Published online May 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i5.230

Peer-review started: December 6, 2019

First decision: December 26, 2019

Revised: February 29, 2020

Accepted: April 4, 2020

Article in press: April 4, 2020

Published online: May 27, 2020

Processing time: 173 Days and 9.2 Hours

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide.

To describe the epidemiological profile and mortality rates of patients with ALD admitted to public hospitals in different regions of Brazil from 2006 to 2015.

This is a descriptive study that evaluated aggregate data from the five Brazilian geographic regions.

A total of 160093 public hospitalizations for ALD were registered. There was a 34.07% increase in the total number of admissions over 10 years, from 12879 in 2006 to 17267 in 2015. The region with the highest proportion (49.01%) of ALD hospitalizations was Southeast (n = 78463). The North region had the lowest absolute number of patients throughout the study period, corresponding to 3.9% of the total (n = 6242). There was a 24.72% increase in the total number of ALD deaths between 2006 and 2015. We found that the age group between 50 and 59 years had the highest proportion of both hospitalizations and deaths: 28.94% (n = 46329) of total hospital admissions and 29.43% (n = 28864) of all deaths. Men were more frequently hospitalized than women and had the highest proportions of deaths in all regions. Mortality coefficient rates increased over the years, and simple linear regression analysis indicated a statistically significant upward trend in this mortality (R² = 0.744).

Our study provides a landscape of the epidemiological profile of public hospital admissions due to ALD in Brazil. We detected an increase in the total number of admissions and deaths due to ALD over 10 years.

Core tip: Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. Many patients with ALD present for medical care after they have developed advanced liver disease and its complications. It is important to know the epidemiology of ALD within a specific region/country to better understand which resources might be necessary to improve management. This study provides a landscape of the epidemiological profile of hospital admissions due to ALD in different regions of Brazil from 2006 to 2015, including the mortality rates and admissions according to age range. We detected a 34.07% increase in the total number of hospital admissions for ALD and a 24.72% increase in the total number of ALD deaths over these 10 years. Therefore, this study signals the need to be alert to this liver illness and to possibly revisit policies related to alcohol marketing, sales, and consumption.

- Citation: Lyra AC, de Almeida LMC, Mise YF, Cavalcante LN. Epidemiological profile of alcoholic liver disease hospital admissions in a Latin American country over a 10-year period. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(5): 230-238

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i5/230.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i5.230

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. Alcohol is also a frequent co-factor in patients with other types of liver diseases, including hepatitis C virus infection among others. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality have wide geographical variation. Within each country, there is an excellent correlation between the level of alcohol consumption and the prevalence of alcohol-related injury. Individuals with long-term significant alcohol consumption remain at risk for liver disease that may range from alcoholic steatohepatitis to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[1-4].

Many patients with ALD present for medical care after they have developed advanced liver disease and its complications[1-4]. It is important to know the epidemiology of ALD within a specific region/country to better understand which resources might be necessary to improve management[5,6]. ALD might have been overlooked in recent years due to recent therapy advances in the viral hepatitis field. Therefore, few pharmacological developments have been made in the management of patients with this illness. Furthermore, ALD needs more than just a pharmacological intervention to be cured. It is also important to educate the population about the potential harm of alcohol usage. Given its high prevalence, economic burden, and clinical repercussions, ALD should receive significant attention from health authorities, research funding organizations, the population, and academic liver associations[1-3,7,8].

This study describes the epidemiological profile of hospital admissions due to ALD in different regions of Brazil from 2006 to 2015, including the mortality rates and admissions according to age range.

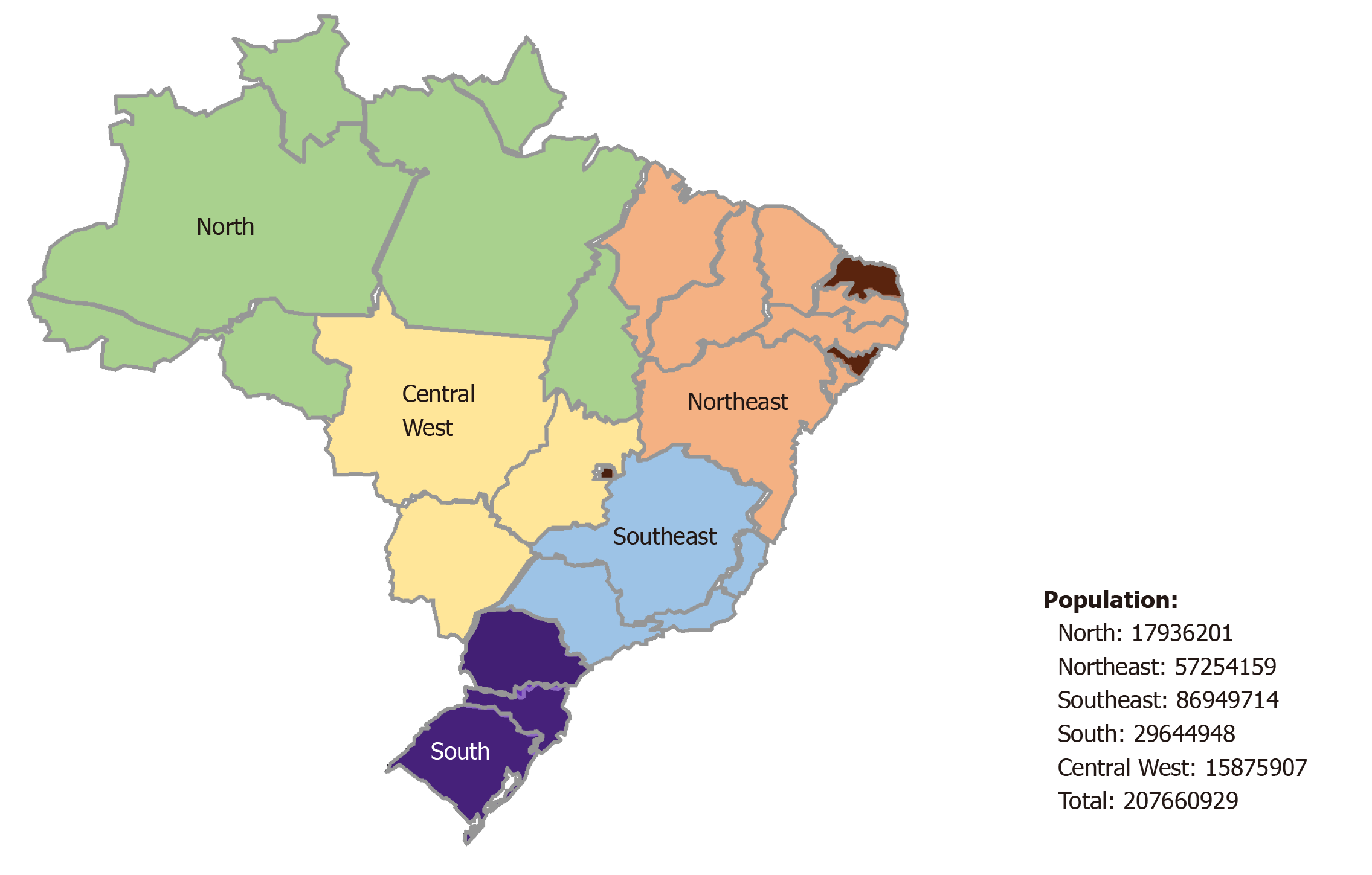

This is a descriptive study that evaluated aggregate data. Data from the five Brazilian geographic regions were used for the study (Figure 1).

The public health care information system (SUS hospital information system [SIH/SUS]) was used as the data source regarding admissions to public hospitals as well as death rates. It is available on the Ministry of Health online platform: http://www.datasus.gov.br[9]. Demographic data for the coefficient calculations were collected in an electronic database maintained by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (http://www.ibge.gov.br)[10]. Data from the period spanning 2006 to 2015 were analyzed.

For this study, all reported cases of ALD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision code K70) were evaluated. The analyzed variables were the number of hospitalizations (hospital admissions) and deaths due to ALD according to sex (male and female), age range (< 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80 years-old or more) and year (2006 to 2015). Data are presented as their absolute and relative values. The proportional distribution and mortality coefficient were used as indicators. Subsequently, the data were organized into spreadsheets and presented in tables and graphs using Microsoft Office Excel 2016. The ALD mortality coefficient per year and per region was calculated as follows: mortality coefficient = number of deaths/population × 100000. The analysis of temporal evolution of mortality from ALD in Brazil (2006 to 2015) was performed by describing the magnitude and fluctuations of this indicator during this period. Thereafter, the temporal trend in ALD mortality was evaluated using simple linear regression, with mortality from ALD as the dependent variable (Y) and the calendar year as the independent variable (X). The values of β, R², and P value were evaluated with SPSS version 21.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was performed according to Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council. Since this study was conducted using a secondary database in the public domain, which is available on the internet, it was not necessary to obtain written consent or approval from the Ethics and Research Committee. None of the authors have conflicts of interest.

During the period between 2006 and 2015, 160093 hospitalizations for ALD were registered. There was a 34.07% increase in the total number of hospital admissions for ALD in the Brazilian regions over these 10 years, from 12879 in 2006 to 17267 in 2015. The region with the highest proportion of hospitalizations during the study period was the Southeast, with 49.01% (n = 78463). Nevertheless, compared to the other regions, there was a decrease in this proportion from 2012 to 2015. The North region had the lowest absolute number of patients throughout the study period, corresponding to 3.9% of the total (n = 6242). The Midwest region experienced the greatest proportional increase over the years; this region accounted for 5.30% (n = 683) of hospitalizations in 2006 and increased to 8.70% (n = 1502) in 2015. The northeastern region had an increased number of hospitalizations from 2508 (19.47%) hospital admissions in 2006 to 3936 (22.79%) hospital admissions in 2015. The North region had a mild proportional increase from 3.14% (n = 404) in 2006 to 4.53% (n = 782) in 2015. On the other hand, although the South and Southeast regions also showed an increase in the total number of patients admitted to SUS hospitals over the analyzed period, there was a proportional reduction compared to the other regions. The Southeast region had the greatest reduction, from 52.69% (n = 6786) in 2006 to 45.34% (n = 7828) in 2015. In the South region, the rate of ALD admissions decreased from 19.4% (n = 2498) in 2006 to 18.64% (n = 3219) in 2015 (Table 1).

| Region | North | Northeast | Southeast | South | Midwest | Total | |

| 2006 | n | 404 | 2508 | 6786 | 2498 | 683 | 12879 |

| % | 3.14 | 19.47 | 52.69 | 19.40 | 5.30 | 100 | |

| 2007 | n | 420 | 2995 | 7008 | 2725 | 647 | 13795 |

| % | 3.04 | 21.71 | 50.8 | 19.75 | 4.70 | 100 | |

| 2008 | n | 389 | 2613 | 7085 | 3169 | 926 | 14182 |

| % | 2.74 | 18.43 | 49.96 | 22.35 | 6.52 | 100 | |

| 2009 | n | 503 | 2900 | 8284 | 3322 | 980 | 15989 |

| % | 3.14 | 18.14 | 51.81 | 20.78 | 6.13 | 100 | |

| 2010 | n | 618 | 3211 | 8952 | 3471 | 1142 | 17394 |

| % | 3.55 | 18.46 | 51.47 | 19.96 | 6.56 | 100 | |

| 2011 | n | 757 | 3245 | 8737 | 3131 | 1181 | 17051 |

| % | 4.44 | 19.03 | 51.24 | 18.36 | 6.93 | 100 | |

| 2012 | n | 774 | 3771 | 8181 | 3224 | 1088 | 17038 |

| % | 4.54 | 22.13 | 48.02 | 18.92 | 6.39 | 100 | |

| 2013 | n | 724 | 4223 | 7958 | 3279 | 1277 | 17461 |

| % | 4.15 | 24.18 | 45.58 | 18.78 | 7.31 | 100 | |

| 2014 | n | 871 | 3983 | 7644 | 3156 | 1383 | 17037 |

| % | 5.11 | 23.38 | 44.87 | 18.52 | 8.12 | 100 | |

| 2015 | n | 782 | 3936 | 7828 | 3219 | 1502 | 17267 |

| % | 4.53 | 22.79 | 45.34 | 18.64 | 8.70 | 100 | |

| Total | n | 6242 | 33385 | 78463 | 31194 | 10809 | 160093 |

| % | 3.90 | 20.85 | 49.01 | 19.49 | 6.75 | 100 | |

When the total number of ALD deaths between 2006 and 2015 was evaluated, there was an increase of 24.72% over the years, with 8429 deaths in 2006 and 10513 in 2015. While all regions had an increase of deaths, the Southeast and Northeast regions had the highest mortality in the country in 2015 with 39.47% (n = 4150) and 31.82% (n = 3345), respectively. The North region had the lowest proportion of deaths, corresponding to 4.25% (n = 447) of the total number in 2015 (Table 2).

| Region | North | Northeast | Southeast | South | Midwest | Total | |

| 2006 | n | 204 | 2260 | 3953 | 1494 | 518 | 8429 |

| % | 2.42 | 26.81 | 46.90 | 17.72 | 6.15 | 100 | |

| 2007 | n | 244 | 2487 | 3926 | 1686 | 542 | 8885 |

| % | 2.75 | 27.99 | 44.19 | 18.98 | 6.10 | 100 | |

| 2008 | n | 286 | 2627 | 4097 | 1745 | 639 | 9394 |

| % | 3.04 | 27.96 | 43.61 | 18.58 | 6.80 | 100 | |

| 2009 | n | 305 | 2676 | 4131 | 1596 | 610 | 9318 |

| % | 3.27 | 28.72 | 44.33 | 17.13 | 6.55 | 100 | |

| 2010 | n | 350 | 2829 | 4310 | 1769 | 660 | 9918 |

| % | 3.53 | 28.52 | 43.46 | 17.84 | 6.65 | 100 | |

| 2011 | n | 317 | 2991 | 4424 | 1838 | 741 | 10311 |

| % | 3.07 | 29.01 | 42.91 | 17.83 | 7.19 | 100 | |

| 2012 | n | 391 | 3133 | 4303 | 1716 | 834 | 10377 |

| % | 3.77 | 30.19 | 41.47 | 16.54 | 8.04 | 100 | |

| 2013 | n | 411 | 3169 | 4142 | 1800 | 950 | 10472 |

| % | 3.92 | 30.26 | 39.55 | 17.19 | 9.07 | 100 | |

| 2014 | n | 459 | 3215 | 4153 | 1746 | 880 | 10453 |

| % | 4.39 | 30.76 | 39.73 | 16.70 | 8.42 | 100 | |

| 2015 | n | 447 | 3345 | 4150 | 1646 | 925 | 10513 |

| % | 4.25 | 31.82 | 39.47 | 15.66 | 8.80 | 100 | |

| Total | n | 3414 | 28732 | 41589 | 17036 | 7299 | 98070 |

| % | 3.48 | 29.30 | 42.41 | 17.37 | 7.44 | 100 | |

When the number of hospitalizations and deaths due to ALD was analyzed according to age group, we found that the age group between 50 and 59 years had the highest proportion of both hospitalizations and deaths [28.94% (n = 46329) of the total hospital admissions (data not shown) and 29.43% (n = 28864) of all deaths (Table 3)], followed by the age range of 40 to 49 years [27.33% (n = 43751) of the total hospital admissions (data not shown) and 28.05% (n = 27509) of all deaths (Table 3)]. On the other hand, the subgroup over 80 years presented with the lowest proportion of hospitalizations and deaths, corresponding to 1.99% (n = 3184) (data not shown) of admissions and 2.18% of deaths (n = 2135) (Table 3). Men were more frequently hospitalized than women in all Brazilian regions (81.68% vs 18.32%) (Table 4). Males also presented with the highest proportions of deaths in all regions, ranging from 86.22% (n = 6293) in the Midwest to 89.70% (n = 15282) in the South region (Table 5).

| Region | Age group, in years | |||||||||||||||||

| < 29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | ≥ 80 | Missing data | Total | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| North | 109 | 3.19 | 467 | 13.68 | 865 | 25.34 | 876 | 25.66 | 604 | 17.69 | 326 | 9.55 | 145 | 4.25 | 22 | 0.64 | 3414 | 100 |

| Northeast | 997 | 3.47 | 4502 | 15.67 | 8119 | 28.26 | 7335 | 25.53 | 4604 | 16.02 | 2273 | 7.91 | 835 | 2.91 | 67 | 0.23 | 28732 | 100 |

| Southeast | 704 | 1.69 | 4725 | 11.36 | 11594 | 27.88 | 13273 | 31.91 | 7553 | 18.16 | 2897 | 6.97 | 729 | 1.75 | 114 | 0.27 | 41589 | 100 |

| South | 234 | 1.37 | 1624 | 9.53 | 4706 | 27.62 | 5345 | 31.37 | 3389 | 19.89 | 1412 | 8.29 | 307 | 1.80 | 19 | 0.11 | 17036 | 100 |

| Midwest | 186 | 2.55 | 1083 | 14.84 | 2225 | 30.48 | 2035 | 27.88 | 1156 | 15.84 | 460 | 6.30 | 119 | 1.63 | 35 | 0.48 | 7299 | 100 |

| Total | 2230 | 2.27 | 12401 | 12.65 | 27509 | 28.05 | 28864 | 29.43 | 17306 | 17.65 | 7368 | 7.51 | 2135 | 2.18 | 257 | 0.26 | 98070 | 100 |

| Region | Male | Female | Total | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| North | 4846 | 77.64 | 1396 | 22.36 | 6242 | 100 |

| Northeast | 26694 | 79.96 | 6691 | 20.04 | 33385 | 100 |

| Southeast | 64329 | 81.99 | 14134 | 18 | 78463 | 100 |

| South | 26308 | 84.34 | 4886 | 15.66 | 31194 | 100 |

| Midwest | 8590 | 79.47 | 2219 | 20.53 | 10809 | 100 |

| Total | 130767 | 81.68 | 29326 | 18.32 | 160093 | 100 |

| Region | Male | Female | Total | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| North | 3020 | 88.48 | 393 | 11.51 | 3413 | 100 |

| Northeast | 25260 | 87.92 | 3463 | 12.05 | 28723 | 100 |

| Southeast | 36273 | 87.22 | 5311 | 12.77 | 41584 | 100 |

| South | 15282 | 89.70 | 1753 | 10.29 | 17035 | 100 |

| Midwest | 6293 | 86.22 | 1005 | 13.77 | 7298 | 100 |

| Total | 86128 | 87.82 | 11925 | 12.16 | 98053 | 100 |

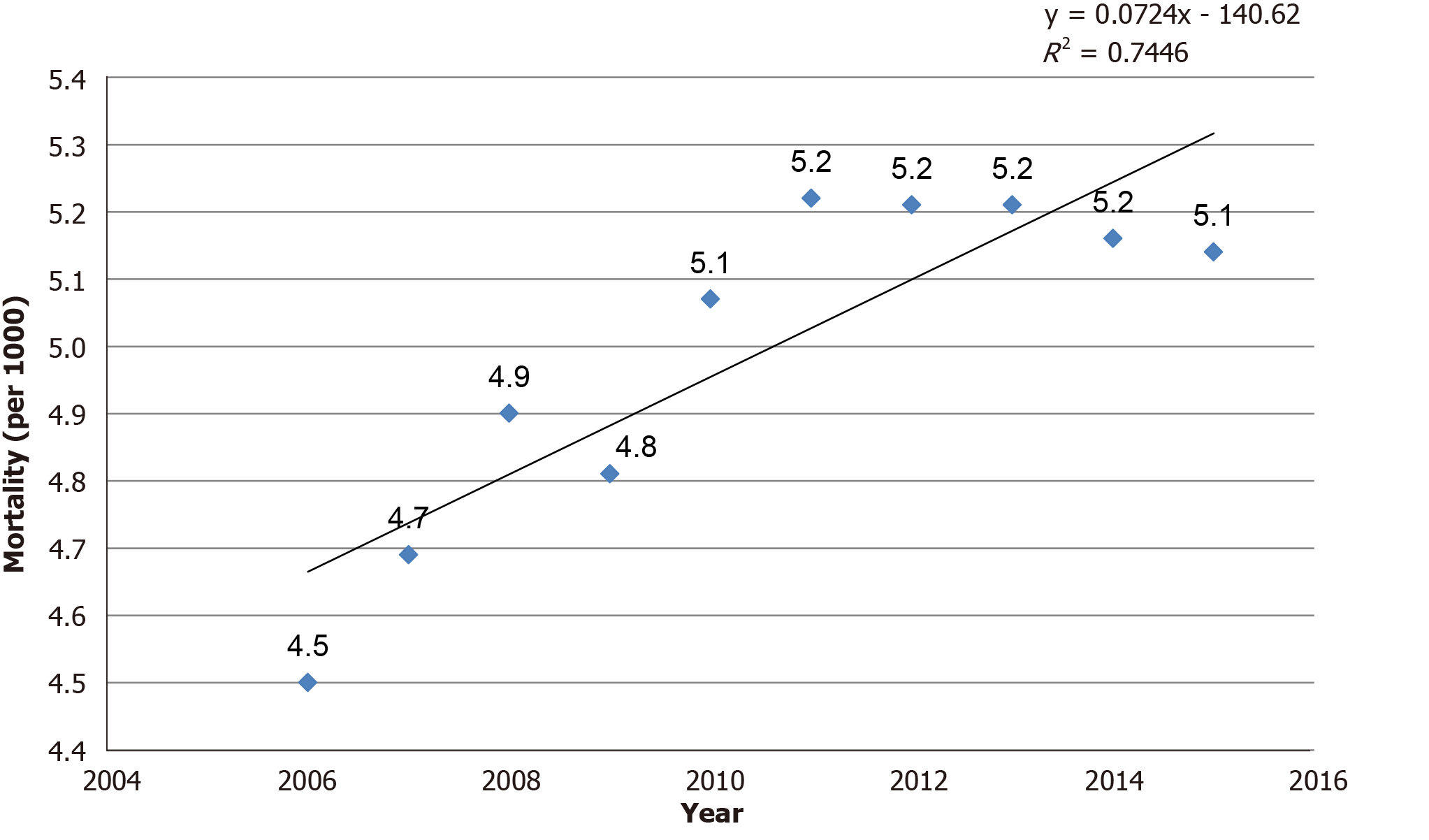

The mortality rate coefficients increased over the years in the North, Northeast, South and Midwest regions, while a lower coefficient was detected in the Southeast region. The highest mortality coefficients were observed in the Midwest (5.99 in 2015) and South (6.49 in 2011). The lowest coefficient in 2015 was found in the North region (2.56). Simple linear regression analysis indicated that the upward trend of this mortality was statistically significant (y = 0.072x– 140.62). The coefficient of determination was R² = 0.744 (Figure 2, Table 6). The mortality coefficient was highest in the age groups of 50 to 59 years, 60 to 69 years, and 70 to 79 years. The mortality coefficient for the ≤ 29 years old and ≥ 80 years or older age groups remained stable. When analyzing the mortality coefficients according to sex, men had the highest values throughout the study period, ranging from 7.99 to 9.26; women had the lowest values, ranging from 1.07 to 1.30 (data not shown).

| Region | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

| North | 1.35 | 1.59 | 1.83 | 1.91 | 2.16 | 1.92 | 2.34 | 2.42 | 2.66 | 2.56 |

| Northeast | 4.30 | 4.69 | 4.91 | 4.95 | 5.19 | 5.44 | 5.66 | 5.68 | 5.72 | 5.91 |

| Southeast | 4.98 | 4.90 | 5.06 | 5.06 | 5.23 | 5.32 | 5.14 | 4.90 | 4.88 | 4.84 |

| South | 5.51 | 6.16 | 6.32 | 5.73 | 6.30 | 6.49 | 6.01 | 6.25 | 6.02 | 5.63 |

| Midwest | 3.88 | 3.99 | 4.63 | 4.34 | 4.62 | 5.10 | 5.65 | 6.34 | 5.78 | 5.99 |

| Total | 4.50 | 4.69 | 4.90 | 4.81 | 5.07 | 5.22 | 5.21 | 5.21 | 5.16 | 5.14 |

Our study showed a burden of more than 150000 registered hospitalizations for ALD over 10 years. We also detected an increase in the total number of hospital admissions for ALD during the study period. We are unsure if this increase reflects an actual augmentation of the disease’s burden or an increase in the number of admitted patients. If it reflects the first situation, it would be interesting to speculate that alcohol consumption could be growing in Brazil and public health authorities should be alerted to consider undertaking measures to mitigate this problem and its consequences.

Notably, as expected, our study detected a sharp increase in the admission rate for ALD in the population over 30 years old, reaching its peak in the 40- and 59-year-old age group, the most afflicted age range. On the other hand, the elderly population appears to be less affected, probably because most patients with ALD will die or be transplanted earlier in the course of the illness or will stop drinking and improve.

As expected, the region with the highest proportion of hospitalizations during the study period was the Southeast because it concentrates the greatest population of the country. Nevertheless, a decrease in this proportion from 2012 to 2015 was observed. In other words, while there was an overall 34.07% increase in the total number of admissions over these 10 years, this rise was approximately 15% in the Southeast region. This might have occurred for one or more of the following reasons: An increase in the number of disease notifications of other regions, an improvement of the regional health care system of the Southeast region, or a decrease in the disease incidence in that particular area.

It is interesting to note that the North and Midwest regions have similar population sizes. However, the North region had the lowest absolute number of patients throughout the study period, corresponding to 3.9% of the total (n = 6242) compared to 6.75% (n = 10809) in the Midwest region. We are unsure if this difference is due to better disease reporting or a finer regional health care system in the Midwest or a lower disease incidence in the North.

The mortality rate was higher in the 40- and 59-year-old age groups as well. Therefore, it is interesting to speculate that excessive beverage ingestion starts during young adulthood, and this population should be educated regarding the hazards of the disease[5,11-13]. It is also interesting to mention that men accounted for the majority of the affected patients across all regions. Mortality coefficient analysis showed an increase of the death rates in the North, Northeast, South and Midwest regions, while there was a decrease in the Southeast region. The highest mortality coefficients were observed in the Midwest and Northeast. The mortality rate among males increased while it remained stable among females.

It is expected that men’s drinking habits are greater than women’s because culturally, in Brazil and possibly worldwide, women are not supposed to socially drink more than men. Nevertheless, our study still detected ALD in a reasonable number of females, and this issue should be addressed by public authorities.

Some countries have banned household alcohol production, increased taxation on factory-produced alcohol, specified the legal age of consumption of alcohol at 21 years of age, and identified and monitored one dry day a week on weekdays[14,15]. Meta-analyses and reviews have detected that a price increase for alcohol beverages was associated with a decrease in its consumption. It is estimated that a 10% price increase might be associated with a 5% reduction in consumption, on average[5,8,11,14-16].

Another possible action could be focused on marketing interventions and regulations. It has been reported that for each 10% increase in advertising expenditure, there is a 0.3% increase in adult alcohol consumption[7,11,17,18]. Therefore, the implementation of policies reinforcing explanations of the ill effects of alcohol the same way it is performed for smoking could be effective. The Brazilian government has conducted massive television broadcasts to clarify the potential consequences of smoking, including lung cancer and other types of malignant neoplasia. Additionally, the manufacturers are obliged to expose the outcomes of smoking as well during cigarette advertisements. Therefore, a similar procedure could be performed to educate the population about the potential hazards of excessive alcohol ingestion, including the development of ALD, alcoholic hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, and liver cancer.

It is important to be aware that this study was conducted using a government secondary database in the public domain which is fed by numerous health professionals in each region. Therefore, the accuracy of the provided information cannot be evaluated. Also, the database does not provide further details regarding the studied population. Therefore, we were unable to look in-depth if the reason for hospital admission was only due to ALD or other associated conditions might have influenced. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that usually the main reason for the hospital admission is inserted in the database.

In summary, our study has provided a landscape of the epidemiological profile of hospital admissions due to ALD in different regions of Brazil from 2006 to 2015, including the mortality rates and admissions according to age range. We detected a 34.07% increase in the total number of hospital admissions for ALD and a 24.72% increase in the total number of ALD deaths over these 10 years. Notably, the Brazilian population increased by only 10% during the same period. Therefore, this study signals the need to be alert to this liver illness and to possibly revisit policies related to alcohol marketing, sales, and consumption.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. Individuals with long-term significant alcohol consumption remain at risk for liver disease that may range from alcoholic steatohepatitis to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

It is important to know the epidemiology of ALD within a specific region/country to better understand which resources might be necessary to improve management. ALD might have been overlooked in recent years due to recent therapy advances in other Hepatology fields.

To describe the epidemiological profile of hospital admissions due to ALD in different regions of Brazil from 2006 to 2015, including the mortality rates and admissions according to age range.

This is a descriptive study that has evaluated aggregate data. Data from the five Brazilian geographic regions were used for the study.

There was a 34.07% increase in the total number of admissions over these 10 years, from 12879 in 2006 to 17267 in 2015 as well as a 24.72% increase in the total number of ALD deaths between 2006 and 2015. We found that the age group between 50 and 59 years had the highest proportion of both hospitalizations and deaths: 28.94% (n = 46329) of total hospital admissions and 29.43% (n = 28864) of all deaths. Men were more frequently hospitalized than women and had the highest proportions of deaths in all regions. Mortality coefficient rates increased over the years, and simple linear regression analysis indicated a statistically significant upward trend in this mortality (R² = 0.744).

Our study has provided a landscape of the epidemiological profile of public hospital admissions due to ALD in Brazil. We detected an increase in the total number of admissions and deaths due to ALD over 10 years.

This study signals the need to be alert to this liver illness and to possibly revisit policies related to alcohol marketing, sales, and consumption.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mesquita J, Surani SR, Zanetto A S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Bell G, Cremona A. Alcohol and death certification: a survey of current practice and attitudes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singal AK, Louvet A, Shah VH, Kamath PS. Grand Rounds: Alcoholic Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:534-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thursz M, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Moreno C, Spahr L, Sterneck M, Cortez-Pinto H. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69:154-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 84.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dash A, Figler RA, Sanyal AJ, Wamhoff BR. Drug-induced steatohepatitis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:193-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hazeldine S, Hydes T, Sheron N. Alcoholic liver disease - the extent of the problem and what you can do about it. Clin Med (Lond). 2015;15:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fazel Y, Koenig AB, Sayiner M, Goodman ZD, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1017-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Burton R, Henn C, Lavoie D, O'Connor R, Perkins C, Sweeney K, Greaves F, Ferguson B, Beynon C, Belloni A, Musto V, Marsden J, Sheron N. A rapid evidence review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: an English perspective. Lancet. 2017;389:1558-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pimpin L, Cortez-Pinto H, Negro F, Corbould E, Lazarus JV, Webber L, Sheron N; EASL HEPAHEALTH Steering Committee. Burden of liver disease in Europe: Epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J Hepatol. 2018;69:718-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 68.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ministry of Health. DATASUS 2018. Available from: http://www.datasus.gov.br. |

| 10. | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br. |

| 11. | Nelson JP, McNall AD. Alcohol prices, taxes, and alcohol-related harms: A critical review of natural experiments in alcohol policy for nine countries. Health Policy. 2016;120:264-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373:2234-2246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 660] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wangchuk P. Burden of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Bhutan Scenario. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2018;8:81-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Noel JK, Babor TF, Robaina K. Industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing: a systematic review of content and exposure research. Addiction. 2017;112 Suppl 1:28-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Österberg E, Lindeman M, Karlsson T. Changes in alcohol policies and public opinions in Finland 2003-2013. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sheron N, Chilcott F, Matthews L, Challoner B, Thomas M. Impact of minimum price per unit of alcohol on patients with liver disease in the UK. Clin Med (Lond). 2014;14:396-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2270-2278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Chattopadhyay SK, Toomey TL, Fielding JE; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:217-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |