Published online Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.877

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: June 3, 2019

Revised: July 23, 2019

Accepted: August 20, 2019

Article in press: August 21, 2019

Published online: October 15, 2019

Processing time: 194 Days and 19.2 Hours

As a prognostic factor for colorectal cancer, lymph node (LN) status, particularly the number of LN harvested, has been demonstrated to be essential in the evaluation of quality control in terms of surgical specimen. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation, however, decreases the LN harvest. Therefore, certain approaches (such as fat clearance or methylene blue) has drawn significant attention in order to raise LN yield.

To compare the long-term oncologic outcome of ypN0 rectal cancer identified using fat clearance (FC) or conventional fixation (CF) following 30 Gy in 10 fractions (30 Gy/10f) of neoadjuvant radiotherapy (nRT).

Three hundred and eighty-two patients with resectable and locally advanced rectal cancer were treated by 30 Gy/10f intermediate nRT (biologically equivalent dose of 36 Gy) plus total mesorectal excision. Two specimen fixation methods (FC or CF) were non-randomly used. The ypN0 status was identified in 124 and 101 patients in the FL and CF groups, respectively. Primary endpoints were local recurrence-free survival (LRFS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

The median follow-up of patients was 5.1 years. The median numbers of retrieved LNs in the FC and CF groups were 19.5 (range, 4-47) and 12 (range, 0-44), respectively, with a significant difference (P = 0.000). The percentages of patients with 12 or more retrieved nodes were 82.3% and 50.5% (101/159) in the FC and CF groups, respectively, with a significant difference (P = 0.000). The LRFS at 5 years were 95.7% and 94.6% in the FC and CF groups, respectively, without statistical difference (P = 0.819). The CSS at 5 years were 92.0% and 87.2% in the FC and CF groups, respectively, without statistical difference (P = 0.482).

For patients with ypN0 rectal cancer who underwent 30 Gy/10f preoperative radiotherapy, the increased retrieval of LNs using fat clearance is not associated with survival benefit. This time-consuming fixation method has a low efficacy as a routine practice.

Core tip: Enhanced lymph node (LN) yield has been noticed to be associated with increasing accuracy in tumor staging and putative prognosis. By the means of fat-clearance technique, the LN retrieval was significantly higher in the fat-clearance group, compared with convention fixation. In terms of survival, however, for patients with negative LN, increased LN harvest was not associated with prolonged survival.

- Citation: Chen N, Sun TT, Li ZW, Yao YF, Wang L, Wu AW. Fat clearance and conventional fixation identified ypN0 rectal cancers following intermediate neoadjuvant radiotherapy have similar long-term outcomes. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(10): 877-886

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i10/877.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.877

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy (nRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) has significantly improved the local control of patients with rectal cancer, and it has become the standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancers[1,2]. Short-course nRT, compared with long-course chemoradiotherapy, has been demonstrated with the advantages of safety, high efficiency, good compliance, and improved oncological outcomes[3,4]. In two randomized trials[5], the short-course nRT is shown to be comparable with long-course chemoradiation for either local control or survival. In 2016, we reported the local control and survival data of intermediate nRT (30 Gy in 10 fractions; 30 Gy/10f) plus TME[6].

As the most important determinant of local recurrence and overall survival, lymph node (LN) status is critical in patients with rectal cancer. Inadequate LN staging may result in excessive or insufficient treatment. Several guidelines recommend a minimum examination of 12 LNs with the goal of accurately identifying the status of pN0 for colorectal cancers. However, this ‘12 LN’ threshold for precise histological examination of rectal cancer remains unclear, especially for patients undergoing neoadjuvant radiotherapy[1].

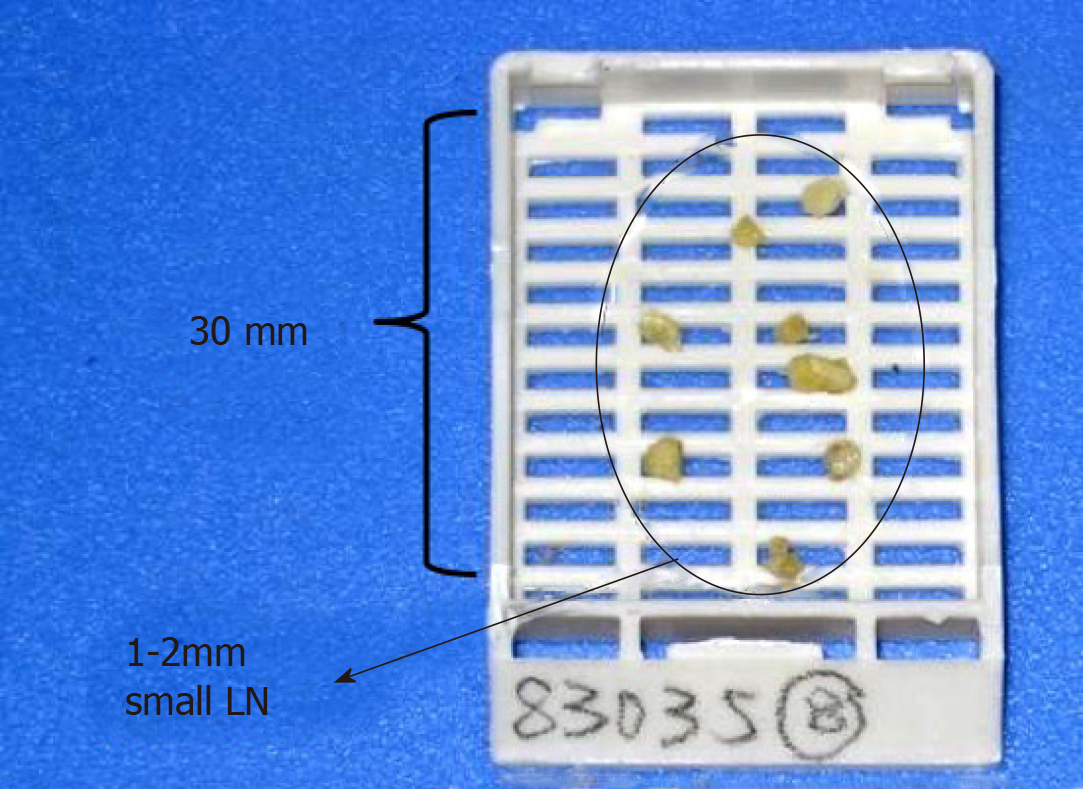

We previously reported the LN distribution and pattern of metastases in the mesorectum using the modified fat clearing technique. This technique can reveal small LNs (1-3 mm) and increase the LN harvest in the specimens of rectal cancers following 30 Gy/10f nRT. In the present study, we aimed to compare the long-term oncologic outcome of ypN0 rectal cancer identified using the modified fat clearance or conventional fixation method following 30 Gy/10f nRT.

Data were collected from patients who underwent intermediate nRT followed by TME surgery at Peking University Cancer Hospital from August 2002 to March 2011. In this study, the nRT regimen used was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Cancer Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before treatment.

Each patient enrolled in the study conformed to the following criteria: (1) The patient was diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma by biopsy; (2) The lesion was located within 10 cm from the anal verge; (3) The cancer was staged as T3-4 or any T and N+ by pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT); (4) Patients with distant metastases were excluded by imaging examinations; (5) The patient underwent neoadjuvant RT of 30 Gy/10f; (6) The patient underwent the surgery with the intent to cure, according to the TME principle; and (7) The patient was diagnosed with ypN0 following postoperative pathological evaluation.

Patients with the following characteristics were excluded: (1) The patient had undergone previous chemotherapy or pelvic radiation; (2) The patient had a malignant tumor history within 5 years; (3) Inflammatory bowel disease; (4) The presence of acute obstructive symptoms or serious comorbidities deemed not suitable for neoadjuvant radiation; and (5) The presence of unresectable cancer.

All patients enrolled underwent nRT followed by curative TME. The radiotherapy regimen included 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions for 2 wk. The biological equivalent dose (BED) of this regimen is 36 Gy. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) was routinely employed. Patients underwent radical curative surgery according to the principles of TME at a median interval of 2 wk (range: 2 to 8 wk) from the completion of nRT. After surgery, the patients underwent 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy if they were able to tolerate the therapy. Capecitabine alone, mFOLFOX6, or CapeOX was equivalently preferred regimen, as recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

The rectum specimen was fixed with modified LN revealing solution (LNRS) in order to facilitate LN yielding. The LNRS was prepared according to a modified Koren solution with a mixture of 40% ethanol, 40% ether, 10% acetic acid, and 10% formaldehyde. The entire rectal specimen was submerged in LNRS for 48 h. After fat clearance, the LNs appeared as chalk white foci against a yellow and translucent adipose background[7]. Tumor sliced samples and retrieved LNs were submitted for routine paraffin embedding and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Small LNs with a diameter of 1-3 mm could be clearly revealed through fat clearance (Figures 1 and 2).

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM system was employed for staging. Postoperatively, the results of the histopathologic examination of the specimens were reviewed by the same group of experienced pathologists, and circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement was assessed using the protocol of Kitz et al[8]. The negative status of N staging was identified through a routine microscopic evaluation. More intense histologic or immunohistochemical investigations (such as cytokeratin staining) to detect the presence of metastatic carcinoma were not employed in the present study.

The primary endpoints were local recurrence-free survival (LRFS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). The LRFS was defined as the time from the date of nRT completion to the date of local recurrence. The CSS was defined as the time from the date of nRT completion to the death from the same cancer or from other related causes. The secondary endpoints included the median number of retrieved LNs and the proportion of patients who achieved the 12 LN thresholds.

Patients were routinely followed at three-month intervals in the first two years after surgery and then at six-month intervals for the next three years. Evaluations included physical examination, serum CEA levels, complete blood count, blood chemical analysis, proctoscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal and pelvic CT, and chest radiography.

The IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 22.0 (Armonk, NY, IBM Corp.) was used for analyses. The enumeration variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. The categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to estimate the proportion of patients surviving or remaining disease-free at each time interval. The log-rank test was used for comparison of the Kaplan–Meier curves. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

In the corresponding time period, 382 patients with rectal cancer underwent 30 Gy/10f nRT plus TME at our center, and 212 patients underwent fat clearance. A total of 225 consecutive patients with ypN0 stage were analyzed, including 101 of 170 (59.1%) patients who had conventional fixation (CF group) and 124 of 212 (58.5%) patients who had fat clearance (FC group). The median patient age was 62 years (range, 28-83 years) and 58 years (range, 32-84 years) in the CF and FC groups, respectively. The percentages of male patients in the CF and FC groups were 63.4% and 55.6%, respectively. The baseline clinicopathological factors, including clinical T and N stages, tumor distance to anal verge, prestaging methods, resection types, ypT stage distribution, and CRM status, were well matched and comparable between the two groups. The percentage of patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy at our center was 30.7% (n = 69), and additional data were unavailable for other patients who received postoperative care in peripheral hospitals. Moreover, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy was not analyzed in this study. All patient characteristics, pre-staging methods, and pathological findings are listed in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Conventionalfixation (n = 101) | Fat clearance (n = 124) | P value |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 64 (63.4) | 69 (55.6) | 0.241 |

| Female | 37 (36.6) | 55 (44.4) | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Median | 62 | 58 | 0.496 |

| Range | 28-83 | 32-84 | |

| cT stage | |||

| T0-2 | 4 (4.0) | 9 (7.3) | 0.170 |

| T3 | 93 (92.1) | 114 (91.9) | |

| T4a | 4 (4.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| cN stage | |||

| N0 | 26 (25.7) | 30 (24.2) | 0.789 |

| N+ | 75 (74.3) | 94 (75.8) | |

| Distance from anal verge (cm) | |||

| Median | 5 | 5 | 0.299 |

| Range | 2-10 | 1-9 | |

| Pre-treatment staging | |||

| MRI + ERUS | 27 (26.7) | 22 (17.7) | 0.428 |

| MRI | 15 (14.9) | 23 (18.5) | |

| CT + ERUS | 15 (14.9) | 19 (15.3) | |

| ERUS | 30 (29.7) | 35 (28.2) | |

| CT | 14 (13.9) | 25 (20.2) | |

| Interval from RT to surgery | |||

| Median | 2 | 2 | 0.702 |

| Range | 1-8 | 1-6 | |

| Type of resection | |||

| Non-APR | 68 (67.3) | 90 (72.6) | 0.391 |

| APR | 33 (32.7) | 34 (27.4) | |

| ypT stage | |||

| ypCR | 7 (6.9) | 14 (11.3) | 0.550 |

| T1 | 8 (7.9) | 11 (8.9) | |

| T2 | 37 (36.6) | 51 (41.1) | |

| T3 | 47 (46.5) | 47 (37.9) | |

| T4a | 2 (2.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| CRM status | |||

| Positive | 6 (5.9) | 8 (6.5) | 0.875 |

| Negative | 95 (94.1) | 116 (93.5) | |

The median number of retrieved LNs in the FC group was significantly higher than that in the CF group (19.5 and 12, P = 0.000), which is similar to the difference found in the ypT0-2 stages (19 and 9, P = 0.000) and ypT3-4 stages (21.5 and 13, P = 0.000).

The proportions of patients who achieved the 12 LN threshold were 82.3% and 50.5% in the FC and CF groups, respectively, with a statistical difference (P = 0.000), which is similar to the difference found in ypT0-2 stages (81.6% and 34.6%, P = 0.000). The proportion of patients who achieved the 12 LN threshold was not statistically different in ypT3-4 stages between the FC and CF groups (83.3% and 67.3%, P = 0.068).

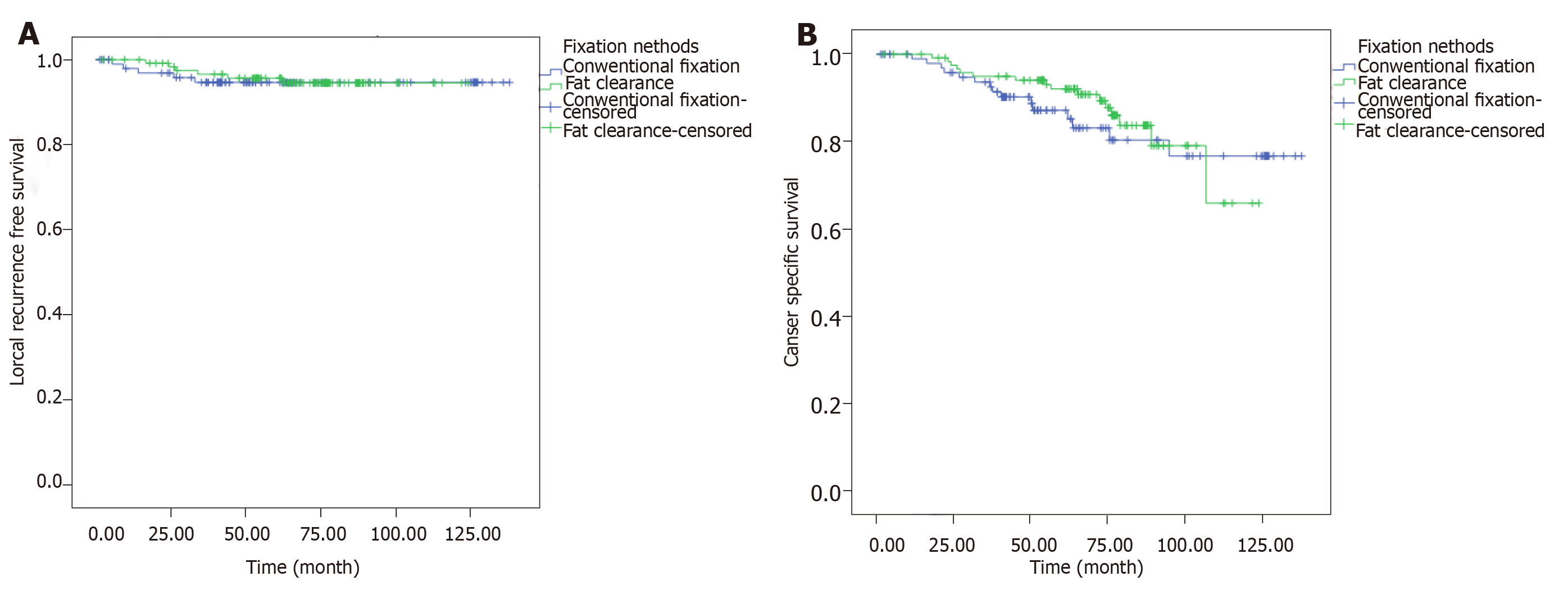

Last follow-up was implemented in December 2014. The median follow-up period was 5.1 years. The estimated 5-year LRFS were 95.7% and 94.6% in the FC and CF groups, respectively, without significant difference (P = 0.819) (Figure 3; Table 2). The CSS at 5 years were 92.0% and 87.2% in the FC and CF groups, respectively, without statistical difference (P = 0.482) (Figure 3B).

| Characteristic | Fat clearance | Conventionalfixation | P value |

| LNs retrieved [median (range)] | |||

| All T stages | 19.5 (4-57) | 12 (0-44) | 0.000 |

| ypT0-2 | 19 (5-57) | 9 (0-30) | 0.000 |

| ypT3-4 | 21.5 (4-55) | 13 (1-44) | 0.000 |

| Lymph nodes ≥ 12 | |||

| All T stages | 82.3% | 50.5% | 0.000 |

| ypT0-2 | 81.6% | 34.6% | 0.000 |

| ypT3-4 | 83.3% | 67.3% | 0.068 |

| 5 yr-LRFS rate | 95.7% | 94.6% | 0.819 |

| 5 yr-CSS rate | 92.0% | 87.2% | 0.482 |

The ideal threshold for retrieved LNs in patients with rectal cancer has been unclear for years, and the 12 LN threshold is extrapolated from the recommendation of pathological identification for stage II colon cancer. For patients with rectal cancer who underwent nRT, the retrieved LN number significantly decreases from 7% to 53% compared to those who did not undergo nRT[9,10]. After nRT, the proportion of patients who achieved more than 12 LNs is also low, from 31% to 37%[11].

Short-course nRT is recommended as routine care for low- or moderate-risk patients with rectal cancer according to the NCCN and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines[12,13]. Moreover, short-course nRT decreases local failure than long-course postoperative chemoradiotherapy[3]. We previously reported the survival data of patients who underwent intermediate nRT plus TME for locally advanced rectal cancer, which has a similar biological equivalent dose (BED) and treatment schedule to short-course nRT[14]. We previously used the fat clearance as an intensive LN revealing method to reduce the difficulty of finding small LNs in the mesorectal fat tissue and to harvest more LNs.

In the present study, we focused on testing the effect of fat clearance to identify the true ypN0 rectal cancer and to observe whether the fat clearance-confirmed ypN0 rectal cancer could have survival benefit than those diagnosed using conventional fixation. Initially, we hypothesized that the ypN0 cases identified by fat clearance could eliminate those under-staged cases with small metastatic LNs. From the data of this study, the fat clearance could significantly increase the retrieval of LNs for ypN0 rectal cancer following 30 Gy/10f preoperative radiotherapy; however, the final comparison showed that the survival rates are similar between the FC and CF groups. The findings of our study demonstrated the fact that the increased LN retrieval is not associated with survival benefit in patients with ypN0 rectal cancer and might provide piece of evidence to question the necessity of pursuing higher number LN retrieval after nRT.

The ideal cut-off value of LN retrieval is highly controversial in colorectal surgery, especially for rectal cancer following nRT. In previous studies, the aim of retrieving more LNs is to discriminate positive LNs, since the positive ypN stage status is one of the most influential factors of long-term outcome[15,16]. Moreover, more retrieved LNs seem to be associated with better survival even in N0 or ypN0 patients[17]. Thus, a cut-off number of 3 or 7 or 8 or 11 LNs, or a range from 7-11 LNs based on survival stratification was recommended in various retrospective studies[18]. In the present study, the median LN retrieval number was 12 and 19.5 in the CF and FC groups, respectively, which is similar to other reports. However, data from other studies indicated that the number of retrieved LNs failed to be demonstrated as a prognostic factor for either overall or disease-free survival[19]. Furthermore, the absence of LNs (ypNx) in the resected rectum after nCRT seems to be associated with good disease-free survival rates and reflect improved response to nCRT rather than inappropriate or suboptimal radicality of resection. Finally, many studies using survival data to confirm the cut-off value of LN number conclude that the ypN status is a more stronger prognostic factor than LN retrieval itself[20,21].

Apart from the controversy over the cut-off value of LNs, more issues were raised in this field. First, the point that more LN counts could increase the N positive rate is challenged. The 12 LN threshold is not a universal standard among hospitals, and efforts to increase node examination rates have a limited value as a public health intervention[22]. Second, data from a large population of patients with colorectal cancer also demonstrated that the number of LNs for colorectal cancer experienced a markedly increase in the last two decades but was not associated with an overall shift to higher-staged tumors, leading to the controversy over the upstaging mechanism as the primary basis for improved survival in patients with more LNs evaluated[23]. In fact, Ervine et al[24] concluded that only 1% of colorectal cancers were upstaged using an enhancing method for LN examination. Finally, the complexity of the LN count should be considered, in terms of mesenteric LN anatomy, molecular aspects, tumor characteristics, surgical procedure, and utilization of different sampling techniques[25,26]. In the present study, the ypN0 rate was 60% in both the FC and CF groups of all rectal cancers after 30 Gy/10f nRT. These data consolidate the marginal utility of retrieving more small LNs and might support the hypothesis of the constant nodal positivity of 40% across a wide range of studies.

Compared with colon cancer, LN retrieval for rectal cancer is also influenced by the intensity and schedule of nRT/nCRT and patients’ intrinsic sensitivity to nRT. Therefore, several enhancing methods for LN examination, including various LN revealing solutions, meticulous sampling/resampling procedure or maneuver, and some staining methods such as methylene blue injection, were used in rectal cancer[27,28]. In this study, we used a modified Koren solution to reveal more small LNs. We obtained significantly more LNs than using the conventional fixation; nevertheless, this effort neither identified truer ypN0 rectal cancers nor achieved survival benefit in fat clearance-confirmed ypN0 patients. For this reason, we conclude that fat clearance is not feasible to be routinely used for rectal cancers following 30 Gy/10f nRT. We do not also advocate using this method for resampling in rectal cancers with ≤ 12 LNs, because fat clearance is time-consuming and with potential toxicity, and the ideal cut-off value of LN retrieval is still unclear.

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective nature and long time span of the present study limited its strength. Second, the unique nRT schedule in this study has lower BED and shortened interval than the conventional long-course nCRT, which limited the utilization of the finding in other series. Despite these limitations, the sample size and efforts of pathological management remain convincing when compared with the literature. Although the conclusion is a negative result, we believe that this article could add useful and referable information for study of LN retrieving after nRT in future.

In conclusion, for patients with ypN0 rectal cancer who underwent 30 Gy/10f preoperative radiotherapy, the practice of increased retrieval of LNs using fat clearance might not be an essential factor associated with survival benefit. The efficacy of this time-consuming fixation method remains controversial, compared with the conventional practice.

For accurate tumor staging, it is recommended to obtain at least 12 lymph nodes (LNs) by international guidelines (such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines). However, the number of LN decreases after neoadjuvant chemoradiation, leading to the hypothesis that enhanced LN yield would bring survival benefit.

Different methods have been implemented, trying to increase LN harvest. In this study, we employed the fat-clearance technique for LN yielding. So far, this study provided convincing evidence with big numbers of cases and long-term follow-up.

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of fat-clearance technique in terms of LN retrieval and potential prognostic values.

This study employed the fat-clearance technique, which was demonstrated to be effective with a high sensitivity.

The conclusion of this study confirms the fact that for patients without LN metastasis, higher yield of LN might be only a time-consuming procedure, rather than prognostic approach.

In rectal cancer patients undergoing neoadvjuant chemoradiation without LN metastasis, the pursuit for more LN harvest is not beneficial. Fat-clearance technique might not be useful for pN0 patients. Decreased number of LN in rectal cancer patients with neoadjuvant chemoradiation might be of nature, with no necessity to increase retrieval in pN0 patients. In pN0 rectal cancer patients with neoadjuvant conformal radiotherapy (CRT), additional LN retrieval might be useless. The 12 LN rule might not be essential for accurate staging. The fat-clearance technique utilized in this paper is a new method. The increased number of LNs did not bring in longer survival and was not associated with survival benefit. The pursuit for higher number of LNs retrieved might be of no use, therefore, to prolong patients’ survival, new strategy of treatment might be useful.

The 12 LN rule might not work in patients with neoadjuvant CRT. Lymph node positivity or positive LNs might be more important in terms of prognostic value. Methods for tracing the positive LN might be the best way for the research in the future.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Parakkal D, Raff E S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv22-iv40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1112] [Cited by in RCA: 1190] [Article Influence: 148.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Cederquist L, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Grem JL, Grothey A, Hochster HS, Hoffe S, Hunt S, Kamel A, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Mulcahy MF, Murphy JD, Nurkin S, Saltz L, Sharma S, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Wuthrick E, Gregory KM, Gurski L, Freedman-Cass DA. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:874-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 113.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abraha I, Aristei C, Palumbo I, Lupattelli M, Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, De Florio R, Valentini V. Preoperative radiotherapy and curative surgery for the management of localised rectal carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD002102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Kranenbarg EK, Putter H, Wiggers T, Rutten H, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, Leer JW, van de Velde CJ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:693-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 853] [Cited by in RCA: 871] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Raldow AC, Chen AB, Russell M, Lee PP, Hong TS, Ryan DP, Cusack JC, Wo JY. Cost-effectiveness of Short-Course Radiation Therapy vs Long-Course Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e192249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang L, Li YH, Cai Y, Zhan TC, Gu J. Intermediate Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy Combined With Total Mesorectal Excision for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Outcomes After a Median Follow-Up of 5 Years. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yao YF, Wang L, Liu YQ, Li JY, Gu J. Lymph node distribution and pattern of metastases in the mesorectum following total mesorectal excision using the modified fat clearing technique. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:1073-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kitz J, Fokas E, Beissbarth T, Ströbel P, Wittekind C, Hartmann A, Rüschoff J, Papadopoulos T, Rösler E, Ortloff-Kittredge P, Kania U, Schlitt H, Link KH, Bechstein W, Raab HR, Staib L, Germer CT, Liersch T, Sauer R, Rödel C, Ghadimi M, Hohenberger W; German Rectal Cancer Study Group. Association of Plane of Total Mesorectal Excision With Prognosis of Rectal Cancer: Secondary Analysis of the CAO/ARO/AIO-04 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e181607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang H, Safar B, Wexner S, Zhao R, Cruz-Correa M, Berho M. Lymph node harvest after proctectomy for invasive rectal adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant therapy: does the same standard apply? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:549-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miller ED, Robb BW, Cummings OW, Johnstone PA. The effects of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on lymph node sampling in rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1002-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mechera R, Schuster T, Rosenberg R, Speich B. Lymph node yield after rectal resection in patients treated with neoadjuvant radiation for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:84-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, Nordlinger B, van de Velde CJ, Balmana J, Regula J, Nagtegaal ID, Beets-Tan RG, Arnold D, Ciardiello F, Hoff P, Kerr D, Köhne CH, Labianca R, Price T, Scheithauer W, Sobrero A, Tabernero J, Aderka D, Barroso S, Bodoky G, Douillard JY, El Ghazaly H, Gallardo J, Garin A, Glynne-Jones R, Jordan K, Meshcheryakov A, Papamichail D, Pfeiffer P, Souglakos I, Turhal S, Cervantes A. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2479-2516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1035] [Cited by in RCA: 1105] [Article Influence: 85.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, Marijnen CA, Rödel C, Gambacorta MA, Boelens PG, Aristei C, van de Velde CJ. EURECCA consensus conference highlights about rectal cancer clinical management: the radiation oncologist's expert review. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang L, Gu J. Risk factors for symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection for rectal cancer with 30 Gy/10 f/2 w preoperative radiotherapy. World J Surg. 2010;34:1080-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | But-Hadzic J, Velenik V. Preoperative Intensity-modulated Chemoradiation Therapy with Simultaneous Integrated Boost in Rectal Cancer: 2-year Follow-up Results of Phase II Study. Radiol Oncol. 2018;52:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lu Z, Cheng P, Yang F, Zheng Z, Wang X. Long-term outcomes in patients with ypT0 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and curative resection. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:272-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, Greene FL, Stewart A. Revised tumor and node categorization for rectal cancer based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results and rectal pooled analysis outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:256-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hall MD, Schultheiss TE, Smith DD, Fakih MG, Kim J, Wong JY, Chen YJ. Impact of Total Lymph Node Count on Staging and Survival After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy for Rectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S580-S587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Persiani R, Biondi A, Gambacorta MA, Bertucci Zoccali M, Vecchio FM, Tufo A, Coco C, Valentini V, Doglietto GB, D'Ugo D. Prognostic implications of the lymph node count after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2014;101:133-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee CHA, Wilkins S, Oliva K, Staples MP, McMurrick PJ. Role of lymph node yield and lymph node ratio in predicting outcomes in non-metastatic colorectal cancer. BJS Open. 2018;3:95-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee WS, Lee SH, Baek JH, Lee WK, Lee JN, Kim NR, Park YH. What does absence of lymph node in resected specimen mean after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G, Smith MA. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results--Medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401-4409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Moro-Valdezate D, Pla-Martí V, Martín-Arévalo J, Belenguer-Rodrigo J, Aragó-Chofre P, Ruiz-Carmona MD, Checa-Ayet F. Factors related to lymph node harvest: does a recovery of more than 12 improve the outcome of colorectal cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ervine A, Houghton J, Park R. Should lymph nodes from colorectal cancer resection specimens be processed in their entirety? J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:114-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Denham LJ, Kerstetter JC, Herrmann PC. The complexity of the count: considerations regarding lymph node evaluation in colorectal carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:342-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jin M, Frankel WL. Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2018;27:401-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen L, Kalady MF, Goldblum J, Seyidova-Khoshknabi D, Burks EJ, Roberts PL, Ricciardi R. Does reevaluation of colorectal cancers with inadequate nodal yield lead to stage migration or the identification of metastatic lymph nodes? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chapman B, Paquette C, Tooke C, Schwartz M, Osler T, Weaver D, Wilcox R, Hyman N. Impact of Schwartz enhanced visualization solution on staging colorectal cancer and clinicopathological features associated with lymph node count. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1028-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |