Published online May 15, 2020. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i5.549

Peer-review started: February 3, 2020

First decision: February 25, 2020

Revised: April 14, 2020

Accepted: April 24, 2020

Article in press: April 24, 2020

Published online: May 15, 2020

Processing time: 100 Days and 13.6 Hours

The implications of neutropenia after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) treatment have never been investigated.

To evaluate the occurrence of neutropenia and its effect on the risk of increased Clavien-Dindo morbidity as well as its effect on overall or disease-free survival.

All patients with colorectal peritoneal metastases (1996-2015) completing cytoreductive surgery and oxaliplatin-based HIPEC treatment from a bi-institutional database (Uppsala and Sydney) were included in the study. Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4 morbidity differences between the neutropenia group vs non-neutropenia group were calculated and Kaplan-Meier curves with log rank test were rendered. Univariate and multivariable Cox regression models for disease-free survival were implemented.

Two hundred and forty-six patients were identified – 32 postoperative any-grade neutropenia patients and 214 non-neutropenia patients. The neutropenia group had more combination oxaliplatin + irinotecan treatment than the non-neutropenia group (66% vs 13%, P = 0.0001). The neutropenia group was not associated with increased Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4 morbidity. Median overall survival was 53 mo vs 37 mo for the neutropenia and non-neutropenia group, P = 0.07. Median disease-free survival was 16 mo vs 11 mo, respectively, P = 0.02. Neutropenia was an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival with hazard ratio: 0.58, 95% confidence interval: 0.36-0.95, P = 0.03.

13% of patients developed neutropenia which was not associated with increased Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4 morbidity. Neutropenia was an independent positive prognostic factor for disease-free survival and was associated with more intense HIPEC treatment. This is in direct contrast to the current paradigm of decreasing the treatment intensity.

Core tip: We investigated neutropenia after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) treatment of colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastases. The frequency of neutropenia was 13%; however, it was much more common in the oxaliplatin + irinotecan HIPEC treatment than in the single oxaliplatin HIPEC treatment. Neutropenia did not increase the risk of Clavien-Dindo morbidity. Furthermore, it was found to be an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival. In conclusion, we found that neutropenia doesn’t appear to be a toxicity limiting factor as it does not increase the postoperative morbidity, but rather a positive prognostic factor that may predict a better outcome.

- Citation: Cashin PH, Ghanipour L, Enblad M, Morris DL. Neutropenia in colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin-based hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: An observational cohort study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; 12(5): 549-558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v12/i5/549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v12.i5.549

Colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastases (CRCPM) is a loco-regional disease that now has a standard treatment-cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC)[1-4]. The road to this conclusion has been long and tedious. However, this is a significant paradigm shift as CRCPM has long been considered a palliative situation; but now, it is considered a metastatic disease amenable to treatment with curative intent. The cure rate is somewhere between 15% and 25% depending on selection criteria[3,5]. Moreover, the median survival is now approximately 40 mo for CRS and HIPEC treatment of CRCPM[6].

CRS and HIPEC have always been a package deal for the treatment of CRCPM. Only recently, has a trial evaluating the isolated effect of HIPEC been conducted–the Prodigy 7 trial[6]. This trial has been discussed extensively in the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International Conferences and also in recent published editorial comments[7]; all the while, the study itself has yet to be published in its final form. The French consortium should be applauded for the effort that the trial has taken. However, as pointed out by Ceelen[7], the trial has unfortunately a few flaws of which the important one is the sample size calculation. Despite these criticisms, a number of centers have been opting to switch HIPEC regimens from oxaliplatin-based to mitomycin C, something alluded to in a recent review of mitomycin C and cisplatin HIPEC for treatment of CRCPM[8].

There appears to be some uncertainty as how to interpret the Prodigy 7 trial. The Nordic Peritoneal Oncology Group has been discussing a follow-up trial but have had difficulties finding an appropriate way forward. One suggestion that has developed is to evaluate HIPEC by intensifying the HIPEC treatment instead of having a non-HIPEC arm. However, one previous study comparing oxaliplatin HIPEC with intensified combination oxaliplatin and irinotecan HIPEC concluded that the combination was highly morbid[9]. However, this study found one main factor accounting for the significant morbidity increase and that was neutropenia[9]. Neutropenia is a sign of systemic toxicity and as HIPEC is meant to be a locoregional treatment; systemic toxicity has previously signified a negative unwanted effect.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of neutropenia and investigate its effect on other morbidity, disease-free, and overall survival. The hypothesis was that neutropenia would have a detrimental effect on both morbidity and survival, thus lending support for the current treatment paradigm of low-dose single drug HIPEC.

The cohort for this study was taken from a bi-institutional database from Sydney Australia (St. Georges Hospital) and Uppsala University Hospital. Both centers have had prospectively collected databases on all HIPEC procedures from 1996 in Sydney and from 2003 in Uppsala. All colorectal cancer patients from both institution’s HIPEC database being treated from 1996 (Sydney) or 2003 (Uppsala) to the end of 2015 were selected for inclusion. As only 10 patients with mitomycin C from both institutions developed neutropenia, the study was confined to the oxaliplatin-based treatment group.

The oxaliplatin cohort was divided into two groups – one postoperative any-grade neutropenic group and one group without postoperative neutropenia. Neutropenia was defined as neutrophil counts under 1.5 × 109/L. Demographics and treatment-related variables were compared between the groups. The main endpoints were difference in Clavien-Dindo morbidity, reoperation rate, postoperative mortality, overall and disease-free survival. Permission was acquired from the Uppsala county ethical board for data collection related to the study from Swedish patients. Corresponding ethical review board approval was acquired for patients from Sydney, Australia. Funding for the trial was provided by ALF funds from the Uppsala University Hospital (No grant number).

All patients were operated according to standard peritonectomy techniques with resection of abdominal hollow and solid organs according to cytoreductive surgery standards. The peritoneal cancer index score was determined at the beginning of each surgery prior to continuing surgical resections. The oxaliplatin HIPEC was administered as a planned dose of 350-460 mg/m2 in 1.5 L/m2 glucose solution at 42o hyperthermia. Any dosage under 350 was considered reduced dose. The oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC was administered in the same perfusion carrier at the same temperature with a planned dose of 360 mg/m2 oxaliplatin and 360 mg/m2 irinotecan. All doses under 300 mg/m2 for either drug was considered dose reduction. Both treatments lasted for 30 min.

Statistics were calculated using Statisica 13.4.0.14, TIBCO Software Inc. Descriptive statistics were used as necessary. Fisher exact test was used for 2 × 2 categorical testing and Pearson X2 testing was used for multiple categories. Student t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables such as peritoneal cancer index and age while Mann-Whitney-U test was used for non-parametric variables such as carcinoembryonic antigen. Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional regression analysis was used to evaluate potential prognostic variables and all significant univariate variables were applied in a multivariable setting to evaluate their independent prognostic value. A two variable Cox proportional regression analysis was performed with time period of treatment and neutropenia to evaluate if the time period affected the prognostic effect of neutropenia. The time period was divided into 2 periods using the median date of the cohort as cut-off between periods. Missing data was not imputed. It occurred most often in categorical variables and was kept as a separate group. Concerning endpoints, no missing data existed for morbidity or overall survival. One missing data in disease-free survival and this patient was excluded from analysis. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to display the overall survival and disease-free survival of the two groups. The log-rank test was used to test survival differences. P values below 0.05 were considered significant.

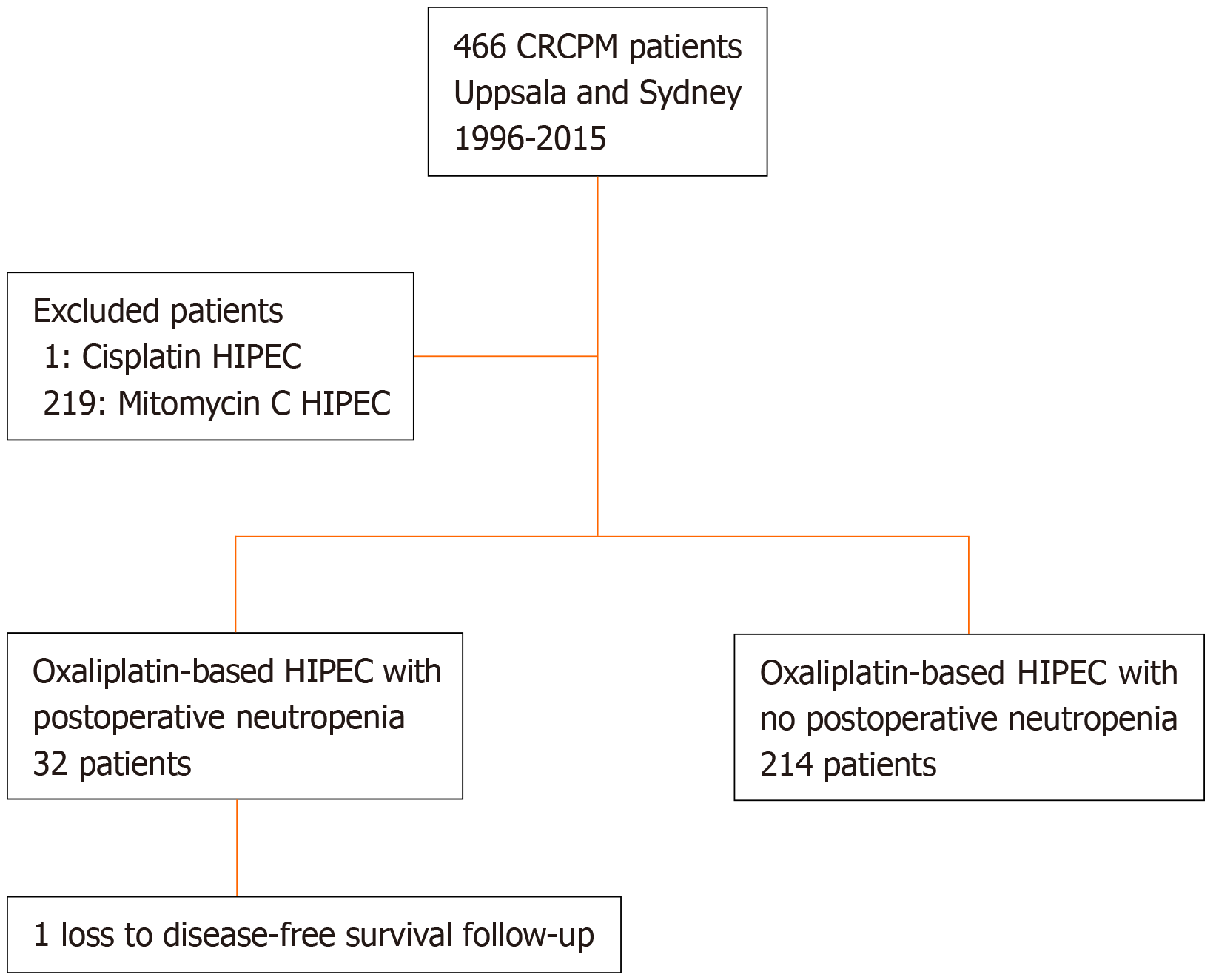

The database selection is displayed in the flow chart (Figure 1). In Table 1, demographics and treatment related variables are reported. The peritoneal cancer index and operating time were significantly more increased in the neutropenia group indicating that the disease was generally more extensive in this group. Furthermore, the neutropenia group had more synchronous cases of CRCPM, more node-positive disease, and was older. Moreover, the neutropenia group also received more neoadjuvant therapy. Omitting missing data on grading (n = 2), 20% of patients had severe neutropenia (< 0.5 × 109/L), 13% had moderate neutropenia (< 1.0 and > 0.5 × 109/L), and 67% had mild neutropenia (> 1.0 × 109/L). The median follow-up time was 11 years.

| Neutropenia, n = 32 | No neutropenia, n = 214 | P value | Whole cohort, n = 246 | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 60 ± 11 | 55 ± 13 | 0.048 | 55 ± 14 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.12 | |||

| Male | 18 (56) | 93 (43) | 111 (45) | |

| Female | 14 (44) | 121 (57) | 135 (55) | |

| Primary tumour, n (%) | 0.79 | |||

| Colon | 30 (94) | 189 (88) | 219 (89) | |

| Rectum | 2 (6) | 24 (11) | 26 (11) | |

| Colorectal unspecified | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (< 1) | |

| PM disease, n (%) | 0.021 | |||

| Synchronous | 23 (72) | 107 (50) | 115 (52) | |

| Metachronous | 9 (28) | 107 (50) | 106 (48) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | |

| Neoadjuvant for PM disease, n (%) | 23 (72) | 100 (47) | 0.035 | 123 (50) |

| Node positive primary, n (%) | 19 (59) | 154 (72) | 0.048 | 173 (70) |

| Missing data | 4 (12) | 5 (2) | 9 (4) | |

| Differentiation, n (%) | 0.4 | |||

| Poor | 10 (31) | 56 (26) | 66 (27) | |

| Moderat/high | 20 (62) | 149 (70) | 169 (79) | |

| Missing data | 2 (9) | 9 (4) | 11 (4) | |

| PCI, mean ± SD | 15.4 ± 10 | 12.1 ± 8 | 0.043 | 12.5 ± 9 |

| Liver metastases, n (%) | 4 (12) | 32 (15) | 0.7 | 36 (15) |

| CC score, n (%) | 0.31 | |||

| 0 | 28 (88) | 194 (91) | 222 (90) | |

| 1 | 2 (6) | 15 (7) | 17 (7) | |

| 2 | 2 (6) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1%) | |

| HIPEC, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Oxaliplatin | 11 (34) | 187 (87) | 198 (80) | |

| Oxali + irinotecan | 21 (66) | 27 (13) | 48 (20) | |

| HIPEC dose reduction, n (%) | 9 (28) | 26 (12) | 0.07 | 35 (14) |

| Missing data | 14 (44) | 53 (25) | 67 (27) | |

| EPIC administration, n (%) | 6 (19) | 18 (8) | 0.0001 | 24 (10) |

| Operating time, mean ± SD | 552 ± 129 | 461 ± 123 | 0.55 | 473 ± 127 |

| Return to OR postop, n (%) | 2 (6) | 24 (11) | 0.1 | 26 (11) |

| Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4, n (%) | 6 (19) | 67 (31) | 0.18 | 73 (30) |

| Postop in-hospital mortality | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 0.13 | |||

| Yes | 14 (44) | 113 (53) | 127 (52) | |

| No | 18 (56) | 92 (43) | 110 (45) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 9 (4) | 9 (3) | |

| CEA – median (range) | 4 (1-61) | 6.5 (0-593) | 0.048 | 5 (0-593) |

The morbidity analysis showed no difference in Clavien-Dindo morbidity between the groups (Table 1). Neither did the return to operating theatre differ between the groups (Table 1).

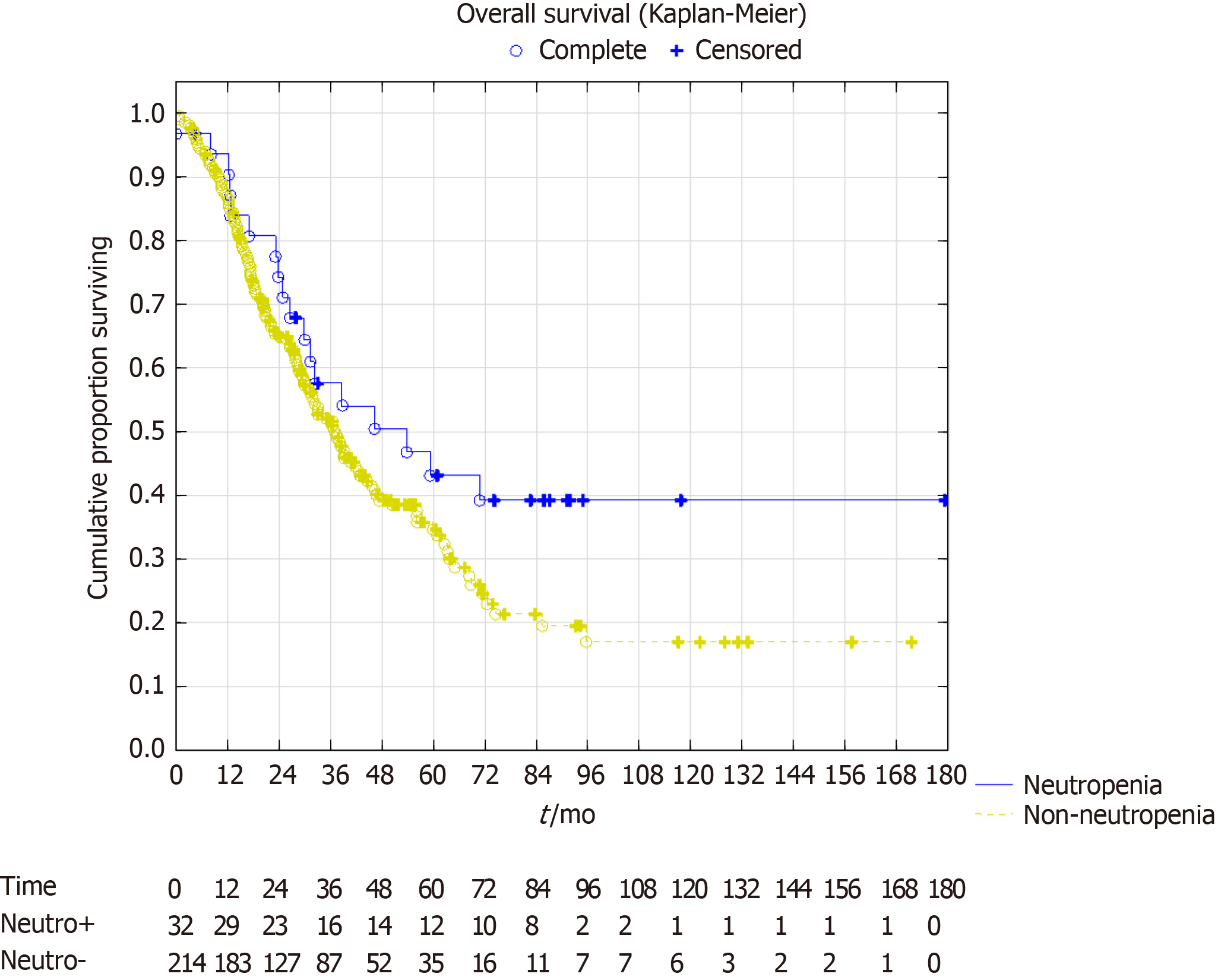

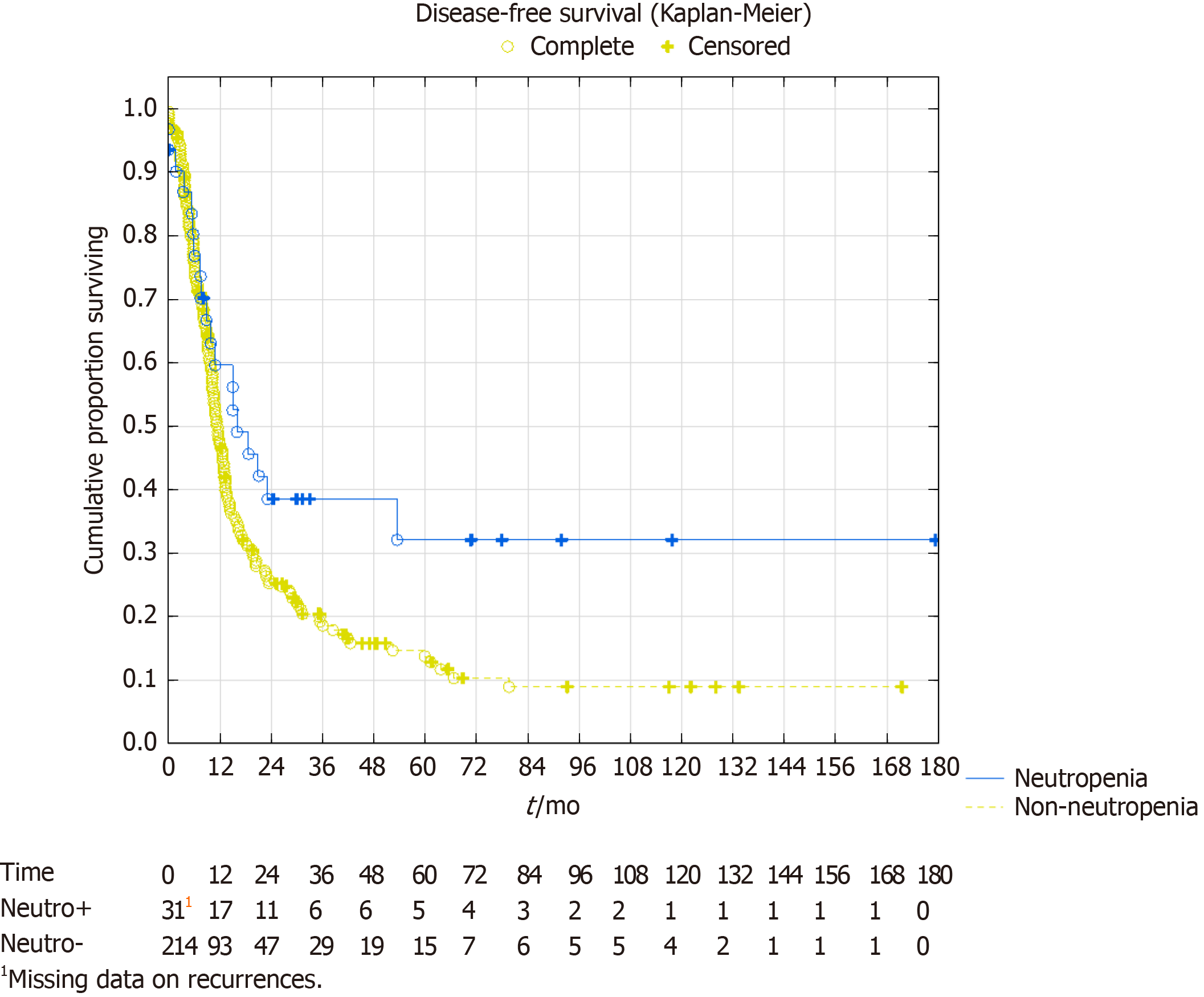

In the survival analysis, the overall survival showed a trend towards better survival in the neutropenia group. Median overall survival in the neutropenia group was 53 mo [confidence interval (CI): 30-not reached] vs 37 mo (CI: 31-45), P = 0.07. Five-year survival was 43% vs 35%, respectively with a projected 10-year survival of 39% vs 17%, respectively (Figure 2). The median disease-free survival was 16 mo (CI: 10-54) in the neutropenia group vs 11 mo (CI: 10-13) in the non-neutropenia group (Figure 3), P = 0.024. The five-year disease-free survival was 32% for the neutropenia group and 14% for the non-neutropenia group with a projected 10-year disease-free survival of 32% vs 9%, respectively.

In the multivariable Cox proportional analysis, four variables emerged as independent prognostic factors — peritoneal cancer score, completeness of cytoreduction score, treatment of concomitant liver metastases, and neutropenia. Patients with postoperative neutropenia had more than a 40% risk reduction in disease recurrence compared with patients not developing postoperative neutropenia; hazard ratio (HR): 0.58 95%CI: 0.36-0.95, P = 0.03, see Table 2. The two-variable Cox proportional hazard with time period (period 1: From February 20, 1996 to October 19, 2011, period 2: from October 19, 2011 to December 17, 2015) and neutropenia showed that both variables were significant prognostic factors for overall survival: Neutropenia yes vs no HR: 0.60 (95%CI: 0.36-0.99), P = 0.046; and time-period 2 vs 1 HR: 0.66 (95%CI: 0.47-0.93), P = 0.016.

| Univariate, hazard ratio | P value | Multivariate, hazard ratio | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 1.00 (CI: 0.99-1.01) | 0.7 | ||

| Gender male/female (n) | 1.19 (CI: 0.89-1.59) | 0.2 | ||

| Colon/Rectum | 0.81 (CI: 0.11-5.77) | 1.0 | ||

| Synchronous/metachronous | 0.90 (CI: 0.68-1.20) | 0.49 | ||

| Neoadjuvant for PM disease | 1.06 (CI: 0.79-1.41) | 0.7 | ||

| Node positive disease primary | 1.16 (CI: 0.83-1.61) | 0.52 | ||

| Poor differentiation | 1.08 (CI: 0.78-1.49) | 0.82 | ||

| PCI | 1.03 (CI: 1.01-1.04) | 0.0005 | 1.02 (CI: 1.00-1.04) | 0.033 |

| Liver metastases | 1.56 (CI: 1.06-2.30) | 0.02 | 1.52 (CI: 1.03-2.25) | 0.016 |

| CC score 0 vs 1-3 | 1.91 (CI: 1.36-2.67) | 0.0001 | 1.66 (CI: 1.12-2.46) | 0.011 |

| EPIC administration | 0.92 (CI: 0.56-1.50) | 0.73 | ||

| OX HIPEC; OXIRI HIPEC | Reference 0.74 (0.51-1.07) | 0.11 | ||

| Operating time | 1.00 (CI: 1.00-1.00) | 0.04 | 1.00 (CI: 1.00-1.00) | 0.25 |

| Any-grade neutropenia | 0.61 (CI: 0.38-0.98) | 0.02 | 0.58 (CI: 0.36-0.95) | 0.031 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy given | 1.07 (CI: 0.80-1.44) | 0.37 |

This study demonstrated a very unexpected finding and that to our knowledge has not been investigated or published previously. The hypothesis was that patients developing neutropenia would be at risk of further postoperative morbidity and decreased survival; but neither were true. The concept of HIPEC has been that it reduces systemic toxicity while retaining high concentration levels loco-regionally[10]. In fact, potential HIPEC drugs have been evaluated according to their molecular weight and the peritoneal/plasma concentration ratio[11]. Drugs with a large ratio have theoretically been more appealing to use in HIPEC as their chemotherapeutic effect has been limited to the abdominal cavity due to the blood/peritoneal barrier. In line with this reasoning, studies have sought to minimize systemic toxicity[9]. This study challenges this paradigm in a significant and unexpected way. Not only do patients that develop post-HIPEC neutropenia retain their survival rate, but they exceed that of patients not developing post-HIPEC neutropenia. As mentioned above, this was not expected in our hypothesis. Instead, it appears that neutropenia acts as an independent prognostic factor for HIPEC efficacy. This prognostic effect was independent in the multivariable analysis and was not dependent on the time period of treatment either. Presumably, neutropenia is a marker of chemotherapeutic efficacy, at least in the setting of oxaliplatin-based HIPEC. Instead of trying to avoid this morbidity, it seems to be a prognostic marker for treatment outcome and may be something to attain instead and balance out with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. One center in the French study demonstrated a good prophylactic effect with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor that lead to no severe neutropenia cases[9].

This new finding is significant in another way as well. Neutropenia is not a common postoperative complication in surgery without HIPEC. Thus, this finding represents indirect evidence of the efficacy of the HIPEC component of the CRS/HIPEC treatment combination as the HIPEC component is the main driving cause of neutropenia. This study provides a challenge to the Prodigy 7 study. It appears that further research indeed is of importance before centers start changing HIPEC regimens.

As of yet, the Prodigy 7 study has not been published and so we do not know the neutropenia rate in that study. However, in our study the oxaliplatin/irinotecan treatment group as a whole had a neutropenia rate of almost 44% whereas the oxaliplatin treatment group had just under 6% (Table 1). The Prodigy 7 study used the single intraperitoneal drug oxaliplatin treatment. It may be that single drug oxaliplatin is not an effective treatment, at least in terms of neutropenia being a preferred prognostic effect to attain. The previous French study on oxaliplatin vs oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC demonstrated statistically more neutropenia cases in the oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC combination similar to our study[9]. A finding which caused the French network to stop using this combination. Ironically, it might actually be this finding that supports the use of the oxaliplatin/irinotecan combination. The survival effect of neutropenia was never investigated in the French study. Even though, the added effect of irinotecan was found not significant for survival in our study, the sample size was much too small to be able to make any such treatment evaluation, similarly the sample size in the French study was also too small[9].

It may be that we are undertreating our patients by reducing doses and limiting the HIPEC treatment to single intraperitoneal drugs. The medical oncology community has moved quite aggressively into multi-drug treatments in the systemic setting; we believe that it might be time to do the same for HIPEC treatment. Despite neutropenia, the remaining morbidity (Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4 and return to operating theatre) was not increased for the neutropenic group. Therefore, it appears to be a safe approach even though larger studies are needed to confirm this. This approach may also provide a relevant path forward for HIPEC research in CRCPM. It is significantly easier to do a new randomized trial between oxaliplatin HIPEC vs oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC than redoing the French trial with a no-HIPEC group; something proven to be very difficult in the Nordic Peritoneal Oncology Group discussions. A HIPEC treatment intensification trial will also be able to provide evidence-based results for the continued use of HIPEC treatment in CRCPM, if a positive result is acquired. We are currently in Sweden discussing a protocol for such a trial and hope to be able to initiate this relatively soon. In preparation for this trial protocol, we will be analyzing our cohort of oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC vs oxaliplatin HIPEC in a coming study investigating these aspects more thoroughly.

The use of early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy was 2 ½ times more common in the neutropenia group (P = 0.07, Table 1). This represents also an intensification of HIPEC treatment and may also be a contributing factor in the development of neutropenia and perhaps also a relevant intensification aspect to evaluate in further studies. It may be that HIPEC intensification studies need to investigate both combination HIPEC treatment and early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatment in order to optimize and perhaps even standardize the HIPEC treatment for CRCPM in the future.

Neutropenia is a known positive prognostic factor in other colorectal cancer treatments. One recent study on colorectal cancer liver metastasis demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy induced neutropenia was an independent prognostic factor for survival after the liver surgery[12]. A relatively recent review on neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer demonstrated that high levels of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (i.e. high levels av neutrophils and low levels of lymphocytes) demonstrated a significant drop in predicted 5-year survival from 77% to 51% (even worse with liver surgery for colorectal metastases with 5-year survival 27%)[13]. There is also some preclinical evidence that neutrophil extracellular traps (NET) that form as a part of the postoperative surgical inflammatory stress may be involved in linking inflammation to cancer progression. NET production postoperatively has been shown to promote cancer cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and invasion[14]. In CRCPM, this has been poorly investigated, but a few studies have been performed. Increased preoperative white blood cell count has been proven to be an independent negative prognostic factor in CRCPM undergoing CRS and HIPEC[15]. Since 2018, two studies have been published investigating the formation of NETs in the peritoneal cavity related to peritoneal metastasis development[16,17]. NETs appear to play an important role in the peritoneal spread of colon cancer. Our theory is that systemic neutropenia is a marker of chemotherapy effect on neutrophils in general; which in turn, could plausibly correlate to an intraabdominal local neutropenia caused by the HIPEC treatment which would lead to decreased postoperative neutrophil extracellular trap formation. This hypothetical decrease in intraabdominal NETs could be the cause of the lower peritoneal relapse rate (i.e., improved disease-free survival). More research into the HIPEC treatment postoperative milieu’s effect on risk of peritoneal relapse is needed.

The main limitations of this study are the retrospective design that could introduce a selection bias for treatment intensity in the study. Patients with side-effects from previous chemotherapy may have had reduced doses, but we are unable to correct for this as motivation for dose reduction is not available in our HIPEC registry nor previous side-effects. Moreover, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may have affected the risk of developing neutropenia postoperatively. In order to evaluate the effect of these limitations, neoadjuvant chemotherapy use was evaluated in a univariate Cox regression analysis and its administration was not prognostic for disease-free survival. Therefore, even if neoadjuvant chemotherapy or dose reductions may have influenced the development of neutropenia, it cannot explain neutropenia’s positive prognostic effect. Likewise, the lack of association with other Clavien-Dindo morbidity remains. The generalizability of these results is somewhat difficult. Our cohort includes two oxaliplatin HIPEC regimens – single oxaliplatin HIPEC and oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC. A larger cohort is needed to be able to assess these HIPEC regimens separately.

In conclusion, any-grade systemic neutropenia is a positive prognostic factor for disease-free survival in CRCPM patients undergoing CRS with oxaliplatin-based HIPEC, and it occurs in 13% of cases. The occurrence of neutropenia is not associated with increased Clavien-Dindo grade 3-4 morbidity nor of return to operating theatre. Neutropenia is significantly associated with the combination treatment of oxaliplatin/irinotecan HIPEC.

Neutropenia after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) treatment of colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastases is poorly studied.

Neutropenia is currently a treatment limiting toxicity in HIPEC. Its association with the combination treatment of oxaliplatin and irinotecan HIPEC caused this intensified HIPEC regimen to be stopped. However, the implications of the neutropenia was never investigated as it was assumed to be an unwanted side-effect. More research in neutropenia is needed if more intense HIPEC treatment are to be investigated.

The objective of this study was to report on the frequency of neutropenia and its effect on Clavien-Dindo morbidity, reoperation rate, disease-free and overall survival.

An observational cohort study design was implemented using two prospectively maintained databases – Uppsala and Sydney. Kaplan-Meier and log rank tests were used as well as Cox proportional hazard models.

Neutropenia occurs in 13% of colorectal cancer patients being treated with HIPEC and is more common in the oxaliplatin + irinotecan HIPEC regimen. Neutropenia is not associated with increased Clavien-Dindo morbidity nor increased reoperation rate. It is a positive prognostic factor for disease-free survival with a clear benefit in disease-free survival (P = 0.02) as well as a trend towards a benefit in overall survival (P = 0.07).

Neutropenia may not be a treatment limiting toxicity. HIPEC intensification is possible without increasing morbidity or the reoperation rate. Unexpectedly, neutropenia was a positive prognostic factor for disease-free survival. Future studies need to confirm this unexpected finding. It suggests that neutropenia should be viewed with a different perspective – not as an unwelcomed complication, but rather as a possible predictor of treatment efficacy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Sweden

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mohamed SY, Sung WW S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, van Sloothen GW, van Tinteren H, Boot H, Zoetmulder FA. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3737-3743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1512] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cashin PH, Mahteme H, Spång N, Syk I, Frödin JE, Torkzad M, Glimelius B, Graf W. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy for colorectal peritoneal metastases: A randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cashin PH, Dranichnikov F, Mahteme H. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy treatment of colorectal peritoneal metastases: cohort analysis of high volume disease and cure rate. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bushati M, Rovers KP, Sommariva A, Sugarbaker PH, Morris DL, Yonemura Y, Quadros CA, Somashekhar SP, Ceelen W, Dubé P, Li Y, Verwaal VJ, Glehen O, Piso P, Spiliotis J, Teo MCC, González-Moreno S, Cashin PH, Lehmann K, Deraco M, Moran B, de Hingh IHJT. The current practice of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for colorectal peritoneal metastases: Results of a worldwide web-based survey of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1942-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Goéré D, Malka D, Tzanis D, Gava V, Boige V, Eveno C, Maggiori L, Dumont F, Ducreux M, Elias D. Is there a possibility of a cure in patients with colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis amenable to complete cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy? Ann Surg. 2013;257:1065-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quenet F, Elias D, Roca L, Goere D, Ghouti L, Pocard M, Facy O, Arvieux C, Lorimier, Denis Pezet G, Marchal F, Loi V, Meeus P, De Forges H, Stanbury T, Paineau J, Glehen O. A UNICANCER phase III trial of hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC): PRODIGE 7. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ceelen W. HIPEC with oxaliplatin for colorectal peritoneal metastasis: The end of the road? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:400-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Pinto A, Pocard M. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin and mitomycin C for colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases: A systematic review of the literature. Pleura Peritoneum. 2019;4:20190006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Quenet F, Goéré D, Mehta SS, Roca L, Dumont F, Hessissen M, Saint-Aubert B, Elias D. Results of two bi-institutional prospective studies using intraperitoneal oxaliplatin with or without irinotecan during HIPEC after cytoreductive surgery for colorectal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg. 2011;254:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chalret du Rieu Q, White-Koning M, Picaud L, Lochon I, Marsili S, Gladieff L, Chatelut E, Ferron G. Population pharmacokinetics of peritoneal, plasma ultrafiltrated and protein-bound oxaliplatin concentrations in patients with disseminated peritoneal cancer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion of oxaliplatin following cytoreductive surgery: correlation between oxaliplatin exposure and thrombocytopenia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:571-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pestieau SR, Belliveau JF, Griffin H, Stuart OA, Sugarbaker PH. Pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal oxaliplatin: experimental studies. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:106-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen Q, Wu C, Zhao H, Wu J, Zhao J, Bi X, Li Z, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Cai J. Neo-adjuvant Chemotherapy-Induced Neutropenia Is Associated with Histological Responses and Outcomes after the Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:659-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Haram A, Boland MR, Kelly ME, Bolger JC, Waldron RM, Kerin MJ. The prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:470-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tohme S, Yazdani HO, Al-Khafaji AB, Chidi AP, Loughran P, Mowen K, Wang Y, Simmons RL, Huang H, Tsung A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote the Development and Progression of Liver Metastases after Surgical Stress. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1367-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cashin PH, Graf W, Nygren P, Mahteme H. Patient selection for cytoreductive surgery in colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis using serum tumor markers: an observational cohort study. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1078-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kanamaru R, Ohzawa H, Miyato H, Yamaguchi H, Hosoya Y, Lefor AK, Sata N, Kitayama J. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Generated by Low Density Neutrophils Obtained from Peritoneal Lavage Fluid Mediate Tumor Cell Growth and Attachment. J Vis Exp. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kanamaru R, Ohzawa H, Miyato H, Matsumoto S, Haruta H, Kurashina K, Saito S, Hosoya Y, Yamaguchi H, Yamashita H, Seto Y, Lefor AK, Sata N, Kitayama J. Low density neutrophils (LDN) in postoperative abdominal cavity assist the peritoneal recurrence through the production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). Sci Rep. 2018;8:632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |