert H, Ridwelski K, Lingohr P, Schildberg C, Vassos N, Kruschewski M, Krasniuk I, Grimminger PP, Waidmann O, Peitz U, Veits L, Kreuser N, Lang H, Bruns C, Moehler M, Lordick F, Gockel I, Schumacher J, Malfertheiner P, Venerito M. Gastric cancer in autoimmune gastritis: A case-control study from the German centers of the staR project on gastric cancer research. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vannella L, Lahner E, Osborn J, Annibale B. Systematic review: gastric cancer incidence in pernicious anaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:375-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Takeuchi C, Sato J, Yamashita S, Sasaki A, Akahane T, Aoki R, Yamamichi M, Liu YY, Ito M, Furuta T, Nakajima S, Sakaguchi Y, Takahashi Y, Tsuji Y, Niimi K, Tomida S, Fujishiro M, Yamamichi N, Ushijima T. Autoimmune gastritis induces aberrant DNA methylation reflecting its carcinogenic potential. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:144-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Genta RM, Turner KO, Robiou C, Singhal A, Rugge M. Incomplete Intestinal Metaplasia Is Rare in Autoimmune Gastritis. Dig Dis. 2023;41:369-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hoft SG, Brennan M, Carrero JA, Jackson NM, Pretorius CA, Bigley TM, Sáenz JB, DiPaolo RJ. Unveiling Cancer-Related Metaplastic Cells in Both Helicobacter pylori Infection and Autoimmune Gastritis. Gastroenterology. 2025;168:53-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rugge M, Bricca L, Guzzinati S, Sacchi D, Pizzi M, Savarino E, Farinati F, Zorzi M, Fassan M, Dei Tos AP, Malfertheiner P, Genta RM, Graham DY. Autoimmune gastritis: long-term natural history in naïve Helicobacter pylori-negative patients. Gut. 2023;72:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Miceli E, Vanoli A, Lenti MV, Klersy C, Di Stefano M, Luinetti O, Caccia Dominioni C, Pisati M, Staiani M, Gentile A, Capuano F, Arpa G, Paulli M, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. Natural history of autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a prospective, single centre, long-term experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:1172-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stolte M, Meier E, Meining A. Cure of autoimmune gastritis by Helicobacter pylori eradication in a 21-year-old male. Z Gastroenterol. 1998;36:641-643. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kotera T, Nishimi Y, Kushima R, Haruma K. Regression of Autoimmune Gastritis after Eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2023;17:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Amedei A, Bergman MP, Appelmelk BJ, Azzurri A, Benagiano M, Tamburini C, van der Zee R, Telford JL, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, D'Elios MM, Del Prete G. Molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori antigens and H+, K+ --adenosine triphosphatase in human gastric autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1147-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ihara T, Ihara N, Kushima R, Haruma K. Rapid Progression of Autoimmune Gastritis after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy. Intern Med. 2023;62:1603-1609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ohana M, Okazaki K, Oshima C, Kawasaki K, Fukui T, Tamaki H, Matsuura M, Asada M, Nishi T, Uchida K, Uose S, Nakase H, Iwano M, Matsushima Y, Hiai H, Chiba T. Inhibitory effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on murine autoimmune gastritis. Gut. 2003;52:1102-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kishikawa H, Takarabe S, Ichikawa M, Sasaki A, Nishida J. Gastric Adenocarcinoma in Helicobacter pylori-Negative Autoimmune Gastritis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2024;16:e66910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kriķe P, Shums Z, Poļaka I, Kikuste I, Vanags A, Tolmanis I, Isajevs S, Liepniece-Karele I, Santare D, Tzivian L, Rudzīte D, Song M, Camargo MC, Norman GL, Leja M. The Diagnostic Value of Anti-Parietal Cell and Intrinsic Factor Antibodies, Pepsinogens, and Gastrin-17 in Corpus-Restricted Atrophic Gastritis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:2784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kishikawa H, Nakamura K, Ojiro K, Katayama T, Arahata K, Takarabe S, Sasaki A, Miura S, Hayashi Y, Hoshi H, Kanai T, Nishida J. Relevance of pepsinogen, gastrin, and endoscopic atrophy in the diagnosis of autoimmune gastritis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:4202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Venerito M, Varbanova M, Röhl FW, Reinhold D, Frauenschläger K, Jechorek D, Weigt J, Link A, Malfertheiner P. Oxyntic gastric atrophy in Helicobacter pylori gastritis is distinct from autoimmune gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:677-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ness-Jensen E, Bringeland EA, Mattsson F, Mjønes P, Lagergren J, Grønbech JE, Waldum HL, Fossmark R. Hypergastrinemia is associated with an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma with proximal location: A prospective population-based nested case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:1879-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fossmark R, Sagatun L, Nordrum IS, Sandvik AK, Waldum HL. Hypergastrinemia is associated with adenocarcinomas in the gastric corpus and shorter patient survival. APMIS. 2015;123:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Brusselaers N, Wahlin K, Engstrand L, Lagergren J. Maintenance therapy with proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tran TH, Myung SK, Trinh TTK. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastrointestinal cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Oncol Lett. 2023;27:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dilaghi E, Bellisario M, Esposito G, Carabotti M, Annibale B, Lahner E. The Impact of Proton Pump Inhibitors on the Development of Gastric Neoplastic Lesions in Patients With Autoimmune Atrophic Gastritis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:910077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Zhang LY, Zhang J, Li D, Liu Y, Zhang DL, Liu CF, Wang N, Wu SR, Lu WQ, Guo JZ, Shi YQ. Bile reflux is an independent risk factor for precancerous gastric lesions and gastric cancer: An observational cross-sectional study. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:282-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li D, Zhang J, Yao WZ, Zhang DL, Feng CC, He Q, Lv HH, Cao YP, Wang J, Qi Y, Wu SR, Wang N, Zhao J, Shi YQ. The relationship between gastric cancer, its precancerous lesions and bile reflux: A retrospective study. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:222-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Xiao S, Fan Y, Yin Z, Zhou L. Endoscopic grading of gastric atrophy on risk assessment of gastric neoplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:55-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yue H, Shan L, Bin L. The significance of OLGA and OLGIM staging systems in the risk assessment of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:579-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Shah SC, Piazuelo MB, Kuipers EJ, Li D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Atrophic Gastritis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1325-1332.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lu PJ, Hsu PI, Chen CH, Hsiao M, Chang WC, Tseng HH, Lin KH, Chuah SK, Chen HC. Gastric juice acidity in upper gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5496-5501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Furuta T, Baba S, Yamade M, Uotani T, Kagami T, Suzuki T, Tani S, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Osawa S, Sugimoto K. High incidence of autoimmune gastritis in patients misdiagnosed with two or more failures of H. pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:370-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kawai T, Kawai Y, Akimito Y, Hamada M, Iwata E, Niikura R, Nagata N, Yanagisawa K, Fukuzawa M, Itoi T, Sugimoto M. Intragastric bacterial infection and endoscopic findings in Helicobacter pylori-negative patients. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2024;75:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Vermeer IT, Engels LG, Pachen DM, Dallinga JW, Kleinjans JC, van Maanen JM. Intragastric volatile N-nitrosamines, nitrite, pH, and Helicobacter pylori during long-term treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:517-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Morais S, Peleteiro B, Araújo N, Malekzadeh R, Ye W, Plymoth A, Tsugane S, Hidaka A, Hamada GS, López-Carrillo L, Zaridze D, Maximovich D, Aragonés N, Castaño-Vinyals G, Pakseresht M, Hernández-Ramírez RU, López-Cervantes M, Leja M, Gasenko E, Pourfarzi F, Zhang ZF, Yu GP, Derakhshan MH, Pelucchi C, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Lunet N. Identifying the Profile of Helicobacter pylori-Negative Gastric Cancers: A Case-Only Analysis within the Stomach Cancer Pooling (StoP) Project. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:200-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Rota M, Possenti I, Valsassina V, Santucci C, Bagnardi V, Corrao G, Bosetti C, Specchia C, Gallus S, Lugo A. Dose-response association between cigarette smoking and gastric cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2024;27:197-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Morais S, Rodrigues S, Amorim L, Peleteiro B, Lunet N. Tobacco smoking and intestinal metaplasia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:1031-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ligato I, Dottori L, Sbarigia C, Dilaghi E, Annibale B, Lahner E, Esposito G. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Risk of gastric cancer in patients with first-degree relatives with gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59:606-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Xu Q, Chen TJ, He CY, Sun LP, Liu JW, Yuan Y. MiR-27a rs895819 is involved in increased atrophic gastritis risk, improved gastric cancer prognosis and negative interaction with Helicobacter pylori. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nguyen TH, Mallepally N, Hammad T, Liu Y, Thrift AP, El-Serag HB, Tan MC. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Positive Non-cardia Gastric Adenocarcinoma Is Low and Decreasing in a US Population. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2403-2411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kishikawa H, Ojiro K, Nakamura K, Katayama T, Arahata K, Takarabe S, Miura S, Kanai T, Nishida J. Previous Helicobacter pylori infection-induced atrophic gastritis: A distinct disease entity in an understudied population without a history of eradication. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ruiz B, Garay J, Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, Bravo LE, Realpe JL, Mera R. Morphometric evaluation of gastric antral atrophy: improvement after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3281-3287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lahner E, Dilaghi E, Dottori L, Annibale B. Not all that is corpus restricted is necessarily autoimmune. Gut. 2023;72:2384-2385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |