Published online Aug 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i8.918

Peer-review started: January 1, 2020

First decision: April 18, 2020

Revised: July 3, 2020

Accepted: July 19, 2020

Article in press: July 19, 2020

Published online: August 15, 2020

Processing time: 224 Days and 8.2 Hours

The selection of endoscopic treatments for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs) is controversial.

To compare the efficacy and safety of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for SNADETs.

We retrospectively analyzed the data of patients with SNADETs from a database of endoscopic treatment for SNADETs, which included eight hospitals in Fukuoka, Japan, between April 2001 and October 2017. A total of 142 patients with SNADETs treated with EMR or ESD were analyzed. Propensity score matching was performed to adjust for the differences in the patient characteristics between the two groups. We analyzed the treatment outcomes, including the rates of en bloc/complete resection, procedure time, adverse event rate, hospital stay, and local or metastatic recurrence.

Twenty-eight pairs of patients were created. The characteristics of patients between the two groups were similar after matching. The EMR group had a significantly shorter procedure time and hospital stay than those of the ESD group [median procedure time (interquartile range): 6 (3-10.75) min vs 87.5 (68.5-136.5) min, P < 0.001, hospital stay: 8 (6-10.75) d vs 11 (8.25-14.75) d, P = 0.006]. Other outcomes were not significantly different between the two groups (en bloc resection rate: 82.1% vs 92.9%, P = 0.42; complete resection rate: 71.4% vs 89.3%, P = 0.18; and adverse event rate: 3.6% vs 17.9%, P = 0.19, local recurrence rate: 3.6% vs 0%, P = 1; metastatic recurrence rate: 0% in both). Only one patient in the ESD group underwent emergency surgery owing to intraoperative perforation.

EMR has significantly shorter procedure time and hospital stay than ESD, and provides acceptable curability and safety compared to ESD. Accordingly, EMR for SNADETs is associated with lower medical costs.

Core tip: The standard treatment for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs) is controversial. We conducted a multi-center retrospective study, which aimed to compare the treatment outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with those of endoscopic submucosal dissection for SNADETs by propensity score matching analysis. Twenty-eight patients were matched in each group. EMR achieved shorter procedure time and hospital stay than endoscopic submucosal dissection without any significant differences in curability and safety. Therefore, EMR for SNADETs has an advantage in total medical costs of endoscopic treatment.

- Citation: Esaki M, Haraguchi K, Akahoshi K, Tomoeda N, Aso A, Itaba S, Ogino H, Kitagawa Y, Fujii H, Nakamura K, Kubokawa M, Harada N, Minoda Y, Suzuki S, Ihara E, Ogawa Y. Endoscopic mucosal resection vs endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial non-ampullary duodenal tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(8): 918-930

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i8/918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i8.918

Considering the quality of life of patients, endoscopic resection was accepted as an alternative local treatment, instead of invasive surgery for gastrointestinal neoplasms, including those in the stomach, esophagus, colon, and rectum[1-3]. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) - an original endoscopic treatment — is a simple and safe endoscopic resection technique, but it is associated with curability issues, especially for gastric neoplasms[4]. Therefore, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was invented to overcome this problem in patients with gastric neoplasms; ESD resulted in a higher rate of en bloc resection and resulted in precise pathological diagnoses[5]. However, ESD was time-consuming, more difficult to perform, and resulted in a higher rate of adverse events, including perforation and bleeding[6-8].

Endoscopic treatments, instead of pancreaticoduodenectomy, have been subsequently used as local treatments for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs), with a high rate of perioperative complications[9,10]. However, the standard procedure for endoscopic resection remains controversial. In addition, there are limited data regarding the comparison between the two procedures of ESD and EMR[9,11-13]. No randomized-controlled trial till date has compared ESD and EMR owing to various reasons, including patient recruitment, especially the limited number of endoscopic resections performed for SNADETs in each institution. Moreover, confounding bias was noted in previous observational studies, which might have affected the treatment outcomes. Propensity score matching is used to compensate for such biases[14,15]. Accordingly, we conducted a multi-center retrospective study, using propensity score matching to adjust for the differences in the baseline characteristics between patients who underwent EMR and those who underwent ESD. The specific objectives of this study were to compare the treatment outcomes of patients who underwent endoscopic resection and to compare the rates of adverse events in patients who underwent EMR and those who underwent ESD.

The current multi-center, retrospective study was conducted at eight centers, including Kyushu University, Aso Iizuka Hospital, Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital, Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center, Kyushu Rosai Hospital, National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center, National Hospital Organization Fukuokahigashi Medical Center, and Harasanshin Hospital. The study protocol was performed in accordance with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of all eight centers. We reviewed the medical data, including patient characteristics and clinical outcomes, from the EMR/ESD database, endoscopic reports, and medical records at each center. A new database of endoscopic treatment for SNADETs was prepared for this study. Written informed consent for performing endoscopic resection was obtained from each patient before treatment in accordance with the protocol at each institution. However, the need for consent for using the data in this study was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

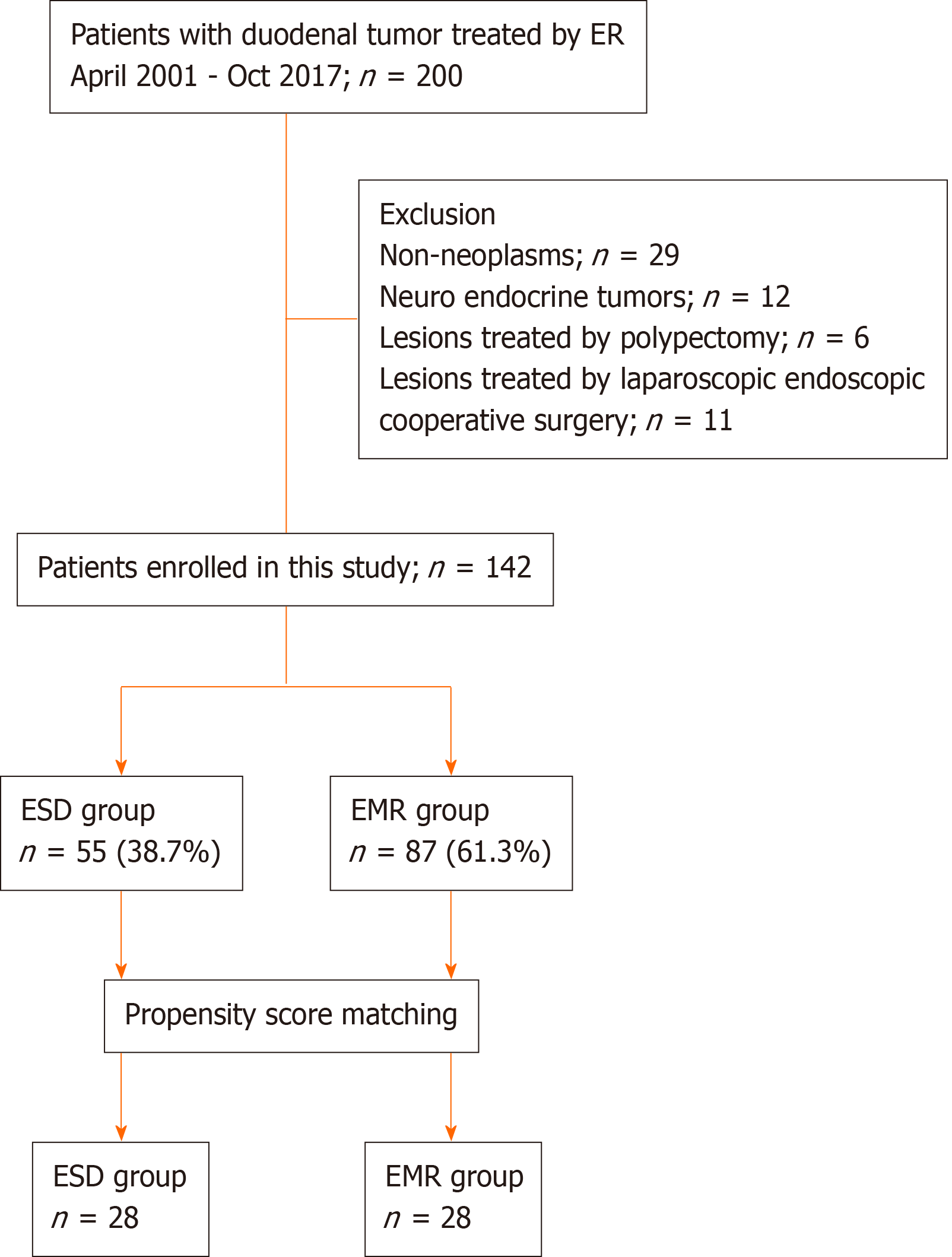

We identified a total of 200 consecutive patients who underwent endoscopic resection for SNADETs in all the centers between April 2001 and October 2017. Subsequently, 58 patients were excluded because of the following reasons: Non-neoplasms in 29 patients, neuro-endocrine tumors in 12 patients, lesions treated with polypectomy in 6 patients, and lesions treated via laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery in 11 patients. The remaining 142 patients with SNADETs were included in the current study. EMR or ESD was performed for each included patient.

The following indications were used for performing endoscopic resection: (1) Histological diagnosis of adenoma or adenocarcinoma on endoscopic biopsy; and (2) Endoscopic suspicion of adenoma or adenocarcinoma without endoscopic biopsy. Endoscopic diagnoses were made via routine endoscopy, magnifying endoscopy, and chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine. If neoplasms were strongly suspected, endoscopic resection was considered as a treatment option without the need for biopsy, because the scar made by biopsy might affect the success of endoscopic resection[16,17].

Endoscopic resection was performed with the patient under intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. A standard single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan or EG-L600WR7; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) was used for endoscopic resection. VIO 300D or ICC200 (ERBE Elektromedizin, GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) was used as an electrical power unit. All patients treated via EMR or ESD were admitted to one of the treating institutions. On day 2 or 3 after endoscopic resection, patients were started on a liquid diet, and patients with an uneventful postoperative course were discharged from the hospital after endoscopic resection. All the endoscopists were experts with an experience of at least 50 EMR and ESD procedures each.

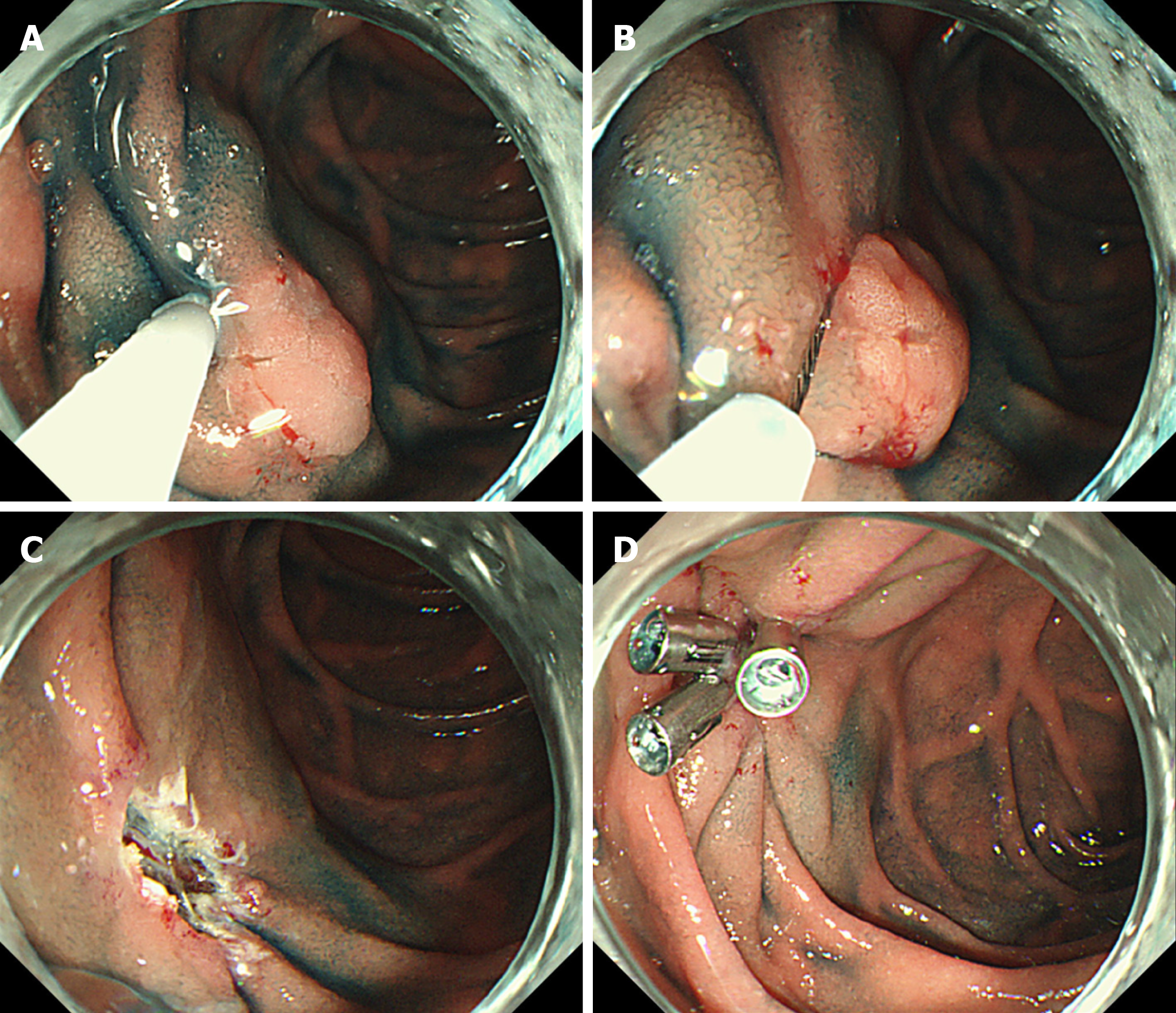

The procedure for EMR has been previously described in detail[9,13]. In brief, the procedure for EMR involves a submucosal injection, followed by mucosal resection using an electrocautery snare (Figure 1A and B). Normal saline or 10% glycerin solution (Glyceol; Taiyo Pharma., Tokyo, Japan) was submucosally injected with a small amount of indigo carmine dye to lift up the lesion[18-20]. Various snares were used according to the tumor size at the endoscopists’ discretion. EMR was performed as described above, with no modifications. If en bloc resection was not achieved during the initial EMR procedure, additional snaring or coagulation was performed using hemostatic forceps or argon plasma coagulation for the residual portion of the lesion. When additional snaring or coagulation was performed after initial EMR, it was considered piecemeal resection.

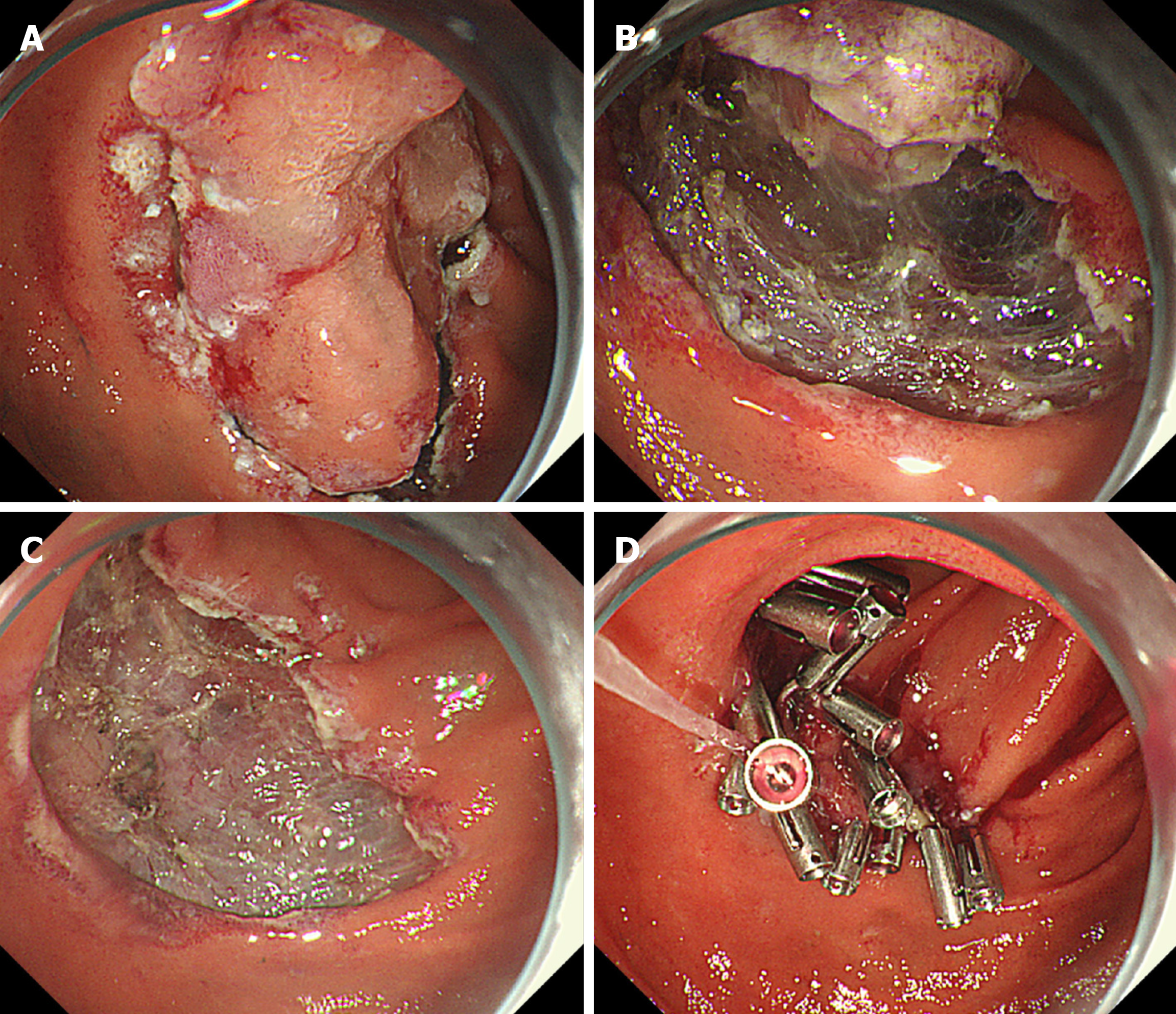

The procedure for ESD has been previously described in detail[9,13,21]. In brief, circumferential marking dots were placed by using the tip of an endo-knife. Sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp 0.4%; Boston Scientific Japan Co., Tokyo, Japan) was submucosally injected with a small amount of indigo carmine dye to achieve adequate and sustained submucosal lifting[18-20]. A circumferential mucosal incision was made around the marking dots, and the submucosal layer was dissected by using the endo-knife (Figure 2A and B). The endoscopic techniques performed, and the type of endo-knives used, including the needle-type knife, insulated tip knife, and scissor-type knife, were at the endoscopists’ discretion. In some cases, dental floss clip traction was used to achieve good visualization and reduce the difficulty in dissection. In other cases, snaring was performed during submucosal dissection. The use of traction and the choice of the snaring method were at the endoscopists’ discretion. Bleeding during the procedure was stopped via coagulation with the endo-knife itself or by using hemostatic forceps. When additional snaring or coagulation was performed after resection of the main lesion via ESD, it was considered piecemeal resection.

Mucosal defects in most cases, including those with intraoperative perforations, were closed after endoscopic resection, including EMR and ESD, via clip closure or tissue shielding methods to prevent delayed bleeding or perforation (Figure 1C and D, Figure 2C and D).

After removal, EMR/ESD specimens were fixed in 10% formalin. The specimens were embedded in 10% paraffin, sectioned at 2-mm intervals, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The pathological diagnoses and evaluation of curability were made by expert gastrointestinal pathologists in each institution. The following valuables were assessed for each tumor: macroscopic type, tumor size, depth of invasion, degree of differentiation, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, and ulceration (scarring).

We analyzed the short-term outcomes of endoscopic resection, such as the rates of en bloc resection and complete resection, procedure time, and incidence of adverse events, including delayed bleeding and intraprocedural or delayed perforation. In addition, we analyzed the local and metastatic recurrences during the follow-up period after endoscopic treatment. The procedure time was defined as the time from the start of mucosal injection to the completion of tumor resection. En bloc resection was defined as resection in a single piece in contrast to piecemeal resection. Complete resection was defined as en bloc resection with horizontal and vertical margins that were free of the tumor. Intraprocedural perforation was identified as a visible break in the duodenal wall confirmed via endoscopy during endoscopic resection. Delayed perforation was diagnosed as the presence of free air confirmed on radiography or computed tomography scans after endoscopic resection without intraprocedural perforation. Delayed bleeding was defined as the clinical evidence of bleeding after endoscopic resection that required endoscopic hemostasis or transfusion. Local recurrence was defined as tumor relapse from the treatment scar, which was diagnosed by endoscopy or biopsy during the follow-up period. Metastatic recurrence was defined as tumor relapse in the lymph nodes and/or other organs, which was diagnosed by computed tomography during the follow-up period.

The sample size could not be calculated because this was a retrospective study. Furthermore, this was not a randomized-controlled study with confounding differences between the two groups. Therefore, propensity score matching was adopted to compensate for the confounding biases that might have influenced the treatment outcomes[22,23]. Logistic regression analysis was performed considering the endoscopic procedures (EMR vs ESD), and the propensity score was analyzed for the following factors: Age (years), sex (man/woman), tumor location (blubs/second or third portion), tumor morphology (protruded/others), tumor size (mm, ≥ 11 mm/ < 11 mm), tumor depth (mucosa/submucosa), and histology (adenoma/ adenocarcinoma). This model yielded an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 0.86, which indicated a good predictive power. The propensity score for ESD was calculated using logistic regression analysis, which indicated the possibility that a patient would undergo ESD. After estimating the propensity scores, patients in the ESD group were matched to patients in the EMR group. The matching algorithm used calipers with a width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the log of the propensity score without replacement. The effect of the matching was evaluated in terms of the absolute standardized difference.

Categorical variables were presented as the number and percentage. Continuous variables that were distributed abnormally were presented as the median and interquartile range. The differences in the baseline clinicopathological characteristics and treatment outcomes of this study were compared between the two groups by using Fisher’s exact test for categorical data or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data that were not distributed normally. P values < 0.05 were statistically significant for all tests. All statistical data analyses were performed using JMP software (version 14.0.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

EMR was performed in 87 patients and ESD in 55. Figure 3 shows the flowchart of patient enrollment. The baseline clinicopathological characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown Table 1. The EMR group included significantly fewer women than the ESD group. In addition, the median tumor size was significantly smaller in the EMR group than in the ESD group [7.0 (interquartile range: 5-10) mm vs 15 (10.5-20) mm, P < 0.001]. The rate of tumors > 11 mm was significantly lower in the EMR group than in the ESD group (18.4% vs 74.5%, P < 0.001). The rate of adenocarcinoma was significantly lower in the EMR group than in the ESD group (17.2% vs 43.6%, P = 0.001). There were no significant differences in the other factors between the two groups.

| All, n = 142 | EMR group, n = 87 | ESD group, n = 55 | P value | |

| Age, yr | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 63.5 (57-71.75) | 62 (57-70) | 66 (59-73.5) | 0.15 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 79 (55.6) | 56 (64.4) | 23 (41.8) | 0.01 |

| Female | 63 (44.4) | 31 (35.6) | 32 (58.2) | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | ||||

| Bulbs | 32 (22.5) | 17 (19.5) | 15 (27.3) | 0.31 |

| Second portion or later | 110 (77.5) | 70 (80.5) | 40 (72.7) | |

| Morphology, n (%) | ||||

| Flat or depressed | 28 (19.7) | 17 (19.5) | 11 (20.0) | 1 |

| Protruded | 114 (80.3) | 70 (80.5) | 44 (80.0) | |

| Tumor size, mm | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (5.25-15) | 7 (5-10) | 15 (10.5-20) | < 0.001 |

| < 11 mm | 85 (59.9) | 71 (81.6) | 14 (25.5) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 11 mm | 57 (40.1) | 16 (18.4) | 41 (74.5) | |

| Tumor depth, n (%) | ||||

| Mucosa | 139 (97.9) | 86 (98.9) | 53 (96.4) | 0.56 |

| Submucosa | 3 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Histology, n (%) | ||||

| Adenoma | 103 (72.5) | 72 (82.8) | 31 (56.4) | 0.001 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 39 (27.5) | 15 (17.2) | 24 (43.6) | |

The treatment outcomes before propensity score matching are shown in Supplemental Table 1. In the EMR group, the median procedure time was 5 (3.5-10) min and the rates of en bloc and complete resection were 87.4% and 71.3%, respectively. The rate of adverse events in the EMR group was 4.6% (observed in 4 of 87 patients); delayed bleeding occurred in 4.6% of the patients (4/87), and neither intraoperative nor delayed perforation was observed in any patient. The median hospital stay in the EMR group was 7.0 (6-9) d. In contrast, in the ESD group, the median procedure time was 90 (67-134.5) min and the rates of en bloc and complete resection were 94.5% and 83.6%, respectively. The rate of adverse events in the ESD group was 18.2% (observed in 10 of 55 patients); delayed bleeding occurred in 1.8% of the patients (1/55), intraoperative perforation in 12.7% (7/55), and delayed perforation in 3.6% (2/55). The median hospital stay in the ESD group was 11 (9-14) d. In fact, only one patient with intraoperative perforation in the ESD group required emergency surgery immediately after ESD. Nevertheless, none of the patients in either group died due to adverse events.

Follow-up duration and 1-year follow-up rate were not significantly different between the two groups: Median follow-up duration, 24.5 (15-53.75) mo; 1-year follow-up rate, 81.0% (115/142). Three cases of local recurrence occurred in EMR, which were successfully managed by salvage endoscopic treatment. No metastatic recurrence occurred in either groups.

Twenty-eight patients in the EMR group were matched with 28 patients in the ESD group by using propensity score matching. The matching factors between both the groups, which are shown in Table 2, were quite similar without any significant differences. All the absolute standardized differences ranged within 1.96(2/n)1/2, which indicated well-balanced characteristics[22]. The median tumor size was 11 (6.25-15) mm in the EMR group and 10.5 (8-13) mm in the ESD group (P = 0.90).

| EMR group, n = 28 | ESD group, n = 28 | P value | ASD | |

| Variable matching between groups | ||||

| Age, yr; ≥ 65/< 65 | 8/20 | 6/22 | 0.76 | 0.17 |

| Sex; male/female | 17/11 | 16/12 | 1 | 0.073 |

| Tumor location; bulbs/others | 8/20 | 6/22 | 0.67 | 0.17 |

| Morphology; protruded/flat or depressed | 22/6 | 23/5 | 1 | 0.090 |

| Histology; adenocarcinoma/adenoma | 8/20 | 7/21 | 1 | 0.081 |

| Tumor depth; mucosa/submucosa | 27/1 | 27/1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tumor size; median (IQR) | 11 (6.25-15) | 10.5 (8-13) | 0.90 | 0.026 |

| Tumor size; ≥ 11 mm/< 11 mm | 14/14 | 14/14 | 1 | 0 |

The treatment outcomes of patients in the EMR and ESD groups after propensity score matching are summarized in Table 3. The procedure time was significantly shorter in the EMR group than in the ESD group [6 (3-10.75) min vs 87.5 (68.5-136.5) min, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the median hospital stay was significantly shorter in the EMR group than in the ESD group [8 (6-10.75) d vs 11 (8.25-14.75) d, P = 0.006]. There were no significant differences in en bloc resection and curative resection rates between both groups (en bloc resection rate: 82.1% vs 92.9%, P = 0.42; complete resection rate: 71.4% vs 89.3%, P = 0.18). There was also no significant difference in the rate of adverse events between both groups (3.6% vs 17.9%, P = 0.19). Delayed bleeding in the EMR group was successfully managed using a conservative approach without surgery. Only one patient with intraoperative perforation in the ESD group required emergency surgery immediately after ESD. None of the patients in either group died due to adverse events. As for recurrence events, only one local recurrence was observed in the EMR group, and no metastatic recurrence was seen during the follow-up period.

| EMR group, n = 28 | ESD group, n = 28 | P value | |

| Procedure time, min | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3-10.75) | 87.5 (68.5-136.5) | < 0.001 |

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 23 (82.1) | 26 (92.9) | 0.42 |

| Complete resection, n (%) | 20 (71.4) | 25 (89.3) | 0.18 |

| Closure of mucosal defects, n (%) | 24 (85.7) | 27 (96.4) | 0.35 |

| Adverse events, n (%) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (17.9) | 0.19 |

| Intraoperative perforation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (10.7) | 0.24 |

| Delayed perforation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 |

| Delayed bleeding, n (%) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Emergency surgery, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 |

| Hospital stay, d | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (6-10.75) | 11 (8.25-14.75) | 0.006 |

| Follow-up duration, mo | 23 (11-35.5) | 24 (9.75-57.5) | 0.831 |

| Median (IQR) | |||

| One-year follow-up, n (%) | 21 (75) | 20 (71.4) | 1 |

| Local recurrence, n (%) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Metastatic recurrence, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to compare the efficacy and safety of EMR with those of ESD for SNADETs using propensity score matching. Although ESD tended to result in a higher complete resection rate than did EMR, ESD was a significantly longer procedure and required longer hospital stay with a tendency of having a higher adverse event rate. In fact, one patient in the ESD group required emergency surgery for a perforation. Local recurrent lesions in EMR were successfully treated by endoscopic resection. Therefore, although ESD was more effective than EMR, all SNADETs cannot be treated with ESD because of the possible risk of adverse events and higher cost of hospitalization.

ESD for duodenal tumors achieved higher curability rates with a higher adverse event risk than EMR[11-13]. However, these previous studies, as well as the current study, were retrospective studies and not randomized-controlled trials. Therefore, there were some biases owing to the difference in the background characteristics of each group. Some factors are associated with the outcomes of endoscopic resection for SNADETs. For example, the tumor size was associated with the rate of adverse events after endoscopic resection and the en bloc resection rate[24,25]. In addition, the presence of a tumor in the distal part of the second portion, especially distal to the ampulla of Vater, was associated with the occurrence of delayed perforation after endoscopic resection[26,27]. Therefore, we performed propensity score matching in the current study instead of a randomized-controlled trial. All such factors that were associated with the treatment outcomes were included as covariates; this contributed to the reduction of bias. Accordingly, the factors were quite similar between both groups after propensity score matching. Therefore, the current clinical study had fewer biases than previous studies.

Previous reports suggested that duodenal tumors < 20 mm in size should be treated with EMR and not ESD[11]. However, approximately 60% of duodenal tumors with a diameter of 11-20 mm were treated with ESD in a recent large-scale case series[28]. Accordingly, the criteria for selecting the treatment method for SNADETs < 20 mm are still controversial, and more studies are required to compare the treatment outcomes between EMR and ESD. In the current study, most lesions were < 20 mm, with more than half of the included lesions being 11-20 mm in size. Therefore, we believe that the results of the current study can be used to standardize the treatment method for SNADETs, especially for small lesions.

ESD resulted in an extremely high curability rate in the current study; the en bloc resection rate was > 90%, and the complete resection rate also reached approximately 90%. These outcomes are similar to or better than those of previous studies[28-31]. In addition, although the curability of EMR in the current study seemed to be lower than that of ESD, the difference was not significant. In previous studies, piecemeal resection was required during EMR for lesions that were > 10-15 mm in diameter. In fact, the en bloc resection rate exceeded 80%, and the complete resection rate was approximately 70% in the current study, both of which are higher than those reported in previous studies[32]. The advancements in the endoscopic devices and the electrosurgical power unit, as well as advancements in the skill of the endoscopists, might have contributed to the better treatment outcomes. During follow-up, three local recurrences before matching (one local recurrence after matching) were observed only in the EMR group, although no recurrence was observed in the ESD group. All recurrent lesions were attributed to the piecemeal resection but could be managed by salvage endoscopic treatment. Furthermore, no metastatic lesion was observed in either group during the follow-up period. The high rate of en bloc resection in the EMR group might contribute to the comparably low rate of local recurrence as that in ESD group. Accordingly, the curative potential of EMR in the current study seems to be acceptable, even though the follow-up duration was short.

Duodenal ESD is difficult to perform because the duodenum has a very thin wall ( < 2 mm thickness) with limited space surrounding the duodenum, and therefore, the maneuverability around the space is limited, possibly resulting in a higher risk of perforation than ESD for lesions in the rest of the gastrointestinal tract[10,33]. Considering the safety of ESD and EMR in the current study, the adverse event rates after EMR and ESD were not significantly different. After matching, adverse events occurred in only 1 patient who underwent EMR, whereas adverse events were observed in 5 patients who underwent ESD, which were quite low compared with those obtained in previous studies[29-31]. Especially, no delayed bleeding occurred in ESD after matching. This result might be owing to the closure of the mucosal defect after ESD. In fact, in the current study, closure of the perforation site and prophylactic endoscopic closure of the mucosal defect were performed. In a previous study, prophylactic endoscopic closure contributed to the prevention of delayed bleeding[34]. Furthermore, complete closure of the mucosal defects after duodenal ESD reduced the risk of delayed adverse events[35]. The mucosal defect was closed in almost all patients who underwent ESD (96.4%, 27/28), which might have contributed to the low rate of delayed adverse events. However, 1 patient who underwent ESD could not be managed conservatively, and, therefore, required emergency surgery.

The time taken for the procedure and the hospital stay were significantly shorter in patients who underwent EMR than in those who underwent ESD. The results of the current study showed that a shorter procedure time for EMR than for ESD reduces the cost of medical staff, including the operator for the endoscopic procedure, assistant for manipulating the device, and assistant for monitoring patients. In addition, the endo-knife used during ESD with hemostatic forceps is much more expensive than the snare used during EMR. Moreover, the low rate of adverse events might result in shorter hospitalization, thereby contributing to the cost of hospital stay. A previous study also showed that patients who underwent ESD had lower medical costs than those who underwent surgery, although the data were of patients with early gastric cancer[36]. Thus, EMR will contribute to a reduction in the total medical cost of endoscopic resection, compared with ESD.

The current study had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study and did not include a randomized population. Although propensity score matching reduced the confounding biases, not all biases, such as the endoscopists’ preference of EMR or ESD, could be eliminated. There was a possibility of selection bias because lesions that could be easily snared were selected for EMR. Second, lesions treated with EMR tended to include adenomas, mucosal lesions, and small lesions. These rates among two groups were similar after matching, but the comparison of treatment outcomes was limited primarily to such lesions. Therefore, it is questionable whether these findings could be generalized to adenocarcinomas, submucosal invasive lesions, or large lesions. Third, the sample size was relatively small owing to propensity score matching, even though this was a multi-center study. Therefore, the differences in the effectiveness and safety between EMR and ESD are unclear for SNADETs. A prospective study with a larger randomized population is expected to be conducted in the future. Fourth, the follow-up period in this study was insufficient to evaluate long-term outcomes. Median follow-up duration was 24.5 (15-53.75) mo, and the 1-year follow up rate was 81.0% (115/142). Longer follow-up will be required to evaluate the accurate curative potential of endoscopic resection. Fifth, new advanced treatment methods, including underwater EMR, cold polypectomy, and laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery, have been used as local treatments for SNADETs, in addition to conventional EMR or ESD[37-39]. Such methods were not performed for treating SNADETs in the current study period or patients who underwent these procedures were excluded from this study. Accordingly, the treatment outcomes should be compared between conventional EMR and ESD and such new procedures in future studies.

In conclusion, the results of our study demonstrated that EMR required a significantly shorter procedure time and hospital stay than did ESD, with comparable curative potential and a lower risk of adverse events. Therefore, EMR should preferably be selected as a local treatment for SNADETs, especially for adenomas, mucosal lesions, and small lesions.

Endoscopic treatments have been used as local treatments for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs) instead of surgery.

It remains to be determined whether endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is more appropriate for treating SNADETs.

The aim of this multi-center retrospective study was to compare the treatment outcomes of EMR and ESD for SNADETs.

Patients with SNADETs treated by EMR or ESD at eight institutions between April 2001 and October 2017. Patients were categorized into an EMR group or an ESD group. Propensity score matching analysis was conducted to compensate for confounding differences between the two groups that may affect the outcomes. After matching, the treatment outcomes were compared between the two groups.

A total of 152 patients were included and 28 pairs were matched. The EMR group had significantly shorter procedure time and hospital stay than the ESD group. The rates of en bloc resection, complete resection, and adverse events were not significantly different between the two groups.

EMR provides acceptable efficacy and safety with a significantly shorter procedure time and hospital stay than ESD. Additionally, EMR for SNADETs has an advantage in total medical costs of endoscopic treatment.

This was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size and follow-up duration. Therefore, further large-scale, randomized, prospective studies are needed.

We thank all members at the Department of Medicine and Bioregulatory Science, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University for cooperating with us in the data collection.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chow WK, Dinç T, Figueiredo PN, Hu B S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kitagawa Y, Uno T, Oyama T, Kato K, Kato H, Kawakubo H, Kawamura O, Kusano M, Kuwano H, Takeuchi H, Toh Y, Doki Y, Naomoto Y, Nemoto K, Booka E, Matsubara H, Miyazaki T, Muto M, Yanagisawa A, Yoshida M. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan Esophageal Society: part 1. Esophagus. 2019;16:1-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M, Kudo SE, Tsuruta O, Sugihara KI, Watanabe T, Saitoh Y, Igarashi M, Toyonaga T, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T, Sugita A, Sugano K, Fujimoto K, Tajiri H. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakamoto S, Sakai Y, Kasanuki J, Kondo F, Ooka Y, Kato K, Arai M, Suzuki T, Matsumura T, Bekku D, Ito K, Tanaka T, Yokosuka O. Indications for the use of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer in Japan: a comparative study with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2009;41:746-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Shimura T, Sasaki M, Kataoka H, Tanida S, Oshima T, Ogasawara N, Wada T, Kubota E, Yamada T, Mori Y, Fujita F, Nakao H, Ohara H, Inukai M, Kasugai K, Joh T. Advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection over conventional endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:821-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto S, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Kajimoto N, Ogiyama H, Fukushima Y, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Iishi H, Tatsuta M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer performed by supervised residents: assessment of feasibility and learning curve. Endoscopy. 2009;41:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao Y, Wang C. Long-Term Clinical Efficacy and Perioperative Safety of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection versus Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Early Gastric Cancer: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3152346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nonaka S, Oda I, Tada K, Mori G, Sato Y, Abe S, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga S, Nakajima T, Matsuda T, Taniguchi H, Saito Y, Maetani I. Clinical outcome of endoscopic resection for nonampullary duodenal tumors. Endoscopy. 2015;47:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Esaki M, Suzuki S, Ikehara H, Kusano C, Gotoda T. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of superficial non-ampullary duodenal tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;10:156-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Matsumoto S, Yoshida Y. Selection of appropriate endoscopic therapies for duodenal tumors: an open-label study, single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8624-8630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hoteya S, Furuhata T, Takahito T, Fukuma Y, Suzuki Y, Kikuchi D, Mitani T, Matsui A, Yamashita S, Nomura K, Kuribayashi Y, Iizuka T, Kaise M. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection and Endoscopic Mucosal Resection for Non-Ampullary Superficial Duodenal Tumor. Digestion. 2017;95:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Quénéhervé L, Margos W, Shaza L, Ivekovic H, Moreels TG, Yeung R, Piessevaux H, Coron E, Jouret-Mourin A, Deprez PH. Comparative analysis of ESD versus EMR in a large European series of non-ampullary superficial duodenal tumors. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1008-E1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Esaki M, Suzuki S, Hayashi Y, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Hosokawa T, Tsuruta S, Minoda Y, Hata Y, Ogino H, Akiho H, Ihara E, Ogawa Y. Propensity score-matching analysis to compare clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in the postoperative and non-operative stomachs. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Esaki M, Suzuki S, Hayashi Y, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Hosokawa T, Ogino H, Akiho H, Ihara E, Ogawa Y. Splash M-knife versus Flush Knife BT in the technical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yamasaki Y, Takeuchi Y, Kanesaka T, Kanzaki H, Kato M, Ohmori M, Tonai Y, Hamada K, Matsuura N, Iwatsubo T, Akasaka T, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Okada H, Iishi H. Differentiation between duodenal neoplasms and non-neoplasms using magnifying narrow-band imaging - Do we still need biopsies for duodenal lesions? Dig Endosc. 2020;32:84-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kinoshita S, Nishizawa T, Ochiai Y, Uraoka T, Akimoto T, Fujimoto A, Maehata T, Goto O, Kanai T, Yahagi N. Accuracy of biopsy for the preoperative diagnosis of superficial nonampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:329-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ono S, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A, Shimizu Y, Oka M, Ogura K, Kawabe T, Ichinose M, Omata M. Successful outcomes of a novel endoscopic treatment for GI tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with a mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, glycerin, and sugar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kashimura K, Mizushima Y, Oka M, Enomoto S, Kakushima N, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Iguchi M, Shimizu Y, Ichinose M, Omata M. Comparison of various submucosal injection solutions for maintaining mucosal elevation during endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2004;36:579-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kashimura K, Mizushima Y, Oka M, Matsuura T, Enomoto S, Kakushima N, Imagawa A, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Iguchi M, Shimizu Y, Ichinose M, Omata M. Different mixtures of sodium hyaluronate and their ability to create submucosal fluid cushions for endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2004;36:584-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Minoda Y, Akahoshi K, Otsuka Y, Kubokawa M, Motomura Y, Oya M, Nakamura K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early duodenal tumor using the Clutch Cutter: a preliminary clinical study. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E267-E268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083-3107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3915] [Cited by in RCA: 4419] [Article Influence: 276.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | D'Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265-2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Basford PJ, George R, Nixon E, Chaudhuri T, Mead R, Bhandari P. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: comparison of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques and the risks of late delayed bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1594-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Valli PV, Mertens JC, Sonnenberg A, Bauerfeind P. Nonampullary Duodenal Adenomas Rarely Recur after Complete Endoscopic Resection: A Swiss Experience Including a Literature Review. Digestion. 2017;96:149-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zou J, Chai N, Linghu E, Zhai Y, Li Z, Du C, Li L. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic resection for non-ampullary duodenal laterally spreading tumors. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:4048-4056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Inoue T, Uedo N, Yamashina T, Yamamoto S, Hanaoka N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Takahashi H, Eguchi H, Ohigashi H. Delayed perforation: a hazardous complication of endoscopic resection for non-ampullary duodenal neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yahagi N, Kato M, Ochiai Y, Maehata T, Sasaki M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Nakayama A, Fujimoto A, Goto O, Uraoka T. Outcomes of endoscopic resection for superficial duodenal epithelial neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Honda T, Yamamoto H, Osawa H, Yoshizawa M, Nakano H, Sunada K, Hanatsuka K, Sugano K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial duodenal neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Matsumoto S, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for duodenal tumors: a single-center experience. Endoscopy. 2013;45:136-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jung JH, Choi KD, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Jung HY, Choi KS, Lee GH, Song HJ, Kim DH, Kim MY, Bae SE, Kim JH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for sessile, nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Endoscopy. 2013;45:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Lourdusamy V, Zhu X, Hawes RH, Varadarajulu S. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic mucosal resection of non-ampullary duodenal polyps: a systematic review. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E699-E708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ochiai Y, Kato M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Nakayama A, Sasaki M, Fujimoto A, Maehata T, Goto O, Yahagi N. Current Status and Challenges of Endoscopic Treatments for Duodenal Tumors. Digestion. 2019;99:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hoteya S, Kaise M, Iizuka T, Ogawa O, Mitani T, Matsui A, Kikuchi D, Furuhata T, Yamashita S, Yamada A, Kimura R, Nomura K, Kuribayashi Y, Miyata Y, Yahagi N. Delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for non-ampullary superficial duodenal neoplasias might be prevented by prophylactic endoscopic closure: analysis of risk factors. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kato M, Ochiai Y, Fukuhara S, Maehata T, Sasaki M, Kiguchi Y, Akimoto T, Fujimoto A, Nakayama A, Kanai T, Yahagi N. Clinical impact of closure of the mucosal defect after duodenal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim B, Kim BJ, Seo IK, Kim JG. Cost-effectiveness and short-term clinical outcomes of argon plasma coagulation compared with endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of gastric low-grade dysplasia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yamasaki Y, Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Hanaoka N, Akasaka T, Kato M, Hamada K, Tonai Y, Matsuura N, Kanesaka T, Arao M, Suzuki S, Iwatsubo T, Shichijo S, Nakahira H, Ishihara R, Iishi H. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial nonampullary duodenal adenomas. Endoscopy. 2018;50:154-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Maruoka D, Matsumura T, Kasamatsu S, Ishigami H, Taida T, Okimoto K, Nakagawa T, Katsuno T, Arai M. Cold polypectomy for duodenal adenomas: a prospective clinical trial. Endoscopy. 2017;49:776-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Irino T, Nunobe S, Hiki N, Yamamoto Y, Hirasawa T, Ohashi M, Fujisaki J, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery for duodenal tumors: a unique procedure that helps ensure the safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2015;47:349-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |