Published online May 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i5.1050

Peer-review started: November 27, 2021

First decision: January 8, 2022

Revised: January 20, 2022

Accepted: April 20, 2022

Article in press: April 20, 2022

Published online: May 15, 2022

Processing time: 163 Days and 19.5 Hours

Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) is a rare malignancy with a poor prognosis. It is difficult to diagnose PHA because of the lack of specific symptoms or tumour markers, and it rapidly progresses and has a high mortality. To our knowledge, PHA has not been reported to mimic hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Herein, we present a case of PHA manifesting as hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, diagnosed using transjugular liver biopsy, that resulted in the death of the patient.

A 71-year-old man was admitted with the primary complaint of abdominal distension, decreased appetite, fatigue in the previous month, and loss of 10 kg of weight in the past 2 years. Both the liver and spleen were enlarged, and the liver had a medium-hard texture on percussion. Laboratory examinations were performed, and abdominal plain computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced CT showed hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, as well as diffuse low-density shadows distributed in the liver and spleen. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed diffuse, hypodense, nodular or flake shadows in the liver and heterogeneous enhancement in the spleen. A transjugular liver biopsy was performed. Based on the pathology results, the patient was diagnosed with hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome secondary to PHA. The patient’s status further deteriorated and he developed serious hepatic failure. The patient was discharged, and died 3 d later.

PHA is rare and has a poor prognosis; however, transjugular liver biopsy can be safely performed to aid in diagnosis.

Core Tip: To our knowledge, primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) has not been reported to mimic hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Here, we present a patient who died from PHA, which manifested as hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and was diagnosed by transjugular liver biopsy.

- Citation: Ha FS, Liu H, Han T, Song DZ. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma manifesting as hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(5): 1050-1056

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i5/1050.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i5.1050

Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) is a rare form of malignancy, accounting for 2% of all primary liver tumours. Despite the low incidence, PHA is still the most common malignant mesenchymal tumour of the liver and the third most common primary liver malignancy[1,2]. Accurate diagnosis of this tumour is usually difficult because the symptoms and signs are not specific, and tumours are difficult to distinguish radiologically from other hepatic tumours[3]. In addition, a tissue sample is required for a diagnosis, and very few patients opt to undergo a needle biopsy[4]. Herein, we report a case of PHA, which manifested as hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome.

A 71-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with the primary complaint of abdominal distension that commenced a fortnight before presentation.

The patient had ingested herbal medicine for 20 d prior, to maintain his health, but complained of decreased appetite and fatigue in the previous month, and had lost 10 kg of weight in the past 2 years.

The patient denied any history of hepatitis, diabetes mellitus, or cancer.

The patient was not a habitual drinker and did not have any significant history of exposure to carcinogenic chemicals such as thorium dioxide, vinyl chloride monomer, or arsenic.

Both the liver and spleen were enlarged, and the liver had a medium-hard texture on percussion.

Laboratory examinations on admission were as follows: White blood cell count, 6.57 × 109/L; haemoglobin, 88 g/L; platelet count, 45 × 109/L; albumin, 32.5 g/L; alanine aminotransferase, 90 U/L; aspartate transaminase, 124 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 231 U/L; γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 257 U/L; total bilirubin, 82.6 μmol/L; direct bilirubin, 48.2 μmol/L; prothrombin time, 18.9 s; international normalised ratio, 1.6; and plasma D-dimer, > 10 mg/L. Tumour markers, including α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, were within normal ranges. Screening tests for autoantibodies and viral hepatitis returned negative results.

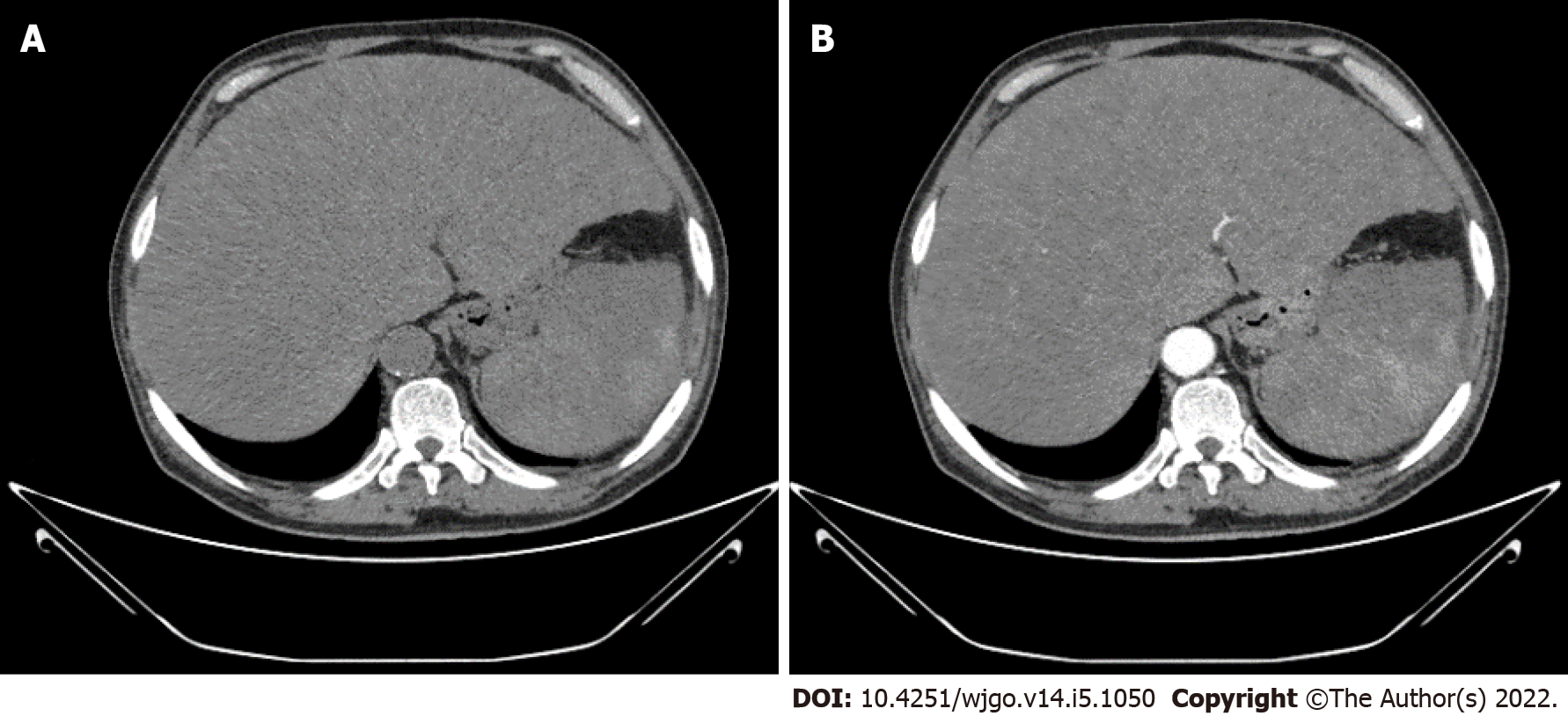

Abdominal plain computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced CT showed hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, as well as diffuse low-density shadows distributed in the liver and spleen (Figure 1A). Contrast-enhanced CT revealed diffuse, hypodense, nodular or flake shadows in the liver and heterogeneous enhancement in the spleen (Figure 1B).

The patient presented with abdominal distension, jaundice, ascites, and hepatomegaly, in conjunction with the evidence on enhanced computed tomography; in addition, Budd-Chiari syndrome was ruled out because there were no communicating branches between the narrowed hepatic veins. The patient had a history of herbal medicine intake. After excluding other known causes of liver injury, a preliminary diagnosis of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome was made; however, there remained some doubts as the herbal medicine that the patient had ingested in its common form does not contain pyrrolidine alkaloid and splenomegaly was significant in the acute phase. The occurrence of splenomegaly during the acute phase of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome is rare. A transjugular liver biopsy was subsequently performed to improve the diagnosis.

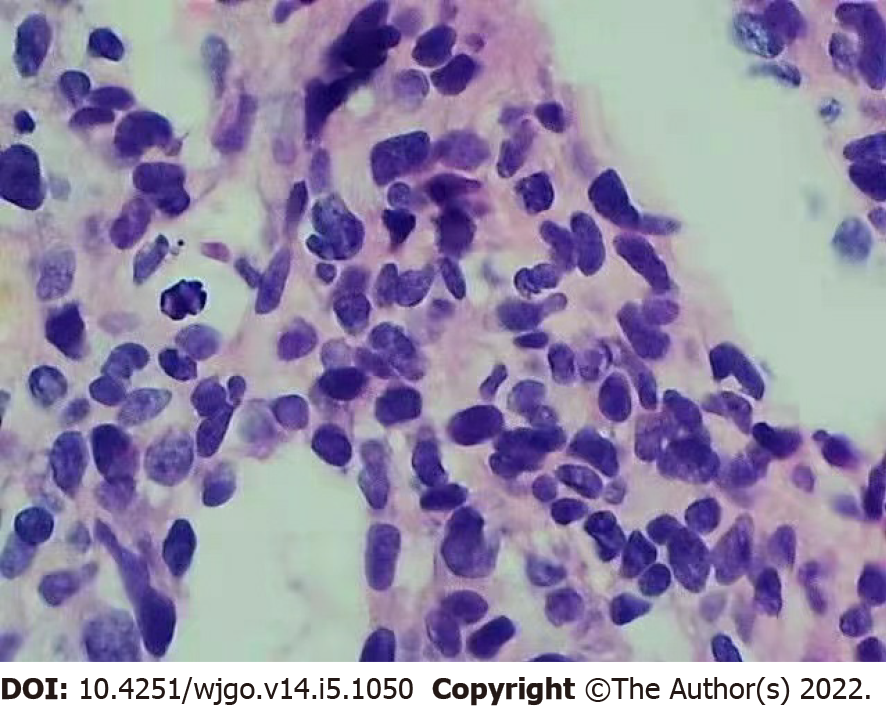

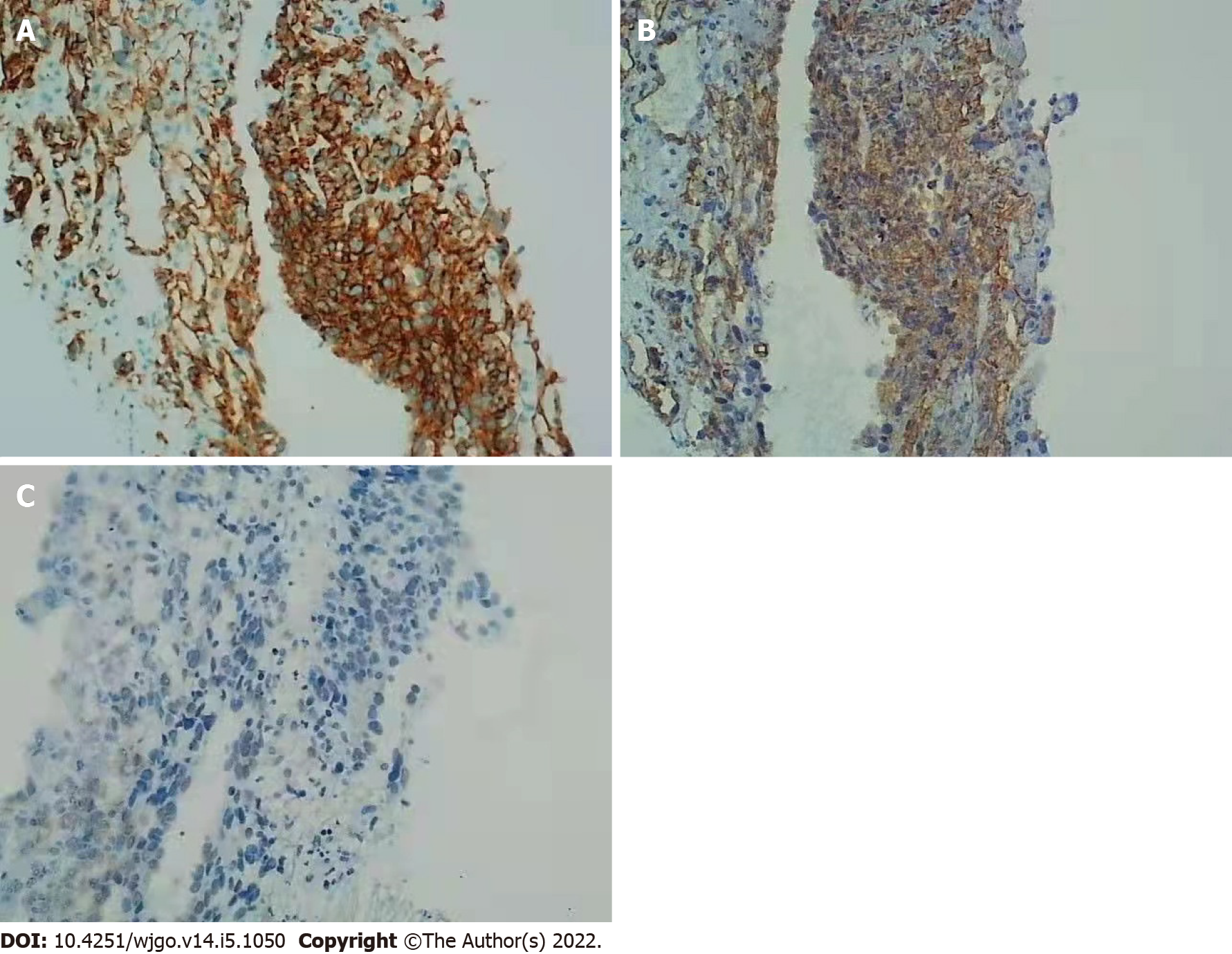

Anticoagulation therapy was administered the following day. Three days later, pathological examination of a liver biopsy sample showed that the hepatic sinusoids were obviously dilated and filled with red blood cells. Hepatocytes around the sinusoid atrophy were found. Significant cytological atypia was observed with anastomosing channels, which was suggestive of angiosarcoma (Figure 2). Immunohistochemically, the specimen was positive for CD31, CD34, and electroretinography (ERG), supporting the diagnosis of PHA (Figure 3). The Ki-67 proliferative index was almost 20%–30%. Based on the pathology results, the patient was diagnosed with hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome secondary to PHA.

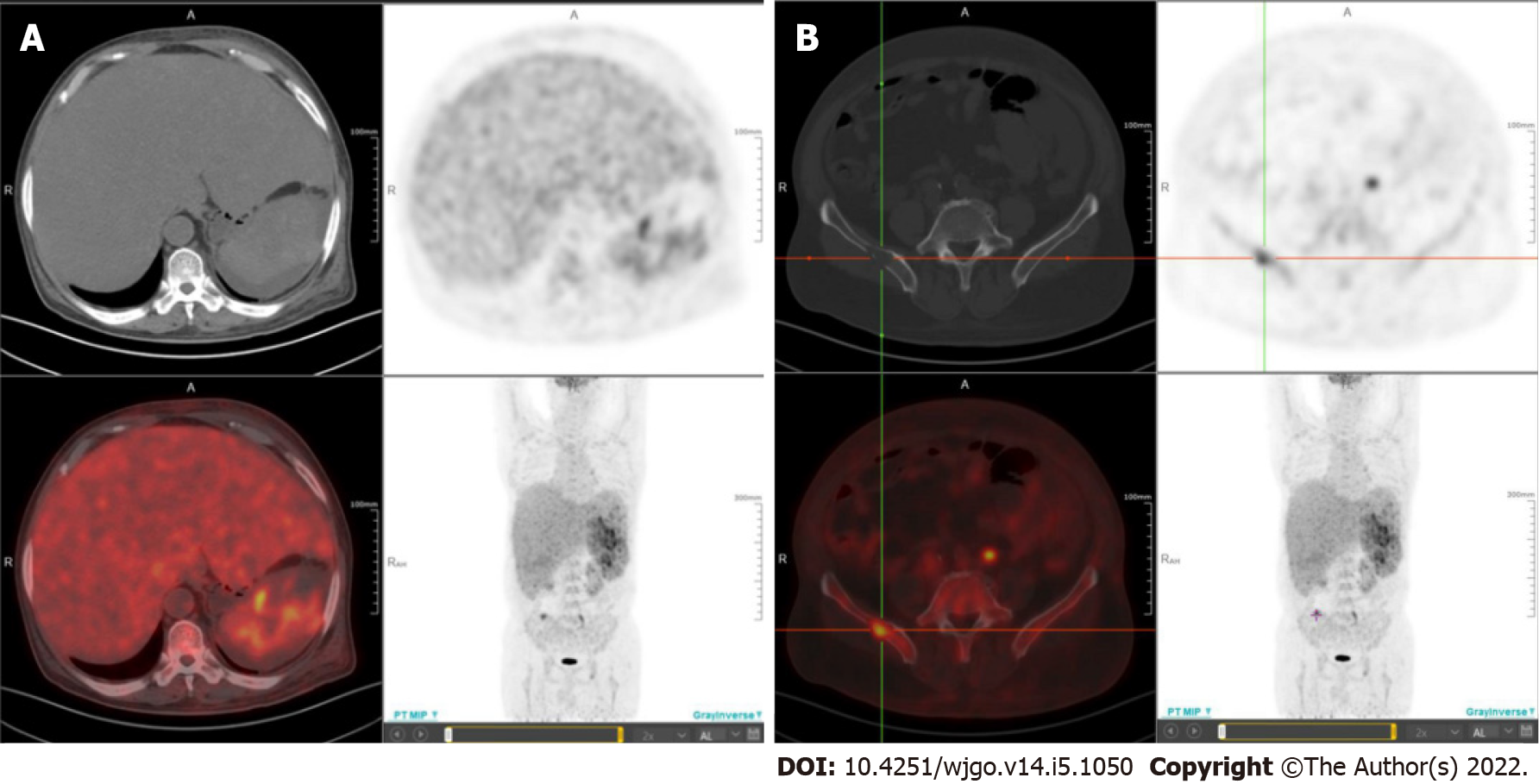

Whole-body positron emission tomography/CT fusion scanning was performed after administration of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) for staging purposes to identify metastatic sites. Diffuse areas of increased uptake were seen in the liver, which corresponded to images on CT (Figure 4A). The maximum standardised uptake value in the liver was 4.3. In addition, multiple areas of increased uptake were detected in the spleen and right ilium, suggestive of spleen dissemination (Figure 4A) and bone metastasis (Figure 4B), respectively.

The patient’s status further deteriorated, with the development of serious hepatic failure, and progressive reduction in haemoglobin levels and platelet counts. The patient complained of further aggravated abdominal distension. At the family’s request, the patient was discharged; he died 3 d later.

This case highlights the rarity and complex nature of the diagnosis of PHA. Owing to its rare occurrence, nonspecific symptomatology, nonspecific tumour makers, challenging radiographic findings, and low biopsy rate, confirming a diagnosis of PHA is difficult. The aetiology of PHA remains unclear. According to an epidemiological study, vinyl chloride monomer, thorium dioxide, arsenic, and androgenic anabolic steroids are associated with the development of PHA in 25% of all cases[5].

The symptoms of PHA are variable. Most patients have nonspecific symptoms including abdominal pain, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, fever, and low back pain, and these symptoms mimic chronic liver diseases[6]. PHA is more predominantly found in men, with a male to female diagnosis ratio of 3:1, and presents in the fifth or sixth decade of life[7].

It has been suggested that PHA can be elucidated by counting the number and size of hepatic tumours on CT images. PHA can appear as multiple nodules, a dominant mass, or a mixed pattern of a dominant mass and multiple nodules, but rarely manifests as an infiltrative, micronodular subtype[1]. In our case, the tumour manifested as an infiltrative, micronodular subtype and the findings on contrast-enhanced CT were consistent with hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome that was diagnosed as PHA.

The history of herbal medicine intake made this diagnosis more difficult. In China, hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome is often associated with the oral intake of plants that contain pyrrolidine alkaloids. Our case met the ‘Nanjing criteria’ for the diagnosis of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome except that the herbal medicine that the patient had ingested does not contain pyrrolidine alkaloid in its common form[8]. Budd-Chiari syndrome, especially the type with simple hepatic vein obstruction, can be easily misdiagnosed. Communicating branches between the narrowed hepatic veins are seen in Budd-Chiari syndrome and are a critical feature that distinguishes Budd-Chiari syndrome from other similar conditions[8].

The patient’s condition progressed rapidly. Thus, the diagnosis was questionable. A liver biopsy was necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. However, because the patient’s platelet count continued to decline and coagulation disorders and jaundice could not be controlled, a percutaneous liver biopsy was not performed, due to the associated increased risk of bleeding. There is evidence that transjugular liver biopsy is a highly efficacious, well-tolerated, and safe procedure. It can be safely performed multiple times in the same patient or in critically ill patients with severe coagulopathy and does not significantly increase the rate of complications while maintaining an extremely favourable diagnostic yield[9]. It is difficult to make a diagnosis of PHA using only a CT scan, and a biopsy might be a reasonable option; however, percutaneous liver biopsy in patients with PHA is not safe because of the vascular nature of the tumour and its tendency to haemorrhage[2]. Thus, sometimes, transjugular liver biopsy is a good choice.

Microscopic examination could show cytological atypia such as spindle-shaped cells, and immunohistochemical staining positive for CD31, CD34, ERG, and factor VIII in patients with PHA[10,11].

There is report that 18F-FDG positron emission tomography is helpful for distinguishing between PHA and giant cavernous hepatic haemangioma[8], and it can help to identify metastatic sites for staging purposes. At the time of presentation, most patients with PHA have metastatic lesions, such as lung or spleen lesions[12].

The treatment of PHA has not been defined owing to its rarity and association with high mortality. The median survival duration is 6 mo if the patient does not undergo treatment, and only 3% of patients live longer than 2 years[2]. There are several choices of treatment for patients with PHA. Ideal treatment is complete resection, especially when the tumour is limited to one segment of the liver[13]. The prognoses of these patients depend on the ability to achieve complete tumour resection[14]. However, more than 80% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stage, with only a few patients meeting the criteria for tumour resection, thus curative surgery is difficult to perform[15]. PHA is considered to be a contraindication for liver transplantation as survival is poor and recurrence rates are high[16].

PHA is also reported to be radioresistant[3]. Alternative palliative therapies, including transarterial chemoembolization and systemic chemotherapy, are considered to be effective for unresectable PHA[17,18]. Transarterial chemoembolization is useful to treat acute arterial bleeding from the liver of patients with PHA[18].

PHA is a rare malignancy with a poor prognosis. This case highlights the rarity of the disease, and the difficulty of diagnosis. Transjugular liver biopsy may be a safe choice in patients with PHA to aid in diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Ferraioli G, Italy; Ghannam WM, Egypt; Kumar A, India S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Koyama T, Fletcher JG, Johnson CD, Kuo MS, Notohara K, Burgart LJ. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: findings at CT and MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;222:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Locker GY, Doroshow JH, Zwelling LA, Chabner BA. The clinical features of hepatic angiosarcoma: a report of four cases and a review of the English literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1979;58:48-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Molina E, Hernandez A. Clinical manifestations of primary hepatic angiosarcoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:677-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kew MC, Dos Santos HA, Sherlock S. Diagnosis of primary cancer of the liver. Br Med J. 1971;4:408-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Falk H, Herbert J, Crowley S, Ishak KG, Thomas LB, Popper H, Caldwell GG. Epidemiology of hepatic angiosarcoma in the United States: 1964-1974. Environ Health Perspect. 1981;41:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu YP, Chen YM, Matro E, Chen RB, Jiang ZN, Mou YP, Hu HJ, Huang CJ, Wang GY. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: A report of two cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6088-6096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abegunde AT, Aisien E, Mba B, Chennuri R, Sekosan M. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to primary hepatic angiosarcoma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2015;2015:869746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhuge Y, Liu Y, Xie W, Zou X, Xu J, Wang J; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology Committee of Hepatobiliary Disease. Expert consensus on the clinical management of pyrrolizidine alkaloid-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:634-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sue MJ, Lee EW, Saab S, McWilliams JP, Durazo F, El-Kabany M, Kaldas F, Busuttil RW, Kee ST. Transjugular Liver Biopsy: Safe Even in Patients With Severe Coagulopathies and Multiple Biopsies. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:e00063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang ZB, Wei LX. [Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a clinical and pathological analysis]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2013;42:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang ZB, Yuan J, Chen W, Wei LX. Transcription factor ERG is a specific and sensitive diagnostic marker for hepatic angiosarcoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3672-3679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park YS, Kim JH, Kim KW, Lee IS, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Sung KB. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma: imaging findings and palliative treatment with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or embolization. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adson MA, Beart RW Jr. Elective hepatic resections. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57:339-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Dematteo RP. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bioulac-Sage P, Laumonier H, Laurent C, Blanc JF, Balabaud C. Benign and malignant vascular tumors of the liver in adults. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:302-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gatta G, Ciccolallo L, Kunkler I, Capocaccia R, Berrino F, Coleman MP, De Angelis R, Faivre J, Lutz JM, Martinez C, Möller T, Sankila R; EUROCARE Working Group. Survival from rare cancer in adults: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ratan R, Patel SR. Chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2016;122:2952-2960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Leowardi C, Hormann Y, Hinz U, Wente MN, Hallscheidt P, Flechtenmacher C, Buchler MW, Friess H, Schwarzbach MH. Ruptured angiosarcoma of the liver treated by emergency catheter-directed embolization. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:804-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |