Published online Jul 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i7.706

Peer-review started: March 11, 2021

First decision: April 19, 2021

Revised: April 19, 2021

Accepted: June 4, 2021

Article in press: June 4, 2021

Published online: July 15, 2021

Processing time: 121 Days and 2.5 Hours

Experience in minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (DGISTs) is accumulating, but there is no consensus on the choice of surgical method.

To summarize the technique and feasibility of robotic resection of DGISTs.

The perioperative and demographic outcomes of a consecutive series of patients who underwent robotic resection and open resection of DGISTs between May 1, 2010 and May 1, 2020 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into the open surgery group and the robotic surgery group. Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) or limited resection was performed based on the location of the tumour and the distance between the tumour and duodenal papilla. Age, sex, tumour location, tumour size, operation time (OT), estimated blood loss (EBL), postoperative hospital stay (PHS), tumour mitosis, postoperative risk classification, postoperative recurrence and recurrence-free survival were compared between the two groups.

Of the 28 patients included, 19 were male and 9 were female aged 51.3 ± 13.1 years. Limited resection was performed in 17 patients, and PD was performed in 11 patients. Eleven patients underwent open surgery, and 17 patients underwent robotic surgery. Two patients in the robotic surgery group underwent conversion to open surgery. All the tumours were R0 resected, and there was no significant difference in age, sex, tumour size, operation mode, PHS, tumour mitosis, incidence of postoperative complications, risk classification, postoperative targeted drug therapy or postoperative recurrence between the two groups (P > 0.05). OT and EBL in the robotic group were significantly different to those in the open surgery group (P < 0.05). All the patients survived during the follow-up period, and 4 patients had recurrence and metastasis. No significant difference in recurrence-free survival was noted between the open surgery group and the robotic surgery group (P > 0.05).

Robotic resection is safe and feasible for patients with DGISTs, and its therapeutic effect is equivalent to open surgery.

Core Tip: Minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (DGISTs) has made rapid progress. More and more cases of DGISTs treated by robotic surgery have been reported. The results of this study suggest that robotic resection of DGISTs is safe and effective, and can be carried out in experienced medical centres.

- Citation: Zhou ZP, Tan XL, Zhao ZM, Gao YX, Song YY, Jia YZ, Li CG. Robotic resection of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumour: Preliminary experience from a single centre. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(7): 706-715

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i7/706.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i7.706

Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (DGISTs) are independent undifferentiated mesenchymal tumours, and account for only 2% to 5% of all gastrointestinal stromal tumours[1-5]. Surgical resection is the most effective treatment for DGISTs[6,7]. Nevertheless, due to the special location of the duodenum at the junction of the biliary tract, pancreas and gastrointestinal tract, and its complex anatomical and physiological functions, there is no consensus on the choice of surgical technique[8].

Resection methods for DGISTs include limited resection and pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), which should be determined according to the location of the tumour, the relationship between the tumour and the duodenal papilla, and whether the tumour invades the surrounding tissues. The indications for minimally invasive surgery, such as laparoscopic and robotic resection, have been expanding the treatment for DGISTs in recent years[9,10]. Laparoscopic or robotic resection can be performed according to the location and size of the tumour in an experienced medical centre.

The primary purpose of resection is to achieve minimal complications and avoid complicated operations or multiple organ resections[11]. Our surgical team has performed more than 4000 robotic hepatopancreatobiliary procedures in the past ten years. The purpose of this study was to analyze and compare the effect of robotic resection and open surgery in the treatment of DGISTs. This study also provides a reference for scientific and reasonable selection of the surgical treatment for DGISTs.

The clinical data of 28 consecutive patients who underwent surgical resection of DGISTs between May 1, 2010 and May 1, 2020 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into the open surgery group and the robotic surgery group. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chinese PLA General Hospital.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Single or multiple tumours limited to the duodenum; (2) R0 resection confirmed by postoperative pathology; and (3) No general medical conditions that contraindicated anaesthesia and surgery. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Liver or other abdominal organ metastasis; (2) Invasion of the portal vein or portal vein tumour thrombus, and (3) Targeted therapy before surgery.

Duodenal endoscopic ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans were performed as routine diagnostic procedures before surgery.

Baseline demographics and perioperative and pathology data were obtained from the electronic medical records. Clinical outcomes, including operation time (OT), estimated blood loss (EBL), postoperative complications (POPC), and postoperative hospital stay (PHS), were analyzed retrospectively.

POPC included postoperative pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying (DGE), postoperative haemorrhage and bacteraemia. All complications were documented clearly and graded according to the International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery grading system[12]. The recurrence risk assessment system for primary DGISTs after complete resection was according to the modified National Institutes of Health classification system (2008)[13].

All robotic operations in this study were performed by a single team of surgeons using the Da Vinci Si Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States). PD or limited resection was performed based on the location of the tumour and the distance between the tumour and duodenal papilla. The anastomotic method of pancreaticojejunostomy and choledochojejunostomy used in open or robotic PD (RPD) surgery was the same. Five ports were placed in the robotic resection. After docking, dissection and mobilization of the duodenum were performed using a coagulation hook or an ultrasonic scalpel. Intraoperative ultrasound was used to locate the tumour and determine the boundary of the DGIST during surgery.

All patients were followed up for 1 mo after discharge and then at 6-mo intervals thereafter. According to the results of the postoperative recurrence risk assessment, moderate- to high-grade patients were recommended to take imatinib (Novartis Pharma Schweiz AG, Switzerland) at 400 mg/d for 3 years[14].

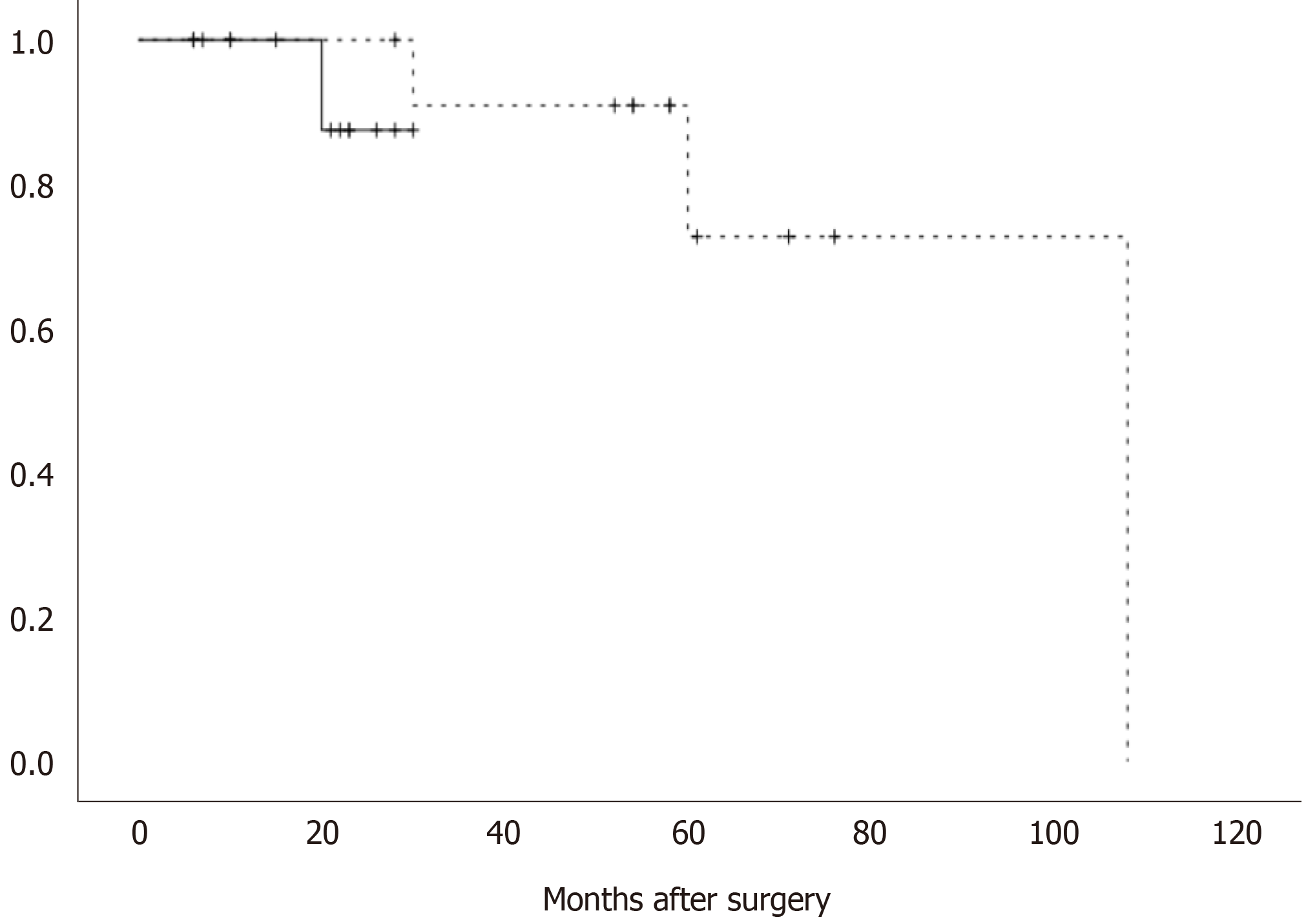

Continuous data are presented as the mean ± SD 1. The Student’s t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables between groups, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and a comparison of OS between subgroups was analyzed using the log-rank test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistical software, version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 19 male and 9 female patients with a mean age of 51 years. The most common tumour site was the descending section of the duodenum (16, 57%) followed by the horizontal section (9, 32%), the bulb section (2, 7%), and the ascending section (1, 4%). Limited resection was performed in 17 patients, and PD was performed in 11 patients. Eleven patients underwent open surgery, and 17 patients underwent robotic surgery. Two patients in the robotic surgery group underwent conversion to open surgery. Nine patients received imatinib after surgery, and 4 patients had postoperative recurrence and metastasis. All the tumours were DGISTs on final histopathological examination, and were R0 resected.

| Clinicopathologic features | Value (%) |

| Mean age (range), yr | 51.3 ± 13.1 (30-84) |

| Sex, male/female | |

| Male | 19 (68) |

| Female | 9 (32) |

| Tumor location | |

| Bulb | 2 (7) |

| Descending section | 16 (57) |

| Horizontal section | 9 (32) |

| Ascending section | 1 (4) |

| Surgical technique | |

| Open surgery | 13 (46) |

| Robotic surgery | 15 (54) |

| Types of resection | |

| Limited resection | 17 (61) |

| PD | 11 (39) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| ≤ 2 | 2 (7) |

| 2-5 | 17 (61) |

| 5-10 | 7 (25) |

| > 10 | 2 (7) |

| Risk assessment (NIH 2008) | |

| Low | 19 (68) |

| Medium | 5 (18) |

| High | 4 (14) |

| Resection margin status | |

| R0 | 28 (100) |

| R1 | 0 |

| Postoperative targeted drug therapy | |

| Yes | 9 (32) |

| No | 19 (68) |

| Postoperative recurrence and metastasis | |

| Yes | 4 (14) |

| No | 24 (86) |

Of the 28 patients, 13 underwent open surgery, and 15 underwent robotic surgery. No significant differences in age, sex, tumour size, operation mode, PHS, tumour mitosis, incidence of POPC, risk classification, postoperative targeted drug therapy or postoperative recurrence were observed between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2). OT and EBL in the robotic surgery group were significantly different compared with those in the open surgery group (P < 0.05). Complications included POPE in 9 cases, DGE in 5 cases and abdominal haemorrhage in 2 cases, and all the patients were cured after conservative treatment.

| No. of patients | P value | ||

| Open | Robotic | ||

| Total patients | 13 | 15 | |

| Age | 0.718 | ||

| ≥ 50 yr | 8 | 8 | |

| < 50 yr | 5 | 7 | |

| Sex | 0.689 | ||

| Male | 8 | 11 | |

| Female | 5 | 4 | |

| Tumor size | 0.255 | ||

| < 5 cm | 5 | 10 | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 8 | 5 | |

| Surgical technique | 0.700 | ||

| Limited resection | 7 | 10 | |

| PD | 6 | 5 | |

| OT (min) | 0.029 | ||

| mean ± SD 1 | 207.7 ± 63.1 | 156.0 ± 55.4 | |

| EBL (mL) | 0.01 | ||

| mean ± SD 1 | 340.0 ± 401.8 | 62.3 ± 34.9 | |

| PHS (d) | 0.294 | ||

| mean ± SD 1 | 16 ± 9.4 | 15.7 ± 13.4 | |

| Mitotic count (/50 HPF) | 1.000 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 12 | 14 | |

| > 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Risk assessment | 0.072 | ||

| Low | 6 | 13 | |

| Medium | 4 | 1 | |

| High | 3 | 1 | |

| POPC | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 7 | |

| No | 6 | 8 | |

| Postoperative targeted therapy | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 5 | |

| No | 9 | 10 | |

| Recurrence/metastasis | 0.311 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 1 | |

| No | 10 | 14 | |

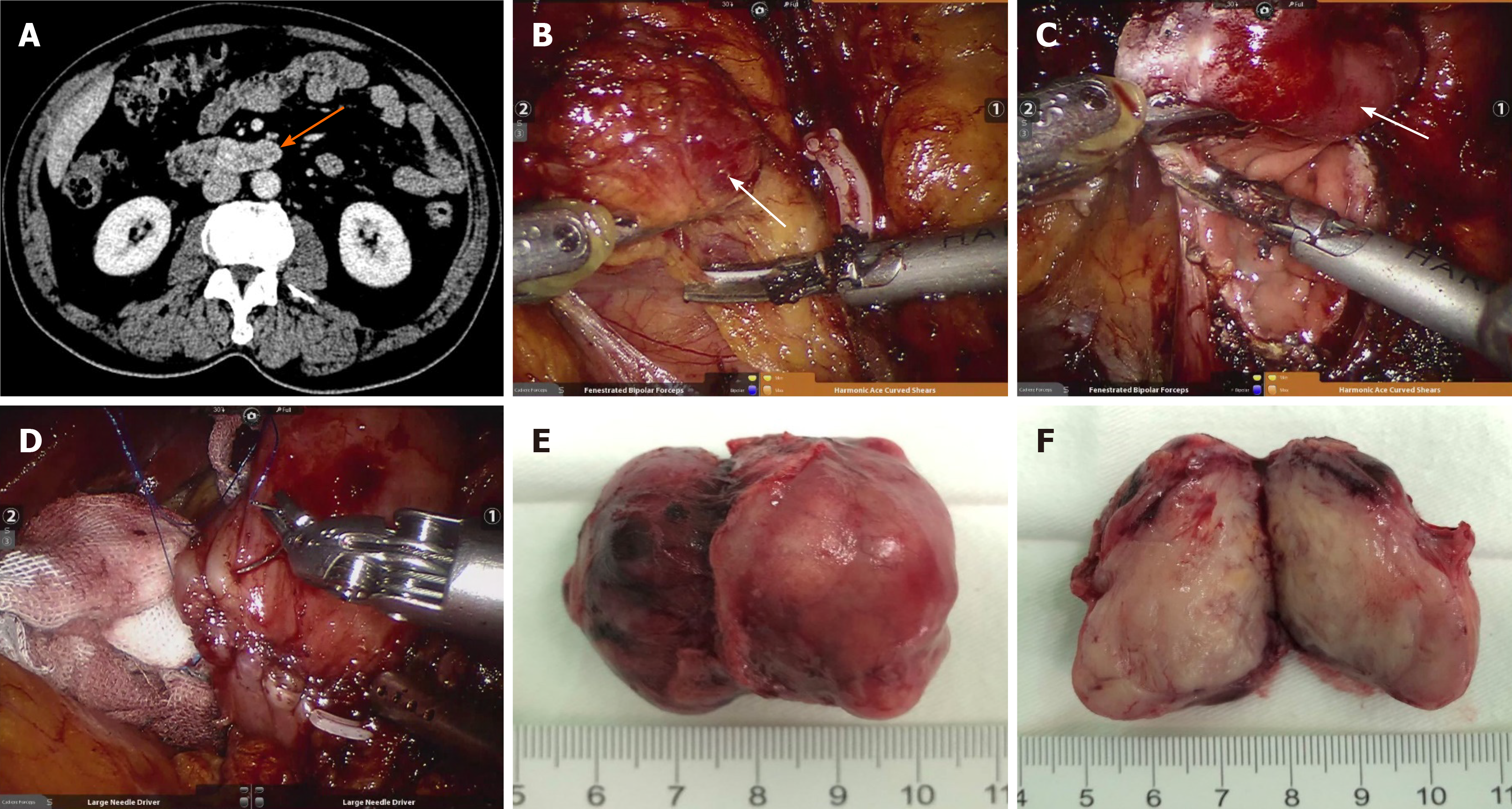

In the robotic surgery group, 15 patients completed the operation, and 2 patients were converted to open surgery because the tumour was located at the horizontal segment of the duodenum and the surrounding inflammatory adhesion was too serious. Limited resection was performed in 10 cases, and PD was performed in 5 cases. As shown in Figure 1, the surgeons performed duodenal dissection, tumour resection, duodenal repair and duodenojejunostomy using a robotic surgery system.

All 28 patients survived during the follow-up period. The postoperative pathology showed that the recurrence risk in 5 patients was medium grade, and was high grade in another 4 patients. All 9 patients were treated with imatinib, and 4 patients developed recurrence and metastasis. Among the patients with recurrence and metastasis, liver metastasis occurred in 3 cases, and mesocolon metastasis occurred in 1 case. All of these tumours were resected (Table 3). Figure 2 shows that there was no significant difference in recurrence-free survival between the open surgery group and the robotic surgery group (P > 0.05).

| Patient, No./sex/age, yr | Tumor location | Operation | Recurrent time (mo) | Recurrent location | Risk of disease progression |

| 1/M/75 | Descending section | RPD | 21 | Liver | Medium |

| 2/M/61 | Horizontal section | PD | 36 | Mesocolon | High |

| 3/M/50 | Descending section | PD | 108 | Liver | Medium |

| 4/M/56 | Descending section | PD | 60 | Liver | Medium |

The incidence of DGIST is low, and patients are typically asymptomatic. Surgical resection can achieve radical cure, but there is no consensus on the choice of surgical technique. The size of the tumour varies from patient to patient when the diagnosis is confirmed, and most tumours are located in the descending section of the duodenum[15]. Some tumours are close to the nipple and often invade the whole duodenum and pancreas. All of the above factors affect the choice of surgical method; therefore, the basis for these selections should be examined. It is helpful to provide a reference for the scientific and reasonable selection of surgical methods for the treatment of DGISTs. The principle of the operation is to completely remove the tumour, ensure a negative margin and intact capsule, and maintain the original anatomical and physiological function of the duodenum as much as possible[16-19].

The location of the tumour and the extent of tumour invasion to surrounding tissues determine the specific surgical method. For DGISTs, limited resection should be adopted as much as possible as PD involves the removal of multiple organs, and the surgical risk and complication rate are high[20,21]. According to the guidelines and consensus of experts, limited resection is recommended for tumours with a distance from the nipple greater than 2 cm. PD is recommended for patients with difficulty in tumour dissection and tumours with a distance from the nipple less than 2 cm that invade the pancreatic head or are closely related to the superior mesenteric vein and superior artery[14,22].

Robotic surgery has more advantages than laparoscopic surgery in duodenal dissection, tumour resection, duodenal repair and duodenojejunostomy. It is easy for surgeons with experience in RPD to dissociate any part of the duodenum. Endoscopic ultrasound is an important method for the diagnosis of GISTs and can confirm the origin and scope of the tumours. Abdominal CT can reveal the tumour location, shape, size, growth mode and its relationship with the gastrointestinal tract[23]. The combination of multiple examinations can improve the diagnostic rate of DGISTs and clarify the lesion site and its invasion to surrounding organs. As duodenoscopy often cannot accurately identify the tumour location during surgery, we routinely use intraoperative ultrasound combined with preoperative imaging examination to determine the tumour location during surgery[24]. All the tumours in this study were finally identified and located during robotic resection.

Our results revealed significant differences in the mean OT and intraoperative blood loss between the robotic surgery group and the open surgery group. These findings suggested that robotic surgery not only has the same therapeutic effect as traditional open surgery but also has the advantages of a shorter OT, less intraoperative bleeding and smaller surgical incision. Such robotic operations are recommended to treat DGISTs in medical centres with robotic surgery facilities and corresponding experience.

Tumour rupture should be avoided as much as possible during DGIST resection because it is a high-risk factor for postoperative recurrence and metastasis[3,5,7-11]. Tumours located in the horizontal segment of the duodenum are often closely related to the superior mesenteric vein and superior artery. If inflammation and adhesion around the tumour are serious, it is difficult to dissociate the duodenum. In the present study, two patients who underwent robotic surgery were converted to open surgery. Avoiding tumour rupture is the most important factor for surgeons making decisions regarding surgical conversion.

Postoperative DGE, abdominal bleeding, POPE and bacteraemia are common complications in both robotic surgery and open surgery for DGISTs. The treatment principle of POPC in the two surgical methods is the same as that of conventional gastrointestinal surgery and PD[6,16,17]. Patients with a medium and high risk of recurrence were recommended to take imatinib for 3 years to avoid tumour recurrence[14]. In this group of patients, one patient had liver metastasis 2 years after drug withdrawal, and another patient developed liver metastasis 9 years after surgery. This finding indicates whether the oral targeted drug time should be extended after surgery.

The limitation of this study is that the sample size was too small, and a large amount of case data should be accumulated in future research. In summary, our study suggests that robotic resection of DGISTs is safe and feasible and has the same therapeutic effect as traditional open surgery. Such surgery can be performed in suitable medical centres, which can reduce surgical trauma, accelerate postoperative rehabilitation, and provide more options for surgical treatment.

In conclusion, robotic resection is safe and feasible for patients with DGISTs, and its therapeutic effect is equivalent to open surgery.

Surgical resection can achieve radical cure of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (DGISTs); however, there is no consensus on the choice of surgical technique.

The application of robotic surgery in the treatment of DGISTs.

Summarize the experience of a single center treating DGISTs by robotic resection.

The perioperative and demographic outcomes of a consecutive series of patients who underwent robotic surgery to treat DGISTs were retrospectively analyzed.

Of the 28 patients enrolled, 11 patients underwent open surgery, and 17 patients underwent robotic surgery. All the tumours were R0 resected, and there were no significant differences in age, sex, tumour size, operation mode, postoperative hospital stay, tumour mitosis, incidence of postoperative complications, risk classification, postoperative targeted drug therapy or postoperative recurrence between the two groups (P > 0.05). Operation time and estimated blood loss in the robotic group were significantly different to those in the open surgery group (P < 0.05). No significant difference in recurrence-free survival was noted between the open surgery group and the robotic surgery group (P > 0.05).

Robotic resection is safe and feasible for patients with DGISTs, and its therapeutic effect is equivalent to open surgery.

Accumulation of experience in the treatment of DGISTs using robotic resection is required.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dik VK, Trarbach T S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Lee SJ, Song KB, Lee YJ, Kim SC, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Shin SH, Kwon JW, Hwang SH, Ma CH, Park GS, Park YJ, Park KM. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Optimal Surgical Treatment of Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:270-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee SY, Goh BK, Sadot E, Rajeev R, Balachandran VP, Gönen M, Kingham TP, Allen PJ, D'Angelica MI, Jarnagin WR, Coit D, Wong WK, Ong HS, Chung AY, DeMatteo RP. Surgical Strategy and Outcomes in Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:202-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lv A, Qian H, Qiu H, Wu J, Li Y, Li Z, Hao C. Organ-preserving surgery for locally advanced duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor after neoadjuvant treatment. Biosci Trends. 2017;11:483-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang S, Tian Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, Zheng C, Wang C. Clinicopathological Characteristics, Surgical Treatments, and Survival Outcomes of Patients with Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Dig Surg. 2019;36:206-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim YJ, Lee WJ, Won CH, Choi JH, Lee MW. Metastatic Cutaneous Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: A Possible Clue to Multiple Metastases. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shen Z, Chen P, Du N, Khadaroo PA, Mao D, Gu L. Pancreaticoduodenectomy vs limited resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen P, Song T, Wang X, Zhou H, Zhang T, Wu Q, Kong D, Cui Y, Li H, Li Q. Surgery for Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Single-Center Experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:3167-3176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cavallaro G, Polistena A, D'Ermo G, Pedullà G, De Toma G. Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on clinical and surgical aspects. Int J Surg. 2012;10:463-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marano A, Allisiardi F, Perino E, Pellegrino L, Geretto P, Borghi F. Robotic Treatment for Large Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1101-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koh YX, Goh BKP. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ginori A, Scaramuzzino F, Marsili S, Tripodi S. Late hepatic metastasis from a duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (29 years after surgery): report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:317-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3041] [Cited by in RCA: 2957] [Article Influence: 369.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 13. | Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, Nilsson B, Cirilli C, Braconi C, Bordoni A, Magnusson MK, Linke Z, Sufliarsky J, Federico M, Jonasson JG, Dei Tos AP, Rutkowski P. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Marti JH, Grosser N, Thomson DM. Tube leukocyte adherence inhibition assay for the detection of anti-tumour immunity. II. Monocyte reacts with tumour antigen via cytophilic anti-tumour antibody. Int J Cancer. 1976;18:48-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 72.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 16. | Colombo C, Ronellenfitsch U, Yuxin Z, Rutkowski P, Miceli R, Bylina E, Hohenberger P, Raut CP, Gronchi A. Clinical, pathological and surgical characteristics of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor and their influence on survival: a multi-center study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3361-3367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang H, Liu Q. Prognostic Indicators for Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Review. Transl Oncol. 2020;13:100812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marano L, Boccardi V, Marrelli D, Roviello F. Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: From clinicopathological features to surgical outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:814-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Uppal A, Wang M, Fischer T, Goldfarb M. Duodenal GI stromal tumors: Is radical resection necessary? J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:940-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Crown A, Biehl TR, Rocha FG. Local resection for duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg. 2016;211:867-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu Z, Zheng G, Liu J, Liu S, Xu G, Wang Q, Guo M, Lian X, Zhang H, Feng F. Clinicopathological features, surgical strategy and prognosis of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a series of 300 patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shen C, Chen H, Yin Y, Chen J, Han L, Zhang B, Chen Z. Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinicopathological characteristics, surgery, and long-term outcome. BMC Surg. 2015;15:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cai PQ, Lv XF, Tian L, Luo ZP, Mitteer RA Jr, Fan Y, Wu YP. CT Characterization of Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:988-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gaspar JP, Stelow EB, Wang AY. Approach to the endoscopic resection of duodenal lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:600-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |