Published online Feb 16, 2010. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i2.69

Revised: January 12, 2010

Accepted: January 19, 2010

Published online: February 16, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms.

METHODS: Between July 2007 and March 2009, 27 consecutive superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms in 25 enrolled patients were treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. The therapeutic efficacy, complications, and follow-up results were assessed.

RESULTS: The mean size of the lesions was 21 ± 13 mm (range 2-55 mm); the mean size of the resection specimens was 32 ± 12 mm (range 10-70 mm). The en block resection rate was 100% (27/27), and en block resection with tumor-free lateral/basal margins was 88.9% (24/27). Perforation occurred in 1 patient who was managed by conservative medical treatments. None of the patients developed local recurrence or distant metastasis in the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic submucosal dissection is applicable to superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms with promising results.

- Citation: Nonaka K, Arai S, Ishikawa K, Nakao M, Nakai Y, Togawa O, Nagata K, Shimizu M, Sasaki Y, Kita H. Short term results of endoscopic submucosal dissection in superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(2): 69-74

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v2/i2/69.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v2.i2.69

There is a considerable increase in the number of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms (SCNs) indicated for local treatment thanks to the recent development in endoscopy, including magnifying endoscopy by using narrow-band imaging (NBI) and iodine staining[1,2]. Noninvasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ, m1) and intramucosal invasive carcinoma limited to the lamina propria mucosae (m2) without vessels infiltration, have proved to have no lymph node or distant metastases. This hase been shown by a large number of retrospective histopathological analyses of surgically resected esophageal SCNs, and, as a result, endoscopic therapy may be considered as treatment option for these lesions.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has been accepted widely for localized SCNs as an alternative to surgical therapy, especially in Japan, because of the considerable rates of surgical mortality and postsurgical complications related to esophagectomy (range 2.1% to 13.7%), that result in poor patient quality-of-life[3-5]. The long-term outcomes after EMR of esophagus squamous cell carcinomas show similar effectiveness compared with surgical therapy for early-stage neoplasms[6,7]. However, conventional EMR techniques are limited in resection size, and therefore large lesions need to be resected in multiple fragments.

In recent years, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been developed as a method to resect larger lesions, as it enables precise resection irrespective of the size and shape of the lesions[8-12]. On the other hand, ESD may be associated with technical difficulty and a higher incidence of complications. Although ESD is widely accepted as a more reliable therapeutic procedure for large superficial gastric cancer in Japan[13-16], few studies have elucidated the technical feasibility of this procedure in the esophagus[16]. This study set out to evaluate the efficacy, safety and short-term follow-up outcomes of ESD for esophageal SCNs.

From July 2007 through March 2009, twenty-seven consecutive superficial esophageal SCNs, occurring in 25 patients, underwent ESD at the Saitama Medical University International Medical Center, Saitama, Japan. Diagnosis was made by using chromoendoscopy with iodine staining, NBI, and endoscopic biopsy. Endoscopic ultrasonography was also indicated for lesions suspected of submucosal invasion. All 25 patients were confirmed to have no lymph-node metastasis by CT before the treatment. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. 22 SCNs, preoperatively diagnosed as high-grade intraepithelial neoplasm (high-grade dysplasia and noninvasive carcinoma; m1) or intramucosal invasive carcinoma (m2), were primary indicated for ESD. Although the majority of the lesions were m2 or superficial infiltrations, in 4 SCNs, a small portion of m3 (invasive to the muscularis mucosae) to sm1 (less than 200 μm below the muscularis mucosae) infiltration was suspected. ESD was also chosen in these 4 patients after informed consent was obtained. This was based on the patients’ strong wish and to avoid risks associated with esophagectomy/chemoradiotherapy (CRT), because of the presence of accompanying diseases. In the remaining 1 patient, EUS and NBI-magnified observation suggested sm2 infiltration (more than 200 μm below the muscularis mucosae). This patient had already undergone EMR and radiotherapy several times for this lesion, and difficult endoscopic resection was expected for the local recurrent lesion due to fibrosis. However, ESD was chosen in this case, in accordance with the patient’s strong wish.

ESD procedures were performed by using video endoscopes (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Detail of the procedure has been described elsewhere[17-19]. In brief, normal saline was pre-injected into the submucosal layer of the esophagus to avoid subsequent injections of sodium hyaluronate solution into an inappropriate layer. Sodium hyaluronate (0.5%) was then injected to make a good protrusion of the targeted mucosa. By mixing a small amount of dye, the sodium hyaluronate can be distinguished easily from the non-injected area even after the pre-injection of normal saline. A small amount of epinephrine was also mixed with sodium hyaluronate to diminish bleeding during the procedures. A, mucosal incision around the tumor was then made with either a flash knife (KD-2618 JN-15; Fujinon) or flex knife (KD-630L; Olympus). The knife was gently pressed onto the mucosa. The distal half of the mucosal incision was completed first, followed by the proximal half. A hood, 4 mm in length attached at the endoscope tip, was also helpful for the safety of mucosal incision by blocking unintentional movements of the esophageal wall toward the knife.

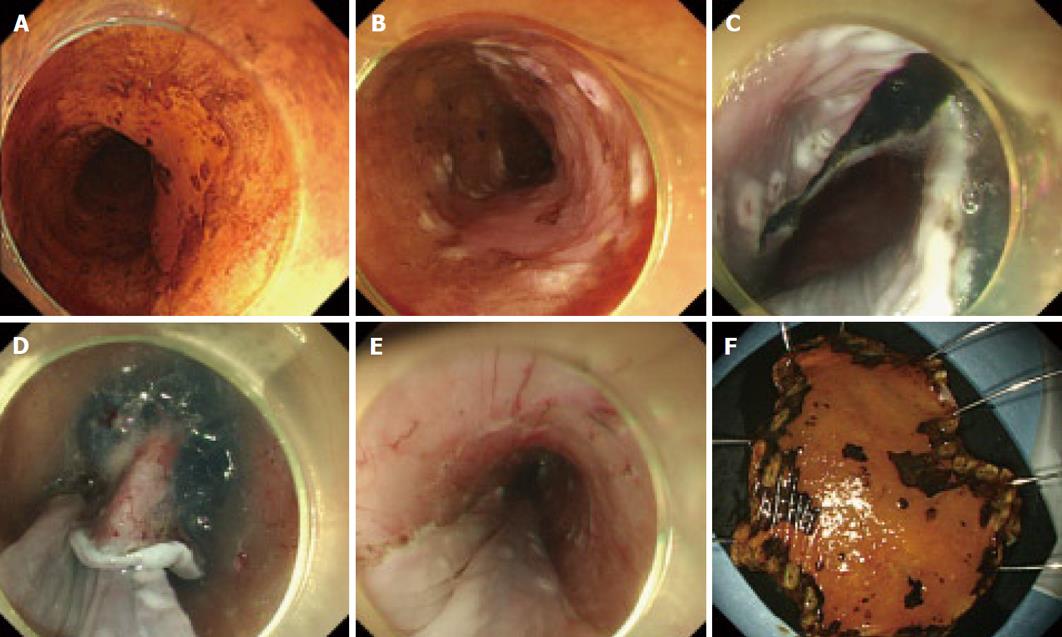

Before incising the entire circumference of the lesion, dissection of the submucosa was started from the area in which the mucosal incision was completed, prior to the flattening of the lifted area as the procedure progressed. The principal knife used for the submucosal dissection was the same one as that used for the mucosal incision. A hook knife (KD-620LR; Olympus) was also used in combination with the principal knife in difficult dissections. The operation time was recorded for all the procedures. A typical example is shown in Figure 1.

In our department, a flex knife (KD-630L; Olympus) was used in 15 patients who were treated before June 2008. We then switched to a flash knife, of 1.5 mm in tip length, in all the patients since July 2008. A water-pumping function at the knife tip is employed in the flash knife, facilitating the removal of tissues such as lesions adhered to the tip during treatment without requiring knife extraction/insertion from/into a scope. In addition, saline employed for water pumping at the tip facilitates additional topical injection into the submucosal layer. This reduces time loss related to the frequent extraction/insertion of an injection needle for the additional topical injection of sodium hyaluronate. ESD of esophageal lesions was performed under general anesthesia managed by anesthesiologists in the operating room in 15 patients. In 10 patients, in who the resection was not expected to be difficult, the lesions were treated under conscious sedation with midazolam in the endoscopy room.

Histological evaluation of the resected specimen was performed according to the Paris classification and revised Vienna classification[20-22]. The specimens, fixed by formalin, were cut into 2-mm slices. They were examined microscopically for histological type, depth on invasion (m1, m2, m3, sm1, sm2, sm3), lateral resection margin, and vertical resection margin.

Additional treatment was recommended for patients who had a histopathological diagnosis of invasive carcinoma deeper than the lamina propria mucosae (m3), or sm and/or vessel infiltration or incomplete resection on the basal margins, resection with non-evaluable tumor-free basal margins, or resection with tumor-exposed basal margins. Recommended treatments included CRT or radiation therapy alone for possible lymph node metastases or esophagectomy with lymph node dissection. In some cases the histopathological evaluation suggested that the lesions fulfilled the criteria of node-negative tumors but were resected incompletely on the lateral margins, resection with nonevaluable tumor-free lateral margins, or resection with tumor-exposed lateral margins. However, these patients were followed without additional treatments because the burn effects on the resected tissue sometimes made a precise histopathologic evaluation of the lateral margins difficult.

All patients who underwent ESD were regularly observed with half-yearly endoscopic examinations to check for local recurrence and/or a 2nd primary lesion as well as CTs to evaluate the existence of distant or lymph node metastases.

Some variables in this study were described as mean (SD). All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The P value was 2 sided, and P < 0.05 was used to determine statistical validity.

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1. The mean (SD) size of the lesions was 21 ± 13 mm (range 2-55 mm); the mean (SD) size of the resection specimens was 32 ± 12 mm (range 10-70 mm). All the lesions were resected in an en bloc fashion. En bloc resection with tumor-free lateral/basal margins was accomplished in 24 of the 27 dissected lesions (88.9%). 24 lesions (88.9%) were located in the thoracic esophagus. Twenty-one lesions (77.8%) (1 dysplasia, 6 mL, and 12 m2) in 19 patients were considered node-negative tumors by histopathological evaluations of the resected specimens. The mean procedure time of ESD was 88 ± 65 min (range 20-300 min). Minor bleeding was encountered in all the dissections when incising the mucosa or dissecting the submucosal layer and hemostasis was achieved with thermocoagulation without the use of clips. No patient experienced massive hemorrhage requiring a blood transfusion or a postprocedure emergency endoscopy. Perforation, diagnosed by endoscopic findings of tearing of the proper muscle layer, occurred in 1 lesion. In this case, ESD was completed after closing the perforation site via endoscopic clipping. Fever and thoracic pain was noted after the surgery and this patient was cured conservatively. Three lesions in 3 patients required several sessions of periodic balloon dilation for esophageal stricture after ESD. The postprocedure stricture was successfully managed endoscopically in all cases. None of the patients developed local recurrence or distant metastasis in the follow-up period. By preoperative examination, 7 lesions were diagnosed as m1, 15 lesions as m2, 2 lesions as m3, 2 lesions as sm1, and 1 lesion as sm2. Histopathological diagnosis of esophageal SCNs after ESD were m1 in 6 lesions, m2 in 14 lesions, m3 in 4 lesions, sm2 in 2 lesions, and dysplasia in 1 lesion. The overall accuracy rate for depth of invasion was 62.9%.

| Number of lesions | ||

| Location | Ce/Ut/Mt/Lt/Ae | 3/12/9/3/0 |

| En block resection rate | 100% (27/27) | |

| Tumor-free lateral margin rate | 88.9% (24/27) | |

| Tumor-free basal margin rate | 92.6% (25/27) | |

| Tumor-free lateral/basal rate | 96.3% (26/27) | |

| Mean tumor size [mean (SD)], mm (range) | 21 ± 13 mm (2-55) | |

| Mean specimen size [mean (SD)], mm (range) | 32 ± 12 mm (10-70) | |

| Macroscopic type | IIa/IIb/IIc/IIc + IIb | 2/5/19/3 |

| Preoperative determining depth of invasion of SCNs | m1/m2/m3/sm1/sm2 | 7/15/2/2/1 |

| Histologic depth | Dysplasia/m1/m2/m3/sm1/sm2 | 1/6/14/4/0/2 |

| Vessel infiltration (+) | 2 | |

| Procedure time [mean (SD)], min | 88 ± 65 min | |

| Local recurrence | 0 | |

| Complication (perforation) | 1 | |

| The mean hospital length of stay | 9 d | |

| Balloon dilation (+) | 3 |

Of the 8 lesions in 8 patients with concomitant risks of nodal metastases, 5 lesions in 5 patients were closely followed up without additional treatment, at the patient’s decision. These included 3 with cancer infiltration in the muscularis mucosae (m3), one with m1 carcinoma in whom the horizontal stump was positive for tumor cells, and one with m2 carcinoma and lymphatic vessel infiltration, which increased the possibility of nodal metastasis. In one case with m3 infiltration, hypopharyngeal cancer was detected, and CRT was performed. In one case with sm infiltration in whom the horizontal stump was positive for tumor cells, additional surgery was conducted. In another case with sm infiltration in whom the vertical stump was positive for tumor cells, RT was performed. In 25 patients who underwent ESD (27 lesions), the mean admission period required for ESD was 9 d.

In our study, 3 cases developed stenosis and required dilatation after ESD. The lesions in these three cases were large,, covering more than 3/4 of the circumference of the middle thoracic esophagus. Although ESD facilitates en bloc resection regardless of the size, wide lesions covering more than 3/4 of the circumference require frequent dilatation This may reduce the patient’s quality of life and, therefore, for larger lesions in the esophagus caution is required before carrying out endoscopic therapy.

As shown in Table 2, we compared 15 lesions in which ESD was performed under general anesthesia managed by anesthesiologists, with 12 lesions treated under conscious sedation. The mean lesion size was 26.9 mm in patients who underwent ESD under general anesthesia and 15.1 mm under conscious sedation This significant difference was not unexpected because the choice of anaesthesia was based on the expected level of difficulty, including tumor size. There was no significant difference in the duration of surgery, incidences of complications, and mean admission period between the two groups.

| General anesthesia | Intravenous anesthesia | P value | |

| Mean tumor size (mm) | 26.9 | 15.1 | P < 0.05 |

| Procedure time (min) | 98 | 75 | NS |

| Complication (perforation) | 0 | 1 | NS |

| The mean hospital length of stay (day) | 9.6 | 8.4 | NS |

Finally, we compared 15 lesions in which ESD was performed by using a flex knife, with 12 lesions treated by using a flash knife. As shown in Table 3, there is no significant difference between the two groups in the mean lesion size, duration of surgery, incidences of complications, and the rate of en-block resection.

| Flex knife | Flush knife | P | |

| Mean tumor size (mm) | 20 | 23 | NS |

| Procedure time (min) | 78 | 100 | NS |

| Complication (perforation) | 0 | 1 | NS |

| En block resection rate (%) | 100 | 100 | NS |

In the field of gastric cancer treatment, ESD is increasingly employed following rapid technical advances. By contrast, in the field of esophageal cancer treatment, the development of ESD has been hampered because the esophageal wall is thin and perforation is a frequent complication of ESD. This can result in worsening of the patient’s condition should mediastinitis develop. In addition, favorable mucosal mobility facilitates the resection of lesions measuring 2 cm or less using conventional EMR[23-25]. However, the risk of residual tumor/relapse is increased after EMR in lesions measuring 2 cm or more. In these lesions, residual tumor/relapse is associated with the number of the resected sections, and not with the size or circumference. In our data, the rate of en-block resection was 100%. This suggests that ESD could overcome the risk of residual tumor/relapse associated with EMR.

Although the duration of follow-up is short, the present study also shows that no patient with esophageal SCNs, that met the criteria of node-negative tumors after the treatment with ESD, experienced recurrence extraluminally. Our data suggest that ESD can be a successful treatment for esophageal SCNs fulfilling the criteria of node-negative tumors. Furthermore, given the lack of complications, ESD can be considered to be a relatively safe procedure. The operative mortality rate was zero, and the only postoperative complication was benign stricture of the esophagus that could successfully be treated with balloon dilatation. Although 1 patient had small perforations, this was managed successfully without surgical rescue.

As esophageal surgery is invasive, postoperative management in the intensive care unit is required for a few days. A study reported that the mean admission period in patients undergoing esophagogastrectomy for ECJ lesions was 13.5 d[5]. Other studies indicated that the mean admission period in patients undergoing minimally invasive esophagectomy for esophageal neoplasms was 7 to 8 d[26,27]. ESD has considerable advantages over surgery, considering the high esophagectomy-related mortality rate and patient’s reduced quality of life after surgery[4,5,26,27]. In our study, the mean admission period was 9 d ESD was performed on more than half of the patients under general anesthesia, in whom the resection was expected to be difficult. However, they returned to a standard ward after the treatment, and were discharged after ESD, in a similar way to those conducted under conscious sedation. From a medico-economic viewpoint, the mean admission period in patients undergoing ESD for esophageal SCNs can be further shortened and this can also contribute to the advantage of ESD over surgery. In this study, there were no significant differences between the flex knife and flush knife used for ESD in relation to duration of surgery, the incidence of complications, and the rate of en-block resection, although different knives may potentially have different characteristics.

The local recurrence rate after esophageal EMR was reported to be as high as 20% because en bloc resection by EMR was difficult and required multiple resection for large lesion[24]. Moreover, a high incidence (21%) of complications in esophageal EMR (perforation and hemorrhage) has been reported[28]. In our ESD cases, the outcomes were markedly favorable as complication occurred in only one patient and the en bloc resection rate was 100%. These findings suggest that ESD is safer and more useful than EMR.

In conclusion, our study shows that ESD is a feasible technique for the resection of esophageal SCNs. Accumulation of the further cases is necessary before ESD can be widely accepted as a standard treatment for esophageal SCNs.

Endoscopic en bloc resection of superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms is difficult.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is applicable to esophagus superficial tumors.

The results of ESD in 25 esophageal cancer patients (27 lesions) were analyzed. A very high en bloc resection rate and high-level safety of the procedure were demonstrated.

ESD facilitated the safe en bloc resection of superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms regardless of the size.

Although small sample size might hamper the merits of this study, there are few studies indicating the results of ESD in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Peer reviewer: Seong Woo Jeon, Assistant Professor, Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, 50 Samduk-2Ga, Chung-gu, Daegu 700-721, South Korea

| 1. | Mandard AM, Tourneux J, Gignoux M, Blanc L, Segol P, Mandard JC. In situ carcinoma of the esophagus. Macroscopic study with particular reference to the Lugol test. Endoscopy. 1980;12:51-57. |

| 2. | Endo M, Takeshita K, Yoshida M. How can we diagnose the early stage of esophageal cancer? Endoscopic diagnosis Endoscopy. 1986;18 Suppl 3:11-18. |

| 3. | Makuuchi H. Endoscopic mucosal resection for mucosal cancer in the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:445-458. |

| 4. | McCulloch P, Ward J, Tekkis PP. Mortality and morbidity in gastro-oesophageal cancer surgery: initial results of ASCOT multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327:1192-1197. |

| 5. | Karl RC, Schreiber R, Boulware D, Baker S, Coppola D. Factors affecting morbidity, mortality, and survival in patients undergoing Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2000;231:635-643. |

| 6. | Shimizu Y, Tsukagoshi H, Fujita M, Hosokawa M, Kato M, Asaka M. Long-term outcome after endoscopic mucosal resection in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invading the muscularis mucosae or deeper. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:387-390. |

| 7. | Fujita H, Sueyoshi S, Yamana H, Shinozaki K, Toh U, Tanaka Y, Mine T, Kubota M, Shirouzu K, Toyonaga A. Optimum treatment strategy for superficial esophageal cancer: endoscopic mucosal resection versus radical esophagectomy. World J Surg. 2001;25:424-431. |

| 8. | Yamamoto H, Yube T, Isoda N, Sato Y, Sekine Y, Higashizawa T, Ido K, Kimura K, Kanai N. A novel method of endoscopic mucosal resection using sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:251-256. |

| 9. | Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560-563. |

| 10. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. |

| 11. | Oyama T, Kikuchi Y. Aggressive endoscopic mucosal resection in the upper GI tract£Hook knife EMR method. Min Invas Ther&. Allied Technol. 2002;11:291-295. |

| 12. | Yahagi N, Fujishiro M, Kakushima N, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Oka M, Iguchi M, Enomoto S, Ichinose M, Niwa H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using the tip of an electro-surgical snare (thin type). Dig Endosc. 2004;16:34-38. |

| 13. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. |

| 14. | Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221-226. |

| 15. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Satoh K, Kaneko Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Success rate of curative endoscopic mucosal resection with circumferential mucosal incision assisted by submucosal injection of sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:507-512. |

| 16. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Ono S, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A, Shimizu Y, Oka M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:688-694. |

| 17. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Satoh K, Kaneko Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Success rate of curative endoscopic mucosal resection with circumferential mucosal incision assisted by submucosal injection of sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:507-512. |

| 18. | Yamamoto H, Kita H. Endoscopic therapy of early gastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:909-926. |

| 19. | Kita H, Yamamoto H, Miyata T, Sunada K, Iwamoto M, Yano T, Yoshizawa M, Hanatsuka K, Arashiro M, Omata T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using sodium hyaluronate, a new technique for en bloc resection of a large superficial tumor in the colon. Inflammopharmacology. 2007;15:129-131. |

| 20. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-S43. |

| 21. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fl茅jou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. |

| 23. | Ishihara R, Iishi H, Takeuchi Y, Kato M, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, Masuda E, Tatsumi K, Higashino K, Uedo N. Local recurrence of large squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus after endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:799-804. |

| 24. | Katada C, Muto M, Manabe T, Ohtsu A, Yoshida S. Local recurrence of squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus after EMR. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:219-225. |

| 25. | Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Hirakawa K, Nakamura S, Umeno J, Koga H, Yao T, Iida M. Risk factors for local recurrence of superficial esophageal cancer after treatment by endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2007;39:41-45. |

| 26. | Nguyen NT, Hinojosa MW, Smith BR, Chang KJ, Gray J, Hoyt D. Minimally invasive esophagectomy: lessons learned from 104 operations. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1081-1091. |

| 27. | Kilic A, Schuchert MJ, Pennathur A, Yaeger K, Prasanna V, Luketich JD, Gilbert S. Impact of obesity on perioperative outcomes of minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:412-415. |

| 28. | Noguchi H, Naomoto Y, Kondo H, Haisa M, Yamatsuji T, Shigemitsu K, Aoki H, Isozaki H, Tanaka N. Evaluation of endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial esophageal carcinoma. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10:343-350. |