Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.103360

Revised: December 26, 2024

Accepted: February 13, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 124 Days and 18.2 Hours

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a clinical syndrome characterized by a rapid deterioration in kidney function and has a significant impact on patient health and survival. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have the potential to enhance renal function by suppressing the expression of cell cycle inhibitors and reducing the expression of senescence markers and microRNAs via paracrine and endocrine mechanisms. MSC-derived exosomes can alleviate AKI symptoms by regulating DNA damage, apoptosis, and other related signaling pathways through the delivery of proteins, microRNAs, long-chain noncoding RNAs, and circular RNAs. This technique is both safe and effective. MSC-derived exosomes may have great application prospects in the treatment of AKI. Understanding the under

Core Tip: Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells are increasingly recognized for their small size, lack of cellular components, stability, enhanced biocompatibility, and reduced toxicity. In studies of experimental acute kidney injury, exosomes have shown great potential in terms of their safety and efficacy as well as their ability to modulate gene expression and transcription in recipient cells.

- Citation: Wang JJ, Zheng Y, Li YL, Xiao Y, Ren YY, Tian YQ. Emerging role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in the repair of acute kidney injury. World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(3): 103360

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i3/103360.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.103360

Acute kidney injury (AKI) covers a range of clinical conditions characterized by a sudden and prolonged decline in renal function. It is defined by an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 μmol/L) over a 48-h period or an increase in serum creatinine to at least 1.5 times the baseline, which is either known or presumed to have occurred within the preceding 7 days. Additionally, AKI may be indicated by a urine output of less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for a duration of 6 h[1,2]. AKI may present with oliguria (defined as urine output of less than 400 mL over 24 h or 17 mL/hour) or anuria (defined as urine output of less than 100 mL over 24 h).

Identified risk factors for the development of AKI include advanced age, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, a high percentage of total body surface area burned, an elevated abbreviated burn severity index score, inhalation injury, rhabdomyolysis, surgical intervention, a high Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, an increased Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, sepsis, mechanical ventilation, hypoalbuminemia, specific genetic polymorphisms, and drug-induced AKI[3-5]. AKI poses a significant threat to human health, with recent findings indicating that approximately 30% of patients exhibited preadmission renal dysfunction. The period prevalence of acute renal failure necessitating renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit was 5.0%-6.0%, with an overall hospital mortality rate of 60.3% (95% confidence interval: 58.0%-62.6%)[6].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are stromal cells with the ability for self-renewal and multidirectional differentiation. They can be isolated from various tissues, including adipose tissue, the umbilical cord, endometrial polyps, menstrual blood, and bone marrow[7,8]. MSCs possess the ability to differentiate into various cell lineages, which has significantly advanced the field of stem cell therapy and has become an innovative treatment method. As a key cellular component, exosomes can replicate the biological potential of MSCs. Compared to MSCs, exosomes secreted by MSCs offer sub

The pivotal factors contributing to AKI encompass ischemia, hypoxia, immunological reactions, and nephrotoxicity[12,13]. Inflammation is a significant supplementary aspect in AKI, orchestrating the progression to the extension phase of renal damage. The kidney, a highly complex organ, is vulnerable to numerous injuries due to its intricate structure, which includes tubules, glomeruli, interstitium, and intrarenal blood vessels. Consequently, kidney injury is classified into four main categories: Tubular; glomerular; interstitial; and vascular damage. The progress in contemporary renal treatment strategies includes two major approaches. One is to repair the damaged organ to restore its function, and the other is to replace it with cells, bioengineering devices, or engineered tissues. In the event of kidney injury, diverse cellular demise pathways manifest, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis[14-17]. These intricate mechanisms paradoxically act as protective shields for renal tissue against further insult. However, the kidney repair process, which is highly complex, is mainly controlled by paracrine communication within the microenvironment.

Transforming growth factor-β, a cornerstone cytokine, plays a critical role in tissue repair and fibrosis[18]. Its profibrotic signaling pathway converges at the activation of β-catenin. Remarkably, the β-catenin/Foxo interaction redirects transforming growth factor-β signaling away from fibrosis towards physiological epithelial healing. In the intricate process of renal injury repair, a wide range of cytokines and growth factors play crucial roles. Among these, insulin-like growth factor-1[19], stromal cell-derived factor-1[20], vascular endothelial growth factor[21], and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[22] are all intricately involved. These potent molecules work together to create a conducive environment for kidney function restoration, tubular repair, and regeneration, thereby ensuring a smoother process. By enhancing cellular proliferation, promoting angiogenesis, and facilitating the migration of reparative cells, they contribute significantly to the overall recovery from kidney injury[23]. Recently, the therapeutic potential of MSCs and extracellular vesicles (EVs) has garnered significant attention among researchers exploring avenues to combat kidney diseases[24]. These innovative therapeutic approaches offer the promise of revolutionizing the treatment of kidney diseases.

AKI is now widely recognized as an expansive clinical syndrome with a diverse array of causative factors. This expansive syndrome encompasses acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis, prerenal azotemia, acute glomerular, vasculitic renal disorders, and acute postrenal obstructive nephropathy, all of which contribute to its complex nature[25]. Based on the anatomical site of injury, AKI can be neatly categorized into three distinct groups, including prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal. Prerenal AKI stems from hypoperfusion of the kidneys, a condition colloquially known as prerenal azotemia. This reduction in glomerular filtration rate arises from diminished blood flow to the kidneys, occurring in the absence of any discernible parenchymal damage. Intrinsic AKI, the most prevalent form among these categories, encompasses a broad spectrum of processes that inflict injury upon glomerular, interstitial, tubular, or endothelial cells within the kidney itself[26]. These insults can be multifarious, ranging from inflammatory processes to direct cellular damage. Lastly, postrenal AKI arises as a consequence of either partial or complete obstruction within the venous outflow or urinary tract, impeding the normal flow of fluids and waste products. To provide a comprehensive understanding, the underlying reasons for each category of AKI have been meticulously summarized in the Table 1, offering a detailed glimpse into the intricacies of this complex clinical syndrome.

| Causes of AKI | Specific causes |

| Prerenal | Renal hypoperfusion, such as acute bleeding or diarrhea, dehydration, shock |

| Intrinsic | Renal ischemia, drug nephrotoxicity, glomerulonephritis, infection, ischemia-reperfusion injury, different group blood transfusion, vasculitis, etc. |

| Postrenal | Lithiasis, tumor, prostatomegaly |

In recent years, the EVs that are liberated by MSCs have emerged as the epicenter of intense scientific inquiry. This shift in focus underscores the growing recognition of the pivotal role that EVs play in mediating a myriad of biological processes. Emerging evidence have definitively demonstrated that MSCs and their exosomes have therapeutic effects on AKI. This section elaborates on the origin, function, and characteristics of MSCs and EVs and compares the therapeutic effects of MSCs and EVs from different sources on AKI.

MSCs, which are also known as mesenchymal stromal cells, were first discovered within the bone marrow stroma of pigs in the 1960s[27]. MSCs are paramount in mitigating the harmful effects and promoting the body’s natural recovery mechanisms in organ injury diseases[28]. MSCs are characterized by a distinct set of surface molecules, including CD73, CD90, and CD105 as the prominent and key identifiers. Conversely, they are devoid of the expression of certain surface molecules that are characteristic of other cell types, including CD34, CD45, human leukocyte antigen-D related, CD14, CD11b, CD79a, and CD19[29,30]. MSCs possess an extraordinary plasticity including a high self-renewal capacity, multilineage differentiation potential, and immunomodulatory properties[31].

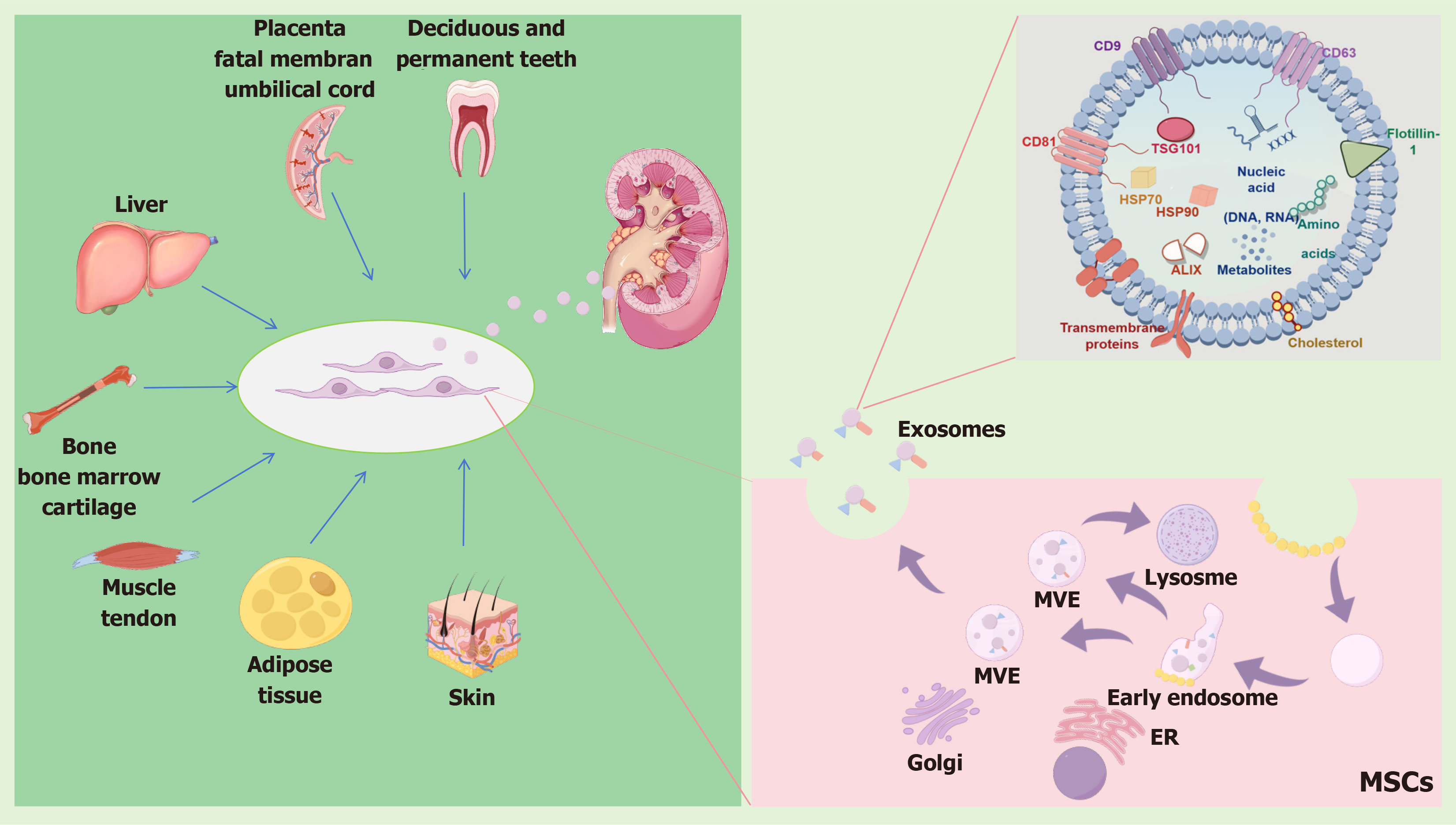

A diverse array of human sources has been harnessed for the generation of differentiated MSC populations, spanning across various tissues and organs. These include but are not limited to: bone and bone marrow, which offer a rich repository[32-36]; cartilage, noted for its unique regenerative potential[37]; tendon, with its inherent strength and flexibility[38]; muscle, for its dynamic properties[39]; liver, as a vital metabolic hub[40]; adipose tissue and skin, which are abundant and accessible sources[41-43]; placenta and fetal membrane, representing early developmental stages[44]; the umbilical cord, serving as a bridge connecting mother and child; and even deciduous and permanent teeth[45], highlighting the vast regenerative capabilities embedded within our bodies. This broad spectrum of sources underscores the remarkable versatility of MSCs and their potential for use in diverse therapeutic applications, where each source may confer unique advantages depending on the specific requirements of the targeted tissue or condition. Historically, bone marrow has been the primary and well-established source of MSCs in human research and clinical applications[46]. However, umbilical cord tissue has proven to be a rich source of MSCs, and it is characterized by its pristine stemness, making it a prominent alternative[34].

Many studies have illuminated the changes in MSC characteristics and functionalities across various settings, including cell phenotype, proliferation, differentiation, migration, apoptosis, and factor secretion. Furthermore, their low immunogenicity coupled with their trophic properties underscores their remarkable therapeutic potential[47,48]. These distinctive properties of MSCs endow them with immense potential for the development of innovative MSC-based or MSC-derived therapeutic interventions. MSCs have a remarkable ability to enhance cell viability and proliferation, which is crucial for tissue repair and regeneration.

Studies have shown that MSCs can promote the proliferation of muscle cells and enhance their differentiation. They can also improve the contractile ability of muscle cells. Additionally, the effect of MSCs on angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation is significant, particularly under hypoxic conditions, which further supports their role in tissue repair. Moreover, they effectively inhibit cell apoptosis, thereby preserving vital cellular functions in the affected tissues. In some cases, MSCs exhibit the capacity to modulate immune responses, orchestrating a healing environment that aids in the restoration of injured and diseased tissues[28,49-53]. The broad therapeutic potential underscores the crucial role MSCs could play in advancing the realm of regenerative medicine.

AKI likely leads to cellular senescence, which may be closely related to mechanisms such as cell cycle arrest and downregulation of Klotho protein expression[54]. Notably, human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (HucMSCs) are more effective than bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMMSCs) or adult adipose-derived MSCs (ADMSCs) in reducing the expression of cell cycle inhibitors[55]. In an experimental study on ischemia-reperfusion injury, the use of HucMSCs has recently been reported to improve renal function and downregulate the expression of senescence markers (β-galactosidase, p21Waf1/Cip1, and p16INK4a) and microRNAs (miRNA) (miR-29a and miR-34a) that are upregulated. Compared to adult ADMSCs, younger (postnatal) cells appear to be more effective in treating AKI[56]. It was found that MSCs derived from Wharton’s jelly have a superior ability to increase Klotho protein levels compared to ADMSCs, thereby more effectively protecting tissues from the effects of aging. The younger the cells, the more factors associated with the youth they possess. By comparing cells collected from umbilical cords, newborns 4 days after birth, mothers, and adult volunteers, the results showed that the levels of soluble Klotho in cells from umbilical cords were significantly higher. Additionally, HucMSCs exhibited a higher expression of Klotho than ADMSCs[57,58].

Moreover, MSCs release EVs, which serve as vehicles for delivering crucial cargoes, enhancing their ability to promote tissue regeneration and healing[59,60]. The established classification framework for electric vehicles, metaphorically applied to membrane structures, meticulously segregates them into three distinct categories: Exosomes; ectosomes (herein designated as microvesicles, or MVs for brevity); and apoptotic bodies[61].

Exosomes, minute vesicles exquisitely defined by their diameter spanning 30-100 nm and a density meticulously calibrated within the range of 1.13-1.19 g/cm2, have been meticulously identified as the product of a sophisticated process involving the fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane[62]. This fusion event triggers their liberation into the extracellular milieu, indicating their pivotal role in intercellular communication and the dynamic exchange of biological molecules. EVs can be definitively discerned through the presence of distinctive markers that serve as hallmarks of their endocytic derivation, encompassing CD63, CD81, and CD9, among others[63].

MVs, whose dimensions range from 100-1000 nm, are elegantly expelled from the plasma membrane via a direct, outward budding process[64]. However, a definitive marker for identifying MVs remains elusive. Apoptotic bodies, arising as a consequence of cellular fragmentation during the terminal stages of apoptosis, are released into the surrounding environment. These bodies exhibit a remarkable range in their diameters, spanning from 1000-5000 nm[64].

EVs are nanoscale vehicles that encapsulate a wide range of bioactive molecules, including essential proteins such as cytokines, receptors, and their corresponding ligands, as well as a complex array of nucleic acids like DNA, mRNA, miRNA, and the elusive long-chain noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). These vesicles play a crucial role in intercellular communication and have been extensively studied for their potential in drug delivery, leveraging their natural biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity, and non-immunogenic properties. Additionally, they carry sugars and lipids, forming a comprehensive repertoire that underscores their intricate biological makeup and functional potential[65]. The intricate interplay between MSCs and their EV cargo, which encompasses a treasure trove of bioactive molecules, has sparked a renaissance in the field, fostering novel insights into regenerative medicine, immunology, and intercellular communication.

The initial proof of the advantageous impact of EVs released by BMMSCs was provided by Bruno et al[66] in 2009, using a model of AKI caused by glycerol injection in SCID mice. The impact of EVs was found to be comparable to that of the original MSCs, suggesting that EVs could potentially replace cell therapy. Furthermore, EVs isolated from liver-resident MSCs were administered intravenously in an AKI model induced by glycerol, resulting in improved renal function and morphology[67]. In the ischemia/reperfusion injury model, EVs released by BMMSCs have proven to be effective[68]. The use of exosomes released by fetal tissue-derived MSCs, such as umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs and Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs, has also yielded similarly positive effects, despite their different mechanisms of action[69-71].

Through the induction of rat HGF and the transfer of human HGF, EVs secreted by umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs accelerated the dedifferentiation and growth of renal tubular cells. Conversely, EVs released by Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs have the ability to stimulate cell proliferation through mitochondrial protective effects and to reduce inflammation and apoptosis[69,70]. Furthermore, it was found that exosomes derived from ADMSCs and those from BMMSCs can reduce oxidative stress and inflammation and have a significant impact on the autophagy levels of kidney tissue. Additionally, compared to exosomes derived from BMMSCs, exosomes derived from ADMSCs are more significant in improving kidney function and structure, combating lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced AKI by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation[72]. In summary, we can see that EVs derived from various MSC sources demonstrate potent therapeutic effects in all models of AKI. The mechanism of action appears to be multifaceted, promoting proliferation and survival of resident cells while also limiting inflammation, oxidative stress, and angiogenesis.

A multitude of exhaustive studies have definitively demonstrated that MSCs and their exosomes can significantly alleviate the severity of AKI. However, the complex mechanisms responsible for these therapeutic effects exhibit considerable variation between MSCs and their exosomes. Yun and Lee[73] delved into the promising potential and therapeutic efficacy of MSC-based treatments, specifically addressing their application in the management of both acute and chronic kidney diseases. They comprehensively outlined how the mechanisms of MSCs in fostering renal recovery, in optimizing the cellular microenvironment, and in regulating inflammatory responses are intricately linked to their intricate interactions within the compromised kidney milieu. These multifaceted interactions are believed to underlie the therapeutic potential of MSCs, as they not only promote tissue regeneration but also modulate the surrounding environment to facilitate a more conducive healing process. In this comprehensive review, we have meticulously synthesized the most recent advancements in elucidating the intricate mechanisms underlying the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived exosomes for the treatment of AKI.

Proteins are important components of exosomes and play a crucial role in various cellular processes. The traditional perspective holds that the primary methods of repair by MSCs involve paracrine and endocrine effects, including their anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic influences. However, Wang et al[74] demonstrated that exosomes transported by HucMSCs, specifically containing the protein 14-3-3ζ, can potentially enhance autophagic activity to protect HK-2 cells from cisplatin-induced injury. This suggests a more complex and multifaceted role of exosomes in cellular repair processes than previously thought. The protein 14-3-3ζ is a crucial functional molecule that plays a role in numerous vital biological processes.

Recently, 14-3-3ζ was shown to have protective effects against cisplatin-induced AKI by enhancing mitochondrial function and restoring the balance between cellular proliferation and apoptosis through the facilitation of β-catenin nuclear translocation[75]. Jia et al[76] also conclusively demonstrated that the 14-3-3ζ protein, encapsulated within exosomes derived from HucMSCs, engages in a pivotal interaction with autophagy-related protein 16 L, thereby triggering the activation of autophagy. This intricate mechanism serves as a potent safeguard against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, offering a novel therapeutic avenue for mitigating the adverse renal effects associated with this chemo

The intricate interplay between cellular signaling pathways and the promising potential of exosome-mediated therapies in protecting against chemotherapy-induced organ damage is supported by recent studies, such as the one highlighting the protective role of exosomes in acute organ injuries, including the heart and kidneys. Moreover, Yin et al[77] uncovered a pivotal role of protein 14-3-3ζ in diabetic kidney disease. Notably, this protein could effectively promote the cytoplasmic sequestration of Yes-associated protein 1, thereby preventing its nuclear translocation, and it could augment the level of autophagy in the cytoplasm. These studies have shown that the delivery of 14-3-3ζ by MSC-derived exosomes could be a critical mechanism through which MSCs exert their therapeutic effects on AKI. A different study found that the use of ADMSC therapy could enhance the expression of tubular Sry-related HMG box 9, actively stimulate tubular regeneration, and effectively reduce the severity of AKI[78].

MiRNAs are a complex class of endogenous non-coding RNAs, serving as crucial genetic regulators. Recently, numerous studies have been dedicated to examining the delivery of miRNAs via exosomes secreted by MSCs in AKI. Cao et al[79] investigated the role of miR-125b-5p, a molecule prominently abundant in HucMSC-derived exosomes, in suppressing p53 to facilitate tubular repair during ischemic AKI. This downregulation not only elicited a stimulatory effect on CDK1 and cyclin B1, thereby alleviating the G2/M cell cycle arrest, but also meticulously orchestrated the balance between Bcl-2 and Bax, two key regulators of apoptosis. This discovery offered important insights into the intricate mechanisms underlying renal recovery after injury[79].

Wang et al[80] demonstrated that the presence of miRNA let-7b-5p in MSC-derived exosomes effectively mitigated tubular epithelial cell apoptosis by inhibiting p53 expression. This process subsequently reduced DNA damage and apoptosis pathway activity, highlighting the potential role of miRNAs in promoting cell survival through MSC-derived exosomes[80].

Furthermore, HucMSC-derived exosomes may be a promising therapeutic agent capable of precisely modulating necroptosis through the complex targeting of miR-874-3p to the receptor-interacting protein kinase 1/phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 pathway. This complex interaction not only alleviates renal tubular epithelial cell injury but also promotes robust repair mechanisms, thus presenting a potential therapeutic strategy[81]. HucMSCs have also been found to exhibit a remarkable ability in suppressing interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase 1 expression, a key regulatory factor, by significantly upregulating the level of miR-146b. This complex molecular interplay subsequently leads to the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activity, a key mediator of inflammatory cascades. Consequently, sepsis-associated AKI is effectively alleviated, and the survival rates of mice with sepsis are improved[82].

Another study showed that miR-199a-3p was notably abundant in exosomes derived from BMMSCs. These exosomes reduced the expression of semaphorin 3A and activated both the protein kinase B and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase pathways. Consequently, they play a protective role in mitigating the effects of hypoxia/reoxygenation injury[83]. Excitingly, it has been observed that exosomes derived from miR-1-184 agomir-treated MSCs effectively counteract cisplatin-induced suppression of cell growth by mitigating apoptosis. Simultaneously, these treated MSCs have demonstrated a significant induction of G1 phase arrest in HK-2 cells through the regulation of Forkhead box protein O 4, p27 Kip1, and CDK2 while also mitigating inflammatory responses[84].

Zhang et al[85] found that human urine-derived stem cells harbor an abundance of miR-216a-5p, which significantly downregulates the expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog and orchestrates a cascade of events, ultimately regulating cell apoptosis through the intricate protein kinase B signaling pathway[85]. A study revealed that exosomes derived from ADMSCs, carrying miR-342-5p, can ameliorate sepsis-associated AKI. Specifically, this research demon

The therapeutic value of miRNAs in MSCs-derived exosome lies in tissue recovery, renal protection and regeneration, modulation of inflammatory responses, and mitigation of the devastating consequences of sepsis, among others. This holds great significance and prospect for the treatment of clinical kidney injury-related diseases.

LncRNAs represent a class of RNA molecules that, contrary to their protein-coding counterparts, do not directly encode for proteins. Instead, they play pivotal roles in modulating gene expression across diverse levels and through intricate mechanisms. These versatile molecules orchestrate the intricate dance of gene regulation, influencing not only the maturation of mRNA transcripts but also the intricate architecture of chromatin. Furthermore, lncRNAs engage in competitive interactions with miRNAs, vying for binding sites on endogenous RNAs, thereby adding another layer of complexity to the intricate web of gene regulatory networks[87].

The delivery of lncRNA via exosomes derived from MSCs plays a pivotal role in safeguarding AKI. A study has shown that exosomes secreted by HucMSCs are rich in lncRNA TUG1. This lncRNA has been found to interact with RNA-binding proteins, such as serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1, which is crucial for the regulation of mRNA stability, as seen in the context of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 mRNA. Consequently, it curtails ferroptosis in HK-2 cells subjected to conditions of hypoxia followed by reoxygenation. A comparable phenomenon is also observed in cases of ischemia/reperfusion-induced AKI in mice[88]. The lncRNA delivery by MSCs through exosomes indicates a profound mechanism in mitigating kidney damage, pointing to potential therapeutic strategies in the future.

Circular RNAs constitute a distinct category of RNA molecules that are formed through a covalent bond due to the back-splicing of linear RNA sequences. Specifically, circVMA21 plays a pivotal role as a regulator in sepsis-associated AKI[89]. ADMSCs protected LPS-induced AKI in mice by increasing circVMA21 expression and decreasing miR-16-5p expression, which provided a potential molecular target for treating sepsis-related AKI. ADMSCs were found to offer protection against LPS-induced AKI in mice. The protective effect against AKI was achieved by enhancing the expression of circVMA21 and simultaneously suppressing the expression of miR-16-5p. The modulation of circVMA21 and miR-16-5p expression may serve as a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of sepsis-associated AKI, providing hope for patients afflicted with this condition.

Another notable discovery reveals that circular RNA circ DENND4C, when delivered via exosomes secreted from HucMSCs, possesses the capability to inhibit pyroptosis and effectively alleviate ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI[90]. In this context, we have comprehensively summarized the experimental findings pertaining to the molecular cargoes transmitted by MSC-derived exosomes (Figure 1, Table 2), which have been shown to significantly improve functional recovery in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage and hold immense potential for future clinical applications.

| Molecules | Source | AKI types | Conditions | Ref. | |

| Protein | 14-3-3ζ | HucMSC | Cisplatin-induced | Upregulating autophagic level | [74] |

| HucMSC | Cisplatin-induced | Interacting with ATG16 L to activate autophagy | [75] | ||

| HucMSC | Diabetic kidney disease | Promoting YAP cytoplasmic retention instead of entering the nucleus, enhancing autophagy in the cytoplasm | [76] | ||

| Sox9 | ADMSC | Ischemia/reperfusion | Upregulating Sox9 and promoting tubular regeneration | [78] | |

| MiRNA | MiR-125b-5p | HucMSC | Ischemia/reperfusion | Repressing p53, upregulating CDK1 and cyclin B1 to rescue G2/M arrest, and inhibiting tubular epithelial cell apoptosis | [79] |

| let-7b-5p | HBMMSC | Cisplatin-induced | Inhibiting P53 and reducing DNA damage and apoptosis | [80] | |

| MiR-874-3p | HucMSC | Cisplatin-induced | Targeting RIPK1/PGAM5 pathway | [81] | |

| MiR-146b | HucMSC | Sepsis-associated | Upregulating miR-146b levels and reducing IRAK1 expression resulting in inhibition of NF-κB activity | [82] | |

| MiR-199a-3p | HBMMSC | Hypoxia/reoxygenation injury | Decreasing Sema3A and activating the AKT and ERK pathways | [83] | |

| MiR-1184 | HucMSC | Cisplatin-induced | Inducing G1 phase arrest in HK-2 cells by regulating FOXO4, p27 Kip1, and CDK2. Inhibiting cisplatin-induced inflammatory responses | [84] | |

| MiR-216a-5p | USC | Ischemia/reperfusion | Targeting PTEN and regulating cell apoptosis through the AKT pathway | [85] | |

| MiR-342-5p | ADMSC | Sepsis-related | Inhibiting TLR9, thereby promoting autophagy, mitigating inflammation, and reducing kidney damage | [86] | |

| LncRNA | LncRNA TUG1 | HucMSC | Ischemia/reperfusion | Interacting with SRSF1 to regulate ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis | [88] |

| CircRNA | CircVMA21 | ADMSC | Sepsis-related | Increasing circVMA21 expression and decreasing miR-16-5p expression | [89] |

| Circ DENND4C | USC | Ischemia/reperfusion | Inhibiting pyroptosis | [90] | |

Despite ongoing research efforts, no effective treatment options for AKI have been discovered thus far, emphasizing the need for heightened awareness and proactive measures to combat this menace[91]. In recent years, research on biological therapy has been a key focus, particularly for a new star in this field: MSCs[92]. The diversity and pluripotency of MSCs make them promising candidates for developing innovative clinical applications. Cellular therapy encompasses a diverse array of mechanisms, intricately woven to address various physiological challenges. These mechanisms not only alleviate inflammation but also exert immunomodulatory effects, delicately modulating the response of the immune system. Furthermore, they demonstrate antiapoptotic properties, safeguarding cells from premature death and fostering their survival. In addition, they combat oxidative stress, mitigating the harmful effects of reactive oxygen species[80,91,93-95].

Although numerous studies have consistently shown the safety and efficacy of MSCs therapy, potential hidden safety concerns that necessitate further attention may remain[96-98]. Moreover, MSC-derived exosomes have shown significant promise in experimental AKI, not only for their safety and efficacy but also for their ability to modulate gene expression and transcription in recipient cells, which could have significant implications on cellular function and the overall therapeutic outcome. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct comprehensive research on the long-term effects of MSC-derived exosomes in order to assess their efficacy and safety profile, which should encompass a variety of areas, including the identification of potential side effects, evaluation of dose-response relationships, and examination of the interactions between exosomes and the recipient’s immune system. In summary, MSC-derived exosomes have demon

| 1. | Kellum JA, Lameire N; KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1192] [Cited by in RCA: 1852] [Article Influence: 154.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pickkers P, Darmon M, Hoste E, Joannidis M, Legrand M, Ostermann M, Prowle JR, Schneider A, Schetz M. Acute kidney injury in the critically ill: an updated review on pathophysiology and management. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:835-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim JY, Yee J, Yoon HY, Han JM, Gwak HS. Risk factors for vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3977-3989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Varrier M, Ostermann M. Novel risk factors for acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:560-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rey A, Gras-Champel V, Choukroun G, Masmoudi K, Liabeuf S. Risk factors for and characteristics of community- and hospital-acquired drug-induced acute kidney injuries. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2022;36:750-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, Gibney N, Tolwani A, Ronco C; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2897] [Cited by in RCA: 2921] [Article Influence: 146.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ding DC, Shyu WC, Lin SZ. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:5-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 584] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Ghadban S, Bunnell BA. Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells: Immunomodulatory Effects and Therapeutic Potential. Physiology (Bethesda). 2020;35:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lotfy A, AboQuella NM, Wang H. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang S, Guo L, Ge J, Yu L, Cai T, Tian R, Jiang Y, Zhao RCh, Wu Y. Excess Integrins Cause Lung Entrapment of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:3315-3326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang J, Cao H, Cui B, Ma X, Gao L, Yu C, Shen F, Yang X, Liu N, Qiu A, Cai G, Zhuang S. Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Ameliorate Ischemia/Reperfusion Induced Acute Kidney Injury in a Porcine Model. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:899869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Basile DP, Anderson MD, Sutton TA. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:1303-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 684] [Cited by in RCA: 774] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Molitoris BA, Sandoval R, Sutton TA. Endothelial injury and dysfunction in ischemic acute renal failure. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S235-S240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li N, Lin G, Zhang H, Sun J, Gui M, Liu Y, Li W, Zhan Z, Li Y, Pan S, Liu J, Tang J. Lyn attenuates sepsis-associated acute kidney injury by inhibition of phospho-STAT3 and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;211:115523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang F, Wang JN, He XY, Suo XG, Li C, Ni WJ, Cai YT, He Y, Fang XY, Dong YH, Xing T, Yang YR, Zhang F, Zhong X, Zang HM, Liu MM, Li J, Meng XM, Jin J. Stratifin promotes renal dysfunction in ischemic and nephrotoxic AKI mouse models via enhancing RIPK3-mediated necroptosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:330-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang Y, Zhang H, Chen Q, Jiao F, Shi C, Pei M, Lv J, Zhang H, Wang L, Gong Z. TNF-α/HMGB1 inflammation signalling pathway regulates pyroptosis during liver failure and acute kidney injury. Cell Prolif. 2020;53:e12829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sun X, Huang N, Li P, Dong X, Yang J, Zhang X, Zong WX, Gao S, Xin H. TRIM21 ubiquitylates GPX4 and promotes ferroptosis to aggravate ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Life Sci. 2023;321:121608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rao P, Qiao X, Hua W, Hu M, Tahan M, Chen T, Yu H, Ren X, Cao Q, Wang Y, Yang Y, Wang YM, Lee VW, Alexander SI, Harris DC, Zheng G. Promotion of β-Catenin/Forkhead Box Protein O Signaling Mediates Epithelial Repair in Kidney Injury. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:993-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Imberti B, Morigi M, Tomasoni S, Rota C, Corna D, Longaretti L, Rottoli D, Valsecchi F, Benigni A, Wang J, Abbate M, Zoja C, Remuzzi G. Insulin-like growth factor-1 sustains stem cell mediated renal repair. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2921-2928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sun Z, Li X, Zheng X, Cao P, Yu B, Wang W. Stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXC chemokine receptor 4 axis in injury repair and renal transplantation. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:5426-5440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yuan L, Wu MJ, Sun HY, Xiong J, Zhang Y, Liu CY, Fu LL, Liu DM, Liu HQ, Mei CL. VEGF-modified human embryonic mesenchymal stem cell implantation enhances protection against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F207-F218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu Y. Hepatocyte growth factor in kidney fibrosis: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lameire N. The pathophysiology of acute renal failure. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:197-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang Y, Yang L. Mesenchymal stem cells and extracellular vesicles in therapy against kidney diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P; Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204-R212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4448] [Cited by in RCA: 4702] [Article Influence: 223.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Molitoris BA. Low-Flow Acute Kidney Injury: The Pathophysiology of Prerenal Azotemia, Abdominal Compartment Syndrome, and Obstructive Uropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:1039-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3:393-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 949] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in RCA: 2700] [Article Influence: 168.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gong P, Zhang W, He Y, Wang J, Li S, Chen S, Ye Q, Li M. Classification and Characteristics of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Its Potential Therapeutic Mechanisms and Applications against Ischemic Stroke. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:2602871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mushahary D, Spittler A, Kasper C, Weber V, Charwat V. Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cytometry A. 2018;93:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Min SY, Desai A, Yang Z, Sharma A, DeSouza T, Genga RMJ, Kucukural A, Lifshitz LM, Nielsen S, Scheele C, Maehr R, Garber M, Corvera S. Diverse repertoire of human adipocyte subtypes develops from transcriptionally distinct mesenchymal progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:17970-17979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hou T, Xu J, Wu X, Xie Z, Luo F, Zhang Z, Zeng L. Umbilical cord Wharton's Jelly: a new potential cell source of mesenchymal stromal cells for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2325-2334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fekete N, Rojewski MT, Fürst D, Kreja L, Ignatius A, Dausend J, Schrezenmeier H. GMP-compliant isolation and large-scale expansion of bone marrow-derived MSC. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Voskamp C, Koevoet WJLM, Somoza RA, Caplan AI, Lefebvre V, van Osch GJVM, Narcisi R. Enhanced Chondrogenic Capacity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells After TNFα Pre-treatment. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ooi YY, Rahmat Z, Jose S, Ramasamy R, Vidyadaran S. Immunophenotype and differentiation capacity of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from CBA/Ca, ICR and Balb/c mice. World J Stem Cells. 2013;5:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Svensson S, Palmer M, Svensson J, Johansson A, Engqvist H, Omar O, Thomsen P. Monocytes and pyrophosphate promote mesenchymal stem cell viability and early osteogenic differentiation. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2022;33:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sandrasaigaran P, Algraittee SJR, Ahmad AR, Vidyadaran S, Ramasamy R. Characterisation and immunosuppressive activity of human cartilage-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotechnology. 2018;70:1037-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Al-Ani MKh, Xu K, Sun Y, Pan L, Xu Z, Yang L. Study of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal and Tendon-Derived Stem Cells Transplantation on the Regenerating Effect of Achilles Tendon Ruptures in Rats. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:984146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ćuti T, Antunović M, Marijanović I, Ivković A, Vukasović A, Matić I, Pećina M, Hudetz D. Capacity of muscle derived stem cells and pericytes to promote tendon graft integration and ligamentization following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1189-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Weiss MC, Strick-Marchand H. Isolation and characterization of mouse hepatic stem cells in vitro. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:313-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yang XF, He X, He J, Zhang LH, Su XJ, Dong ZY, Xu YJ, Li Y, Li YL. High efficient isolation and systematic identification of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Sci. 2011;18:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ciuffreda MC, Malpasso G, Musarò P, Turco V, Gnecchi M. Protocols for in vitro Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Osteogenic, Chondrogenic and Adipogenic Lineages. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1416:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Danisovic L, Varga I, Polák S, Ulicná M, Hlavacková L, Böhmer D, Vojtassák J. Comparison of in vitro chondrogenic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2009;28:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Raynaud CM, Maleki M, Lis R, Ahmed B, Al-Azwani I, Malek J, Safadi FF, Rafii A. Comprehensive characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human placenta and fetal membrane and their response to osteoactivin stimulation. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:658356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Anil S, Thomas NG, Chalisserry EP, Dalvi YB, Ramadoss R, Vellappally S. Isolation, Culture, and Characterization of Dental Pulp Stem Cells from Human Deciduous and Permanent Teeth. J Vis Exp. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15372] [Cited by in RCA: 15201] [Article Influence: 584.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Spees JL, Lee RH, Gregory CA. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 598] [Article Influence: 66.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kimbrel EA, Lanza R. Next-generation stem cells - ushering in a new era of cell-based therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:463-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Li L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Yu B, Xu Y, Guan Z. Paracrine action mediate the antifibrotic effect of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of global heart failure. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:725-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Dexter TM, Spooncer E, Toksoz D, Lajtha LG. The role of cells and their products in the regulation of in vitro stem cell proliferation and granulocyte development. J Supramol Struct. 1980;13:513-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringdén O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1048] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3271] [Cited by in RCA: 3279] [Article Influence: 156.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Liu M, He J, Zheng S, Zhang K, Ouyang Y, Zhang Y, Li C, Wu D. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate acute liver failure by inhibiting apoptosis, inflammation and pyroptosis. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:1615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Andrade L, Rodrigues CE, Gomes SA, Noronha IL. Acute Kidney Injury as a Condition of Renal Senescence. Cell Transplant. 2018;27:739-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Jin HJ, Bae YK, Kim M, Kwon SJ, Jeon HB, Choi SJ, Kim SW, Yang YS, Oh W, Chang JW. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood as sources of cell therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17986-18001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rodrigues CE, Capcha JM, de Bragança AC, Sanches TR, Gouveia PQ, de Oliveira PA, Malheiros DM, Volpini RA, Santinho MA, Santana BA, Calado RD, Noronha IL, Andrade L. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells protect against premature renal senescence resulting from oxidative stress in rats with acute kidney injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Yang HC, Rossini M, Ma LJ, Zuo Y, Ma J, Fogo AB. Cells derived from young bone marrow alleviate renal aging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2028-2036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Wagers AJ, Girma ER, Weissman IL, Rando TA. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433:760-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1544] [Cited by in RCA: 1639] [Article Influence: 82.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Boomsma RA, Geenen DL. Mesenchymal stem cells secrete multiple cytokines that promote angiogenesis and have contrasting effects on chemotaxis and apoptosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Li JK, Yang C, Su Y, Luo JC, Luo MH, Huang DL, Tu GW, Luo Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Acute Kidney Injury. Front Immunol. 2021;12:684496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O'Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3959] [Cited by in RCA: 4127] [Article Influence: 412.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brügger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2186] [Cited by in RCA: 2686] [Article Influence: 158.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1462] [Cited by in RCA: 1399] [Article Influence: 87.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | György B, Szabó TG, Pásztói M, Pál Z, Misják P, Aradi B, László V, Pállinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzás EI. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2667-2688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1350] [Cited by in RCA: 1637] [Article Influence: 116.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6920] [Cited by in RCA: 6558] [Article Influence: 1311.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Bruno S, Grange C, Deregibus MC, Calogero RA, Saviozzi S, Collino F, Morando L, Busca A, Falda M, Bussolati B, Tetta C, Camussi G. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles protect against acute tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1053-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Herrera Sanchez MB, Bruno S, Grange C, Tapparo M, Cantaluppi V, Tetta C, Camussi G. Human liver stem cells and derived extracellular vesicles improve recovery in a murine model of acute kidney injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gatti S, Bruno S, Deregibus MC, Sordi A, Cantaluppi V, Tetta C, Camussi G. Microvesicles derived from human adult mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischaemia-reperfusion-induced acute and chronic kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1474-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zou X, Zhang G, Cheng Z, Yin D, Du T, Ju G, Miao S, Liu G, Lu M, Zhu Y. Microvesicles derived from human Wharton's Jelly mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by suppressing CX3CL1. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Gu D, Zou X, Ju G, Zhang G, Bao E, Zhu Y. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived Extracellular Vesicles Ameliorate Acute Renal Ischemia Reperfusion Injury by Inhibition of Mitochondrial Fission through miR-30. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:2093940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Ju GQ, Cheng J, Zhong L, Wu S, Zou XY, Zhang GY, Gu D, Miao S, Zhu YJ, Sun J, Du T. Microvesicles derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells facilitate tubular epithelial cell dedifferentiation and growth via hepatocyte growth factor induction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Zhang W, Zhang J, Huang H. Exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress in LPS-acute kidney injury. Exp Cell Res. 2022;420:113332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Yun CW, Lee SH. Potential and Therapeutic Efficacy of Cell-based Therapy Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Acute/chronic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Wang J, Jia H, Zhang B, Yin L, Mao F, Yu J, Ji C, Xu X, Yan Y, Xu W, Qian H. HucMSC exosome-transported 14-3-3ζ prevents the injury of cisplatin to HK-2 cells by inducing autophagy in vitro. Cytotherapy. 2018;20:29-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Sun Z, Ning Y, Wu H, Guo S, Jiao X, Ji J, Ding X, Yu X. 14-3-3ζ targets β-catenin nuclear translocation to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and promote the balance between proliferation and apoptosis in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Cell Signal. 2023;111:110878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Jia H, Liu W, Zhang B, Wang J, Wu P, Tandra N, Liang Z, Ji C, Yin L, Hu X, Yan Y, Mao F, Zhang X, Yu J, Xu W, Qian H. HucMSC exosomes-delivered 14-3-3ζ enhanced autophagy via modulation of ATG16L in preventing cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10:101-113. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Yin S, Liu W, Ji C, Zhu Y, Shan Y, Zhou Z, Chen W, Zhang L, Sun Z, Zhou W, Qian H. hucMSC-sEVs-Derived 14-3-3ζ Serves as a Bridge between YAP and Autophagy in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:3281896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Zhu F, Chong Lee Shin OLS, Pei G, Hu Z, Yang J, Zhu H, Wang M, Mou J, Sun J, Wang Y, Yang Q, Zhao Z, Xu H, Gao H, Yao W, Luo X, Liao W, Xu G, Zeng R, Yao Y. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells employed exosomes to attenuate AKI-CKD transition through tubular epithelial cell dependent Sox9 activation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:70707-70726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Cao JY, Wang B, Tang TT, Wen Y, Li ZL, Feng ST, Wu M, Liu D, Yin D, Ma KL, Tang RN, Wu QL, Lan HY, Lv LL, Liu BC. Exosomal miR-125b-5p deriving from mesenchymal stem cells promotes tubular repair by suppression of p53 in ischemic acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2021;11:5248-5266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Wang SY, Xu Y, Hong Q, Chen XM, Cai GY. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury via let-7b-5p. Cell Tissue Res. 2023;392:517-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Yu Y, Chen M, Guo Q, Shen L, Liu X, Pan J, Zhang Y, Xu T, Zhang D, Wei G. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosome-derived miR-874-3p targeting RIPK1/PGAM5 attenuates kidney tubular epithelial cell damage. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023;28:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Zhang R, Zhu Y, Li Y, Liu W, Yin L, Yin S, Ji C, Hu Y, Wang Q, Zhou X, Chen J, Xu W, Qian H. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosomes alleviate sepsis-associated acute kidney injury via regulating microRNA-146b expression. Biotechnol Lett. 2020;42:669-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Zhu G, Pei L, Lin F, Yin H, Li X, He W, Liu N, Gou X. Exosomes from human-bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury via transferring miR-199a-3p. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:23736-23749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Zhang J, He W, Zheng D, He Q, Tan M, Jin J. ExosomalmiR1184 derived from mesenchymal stem cells alleviates cisplatinassociated acute kidney injury. Mol Med Rep. 2021;24:795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Zhang Y, Wang J, Yang B, Qiao R, Li A, Guo H, Ding J, Li H, Ye H, Wu D, Cui L, Yang S. Transfer of MicroRNA-216a-5p From Exosomes Secreted by Human Urine-Derived Stem Cells Reduces Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:610587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Liu W, Hu C, Zhang B, Li M, Deng F, Zhao S. Exosomal microRNA-342-5p secreted from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells mitigates acute kidney injury in sepsis mice by inhibiting TLR9. Biol Proced Online. 2023;25:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Zhang P, Wu S, He Y, Li X, Zhu Y, Lin X, Chen L, Zhao Y, Niu L, Zhang S, Li X, Zhu L, Shen L. LncRNA-Mediated Adipogenesis in Different Adipocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:7488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Sun Z, Wu J, Bi Q, Wang W. Exosomal lncRNA TUG1 derived from human urine-derived stem cells attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by interacting with SRSF1 to regulate ASCL4-mediated ferroptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | He Y, Li X, Huang B, Yang Y, Luo N, Song W, Huang B. Exosomal circvma21 derived from adipose-derived stem cells alleviates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by targeting mir-16-5p. Shock. 2023;60:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Yang B, Wang J, Qiao J, Zhang Q, Liu Q, Tan Y, Wang Q, Sun W, Feng W, Li Z, Wang C, Yang S, Cui L. Circ DENND4C inhibits pyroptosis and alleviates ischemia-reperfusion acute kidney injury by exosomes secreted from human urine-derived stem cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2024;391:110922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Lee PW, Wu BS, Yang CY, Lee OK. Molecular Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:11406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Sávio-Silva C, Soinski-Sousa PE, Balby-Rocha MTA, Lira ÁO, Rangel ÉB. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in acute kidney injury (AKI): review and perspectives. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2020;66 Suppl 1:s45-s54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Han Q, Wang X, Ding X, He J, Cai G, Zhu H. Immunomodulatory Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Drug-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Front Immunol. 2021;12:683003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Burks SR, Nagle ME, Bresler MN, Kim SJ, Star RA, Frank JA. Mesenchymal stromal cell potency to treat acute kidney injury increased by ultrasound-activated interferon-γ/interleukin-10 axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:6015-6025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Sun W, Zhu Q, Yan L, Shao F. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate acute kidney injury via miR-107-mediated regulation of ribosomal protein S19. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Makhlough A, Shekarchian S, Moghadasali R, Einollahi B, Dastgheib M, Janbabaee G, Hosseini SE, Falah N, Abbasi F, Baharvand H, Aghdami N. Bone marrow-mesenchymal stromal cell infusion in patients with chronic kidney disease: A safety study with 18 months of follow-up. Cytotherapy. 2018;20:660-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Peired AJ, Sisti A, Romagnani P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Kidney Disease: A Review of Clinical Evidence. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4798639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Aghajani Nargesi A, Lerman LO, Eirin A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for kidney repair: current status and looming challenges. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |