Published online Dec 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i12.2203

Peer-review started: March 23, 2021

First decision: May 3, 2021

Revised: May 30, 2021

Accepted: October 31, 2021

Article in press: October 31, 2021

Published online: December 15, 2021

Processing time: 266 Days and 6 Hours

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is the second most common primary liver cancer and is characterized by an aggressive behavior and a dismal prognosis. Radical surgical resection represents the only potentially curative treatment. Despite the increasing acceptance of laparoscopic liver resection for surgical treatment of malignant liver diseases, its use for ICC is not commonly performed. In fact, to achieve surgical free margins a major resection and/or vascular and/or biliary reconstructions is often needed, as well as an associated lymph node dissection.

To review and summarize the current evidences on the minimally invasive resection of ICC.

A systematic review of the literature based on the criteria predetermined by the investigators was performed from the 1st of January 2009 up to the 1st of January 2021 in 4 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Cochrane databases). All retrospective and prospective studies reporting on the comparative outcomes of open vs minimally invasive treatment of ICC were included. An evaluation of manuscripts quality was achieved using Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies criteria and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

After a systematic search 9 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Among the all 3012 included patients, 2450 were operated by an open approach and 562 by a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approach. Baseline characteristics, tumor characteristics, surgical outcomes and oncological outcomes were collected and analyzed, highlighting values with a statistical significant difference between patients treated with open or laparoscopic approach. Shorter hospital stay and lower intraoperative blood losses were reported by some Authors in minimally invasive surgery, on the contrary, in the open group there was a higher number of lymphadenectomies and a higher percentage of major hepatectomies.

Minimally invasive resection of ICC has some short-term benefits and it is safe and feasible only in selected centers with a high experience in laparoscopic approach for liver surgery. Minimally invasive surgery, actually, was considered mainly in patients with a tumor with a diameter < 5 cm, without invasion of main biliary duct or main vessel and no vascular or biliary reconstructions were planned. Further studies are needed to elucidate its impact on long term oncologic outcomes.

Core Tip: Reports on the minimally invasive treatment of intrahepatic cholanciocarcinoma are scanty and no clear evidences on the feasibility, safety and oncological results are currently available. The aim of our study is to review and summarize the current evidences on the topic and to compare the short and long term outcomes to those of open surgical resection.

- Citation: Patrone R, Izzo F, Palaia R, Granata V, Nasti G, Ottaiano A, Pasta G, Belli A. Minimally invasive surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(12): 2203-2215

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i12/2203.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i12.2203

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is a rare gastrointestinal malignancy arising from epithelial cells of the intrahepatic bile ducts (cholangiocytes) and accounts for 10%-15% of all primary liver cancers[1]. ICC is the second most common primary liver cancer after hepatocellular carcinoma and is characterized by an aggressive behavior and a dismal prognosis[2]. Its occurrence has progressively raised worldwide during the past decades with a reported increase of more than 165% in its incidence in the last 35 years in the western world population[3,4] (from 0.49 per 100000 in 1995 to 1.49 per 100000 in 2014 in the United States)[5]. Radical surgical resection represents the only potentially curative treatment of ICC. Regrettably, less than 40% of patients are eligible for surgery mainly due to late advanced disease at the time of diagnosis[6]. Considering the lack of effective and established chemotherapeutic options, both in adjuvant and first line setting, even after radical resection 50% to 60% of patients will experience a recurrence[7], with a 5 years overall survival of ICC reported to vary from 15% to 40 % after liver resection[8], strongly depending on the presence of poor prognostic factors such as lymph nodes involvement, multiple nodules and vascular invasion[9]. Despite the fact that minimally invasive approach to primary and metastatic liver cancer is becoming a routine approach in selected patients, showing improved perioperative outcomes and similar oncological outcomes than open surgery for the treatment of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[10,11] and colorectal liver metastases (CRLM)[12,13], reports on the minimally invasive treatment of ICC are scanty and no clear evidences on the feasibility, safety and oncological results are currently available. In a recent systematic review on laparoscopic liver resection, published in 2016, among 9527 patients only 116 underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy for ICC[14]. These data strongly reflect the reluctance, even in highly specialized centers, to embrace the minimally invasive approach for ICC. This is probably connected to the necessity of performing loco-regional lymphadenectomy, which is a technically demanding procedure to perform by a minimally invasive approach, and it is also due to the fact that ICC treatment often requires major hepatectomies or vascular and/or biliary reconstruction to achieve a R0 resection. In addition, the Southampton guidelines consensus, despite strongly supporting the adoption of the laparoscopic approach for both HCC and CRLM, did not address the role of minimally invasive approach for the surgical management of ICC[15]. Therefore, updates on the current evidences on the minimally invasive treatment of ICC are urgently needed. The aim of this study is to review and summarize the current evidences on the topic.

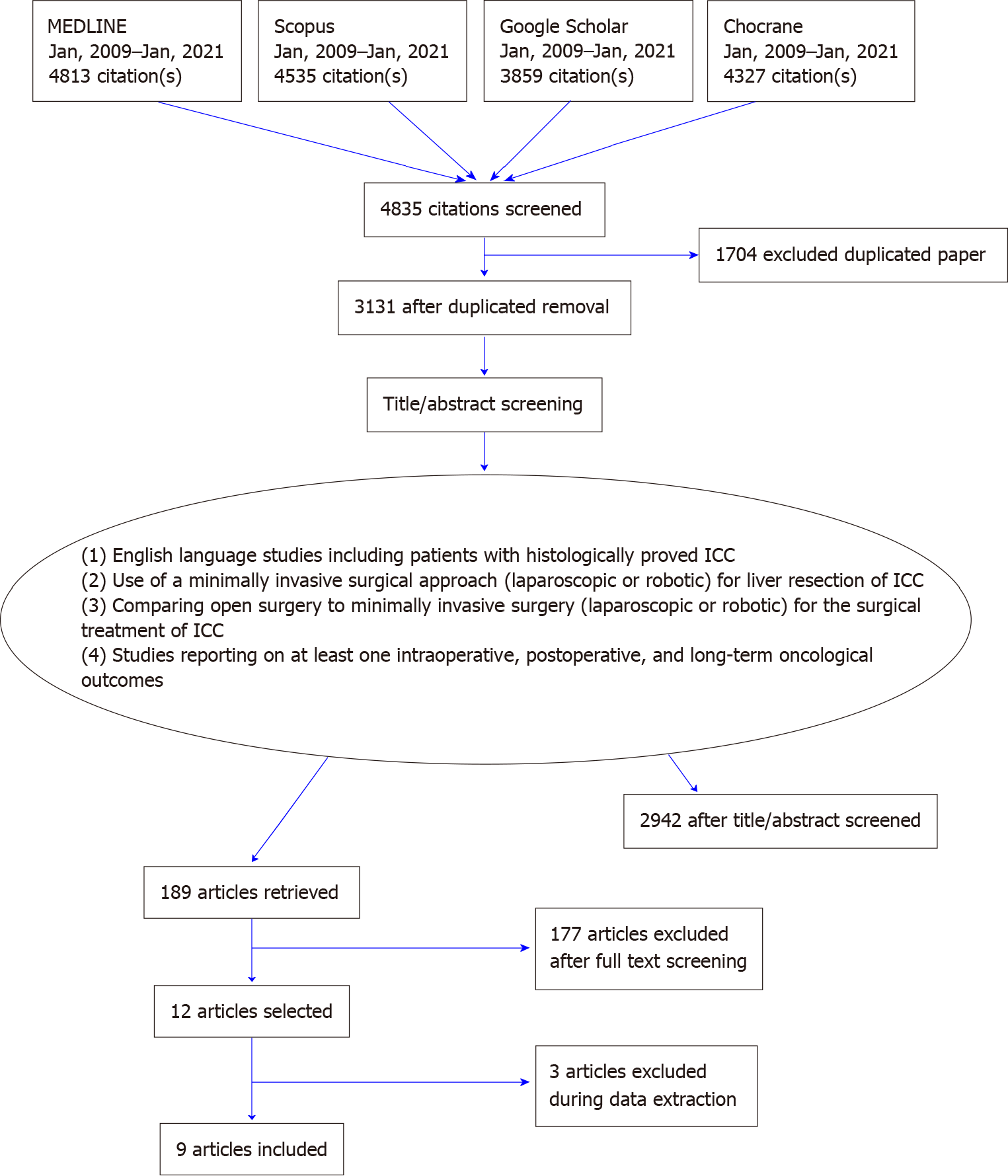

The present study was accomplished in accordance with the preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[16]. A systematic review of the literature, based on criteria predetermined by the investigators, was independently performed by two authors (B.A. and P.R.) from the 1st of January 2009 up to the 1st of January 2021 in 4 databases (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Cochrane databases) in order to maximize articles capturing. Discrepancy in data collection, synthesis and analysis were solved by consensus of all authors. All retrospective and prospective studies reporting on the comparative outcomes of open vs minimally invasive treatment of ICC were included. Search terms included: "cholangiocarcinoma", "intrahepatic", "laparoscopic", "surgery", "minimally invasive", "robotic surgery" "biliary neoplasm", "liver resection" and "hepatectomy".

The following Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied.

(1) English language studies including patients with histologically proved ICC; (2) Use of a minimally invasive surgical approach (laparoscopic or robotic) for liver resection of ICC; (3) Comparing open surgery to minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopic or robotic) for the surgical treatment of ICC; and (4) Studies reporting on at least one intraoperative, postoperative, and long-term oncological outcomes (operative time, intraoperative complications, estimated blood loss, blood transfusion rate, length of stay, R0 resection rate, lymph nodes retrieval, postoperative morbidity and mortality rate, disease free and overall survival rates).

(1) Non-English studies; (2) Animal studies; (3) Non-comparative studies; (4) Abstracts, expert opinions, editorials, meta-analysis, reviews, and letter to the editors; (5) Studies reporting inadequate clinical data; and (6) Studies including mixed pathologies besides ICC; The evaluation of manuscript quality was conducted using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies criteria[17] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[18] to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses because of the non-randomized nature of selected papers.

After systematic search 4835 manuscripts were selected for initial screening. Among them 1704 papers were duplicates and therefore excluded. Based on title, abstract and keywords, the Authors selected and analyzed the full-text version of 189 papers. Main reasons for the exclusion were the absence of patients treated both with laparoscopic and open approach (n = 114) and the inclusion of other types of tumors besides ICC (n = 36). Further causes of exclusion were population treated with palliative intent or case series or absence of specific data on the post-operative outcomes. Two studies selected after full-text analysis were then excluded because more recent studies from the same authors presented additional updated data. This led to the final selection of 9 studies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria[19-27]. The search strategy flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. There were no randomized clinical studies found. All 9 selected papers were retrospective comparative studies and 7 of them were single center series, one a bi-institutional analysis[25] and one was based on data from a national database[23]. Geographical distribution of the selected papers was as follows: Italy and United Kingdom (1), United States (1), Germany (1), Japan (1), Korea (2) and China (3). Characteristics of the included manuscripts and their quality assessment are summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Type of study | LS | OS | NOS | Minors | |||

| Selection | Comparability | Outcame/Exposure | |||||||

| Wu et al[28], 2020 | China | RetS-SC | Case control study | 18 | 25 | *** | * | *** | 17 |

| Haber et al[27], 2020 | Germany | RetS-SC | Case control study | 27 | 31 | *** | * | ** | 16 |

| Kang et al[26], 2020 | Korea | RetS-SC | Propensity score matching | 30 | 61 | *** | ** | *** | 18 |

| Kinoshita et al[24], 2020 | Japan | RetS-SC | Case control study | 15 | 21 | *** | ** | *** | 18 |

| Ratti et al[25], 2020 | United Kingdom-Italy | RetS-TC | Propensity score matching | 104 | 104 | *** | ** | *** | 19 |

| Martin et al[23], 2019 | United States | RetS-DB | Database | 312 | 1997 | ** | * | ** | 15 |

| Zhu et al[22], 2019 | China | RetS-SC | Propensity score matching | 20 | 63 | *** | ** | *** | 19 |

| Wei et al[21], 2017 | China | RetS-SC | Case control study | 30 | 20 | *** | ** | *** | 19 |

| Lee et al[20], 2016 | Korea | RetS-SC | Case control study | 14 | 23 | *** | ** | *** | 20 |

Among all the 3012 included patients 2450 were operated by an open approach and 562 by a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approach.

As regards patients’ baseline characteristics no statistically significant differences were detected in terms of age, sex, body mass index and American Society of Anaesthesiologists score between laparoscopic and open groups in all manuscripts. Eight studies[20-22,24-28] analyzed the presence of at least one comorbidity and no statistical difference was reported between laparoscopic and open group. Detailed data are reported in Table 2.

| Ref. | SA | NP | AGE | ASA | MayorH | Lymphadenectomy | OT | IOBL | CONV. | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | Yes | Number | ||||||||

| Wu et al[28], 2020 | OS | 25 | 61 | 19 | 6 | 13 (52%) | 6 (32%) | 6 | 300 (257-392) | 500 (350-750) | N/A | ||

| LS | 18 | 64 | 15 | 3 | 6 (33%) | 8 (33%) | 6 | 305 (207-390) | 375 (275-500) | 0 | |||

| Haber et al[27], 2020 | OS | 31 | 63 | 1 | 21 | 8 | 1 | 24 (78%) | 29 (94%) | 8 | 282 (112–947) | / | N/A |

| LS | 27 | 69 | 0 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 19 (70%) | 23 (85%) | 8 | 314 (125–439) | / | 2 | |

| Kang et al[26], 2020 | OS | 61 | 68 | / | / | / | / | 53 (88.3%) | 46 (75.4%) | / | 343.2 ± 106.0 | 979.3 ± 864.4 | N/A |

| LS | 30 | 65 | / | / | / | / | 20 (66.7%) | 9 (30%) | / | 375.2 ± 204.0 | 1396.7 ± 2568.9 | 6 | |

| Kinoshita et al[24], 2020 | OS | 21 | 68 | / | / | / | / | 15 | 7 (33%) | 3 | 358 (150-634) | 500 (105-3710) | N/A |

| LS | 15 | 65 | / | / | / | / | 5 | 6 (40%) | 2 | 360 (221-802) | 150 (20-2500) | 0 | |

| Ratti et al[25], 2020 | OS | 209 | 62 | 20 | 58 | 26 | 0 | 38 (36.5%) | 92 (88.5%) | 7 (5–14) | 230 ± 60 | 350 ± 250 | N/A |

| LS | 114 | 60 | 22 | 56 | 26 | 0 | 35 (33.7%) | 87 (83.7%) | 8 (5–11) | 270 ± 65 | 150 ± 100 | 0 | |

| Martin et al[23], 2019 | OS | 1997 | 64 | / | / | / | / | 1338 (67%) | 1210 (61.2%) | / | / | / | N/A |

| LS | 312 | 65 | / | / | / | / | 137 (44%) | 312 (38.5%) | / | / | / | / | |

| Zhu et al[22], 2019 | OS | 63 | 56 | / | / | / | / | 43 (68.3%) | 27 (42.9%) | / | 200 (140–320) | 400 (50–2000) | N/A |

| LS | 20 | 54 | / | / | / | / | 11 (55%) | 8 (40%) | / | 225 (140–400) | 200 (50–1000) | 2 | |

| Wei et al[21], 2017 | OS | 20 | 60.5 | / | / | / | / | 11 (55%) | 11 (55%) | / | 230 (125–420) | 350 (50–1200) | N/A |

| LS | 12 | 61.5 | / | / | / | / | 7 (58.3%) | 4 (33%) | / | 212.5 (60–500) | 350 (30–2000) | 0 | |

| Lee et al[20], 2016 | OS | 23 | 59 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 19 (82.6%) | 15 (65.2%) | 6 (1–16) | 330.0 (140–590) | 625 (250–2500) | N/A |

| LS | 14 | 66 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 7 (50%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (1–12) | 255.0 (140–480) | 325 (10–1500) | 0 | |

Tumor size was reported in all, except one[28], of the analyzed studies and in the study by Martin et al[23] a statistically significant difference between groups was highlighted with a smaller tumor diameter in the laparoscopic group when compared to the open group. Seven of the selected manuscripts[20-22,24-26,28] reported data on preoperative tumors, nodes and metastasis (TNM) staging and CA19.9 values with no differences between groups. CEA preoperative values were analyzed only in four studies[20,24,25,28] and no differences were found. Zhu et al[22], Ratti et al[25] and Kang et al[26] reported a smaller tumor size in the laparoscopic group but this difference was adjusted after propensity score matching. Kinoshita et al[24] found no difference in mean tumor size between the two groups but a higher percentage of patients in the open group had tumors bigger than 3 cm when compared to the laparoscopic group (71% vs 33%). Two[21,22] of the analyzed studies were focused on large (> 3 cm) or multinodular ICCs. All tumors characteristics were resumed in Table 3.

| Ref. | SA | ICUS | HS | HM | 30-d morbidity | 90-d morbidity | mFU | OS | DFS | ||

| R0 | R1 | Grade I-II | Grade III-IV | ||||||||

| Wu et al[28], 2020 | OS | / | 9 (7-15) | / | / | 23 | 2 | 1 | / | 20 | 4 |

| LS | / | 6 (5-12) | / | / | 17 | 1 | 0 | / | 47.1 | 0 | |

| Haber et al[27], 2020 | OS | 1 (0–6) | 12 (5–33) | 23 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 0 | / | / | / |

| LS | 1 (0–81) | 10 (3–94) | 24 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | / | / | / | |

| Kang et al[26], 2020 | OS | / | 18.3 ± 14.7 | / | / | / | 23 | 0 | 16.8 | 81.2 | 42.5 |

| LS | / | 9.8 ± 5.1 | / | / | / | 8 | 0 | 39.2 | 76.7 | 65.6 | |

| Kinoshita et al[24], 2020 | OS | / | / | 20 | 1 | / | 4 | / | / | 36 | 19 |

| LS | / | / | 14 | 1 | / | 2 | / | / | 32 | 24 | |

| Ratti et al[25], 2020 | OS | 4 (3–10) | 6 (3–21) | 99 | 5 | 17 | 8 | 2 | 50 | 47 | 34 |

| LS | 3 (1–5) | 4 (2–10) | 101 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 39 | 46 | 36 | |

| Martin et al[23], 2019 | OS | / | / | 1451 | 546 | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| LS | / | / | 247 | 65 | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Zhu et al[22], 2019 | OS | / | 7 (3–33) | 58 | 5 | 22 | 6 | 0 | 24 | 17 | 32 |

| LS | / | 6 (3–9) | 19 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 21 | 31 | |

| Wei et al[21], 2017 | OS | / | 11 (5–30) | 19 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 32.7 | 27.9 |

| LS | / | 14 (6–23) | 12 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 17.5 | 56.3 | 43.8 | |

| Lee et al[20], 2016 | OS | / | 20 (9–63) | / | / | 1 | 4 | 0 | / | 75.7 | / |

| LS | / | 15 (9–29) | / | / | 0 | 3 | 0 | / | 84.6 | / | |

Operative time was analyzed in 8 out of 9 analyzed studies and only in the study by Zhu et al[22] there was a statistically significant difference in favor of the laparoscopic group. Intraoperative blood loss was reported by 7 studies and a statistically significant lower blood loss was found in the laparoscopic group in 4 of them[20,24,25,28].

With the exception of the national database based study by Martin et al[23], data on postoperative morbidity were reported in all manuscripts and a lower incidence of postoperative complications in the laparoscopic group was found in the studies by Ratti et al[25] and by Haber et al[27].

Laparoscopic approach significantly decreased postoperative hospital stay in four of seven study[25-28]. Days spent in intensive care unit were analyzed only by two studies[25,27] with no differences between open and laparoscopic approach.

As regards the type of liver resection, a statistically significant higher rate of major hepatectomies was reported in the open groups in the studies by Kang et al[26], Martin et al[23] and Lee et al[20]. Accomplishment of lymph nodes dissection was investigated by all analyzed studies and in 3 of them[23,25,26] was reported a higher rate of lymph nodes clearance in the open group but with no difference in nodal status. Six authors reported histopathological margin data with no difference between R0 and R1 in the two surgical approaches[20-23,25,26].

Eight of the selected studies[20-22,24-28] reported comparative data on the oncological outcomes expressed as overall and disease free survival and none of them reported any differences between the open and the laparoscopic group. In the study by Martin et al[23] the authors focused electively on the rate of administration of adjuvant treatments and found no differences related to the surgical approach.

As regards specific variables affecting survival Wu et al[28] identified high preoperative values of CA19.9, high TNM stage and a poor tumor differentiation as independent risk factor for worst overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) while Kang et al[26] identified tumor size, nodularity and perineural invasion as independent factors correlated to lower DFSs.

Kinoshita et al[24], instead, found tumor size (diameter ≥ 3 cm), presence of vascular invasion and a high CA19.9 levels on preoperative exams to be associated with a poorer OS.

Lee et al[20], trying to avoid bias, analyzed OS and RFS in laparoscopic liver resection and open liver resection for all patients by stratifying them by the accomplishment of lymph nodes dissection and found no difference in between groups.

Finally, the pattern of recurrence was investigated only in 3 of the selected manuscripts[20,25,28] with no statistically significant differences between the open and the laparoscopic approach. Detailed data are reported in Table 3.

The current systematic review is focused on the comparative outcomes of open vs minimally invasive resection of ICC. In fact, even if laparoscopy proved to be an effective option for the treatment of both HCC and CRLM, offering the benefit of minimally invasiveness without compromising the oncological outcomes, reports on the operative and oncological outcomes of minimally invasive treatment of ICC are scanty and seldom reported. The uncommon adoption of the laparoscopic or robotic approach for ICC is related to various oncological and technical reasons. First, ICC has a relative low incidence when compared to others liver malignancies and due to its aggressive biological behavior is often diagnosed at an advanced stage not suitable for radical surgery which remains the only potentially curative treatment option[1]. Second, surgery for ICC is often characterized by a high degree of technical difficulty associated with the need of performing an appropriate lymphadenectomy and, especially in centrally located tumors, a vascular or biliary reconstruction as well as a major hepatic resection are often needed to achieve clear surgical margins[29]. These technical issues have probably slowed down the diffusion of ICC as a valid indication for a minimally invasive approach. In fact, major hepatectomies, hepatic hilum lymphadenectomy and biliary reconstructions are technically demanding to perform by a minimally invasive approach. In addition, to safely perform such procedures an extensive learning curve is needed[30] and since now this has been unlikely to be accomplished outside high volume centers with a steady commitment to minimal invasiveness. Notwithstanding that, recently initial data on the comparative outcomes of open vs minimally invasive resection of ICC have been published in the literature. The interest on this topic is, in fact, increasing and the surgical treatment of ICC is becoming one of the latest field of implementation of minimally invasive liver surgery. In particular, all the selected articles for this systematic review have been published in the last 5 years thus reflecting the growing interest on the topic. Nevertheless, despite the accurate search strategy applied, the current systematic review confirmed the paucity of current evidences on the minimally invasive approach for ICC. No randomized comparative studies are currently available and only 9 comparative retrospective studies were retrieved from the systematic search. Although representative of the experience of few highly specialized centers for minimally invasive liver surgery, the analyzed studies proved without doubt the feasibility and safety of the laparoscopic approach to ICC in patients with a tumor diameter < 5 cm, without main biliary duct invasion, without large vascular invasion and in which biliary and vascular reconstructions were not needed. Results from the analyzed studies also confirmed the typical benefit of minimally invasiveness already demonstrated for the laparoscopic treatment of HCC and CRLM, even when dealing with ICC. In fact, several of the analyzed studies reported a benefit of the minimally invasive approach in terms of peri-operative outcomes when compared to the open approach. In details, four studies[20,24,25,28] reported a lower intraoperative blood loss associated with the minimally invasive approach even when dealing with radical lymph nodes clearance and this is probably related to magnified view and the meticulous dissection achievable by laparoscopy. Nevertheless, Kang et al[26] described a higher blood loss rate in the laparoscopic group, but these difference was not statistically significant (P value = 0.393). Furthermore, four of the analyzed studies[25-28] reported a shorter hospital stay associated to the laparoscopic approach, thus confirming the benefit of minimal invasiveness in terms of a faster recovery also in this setting. Finally, despite the relative initial experience, the studies by Ratti et al[25] and Haber et al[27] highlighted a benefit in terms of postoperative morbidity in favor of laparoscopy. However, the reported experiences are mainly focused on mass forming type ICC without vascular and biliary involvement (away from the liver plate) and, as highlighted by the large national database-based study by Martin et al[23], patients operated by laparoscopy had smaller tumor size when compared to those submitted to an open resection. In addition, a statistically significant higher rate of major hepatectomies was reported in the open groups in 3 of the analyzed studies[20,23,26]. This reflects the selection bias, which is to be expected when dealing with the appliance of laparoscopy to a new surgical indication. Indeed, the studies by Zhu et al[22] and Wei et al[21] were focused on large or multinodular ICCs and both confirmed positive results similar to those reported by studies with stricter selection criteria. The benefit of performing a lymphadenectomy for ICC is a debated issue. In fact, up to 40% of resected patients can present with lymph nodes involvement[9] and several authors have highlighted a survival benefit in patients undergoing lymph nodes clearance associated to liver resections when compared to patients who did not[31]. On the contrary, discrepant studies reported no survival benefit and an increase in surgical morbidity associated with lymphadenectomy especially in case of patients with chronic liver disease[32,33]. Nevertheless, lymph nodes clearance for ICC is a crucial strategy for a correct staging of surgically resected patients and can both guides the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy and optimizes clinical risk stratification and prognostic outcomes. This factor is even more significant if we take into account the results of the BILCAP study which demonstrated the survival benefit of adjuvant gemcitabine for biliary tract cancers[34]. Indeed, the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines recommends to perform lymphadenectomy with an optimal cut-off of six retrieved nodes for biliary tract cancers[35]. Is therefore to be expected that regional lymphadenectomy will be implemented in clinical practice and should be performed irrespectively from the open or minimally invasive surgical approach adopted. From the current systematic review, a certain under-employment of regional lymphadenectomy for ICC was highlighted. In fact, a lower rate of lymph nodes dissection in the laparoscopic group was reported in the studies by Kang et al[26] and Ratti et al[25]. These data are confirmed by the National Cancer Database analysis by Martin et al[23] which also highlighted that some form of nodal dissection was performed in only 58% of patients in the whole study cohort. Indeed, the vast majority of the published studies reports the initial experiences of selected high specialized centers and refers to a time preceding the AJCC guidelines diffusion and application. Therefore, after an initial learning curve, a major adherence to the guidelines it is likely to be accomplished. It is also to be expected that the accumulation of experience and the improvement of surgical techniques will probably promote the adoption of the minimally invasive approach for ICC.

In addition, the histopathological margin status is a crucial factor to be considered when comparing the minimally invasive approach to the standard open resection. In fact, an R0 margin represents the most significant predicting factor of oncological outcomes and results from our review show a superimposable rate of negative surgical margin in both approaches. This evidence together with the appropriateness of loco-regional lymphadenectomy and the reduced intraoperative blood loss reported in the majority of the analyzed studies, allow us to consider the laparoscopic approach non inferior to the open one in terms of operative outcomes. Therefore, is not surprising that the minimally invasive approach has been recently extended to the surgical treatment of hilar type cholangiocarcinoma[36] and gallbladder cancer[37,38]. These encouraging pivotal experiences seem to demonstrate the feasibility of minimally invasive surgery in a setting often requiring the completion of a major hepatic resection in association with loco-regional lymphadenectomy and the challenge of biliary reconstructions. It is therefore likely that in the very next future the surgical research in the field of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for biliary cancer will be concentrated on hilar type tumors and on biliary duct resection (with the aid of Indocianyne green guidance) and reconstruction via duct to duct anastomosis or hepatico-jejunostomy. In addition, the implementation of the MIS approach for the surgical treatment of ICC is likely to be promoted by the diffusion of the robotic platforms. In fact, even if it has been demonstrated by the analyzed studies that an appropriate lymphadenectomy can be performed safely and effectively by lapa

In conclusion, the minimally invasive treatment of ICC is currently rarely performed but is rapidly gaining popularity. Currently available data seems to justify the implementation of the minimally invasive approach for ICC by demonstrating its safety and reproducibility and by confirming the well-known advantages of minimally invasiveness in term of perioperative outcomes also in this setting, as already proven for other liver neoplasms. Nevertheless, current evidences are based on few studies with a limited sample size and a short follow-up. In addition, selection criteria for the minimal invasive approach were highly restrictive (small tumors, generally < 3 cm, distant from the hilum and not requiring a biliary reconstruction) when compared to open series and, therefore, at high risk for selection bias. Dedicated study protocols and analysis of national and international registries are urgently needed to clarify the real role of minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of ICC and its impact on the long term oncologic outcomes.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma represents a very aggressive tumor with poor prognosis. Nowadays surgical open approach is still the gold standard treatment but minimally invasive surgery is gaining an important role. No randomized trials are available on this topic in scientific literature.

Our scientific group aim to contribute to the development of the scientific research on hepatobiliary minimally invasive surgery.

Our research had the objective to summarize and review the scientific evidences present in the literature on minimally invasive surgical approach for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

We performed a systematic review of the literature between 01/01/2009 and 01/01/2021. Our research keywords were: "cholangiocarcinoma", "intrahepatic", "laparoscopic", "surgery", "minimally invasive", "robotic surgery" "biliary neoplasm", "liver resection" and "hepatectomy”. We selected only papers comparing open and laparoscopic approach and reporting at least one intraoperative, postoperative or oncological outcomes.

We found 9 papers that fulfilled all inclusion criteria reporting data from 3012 patients with no differences in baseline characteristic. Almost all operative outcomes were in favor of laparoscopic groups (blood losses, operative time, hospital stay, post-operative complications) except for the number of lymphonodes retrieved (higher number of lymphonodes retrieved in the open groups). No statistical differences in oncological outcomes were reported.

Our research demonstrates that very few studies investigated the role of minimally invasive surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Currently available data in the Literature were not consistent enough to consider the laparoscopic approach to ICC as a standard of care but a steady implementation is likely to be realized in the next future.

It is likely that soon the diffusion of robotic surgery and tailored surgery, will promote the diffusion of minimally invasive approach for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and will help elucidating its role and the oncological outcomes.

The authors would like to thank Assunta Zazzaro for her appreciated work and team coordination.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boueroy P, Saengboonmee C S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Khan SA, Tavolari S, Brandi G. Cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Liver Int. 2019;39 Suppl 1:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, Pawlik TM, Gores GJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 1073] [Article Influence: 97.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu L, Tsilimigras DI, Paredes AZ, Mehta R, Hyer JM, Merath K, Sahara K, Bagante F, Beal EW, Shen F, Pawlik TM. Trends in the Incidence, Treatment and Outcomes of Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in the USA: Facility Type is Associated with Margin Status, Use of Lymphadenectomy and Overall Survival. World J Surg. 2019;43:1777-1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Antwi SO, Mousa OY, Patel T. Racial, Ethnic, and Age Disparities in Incidence and Survival of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in the United States; 1995-2014. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17:604-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463-473; discussion 473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hyder O, Hatzaras I, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, Pulitano C, Barroso E, Clary BM, Aldrighetti L, Ferrone CR, Zhu AX, Bauer TW, Walters DM, Groeschl R, Gamblin TC, Marsh JW, Nguyen KT, Turley R, Popescu I, Hubert C, Meyer S, Choti MA, Gigot JF, Mentha G, Pawlik TM. Recurrence after operative management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2013;153:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Doussot A, Groot-Koerkamp B, Wiggers JK, Chou J, Gonen M, DeMatteo RP, Allen PJ, Kingham TP, D'Angelica MI, Jarnagin WR. Outcomes after Resection of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: External Validation and Comparison of Prognostic Models. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:452-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, Pulitano C, Barroso E, Clary BM, Aldrighetti L, Ferrone CR, Zhu AX, Bauer TW, Walters DM, Gamblin TC, Nguyen KT, Turley R, Popescu I, Hubert C, Meyer S, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Gigot JF, Mentha G, Pawlik TM. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3140-3145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Belli A, Fantini C, Cioffi L, D'Agostino A, Belli G. Mils for HCC: the state of art. Updates Surg. 2015;67:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morise Z, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Ratti F, Belli A, Cherqui D, Tanabe M, Wakabayashi G; ILLS-Tokyo Collaborator group. Laparoscopic repeat liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre propensity score-based study. Br J Surg. 2020;107:889-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fretland ÅA, Dagenborg VJ, Bjørnelv GMW, Kazaryan AM, Kristiansen R, Fagerland MW, Hausken J, Tønnessen TI, Abildgaard A, Barkhatov L, Yaqub S, Røsok BI, Bjørnbeth BA, Andersen MH, Flatmark K, Aas E, Edwin B. Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection for Colorectal Liver Metastases: The OSLO-COMET Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:199-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ratti F, Fiorentini G, Cipriani F, Catena M, Paganelli M, Aldrighetti L. Laparoscopic vs Open Surgery for Colorectal Liver Metastases. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:1028-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Briceno J, Wakabayashi G. Comparative Short-term Benefits of Laparoscopic Liver Resection: 9000 Cases and Climbing. Ann Surg. 2016;263:761-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abu Hilal M, Aldrighetti L, Dagher I, Edwin B, Troisi RI, Alikhanov R, Aroori S, Belli G, Besselink M, Briceno J, Gayet B, D'Hondt M, Lesurtel M, Menon K, Lodge P, Rotellar F, Santoyo J, Scatton O, Soubrane O, Sutcliffe R, Van Dam R, White S, Halls MC, Cipriani F, Van der Poel M, Ciria R, Barkhatov L, Gomez-Luque Y, Ocana-Garcia S, Cook A, Buell J, Clavien PA, Dervenis C, Fusai G, Geller D, Lang H, Primrose J, Taylor M, Van Gulik T, Wakabayashi G, Asbun H, Cherqui D. The Southampton Consensus Guidelines for Laparoscopic Liver Surgery: From Indication to Implementation. Ann Surg. 2018;268:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9247] [Cited by in RCA: 8872] [Article Influence: 554.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3743] [Cited by in RCA: 5630] [Article Influence: 255.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 19. | Uy BJ, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY. Laparoscopic liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:272-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee W, Park JH, Kim JY, Kwag SJ, Park T, Jeong SH, Ju YT, Jung EJ, Lee YJ, Hong SC, Choi SK, Jeong CY. Comparison of perioperative and oncologic outcomes between open and laparoscopic liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4835-4840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wei F, Lu C, Cai L, Yu H, Liang X, Cai X. Can laparoscopic liver resection provide a favorable option for patients with large or multiple intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas? Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3646-3655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhu Y, Song J, Xu X, Tan Y, Yang J. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic liver resection for patients with large or multiple intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas: A propensity score based case-matched analysis from a single institute. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martin SP, Drake J, Wach MM, Ruff S, Diggs LP, Wan JY, Brown ZJ, Ayabe RI, Glazer ES, Dickson PV, Davis JL, Deneve JL, Hernandez JM. Laparoscopic Approach to Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma is Associated with an Exacerbation of Inadequate Nodal Staging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1851-1857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kinoshita M, Kanazawa A, Takemura S, Tanaka S, Kodai S, Shinkawa H, Shimizu S, Murata A, Nishio K, Hamano G, Ito T, Tsukamoto T, Kubo S. Indications for laparoscopic liver resection of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2020;13:46-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ratti F, Rawashdeh A, Cipriani F, Primrose J, Fiorentini G, Abu Hilal M, Aldrighetti L. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as the new field of implementation of laparoscopic liver resection programs. A comparative propensity score-based analysis of open and laparoscopic liver resections. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:1851-1862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kang SH, Choi Y, Lee W, Ahn S, Cho JY, Yoon YS, Han HS. Laparoscopic liver resection versus open liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: 3-year outcomes of a cohort study with propensity score matching. Surg Oncol. 2020;33:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Haber PK, Wabitsch S, Kästner A, Andreou A, Krenzien F, Schöning W, Pratschke J, Schmelzle M. Laparoscopic Liver Resection for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Center Experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2020;30:1354-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wu J, Han J, Zhang Y, Liang L, Zhao J, Han F, Dou C, Liu J, Wu W, Hu Z, Zhang C. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic versus open liver resection with associated lymphadenectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ribero D, Pinna AD, Guglielmi A, Ponti A, Nuzzo G, Giulini SM, Aldrighetti L, Calise F, Gerunda GE, Tomatis M, Amisano M, Berloco P, Torzilli G, Capussotti L; Italian Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Study Group. Surgical Approach for Long-term Survival of Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multi-institutional Analysis of 434 Patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1107-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Krenzien F, Schöning W, Brunnbauer P, Benzing C, Öllinger R, Biebl M, Bahra M, Raschzok N, Cherqui D, Geller D, Han HS, Wakabayashi G, Schmelzle M, Pratschke J; study group of the International Laparoscopic Liver Society (ILLS). The ILLS Laparoscopic Liver Surgery Fellow Skills Curriculum. Ann Surg. 2020;272:786-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kim SH, Han DH, Choi GH, Choi JS, Kim KS. Oncologic Impact of Lymph Node Dissection for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: a Propensity Score-Matched Study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:538-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhou R, Lu D, Li W, Tan W, Zhu S, Chen X, Min J, Shang C, Chen Y. Is lymph node dissection necessary for resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:784-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bagante F, Spolverato G, Weiss M, Alexandrescu S, Marques HP, Aldrighetti L, Maithel SK, Pulitano C, Bauer TW, Shen F, Poultsides GA, Soubrane O, Martel G, Groot Koerkamp B, Guglielmi A, Itaru E, Ruzzenente A, Pawlik TM. Surgical Management of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in Patients with Cirrhosis: Impact of Lymphadenectomy on Peri-Operative Outcomes. World J Surg. 2018;42:2551-2560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, Anthony A, Corrie P, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Wasan H, Ross P, Wall L, Wadsley J, Evans JTR, Stocken D, Praseedom R, Ma YT, Davidson B, Neoptolemos JP, Iveson T, Raftery J, Zhu S, Cunningham D, Garden OJ, Stubbs C, Valle JW, Bridgewater J; BILCAP study group. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:663-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 821] [Article Influence: 136.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhu AX, Pawlik TM, Kooby DA, Schefter TE, Vauthey JN. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer International, 2017. |

| 36. | Cipriani F, Ratti F, Fiorentini G, Reineke R, Aldrighetti L. Systematic review of perioperative and oncologic outcomes of minimally-invasive surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Updates Surg. 2021;73:359-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 37. | Vega EA, De Aretxabala X, Qiao W, Newhook TE, Okuno M, Castillo F, Sanhueza M, Diaz C, Cavada G, Jarufe N, Munoz C, Rencoret G, Vivanco M, Joechle K, Tzeng CD, Vauthey JN, Vinuela E, Conrad C. Comparison of oncological outcomes after open and laparoscopic re-resection of incidental gallbladder cancer. Br J Surg. 2020;107:289-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Belli A, Patrone R, Albino V, Leongito M, Piccirillo M, Granata V, Pasta G, Palaia R, Izzo F. Robotic surgery of gallbladder cancer. Mini-invasive Surg. 2020;4:77. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Regmi P, Hu HJ, Paudyal P, Liu F, Ma WJ, Yin CH, Jin YW, Li FY. Is laparoscopic liver resection safe for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:979-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |