Published online Dec 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i12.1151

Peer-review started: March 4, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: September 18, 2019

Accepted: October 14, 2019

Article in press: October 14, 2019

Published online: December 15, 2019

Processing time: 282 Days and 11.4 Hours

It has been recognized for a long time that gastric cancer behavior and outcomes might be different between patients living in Asian countries vs patients living in Western countries. It is not clear if these differences would persist between patients of Asian ancestry and patients of other racial subgroups within the multiethnic communities of North America. The current study hypothesizes that these differences will present within North American multiethnic communities.

To evaluate the impact of race on survival outcomes of non-metastatic gastric cancer patients in the United States.

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (CALGB 80101 study) that evaluated two adjuvant chemoradiotherapy schedules following resection of non-metastatic gastric cancer. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank testing were utilized to explore the overall and disease-free survival differences according to the race of the patients. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were then used to explore factors affecting overall and disease-free survivals.

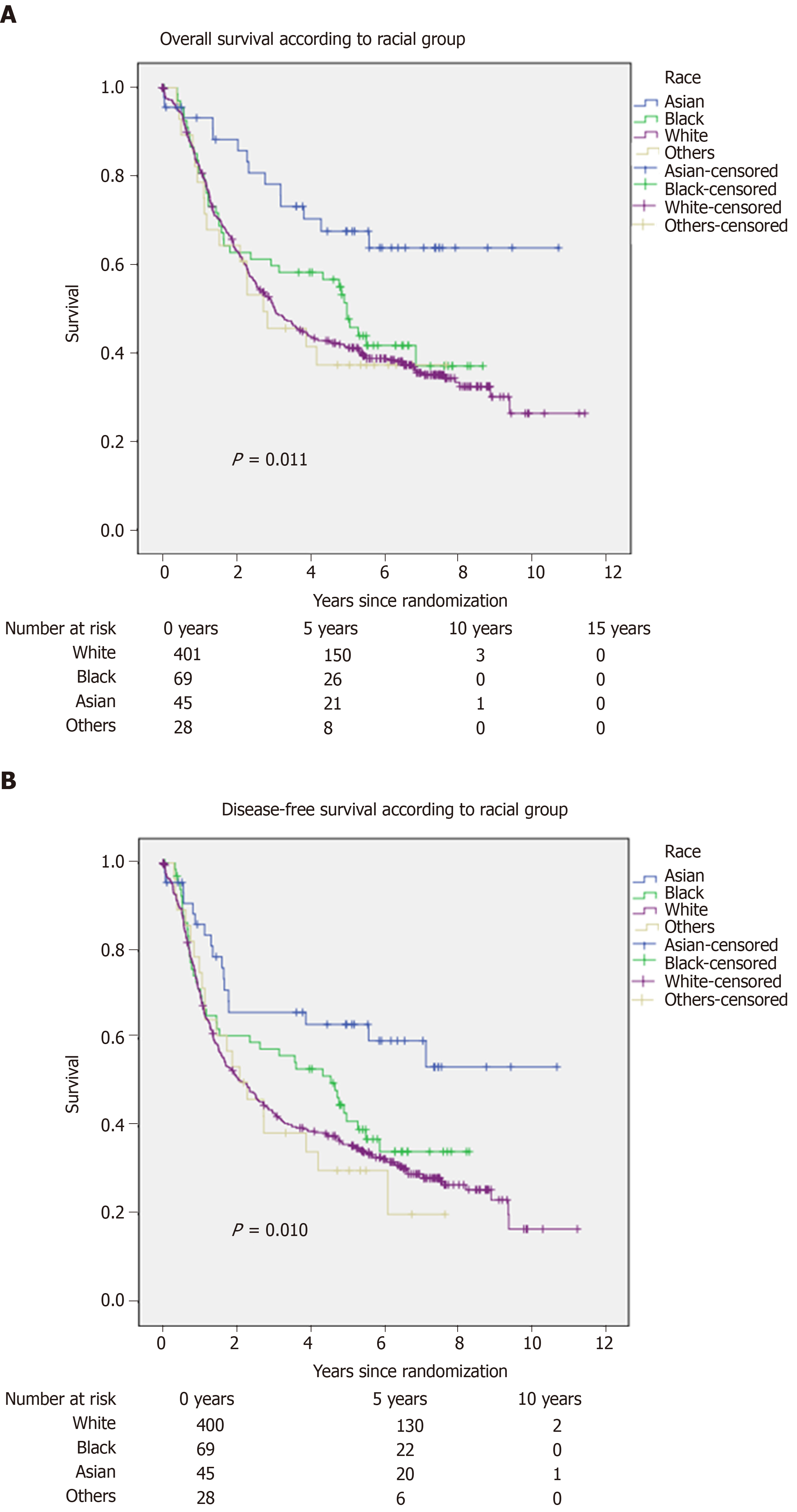

A total of 546 patients were included in the current analysis. Of which, 73.8% have white race (vs 12.8% black Americans and 8.2% Asian Americans). Using Kaplan-Meier analysis/log-rank testing, Asian Americans appear to have better overall and disease-free survival outcomes compared to other United States racial groups (White Americans, Black Americans, and other racial groups) (P = 0.011; P = 0.010; respectively). Moreover, in an adjusted multivariate model, Asian American race seems to be associated with better overall and disease-free survival (hazard ratio: 0.438; 95% confidence interval: 0.254-0.754), P = 0.003; hazard ratio: 0.460; 95% confidence interval: 0.280-0.755, P = 0.002; respectively).

Asian American patients with non-metastatic gastric cancer have better overall and disease-free survival compared to other racial groups in the United States. Further preclinical and clinical research is needed to clarify the reasons behind this observation.

Core tip: Asian American patients with non-metastatic gastric cancer have better overall and disease-free survival compared to other racial groups in the United States. These findings are thought-provoking for the potential biological mechanisms underlying this observation as well as the potential therapeutic implications of these findings.

- Citation: Abdel-Rahman O. Asian Americans have better outcomes of non-metastatic gastric cancer compared to other United States racial groups: A secondary analysis from a randomized study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(12): 1151-1160

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i12/1151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i12.1151

Gastric cancer is one of the most common causes of mortality and morbidity ascribed to cancer diagnosis worldwide[1]. A considerable geographical variation exists with regards to its etiology as well as its incidence[2]. Compared to Western countries, many Asian countries have a higher incidence of gastric cancer[3].

It has been recognized for a long time that gastric cancer behavior and outcomes might be different between patients living in Asian countries vs patients living in Western countries[4]. Possible reasons for these differences might be related to differences in etiology, biology, stage at presentation, or therapeutic approaches between the two categories of patients[5]. However, it is not yet fully clear if these differences persist between patients of Asian ancestry and patients of other racial subgroups within the multiethnic communities of North America.

A few previously published retrospective studies have suggested a difference between Asian American and other racial groups in the United States[6,7]. These studies were, however, criticized because of the potential -unaccounted for- confounders that frequently accompany retrospective studies. This made their conclusions far from decisive.

To provide a better answer for this question, there is a need to approach this question within the context of a prospectively collected dataset that adequately reports on baseline demographic characteristics of included patients as well as treatments received. Project Data Sphere (PDS) provides an ideal opportunity to tackle this question within the context of a controlled clinical trial[8]. The CALGB 80101 trial (NCT00052910), which evaluated two adjuvant chemoradiotherapy schedules for resected gastric cancer, was downloaded from the PDS platform to tackle this research question.

The current study aims at evaluating the impact of race on survival outcomes of non-metastatic gastric cancer patients in the United States treated with surgery plus adjuvant treatment.

This is a randomized phase III study evaluating two different adjuvant chemoradiotherapy schedules following resection of non-metastatic gastric cancer. These two schedules are: (1) 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin for 5 d on cycles 1,3,4 and 5-fluorouracil continuous intravenous infusion for 5 wk in cycle 2 concurrent with radiation therapy; and (2) Epirubicin/cisplatin/5-fluorouracil for cycles 1,3,4 and 5-fluorouracil continuous intravenous infusion for 5 wk in cycle 2 concurrent with radiation therapy. The start date of the study was in December 2002, and the primary completion date was in June 2012. Patients were included in this study regardless of the extent of nodal dissection. Detailed eligibility, methods, and primary results of this study were published elsewhere. The records of a total of 546 patients were available from the included study[9].

The following information was collected (where available) from each of the included participants in the current study: Age at diagnosis, sex, race, ethnicity, performance status, history of prior cancer, T stage, N stage, lymph node ratio (defined as the ratio between positive and examined lymph nodes), histologic grade, primary tumor site, assigned treatment arm, and reason of stoppage of treatment. Type of lymph node dissection (D1 vs D2) was not available in the downloaded study datasets.

Primary endpoints for the current study include overall survival (defined as the time from randomization till death of any reason) and disease-free survival (defined as the time from randomization till death or progressive disease diagnosis).

Descriptive statistics were initially utilized to explore frequencies and distribution of different baseline parameters in the studied cohort. Chi-Squared testing was then used to explore the distribution of baseline characteristics between Asian Americans and other racial subgroups in the United States.

Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank testing were utilized to explore the overall and disease-free survival differences according to the race of the patients. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were then used to explore factors affecting overall and disease-free survivals. Factors with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were subsequently included into multivariate analysis. SPSS statistics (version 20; IBM; Armonk, NY, United States) was used to execute all statistical procedures. P < 0.05 was used as an indicator of statistical significance.

Among the included patients, 46.2% were ≥ 60-years-old, 67.9% were males, 73.8% have white race (vs 12.8% black Americans and 8.2% Asian Americans), and only a minority of patients were of Hispanic ethnicity (9.9%). Almost half of the patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0, only 4% of patients had a history of another cancer, and most patients had node-positive disease. The study cohort was almost equally divided between the two treatment arms, and most patients (65.8%) completed the planned course of treatment (Table 1).

| Parameter | n (%) |

| Age | |

| < 60 yr | 294 (53.8) |

| ≥ 60 yr | 252 (46.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 371 (67.9) |

| Female | 175 (32.1) |

| Race | |

| White | 403 (73.8) |

| Black | 70 (12.8) |

| Asian | 45 (8.2) |

| Others | 28 (5.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 54 (9.9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 445 (81.5) |

| Unknown | 47 (8.6) |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 276 (50.5) |

| 1 | 257 (47.1) |

| 2 | 13 (2.4) |

| History of prior cancer | |

| Yes | 22 (4) |

| No | 516 (94.5) |

| Unknown | 8 (1.5) |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 33 (6) |

| T2 | 219 (40.1) |

| T3 | 259 (47.4) |

| T4 | 23 (4.2) |

| Unknown | 12 (2.2) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 77 (14.1) |

| N1 | 312 (57.1) |

| N2 | 105 (19.2) |

| N3 | 34 (6.2) |

| Unknown | 18 (3.3) |

| Lymph node ratio (mean; SD) | 0.32; 0.307 |

| Histologic grade | |

| Grade 1 | 15 (2.7) |

| Grade 2 | 139 (25.5) |

| Grade 3 | 360 (65.9) |

| Grade 4 | 17 (3.1) |

| Unknown | 15 (2.8) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| GEJ/ cardia/ fundus | 208 (38.1) |

| Body/antrum/ pylorus | 161 (29.5) |

| Others, NOS | 177 (32.4) |

| Treatment arm | |

| 5FU/LCV + RT | 280 (51.3) |

| ECF + RT | 266 (48.7) |

| Completion Of treatment | |

| Completed as planned | 359 (65.8) |

| Stopped because of adverse events | 64 (11.7) |

| Stopped because of progression/death | 33 (6) |

| Stopped because of other reasons (e.g., consent withdrawal) | 90 (16.5) |

Comparing Asian Americans with other racial groups, Asian Americans were less likely to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 0 (48.9% vs 50.7%; P < 0.001). On the other hand, there was no difference between Asian Americans and other racial groups with regards to sex (P = 0.233), age group (P = 0.810), history of prior cancer (P = 0.873), histologic grade (P = 0.067), T stage (P = 0.614), N stage (P = 0.867), or assigned treatment arm (P = 0.737) (Table 2).

| Variable | Asian Americans, 45 patients | Other patients, 501 patients | P value |

| Age | 0.810 | ||

| < 60 yr | 25 (55.6) | 269 (53.7) | |

| ≥ 60 yr | 20 (44.4) | 232 (46.3) | |

| ECOG Performance score | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 22 (48.9) | 254 (50.7) | |

| 1 | 18 (40) | 239 (47.7) | |

| 2 | 5 (11.1) | 8 (1.6) | |

| Sex | 0.233 | ||

| Male | 27 (60) | 344 (68.7) | |

| Female | 18 (40) | 157 (31.3) | |

| History of prior cancer | 0.873 | ||

| Yes | 2 (4.5) | 20 (4) | |

| No | 42 (95) | 474 (95.5) | |

| Unknown | 1(0.5) | 7 (0.5) | |

| T stage | 0.614 | ||

| T1-2 | 20 (44.4) | 232 (46.3) | |

| T3-4 | 24 (53.4) | 258 (51.5) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2.2) | 11 (2.2) | |

| N stage | 0.867 | ||

| N 0 | 8 (17.8) | 69 (13.8) | |

| N 1-3 | 35 (77.8) | 416 (83) | |

| Unknown | 2 (4.4) | 16 (3.2) | |

| Histologic grade | 0.067 | ||

| Grade 1-2 | 6 (11.7) | 148 (29) | |

| Grade 3-4 | 38 (86.3) | 339 (68) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 14 (3) | |

| Treatment arm | 0.737 | ||

| 5FU/LCV + RT | 22 (48.9) | 258 (51.5) | |

| ECF + RT | 23 (51.1) | 243 (48.5) |

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis/log-rank testing, Asian Americans appear to have better overall and disease-free survival outcomes compared to other United States racial groups (White Americans, Black Americans, and other racial groups) (P = 0.011; P = 0.010; respectively) (Figure 1).

Univariate analysis was then utilized to explore factors affecting overall and disease-free survival in the studied cohort. The following factors were evaluated in the univariate analysis: Age at diagnosis, race, performance status, sex, ethnicity, history of prior cancer, T stage, lymph node ratio, histologic grade, tumor site, and treatment arm. For both endpoints, the following factors were significant in univariate analysis (P < 0.05): T stage, lymph node ratio, primary tumor site, and race. When including these factors in a multivariate analysis for overall survival, the following factors were predictive of better overall survival: Asian American race (hazard ratio (HR) vs white race: 0.438; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.254-0.754 , P = 0.003), lower T stage (HR for T4 vs T1: 3.807; 95%CI:1.731-8.361; P = 0.001), lower lymph node ratio (HR with increasing lymph node ratio: 3.004; 95%CI: 2.154-4.190; P < 0.001), and distal site of tumor primary (HR for proximal vs distal tumor: 1.523; 95%CI: 1.138-2.037; P = 0.005). Likewise, when including these factors in a multivariate analysis for disease-free survival, the following factors were predictive of better disease-free survival: Asian American race (HR vs white race: 0.460: 95%CI: 0.280-0.755, P = 0.002), lower T stage (HR for T4 vs T1: 3.990; 95%CI: 1.885-8.443; P < 0.001), lower lymph node ratio (HR with increasing lymph node ratio: 2.471; 95%CI: 1.801-3.390; P < 0.001), and distal site of tumor primary (HR for proximal vs distal tumor: 1.367; 95%CI: 1.042-1.793; P = 0.024) (Table 3).

| Parameter | Overall survival | Disease-specific survival | ||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.020 (0.717-1.453) | 0.911 | 0.962 (0.684-1.353) | 0.825 |

| Asian | 0.438 (0.254-0.754) | 0.003 | 0.460 (0.280-0.755) | 0.002 |

| Lymph node ratio, continuous | 3.004 (2.154-4.190) | < 0.001 | 2.471 (1.801-3.390) | < 0.001 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| T2 | 1.680 (0.878- 3.215) | 0.117 | 1.895 (1.020-3.520) | 0.043 |

| T3 | 2.517 (1.321-4.798) | 0.005 | 3.042 (1.643-5.632) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 3.807 (1.731-8.361) | 0.001 | 3.990 (1.885-8.443) | < 0.001 |

| Primary site | ||||

| Body/antrum/pylorus | Reference | Reference | ||

| GEJ/cardia/fundus | 1.523 (1.138-2.037) | 0.005 | 1.367 (1.042-1.793) | 0.024 |

The current study evaluated the impact of racial affiliation on the outcomes of non-metastatic United States gastric cancer patients. It suggests that Asian Americans with non-metastatic gastric cancer have better overall and disease-free survival compared to other racial groups in the United States.

These findings are consistent with previously reported population-based studies that suggested that United States gastric cancer patients of Asian Ancestry have better survival outcomes compared to other racial groups[10,11]. However, the current study is unique in being based on a controlled dataset that was collected in the context of a well-conducted randomized study.

Previous multinational comparisons have also suggested that Asian gastric cancer patients have better survival outcomes compared to other gastric cancer patients from other ethnic backgrounds[12,13]. It was previously postulated that this might be the result of an earlier stage at diagnosis and/or more aggressive surgical approach (particularly with regards to D2 dissection approach)[14]. However, the current study suggests that such differences cannot be explained by these factors alone. Asian American patients were treated in North America (according to the same surgical standard of other racial groups), and the current study does not show clear evidence of a uniquely earlier stage at diagnosis. It is not known, however, if patients labeled in the current study as Asian Americans were of first or subsequent generation of Asian Americans. Thus, one cannot exclude completely the potential contribution of environmental/ social differences between the East and the West. Additional factors that might explain these findings are potential biological differences between Asian and Caucasian patients with gastric cancer. Previous studies suggested that the predominant biological/ topographical subtype of gastric cancer among Asian patients might be different from the one that is prevalent among Caucasian patients[15]. Likewise, the variable role of Helicobacter Pylori infection as a carcinogenic factor between different ethnic groups might also be a factor here[16]. Further studies are needed to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

The current study has several limitations that need to be appreciated: Foremost, although the current study is based on a randomized prospective study, the specific question of the impact of race on outcomes was not a priori question within this study but rather an exploratory subsequent question. Thus, the current study is still a retrospective study of a prospectively collected dataset. Second, the current study contains a relatively small number of patients; confirmation of these findings in a larger prospective cohort is needed. These weaknesses need to be weighed against the clear strengths of the current study; most notably, the reliance on controlled well-conducted clinical trial dataset that provides a far more credible comparison compared to traditional retrospective, population-based studies.

The current study might also be informative for future research efforts of gastric cancer both in North America as well as in other parts of the world. Future randomized studies involving gastric cancer patients in North America should include a priori subgroup analysis for Asian Americans vs other racial groups. Moreover, additional exploration of the outcomes of first-generation vs second and subsequent generation Asian Americans are needed to dissect possible environmental/ social factors from potential biological differences. Likewise, a comparison of the outcomes of Asian Americans vs Asians living in Asian countries within a multinational context would also be useful for the same purpose. Moreover, national and international consortia working on the genetic mapping of gastric cancer should also pay additional attention to the possible differences in gastric cancer behavior (and possibly biology) among different ethnic groups.

The current study also further confirms the current practice of requiring confirmation of clinical trial results conducted exclusively on Asian patients (e.g., Japanese trials) prior to generalization to western patients (and vice versa). The clear differences in outcomes of Asian vs Caucasian patients (treated within the same clinical trial/ health care system) mandate greater caution prior to the generalization of clinical trial results.

It should also be noted that the term “Asian Americans” includes quite a broad category of ethnicities, and the outcomes of gastric cancer might be variable among these ethnicities as well. Unfortunately, the current study dataset does not differentiate between different Asian American ethnic subgroups. This is another area of research that needs to be tackled in the future.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that Asian American patients with non-metastatic gastric cancer have better overall and disease-free survival compared to other racial groups in the United States. Further preclinical and clinical research is needed to clarify the reasons behind this observation.

Gastric cancer behavior and outcomes might be different between patients living in Asian countries vs patients living in Western countries. It is not clear if these differences would persist between patients of Asian ancestry and patients of other racial subgroups within the multiethnic communities of North America.

This study hypothesizes that these differences will present within North American multiethnic communities.

To evaluate the impact of race on survival outcomes of non-metastatic gastric cancer patients in the United States.

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (CALGB 80101 study) that evaluated two adjuvant chemoradiotherapy schedules following resection of non-metastatic gastric cancer. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank testing were utilized to explore the overall and disease-free survival differences according to the race of the patients. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were then used to explore factors affecting overall and disease-free survival.

A total of 546 patients were included in the current analysis. Of which, 73.8% have white race (vs 12.8% black Americans and 8.2% Asian Americans). Using Kaplan-Meier analysis/log-rank testing, Asian Americans appear to have better overall and disease-free survival outcomes compared to other United States racial groups (White Americans, Black Americans and other racial groups) (P = 0.011; P = 0.010; respectively). Moreover, in an adjusted multivariate model, Asian American race seems to be associated with better overall and disease-free survival (hazard ratio: 0.438; 95%CI: 0.254-0.754), P = 0.003; hazard ratio: 0.460; 95%CI: 0.280-0.755, P = 0.002; respectively).

Asian American patients with non-metastatic gastric cancer have better overall and disease-free survival compared to other racial groups in the United States. Further preclinical and clinical research is needed to clarify the reasons behind this observation.

The findings of this study are thought-provoking for the potential biological mechanisms underlying this observation as well as the potential therapeutic implications of these findings.

The current study is based on a clinical trial dataset downloaded from Projectdatasphere.org. Neither PDS nor the authors of the original research are responsible for the findings in the current analysis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mikulic D S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1159] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 120.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guggenheim DE, Shah MA. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483-4490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Irino T, Takeuchi H, Terashima M, Wakai T, Kitagawa Y. Gastric Cancer in Asia: Unique Features and Management. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:279-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Branicki FJ, Chu KM. Gastric cancer in Asia: progress and controversies in surgical management. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, Deapen D, Ward E. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barzi A, Yang D, Wu AH, Wu AH, Stram DO. Gastric Cancer Among Asian Americans. Wu AH, Stram DO. Cancer Epidemiology Among Asian Americans. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2016; 249-269. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Project Data Sphere. Life science consortium. Available from: https://www.projectdatasphere.org/projectdatasphere/html/home. |

| 9. | Fuchs CS, Niedzwiecki D, Mamon HJ, Tepper JE, Ye X, Swanson RS, Enzinger PC, Haller DG, Dragovich T, Alberts SR, Bjarnason GA, Willett CG, Gunderson LL, Goldberg RM, Venook AP, Ilson D, O'Reilly E, Ciombor K, Berg DJ, Meyerhardt J, Mayer RJ. Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy With Epirubicin, Cisplatin, and Fluorouracil Compared With Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy With Fluorouracil and Leucovorin After Curative Resection of Gastric Cancer: Results From CALGB 80101 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3671-3677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mailey B, Sun CL, Artinyan A, Prendergast C, Pigazzi A, Ellenhorn J, Bhatia S, Kim J. Asian-Americans Have Superior Outcomes for Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancer Symposium. 2009;Jan 15-17; San Francisco, CA, 2009; 16-17. |

| 11. | Jin H, Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Altekruse SF. Examining the gastric cancer survival gap between Asians and whites in the United States. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:573-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Merchant SJ, Li L, Kim J. Racial and ethnic disparities in gastric cancer outcomes: more important than surgical technique? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11546-11551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Davidson M, Chau I. Variations in outcome for advanced gastric cancer between Japanese and Western patients: a subgroup analysis of the RAINBOW trial. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sasako M, Inoue M, Lin JT, Khor C, Yang HK, Ohtsu A. Gastric Cancer Working Group report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40 Suppl 1:i28-i37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shah MA, Cutsem EV, Kang Y-K, Dakhil SR, Satoh T, Chin K, Bang Y-J, Bu L, Bilic G, Ohtsu A. Survival analysis according to disease subtype in AVAGAST: First-line capecitabine and cisplatin plus bevacizumab (bev) or placebo in patients (pts) with advanced gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:5-5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Correa P, Piazuelo MB. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. US Gastroenterol Hepatol Rev. 2011;7:59-64. [PubMed] |