Published online Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.898

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: September 2, 2019

Accepted: September 13, 2019

Article in press: September 13, 2019

Published online: October 15, 2019

Processing time: 218 Days and 19.6 Hours

Tumor budding, is a promising prognostic hallmark in many cancers, and can help us better assess the degree of malignancy in gastric cancer (GC) and in colorectal cancer. In the past few years, several articles on the relationship between tumor budding and GC have been published, but different results have been observed. As the relationship between tumor budding and GC remains controversial, we integrated the data from 7 eligible studies to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis.

To systematically evaluate the prognostic and pathological impact of tumor budding in GC.

Literature searches were conducted in the PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE and Web of Science databases, and 7 cohort studies involving 2178 patients met our criteria and included in the analysis. The patients were divided into those with high-grade tumor budding and those with low-grade tumor budding, and the cut-off values for tumor budding varied across the included studies. The hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the impact of tumor budding on overall survival (OS) in GC patients. The odds ratios (ORs) with 95%CIs were used to determine the correlation between tumor budding and pathological parameters (tumor stage, tumor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, lymph node metastasis) of GC.

Seven studies involving 2178 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The combined ORs suggested that high-grade tumor budding was significantly associated with tumor stage (OR = 6.63, 95%CI: 4.01-10.98, P < 0.01), tumor differentiation (OR = 3.74, 95%CI: 2.68-5.22, P < 0.01), lymphovascular invasion (OR = 7.85, 95%CI: 5.04-12.21, P < 0.01), and lymph node metastasis (OR = 5.75, 95%CI: 3.20-10.32, P < 0.01). Moreover, high-grade tumor budding predicted a poor 5-year OS (HR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.53-2.05, P < 0.01) in patients with GC and an adverse 5-year OS (HR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.45-2.42, P < 0.01) in patients with intestinal-type GC.

High-grade tumor budding suggested a poor prognosis in patients with GC or intestinal-type GC.

Core tip: Tumor budding is known to be a specific pathological marker in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer and squamous cell carcinoma. However, the prognostic value of tumor budding in patients with gastric cancer (GC) has not been extensively studied and remains controversial. This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the prognostic value of tumor budding in GC. The findings suggest that tumor budding is closely related to tumor stage, tumor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastasis in GC.

- Citation: Guo YX, Zhang ZZ, Zhao G, Zhao EH. Prognostic and pathological impact of tumor budding in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(10): 898-908

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i10/898.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.898

Gastric cancer (GC), including cardia and noncardia GC, is a highly malignant cancer worldwide with over 1000000 new cases in 2018 and an estimated 783000 deaths (equating to 1 in every 12 deaths globally), making it the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death[1]. Despite the use of multidisciplinary treatments, the 5-year survival rate for GC patients is reported to be 20%-40%[2].

Currently, the TNM staging system is considered the most robust system to predict the prognosis of patients with GC. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria, pathological staging of GC includes: depth of tumor stage (T), number of lymph nodes involved (N), and presence of distant metastasis (M)[3,4].

However, due to the pursuit of individualized diagnosis and medical treatment, the outcome parameters for patients with GC remain inadequate and inaccurate. In the future, the stratification of GC will depend on biochemical, morphological, molecular biological and treatment-related parameters to improve accuracy.

Thus, it is imperative to find available markers to precisely estimate the pathological diagnosis and prognosis of GC. One such marker is tumor budding, defined as the presence of single cancer cells or small clusters of fewer than five cells at the invasive front[5-7], and has been officially recognized by the Union for International Cancer Control as an additional prognostic factor in colorectal cancers. Moreover, tumor budding has recently been included in the guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis in Europe[8] and Japan[9], highlighting the increased use of this parameter in clinical practice.

Importantly, tumor budding has been reported to be a promising prognostic hallmark in many other cancers[10-13], including GC[14,15]. However, the prognostic value of tumor budding in GC has not been fully clarified. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between tumor budding and 5-year overall survival (OS) in patients with GC as well as the clinicopathological parameters.

We systematically retrieved all studies that evaluated the relationship between tumor budding and the outcome of patients with GC using the PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases. The search terms were as follows: “tumor budding”, “tumour budding”, “tumor-cell dissociation”, “gastric cancer”, “gastric carcinoma”, “gastric neoplasm”, “stomach cancer” and “prognosis”, “prognostic” and “survival”. The reference lists of all eligible studies were also assessed manually.

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) The study demonstrated a relationship between tumor budding and OS or pathological features of GC; (2) Sufficient information was provided to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs); and (3) Only English language literature was included.

The following articles were excluded: (1) Reviews, conference proceedings, abstracts, expert opinions, and case reports; (2) Studies with no available data on tumor budding in GC; (3) Overlapping studies; and (4) Nonhuman studies.

Two authors (Guo YX and Zhang ZZ) independently extracted information using a standardized form. The following characteristics were retrieved: First author’s name, year of publication, country of patients’ origin, the number of patients, staining methods, cut-off points for tumor budding, survival data and pathological data. If the survival data were not presented in the article, we obtained the data using Kaplan–Mhigeier curves according to Parmar et al[16]. The quality of each study was tested using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale.

All statistical analysis was carried out using STATA 15.0 software. The impact of tumor budding on OS was quantitatively evaluated by HRs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The most common method was used to obtain the HR and 95%CI directly from the paper or calculate them using the parameters provided in the manuscript. Otherwise, we extracted results from the Kaplan-Meier curves with Engauge Digitizer according to the methods reported by Parmar et al[16].

We extracted and combined data on tumor budding and several pathological characteristics, including tumor stage (I-II/III-IV), tumor differentiation (well/moderate and poor), lymphatic metastasis (absent/present), and lymphovascular invasion (absent/present), related to GC in each study. For these data, the Mantel-Haenszel ORs with their 95%CIs were calculated and combined to provide the effective value.

X2 and I2 tests were used to measure heterogeneity between each article. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and I2 < 50% indicated no heterogeneity between studies. If there was no heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), a fixed-effects model was used. Otherwise, a random-effects model was applied (I2 > 50%). Subgroup analysis was used to determine the source of heterogeneity.

Statistical significance is expressed as P < 0.05 or < 0.01 (P > 0.05 are denoted).

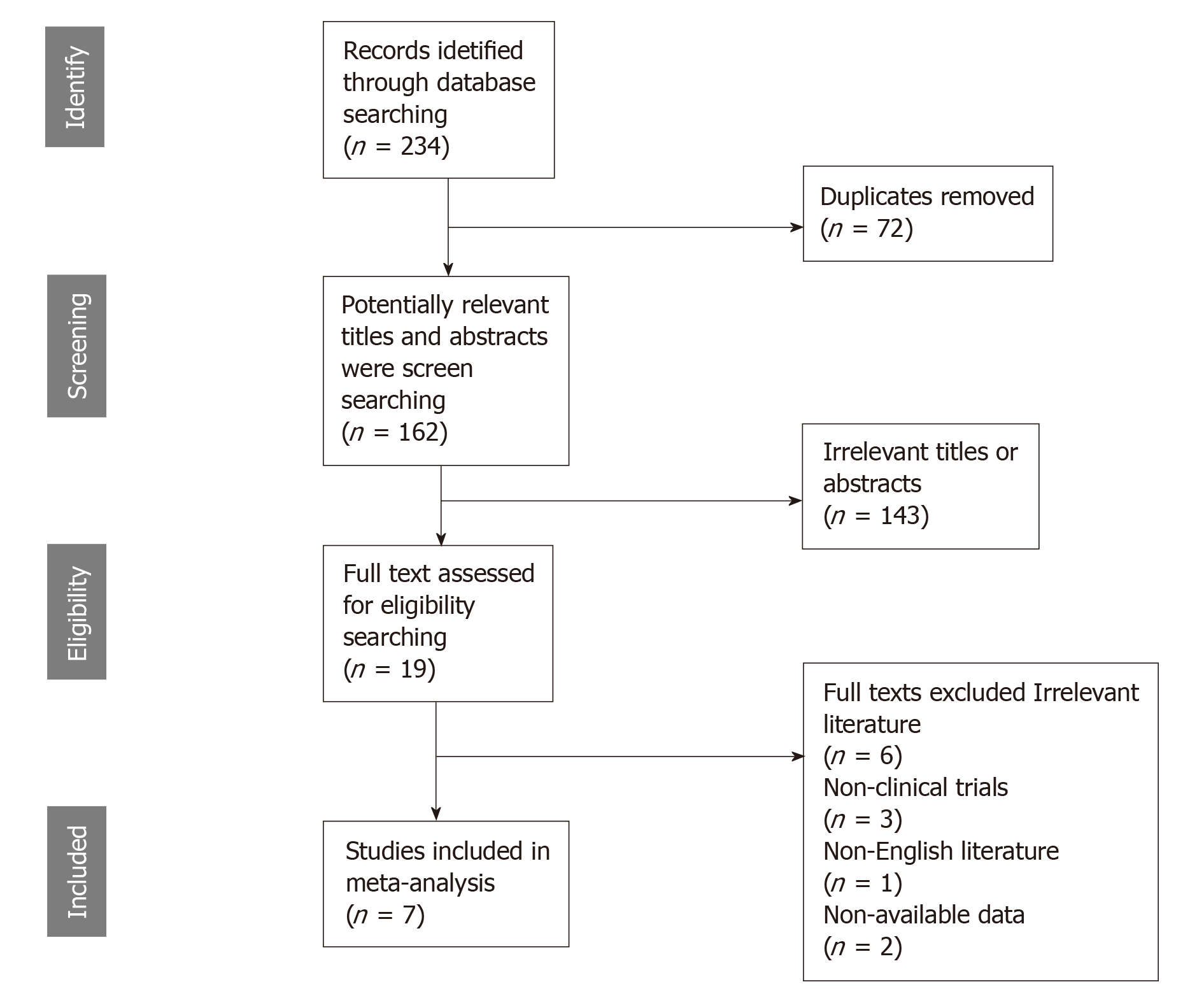

The preliminarily selected literature included 234 articles from the PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Web of Science databases. After checking the titles and abstracts, irrelevant studies were excluded, and 19 potential studies were evaluated by intensive reading. As a result, 12 of these studies were excluded for the following reasons: the data could not be extracted from the study, non-English literature, and non-clinical trials. The search method for the studies included in this meta-analysis is presented in Figure 1. Finally, seven studies were selected for this analysis. The studies were conducted in seven countries (China, Japan, Turkey, Germany, Finland, the United States and the United Kingdom) and were published between 1992 and 2019. Six studies were on GC, and one study was related to gastroesophageal junction cancer. The main characteristics of the eligible studies are shown in Table 1. The HRs data from 3 studies were extracted from the original univariate analysis directly, while the data from the other 2 studies were estimated from survival curves. Evaluation by the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale showed that 6 (85.7%) of the studies had quality scores > 5, indicating that the included studies were of good quality.

| Author | Year | Country | Cases | Cancer | Stage | Staining | Cut off | Microscopic magnification | Survival analysis | Newcastle-Ottawa score |

| Gabbert et al[14] | 1992 | Germany | 445 | GC | I-IV | HE | 5 buds | NA | OS | 7 |

| Brown et al[17] | 2010 | UK | 356 | EGJA | I-IV | HE | 5 buds | NA | OS | 7 |

| Tanaka et al[18] | 2014 | Japan | 320 | GC | I-IV | HE | Median | × 400 | OS | 8 |

| Gulluoglu et al[19] | 2015 | Turkey | 126 | GC | I | HE | 5 buds | × 400 | NA | 4 |

| Che et al[20] | 2017 | China | 296 | GC | I-IV | HE | 5 buds | × 400 | OS | 8 |

| Olsen et al[21] | 2017 | USA | 52 | GC | I-IV | HE | Median | × 200 | PFS | 6 |

| Kemi et al[15] | 2019 | Finland | 583 | GC | I-IV | HE | 10 buds | × 400 | OS | 8 |

We evaluated the correlation between tumor budding and depth of tumor stage, tumor differentiation status, lymph vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis of GC.

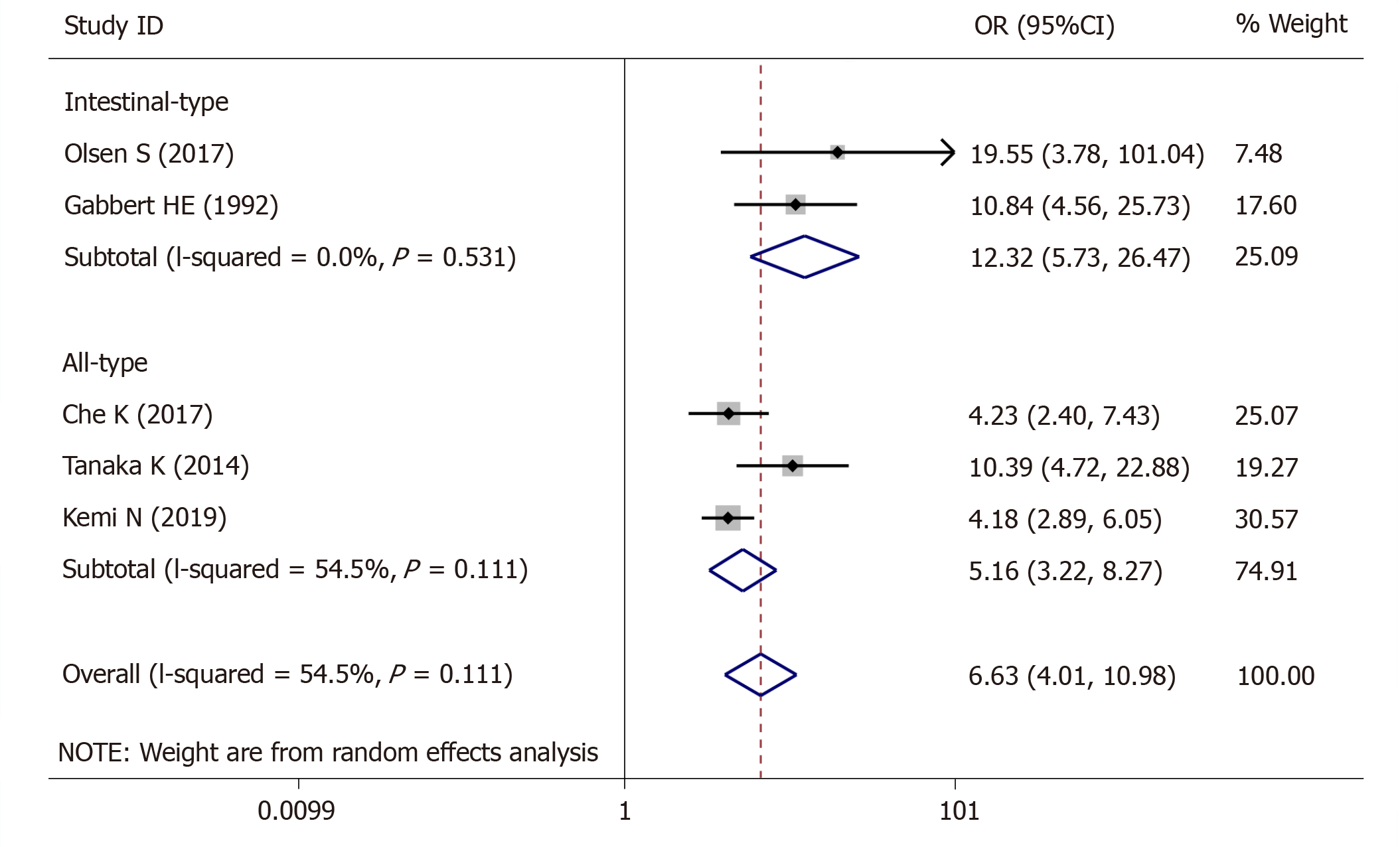

For tumor stage, 5 studies (1423 patients) were qualified for the meta-analysis and there was statistically significant association between high-grade tumor budding and tumor stage (OR = 6.63, 95%CI: 4.01-10.98, P < 0.01) (Figure 2). The test for heterogeneity was significant using the random-effects model (Ι² = 60.5%, Ρ = 0.038) (Figure 2). Furthermore, when the subgroups were stratified by the type of GC, the heterogeneity of studies with intestinal-type GC (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.531) (Figure 2) was effectively eliminated, and heterogeneity of the studies with all-type GC (I2 = 54.5%, P = 0.111) (Figure 2) was decreased.

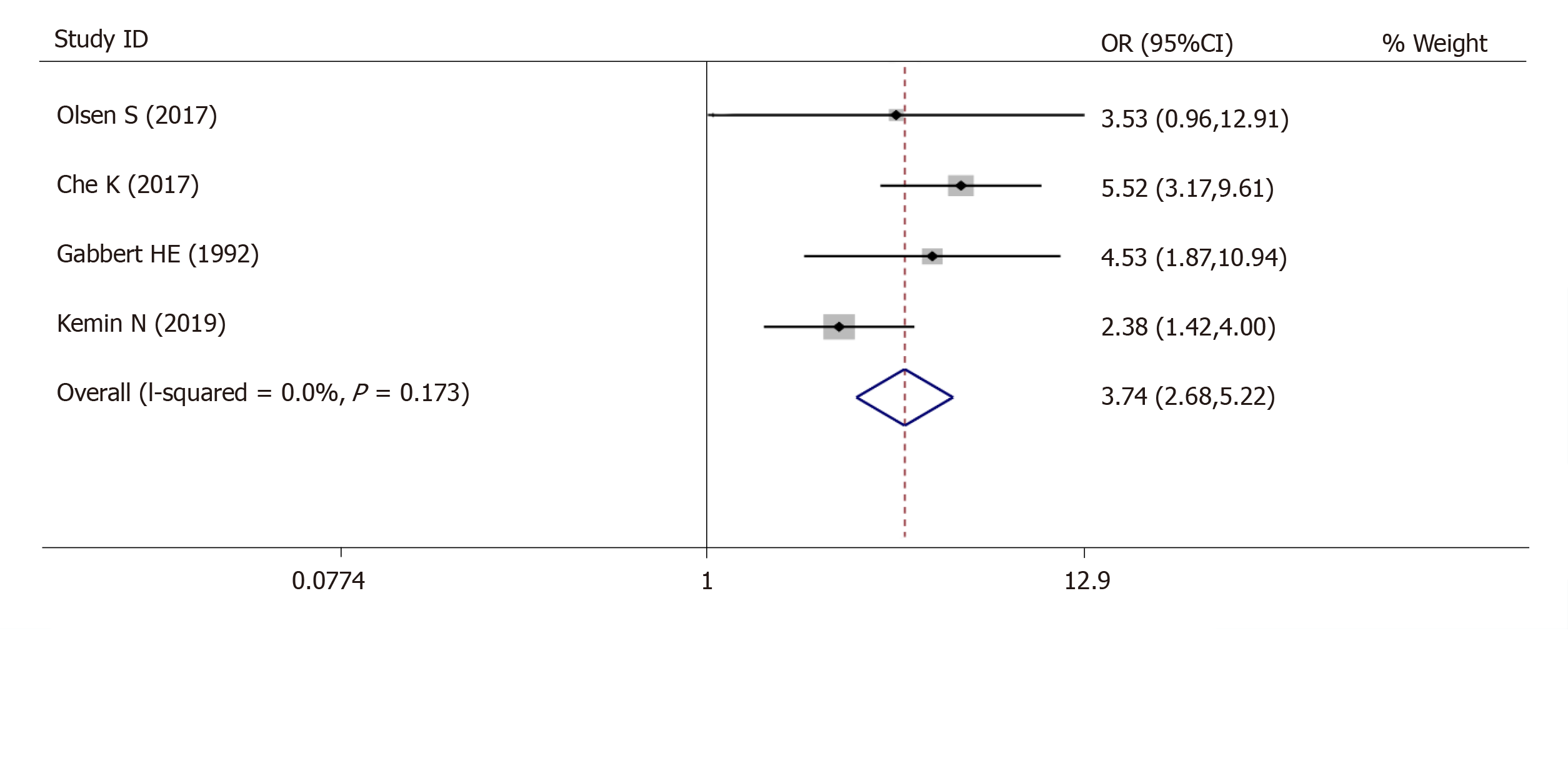

For tumor differentiation, 4 studies (980 patients) were qualified for the meta-analysis and there was statistically significant association between high-grade tumor budding and undifferentiated tumor status (OR = 3.74, 95%CI: 2.68-5.22, P < 0.01) (Figure 3). The test for heterogeneity was not significant using the fixed-effects model (Ι² = 39.8%, Ρ =0.173) (Figure 3).

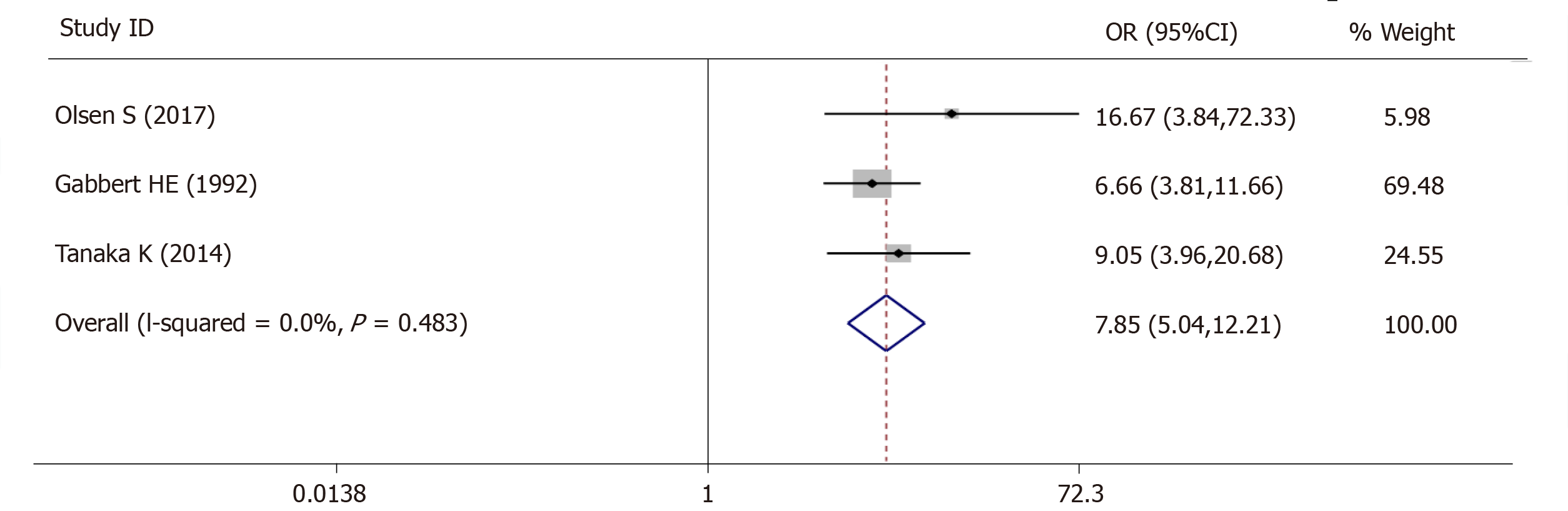

For lymph vascular invasion, 3 studies (545 patients) were qualified for the meta-analysis and there was statistically significant association between high-grade tumor budding and lymph vascular invasion (OR = 7.85, 95%CI: 5.04-12.21, P < 0.01) (Figure 4). The test for heterogeneity was not significant using the fixed-effects model (Ι² = 0%, Ρ = 0.483) (Figure 4).

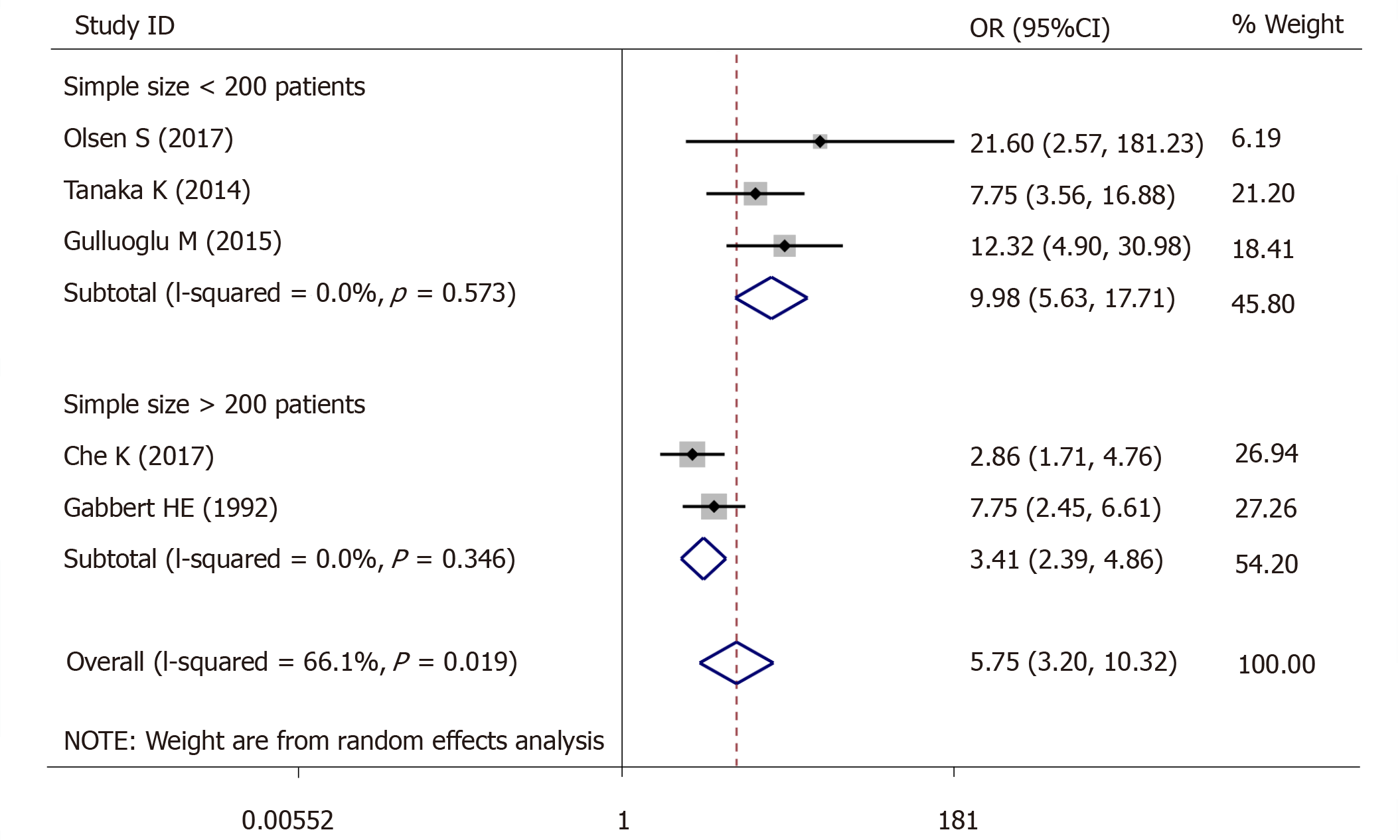

For lymph node metastasis, 5 studies (966 patients) were qualified for the meta-analysis and there was statistically significant association between high-grade tumor budding and lymph node metastasis (OR = 5.75, 95%CI: 3.20-10.32, P < 0.01) (Figure 5). The test for heterogeneity was significant using random-effects model (Ι² = 66.1%, Ρ = 0.019) (Figure 5). Furthermore, when the subgroups were stratified by patient number, the heterogeneity of the studies with > 200 patients (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.573) (Figure 5) and the studies with < 200 patients (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.346) (Figure 5) was totally eliminated.

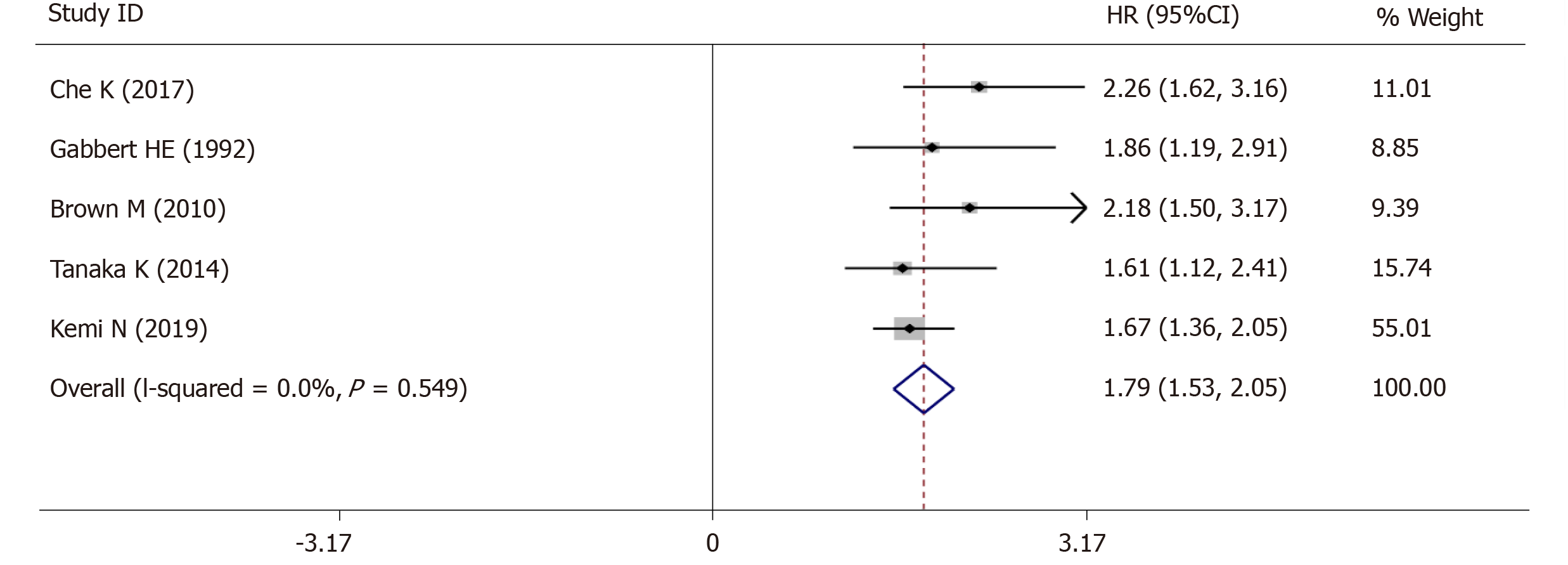

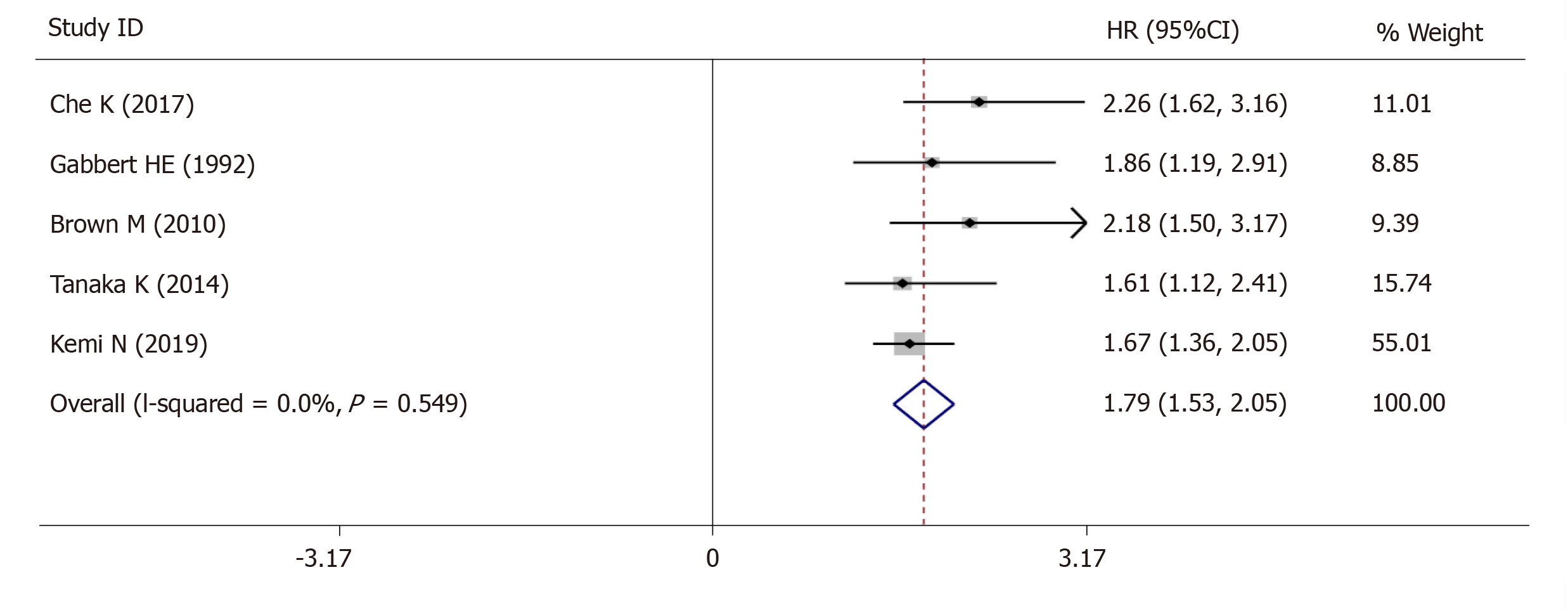

The 5-year OS was extracted from 5 studies (1833 patients) and analysis of the synthesized data with the fixed-effects model (I2 = 0.0%, Ρ =0.549) (Figure 6) revealed that high-grade tumor budding was associated with a poor 5-year OS (HR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.53-2.05, P < 0.01) (Figure 6). Subsequently, 2 studies (572 patients) on intestinal-type GC also revealed that high-grade tumor budding was associated with an adverse 5-year OS (HR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.45-2.42, P < 0.01) (Figure 7) and no significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0.0%, Ρ = 0.929) (Figure 7).

Tumor invasion - metastasis is a complex process that allows cancer cells to escape the major mass of the primary tumor and settle in distant organs or tissues[22]. Loss of cell cohesion is a crucial step in the process of cancer invasion, and metastasis is regarded as the most fatal event during cancer progression[23]. From a pathological point of view, tumor budding is a phenomenon encountered in various cancers in which a primary tumor sends a number of finger-like projections to adjacent stroma, some of which eventually detach from the main tumor mass as small cell clusters. It is generally accepted that tumor budding is the histological basis for invasion and metastasis[24].

Our meta-analysis integrated the data from 7 eligible studies involving 2178 patients with GC, and evaluated the role of tumor budding in GC, for the first time. Clinicopathological parameter analysis showed that high-grade tumor budding was correlated with an adverse grade of tumor differentiation, tumor invasion, lymph vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis. In addition, high-grade tumor budding was a statistically significant predictor of poor OS in patients with GC. We also observed the same results in intestinal-type GC, demonstrating that tumor budding may also have a prognostic role in intestinal-type GC. These factors are traditionally unfavorable predictors in patients with GC.

The combination of different types of GC was a disadvantage in the studies that evaluated tumor budding in GC. Niko Kemi indicated that there was no statistically significant relationship between tumor budding and OS in diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma[15]. Therefore, assessment of tumor budding in diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma is not recommended. Our study demonstrated that tumor budding was closely related to OS and tumor stage in patients with intestinal-type GC. Compared to other cancers, intestinal-type GC has a histopathological morphology similar to colorectal cancer[25]. In colorectal cancer, tumor budding has been proved to be an independent prognostic factor and has been included in European and Japanese guidelines[8,9]. A detailed investigation of the relationship between tumor budding and intestinal-type GC is required. The relationship between different types (Lauren classification) of GC and tumor budding may be different. The current study did not include a clear classification of GC, and this may have contributed to inaccurate results. In the future, separate analyses should be conducted on the relationship between tumor budding and different types of (Lauren classification) GC in order to better evaluate the impact of tumor budding on the prognosis of GC.

Tumor budding is considered to be the first step in cancer metastasis, as budding cells are thought to migrate through the extracellular matrix, invade lymph vascular structures and form metastatic tumor colonies in lymph nodes and at distant sites[26], and our results proved this point of view. The initiation of tumor budding is based on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process[26]. The relationship between tumor budding and EMT has been studied in many cancers, including colorectal cancer[27], esophageal cancer[28], pancreatic cancer[29,30], tongue squamous cell carcinoma[31], head and neck cancer[32], lung cancer[33], and breast cancer[12]. However, most EMT processes in tumor budding are incomplete, which suggests that tumor budding undergoes partial EMT. Thus, tumor budding has been proposed to be “EMT-like”[24]. In 2014, Tanaka et al[18] showed that higher TrkB expression in tumor budding was observed at the tumor invasive front. TrkB is closely related to EMT and was demonstrated in colon cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma[34,35], which promoted the EMT process and induced chemotherapy resistance. In the future, in-depth research should be conducted on this aspect, in order to determine the relationship between tumor budding and EMT, and the molecular mechanism underlying this relationship.

In this meta-analysis, no heterogeneity was observed, except in the studies on tumor budding associated with lymph node metastasis and tumor stage. To identify the source of heterogeneity of the association between tumor budding and tumor stage, we found that the included patients were all diagnosed with intestinal-type GC, whereas other authors chose to include patients with all types of GC. There was no significant heterogeneity in the correlation between tumor budding and tumor stage when the patients were divided into two groups (group 1: intestinal-type GC, group 2: all-types of GC). The study by Tanaka et al[18] was excluded from group 2, and no significant heterogeneity was observed in group 2. The study by Tanaka et al[18] did not include undifferentiated tumor samples, which may have contributed to the significant heterogeneity observed. Small sample size may also have contributed to the heterogeneity observed in the correlation between tumor budding and lymph node metastasis, as no significant heterogeneity was found when the number of patients was extended to 200.

Our meta-analysis has a few limitations. First, although the patients were divided into those with high-grade tumor budding and those with low-grade tumor budding, the stratification may change depending on the cut-off values, as the cut-off values for tumor budding varied across the included studies due to differences in the study populations and experimental methods. Second, some HRs and their corresponding 95%CIs were extracted from the survival curves. However, these data might be less reliable than those directly obtained from survival data. Third, a potential language bias exists in this meta-analysis, as non-English publications were excluded. Finally, publication bias was not tested due to the small number of included studies in the evaluation of tumor budding and prognosis of GC, which may have induced potential bias.

In conclusion, studies included in this meta-analysis came from seven countries and had large sample sizes. The results of this study showed that high-grade tumor budding was related to a poor 5-year OS and aggressive clinicopathological features in patients with GC. Tumor budding may be a unique predictive marker and the method used to detect tumor budding is simple, reproducible and inexpensive. Furthermore, we strongly advocate further studies on larger preoperative GC biopsies and different types of GC to confirm these results.

Our results demonstrated that high-grade tumor budding was related to poor 5-year overall survival (OS) in patients with gastric cancer (GC). Tumor budding may be a new prognostic indicator in GC.

This meta-analysis was carried out to clarify the prognostic and pathological impact of tumor budding in patients with GC.

The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library databases were searched. The data were extracted, and statistical analysis was conducted using STATA 15.0 software to assess the clinicopathological features and OS related to tumor budding in patients with GC. The odds ratios (ORs) were presented for dichotomous variables with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the HR was presented for time-to-event variables with 95%CIs.

Our meta-analysis suggested that high-grade tumor budding was significantly associated with tumor stage (OR = 6.63, 95%CI: 4.01-10.98, P < 0.01), undifferentiated tumor status (OR = 3.74, 95%CI: 2.68-5.22, P < 0.01), lymphovascular invasion (OR = 7.85, 95%CI: 5.04-12.21, P < 0.01), and lymph node metastasis (OR = 5.75, 95%CI: 3.20-10.32, P < 0.01). Moreover, high-grade budding predicted poor 5-year OS (HR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.53-2.05, P < 0.01) in patients with GC and poor 5-year OS (HR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.45-2.42, P < 0.01) in patients with intestinal-type GC.

This research is the first to demonstrate that high-grade tumor budding is related to poor 5-year OS and aggressive clinicopathological features in patients with GC.

In this meta-analysis, the close relationship between poor prognosis in GC and tumor budding was demonstrated, and it was found that intestinal-type GC is more closely related to tumor budding, and related research on diffuse GC is lacking. In the future, we will study the relationship between diffuse GC and tumor budding using our own sample library, and determine the underlying mechanism of the relationship between tumor budding and poor prognosis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chivu-Economescu M, de Melo FF S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55814] [Article Influence: 7973.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ, Estève J, Ogunbiyi OJ, Azevedo E Silva G, Chen WQ, Eser S, Engholm G, Stiller CA, Monnereau A, Woods RR, Visser O, Lim GH, Aitken J, Weir HK, Coleman MP; CONCORD Working Group. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2711] [Cited by in RCA: 3418] [Article Influence: 488.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edition. Wiley Blackwell: John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2017; . |

| 4. | In H, Solsky I, Palis B, Langdon-Embry M, Ajani J, Sano T. Validation of the 8th Edition of the AJCC TNM Staging System for Gastric Cancer using the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3683-3691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Morodomi T, Isomoto H, Shirouzu K, Kakegawa K, Irie K, Morimatsu M. An index for estimating the probability of lymph node metastasis in rectal cancers. Lymph node metastasis and the histopathology of actively invasive regions of cancer. Cancer. 1989;63:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hase K, Shatney C, Johnson D, Trollope M, Vierra M. Prognostic value of tumor "budding" in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:627-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ueno H, Murphy J, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC. Tumour 'budding' as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2002;40:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vieth M, Quirke P, Lambert R, von Karsa L, Risio M; International Agency for Research on Cancer. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Annotations of colorectal lesions. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 3:SE131-SE139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hyodo I, Igarashi M, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, Kanemitsu Y, Kokudo N, Muro K, Ochiai A, Oguchi M, Ohkura Y, Saito Y, Sakai Y, Ueno H, Yoshino T, Fujimori T, Koinuma N, Morita T, Nishimura G, Sakata Y, Takahashi K, Takiuchi H, Tsuruta O, Yamaguchi T, Yoshida M, Yamaguchi N, Kotake K, Sugihara K; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:1-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 597] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Karamitopoulou E, Gloor B. Tumour budding is a strong and independent prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Reply to comment. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2458-2459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koike M, Kodera Y, Itoh Y, Nakayama G, Fujiwara M, Hamajima N, Nakao A. Multivariate analysis of the pathologic features of esophageal squamous cell cancer: tumor budding is a significant independent prognostic factor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1977-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liang F, Cao W, Wang Y, Li L, Zhang G, Wang Z. The prognostic value of tumor budding in invasive breast cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:269-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Masuda R, Kijima H, Imamura N, Aruga N, Nakamura Y, Masuda D, Takeichi H, Kato N, Nakagawa T, Tanaka M, Inokuchi S, Iwazaki M. Tumor budding is a significant indicator of a poor prognosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma patients. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:937-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gabbert HE, Meier S, Gerharz CD, Hommel G. Tumor-cell dissociation at the invasion front: a new prognostic parameter in gastric cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 1992;50:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kemi N, Eskuri M, Ikäläinen J, Karttunen TJ, Kauppila JH. Tumor Budding and Prognosis in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:229-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brown M, Sillah K, Griffiths EA, Swindell R, West CM, Page RD, Welch IM, Pritchard SA. Tumour budding and a low host inflammatory response are associated with a poor prognosis in oesophageal and gastro-oesophageal junction cancers. Histopathology. 2010;56:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tanaka K, Shimura T, Kitajima T, Kondo S, Ide S, Okugawa Y, Saigusa S, Toiyama Y, Inoue Y, Araki T, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Tropomyosin-related receptor kinase B at the invasive front and tumour cell dedifferentiation in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2923-2934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gulluoglu M, Yegen G, Ozluk Y, Keskin M, Dogan S, Gundogdu G, Onder S, Balik E. Tumor Budding Is Independently Predictive for Lymph Node Involvement in Early Gastric Cancer. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Che K, Zhao Y, Qu X, Pang Z, Ni Y, Zhang T, Du J, Shen H. Prognostic significance of tumor budding and single cell invasion in gastric adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1039-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Olsen S, Jin L, Fields RC, Yan Y, Nalbantoglu I. Tumor budding in intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma is associated with nodal metastasis and recurrence. Hum Pathol. 2017;68:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Shimoda M, Mellody KT, Orimo A. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts are a rate-limiting determinant for tumour progression. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:19-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Christiansen JJ, Rajasekaran AK. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8319-8326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Grigore AD, Jolly MK, Jia D, Farach-Carson MC, Levine H. Tumor Budding: The Name is EMT. Partial EMT. J Clin Med. 2016;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4011] [Cited by in RCA: 4322] [Article Influence: 149.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, Nordlinger B, van de Velde CJ, Balmana J, Regula J, Nagtegaal ID, Beets-Tan RG, Arnold D, Ciardiello F, Hoff P, Kerr D, Köhne CH, Labianca R, Price T, Scheithauer W, Sobrero A, Tabernero J, Aderka D, Barroso S, Bodoky G, Douillard JY, El Ghazaly H, Gallardo J, Garin A, Glynne-Jones R, Jordan K, Meshcheryakov A, Papamichail D, Pfeiffer P, Souglakos I, Turhal S, Cervantes A. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2479-2516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1035] [Cited by in RCA: 1107] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Lugli A, Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I. Tumour budding: a promising parameter in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1713-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Niwa Y, Yamada S, Koike M, Kanda M, Fujii T, Nakayama G, Sugimoto H, Nomoto S, Fujiwara M, Kodera Y. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition correlates with tumor budding and predicts prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:764-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Hibi T, Aiura K, Kitagawa Y, Sakamoto M. Solitary cell infiltration is a novel indicator of poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1061-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kohler I, Bronsert P, Timme S, Werner M, Brabletz T, Hopt UT, Schilling O, Bausch D, Keck T, Wellner UF. Detailed analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor budding identifies predictors of long-term survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30 Suppl 1:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang C, Huang H, Huang Z, Wang A, Chen X, Huang L, Zhou X, Liu X. Tumor budding correlates with poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:545-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Almangush A, Salo T, Hagström J, Leivo I. Tumour budding in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma - a systematic review. Histopathology. 2014;65:587-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yamaguchi Y, Ishii G, Kojima M, Yoh K, Otsuka H, Otaki Y, Aokage K, Yanagi S, Nagai K, Nishiwaki Y, Ochiai A. Histopathologic features of the tumor budding in adenocarcinoma of the lung: tumor budding as an index to predict the potential aggressiveness. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1361-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kupferman ME, Jiffar T, El-Naggar A, Yilmaz T, Zhou G, Xie T, Feng L, Wang J, Holsinger FC, Yu D, Myers JN. TrkB induces EMT and has a key role in invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:2047-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fujikawa H, Tanaka K, Toiyama Y, Saigusa S, Inoue Y, Uchida K, Kusunoki M. High TrkB expression levels are associated with poor prognosis and EMT induction in colorectal cancer cells. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:775-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |