Published online Oct 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.857

Peer-review started: February 27, 2019

First decision: April 11, 2019

Revised: May 1, 2019

Accepted: September 12, 2019

Article in press: September 12, 2019

Published online: October 15, 2019

Processing time: 231 Days and 15 Hours

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) followed by resection and postoperative multi-agent chemotherapy (maChT) is the standard of care for locally advanced rectal cancer. Using this approach, maChT administration can be delayed for several months, leading to concern for distant metastases. To counteract this, a novel treatment approach known as total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) has gained popularity, in which patients receive both maChT and nCRT prior to resection. We utilized the National Cancer Database to examine temporal trends in TNT usage, and any potential effect on survival.

To study the temporal trends in the usage of TNT and evaluate its efficacy compared to neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

We queried the National Cancer Database for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, Stage II-III, from 2004-2015 treated with nCRT or TNT. TNT was defined as maChT initiated ≥ 90 d prior to nCRT initiation. Overall survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of last contact or death using Kaplan-Meier curves to present the cumulative probability of survival, with log-rank statistics to assess significance. Multivariable cox regression was used to identify predictors of survival and propensity score analysis accounted for bias.

We identified 9066 eligible patients, with 8812 and 254 patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by maChT and TNT, respectively. Nodal involvement, stage III disease, and treatment in recent years were predictive of TNT use. There was greater use of TNT with more advanced stage, specifically > 1 node involved (odds ratio [OR] = 2.88, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.11-3.93, P < 0.01) and stage III disease (OR = 2.88, 95%CI: 2.11-3.93, P < 0.01). From 2010 to 2012 the use of TNT increased (OR = 2.41, 95%CI: 1.27-4.56, P < 0.01) with a greater increase from 2013 to 2015 (OR = 6.62, 95%CI: 3.57-12.25, P < 0.01). Both the TNT and neoadjuvant chemoradiation arms had a similar 5-year survival at 76% and 78% respectively. Multivariable analysis with propensity score demonstrated that increased age, high comorbidity score, higher grade, African American race, and female gender had worse overall survival.

Our data demonstrates a rising trend in TNT use, particularly in patients with worse disease. Patients treated with TNT and nCRT had similar survival. Randomized trials evaluating TNT are underway.

Core tip: Total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT) has been gaining favor as the treatment of choice for rectal carcinoma. It has been linked to better sphincter preservation and overall improved quality of life. Our study aim was to compare TNT with traditional chemotherapy and radiation over the last 10 years and evaluate the differences in outcomes. Our study confirms a rising trend in the of use of TNT especially in patients diagnosed with locally advanced rectal cancer. Patients treated with TNT had higher burden of disease but had similar survival outcomes as those treated with traditional chemotherapy and radiation.

- Citation: Babar L, Bakalov V, Abel S, Ashraf O, Finley GG, Raj MS, Lundeen K, Monga DK, Kirichenko AV, Wegner RE. Retrospective review of total neoadjuvant therapy. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(10): 857-865

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i10/857.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i10.857

Over the past several years, there have been several advances in the medical and surgical treatment of locally advanced, stage II and III rectal cancer. With the advent of total mesorectal excision as well as anal laparoscopic surgeries, treatment options continue to improve and result in lower rates of local disease recurrence in these patients. There has also been an ongoing paradigm shift in the approach to chemoradiation administration. The standard of care for rectal cancer is neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) followed by surgery and then postoperative multiagent chemotherapy based on several randomized trials[1,2]. A novel approach called total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT) has recently gained favor whereby patients are given both nCRT as well as multiagent chemotherapy prior to surgery. TNT use has been associated with better compliance, decrease in toxicities, and higher rates of anal sphincter preservation[3-9].

This change in approach has been based on increasing evidence that there is better quality of life with improved functionality, decreased toxicity, and lower rates of recurrence with preoperative treatment[4-9]. Patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy have delays in the administration of treatment secondary to long postoperative recovery time and inability to regain their prior functional status. Compliance is an issue in these patients, and they often do not receive their scheduled chemotherapy or it is delayed[3]. Additionally, with the use of TNT, carefully selected patients who have a clinical complete response can in some instances avoid surgery altogether and instead be followed with close observation (i.e. “watch and wait approach”)[10].

With local disease recurrence rates falling due to the use of total mesorectal excision, which is a close dissection of the rectum and para rectal lymph nodes within the mesorectal envelope[11], there is still an increased concern for distant metastases. Over 35% of patients treated with the standard therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) have distant recurrence of disease[12]. One reason for this is the presence of micrometastases. As surgery only addresses local disease and potentially delays the administration of chemotherapy, these micrometastases can result in distant metastasis. The administration of TNT helps tackle this problem by providing total systemic treatment prior to surgical resection. It also gives clinicians the ability to detect patients who do not respond to the treatment in a timely manner[13].

As such, we queried the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to analyze the trends in treatment approach towards locally advanced rectal carcinoma and to determine if there has been a rise in TNT use in recent years. Additionally, we identified the factors affecting the rate of utilization of TNT and how they correlate with patients from different socioeconomic strata.

The aim of this study was to use the NCDB to evaluate the trends in treatment options for LARC, specifically with regards to TNT utilization. The NCDB is a national database cataloguing approximately 70% of all cancer cases within the United States[14]. This information is collected from over 1500 cancer treatment centers. This database details information about patients’ demographics, disease, treatment, and mutations for several cancer subtypes. The data that are submitted to this database must meet established quality standards and is managed by the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. We used data extracted from a de-identified NCDB record. This study was exempt from review by the internal revenue board due to its deidentified and retrospective nature.

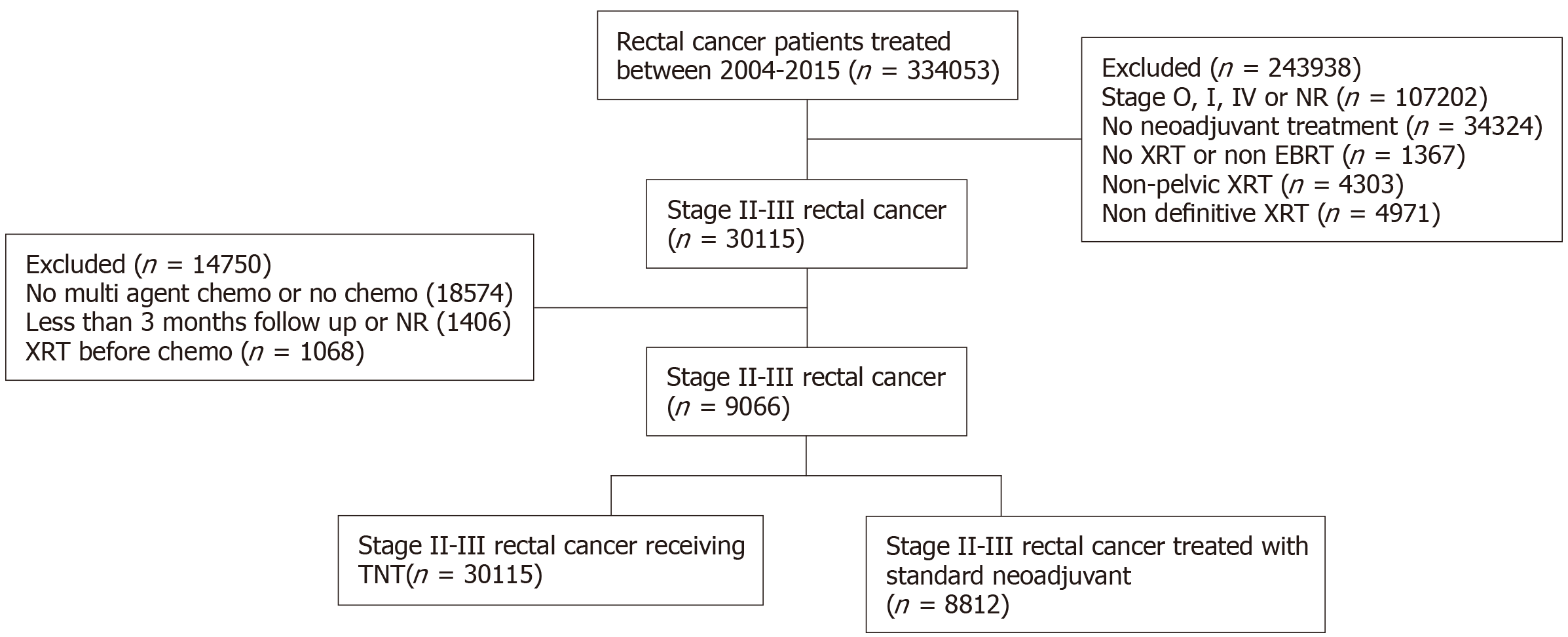

We queried the NCDB for patients diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 2004 and 2014. Patients with stage II and III cancer were included and the data were analyzed to extract if the treatment modality was TNT or multi-agent chemotherapy (maChT). TNT entails the administration of induction chemotherapy as well as chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery, while maChT is postoperative multiagent chemotherapy, which is given in the adjuvant setting and is the current standard of care, and is often combined with neoadjuvant chemoradiation preop[1]. All patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, leaving a total of 9066 patients (Figure 1). We analyzed the patient demographics, clinical course, treatment modalities, and survival outcome among our patient population. The patient characteristics used for analysis were age, gender, insurance status, income, facility location and type, tumor stage, treatment modality, and nodal stage.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated using the date of diagnosis and the last contact or death. This data were then analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative probability of survival. Log rank statistics were employed to assess for statistical significance between the two groups. Multivariate cox regression was used to identify factors associated with OS. The P value was set at < 0.005.

Multivariable cox regression was done for OS considering the treatment, stage, facility type, location, education status, age, gender, insurance type, race, comorbidity score, mean household income, age distribution, and year of diagnosis. The odds ratios (ORs) for the two groups, those who underwent TNT and those were treated with conventional neoadjuvant treatment, were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI) along with the corresponding type 1 error (P-value). To account for any potential biases within the two treatment arms, propensity score analysis was used.

Using the eligibility criteria defined above, our final study population consisted of 9066 patients [5648 men (62%), 3418 women (38%)]. These patients were separated on the basis of the treatment they received: 8812 patients received nCRT and 254 patients received TNT from 2004 to 2015. Of the cohort, 3694 patients had stage II disease and 5372 had stage III disease with 2525 patients having > 1 node positive (Figure 1). The majority of patients were less than age 65 and had private payer insurance. A summary of the clinical and demographics of our study population are in Table 1.

| Characteristic | TNT, n = 254 (%) | Conventional neoadjuvant treatment, n = 8812 (%) | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 151 (59) | 5497 (62) | 1 | Ref | |

| Female | 103 (41) | 3315 (38) | 1.13 | 0.88-1.46 | 0.34 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 205 (81) | 7757 (88) | 1 | Ref | |

| African American | 22 (8) | 624 (7) | 1.33 | 0.85-2.09 | 0.21 |

| Other | 27 (11) | 431 (5) | 2.37 | 1.57-3.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Comorbidity score | |||||

| 0 | 224 (88) | 7175 (81) | 1 | Ref | |

| 1 | 27 (11) | 1366 (16) | 0.63 | 0.42-0.95 | 0.026 |

| ≥ 2 | 3 (1) | 271 (3) | 0.35 | 0.11-1.11 | 0.08 |

| Insurance | |||||

| Not Insured | 9 (3) | 417 (5) | 1 | Ref | |

| Private Payer | 178 (70) | 5313 (60) | 1.55 | 0.79-3.05 | 0.20 |

| Government | 63 (25) | 2981 (34) | 0.98 | 0.48-1.98 | 0.95 |

| Unrecorded | 4 (2) | 101 (1) | 1.84 | 0.55-6.08 | 0.32 |

| Education % | |||||

| ≥ 29 | 39 (15) | 1262 (14) | 1 | Ref | |

| 20 to 28.9 | 53 (21) | 2231 (25) | 0.77 | 0.51-1.17 | 0.22 |

| 14 to 19.9 | 84 (33) | 2960 (34) | 0.92 | 0.62-1.35 | 0.66 |

| Locations | |||||

| Metro | 209 (82) | 6915 (78) | 1 | Ref | |

| Urban | 16 (6) | 1474 (17) | 0.36 | 0.22-0.60 | 0.0001 |

| Rural | 4 (2) | 207 (2) | 0.64 | 0.24-1.74 | 0.38 |

| Unrecorded | 25 (10) | 216 (2) | 3.83 | 2.48-5.92 | < 0.0001 |

| Income, United States dollars | |||||

| < 30000 | 25 (10) | 1391 (16) | 1 | Ref | |

| 30000 to 35000 | 37 (15) | 2086 (24) | 0.99 | 0.59-1.65 | 0.96 |

| 35000 to 45999 | 53 (20) | 2510 (29) | 1.17 | 0.73-1.90 | 0.51 |

| > 46000 | 139 (55) | 2773 (31) | 2.79 | 1.81-4.29 | < 0.0001 |

| Distance to treatment facility, miles | |||||

| ≤ 8.5 | 82 (32) | 3561 (41) | 1 | Ref | |

| > 8.5 | 172 (68) | 5205 (59) | 1.44 | 1.10-1.87 | 0.0079 |

| Age distribution in yr | |||||

| ≤ 65 | 208 (82) | 6734 (76) | 1 | Ref | |

| > 65 | 46 (18) | 2078 (24) | 0.72 | 0.52-0.99 | 0.04 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 2004-2006 | 11 (4) | 1125 (13) | 1 | Ref | |

| 2007-2009 | 19 (7) | 2256 (26) | 0.86 | 0.41-1.82 | 0.69 |

| 2010-2012 | 73 (29) | 3097 (35) | 2.41 | 1.27-4.56 | 0.0068 |

| 2013-2015 | 151 (59) | 2334 (26) | 6.62 | 3.57-12.25 | <0.0001 |

| Stage grouping | |||||

| 2 | 50 (20) | 3644 (41) | 1 | Ref | |

| 3 | 204 (80) | 5168 (59) | 2.88 | 2.11-3.93 | < 0.0001 |

| Nodes | |||||

| 0 | 170 (67) | 5277 (60) | 1 | Ref | |

| 1 | 25 (10) | 1089 (12) | 0.71 | 0.47-1.09 | 0.12 |

There was greater use of TNT with more advanced stage, specifically > 1 node involved (OR = 2.88, 95%CI: 2.11-3.93, P < 0.01) and stage III disease (OR = 2.88, 95%CI: 2.11-3.93, P < 0.01). From 2010 to 2012, the use of TNT increased (OR = 2.41, 95%CI: 1.27-4.56, P < 0.01) with a greater increase from 2013 to 2015 (OR = 6.62, 95%CI: 3.57-12.25, P < 0.01) (Table 1). The 5-year survival for both treatment arms was similar at 76% and 78%, respectively. Multivariable analysis found age > 58, higher income, urban location, academic treatment facility, and lower co-morbidity score as predictors for worse OS. Propensity score matching demonstrated increased age, higher comorbidity score, higher tumor grade, African American race, and gender as predictive of worse OS.

Colorectal cancer is the fourth highest occurring cancer in the United States and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths as per the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data[15]. Patients with locally advanced rectal carcinoma, which includes patients with T2 or T3 disease with or without nodal involvement, benefit from a multidisciplinary treatment approach. These patients are treated with multiagent chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery to decrease the incidence of local and systemic recurrence. The German Rectal Cancer Study compared neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy and found improved outcomes with neoadjuvant chemotherapy[1]. This can be done in the form of a long course of chemoradiotherapy, a short course radiotherapy or TNT.

When TNT adjuvant chemotherapy is moved to the neoadjuvant setting and given preoperatively, it improves compliance, decreases treatment-associated toxicity, and results in tumor down staging leading to better sphincter preservation[16,17]. Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that there is no benefit to adjuvant chemotherapy in LARC and its use does not improve outcomes in patients with stage II and III disease who receive chemoradiation in the neoadjuvant setting[7-9]. The EORTC 22921 trial was conducted to evaluate the utility of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with T3-T4 tumors, and it found that there was no additional benefit of giving adjuvant chemotherapy to patients who had been treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation[6]. Patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy showed poor compliance with only 43%-73.6% of them receiving the planned doses and an overall delay of over 18 wk in receiving systemic therapy[3]. They also had higher incidence of chemotherapy related toxicity and poor surgical outcomes[4-9]. Prior studies have shown that over 10%-25% of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy have complete pathological response, which is an established predictor of improved survival[18-23] (Table 2).

| Treatment type | Protocol used |

| nCRT | 50-55Gy/25-28 fx with concurrent 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine1 |

| Post-op MaChT | Excisional surgery followed by postoperative (i.e. adjuvant) chemotherapy with 5-FU based regimens1 |

| TNT | 25-35Gy/5 fx followed by CAPOX or FOLFOX chemotherapy |

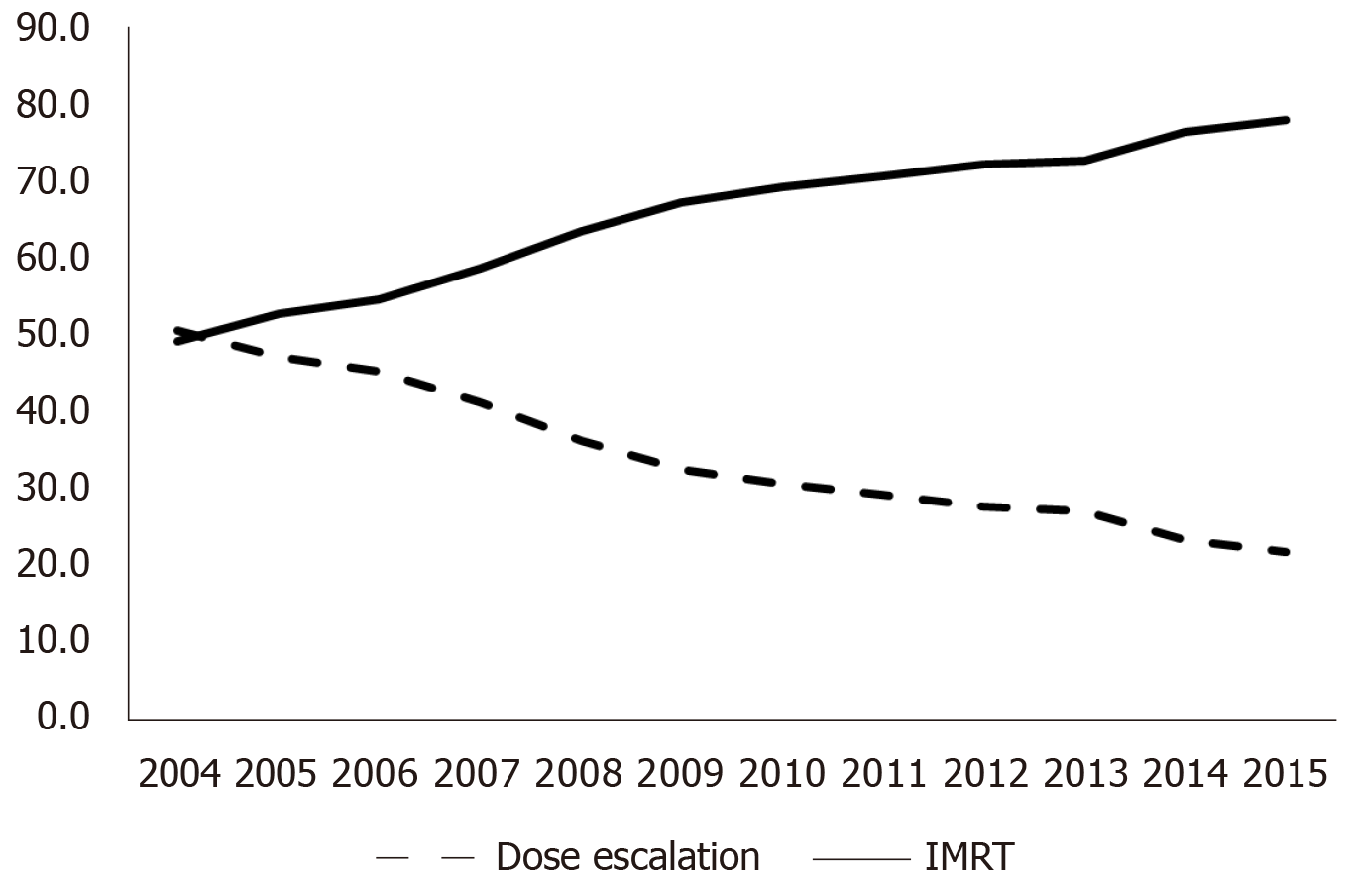

In light of these findings, the use of alternate treatment strategies such as TNT is gaining favor and its use is becoming increasingly common. Our data showed an increase in recent years in the use of TNT, which coincided with the initiation of several clinical trials evaluating the outcomes of using TNT over traditional CRT. The number of patients treated with TNT was small in our dataset, however, this was to be expected as it was compiled over 10 years from 2004 to 2015, and TNT use is a rather recent phenomenon. Our data showed a rising trend in TNT use, with patients diagnosed from 2013 to 2015 having the highest frequency of use. We expect this use to further increase as more data about benefits of TNT over traditional treatment comes to light.

Our study was a large analysis of multi-institutional data to compare the use of conventional chemoradiation with TNT. Due to the large sample size in this database, we were afforded the statistical power to conduct retrospective analyses of different treatment strategies. Our analysis of the NCDB database showed that there has been an increase in TNT use and this trend has been increasing in recent years. This trend was most apparent in patients with stage III disease (Figure 2).

The total number of patients who received TNT is comparatively much lower than the number of patients undergoing CRT, which was a possible limitation of our study. However as prospective data matures, we will see a greater number of patients being treated with TNT. There were limitations to our study, as the data collected by NCDB is retrospective; thus selection biases certainly existed. To counteract this possible bias, propensity score adjustment was performed. Second, as NCDB is coded, there is potential for incomplete coded or miscoded variables, which may have impacted our results and some statistics. One such variable is the incidence of colorectal cancer divided by gender. Per the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, men have a slightly increased lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (4.5%) compared to women (4.15%). This difference in risk may explain why as per the NCDB database, roughly 60% of our population was male compared to approximately 40% women. It is imperative to note that although the NCDB accounts for cancer treatment all over the United States, only about 70% of the patients treated for cancer are entered into the database; this may also explain why our population had a higher percentage of male patients.

In conclusion, this study was significant, despite its limitations, as it was a large-scale analysis of treatment selection for more than 70% of patients diagnosed with rectal cancer from 2004 to 2015 in the United States. It showed an increase in the use of TNT, concordant with current research demonstrating its benefits over the use of conventional neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The rate of use of TNT has been steadily increasing and is most prevalent in patients diagnosed with LARC in recent years. As clinical trials studying the use of TNT near completion, the benefits of this approach are becoming more widely accepted and the use of TNT is increasing.

Locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) treatment has been evolving for several years, specifically to improve standard of living after treatment. Total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT) has been gaining favor in recent years as it allows for better sphincter preservation and an overall improved quality of life. Our study analyzes the use of TNT over a 10-year period and compares the overall survival (OS) to that of patients treated with traditional neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

The focus of our study was to evaluate the OS in patients with LARC when treated with either TNT or traditional chemoradiation. It compared the two modes of treatment, which will help clinicians decide between the two modalities. It also sets up the stage for ongoing and future clinical trials that aim to study the benefit of using one modality over the other.

The main objective of our research was to analyze differences in OS in patients treated with TNT or traditional chemoradiation. We did not find a statistically significant difference in OS between the two modalities. An equivocal OS allows researchers to further design clinical trials comparing both treatment options prospectively and establish stronger guidelines that will further help clinicians decide what treatment will benefit their patients most.

This was a retrospective review of data extracted from the national cancer database. We queried the National Cancer Data Base to find patients with LARC, stages II and III, who were treated with either TNT or traditional chemoradiotherapy. The standard of care, currently, utilizes a combination of adjuvant chemoradiation and surgery, followed by postoperative multi-agent chemotherapy. We analyzed the differences in OS between the two arms as our primary goal. For our secondary goal, we established what patient characteristics were likely to be associated with TNT use. These characteristics included age, race, gender and comorbidity score.

Using univariate and multivariate cox regressions, we analyzed our data for both primary and secondary goals. There was no statistically significant difference in OS between the two arms. We also found that patients with stage III disease, higher nodal involvement or treatment within recent years were more likely to have been treated with TNT. Patients in both arms had poor OS with higher comorbidity score, older age, African American race and female gender. Our results further solidify the theory that TNT is non inferior to traditional chemoradiotherapy, and thus must be studied in more detail with prospective trials.

OS is similar in patients treated with either TNT or traditional chemoradiation. TNT has been associated with better quality of life. As OS is similar to that of neoadjuvant chemoradiation, using TNT may be preferable, to allow for a better standard of living. The 5-year OS is similar for both TNT and traditional chemoradiation. First, in patients with LARC, TNT and neoadjuvant chemoradiation have similar rates of OS. Second, TNT use may be linked to a better quality of life however more studies are needed in this area. There were no new methods as this was a retrospective review of a national database. There was no new phenomenon found as this was a retrospective analysis of an existing database. We queried the database to establish differences in OS for patients treated with two different chemoradiation protocols. Our retrospective analysis showed that the rate of OS was equivocal in patients treated with either TNT or traditional chemoradiation. It will allow clinicians and researchers to further compare the two modalities and may increase the treatment options available to patients suffering from LARC.

New techniques that allow for radiation treatment to be completed prior to surgery, such as TNT, have yielded non- inferior results and therefore must be studied in greater detail. Future research should aim to conduct prospective clinical trials comparing TNT to traditional chemoradiation. This will help clinicians better decide what treatment is best suited to their patient population. Clinical trials exploring the survival, quality of life and toxicities associated with both TNT and neoadjuvant chemoradiation will help further the research in this field and provide concrete answers to many of the questions raised.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Moschovi MA S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, Martus P, Tschmelitsch J, Hager E, Hess CF, Karstens JH, Liersch T, Schmidberger H, Raab R; German Rectal Cancer Study Group. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4342] [Cited by in RCA: 4449] [Article Influence: 211.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Petrelli F, Coinu A, Lonati V, Barni S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy after neoadjuvant treatment and surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:447-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Smith JJ, Garcia-Aguilar J. Advances and challenges in treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1797-1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sainato A, Cernusco Luna Nunzia V, Valentini V, De Paoli A, Maurizi ER, Lupattelli M, Aristei C, Vidali C, Conti M, Galardi A, Ponticelli P, Friso ML, Iannone T, Osti FM, Manfredi B, Coppola M, Orlandini C, Cionini L. No benefit of adjuvant Fluorouracil Leucovorin chemotherapy after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cancer of the rectum (LARC): Long term results of a randomized trial (I-CNR-RT). Radiother Oncol. 2014;113:223-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, Becker H, Raab HR, Villanueva MT, Witzigmann H, Wittekind C, Beissbarth T, Rödel C. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926-1933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1474] [Article Influence: 113.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Daban A, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC, EORTC Radiotherapy Group Trial 22921. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1114-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1993] [Cited by in RCA: 2035] [Article Influence: 107.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Glynne-Jones R, Counsell N, Quirke P, Mortensen N, Maraveyas A, Meadows HM, Ledermann J, Sebag-Montefiore D. Chronicle: results of a randomised phase III trial in locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation randomising postoperative adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus control. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1356-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Stojanovic-Rundic S, Bensadoun RJ, Bardet E, Beny A, Ollier JC, Bolla M, Marchal D, Van Laethem JL, Klein V, Giralt J, Clavère P, Glanzmann C, Cellier P, Collette L; EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: long-term results of the EORTC 22921 randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Breugom AJ, van Gijn W, Muller EW, Berglund Å, van den Broek CB, Fokstuen T, Gelderblom H, Kapiteijn E, Leer JW, Marijnen CA, Martijn H, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, Nagtegaal ID, Påhlman L, Punt CJ, Putter H, Roodvoets AG, Rutten HJ, Steup WH, Glimelius B, van de Velde CJ. Cooperative Investigators of Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group and Nordic Gastrointestinal Tumour Adjuvant Therapy Group. Adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision: a Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:696-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS, Roxburgh CS, Lynn P, Eaton A, Widmar M, Ganesh K, Yaeger R, Cercek A, Weiser MR, Nash GM, Guillem JG, Temple LKF, Chalasani SB, Fuqua JL, Petkovska I, Wu AJ, Reyngold M, Vakiani E, Shia J, Segal NH, Smith JD, Crane C, Gollub MJ, Gonen M, Saltz LB, Garcia-Aguilar J, Paty PB. Assessment of a Watch-and-Wait Strategy for Rectal Cancer in Patients With a Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e185896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Phang PT. Total mesorectal excision: technical aspects. Can J Surg. 2004;47:130-137. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Grass F, Mathis K. Novelties in treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. F1000Res. 2018;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gollins S, Sebag-Montefiore D. Neoadjuvant Treatment Strategies for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Winchester DP, Stewart AK, Bura C, Jones RS. The National Cancer Data Base: a clinical surveillance and quality improvement tool. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. |

| 16. | Wang X, Yu Y, Meng W, Jiang D, Deng X, Wu B, Zhuang H, Wang C, Shen Y, Yang L, Zhu H, Cheng K, Zhao Y, Li Z, Qiu M, Gou H, Bi F, Xu F, Zhong R, Bai S, Wang Z, Zhou Z. Total neoadjuvant treatment (CAPOX plus radiotherapy) for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer with high risk factors: A phase 2 trial. Radiother Oncol. 2018;129:300-305. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Azin A, Khorasani M, Quereshy FA. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: the surgeon's perspective. J Clin Pathol. 2019;72:133-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:918-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hartley A, Ho KF, McConkey C, Geh JI. Pathological complete response following pre-operative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: analysis of phase II/III trials. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:934-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vecchio FM, Valentini V, Minsky BD, Padula GD, Venkatraman ES, Balducci M, Miccichè F, Ricci R, Morganti AG, Gambacorta MA, Maurizi F, Coco C. The relationship of pathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) and outcomes after preoperative therapy in rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:752-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Valentini V, Coco C, Picciocchi A, Morganti AG, Trodella L, Ciabattoni A, Cellini F, Barbaro B, Cogliandolo S, Nuzzo G, Doglietto GB, Ambesi-Impiombato F, Cosimelli M. Does downstaging predict improved outcome after preoperative chemoradiation for extraperitoneal locally advanced rectal cancer? A long-term analysis of 165 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:664-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rödel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, Füzesi L, Klimpfinger M, Fietkau R, Liersch T, Hohenberger W, Raab R, Sauer R, Wittekind C. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8688-8696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 918] [Cited by in RCA: 949] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Quah HM, Chou JF, Gonen M, Shia J, Schrag D, Saltz LB, Goodman KA, Minsky BD, Wong WD, Weiser MR. Pathologic stage is most prognostic of disease-free survival in locally advanced rectal cancer patients after preoperative chemoradiation. Cancer. 2008;113:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |