Published online Nov 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i11.2266

Peer-review started: July 22, 2022

First decision: August 19, 2022

Revised: August 31, 2022

Accepted: October 12, 2022

Article in press: October 12, 2022

Published online: November 15, 2022

Processing time: 116 Days and 8.4 Hours

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) accounts for about 0.25% of colorectal cancer patients. Furthermore, synchronous LCNEC and adenocarcinoma coexistence in the colon is very rare. LCNEC are usually aggressive and have a poor prognosis. Usually, colorectal LCNEC patients complain of abdo

We describe a case of relatively asymptomatic synchronous LCNEC and colon adenocarcinoma. A 62-year-old male patient visited our hospital due to anemia detected by a local health check-up. He did not complain of melena, hematochezia or abdominal pain. Physical examination was unremarkable and his abdomen was soft, nontender and nondistended with no palpable mass. Laboratory tests revealed anemia with hemoglobin 5.1 g/dL. Colonoscopy revealed an ulcerofungating lesion in the ascending colon and about a 1.5 cm-sized large sessile polyp in the sigmoid colon. Endoscopic biopsy of the ascending colon lesion revealed the ulcerofungating mass that was LCNEC and endoscopic mucosal resection at the sigmoid colon lesion showed a large polypoid lesion that was adenocarcinoma. Multiple liver, lung, bone and lymph nodes metastasis was found on chest/abdominal computed tomography and positron emission tomography. The patient was diagnosed with advanced colorectal LCNEC with liver, lung, bone and lymph node metastasis (stage IV) and synchronous colonic adenocarcinoma metastasis. In this case, no specific symptom except anemia was observed despite the multiple metastases. The patient refused systemic chemotherapy and was discharged after transfusion.

We report a case of silent LCNEC of the colon despite the advanced state and synchronous adenocarcinoma.

Core Tip: Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) account for about 0.25% of colorectal cancer patients. Furthermore, LCNEC with synchronous or metachronous adenocarcinoma in the colon has been reported in only a few cases. We report the diagnostic experience of a 62-year-old patient with advanced LCNEC in the colon and synchronous adenocarcinoma metastasis but no definitive symptoms except anemia. We suggest the possibility of an association between the two types of primary colon cancer. Therefore, if a patients diagnosed with LCNEC in the colon, appropriate screening tests are required. Further studies are needed on the pathogenesis of the two primary cancers.

- Citation: Baek HS, Kim SW, Lee ST, Park HS, Seo SY. Silent advanced large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with synchronous adenocarcinoma of the colon: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(11): 2266-2272

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i11/2266.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i11.2266

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) accounts for about 0.25% of colorectal cancer patients[1]. Patients with colorectal LCNEC are usually found to be in an advanced stage with metastasis at the time of diagnosis[2]. Furthermore, LCNEC with synchronous or metachronous adenocarcinoma in the colon has been reported in only a few cases[3,4].

The symptoms of colorectal LCNEC are not different from those of conventional colonic adenocarcinoma. Patients with colorectal LCNEC usually present with abdominal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia or tenesmus. Paraneoplastic and carcinoid syndromes which have resulted from excessive hormone production, may rarely be a clinical presentation[5]. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging are useful for initial diagnosis and staging of disease in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)[6]. However, there are no specific characteristic imaging findings of colorectal LCNEC.

The diagnosis of LCNEC is based on pathologic findings. Histologic features of LCNEC are trabecular growth, organoid nesting, rosettes and perilobular palisading patterns. The tumor cells are generally large and shows moderate to abundant cytoplasm. Nucleoli are often detected and their presence facilitates distinction from small cell carcinoma. Several immunohistochemical markers such as synaptophysin, chromogranin and neural cell adhesion molecule (CD56) are useful for confirmation of neuroendocrine differentiation. However, one positive marker is enough if the staining is clearcut[7].

Here, we report on a case of advanced LCNEC (stage IV) in the colon and synchronous adenocarcinoma metastasis in a patient with no specific symptoms except anemia. This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB No. CUH 2022-07-002), and the patient has signed the informed consent for publication of the case (date of the consent: 2022-04-14).

A 62-year-old male patient visited the hospital for anemia detected by a local health check-up.

He denied abdominal symptoms such as pain, diarrhea and hematochezia.

His medical history was unremarkable.

He was a non-smoker and non-alcohol drinker and had no significant family history.

Physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory tests revealed anemia with hemoglobin 5.1 g/dL and a normal liver function test. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (3.01 ng/mL) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (< 9.0 U/mL) were also within normal limits.

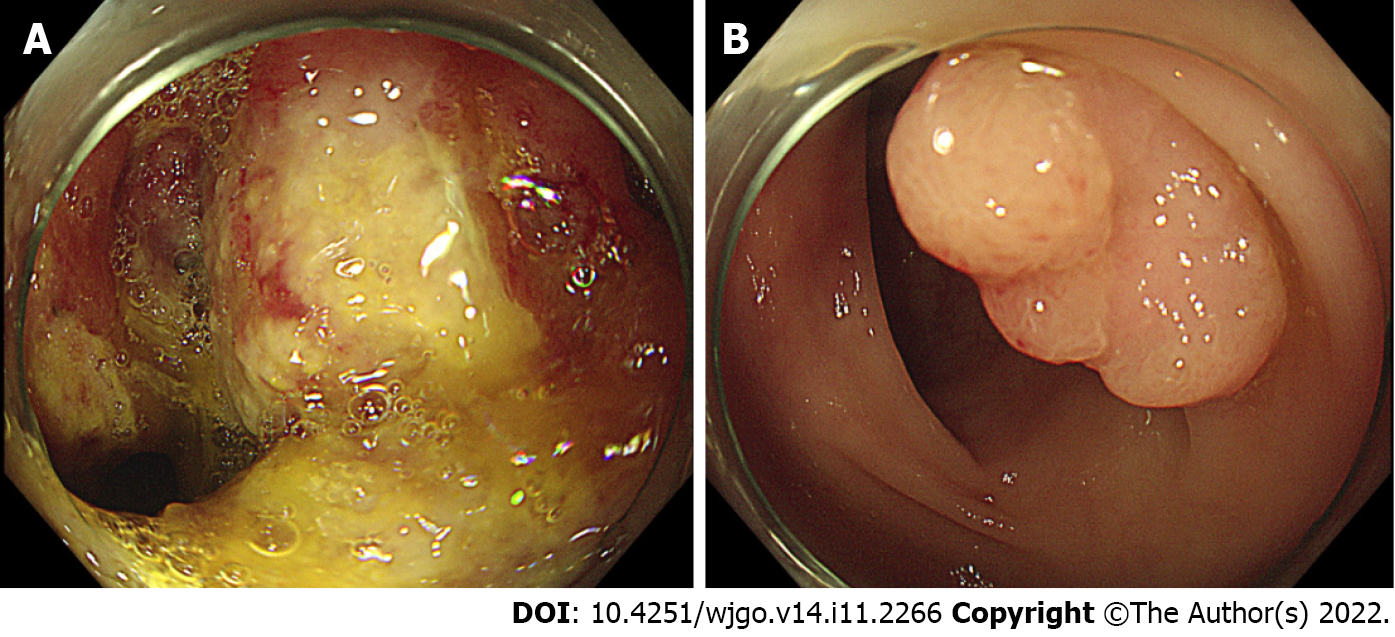

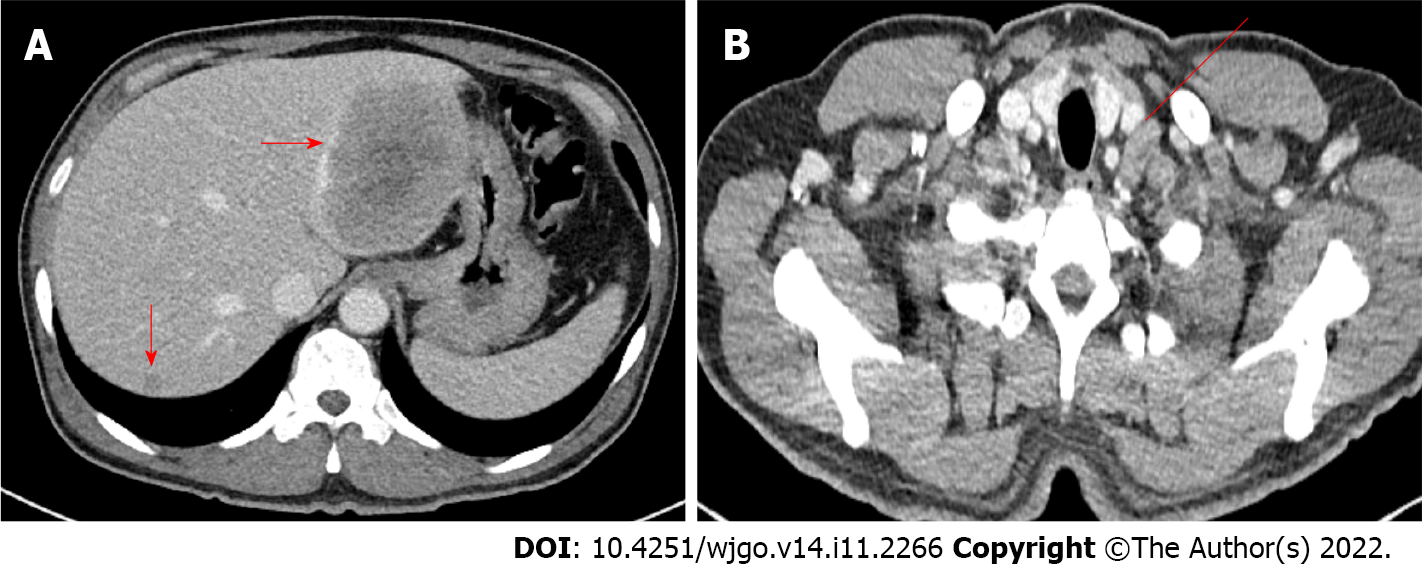

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were performed to find the cause of anemia. Colonoscopy revealed a circumferential ulcerofungating mass in the ascending colon and a biopsy was performed (Figure 1A). Furthermore, about a 1.5 cm-sized large sessile polyp was seen in the sigmoid colon and endoscopic mucosal resection was performed (Figure 1B). Advanced ascending colon cancer was suspected and the patient underwent a chest/abdominopelvic CT. The abdominopelvic CT showed irregular wall thickening over a length of about 10 cm in the ascending colon with regional fat stranding and multiple pericolic lymph node enlargements, thickening and nodularity in the adjacent peritoneum. Moreover, numerous low-density lesions with a maximal 8.7 cm diameter in both the liver lobe (Figure 2A). The chest CT showed left supraclavicular lymph node enlargement (Figure 2B) and a tiny nodule of about 6 mm in the right lung upper lobe.

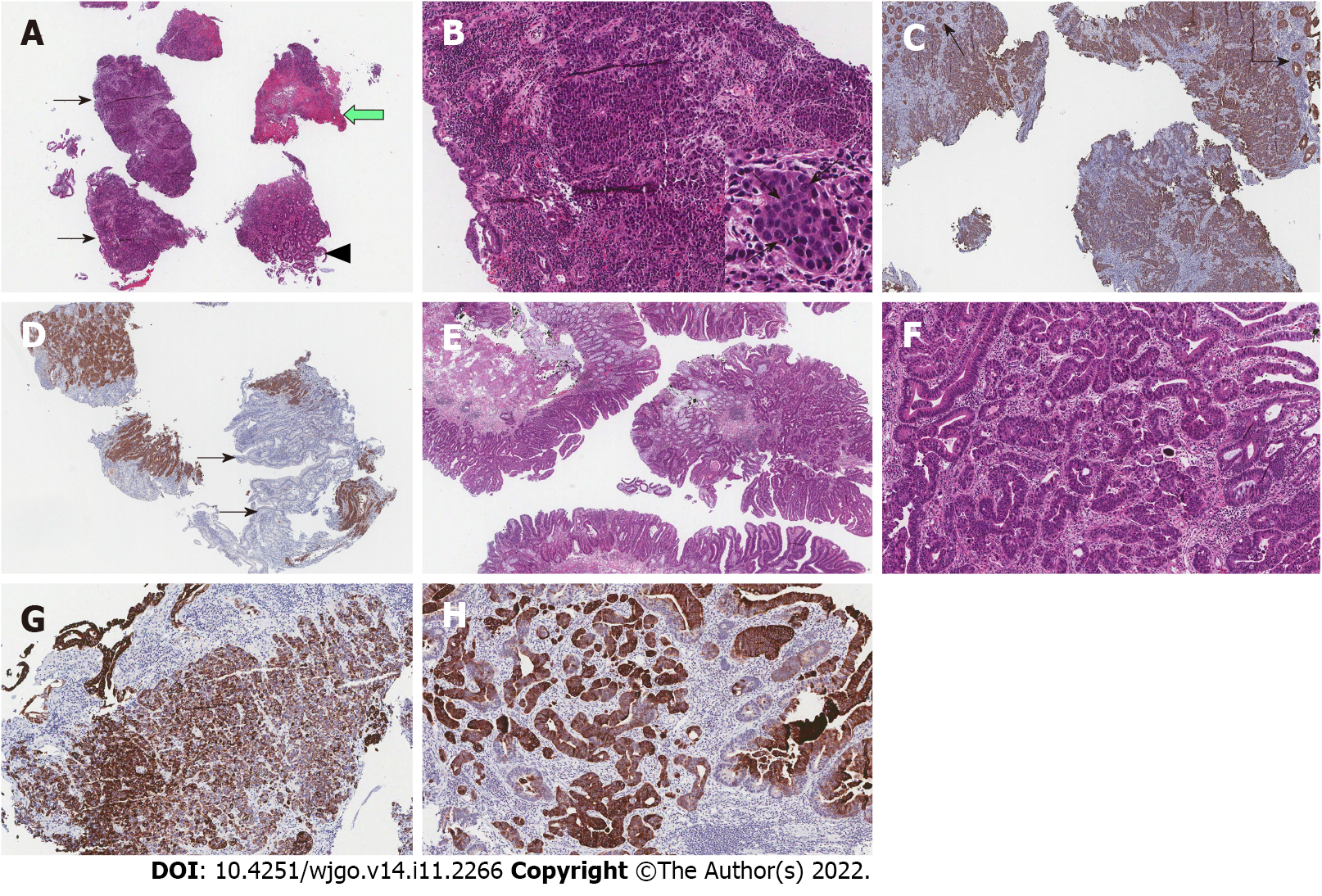

In the pathology report, an ulcerofungating mass in the ascending colon was confirmed as LCNEC, and a large polypoid lesion in the sigmoid colon was confirmed as adenocarcinoma (Figure 3). The LCNEC showed strong immunoreactivity for synaptophysin. The mitotic index was > 30/10HPF and the Ki-67 index was 65.7%, suggesting a poor prognosis. Both the LCNEC and colonic adenocarcinoma showed positive immunohistochemical stain for CK20.

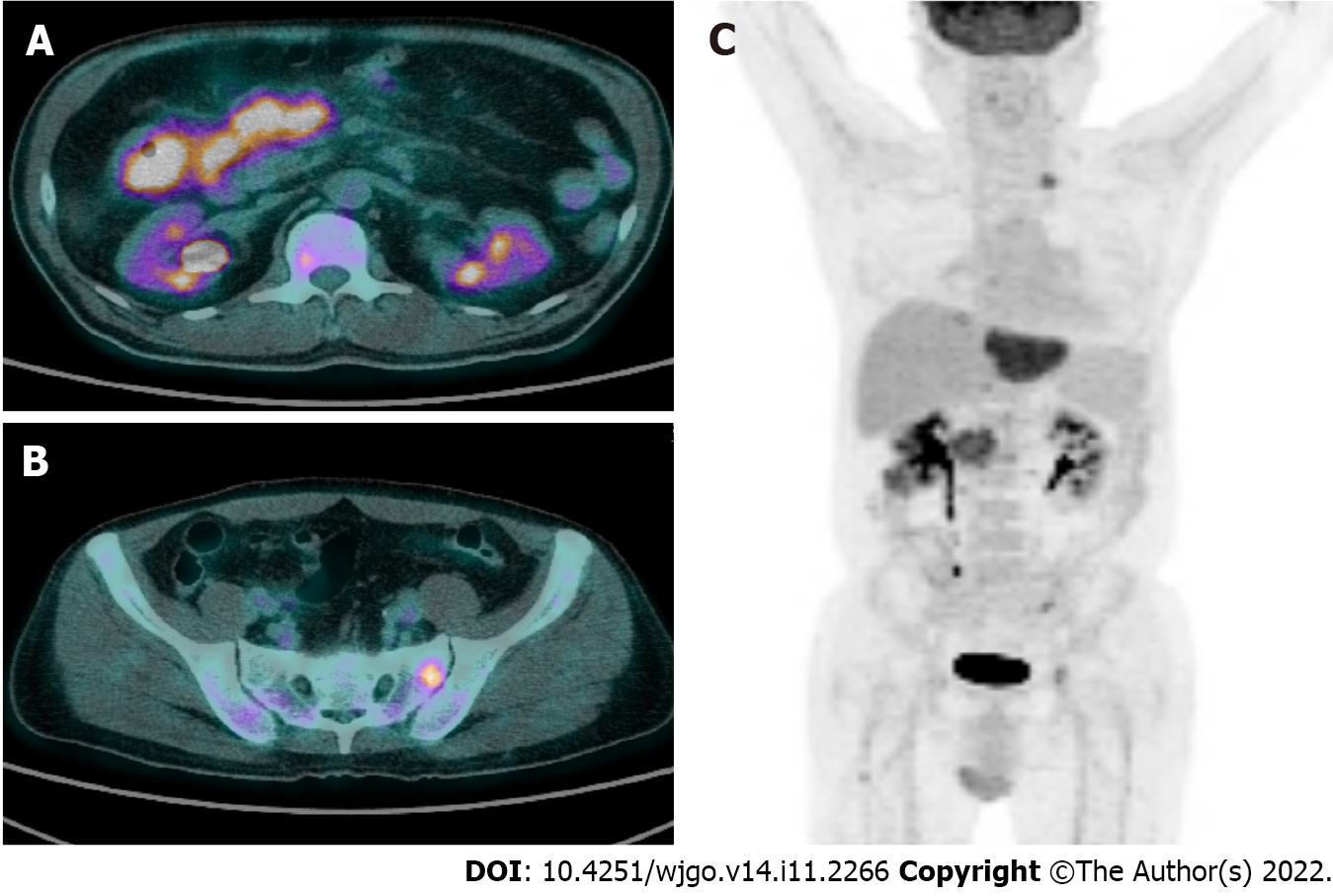

Positron emission tomography revealed abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake at the ascending colon with enlarged lymph nodes at the adjacent mesentery and hematogenous metastasis in the liver, lung, bones, peritoneum and supraclavicular lymph node (Figure 4).

The patient was diagnosed with advanced colorectal LCNEC with liver, lung, bone and lymph nodes metastasis (stage IV) and synchronous colonic adenocarcinoma metastasis.

Systemic chemotherapy was considered but the patient refused treatment and was discharged.

At 3 mo after diagnosis, the patient received the best supportive care and was still alive.

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) occur in the neuroendocrine cells of the gastroenteropancreatic tract and are also known as carcinoids and islet cell tumors. Well-differentiated NENs are classified as NETs G1 or G2. NET G1 can be identical with carcinoid. The term NEC refers to all poorly differentiated NENs. NEC is classified into minor and large cell variants[8]. Most NETs are carcinoids and have a better prognosis than conventional adenocarcinomas.

On the other hand, LCNEC is known to be an aggressive disease and have a poor prognosis[9]. However, in this case, the patient had no abdominal symptoms such as melena, hematochezia or pain despite the advanced LCNEC with multiple metastases. Moreover, no progressive LCNEC-associated symptoms except asymptomatic anemia were observed in this case.

The prognosis of colorectal LCNEC is poor. Colorectal LCNEC is a highly aggressive neoplasm with a high mortality rate[10], and 36% of LCNEC patients had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. The liver is the most involved organ in metastatic disease[11]. In this case, multiple metastatic lesions in the liver, lungs, bones, peritoneum and lymph nodes were noted at the diagnosis.

LCNEC with synchronous or metachronous adenocarcinoma in the colon has been reported only in a few cases. The pathophysiological association between neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma is still unclear. Some suggest a possible association in the pathogenesis of the colorectal NET and adenocarcinoma[12,13]. CK20 is known as a common marker in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Kato et al[13] reported a CK20 positive colonic LCNEC which is accompanied by synchronous colorectal aden

The primary treatment of colorectal LCNEC is surgery if R0 resection is possible[14]. When complete resection is impossible, a debulking procedure and cytoreductive therapy or systemic chemotherapy should be considered[15]. LCNEC is similar to small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC) in histogenesis, biology and clinical behavior. For patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, extrapolation from the treatment paradigms for both non-SCNEC and SCNEC, with chemoradiation and chemotherapy in stage III, and chemotherapy and palliative radiation in stage IV, seems reasonable. Regarding drug choice for systemic chemotherapy, regimens based on efficacy in SCNEC such as etoposide and a platinating agent are preferred[16]. There are no established guidelines for patients diagnosed with LCNEC with synchronous adenocarcinoma of the colon, but chemotherapy can be considered depending on which disease is predominant. In this case, LCNEC was considered a more predominant lesion than adenocarcinoma and a chemotherapy with a combination of cisplatin and etoposide was considered, but the patient refused.

In conclusion, we report on a case of silent LCNEC of the colon despite the advanced state and synchronous adenocarcinoma, suggesting the possibility of an association between the two types of primary colon cancer. In patients diagnosed with LCNEC in the colon, there is a possibility of synch

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu J, China; Liu Z, China; Niu JK, China; Tanabe H, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, Thaler H, Guillem J, Paty P, Cohen AM, Wong WD. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Minocha V, Shuja S, Ali R, Eid E. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum presenting with extensive metastatic disease. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:386379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park JS, Kim L, Kim CH, Bang BW, Lee DH, Jeong S, Shin YW, Kim HG. Synchronous large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the colon. Gut Liver. 2010;4:122-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin KH, Chang NJ, Liou LR, Su MS, Tsao MJ, Huang ML. Metachronous adenocarcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon. Formos J Surg. 2018;51:76. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vilallonga R, Espín Basany E, López Cano M, Landolfi S, Armengol Carrasco M. [Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. A unit's experience over six years]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sahani DV, Bonaffini PA, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Blake MA. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: role of imaging in diagnosis and management. Radiology. 2013;266:38-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | The International Agency for Research on Cancer, Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart (IARC WHO Classification of Tumours) 1st Edition. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004. |

| 8. | Schott M, Klöppel G, Raffel A, Saleh A, Knoefel WT, Scherbaum WA. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Emory RE Jr, Emory TS, Goellner JR, Grant CS, Nagorney DM. Neuroendocrine ampullary tumors: spectrum of disease including the first report of a neuroendocrine carcinoma of non-small cell type. Surgery. 1994;115:762-766. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Staren ED, Gould VE, Jansson DS, Hyser M, Gooch GT, Economou SG. Neuroendocrine differentiation in "poorly differentiated" colon carcinomas. Am Surg. 1990;56:412-419. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Aytac E, Ozdemir Y, Ozuner G. Long term outcomes of neuroendocrine carcinomas (high-grade neuroendocrine tumors) of the colon, rectum, and anal canal. J Visc Surg. 2014;151:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lipka S, Hurtado-Cordovi J, Avezbakiyev B, Freedman L, Clark T, Rizvon K, Mustacchia P. Synchronous Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma of the Colon: A Link for Common Stem Cell Origin? ACG Case Rep J. 2014;1:96-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kato T, Terashima T, Tomida S, Yamaguchi T, Kawamura H, Kimura N, Ohtani H. Cytokeratin 20-positive large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon. Pathol Int. 2005;55:524-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pascarella MR, McCloskey D, Jenab-Wolcott J, Vala M, Rovito M, McHugh J. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon: A rare and aggressive tumor. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2:250-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arnold R. Endocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Introduction: definition, historical aspects, classification, staging, prognosis and therapeutic options. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:491-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Glisson BS, Moran CA. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: controversies in diagnosis and treatment. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:1122-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |