Published online Mar 26, 2025. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.100079

Revised: December 4, 2024

Accepted: February 5, 2025

Published online: March 26, 2025

Processing time: 226 Days and 17 Hours

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a fatal and heterogeneous disease. While bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) have shown promise in ALI repair, their efficacy is compromised by a high apoptotic percentage. Preliminary findings have indicated that long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)-ENST expression is markedly downregulated in MSCs under ischemic and hypoxic conditions, establishing a rationale for in vitro exploration.

To elucidate the role of lncRNA-ENST00000517482 (lncRNA-ENST) in modulating MSC apoptosis.

Founded on ALI in BEAS-2B cells with lipopolysaccharide, this study employed a transwell co-culture system to study BMSC tropism. BMSCs were genetically modified to overexpress or knockdown lncRNA-ENST. After analyzing the effects on autophagy, apoptosis and cell viability, the lncRNA-ENST/miR-539/c-MYC interaction was confirmed by dual-luciferase assays.

These findings have revealed a strong correlation between lncRNA-ENST levels and the apoptotic and autophagic status of BMSCs. On the one hand, the over-expression of lncRNA-ENST, as determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 assays, increased the expression of autophagy markers LC3B, ATG7, and ATG5. On the other hand, it reduced apoptosis and boosted BMSC viability. In co-cultures with BEAS-2B cells, lncRNA-ENST overexpression also improved cell vitality. Additionally, by downregulating miR-539 and upregulating c-MYC, lncRNA-ENST was found to influence mitochondrial membrane potential, enhance BMSC autophagy, mitigate apoptosis and lower the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β. Collectively, within the in vitro framework, these results have highlighted the therapeutic potential of BMSCs in ALI and the pivotal regulatory role of lncRNA-ENST in miR-539 and apoptosis in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BEAS-2B cells.

Our in vitro results show that enhanced lncRNA ENST expression can promote BMSC proliferation and viability by modulating the miR-539/c-MYC axis, reduce apoptosis and induce autophagy, which has suggested its therapeutic potential in the treatment of ALI.

Core Tip: In this research, we established an acute lung injury (ALI) model and manipulated long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)-ENST levels in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) using a lentiviral system. We discovered that lncRNA-ENST00000517482 is a pivotal regulator of BMSC apoptosis and autophagy in ALI. Modulating lncRNA-ENST00000517482 not only reduces apoptosis and induces autophagy in BMSCs but also enhances their viability, offering a novel approach to enhance ALI treatment efficacy via the miR-539/c-MYC axis.

- Citation: Shen YZ, Yang GP, Ma QM, Wang YS, Wang X. Regulation of lncRNA-ENST on Myc-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis in mesenchymal stem cells: In vitro evidence implicated for acute lung injury therapeutic potential. World J Stem Cells 2025; 17(3): 100079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v17/i3/100079.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v17.i3.100079

The typical symptoms of acute lung injury (ALI) include acute respiratory failure with tachypnea, refractory cyanosis, decreased lung compliance, and diffuse pulmonary alveolar infiltrates on chest X-ray[1]. Recently, in addition to the better understanding of the pathophysiology of ALI, there has also been some progress in clinical treatment[2-4]. For example, some treatment concepts and methods, such as lung-protective ventilation, fluid management and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, have been applied widely. However, the overall clinical mortality rate has not signi

Extracellular vesicles derived from BMSCs can effectively alleviate pulmonary edema, extensive alveolar hemorrhage, inflammatory cell infiltration, and reduce lung injury scores[9]. Notwithstanding, after injecting a large number of BMSCs into the animals’ bodies, most of the BMSCs underwent apoptosis or were lost for unknown reasons within a few days after being transferred to the damaged lung tissue. Ultimately, the number of cells that differentiated into the corresponding functional cells was very limited, which greatly affected the therapeutic efficacy[11]. Chen et al[7] confirmed that MSCs transplanted into the lungs exhibited significant apoptosis in ALI caused by ischemia-reperfusion. Autophagy, the primary mechanism for delivering various cellular components to lysosomes for degradation and recycling, plays a crucial protective role in a variety of diseases[12,13]. It was concluded that reducing MSCs apoptosis and improving their transplantation rate and survival rate were key to enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs.

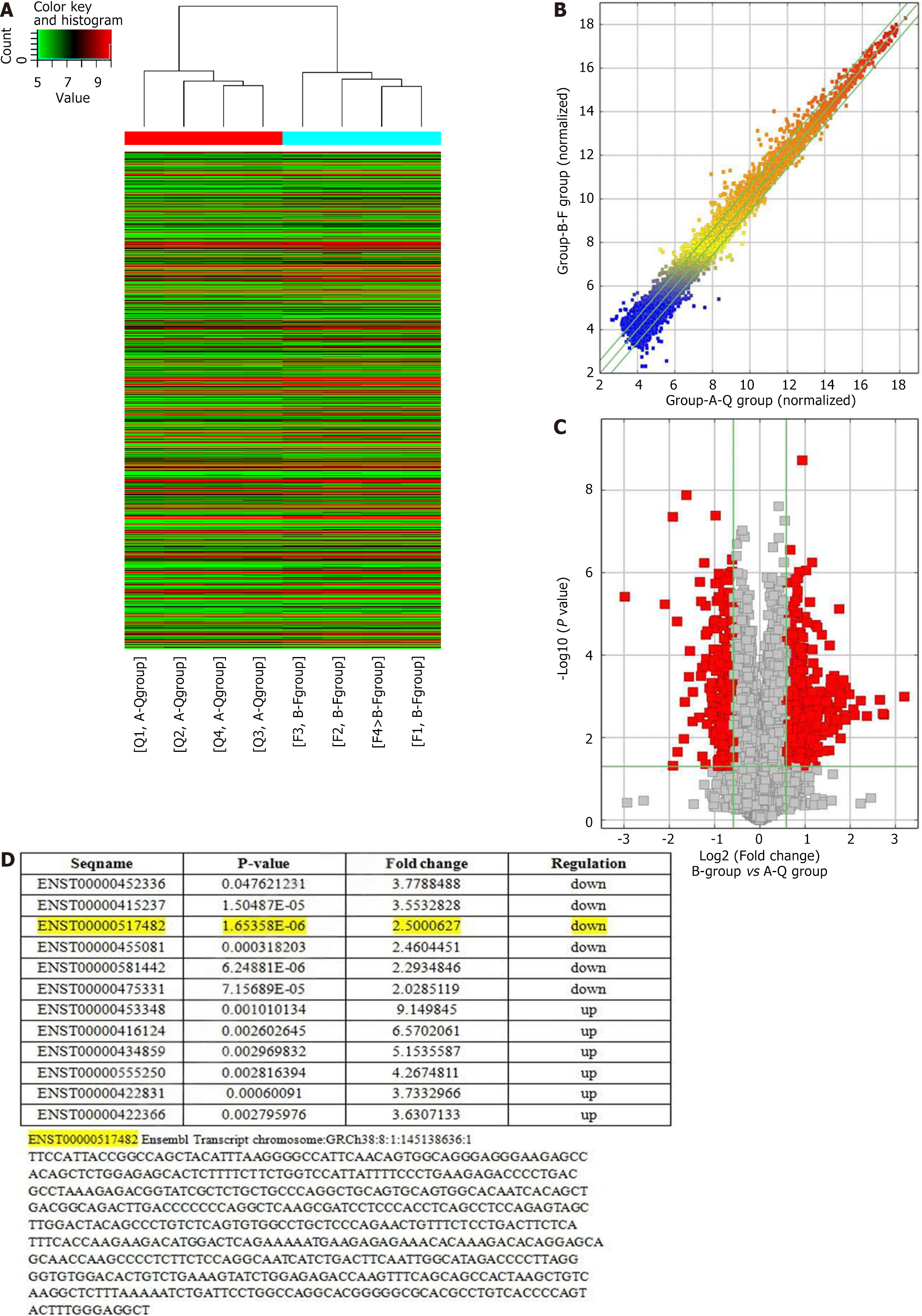

Mitochondrial apoptosis control is regulated by multiple signaling molecules, including long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). There is growing evidence that lncRNAs are closely associated with the occurrence and progression of various diseases, such as myocardial infarction[14] and cancer[15,16]. In previous experiments, MSCs under hypoxic-ischemic conditions were cultured. Furthermore, a gene chip (Arraystar LncRNA V3.0 Microarray, United States) was employed to screen six significantly downregulated lncRNAs, including lncRNA-ENST00000517482 (lncRNA-ENST). According to small interfering RNA, it was found that MSC apoptosis could be greatly enhanced by interference with lncRNA-ENST, which was not b achieved by interference with the other five lncRNAs. Therefore, lncRNA-ENST was selected as the target gene for further experiments. ENST can promote the progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway[17] and inhibit the progression of renal cancer through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway[18].

In mRNA-related studies, microRNAs (miRNAs) are generally considered to be downstream targets of lncRNAs, which can regulate the expression of target mRNAs by competitively binding with miRNAs. By virtue of the RNA22 prediction software, the potential binding sites between lncRNA ENST and miR-539 were identified, which may have regulatory effects on mitochondrial-related proteins. This mechanism of indirectly regulating target mRNAs is known as the competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network[19,20].

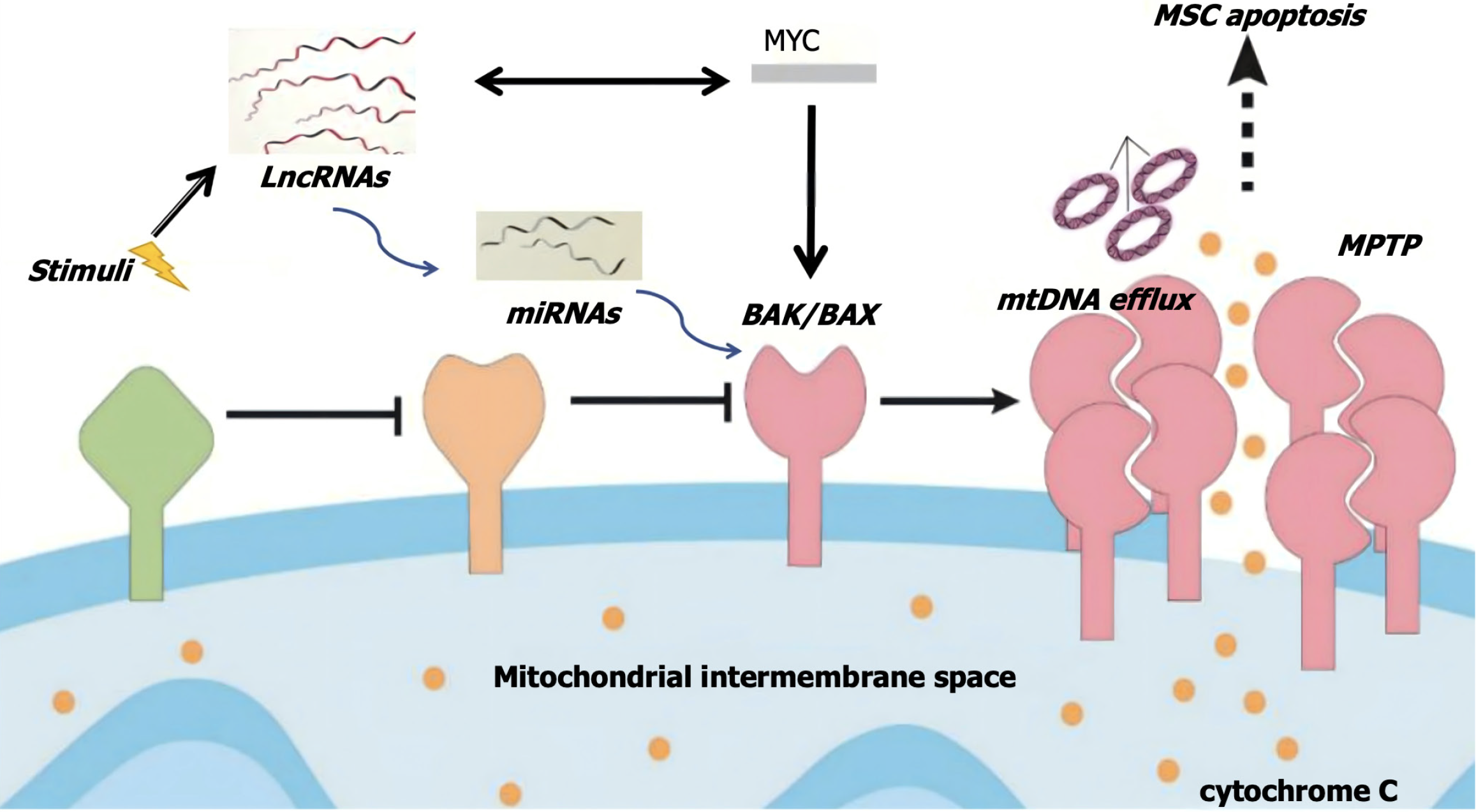

There is a close relationship between C-MYC gene and lncRNA, which can participate in the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis through the mitochondrial apoptosis channel[21,22]. Therefore, it can be assumed that when stem cells are subjected to apoptotic stimuli such as ischemia and hypoxia, the expression of lncRNA-ENST in the cell nucleus may be downregulated, leading to changes in mitochondrial outer membrane potential. The formation of permeability transition pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane can then result in increased permeability. Soluble proteins in the intermembrane space and pro-apoptotic factors that enter the cytoplasm, such as cytochrome C, further accelerate the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and induce stem cell apoptosis. This study aimed to validate the apoptotic regulatory pathway of stem cells involving “lncRNA-miRNA-MYC-mitochondrial apoptosis”.

BMSCs obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Catalog Number: HUM-iCell-s011) were cultured using the Non-Serum Culture System of Primary Mesenchymal Stem Cells of iCell. The obtained BMSCs were placed in complete culture medium at 37°C with 5% CO2. Our in vitro stem cell study, devoid of animal testing or human samples, complied with scientific and safety protocols, utilizing only commercially available, de-identified cell lines without ethical or privacy concerns.

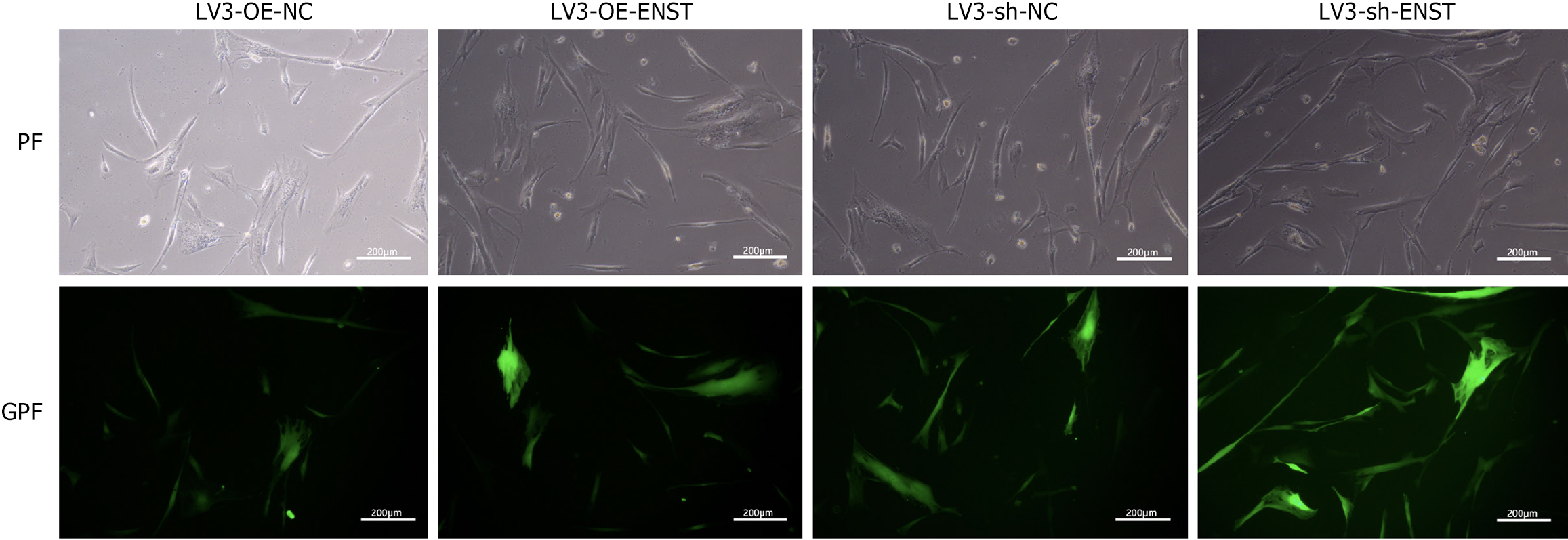

The infection solution was added to the BMSCs culture dish and an appropriate amount of virus was also added based on the cell’s multiplicity of infection value. After 18-20 hours of infection, the freshly-prepared medium replaced the ready-prepared medium. After 72 hours, microscopy was employed to observe the fluorescence and infection efficiency.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, Trizol (Sigma) and an ND-1000 spectrophotometer were utilized to extract the total RNA from cell samples and determine the RNA concentration and purity, respectively. Only samples with an absorbance ratio of 260 nm/280 nm around 2.0 and a ratio of 260 nm/230 nm between 1.9 and 2.2 were considered for further study.

SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was adopted to quantify mRNA levels found using the quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The relative levels of the target gene were determined by the -ΔΔCt method. TaqMan miRNA RT-Real Time PCR was employed to detect the levels of miR-539. The TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Vazyme Scientific) was utilized to synthesize single-stranded cDNA, followed by amplification using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). U6 snRNA was used for normalization. The relative levels of miRNA were determined by means of the -ΔΔCt method.

The primer sequences are as follows: Forward 5’-TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA-3’ and reverse 5’-CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3’ for human GAPDH, forward 5’-TGCTCCCAGAACTGTTTCTCCTGA-3’ and reverse 5’-CTTGGTTGCTGCTCCTGTGTCTT-3’ for human ENST0000051748, forward 5’-GCGGAGAAATTATCCTTG-3’ and reverse 5’-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3’ for human miR-539, forward 5’-GGCTCCTGGCAAAAGGTCA-3’ and reverse 5’-CTGCG

The cell viability of BMSCs after different interventions was determined using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, LabLead, CK001-5000T). Cells in suspension, counted using a hemocytometer, were plated to form a gradient of cell concentrations. Determined after 2 to 4 hours of cell incubation after seeding, the optical density values were measured, followed by the addition of CCK-8 reagent.

After collecting cells treated with different interventions, they were incubated with annexin V-APC and propidium iodide. According to the detection of apoptotic cells by flow cytometry, the results were analyzed using FlowJo software (v10.4.1) (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, United States).

A lysis buffer [(RIPA lysis buffer):(proteinase inhibitor) = 99:1] was employed to perform the protein extraction in the BMSCs culture. After determining protein concentration by the BCA method, electrophoresis, wet transfer, blocking and antibody incubation were carried out. Following color development, the gel was photographed and the expression level of the target protein was analyzed using a gel imaging system. The antibodies used in the study were as follows: LC3B (Abcam, #ab48394, 1:3000), ATG7 (CST, #8558, 1:1000), GAPDH (Proteintech, #60004-1-Ig, 1:30000), goat anti-rabbit (Beyotime, #A0208, 1:3000), and goat anti-mouse (Beyotime, #A0216, 1:3000).

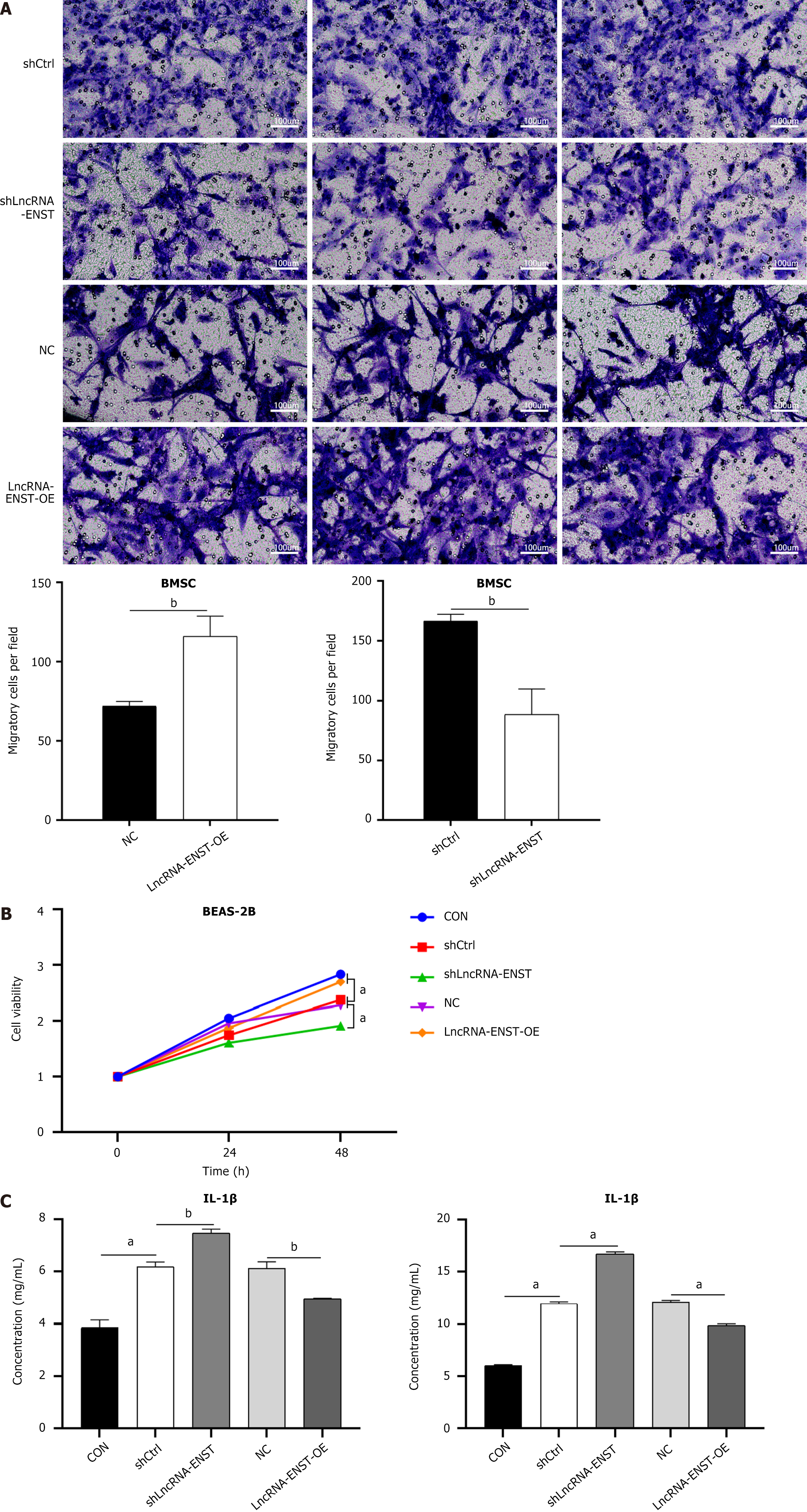

Cell migration experiments were performed using the Transwell system (Corning, NY, United States) to evaluate the migratory capacity of BMSCs in an indirect co-culture system. BMSCs were seeded in the upper chamber of a Transwell, which was coated with Matrigel. The lower chamber contained BEAS-2B lung epithelial cells treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 μg/mL) for 12 hours to simulate an ALI-like inflammatory environment. The biological conditions of ALI were simulated by stimulating lung epithelial cells or macrophages with LPS. This setup allowed for indirect interaction between BMSCs and BEAS-2B cells through soluble factors in the shared medium, without direct cell-to-cell contact. The migration of BMSCs was assessed after a 12-hour incubation period by staining the cells that migrated to the lower surface of the membrane, which was then quantified using a cell counting method.

The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines in the culture medium, including interleukin (IL)-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit (ML002293) and IL-1β ELISA Kit (SEKM-0002), were determined by an ELISA assay kit.

DMEM (10 μL) was thoroughly mixed with the desired plasmid (lncRNA-ENST or c-MYC)-3’ untranslated region (0.16 μg) and the hsa-miR-539-5p or negative control (NC) (5 pmol). Then, 10 μL of DMEM and 0.3 μL of transfection reagent were added to the mixture, which was transfected into 293T cells. After 48 hours of transfection, the dual-luciferase® reporter gene detection system was employed to perform a dual luciferase assay of the cells following the manufacturer’s instructions.

For each sample in every group, three parallel experiments were set up and each experiment was independently repeated three times. The data from the experiments in each group conformed to normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, which are represented as the mean ± SD. GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 was used to analyze the data. Addi

In the preliminary study, we established a BMSC apoptosis model by simulating pulmonary epithelial cells, and screened and identified ischemia and hypoxia related lncRNA-ENST. We obtained the clustering analysis chart (Figure 1A) and the normalized lncRNA expression values (Figure 1B), as well as the volcano plot (Figure 1C). Additionally, through gene chip screening (Arraystar LncRNA V3.0 Microarray, United States) in MSCs cultured under ischemia and hypoxia conditions, we found that the expression of lncRNA-ENST and five other lncRNAs was significantly reduced, suggesting that they may be associated with ischemia and hypoxia-induced apoptosis, while the expression of six other lncRNAs was significantly increased (Figure 1D)

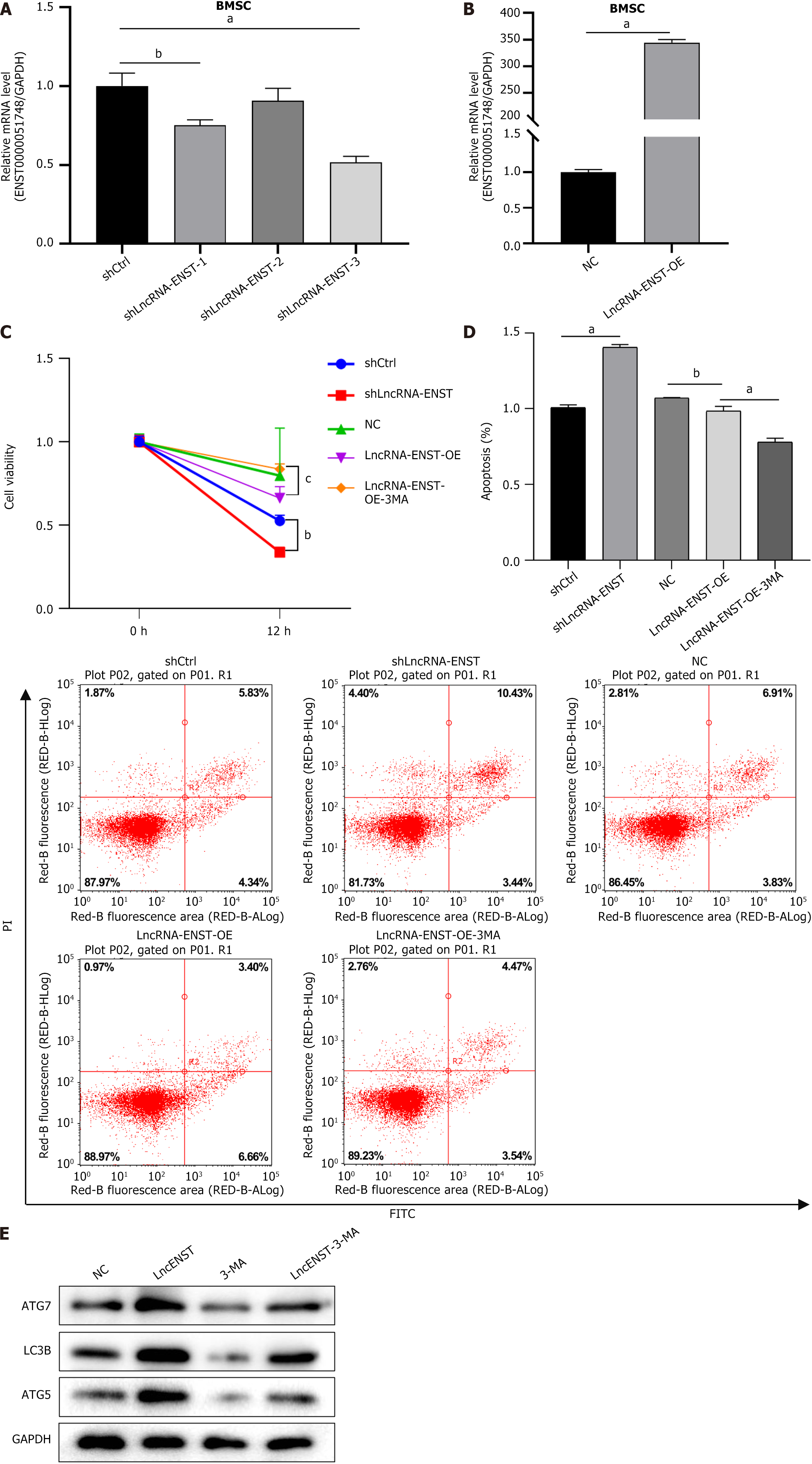

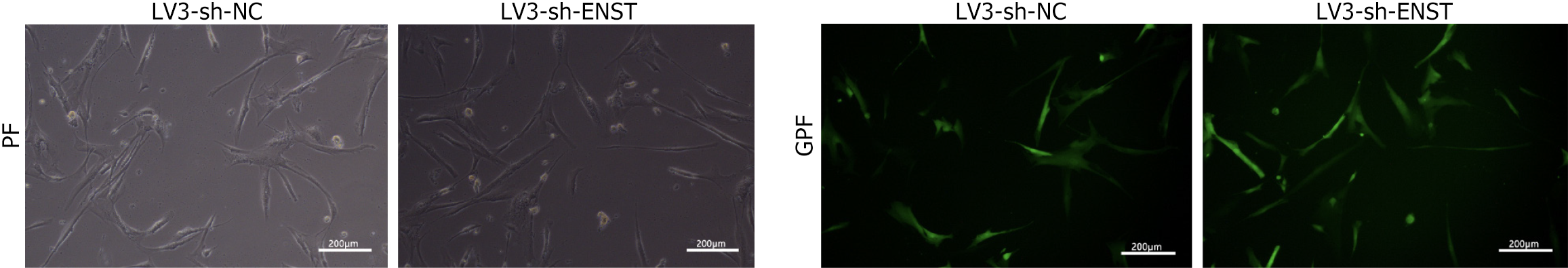

As shown in Figure 2, observations under an inverted fluorescence microscope demonstrated high transfection efficiency of lentiviral transduction. Knockdown BMSC was constructed by packaging lncRNA-ENST with lentivirus, and quantitative PCR was used to detect the knockdown efficiency of lncRNA-ENST. The results showed that compared to the sh-NC group, the expression efficiency of lncRNA-ENST was significantly reduced in the shlncRNA-ENST group (Figure 3A). Similarly, overexpressed BMSC was constructed by packaging lncRNA-ENST with lentivirus, and quan

A transwell chamber was used to construct an in vitro indirect co-culture model. After treating lung epithelial cells BEAS-2B with LPS for 12 hours to induce ALI, the migration level of BMSCs in the ENST knockdown group was decreased, and the viability of BEAS-2B cells was reduced. In contrast, the migration level of BMSCs in the ENST overexpression group was increased, and the viability of BEAS-2B cells was enhanced (Figure 4A and B). At the same time, ELISA experiments observed that the overexpression of ENST significantly decreased the expression levels of related factors IL-1β and IL-6 (Figure 4C).

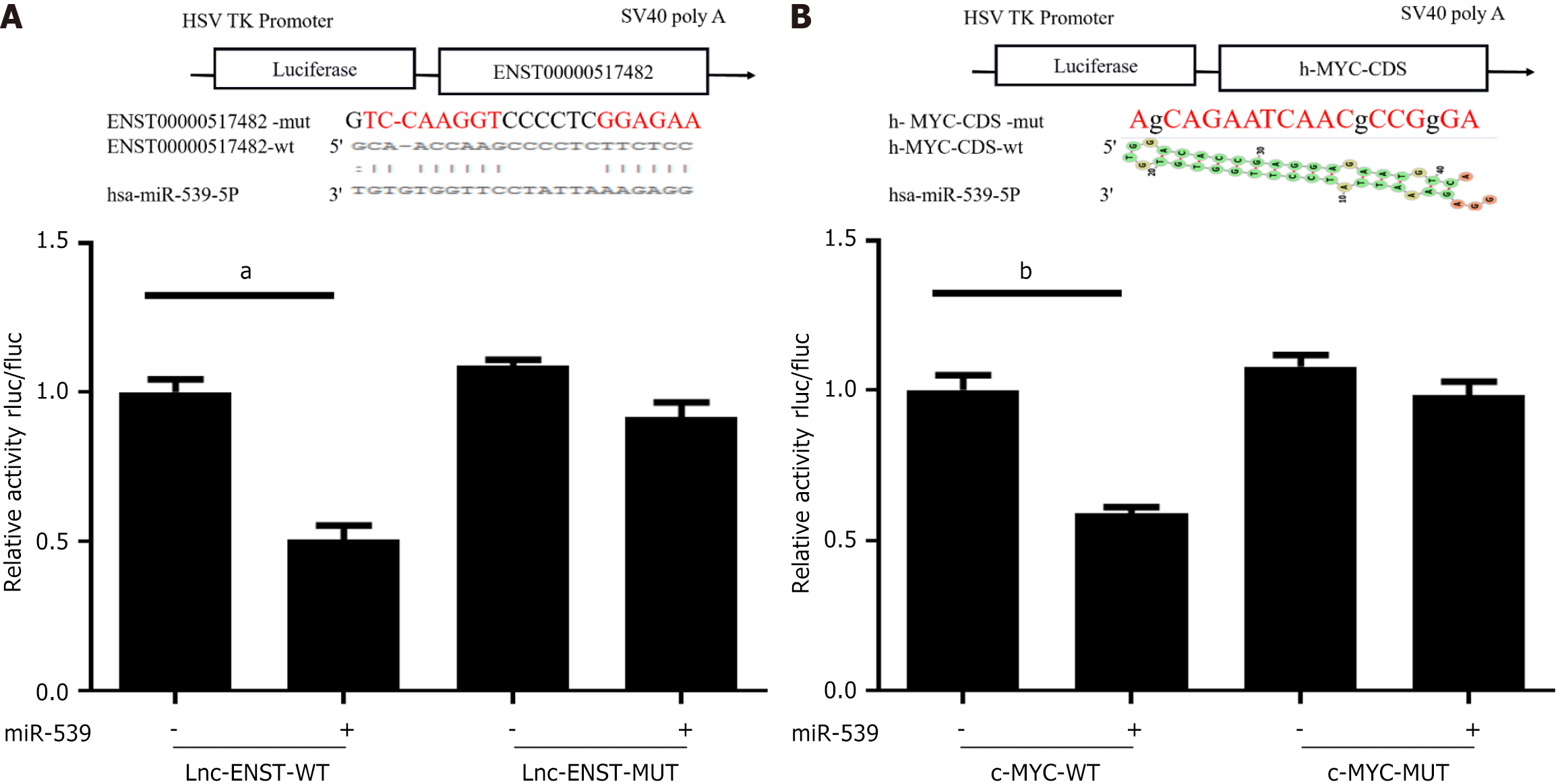

In preliminary work, we used the RNA22 prediction software to identify potential binding sites between lncRNA-ENST and miR-539. Through luciferase assays, we found that the mimic of miR-539-5p significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of the wild-type ENST reporter gene but had no significant effect on the luciferase activity of the mutant ENST reporter gene. Additionally, the level of ENST was overexpressed or silenced in BMSCs (Figure 5A).

Similarly, the luciferase reporter assay revealed the presence of miR-539 binding sites in the 3’ untranslated region of c-MYC. The luciferase activity of the wild-type c-MYC reporter gene was inhibited by the mimic of miR-539-5p, while no significant change was observed in the luciferase activity of the mutant c-MYC reporter gene (Figure 5B).

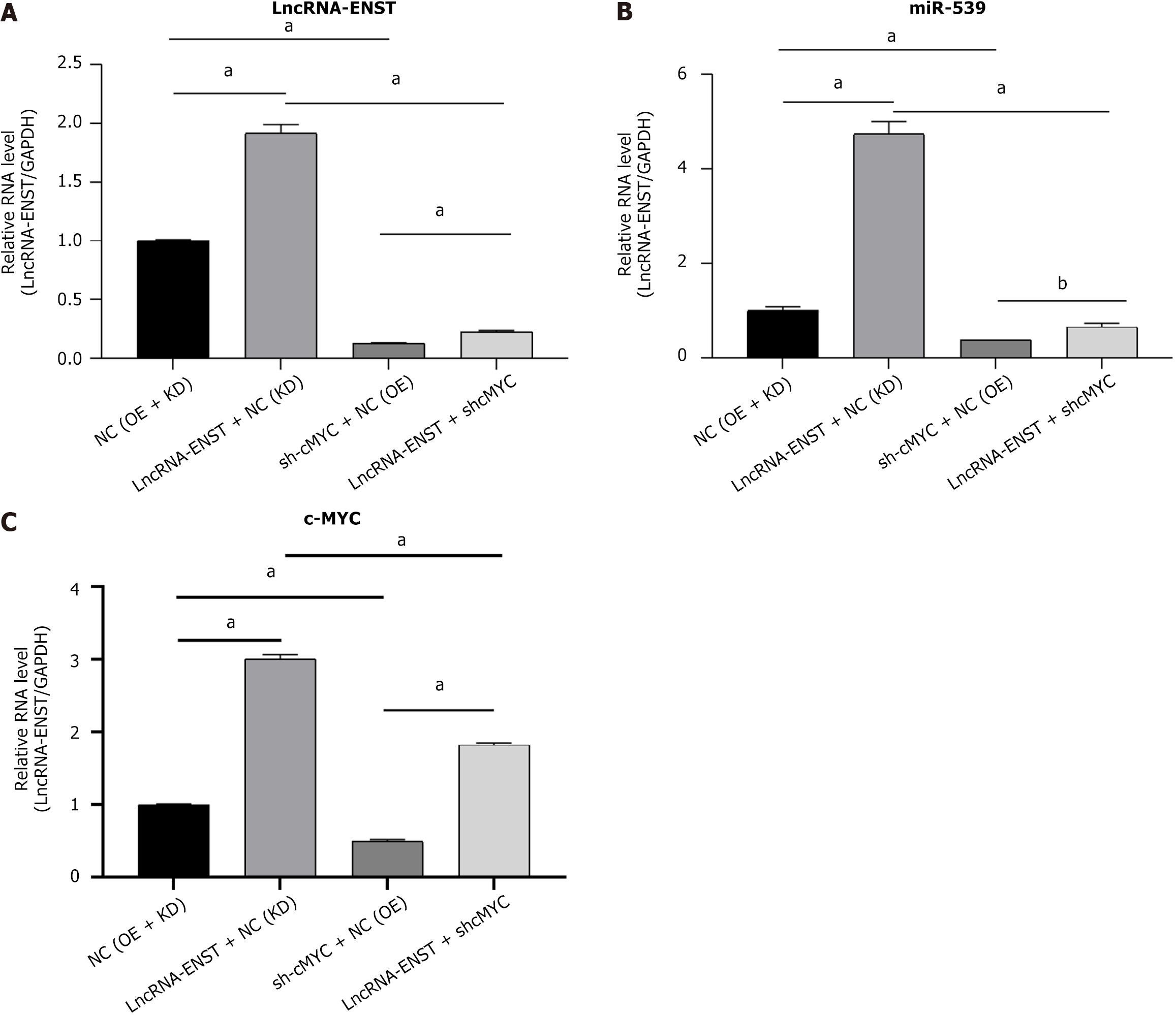

Through luciferase reporter assays, we validated the binding sites between lncRNA ENST and miR-539-5P, as well as the binding sites between miR-539-5P and c-MYC. As shown in Figure 6, observations under an inverted fluorescence microscope demonstrated high transfection efficiency of lentiviral transduction. Using lentivirus packaging, we constructed plasmids for the overexpression of lncRNA ENST and the knockdown of c-MYC. Through quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR, we found that successful overexpression of ENST resulted in downregulation of miR-539-5P expression and upregulation of c-MYC expression. After functionally silencing c-MYC, we also observed the same effects: Silencing c-MYC led to downregulation of lncRNA-ENST expression and upregulation of c-MYC expression. By combining the binding sites among the three genes, we discovered that lncRNA-ENST is involved in regulation through the miR-539-5P/c-MYC axis (Figure 7).

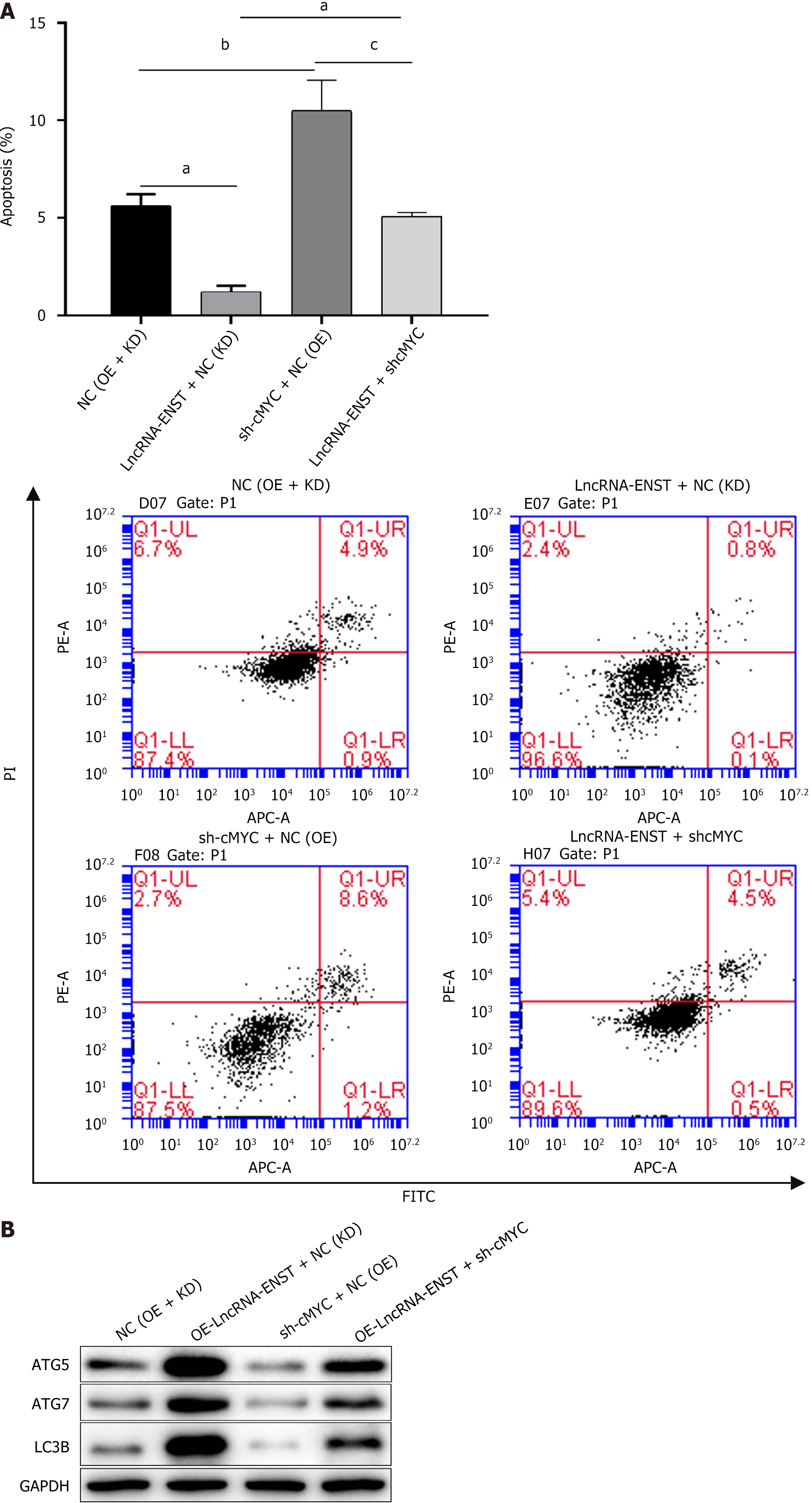

After identifying the ceRNA regulatory relationship among the three genes, we detected apoptosis and autophagy of BMSCs. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the apoptosis level of the OE-lncRNA-ENST + NC (KD) group was significantly decreased, while the apoptosis level of the sh-cMYC + NC (OE) group was significantly increased, and the apoptosis levels and statistical chart are shown in Figure 8A. Western blot analysis of autophagy-related proteins indicated that the expression of autophagy-related proteins LC3B, ATG7, and ATG5 was significantly upregulated in the OE-lncRNA-ENST + NC (KD) group, whereas the expression levels of autophagy-related proteins were significantly downregulated in the sh-cMYC + NC (OE) group (Figure 8B). This suggests that lncRNA-ENST induces autophagy in BMSCs through the miR-539-5p/c-MYC axis, reducing their apoptosis level.

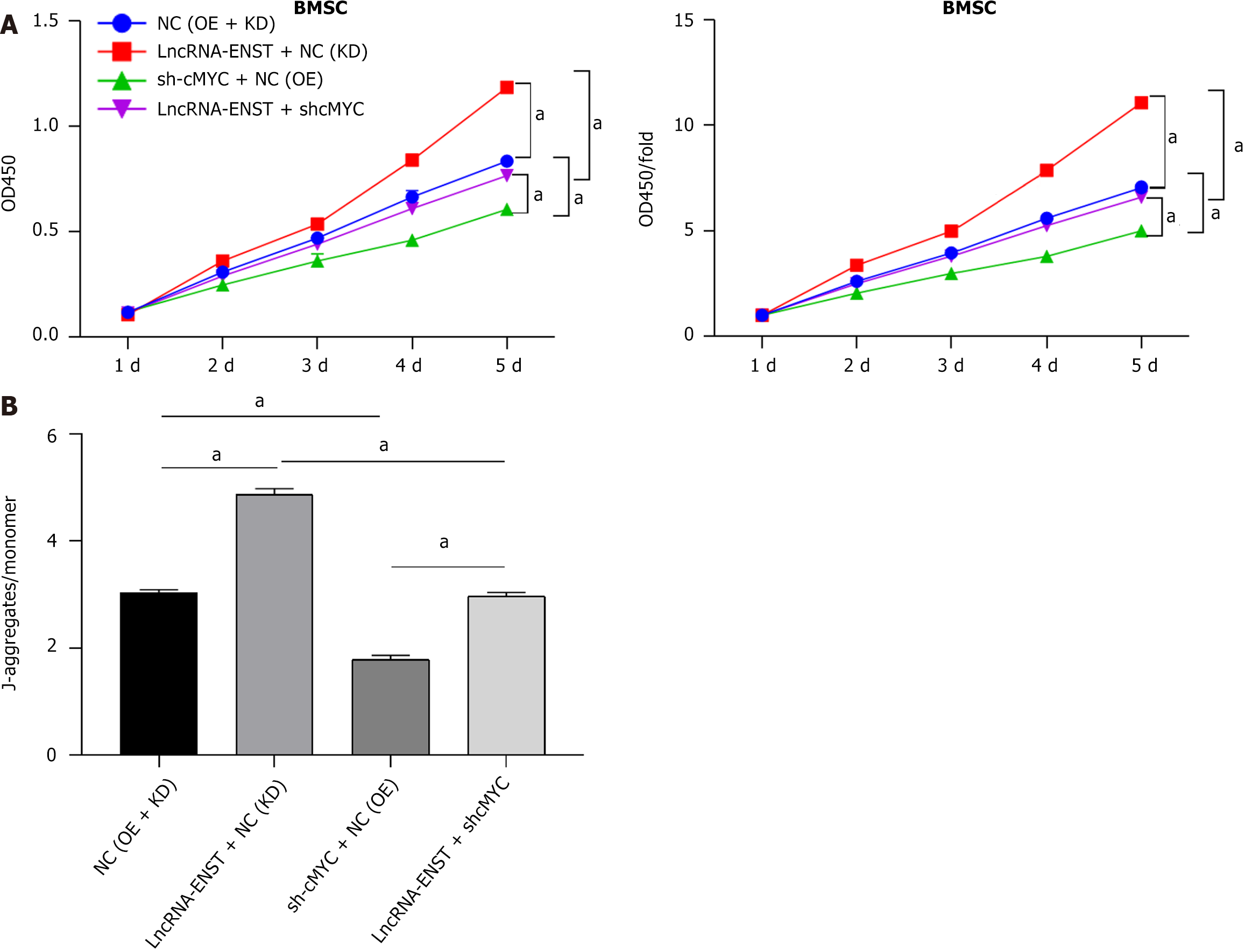

We constructed overexpression plasmids for LncRNA-ENST and knockdown plasmids for c-MYC, packaged lentivirus, and infected BMSCs. We assessed cell damage using the CCK-8 assay to detect BMSC viability. The results showed that cell viability in the OE-lncRNA-ENST + NC (KD) group was significantly increased (P < 0.001), while cell viability in the sh-cMYC + NC (OE) group was significantly decreased (Figure 9A). In the JC-1 staining experiments to detect mito

Autophagy and apoptosis are two interrelated mechanisms that occur in response to cellular stress. However, the molecular interactions between these two mechanisms have not been fully understood. It is well known that autophagy serves as a cellular protective mechanism under physiological conditions, which encompasses the negative regulation of cell apoptosis, and vice versa. Recent research has confirmed the cross-talk between autophagy and apoptosis, which was manifested through the regulation of shared pathways and genes. These regulated genes consisted of p53, Atg5, Bcl-2 and others. Stimulation leading to the activation or inhibition of these genes would have effects on the cellular fate through specific pathways[23].

As a hot topic of research, lncRNA ENST has played a significant role in numerous biological processes, such as epigenetic regulation, cell cycle control, regulation of apoptosis and senescence, cell differentiation, transcription and post-transcriptional regulation[24-26]. MYC is an important regulatory gene in the process of tumorigenesis[27]. The encoded protein by c-MYC gene, which is a vital intracellular transcription factor as a proto-oncogene, mediates the transfer of biological signals from extracellular to intracellular to the nucleus. Moreover, it is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, metabolism and apoptosis. The normal c-MYC gene maintains cell division and proliferation. Notwithstanding, if the external signal changes or the cell genetic genes are damaged, the c-MYC gene will induce cell apoptosis[28,29].

This study has demonstrated that the lncRNA-miR-539-c-MYC axis selectively regulates the apoptosis and autophagy of BMSCs and may potentially serve as a novel pathway to enhance the survival rate of BMSCs and ALI. Through small interfering RNA interference, it was found that the interference with lncRNA-ENST led to a significant increase in MSCs apoptosis, while the interference with the other 5 lncRNAs had little effects on MSCs apoptosis. Furthermore, the luciferase reporter assay demonstrated the binding sites between lncRNA ENST and miR539, as well as between miR539 and c-MYC. Therefore, the scientific hypothesis has been proposed that when stem cells are stimulated by apoptotic signals such as ischemia or hypoxia, the downregulation of nuclear lncRNA-ENST, in cooperation with MYC, induces conformational changes in the pro-apoptotic protein BAX/BAK, located in the cytoplasm. These changes bring about the translocation to the outer mitochondrial membrane and help the formation of pores for release, thus enhancing mitochondrial membrane permeability. Furthermore, by allowing the soluble proteins in the intermembrane space and pro-apoptotic factors such as cytochrome C to enter the cytoplasm, apoptosis in stem cells is ultimately triggered (Figure 10).

This study has determined the effects of lncRNA-ENST on the apoptosis of BMSCs under conditions of ischemia and hypoxia. The experimental studies of knockdown and overexpression have demonstrated that lncRNA expression within a certain range can enhance the autophagy of MSCs and reduce the apoptosis rate. Under conditions such as ischemia and hypoxia, the apoptosis of MSCs was regulated by various aspects of lncRNA. First, the expression of lncRNA-ENST can enhance autophagy by increasing the expression of autophagy-related proteins, and make full use of intracellular injurious substances to improve the stress ability of cells and lower cell apoptosis. Moreover, inhibition of its expression will lead to a further increase in cell apoptosis. However, it has found that when autophagy inhibitors were added to overexpressed lncRNA-ENTS, the apoptosis level of cells was significantly decreased. It can be assumed that cells can reduce apoptosis by raising autophagy to a certain extent, but when the autophagy level is too high, apoptosis will increase. At the same time, the expression of ENST can also reduce cell apoptosis by enhancing the migration ability of BMSCs, increasing cell activity and reducing the expression of inflammation-related factors IL-6 and IL-1β. The mechanism may be related to the down-regulation of miRNA-539 and its synergistic effect with c-MYC gene and the decreased expression of apoptosis-related proteins.

Through the dual luciferase system, the binding sites between lncRNA and mirNA-539 and the binding sites between miRNA and c-MYC gene, even encompassing the interaction through binding sites, were verified. Previous studies have confirmed that lncRNA and miRNA can interact with each other through binding, lncRNA can regulate miRNA expression through competitive binding and miRNA can influence its activity after binding with lncRNA[30,31]. For example, during the occurrence of colorectal cancer, lncRNA can reduce the expression of miRNA through its binding with miRNA, thus affecting the biological behavior of tumor cells[32]. In addition, the genetic analysis of leukemia cells has shown that when miRNA-155 is overexpressed in leukemia cell lines, the expression level of target lncRNA is significantly decreased; conversely, the opposite is also true[33]. This study found that the expression of lncRNA was negatively correlated with that of miRNA, that is, the overexpressed lncRNA could reduce the apoptosis of MSCs by inhibiting the expression of miRNA. At present, the role of miRNAs is mainly based on the hypothesis of the competitive internal RNA (ceRNA) network, that is, miRNAs can affect the expression of target mRNA through the competitive role of lncRNA. In this experiment, the effect of miRNA-539 on the expression of c-MYC gene is through direct binding, but whether it also has an effect on the expression of c-MYC gene through indirect influence on lncRNA expression requires further study. In the validation experiments of the lncRNA-miRNA-c-MYC axis, it has found that lncRNA overexpression promoted the expression of c-MYC gene. In the case of lncRNA overexpression, knocking down c-MYC gene could lead to a decrease in lncRNA expression, while in the case of normal lncRNA expression, lncRNA could reduce the expression of c-MYC gene. Knockdown of c-MYC gene led to increased lncRNA expression.

A possible explanation for this is that the influence of the c-MYC gene on lncRNA is associated with the expression status of the lncRNA itself. Through detection of the miR539 gene, it was found that overexpression of lncRNA can reduce miR539 expression, while knockdown of the c-MYC gene can increase miR539 expression. The results of protein detection related to cell activity, apoptosis and autophagy are consistent with those of the lncRNA knockdown/overexpression experiments. Therefore, it is reasonable that the lncRNA-miRNA-c-MYC axis can induce changes in autophagy, cell activity and inflammatory factors in BMSCs, thereby exerting an influence on the level of cell apoptosis.

As important organelles in MSCs, mitochondria not only provide ATP in MSCs, but also transmit extracellular and intracellular signals when MSCs are subjected to environmental stress or injury. Persistent mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to hypoxia-induced MSCs injury, thus causing reduced stem cell therapy efficacy after MSCs apoptosis and inhalation injury[34,35]. BAX/BAK is an important protein that influences mitochondrial fate by regulating mitochondrial permeability and further regulates mitochondrial transport by influencing mitochondrial permeability transition pores[36-38]. The detection of mitochondrial membrane potential by JC-1 staining has shown that lncRNA overexpression can result in a significant increase in mitochondrial membrane potential, while knockdown of c-MYC gene can lead to a significant reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential. These results revealed that the lncRNA-miRNA-c-MYC axis can change mitochondrial membrane potential. Specifically, the membrane potential is impacted by the change in relevant proteins on the mitochondrial membrane, which then leads to changes in mitochondrial permeability. In addition, it has also been indirectly verified that the lncRNA-miRNA-c-MYC axis can change the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane by regulating BAX/BAK, thus affecting the apoptosis level of cells.

At present, there is a lot of evidence that lncRNA can control mitochondrial function and change disease prognosis by regulating the dynamics of mitochondrial-related proteins and mitochondrial channel proteins[39]. However, even outside the field of stem cell research, there are no studies to demonstrate the specific association and mechanism of action between lncRNA and c-MYC. This study has revealed that the regulation of BMSCs apoptosis may be realized through a synergistic effect between the two. Whether lncRNA and c-MYC gene interact with each other through direct binding or through miR539 as an intermediate to achieve mutual influence, and whether miR539 affects c-MYC gene indirectly through lncRNA, requires further investigation.

It should be noted that this research also has limitations. Specifically, the reliance on in vitro experiments and an LPS-induced ALI model may not fully represent the intricacies of the human disease. While these in vitro experiments have suggested that lncRNA-ENST has therapeutic potential for ALI, this study has emphasized that these findings are preliminary and require validation with in vivo models to confirm their clinical translational potential. Future research must bridge this gap by extending the investigation to in vivo environments, ensuring that our understanding of the role of lncRNA-ENST in ALI is both comprehensive and clinically relevant.

This study has proved that lncRNA-ENST can reduce pulmonary epithelial cell apoptosis in the treatment of ALI, thereby enhancing the therapeutic effects. Furthermore, it has revealed the potential of the lncRNA-ENST-miR539-c-MYC axis in treating ALI by elucidating its regulatory mechanism. However, these results are based on in vitro experiments, and further in vivo studies are required to validate the therapeutic potential of lncRNA-ENST in ALI treatment.

The authors express their gratitude to the individuals who participated in this study.

| 1. | Mokrá D. Acute lung injury - from pathophysiology to treatment. Physiol Res. 2020;69:S353-S366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Curley GF, McAuley DF. Stem cells for respiratory failure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ho MS, Mei SH, Stewart DJ. The Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Effects of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:2606-2617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhou Z, Hua Y, Ding Y, Hou Y, Yu T, Cui Y, Nie H. Conditioned Medium of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Involved in Acute Lung Injury by Regulating Epithelial Sodium Channels via miR-34c. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:640116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bos LDJ, Ware LB. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: causes, pathophysiology, and phenotypes. Lancet. 2022;400:1145-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 116.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li M, Yang J, Wu Y, Ma X. miR-186-5p improves alveolar epithelial barrier function by targeting the wnt5a/β-catenin signaling pathway in sepsis-acute lung injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;131:111864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen S, Chen L, Wu X, Lin J, Fang J, Chen X, Wei S, Xu J, Gao Q, Kang M. Ischemia postconditioning and mesenchymal stem cells engraftment synergistically attenuate ischemia reperfusion-induced lung injury in rats. J Surg Res. 2012;178:81-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao R, Wang L, Wang T, Xian P, Wang H, Long Q. Inhalation of MSC-EVs is a noninvasive strategy for ameliorating acute lung injury. J Control Release. 2022;345:214-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu B, Gan CX, Chen SS, Li JQ, Liu MZ, Guo GH. BMSC-derived exosomes alleviate smoke inhalation lung injury through blockade of the HMGB1/NF-κB pathway. Life Sci. 2020;257:118042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liang Y, Yin C, Lu X, Jiang H, Jin F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells protect lungs from smoke inhalation injury by differentiating into alveolar epithelial cells via Notch signaling. J Biosci. 2019;44:2. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li F, Zhang F, Wang T, Xie Z, Luo H, Dong W, Zhang J, Ren C, Peng W. A self-amplifying loop of TP53INP1 and P53 drives oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Apoptosis. 2024;29:882-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Debnath J, Gammoh N, Ryan KM. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:560-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 317.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vargas JNS, Hamasaki M, Kawabata T, Youle RJ, Yoshimori T. The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy in mammals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 246.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen Y, Li S, Zhang Y, Wang M, Li X, Liu S, Xu D, Bao Y, Jia P, Wu N, Lu Y, Jia D. The lncRNA Malat1 regulates microvascular function after myocardial infarction in mice via miR-26b-5p/Mfn1 axis-mediated mitochondrial dynamics. Redox Biol. 2021;41:101910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Park EG, Pyo SJ, Cui Y, Yoon SH, Nam JW. Tumor immune microenvironment lncRNAs. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23:bbab504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ashrafizadeh M, Rabiee N, Kumar AP, Sethi G, Zarrabi A, Wang Y. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in pancreatic cancer progression. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27:2181-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zuo Z, Liu L, Song B, Tan J, Ding D, Lu Y. Silencing of Long Non-coding RNA ENST00000606790.1 Inhibits the Malignant Behaviors of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma through the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Endocr Res. 2021;46:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Luo NQ, Ma DR, Yang XC, Liu Y, Zhou P, Guo LJ, Huang XD. Long non-coding RNA ENST00000434223 inhibits the progression of renal cancer through Wnt/hygro-catenin signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:6868-6877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4127] [Cited by in RCA: 5525] [Article Influence: 394.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Orso F, Virga F, Dettori D, Dalmasso A, Paradzik M, Savino A, Pomatto MAC, Quirico L, Cucinelli S, Coco M, Mareschi K, Fagioli F, Salmena L, Camussi G, Provero P, Poli V, Mazzone M, Pandolfi PP, Taverna D. Stroma-derived miR-214 coordinates tumor dissemination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Winkle M, van den Berg A, Tayari M, Sietzema J, Terpstra M, Kortman G, de Jong D, Visser L, Diepstra A, Kok K, Kluiver J. Long noncoding RNAs as a novel component of the Myc transcriptional network. FASEB J. 2015;29:2338-2346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zeng C, Liu S, Lu S, Yu X, Lai J, Wu Y, Chen S, Wang L, Yu Z, Luo G, Li Y. The c-Myc-regulated lncRNA NEAT1 and paraspeckles modulate imatinib-induced apoptosis in CML cells. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang K. Autophagy and apoptosis in liver injury. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:1631-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bridges MC, Daulagala AC, Kourtidis A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. J Cell Biol. 2021;220:e202009045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 940] [Article Influence: 235.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Herman AB, Tsitsipatis D, Gorospe M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol Cell. 2022;82:2252-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nojima T, Proudfoot NJ. Mechanisms of lncRNA biogenesis as revealed by nascent transcriptomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:389-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 83.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ye M, Fang Y, Chen L, Song Z, Bao Q, Wang F, Huang H, Xu J, Wang Z, Xiao R, Han M, Gao S, Liu H, Jiang B, Qing G. Therapeutic targeting nudix hydrolase 1 creates a MYC-driven metabolic vulnerability. Nat Commun. 2024;15:2377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang X, Li S, Malik I, Do MH, Ji L, Chou C, Shi W, Capistrano KJ, Zhang J, Hsu TW, Nixon BG, Xu K, Wang X, Ballabio A, Schmidt LS, Linehan WM, Li MO. Reprogramming tumour-associated macrophages to outcompete cancer cells. Nature. 2023;619:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Casey SC, Baylot V, Felsher DW. The MYC oncogene is a global regulator of the immune response. Blood. 2018;131:2007-2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Karreth FA, Tay Y, Perna D, Ala U, Tan SM, Rust AG, DeNicola G, Webster KA, Weiss D, Perez-Mancera PA, Krauthammer M, Halaban R, Provero P, Adams DJ, Tuveson DA, Pandolfi PP. In vivo identification of tumor- suppressive PTEN ceRNAs in an oncogenic BRAF-induced mouse model of melanoma. Cell. 2011;147:382-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tay Y, Kats L, Salmena L, Weiss D, Tan SM, Ala U, Karreth F, Poliseno L, Provero P, Di Cunto F, Lieberman J, Rigoutsos I, Pandolfi PP. Coding-independent regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by competing endogenous mRNAs. Cell. 2011;147:344-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 772] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 60.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang L, Cho KB, Li Y, Tao G, Xie Z, Guo B. Long Noncoding RNA (lncRNA)-Mediated Competing Endogenous RNA Networks Provide Novel Potential Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | di Iasio MG, Norcio A, Melloni E, Zauli G. SOCS1 is significantly up-regulated in Nutlin-3-treated p53wild-type B chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) samples and shows an inverse correlation with miR-155. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:2403-2406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Piao L, Huang Z, Inoue A, Kuzuya M, Cheng XW. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate aging-associated skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction by modulating apoptosis and mitochondrial damage in SAMP10 mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang M, Cui Y, Song J, Cui C, Wang L, Liang K, Wang C, Sha S, He Q, Hu H, Guo X, Zang N, Sun L, Chen L. Mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improved mitochondrial function and alleviated inflammation and apoptosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating SIRT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;546:74-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Peña-Blanco A, García-Sáez AJ. Bax, Bak and beyond - mitochondrial performance in apoptosis. FEBS J. 2018;285:416-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 633] [Article Influence: 79.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Karch J, Kwong JQ, Burr AR, Sargent MA, Elrod JW, Peixoto PM, Martinez-Caballero S, Osinska H, Cheng EH, Robbins J, Kinnally KW, Molkentin JD. Bax and Bak function as the outer membrane component of the mitochondrial permeability pore in regulating necrotic cell death in mice. Elife. 2013;2:e00772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Victorelli S, Salmonowicz H, Chapman J, Martini H, Vizioli MG, Riley JS, Cloix C, Hall-Younger E, Machado Espindola-Netto J, Jurk D, Lagnado AB, Sales Gomez L, Farr JN, Saul D, Reed R, Kelly G, Eppard M, Greaves LC, Dou Z, Pirius N, Szczepanowska K, Porritt RA, Huang H, Huang TY, Mann DA, Masuda CA, Khosla S, Dai H, Kaufmann SH, Zacharioudakis E, Gavathiotis E, LeBrasseur NK, Lei X, Sainz AG, Korolchuk VI, Adams PD, Shadel GS, Tait SWG, Passos JF. Apoptotic stress causes mtDNA release during senescence and drives the SASP. Nature. 2023;622:627-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 128.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chen Y, Zhang Y, Li N, Jiang Z, Li X. Role of mitochondrial stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome in lung diseases. Inflamm Res. 2023;72:829-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |