Published online Jan 26, 2021. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i1.128

Peer-review started: September 1, 2020

First decision: September 15, 2020

Revised: November 1, 2020

Accepted: November 17, 2020

Article in press: November 17, 2020

Published online: January 26, 2021

Processing time: 142 Days and 0.1 Hours

Multipotent bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) are adult stem cells that form functional osteoblasts and play a critical role in bone remodeling. During aging, an increase in bone loss and reduction in structural integrity lead to osteoporosis and result in an increased risk of fracture. We examined age-dependent histological changes in murine vertebrae and uncovered that bone loss begins as early as the age of 1 mo.

To identify the functional alterations and transcriptomic dynamics of BMSCs during early bone loss.

We collected BMSCs from mice at early to middle ages and compared their self-renewal and differentiation potential. Subsequently, we obtained the transcriptomic profiles of BMSCs at 1 mo, 3 mo, and 7 mo.

The colony-forming and osteogenic commitment capacity showed a comparable finding that decreased at the age of 1 mo. The transcriptomic analysis showed the enrichment of osteoblastic regulation genes at 1 mo and loss of osteogenic features at 3 mo. The BMSCs at 7 mo showed enrichment of adipogenic and DNA repair features. Moreover, we demonstrated that the WNT and MAPK signaling pathways were upregulated at 1 mo, followed by increased pro-inflammatory and apoptotic features.

Our study uncovered the cellular and molecular dynamics of bone aging in mice and demonstrated the contribution of BMSCs to the early stage of age-related bone loss.

Core Tip: Multipotent bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) are adult stem cells that form functional osteoblasts and play a critical role in bone remodeling. During aging, an increase in bone loss and reduction in structural integrity lead to osteoporosis and result in an increased risk of fracture. In this study, we examined age-dependent histological changes in murine vertebrae and uncovered that bone loss begins as early as the age of 1 mo. The BMSCs isolated at different ages revealed a consistent decreasing trend in both colony-forming and osteogenic commitment capacity. Moreover, we obtained the transcriptomic profiles of BMSCs at 1 mo, 3 mo, and 7 mo to investigate the distinct molecular and regulatory features that underpin the early loss of osteogenic potential. We showed the enrichment of osteoblastic regulation genes at 1 mo and loss of osteogenic features at 3 mo. The adipogenic and DNA repair features were enriched in the later age at 7 mo. Moreover, we demonstrated that the WNT and MAPK signaling pathways were upregulated at 1 mo, followed by increased pro-inflammatory and apoptotic features.

- Citation: Cheng YH, Liu SF, Dong JC, Bian Q. Transcriptomic alterations underline aging of osteogenic bone marrow stromal cells. World J Stem Cells 2021; 13(1): 128-138

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v13/i1/128.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v13.i1.128

Multipotent bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) are adult stem cells that can be isolated through plastic adherence and differentiate into three distinct lineages, including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes in vitro. BMSCs are responsible for constant renewal and generate functional osteoblasts in vivo that work with bone-resorbing osteoclasts to remodel bone structure[1]. It is well-known that an increase in bone loss with age leads to a more fragile skeletal integrity and causes osteoporosis[2,3]. In mice, the size of cortical bone, trabecular bone volume, and bone strength reach the peak at 3 mo followed by a constant decline[4,5]. In humans, bone mineral density peaks at the age of early 20 s and declines with age advancing[6,7]. Despite much scrutiny in age-dependent bone loss, the causal relationship between BMSCs and age-dependent bone loss is inferred mainly from the osteogenic features of BMSCs. There are limited studies about the role of multipotent BMSCs in bone aging. A study examined age-dependent changes in the number and lineage potential of multipotent BMSCs between the age of 3 mo and 24 mo and revealed that the self-renewal and osteogenic potential of BMSCs reached peaks at 3 mo and then decreased, which is consistent with the phenotypic features observed[8].

With the recent advances in microarray and sequencing technology, identification of the molecular features and dynamics of multipotent BMSCs in an unbiased manner has become possible. From the global transcriptome analysis, BMSCs showed an upregulation of genes that encode extracellular matrix components compared with other stem cells and mature cell types. Besides, BMSCs also present distinct transcriptomic signatures of mobility, proliferation, and oxidative stress response[9]. Aside from functional molecular features, the transcriptome comparison across time of human BMSCs identified 155 genes associated with BMSCs aging in vitro[10]. A recent study isolated two distinct BMSC populations, the CXCL12-abundant reticular cells and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-a+Sca1+ cells. The comparison of transcriptomes between BMSCs isolated at 2 wk, 2 mo, and 2 years revealed the upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression that is associated

To identify the detailed dynamics of bone loss, we conducted a temporal observation of murine vertebrae at different time points, focusing on the early to middle age, and subsequently uncovered the molecular dynamics that underpin BMSC aging by global transcriptome analysis.

Male imprinting control region mice (n = 10 per time point) were obtained from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center (SCXK 2007-0005, Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality). The study was approved by the Shanghai Animal Ethics Committee.

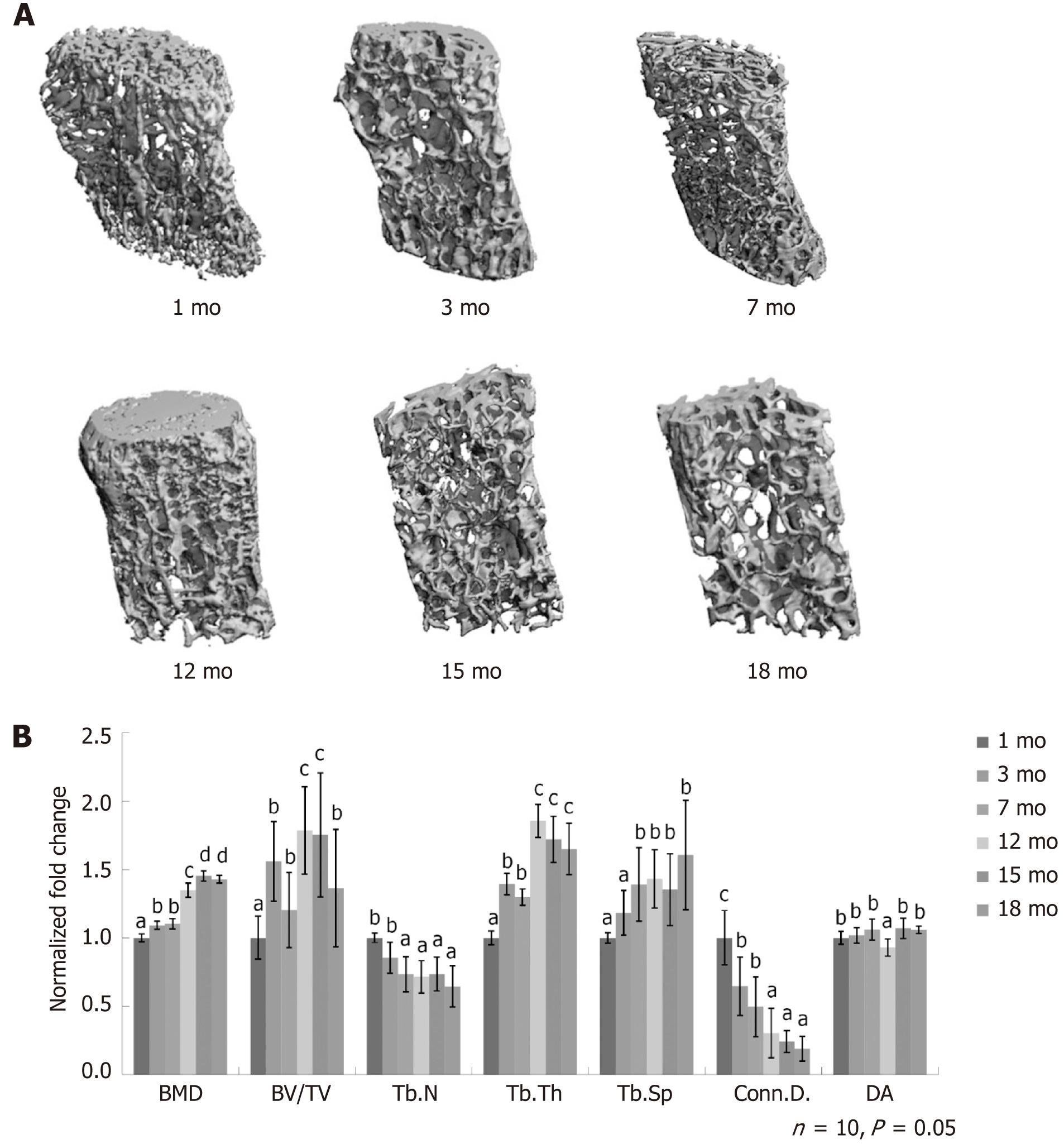

Lumbar spine specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, washed for 2 h, and examined. L4 vertebrae in each group were subjected to a 3D model without adnexa, the transverse, and the spinous processes. The images were captured using µCT 80 radiograph microtomography (Scanco Medical AG, Switzerland), and further processed with 3DCalc, cone reconstruction, and AVG model building software (HP, Japan). The bitmap data set was employed to reconstruct the 3D model. Scores for the bone mass density (BMD), the ratio of bone volume to tissue volume (BV/TV), the connectivity density of trabeculae (Conn.D.), the trabecular number (Tb.N), the trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and the trabecular spaces (Tb.Sp) were measured from the 3D model.

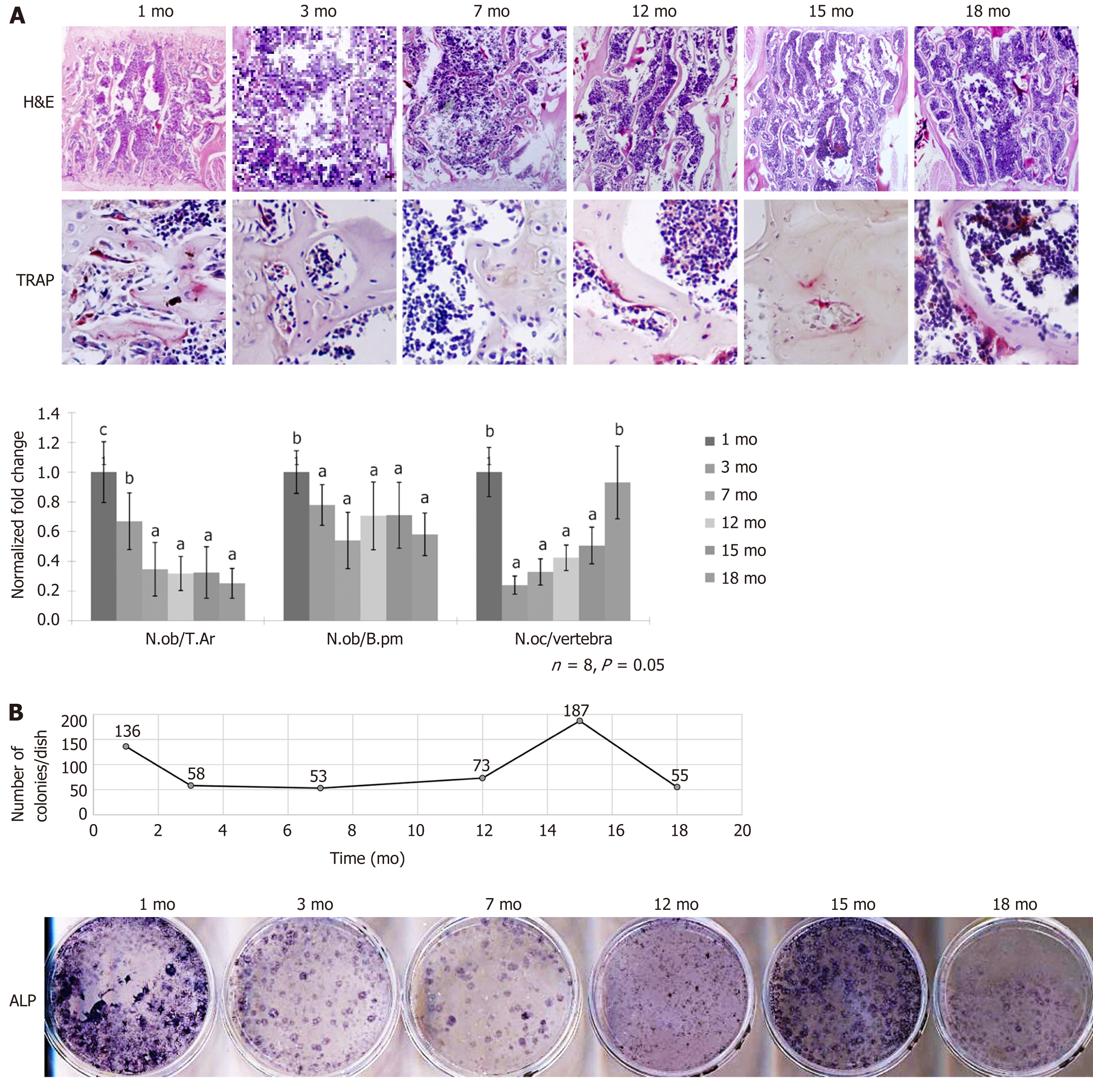

Lumbar spines from the mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, decalcified in 10% EDTA for 4 wk, and embedded in paraffin wax. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or underwent the following tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining (Sigma-Aldrich). The morphometric analysis was performed with an image auto-analysis system (Olympus BX50; Japan). The static parameters, including trabecular bone area (T.Ar) and the bone perimeter (B.Pm), were collected from the L4 lumbar spine and applied to compute the bone remodeling parameters, which include the osteoblast formation (N.ob/T.Ar, N.ob/B.pm) and the number of the osteoclast (N.oc/B.pm).

BMSCs were obtained from the bone marrow aspiration of the bilateral tibia and femur. The cells were further subjected to either colony-forming assay, differentiation assay, or microarray detection. The marrow cavity was flushed with α-MEM (Gibco, United States) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, United States) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, United States). The cells were cultured and expanded in 10 cm dishes (2 mice per dish) for 7 d for microarray detection. The number of colony-forming unit-fibroblasts (CFU-F) was counted under an inverted light microscope on the 3rd day of culture. For alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with nitro blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Pierce, United States) for 30 min.

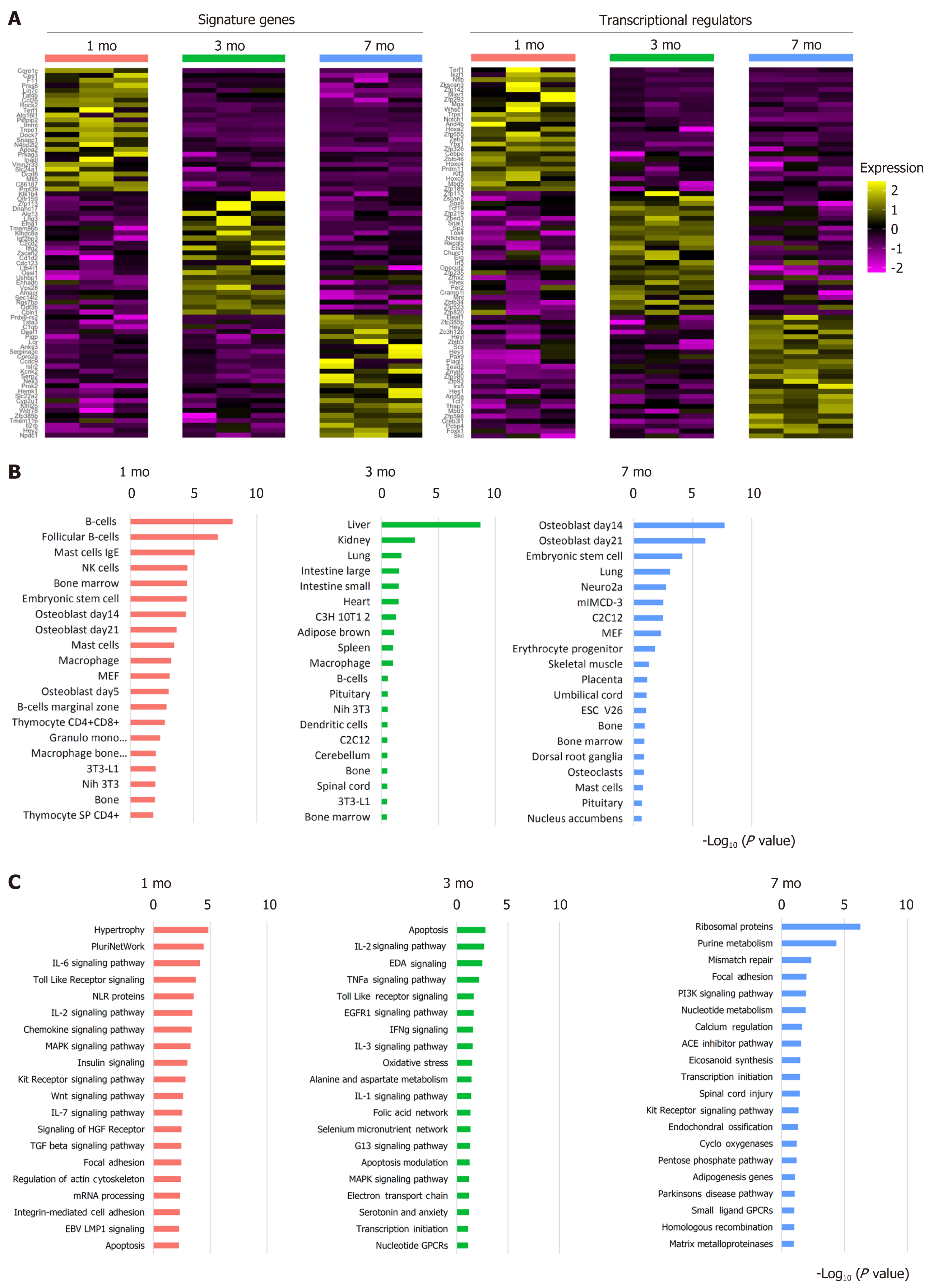

The transcriptomic profiles were captured using NimbleGen gene expression profiling (No. PXH100525) containing 26991 genes (3 pieces per group, n = 9). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions, including the DNase digestion step. After quality control via RNA measurement on the Nanodrop ND-1000 and denaturing gel electrophoresis, the samples were amplified and labeled using a NimbleGen one-color DNA labeling kit and hybridized in the NimbleGen hybridization system. Subsequently, the chip underwent steps of washing and scanned with the Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner. Raw data were obtained with NimbleScan software (version 2.5). NimbleScan software’s implementation of RMA offers quantile normalization and background correction. The gene summary files were imported into Agilent GeneSpring software (version11.0) for further analysis. Differentially expressed genes were identified through fold-change and t-test screening and visualized via the heatmap function of the Seurat package in R[12].

We used the R package enrichR to complete the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). The top enriched markers of each group were extracted and subjected to enrichR function. The mouse cell atlas database was used to characterize the cell typing features of samples, and the Wikipathway 2019 Mouse database was used to analyze the most enriched pathways features.

The data are expressed as the mean ± SE, and statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s test (heterogeneity of variance) using aov and TukeyHSD function in R. The significance level was defined at P < 0.05.

We applied µCT imaging to quantitatively measure the densitometry and capture the structural dynamics in lumbar spines at multiple time points. We combined the imaging findings with histological features to quantitatively analyze the dynamic changes of osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone tissue. Subsequently, we isolated BMSCs and characterized their self-renewal and osteogenic potential to support the imaging and histological findings. Finally, we identified the molecular signatures that underpin the bone loss by obtaining the gene expression profile near the initiation time point when BMSCs lose self-renewal and differentiation potential.

We obtained the µCT three-dimensional images of the L4 lumbar spine from mice at the age of 1 mo, 3 mo, 7 mo, 12 mo, 15 mo, and 18 mo. The loss of bone volume and decrease in connectedness in the cancellous compartment with age were apparent (Figure 1A). The quantitative analysis revealed the changes in the cancellous bone integrity with age. The BMD continuously increased and plateaued at 15 mo with a 45% increase, and later remained constant. The BV/TV varied across the time and peaked at 12 mo with a 75% increase, followed by a dramatic decrease at 18 mo. For trabecular bone, the Tb.N decreased over time, but the difference between 7 and 18 mo was not significant. Between 1 and 18 mo, Tb.N decreased by 36%. The Tb.Th continuously increased and reached the plateau at 12 mo. The Tb.Sp increased from 1 to 18 mo by 60%. The Conn.D. decreased from 1 to 12 mo, while beyond the age of 12 mo, the Conn.D. remained constant. The degree of anisotropy in trabecular bone orientation stayed the same with age (Figure 1B). The finding that the trabeculae number decreased along with the increase in BMD with age indicated the enhancement of mineral deposit and active bone remodeling. The decrease in cancellous bone volume and trabecular thickness from 12 mo suggested that bone remodeling reached the equilibrium of formation and resorption at 12 mo and later skewed to the resorption.

To investigate the cellular composition with age, we performed histological analysis on the L4 lumbar trabecular bone at 1 mo, 3 mo, 7 mo, 12 mo, 15 mo, and 18 mo. In the aged 18-mo-old mice, we observed bone structure reduction and a lower density of osteoblasts. Across the age followed, the number of osteoblasts per trabecular area (T.Ar) maintained at a relatively high level until 3 mo, followed by a drop, and then remained constant with advancing age. The difference was similar to the results normalized by bone perimeter (B.pm). On the bone resorption side, the osteoclast number per vertebra peaked at 1 mo with a sharp drop and gradually returned to a similar level at the age of 18 mo (Figure 2A).

To determine the self-renewal and differentiation features of BMSCs, we flushed bone marrow cells from 1 mo, 3 mo, 7 mo, 12 mo, 15 mo, and 18-mo-old mice and performed CFU-F and ALP staining assays. The number of colonies decreased at 3 mo and began to increase from the age of 12 mo. The self-renewal capacity reached a peak at 15 mo, followed by a sharp decrease at 18 mo. To study whether aging alters the osteogenic potential of BMSCs, we examined the ALP activity via staining. The results showed that ALP activity reached two peaks at 1 and 15 mo, which represented the modeling and the remodeling phase during development and aging (Figure 2B). The results suggested that the self-renewal and differentiation potential of BMSCs dropped during the modeling phase, followed by an increase at the middle age between 12 and 15 mo. After that, the capacity again dropped sharply at 18 mo.

We collected the transcriptome profiles of BMSCs via microarray at the age of 1 mo, 3 mo, and 7 mo to uncover the molecular regulation contributing to the drop of self-renewal and differentiation potential observed in 1-mo-old mice. The feature signatures at 1 mo included genes associated with mesenchymal migration, such as Coro1c, and telomere regulation, such as Terf1. Some critical osteoblastic regulation genes, such as Tnpo1, Dock7, and Apoa2 were also enriched at an early age. Multiple Hox genes were relatively enriched at the age of 1 mo, suggesting the involvement of patterning of the bone tissue. At 3 mo, the BMSCs did not show the osteogenic regulation and distinct aging-preventing features that enriched in 1 mo but showed enrichment of chondrogenic regulators Sox9 and Snai1. BMSCs also gained the osteoblastic inhibition and osteoclast promoting feature gene Efna1. The BMSCs at 7 mo showed enrichment of the bone remodeling regulators Hey1 and Hey2. We also observed enhanced expression of DNA repair gene Neil3 (Figure 3A).

Subsequently, we subjected the differential genes to the GSEA analysis. Using the cell atlas database, we uncovered that 1-mo and 7-mo samples were relatively enriched in osteoblasts and bone features, but lost of the osteogenic features at 3 mo (Figure 3B). When we applied the pathway analysis database as a reference, we uncovered the underlying signaling pathways that were involved in gaining distinct features. At 1 mo, the MAPK and WNT signaling pathways were highly enriched. The 3-mo sample presented pathways related to apoptosis, stress features, and more pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, including IL-1 and IFNg signaling pathways. At the age of 7 mo, the pathway related to adipogenesis began to appear, and also present features of DNA repair. High enrichment of both ossification and matrix metalloproteinase resorption pathways suggested active bone remodeling (Figure 3C).

Bone loss is a specific feature during aging that is partially caused by the impaired osteogenic capacity of BMSCs. In this study, we characterized bone and BMSC features in mice at different ages and uncovered the underlying transcriptomic changes. The µCT results revealed the dynamic alteration in murine vertebrae during aging. The finding was similar to the previous study that observed the age-related changes in the long bone tibia[13]. Although both vertebrae and long bone showed a constantly decreased trabecular number, the bone volume and trabecular thickness in vertebrae fluctuated, which increased at an early age followed by constant downward trend. The pattern of changes in mouse vertebrae was also similar to that observed in humans. In both species, the BV/TV and Tb.N in lumbar vertebrae increased at an early age during growth and development followed by a downward trend with age[14,15]. However, there was a difference between the trabecular bone of humans and mice. In humans, Tb.Th presents finer alterations that showed both thinner trabecula and thickening remaining trabecula, which did lead to overall significant changes with age[16]. In mice, the thinness of trabecular bones was significantly increased at an early age and remained constant after the age of 7 mo. The temporal changes in bone with age were surprisingly similar between mice and humans. The total bone mass peaks at midlife around 30 and 40 years of age in humans while the bone mass in mice also peaks at the middle age of 15 mo[17].

The cellular components in the bone remodeling of mouse vertebrae changed with age. The decreasing density of bone-forming osteoblasts and the increasing number of osteoclasts were consistent with the previous reports that the activity of bone formation decreased while bone resorption increased with age[18,19]. However, we noticed a peak in the number of osteoclasts at an early age, which suggested the early activation of bone modeling. Unlike osteoblasts, the stem and progenitor populations BMSCs that are responsible for bone repopulation showed a different pattern of changes with age. Considering both self-renewal colony-forming assay and osteogenic assessment, a similar peak presented at the early life at 1 mo, which was consistent with the high osteoblast density as we observed; however, we observed a significant increase in the amount of colony formation with high osteoblastic features at 15 mo. The previous study assessed the number and differentiation potential of BMSCs between the ages of 3 mo and 18 mo also reported a similar pattern[8]. The discrepancy between a high osteogenic capacity and a low number of osteoblasts could be related to the high bone remodeling at the age of 15 mo and exertion of the BMSC populations. However, the other study isolated BMSCs from rats of 1 mo and 16 mo of age did not uncover a similar pattern. The BMSCs from the 16-mo-old rats had significantly decreased colony number, size, and ALP expression compared with the 3-wk-old rats[20]. The difference suggested that the transient recovering capacity of BMSCs might vary across species and require a finer follow-up interval to uncover.

We obtained the transcriptomic profile of BMSCs at the early time points to investigate the underlying molecular regulation that underpins the early decrease in BMSC capacity. At the age of 1 mo, the BMSCs showed multiple feature genes related to osteogenic regulation, including Tnpo1, Dock7, and Apoa2. A previous study showed that knockdown of Tnpo1 via siRNA abrogated the osteoblast differentiation of BMSCs[21]. The other study reported that Dock7 was responsible for trabecular maintenance. Loss of Dock7 in the mice resulted in an impairment of periosteal and endocortical envelope expansion and lower trabecular bone mass[22]. A recent study uncovered that Apoa2 knockout mice derived BMSCs had a less osteogenic commitment and an increased tendency to form adipocytes[23]. Aside from osteogenic regulation, the top differential genes also uncovered general features that were distinct in early life. Terf1 is the gene that was correlated to telomere maintenance in stem cell populations and was highly associated with aging[24,25]. Terf1 was also highly enriched at the age of 1 mo compared with the other two time points. The finding was consistent with the fact that the sample was the youngest among the others. Unlike the osteogenic related features, the 3-mo data revealed more differential genes that are related to chondrogenic commitment including Snai1 and Sox9. Sox9 is a well-known master regulator that governs chondrogenic commitment[26]. A previous study of Snai1 knockout showed a substantial defect in the long bones[27]. The chondrogenic features along with the endochondral ossification features in the following time point suggested a temporal progression of bone growth and development. The BMSCs of the later age of 7 mo revealed features of aging and bone resorption. Neil3, one of the top differential genes, is involved in DNA repair, which is one of the critical factors related to genome stability and cellular aging[28,29]. The other feature gene Efna1 was reported to promote osteoclastogenesis and inhibit osteoblast formation, suggesting the tendency of enhanced bone resorption[30,31].

The following GSEA of the differential genes allowed us to have a broader picture of the feature genes at different ages. When we applied the cell atlas database to be the reference, BMSCs from mice aged 1 mo or 7 mo revealed the enrichment of osteoblast features, while BMSCs from mice at the age of 3 mo showed a more diverse cell type feature. The loss of the osteogenic features at 3 mo was temporally consistent with our findings of a drastic decrease in the osteogenic capacity of BMSCs. The GSEA using the signaling-pathway database as a reference also supported the findings. The pathways involved at 1 mo were largely related to osteogenic regulation, including WNT and MAPK pathways[32,33]. At 3 mo, the signaling pathways revealed more pro-inflammatory features, including IL-1 and IFNg signaling pathways. The most significant apoptotic pathways suggested the bone loss as we observed at an early stage, which was probably caused by the activation of apoptosis in BMSCs, and ultimately contributed to the remodeling of the bone architecture. The pathways involved in BMSCs at the later age of 7 mo were related to DNA mismatch repair and bone remodeling, which included ossification and MMP enzymes. The finding was consistent with the top enriched genes discovered at a later age.

In summary, our study showed the histological and cellular dynamics of bone aging in mice and demonstrated the temporal changes of the osteogenic BMSCs. Moreover, we uncovered the temporal features via transcriptomic analysis, which suggested the contribution of BMSCs to the early stage of age-related bone loss.

Multipotent bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) form functional osteoblasts and are involved in bone formation. During aging, significant bone loss leads to osteoporosis and results in an increased risk of fracture.

We discovered that an early bone loss occurs as early as 1 mo in mice, and we would like to investigate the role of BMSCs during early bone loss.

To understand the functional alterations of BMSCs during the early bone loss and uncover the transcriptomic dynamics that underpin the early loss of osteogenic potential.

We collected BMSCs from mice at early to middle ages and assessed their self-renewal and differentiation potential. Subsequently, we obtained the transcriptomic profiles at a young age to reveal the features of BMSCs during early bone loss.

The colony-forming and osteogenic commitment capacity decreased at the age of 1 mo. At 3 mo, BMSCs were enriched in osteoblastic regulation genes, and at 7 mo, the transcriptomic features shifted toward adipogenic and DNA repair. The gene set enrichment analysis suggested the involvement of WNT and MAPK signaling pathways at the osteogenic phase and increased pro-inflammatory and apoptotic features at the latter phase.

We demonstrated the contribution of BMSCs to the early stage of age-related bone loss and uncovered the underlying transcriptomic dynamics.

Resolving the detailed cellular and molecular mechanism underlying bone aging is crucial. In this study, we demonstrated the role of BMSCs in early bone loss and revealed the transcriptomic dynamics to better understand the underlying molecular mechanism.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cell biology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Greenberger J S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2250-2261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1422] [Cited by in RCA: 1364] [Article Influence: 71.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zaidi M. Skeletal remodeling in health and disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:791-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 806] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Compston JE, McClung MR, Leslie WD. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2019;393:364-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 866] [Cited by in RCA: 1463] [Article Influence: 243.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ramanadham S, Yarasheski KE, Silva MJ, Wohltmann M, Novack DV, Christiansen B, Tu X, Zhang S, Lei X, Turk J. Age-related changes in bone morphology are accelerated in group VIA phospholipase A2 (iPLA2beta)-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:868-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawashima Y, Fritton JC, Yakar S, Epstein S, Schaffler MB, Jepsen KJ, LeRoith D. Type 2 diabetic mice demonstrate slender long bones with increased fragility secondary to increased osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 2009;44:648-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kralick AE, Zemel BS. Evolutionary Perspectives on the Developing Skeleton and Implications for Lifelong Health. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Russo CR, Lauretani F, Seeman E, Bartali B, Bandinelli S, Di Iorio A, Guralnik J, Ferrucci L. Structural adaptations to bone loss in aging men and women. Bone. 2006;38:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang W, Ou G, Hamrick M, Hill W, Borke J, Wenger K, Chutkan N, Yu J, Mi QS, Isales CM, Shi XM. Age-related changes in the osteogenic differentiation potential of mouse bone marrow stromal cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1118-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ren J, Jin P, Sabatino M, Balakumaran A, Feng J, Kuznetsov SA, Klein HG, Robey PG, Stroncek DF. Global transcriptome analysis of human bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) reveals proliferative, mobile and interactive cells that produce abundant extracellular matrix proteins, some of which may affect BMSC potency. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:661-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ren J, Stroncek DF, Zhao Y, Jin P, Castiello L, Civini S, Wang H, Feng J, Tran K, Kuznetsov SA, Robey PG, Sabatino M. Intra-subject variability in human bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) replicative senescence: molecular changes associated with BMSC senescence. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11:1060-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Helbling PM, Piñeiro-Yáñez E, Gerosa R, Boettcher S, Al-Shahrour F, Manz MG, Nombela-Arrieta C. Global Transcriptomic Profiling of the Bone Marrow Stromal Microenvironment during Postnatal Development, Aging, and Inflammation. Cell Rep 2019; 29: 3313-3330. e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:411-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7652] [Cited by in RCA: 7843] [Article Influence: 1120.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Halloran BP, Ferguson VL, Simske SJ, Burghardt A, Venton LL, Majumdar S. Changes in bone structure and mass with advancing age in the male C57BL/6J mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17: 1044-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Acquaah F, Robson Brown KA, Ahmed F, Jeffery N, Abel RL. Early Trabecular Development in Human Vertebrae: Overproduction, Constructive Regression, and Refinement. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2015;6:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen H, Zhou X, Fujita H, Onozuka M, Kubo KY. Age-related changes in trabecular and cortical bone microstructure. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:213234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen H, Shoumura S, Emura S, Bunai Y. Regional variations of vertebral trabecular bone microstructure with age and gender. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1473-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bar-Shira-Maymon B, Coleman R, Cohen A, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Silbermann M. Age-related bone loss in lumbar vertebrae of CW-1 female mice: a histomorphometric study. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;44:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chung PL, Zhou S, Eslami B, Shen L, LeBoff MS, Glowacki J. Effect of age on regulation of human osteoclast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1412-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Becerikli M, Jaurich H, Schira J, Schulte M, Döbele C, Wallner C, Abraham S, Wagner JM, Dadras M, Kneser U, Lehnhardt M, Behr B. Age-dependent alterations in osteoblast and osteoclast activity in human cancellous bone. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2773-2781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stolzing A, Scutt A. Age-related impairment of mesenchymal progenitor cell function. Aging Cell. 2006;5:213-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Di Benedetto A, Sun L, Zambonin CG, Tamma R, Nico B, Calvano CD, Colaianni G, Ji Y, Mori G, Grano M, Lu P, Colucci S, Yuen T, New MI, Zallone A, Zaidi M. Osteoblast regulation via ligand-activated nuclear trafficking of the oxytocin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16502-16507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Le PT, Bishop KA, Maridas DE, Motyl KJ, Brooks DJ, Nagano K, Baron R, Bouxsein ML, Rosen CJ. Spontaneous mutation of Dock7 results in lower trabecular bone mass and impaired periosteal expansion in aged female Misty mice. Bone. 2017;105:103-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Blair HC, Kalyvioti E, Papachristou NI, Tourkova IL, Syggelos SA, Deligianni D, Orkoula MG, Kontoyannis CG, Karavia EA, Kypreos KE, Papachristou DJ. Apolipoprotein A-1 regulates osteoblast and lipoblast precursor cells in mice. Lab Invest. 2016;96:763-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schneider RP, Garrobo I, Foronda M, Palacios JA, Marión RM, Flores I, Ortega S, Blasco MA. TRF1 is a stem cell marker and is essential for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lisaingo K, Uringa EJ, Lansdorp PM. Resolution of telomere associations by TRF1 cleavage in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1958-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wright E, Hargrave MR, Christiansen J, Cooper L, Kun J, Evans T, Gangadharan U, Greenfield A, Koopman P. The Sry-related gene Sox9 is expressed during chondrogenesis in mouse embryos. Nat Genet. 1995;9:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 503] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen Y, Gridley T. Compensatory regulation of the Snai1 and Snai2 genes during chondrogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1412-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhou J, Chan J, Lambelé M, Yusufzai T, Stumpff J, Opresko PL, Thali M, Wallace SS. NEIL3 Repairs Telomere Damage during S Phase to Secure Chromosome Segregation at Mitosis. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2044-2056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lombard DB, Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Franco S, Gostissa M, Alt FW. DNA repair, genome stability, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:497-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Irie N, Takada Y, Watanabe Y, Matsuzaki Y, Naruse C, Asano M, Iwakura Y, Suda T, Matsuo K. Bidirectional signaling through ephrinA2-EphA2 enhances osteoclastogenesis and suppresses osteoblastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14637-14644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zanotti S, Canalis E. Hairy and Enhancer of Split-related with YRPW motif (HEY)2 regulates bone remodeling in mice. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:21547-21557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jia M, Chen S, Zhang B, Liang H, Feng J, Zong Z. Effects of constitutive β-catenin activation on vertebral bone growth and remodeling at different postnatal stages in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rodríguez-Carballo E, Gámez B, Ventura F. p38 MAPK Signaling in Osteoblast Differentiation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016;4:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |