Published online Feb 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i2.471

Peer-review started: October 12, 2021

First decision: November 17, 2021

Revised: November 19, 2021

Accepted: January 11, 2022

Article in press: January 11, 2022

Published online: February 27, 2022

Processing time: 132 Days and 17.4 Hours

It has been studied that fluctuating glucose levels may superimpose glycated hemoglobin in determining the risk for diabetes mellitus (DM) complications. While non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) remains a predominant cause of elevated transaminases in Type 2 DM due to a strong underplay of metabolic syndrome, Type 1 DM can contrastingly affect the liver in a direct, benign, and reversible manner, causing Glycogen hepatopathy (GH) - with a good prognosis.

A 50-year-old female with history of poorly controlled type 1 DM, status post cholecystectomy several years ago, and obesity presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Her vitals at the time of admission were stable. On physical examination, she had diffuse abdominal tenderness. Her finger-stick glucose was 612 mg/dL with elevated ketones and low bicarbonate. Her labs revealed abnormal liver studies: AST 1460 U/L, ALP: 682 U/L, ALP: 569 U/L, total bilirubin: 0.3mg/dL, normal total protein, albumin, and prothrombin time/ international normalized ratio (PT/INR). A magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrated mild intra and extra-hepatic biliary ductal dilation without evidence of choledocholithiasis. She subsequently underwent a diagnostic ERCP which showed a moderately dilated CBD, for which a stent was placed. Studies for viral hepatitis, Wilson’s Disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin, and iron panel came back normal. Due to waxing and waning transaminases during the hospital course, a liver biopsy was eventually done, revealing slightly enlarged hepatocytes that were PAS-positive, suggestive of glycogenic hepatopathy. With treatment of hyperglycemia and ensuing strict glycemic control, her transaminases improved, and she was discharged.

With a negative hepatocellular and cholestatic work-up, our patient likely had GH, a close differential for NASH but a poorly recognized entity. GH, first described in 1930 as a component of Mauriac syndrome, is believed to be due to glucose and insulin levels fluctuation. Dual echo magnetic resonance imaging sequencing and computed tomography scans of the liver are helpful to differentiate GH from NASH. Still, liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Biopsy predominantly shows intra-cellular glycogen deposition, with minimal or no steatosis or inflammation. As GH is reversible with good glycemic control, it should be one of the differentials in patients with brittle diabetes and elevated transaminases. GH, however, can cause a dramatic elevation in transaminases (50-1600 IU/L) alongside hepatomegaly and abdominal pain that would raise concern for acute liver injury leading to exhaustive work-up, as was in our patient above. Fluctuation in transaminases is predominantly seen during hyperglycemic episodes, and proper glycemic control is the mainstay of the treatment.

Core Tip: Glycogen hepatopathy is a poorly understood complication of type 1 diabetes mellitus patients who have poor glycemic control. Its presentation can closely mimic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease creating a diagnostic enigma in patients with diabetes. After excluding other common causes of hepatitis, one must keep this elusive diagnosis in mind. Hepatic biopsy has been the mainstay for diagnosis, however, with recent advancements sequential magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans are also sensitive but limited by availability.

- Citation: Singh Y, Gurung S, Gogtay M. Glycogen hepatopathy in type-1 diabetes mellitus: A case report. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(2): 471-478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i2/471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i2.471

Ensemble of poorly controlled type 1 diabetics presenting with marked elevation in serum aminotransferases that corresponds with serum glucose fluctuation, and the defining histological changes on liver biopsy help clinch the diagnosis of glycogenic hepatopathy (GH)[1]. GH was first defined by Mauriac in a child with brittle diabetes. It was considered as a component of Mauriac syndrome, accompanied by delayed development, hepatomegaly, cushingoid appearance, and delayed puberty[2]. Additionally, GH can also be observed in adult type 1 diabetic individuals without other components of Mauriac syndrome[3,4]. Hyperglycemia and corresponding spike in insulin levels are believed to be the main culprits in GH. The treatment of GH is via establishing glycemic control. Often these findings in patients with diabetes may be dismissed as NAFLD; however, rigorous glycemic control via intensive insulin therapy provides complete remission of clinical, laboratory, and histological abnormalities[5]. Here, a 50-year-old female with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus is presented with a discussion referenced to the medical literature.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea and fatigue

A 50-year-old female with a long-standing history of uncontrolled type 1 DM, presented with fatigue and nausea for a day to a local hospital, where a basic workup was unrevealing, and she was discharged on symptomatic management. Her symptoms progressed and she began experiencing concomitant abdominal pain and diarrhea. Following this, she presented to our emergency room, with the above symptoms. Her abdominal pain was 6/10 in severity, cramping in nature that was relieved on lying down and predominantly on the left half. She did not have pruritus, jaundice, night sweats, fever, easy bruising, or bleeding. A review of systems was negative for headaches, chest discomfort, chest pain, shortness of breath, orthopnea, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. In an initial interview, she mentioned that she was admitted 6 mo ago with similar symptoms and at that time her appendix was removed. The prior hospital course was complicated by elevated liver function tests according to the patient. A list of medications at the time of admission included amlodipine, aspirin (low dose-81mg)), gabapentin, insulin glargine, and lispro (was not taking it for 2 days prior to presentation), metoprolol succinate, oxycodone, and pravastatin (taking a statin for several years, low dose).

Type 1 DM complicated by peripheral neuropathy, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic gastroparesis, coronary artery disease, deep vein thrombosis, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Personal history: Currently not working, Nonsmoker, never smoked, no vaping used, denied alcohol intake, denied recreational drug use.

Family history: Type 1 diabetes in aunt; Type 2 diabetes in both parents; Fatty liver disease in both parents and aunt.

The patient was obese, anicteric not in acute distress. She was afebrile; her pulse was 80 beats per minute, blood pressure 147/94 mmHg, BMI 31.39 kg/m², oxygen saturation 97% on room air. There was no elevation of jugular venous pressure. Examination of the heart and lungs was unremarkable. The abdomen was non-distended and soft, with normal bowel sounds. She had mild tenderness on palpation in the left lower quadrant with no rebound or guarding. Murphy's sign was absent. The liver was palpable 4 cm below the costal margin, with a measured span of 13 cm at the midclavicular line. The edge of the liver was smooth. The spleen was not palpable, and there was no evidence of ascites. There were no stigmata of chronic liver disease either including vesicular lesions, palmar erythema, pedal edema, or spider angiomata. The results of the neurologic examination, including mental status, were normal.

A workup for acute abdomen was initiated. Initial labs showed blood glucose: 610 mg/dL, AG: 13 U/L, CO2:23 ppm, pH: 7.35, and 1+ ketones in the urine. Diabetic ketoacidosis protocol ensued with insulin drip and IV fluids and frequent fingerstick glucose checks.

Hospital laboratory workup showed elevated liver enzymes viz. aspartate aminotransferase:1460 U/L, alanine aminotransferase: 682 U/L, alkaline phosphatase: 569 U/L, elevated LDH: 823 U/L, GGT:436 U/L total bilirubin 0.2 mg per deciliter, total protein 6.4 mg per deciliter, and albumin 3.7 g per deciliter. Levels of sodium were 135 mmol per liter, potassium 4.7 mmol per liter, chloride 103 mmol per liter, bicarbonate 20.9 mmol per liter, blood urea nitrogen 25 mg per deciliter, creatinine 0.85 mg per deciliter, and glucose 225 mg per deciliter. Amylase and lipase levels were normal. The white-cell count was 3900 per cubic millimeter, with an unremarkable differential count; hematocrit: 38.5%, hemoglobin: 10.9; and platelet count 221,000 per cubic millimeter. Levels of vitamin B12 and folic acid were normal. The international normalized ratio was 1.

Serum iron level was 76 µg per deciliter, total iron-binding capacity 384 μg per deciliter, ferritin 165 μg per liter, and thyroid stimulation hormone 0.71 μIU per liter. Her total cholesterol level was 122 mg per deciliter, triglycerides 104 mg per deciliter, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 49 mg per deciliter, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol 52 mg per deciliter. The glycated hemoglobin level was 11.4%. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 34 mm per hour. Serologic tests for viral hepatitis were negative for hepatitis B surface antibody, negative for hepatitis B surface antigen and core antibody, negative for hepatitis C antibody, negative for cytomegalovirus IgM+IgG antibody, negative for herpes simplex virus PCR. Tests for antimitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth-muscle antibody, and antinuclear antibody screen were negative. The serum ceruloplasmin and urinary copper levels were normal, as were the results of an ophthalmologic examination. The level of alpha1-antitrypsin was also normal. Salicylates, Tylenol levels, and a urine toxicology screen were all negative.

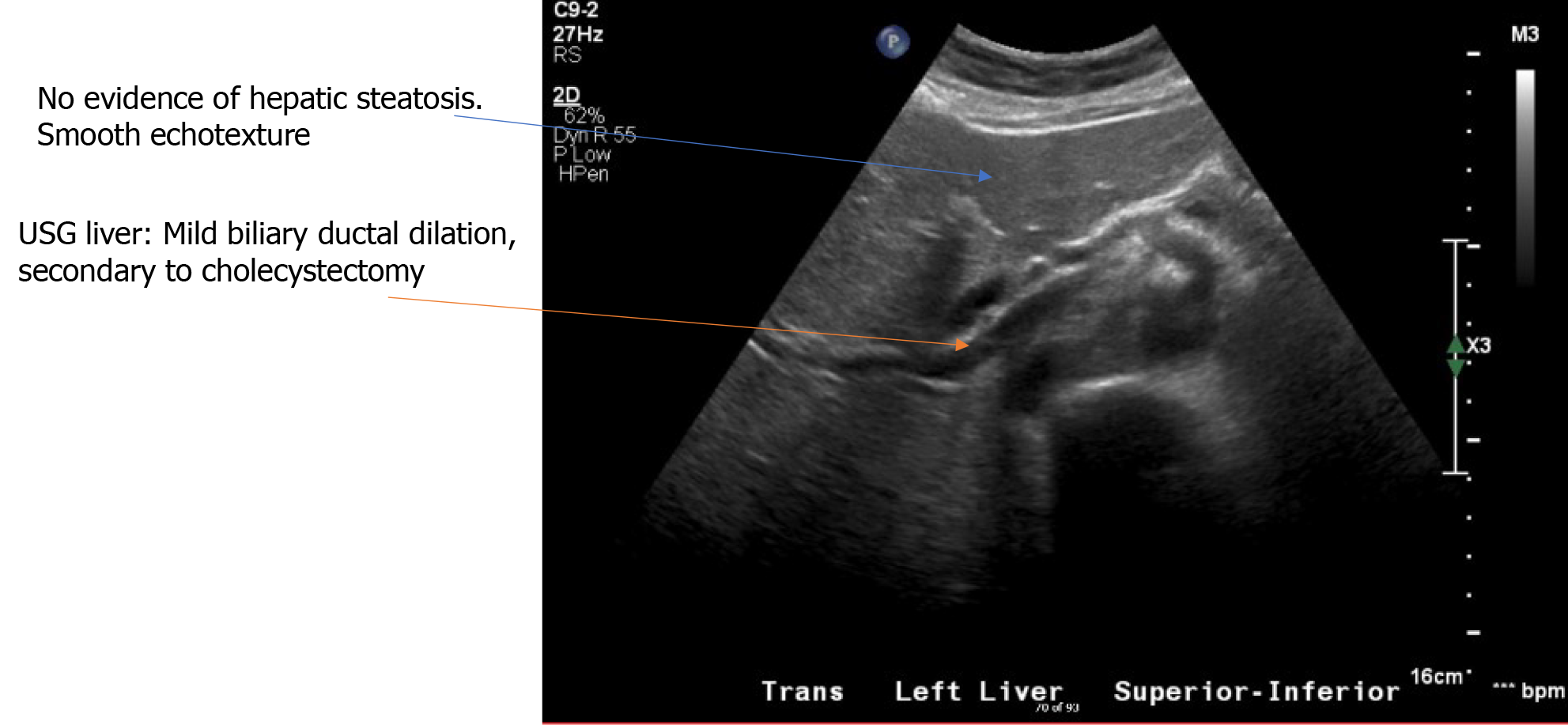

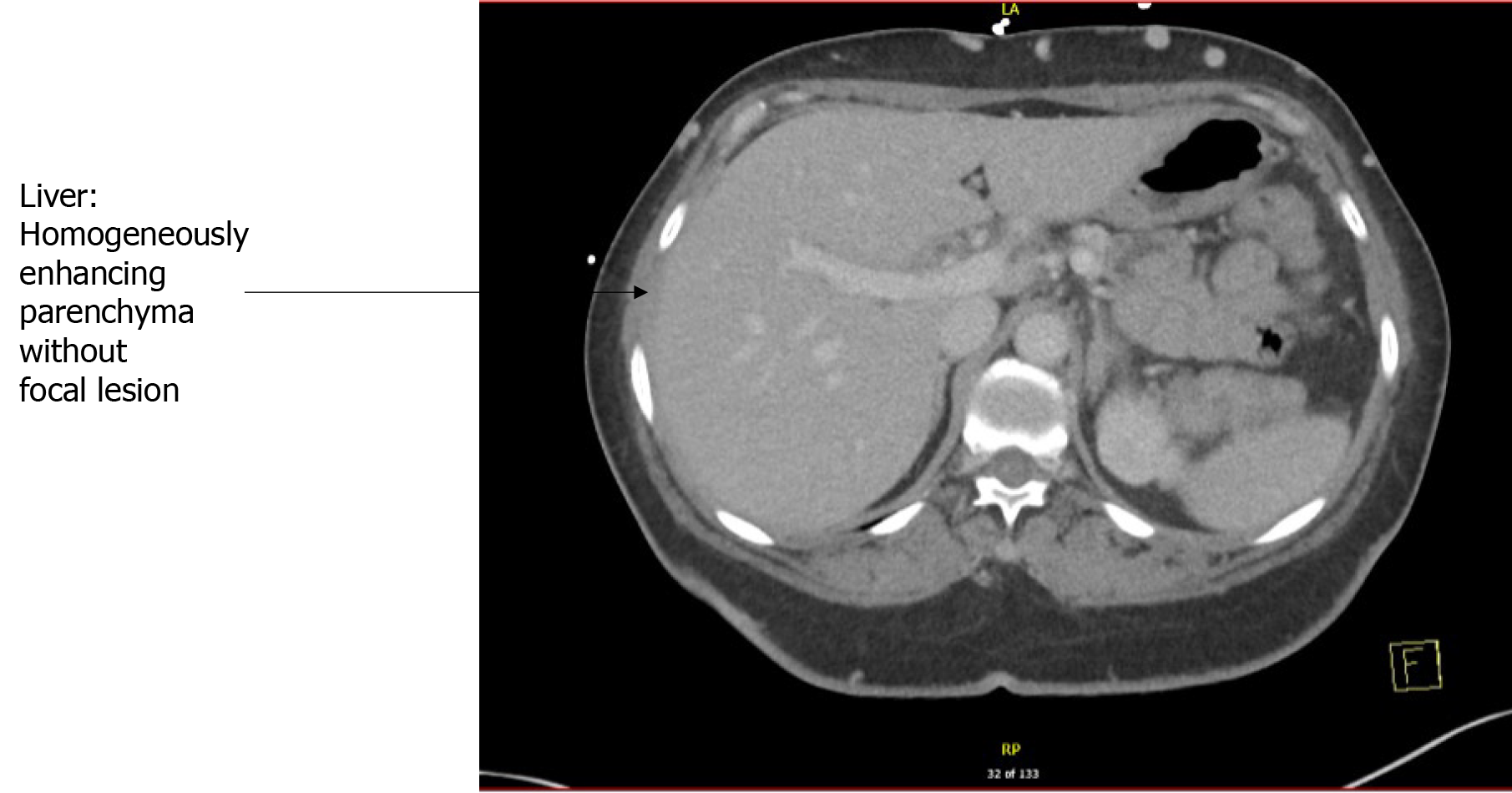

CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showed diffuse colonic wall thickening from previous involving the hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, and descending colon, suggestive of colitis. There was no pneumatosis or bowel obstruction or free air under the diaphragm. No focal hepatic lesions were seen either. There were post-cholecystectomy changes causing mild intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation without significant interval change. No obstructing calculus or lesions were visualized in the hepatobiliary system. The size, shape, and morphology of the liver, spleen, and pancreas were normal.

Doppler ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen showed a surgically absent gallbladder. The common bile duct measured 10 mm. There was mild central intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation, likely cholecystectomy related with nil fatty infiltration or vascular abnormalities, and normal echogenicity. An echocardiogram of the heart showed regular biventricular size with an ejection fraction of 65-70%.

Further, an MRCP showed mild intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilation without evidence of choledocholithiasis. There were no focal hepatic lesions. No diffuse parenchymal signal abnormality.

During the course of the hospital, it was noticed that initial rise in transaminases on admission, there was a sharp drop without any specific intervention. Strict glucose control ensued and hepatotoxic medications were held.

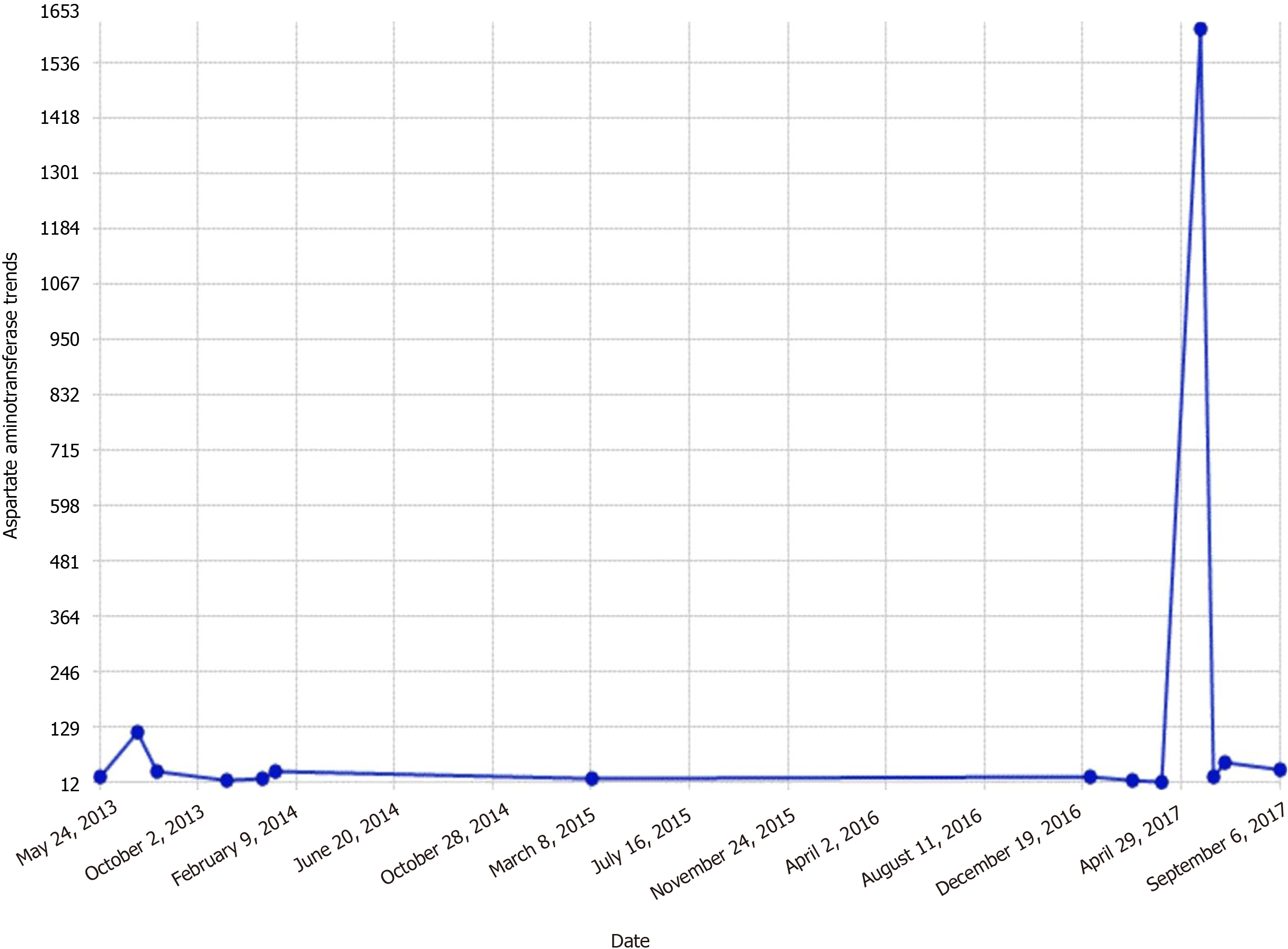

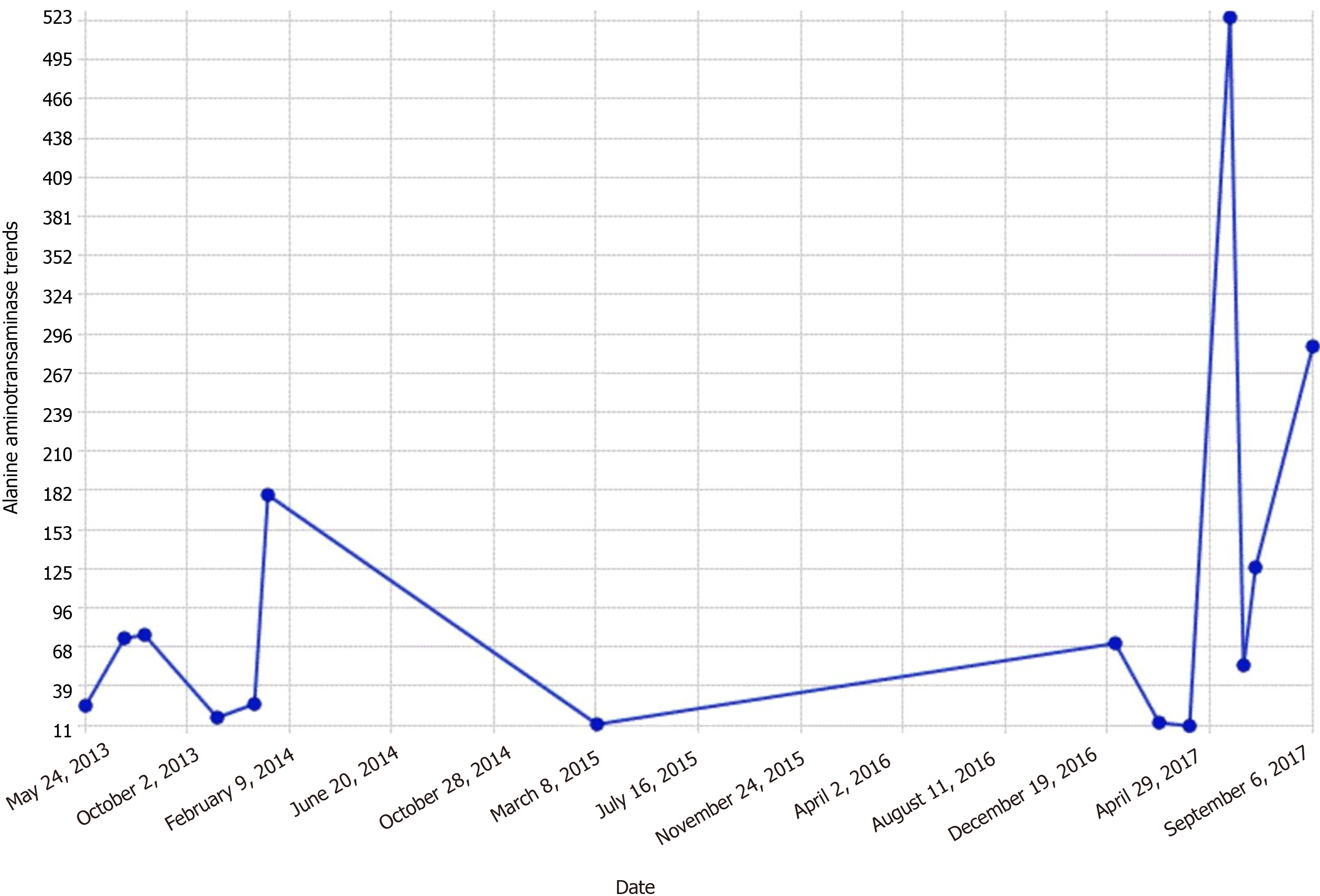

By the third day, transaminases dropped to the mid 300-400 range (Figures 1 and 2).

Due to the above negative results, a liver biopsy was pursued to clinch the diagnosis.

Liver biopsy showed a subset of hepatocytes, slightly enlarged with PAS-positive glycogen, suggestive of mild glycogenic hepatopathy. No significant glycogenated nuclei were seen - portal tracts with minimal inflammation composed of mononuclear cells, neutrophils, eosinophils with occasional ceroid-laden macrophages. A minority of bile ducts show mild epithelial injury. Bile ducts were present with focal mild bile ductular reaction (CK7 immunostain examined). No steatosis, cholestasis, hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, acidophil bodies, congestion, or confluent necrosis were identified. Trichrome stain showed no increased fibrosis. PAS/D stain is negative for intracytoplasmic globules. Iron stain is negative for iron deposition. A Gomori methenamine silver stain was negative for fungal organisms. Immunohistochemistry for CMV, HSV-1, HSV2, and adenovirus was negative. EBV-encoded RNA in situ hybridization was negative. The copper stain was negative. Reticulin stain showed an intact reticulin framework.

Glycogen hepatopathy secondary to poorly controlled type 1 DM.

With treatment targeting aggressive glycemic control with insulin and a strict carbohydrate-restricted diet, her transaminases improved. Her colitis resolved with conservative management following which, she was discharged.

The patient was advised to monitor blood sugars at home and was advised about the importance of a diabetic diet with the help of a diabetes educator. She was taught how to use an insulin pen, and was discharged with an insulin kit containing Insulin glargine (long-acting) along with Insulin lispro (short-acting to be taken with meals).

When she was seen a month later at the primary care physician's office, she was asymptomatic. Her laboratory tests revealed a normal biochemical profile, with transaminases well under the normal range.

The findings of increased liver enzymes have increased amongst patients with diabetes. The observation of increased alanine aminotransferase levels is 9.5% among type 1 as compared to 12.1% among type 2 diabetics. These percentages are higher than those expected in our general population (2.7%)[6,7]

A disease like GH develops due to hepatic glycogen accumulation. It is characterized by hepatomegaly and elevated liver function tests including AST and ALT[8,9]. GH was first defined as glycogen accumulation in 1930, as a component of Mauriac syndrome (type 1 diabetes, delayed development, hepatomegaly, cushingoid appearance, and delayed puberty)[2]. Interestingly, type 1 diabetic individuals without other components of Mauriac syndrome can have isolated manifestation of GH[10,3]. Type 1 diabetes patients formulate a major chunk of the case reports of this rare condition.

Elevated glucose levels with corresponding insulin spikes are believed to be metabolic preconditions for hepatic glycogen accumulation in GH. Hyperglycemia signals glycogen synthase by inhibiting glycogenesis by glycogen phosphorylation inactivation. Insulin also activates glycogen synthase which further increases glycogen accumulation[11]. A study conducted in rats with insulin deficiency has shown that glycogenesis continues for a significant amount of time after blood glucose levels return to the preinjection levels after a single dose of insulin injection[12]. In essence, accumulation of glycogen continues to occur in the liver, despite the high cytoplasmic glucose concentration in the presence of insulin. Hence, oscillating hyperglycemic episodes and the following insulin therapies to chase the elevated glucose levels are believed to be the primary pathogenetic mechanisms of hepatomegaly and abnormal liver chemistries that develop in T1DM patients due to glycogenic deposition. However, it is not clear why this pathogenetic mechanism develops specifically in a small patient group. Several theories have been proposed on the matter, one of which was the defect in genes coding the proteins that regulate the glycogen synthase and/or glucose 6-phosphatase activity[13]. Mainstay of managing GH is by establishing strict glycemic control via intensive insulin therapy. This modality of approach results in full remission of clinical, laboratory, and histologic abnormalities[5]. Several medical case reports exhibit remission in cases of GH by a continuous insulin infusion pump implanted under the skin[3]. Similarly, in our presented case, we attained blood glucose regulation, that was followed by a reduction in the liver size and significant decreases in ALT and AST levels using intensive insulin therapy.

Furthermore, after GH diagnosis, the treatment should aim for intense glycemic control as it is considered the backbone of its management[14-16]. Anomalously, the resolution of GH has also been described after minimal glucose control[15-17]. The disease has a benign course with an excellent prognosis and symptoms abate using above therapeutics within a few weeks, as also observed in our patient (Figure 3).

GH is a rare complication of diabetes mellitus, particularly in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients with poor glycemic control and the presentation can closely mimic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease creating a diagnostic enigma in patients with diabetes.

Clinicians should be aware of this rare complication of diabetes mellitus in T1DM patients with poor glycemic control.

After excluding other common causes of hepatitis, including viral and autoimmune hepatitis or celiac disease, an in-depth investigation for GH should be performed.

Liver biopsy has been the mainstay for diagnosis, however, with recent advancements, sequential magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (Figure 4) scans are also sensitive but limited by the availability.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Saint Vincent Hospital, American College of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nong X, Yuan G S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. |

Aljabri KS, Bokhari SA, Fageeh SM, et al Glycogen hepatopathy in a 13-year-old male with type 1 diabetes.

|

| 2. | CHAPTAL J, CAZAL P. A case of diabetes mellitus with obesity, dwarfism, infantilism and hepatomegaly; P. Mauriac syndrome; liver biopsy puncture. Montp Med. 1949;35-36:197. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Imtiaz KE, Healy C, Sharif S, Drake I, Awan F, Riley J, Karlson F. Glycogenic hepatopathy in type 1 diabetes: an underrecognized condition. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:e6-e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van den Brand M, Elving LD, Drenth JP, van Krieken JH. Glycogenic hepatopathy: a rare cause of elevated serum transaminases in diabetes mellitus. Neth J Med. 2009;67:394-396. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hudacko RM, Manoukian AV, Schneider SH, Fyfe B. Clinical resolution of glycogenic hepatopathy following improved glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22:329-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. |

Hyeon CK, Chung MN, Sun HJ, et al Normal serum aminotransferase concentration and risk of mortality from liver diseases: prospective cohort study.

|

| 7. | Lebovitz HE, Kreider M, and Freed MI. Evaluation of liver function in type 2 diabetic patients during clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:815-821. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torres M, López D. Liver glycogen storage associated with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Hepatol. 2001;35:538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Abaci A, Bekem O, Unuvar T, Ozer E, Bober E, Arslan N, Ozturk Y, Buyukgebiz A. Hepatic glycogenosis: a rare cause of hepatomegaly in Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chatila R, West AB. Hepatomegaly and abnormal liver tests due to glycogenosis in adults with diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Van Steenbergen W, Lanckmans S. Liver disturbances in obesity and diabetes mellitus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19 Suppl 3:S27-S36. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Thompson EW, Parks WC, Drake RL. Rapid alterations induced by insulin in hepatocyte ultrastructure and glycogen levels. Am J Anat. 1981;160:449-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roach PJ. Glycogen and its metabolism. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:101-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Khoury J, Zohar Y, Shehadeh N, Saadi T. Glycogenic hepatopathy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:113-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parmar N, Atiq M, Austin L, Miller RA, Smyrk T, Ahmed K. Glycogenic Hepatopathy: Thinking Outside the Box. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2015;9:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Silva M, Marques M, Cardoso H, Rodrigues S, Andrade P, Peixoto A, Pardal J, Lopes J, Carneiro F, Macedo G. Glycogenic hepatopathy in young adults: a case series. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:673-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chandel A, Scarpato B, Camacho J, McFarland M, Mok S. Glycogenic Hepatopathy: Resolution with Minimal Glucose Control. Case Reports Hepatol. 2017;2017:7651387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |