Published online Jul 26, 2020. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i7.621

Peer-review started: February 28, 2020

First decision: April 18, 2020

Revised: May 19, 2020

Accepted: June 10, 2020

Article in press: June 10, 2020

Published online: July 26, 2020

Processing time: 148 Days and 10.1 Hours

Advanced glycation end products (AGE) are a marker of various diseases including diabetes, in which they participate to vascular damages such as retinopathy, nephropathy and coronaropathy. Besides those vascular complications, AGE are involved in altered metabolism in many tissues, including adipose tissue (AT) where they contribute to reduced glucose uptake and attenuation of insulin sensitivity. AGE are known to contribute to type 1 diabetes (T1D) through promotion of interleukin (IL)-17 secreting T helper (Th17) cells.

To investigate whether lean adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) could be able to induce IL-17A secretion, with the help of AGE.

As we have recently demonstrated that ASC are involved in Th17 cell promotion when they are harvested from obese AT, we used the same co-culture model to measure the impact of glycated human serum albumin (G-HSA) on human lean ASC interacting with blood mononuclear cells. IL-17A and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion were measured by ELISA. Receptor of AGE (RAGE) together with intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), human leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-DR, cluster of differentiation (CD) 41, and CD62P surface expressions were measured by cytofluorometry. Anti-RAGE specific monoclonal antibody was added to co-cultures in order to evaluate the role of RAGE in IL-17A production.

Results showed that whereas 1% G-HSA only weakly potentiated the production of IL-17A by T cells interacting with ASC harvested from obese subjects, it markedly increased IL-17A, but also interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha production in the presence of ASC harvested from lean individuals. This was associated with increased expression of RAGE and HLA-DR molecule by co-cultured cells. Moreover, RAGE blockade experiments demonstrated RAGE specific involvement in lean ASC-mediated Th-17 cell activation. Finally, platelet aggregation and ICAM-1, which are known to be induced by AGE, were not involved in these processes.

Thus, our results demonstrated that G-HSA potentiated lean ASC-mediated IL-17A production in AT, suggesting a new mechanism by which AGE could contribute to T1D pathophysiology.

Core tip: Using a coculture model with human lean adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) and mononuclear cells, we have shown in this study that glycated human serum albumin (G-HSA) enhances lean ASC-mediated interleukin (IL)-17A, interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion. This effect involved the advanced glycated end products (AGE)/Receptor of advanced glycated end products (RAGE) axis as assessed by anti-RAGE blocking antibodies and was associated with increased expression of RAGE and human leukocyte antigen-DR molecules. Thus, our results demonstrated that G-HSA potentiated lean ASC-mediated IL-17A production in adipose tissues, suggesting a new mechanism by which AGE could contribute to type 1 diabetes pathophysiology.

- Citation: Pestel J, Robert M, Corbin S, Vidal H, Eljaafari A. Involvement of glycated albumin in adipose-derived-stem cell-mediated interleukin 17 secreting T helper cell activation. World J Stem Cells 2020; 12(7): 621-632

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v12/i7/621.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v12.i7.621

Glycated proteins result from non-enzymatic Maillard reactions between sugars and amine residues, mostly lysine and arginine[1]. While in the healthy body all proteins can be modified by non-enzymatic glycation reactions, advanced glycation end products (AGE) are known to exert deleterious effects on human health when they are too abundant, as observed in diabetes, arteriosclerosis, renal failure and also in Alzheimer, and Parkinson diseases[2-4]. Although glycated haemoglobin is a major biomarker for diabetes mellitus diagnosis[5], the role of glycated albumin as a potential diagnostic marker[6] is currently under investigation, due to the higher levels of albumin in blood, its shorter life, and its independence from haemolytic processes[7-9]. In addition to modifications of protein structure and function, AGE pathogenic effects mostly result from binding and activation of specific receptors, named receptor of advanced glycated end products (RAGE)[10,11]. Those receptors belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily of transmembrane proteins[12]. Besides AGE, RAGE can bind a variety of molecules, such as the high mobility group box-1, the β-amyloid peptide and the S100/calgranulin[13]. Interaction of RAGE ligands with RAGE, initiate a cascade of signalization leading to activation of p21ras, p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappa B (NFKB), which generally results in the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines[14-16]. The implication of AGE/RAGE in diabetes pathophysiology has been demonstrated using RAGE blockade experiments able to inhibit diabetes dysfunctions in vessels or in organs, while AGE injection in mice provoked such dysfunctions[17-19].

T-lymphocytes play an important role in diabetes, either through activation of auto-immune cells directed against beta-pancreatic cells in the case of type 1 diabetes (T1D), or through infiltration of tissues or organs such as adipose tissue (AT) in type 2 diabetes (T2D). In T1D, contribution of AGE/RAGE to diabetes evolution has been clearly demonstrated. For example, RAGE blockade experiments prevented diabetes transfer with diabetogenic T cells in non-obese diabetic/severe combined immuno-deficiency mice[20]. Moreover, T cells from T1D patients or from at risk diabetes relatives, have been shown to express elevated levels of intra-cellular RAGE associated with increased T cell survival and inflammatory cytokine release[21]. AGE/RAGE interaction is also known to play a role in interleukin (IL)-17 immune responses as shown by AGE-mediated up-regulation of RAGE expression in T cells of T1D patients, which resulted in increased IL-17A secretion[22].

The interleukin 17 secreting T helper (Th17) cell subset has been recently discovered as a T-cell inflammatory lineage that mainly secretes IL-17A and IL-17F cytokine whose receptors are ubiquitously expressed[23]. Those receptors are able to spread inflammation due to their ability to activate secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and metalloproteinases following IL-17A binding[24].

We have recently implicated adipose-derived-stem cells (ASC) and adipocytes (AD) in the promotion of Th17 cells through cell-to-cell contact-dependent interactions with blood mononuclear cells (MNC)[25,26]. This function was likely to be mostly displayed by ASC obtained from obese rather than from lean individuals and resulted in inhibiting adipogenesis and insulin response of obese ASC and AD, respectively. In the present study, we aimed to determine the potential role of the AGE/RAGE axis on ASC-mediated Th17 promotion in lean individuals. Therefore, we investigated herein whether glycated albumin would induce IL-17A secretion by T cells, and whether anti-RAGE monoclonal antibody (mAb) would prevent this activation. To this purpose, we co-cultured lean ASC with MNC and treated them with glycated human serum albumin (G-HSA). We observed that G-HSA increased IL-17A secretion but also, Interferon gamma (IFNγ), and Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) secretion and that anti-RAGE mAb specifically inhibited IL-17A secretion.

Subcutaneous or visceral AT samples were isolated from residues of bariatric surgery of obese subjects (body mass index > 30 kg/m²), or visceral surgery of lean controls with the informed consent of patients. AT samples (50-100 mg) were fragmented and incubated in 2 g/L of collagenase type Ia solution (Sigma Aldrich, C2674) dissolved in Dulbecco’s modified eagles medium:Ham F12 (DMEM:F-12) medium (1:1 mL/L) (Invitrogen) for 40 min at 37 °C by mixing. Collagenase action was quenched by the addition of 1:1 mL/L of DMEM:F-12 medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). The released stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was recovered by centrifugation (800 g for 7 min at 25 °C). Residual red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic shock and the ASC component of SVF was selectively expanded in culture medium composed of DMEM:F-12 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Half of the culture medium was changed every two to 3 d. ASC were amplified by several passages in culture (3 to 4) and directly used for experiments or stored in liquid nitrogen. The multipotent phenotype of ASC was validated by differentiating ASC into AD or osteoblasts, depending on the differentiation medium used, as previously reported[25]. ASC phenotype was assessed by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated mouse anti-human cell surface markers (from ImmunoTools GmbH, Friesoythe, Germany) as recommended by the International Society for Cellular Therapy[27], and revealed a cluster of differentiation (CD) 90+, CD105+, CD73+, and CD45- pattern (Supplement Figure 1).

Blood samples were obtained through the Blood Bank Center of Lyon (France), following institutionally approved guidelines. MNC were harvested from healthy human peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Histopaque Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France). MNC were stored in liquid nitrogen prior to use.

ASC were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates (20000 cells/well) for 18-24 h in 200 µL of basal culture medium (DMEM:F-12 medium, 1:1 mL/L supplemented with 10% FCS). 100000 MNC were co-seeded for 48 h in the presence or absence of phytohaemagglutinin (PHA), 5 µg/mL (Sigma-Aldrich). Different ratios of ASC:MNC were used, as indicated in figure legends. Cells were incubated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 supplemented with either 1% human serum albumin (HSA) or 1% G-HSA, both from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France). Supernatant was harvested after 48 h, and frozen. In blockade experiments anti-RAGE monoclonal antibody (RetD Systems, Lille, France) was added at 20 µg/mL during the whole period of culture.

FITC, PE, or APC conjugated mouse anti-human CD73, CD90, CD105, CD3, CD41 CD62P, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), CD8 (all from Immunotools) were used to label the various cells tested. Analyses were performed using the “LSR II 3 lasers” cytofluorometer and the Diva software (both were from BD Biosciences).

IL-17A, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα secretions were measured by ELISA, using the corresponding antibodies (e-Biosciences, Paris, France).

One- or two-way repeated measures ANOVA, were used to compare multiple criteria. When some values were missing, mixed effects analyses were used. When the ANOVA or mixed effects analyses were significant, Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to do two-by-two analyses, taking into account the multiple comparisons. Paired t tests were used to compare two criteria, in univariate analysis. Differences were considered as statistically significant when P value was < 0.05. The analyses were done using Graphpad Prism 8 software.

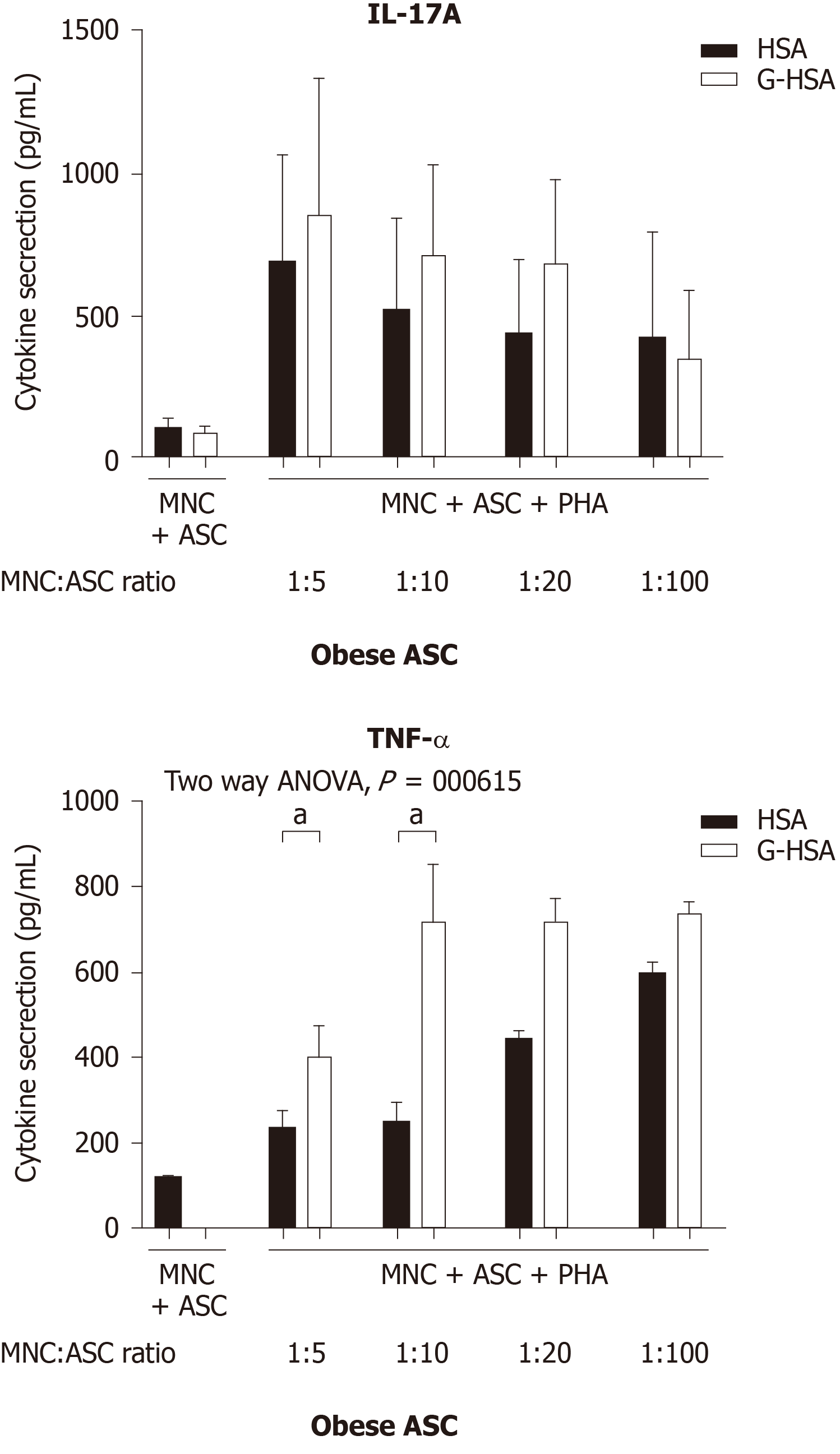

We have previously reported that obese ASC activate IL-17A production by T cells in the presence of PHA. To investigate whether glycated albumin would increase the levels of IL-17A, we co-cultured the cells either in the presence of 1% HSA, or 1% G-HSA. Graded concentrations of ASC were co-cultured with the optimal concentration of MNC and activated with PHA. Although IL-17A secretion weakly increased, the two-way ANOVA multi-comparison tests did not show significant results whether HSA or G-HSA were added to cultures. But TNFα clearly increased (P = 0.0165 in two-way ANOVA). Thus, these results demonstrated a weak, but non-significant effect of G-HSA on Th17 stimulation by obese ASC, but an increase in TNFα production.

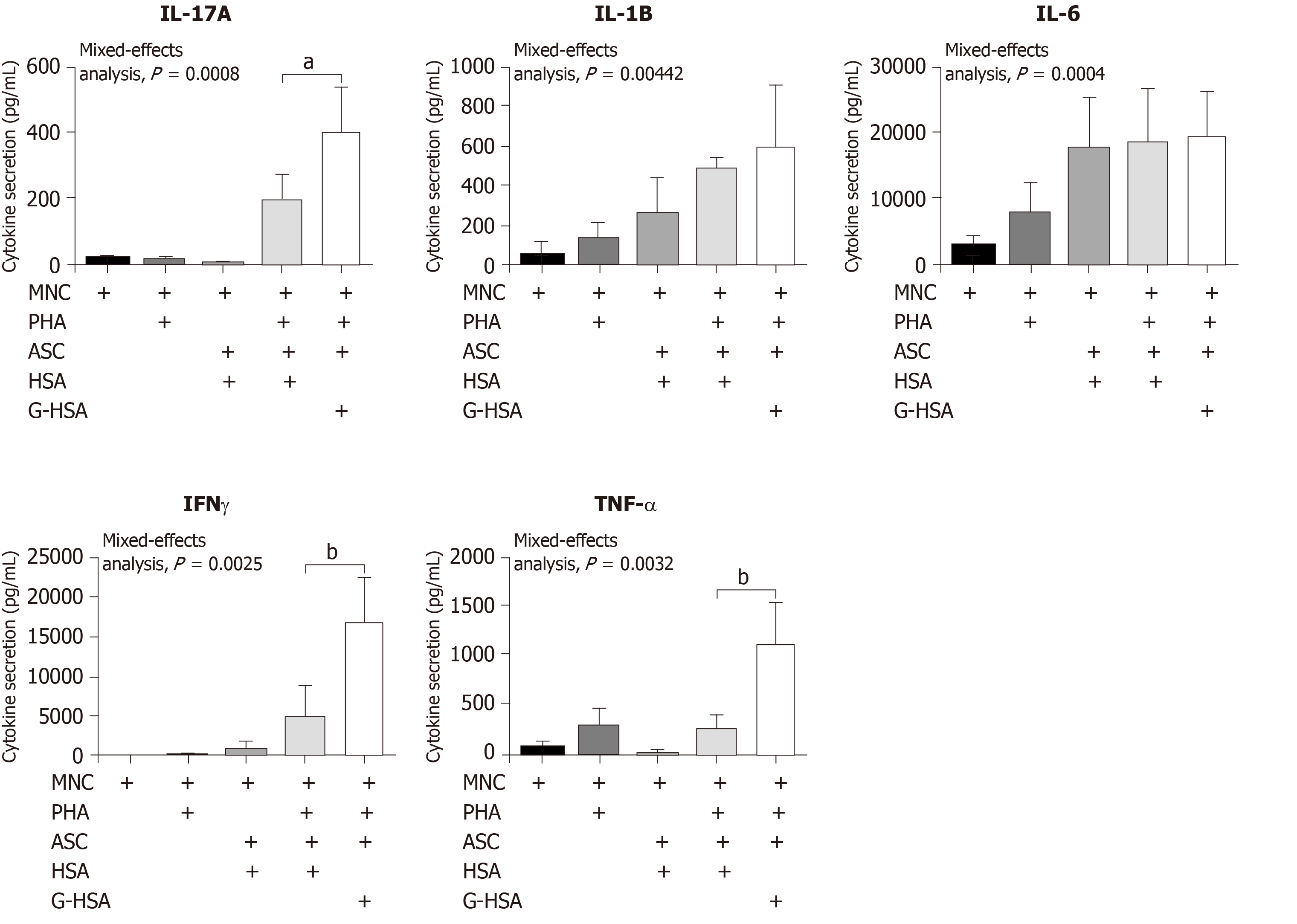

Because we have previously reported that lean ASC mediate IL-17A production at much lower levels than obese ASC, we investigated whether AGE could increase this production. Therefore, we co-cultured lean ASC with MNC in the presence of HSA, or G-HSA, and activated the co-cultures with PHA. Secretion of IL-17A was measured and showed a significant increase in the presence of G-HSA (P = 0.0196 in post-hoc Bonferroni tests). Interestingly, T helper 1 cytokines were also increased in the presence of G-HSA such as IFNγ (P = 0.0065 in Bonferroni post-hoc tests), and TNFα (P = 0.0037 in Bonferroni post-hoc tests). However, IL-6 and IL-1β, which are mostly secreted by ASC and monocytes in this model, did not show significant differences in post-hoc Bonferroni tests, even though mixed effect analyses showed significancy, suggesting a specific effect of G-HSA on T cells.

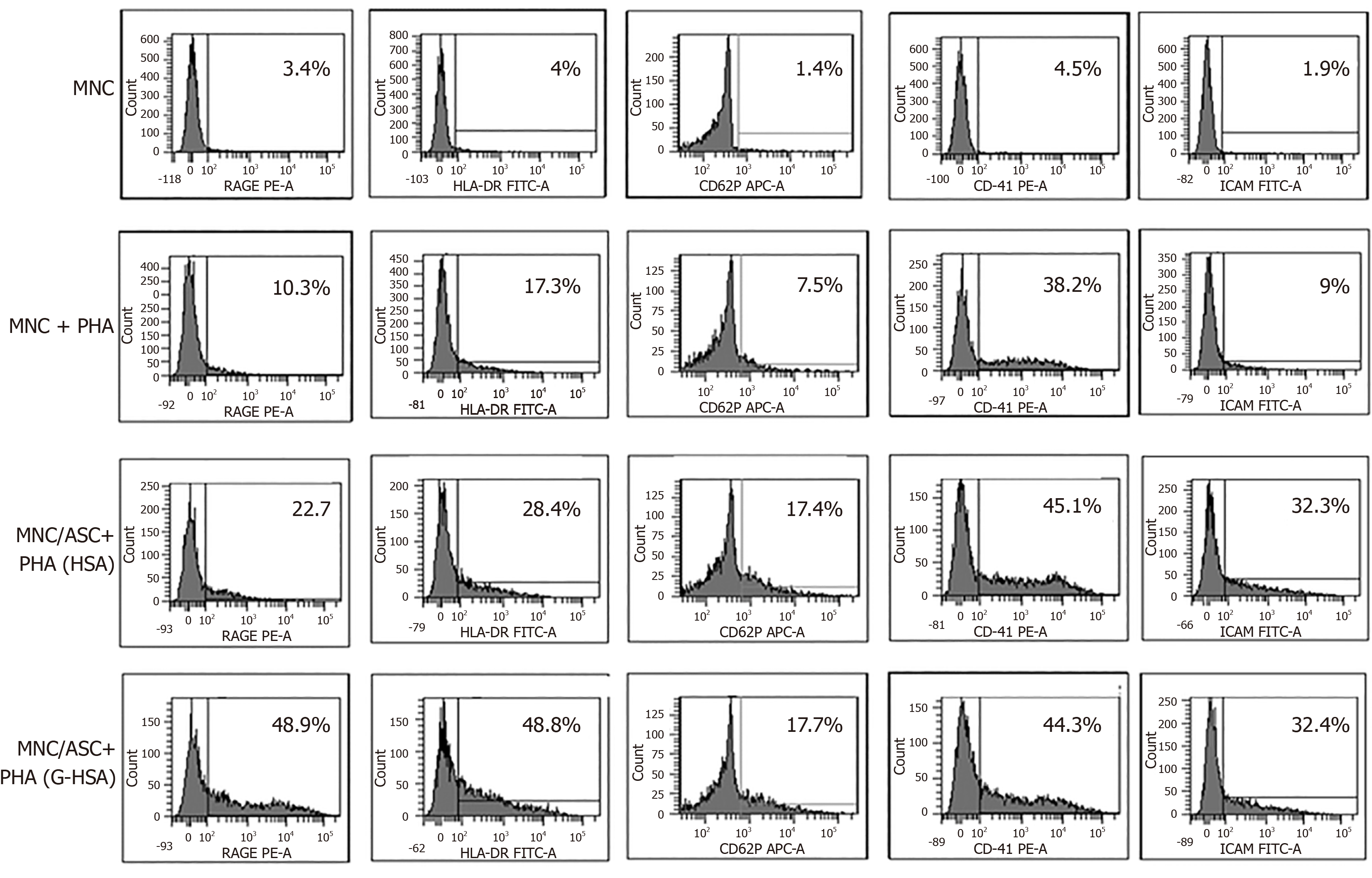

We then investigated whether RAGE expression would be increased in the co-cultures of lean ASC and T cells leading to IL-17A production. We observed that the expression of RAGE was clearly increased when G-HSA was present. Moreover, HLA-DR expression was upregulated together with RAGE expression, in the presence of G-HSA.

Previous reports have demonstrated that glycated albumin induces platelet aggregation and activation[28,29]. Therefore, we measured the expression of CD62P and CD41 surface molecules, which are markers of platelet activation and aggregation, respectively, in experiments where T cells were either cultured alone, or co-cultured with ASC, in the presence of PHA and G-HSA, or HSA. Whereas markers of platelet aggregation and activation increased in activated ASC/MNC co-cultures, no difference was observed whether G-HSA or HSA was present. ICAM-1 expression, which has also been shown to increase in endothelial cells under the influence of RAGE activation[30] and in co-cultures of obese ASC with T cells[31], did not increase in the presence of G-HSA.

Therefore, these results suggested a specific effect of G-HSA on RAGE and HLA-DR expression in co-cultured cells.

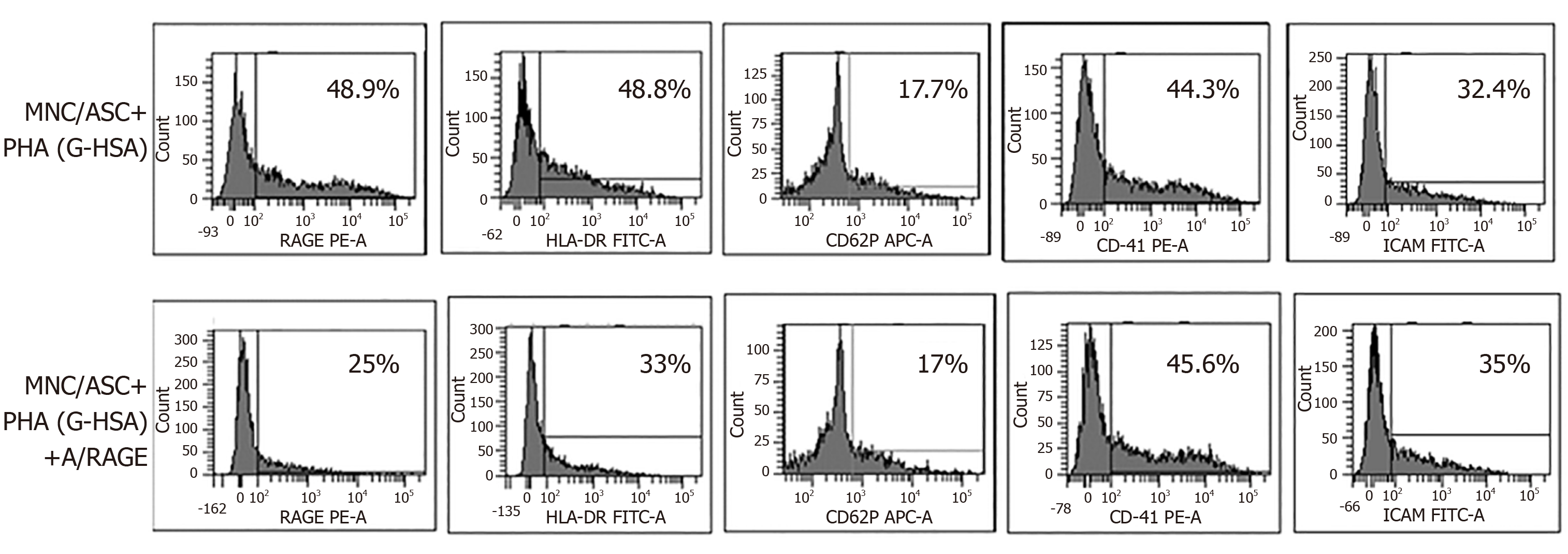

To better define the effects of G-HSA on RAGE and HLA-DR expression, we then added anti-RAGE mAb during co-cultures of lean ASC with MNC for 48 h, and measured the expression of RAGE, HLA-DR, CD41, CD62P and ICAM-1. As expected, RAGE expression decreased. Among the other molecules that were analyzed, only HLA-DR expression decreased down to the levels of cells co-cultured in the presence of HSA.

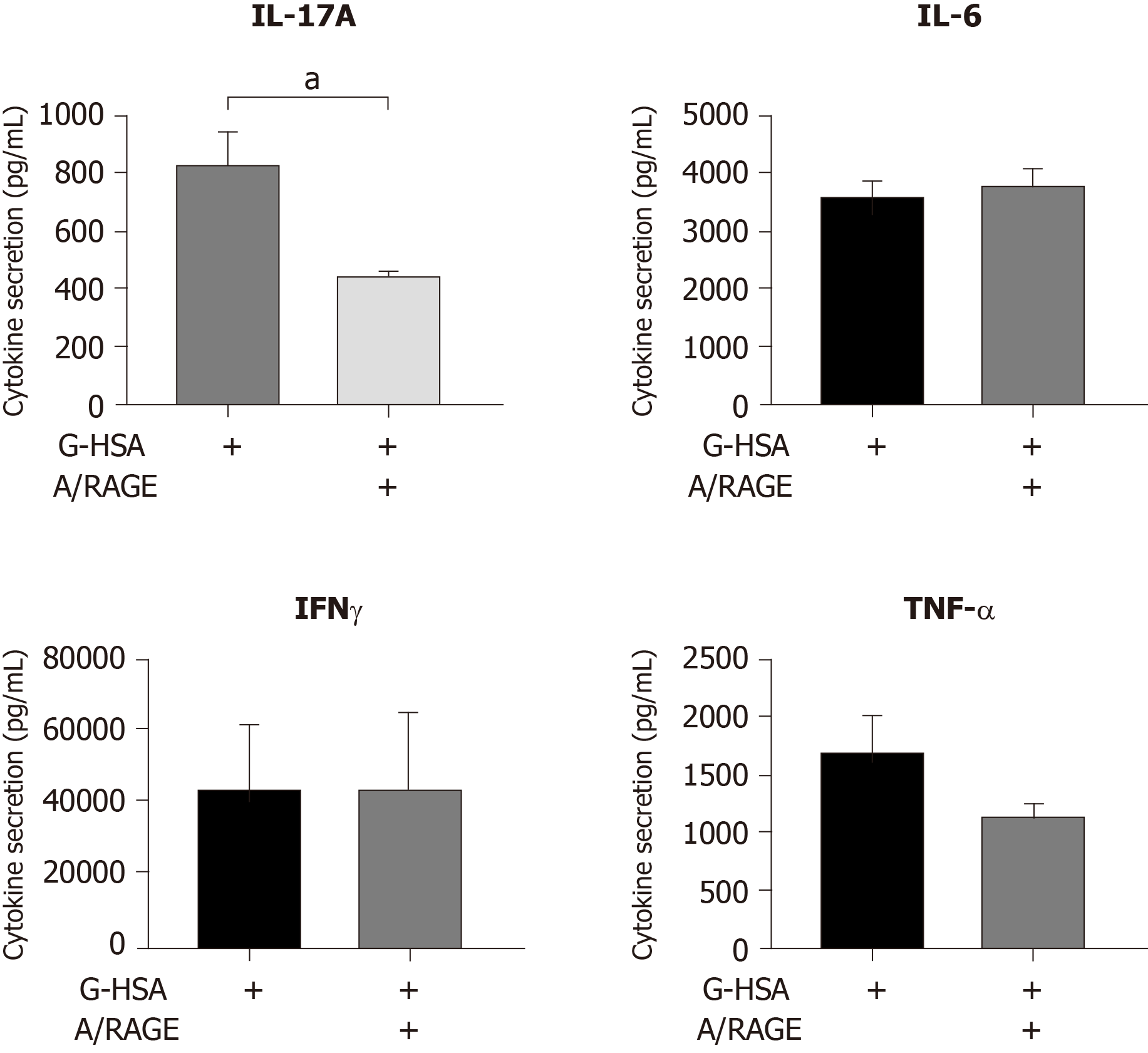

Because the anti-RAGE antibody was able to inhibit RAGE and HLA-DR expression, we then investigated whether anti-RAGE mAb could inhibit IL-17A production. Therefore, co-cultures of PHA-activated ASC/MNC cells were performed in the presence or absence of anti-RAGE mAb. Results showed that IL-17A secretion significantly decreased in the presence of anti-RAGE mAb (P = 0.0402 in paired t tests), but not IFNγ, nor TNFα, although a trend was observed for the latter. Therefore, our results suggested that RAGE might be specifically implicated in lean ASC-mediated IL-17A production, but not in IFNγ or TNFα secretion.

IL-17A/F are pro-inflammatory cytokines known to play an important role in AT-low grade inflammation in obese individuals, possibly leading to T2D[25,32-36]. Interestingly, IL-17A/F cytokines have also been involved in the pathogenicity of T1D[37], notably through their peri-pancreatic fat location[38,39]. Indeed, deletion of sentrin-specific protease 1 (SENP1), a SUMO-specific protease in AT, resulted in activating NFKB and pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine secretion in peri-pancreatic AT, ultimately leading to the recruitment of immune cells, including Th17 cells[38]. Subsequent to induced beta cell death and pancreatic disruption, spontaneous development of T1D was further observed in these SENP1-invalidated mice[39]. Strengthening the potential role of pancreatic fat as a pathogenic factor leading to beta cell dysfunction is the demonstration that pancreatic fat has been negatively associated with insulin secretion in individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance[40]. Moreover in this study, pancreatic fat was found to be a stronger determinant of impaired insulin secretion than visceral fat[40]. In the present study, we investigated whether AGE could be involved in the dysfunction of lean AT, through increase of IL-17A production by T cells interacting with adipocyte progenitors. To address this question, we used the co-culture model that we have previously reported to lead to Th17 cell activation by ASC[25], and added low concentrations of HSA or G-HSA. When using obese ASC, we observed only a weak, but not significant effect of G-HSA on increased IL-17A production, suggesting other mechanisms than AGE in obese-ASC-mediated IL-17A secretion (Figure 1). However, when lean ASC/MNC co-cultures were incubated in the presence of 1% G-HSA, a significant increase of IL-17A production was observed, together with increased IFNγ and TNFα production. This increase was probably related to specific activation of T cells by G-HSA, as neither IL-1β nor IL-6 significantly increase (Figure 2).

RAGE is one of the AGE receptors and has been widely implicated in most of the pro-inflammatory mechanisms mediated by AGE and leading to chronic inflammation disorders. They are constitutively expressed in T cells from diabetic patients, and are known to activate the NFKB pathway leading to inflammatory cytokine production[15]. However, not all T cells are regulated by RAGE, as shown by Chen et al[20] who demonstrated a differential effect of RAGE blockade on splenic T cells but not on fully activated T cells in a transfer model of diabetes. Supporting these results, we also demonstrated herein that RAGE was involved in Th17 cell, but not Th1 cell activation, since only IL-17A secretion was inhibited by anti-RAGE mAb (Figure 5). A similar differential effect of RAGE on IL-17A and TNFα production was also observed in T1D, where RAGE positive T cells were found to express higher levels of IL-17A but not TNFα nor IFNγ, as compared with RAGE negative cells in the same patients. This demonstrated thus a potentiating effect of RAGE signaling pathway on IL-17A production[22]. Confirming the implication of RAGE in ASC-mediated T cell activation, we observed increased RAGE expression, together with HLA-DR expression when G-HSA was added to the co-cultures, and an abolition of this effect in the presence of RAGE mAb which concomitantly resulted in inhibition of IL-17A production (Figures 4 and 5). Finally, although glycated albumin has been shown to increase platelet aggregation[28,29],we did not find its involvement in AGE-mediated activation of T cell secretion. Indeed, up-regulation of CD41 and CD62P expression, two markers of platelet aggregation and activation respectively, did not further increase in the presence of G-HSA (Figure 3). Moreover, RAGE mAb did not inhibit the expression of these two markers, either (Figure 4). ICAM-1 expression, which has been shown to be up-regulated by AGE in other cell models[41], did not increase in the presence of AGE, and was not inhibited by RAGE mAb (Figures 3 and 4). Therefore, we concluded that in our model platelet aggregation and ICAM-1 were not involved in the potentiation of Th17 cytokines production by G-HSA.

In conclusion, we have shown herein that the presence of G-HSA enhances lean ASC-mediated IL-17A production through a mechanism requiring RAGE signaling. Moreover, our study suggests a new mechanism by which ASC could contribute to inflammatory processes through AGE-mediated IL-17A production in AT of lean individuals. This could be potentially of importance in the context of T1D pathophysiology.

Advanced glycation end products (AGE) are involved in type 1 diabetes (T1D) through reduction of glucose uptake and attenuation of insulin sensitivity. Moreover, AGE are known to promote interleukin (IL)-17A secreting T cells.

Adipose Tissue (AT), and especially pancreatic AT is a pathogenic factor leading to beta cell destruction partly due to IL-17A secreting T helper (Th17) cell recruitment; IL-17A/F are pro-inflammatory cytokines known to play an important role in AT-low grade inflammation and propagation of inflammation outside AT.

We have previously shown that adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) promote Th17 cells in obese AT, but not or less in lean AT. Here, we investigated whether AGE could improve lean ASC ability to promote IL-17A production by T cells.

With this aim, we cocultured ASC from lean AT with mononuclear cells in the presence of glycated human serum albumin (G-HSA) or human serum albumin. We then analyzed the influence of AGE by blocking their ability to bind to receptor of advanced glycated end products (RAGE). IL-17A and other pro-inflammatory cytokine secretions were measured, together with surface expression of RAGE, and other relevant molecules.

We have demonstrated herein that G-HSA enhances IL-17A, interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion by MNC in the presence of ASC harvested from lean individuals. This effect involves the RAGE/AGE axis as assessed by anti-RAGE blocking monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and is associated with increased expression of RAGE and human leukocyte antigen-DR molecules.

Thus, our results demonstrate that G-HSA is able to improve lean ASC-mediated IL-17A production in AT, suggesting a new mechanism by which AGE could contribute to T1D pathophysiology.

Here we propose a mechanism by which AT can lead to the recruitment of Th17 cells in lean individuals through activation of the AGE/RAGE axis. Because pancreatic fat has been involved in the pathogenicity of T1D, this model deserves to be validated in animal studies, in order to evaluate the efficacy of RAGE blocking mAb as a therapeutic tool.

We wish to thank Yassine Corbin, for his help in English editing corrections.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Popovic DS, Ventura C S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Rondeau P, Navarra G, Cacciabaudo F, Leone M, Bourdon E, Militello V. Thermal aggregation of glycated bovine serum albumin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vlassara H. Advanced glycation in health and disease: role of the modern environment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:452-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ulrich P, Cerami A. Protein glycation, diabetes, and aging. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Castellani R, Smith MA, Richey PL, Perry G. Glycoxidation and oxidative stress in Parkinson disease and diffuse Lewy body disease. Brain Res. 1996;737:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jeffcoate SL. Diabetes control and complications: the role of glycated haemoglobin, 25 years on. Diabet Med. 2004;21:657-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arasteh A, Farahi S, Habibi-Rezaei M, Moosavi-Movahedi AA. Glycated albumin: an overview of the In Vitro models of an In Vivo potential disease marker. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hashimoto K, Osugi T, Noguchi S, Morimoto Y, Wasada K, Imai S, Waguri M, Toyoda R, Fujita T, Kasayama S, Koga M. A1C but not serum glycated albumin is elevated because of iron deficiency in late pregnancy in diabetic women. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:509-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yoshiuchi K, Matsuhisa M, Katakami N, Nakatani Y, Sakamoto K, Matsuoka T, Umayahara Y, Kosugi K, Kaneto H, Yamasaki Y, Hori M. Glycated albumin is a better indicator for glucose excursion than glycated hemoglobin in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2008;55:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nagayama H, Inaba M, Okabe R, Emoto M, Ishimura E, Okazaki S, Nishizawa Y. Glycated albumin as an improved indicator of glycemic control in hemodialysis patients with type 2 diabetes based on fasting plasma glucose and oral glucose tolerance test. Biomed Pharmacother. 2009;63:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wautier JL, Wautier MP, Schmidt AM, Anderson GM, Hori O, Zoukourian C, Capron L, Chappey O, Yan SD, Brett J. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) on the surface of diabetic erythrocytes bind to the vessel wall via a specific receptor inducing oxidant stress in the vasculature: a link between surface-associated AGEs and diabetic complications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7742-7746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:949-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neeper M, Schmidt AM, Brett J, Yan SD, Wang F, Pan YC, Elliston K, Stern D, Shaw A. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14998-15004. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wautier MP, Guillausseau PJ, Wautier JL. Activation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and consequences on health. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11:305-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ishihara K, Tsutsumi K, Kawane S, Nakajima M, Kasaoka T. The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) directly binds to ERK by a D-domain-like docking site. FEBS Lett. 2003;550:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cohen MP, Shea E, Chen S, Shearman CW. Glycated albumin increases oxidative stress, activates NF-kappa B and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and stimulates ERK-dependent transforming growth factor-beta 1 production in macrophage RAW cells. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;141:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yeh CL, Hu YM, Liu JJ, Chen WJ, Yeh SL. Effects of supplemental dietary arginine on the exogenous advanced glycosylation end product-induced interleukin-23/interleukin-17 immune response in rats. Nutrition. 2012;28:1063-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wautier JL, Zoukourian C, Chappey O, Wautier MP, Guillausseau PJ, Cao R, Hori O, Stern D, Schmidt AM. Receptor-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction in diabetic vasculopathy. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products blocks hyperpermeability in diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:238-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu X, Li Z, Luo D, Huang Y, Zhu J, Wang X, Hu H, Patrick CP. Exogenous advanced glycosylation end products induce diabetes-like vascular dysfunction in normal rats: a factor in diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhou G, Li C, Cai L. Advanced glycation end-products induce connective tissue growth factor-mediated renal fibrosis predominantly through transforming growth factor beta-independent pathway. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2033-2043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen Y, Yan SS, Colgan J, Zhang HP, Luban J, Schmidt AM, Stern D, Herold KC. Blockade of late stages of autoimmune diabetes by inhibition of the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Immunol. 2004;173:1399-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Durning SP, Preston-Hurlburt P, Clark PR, Xu D, Herold KC; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group. The Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts Drives T Cell Survival and Inflammation in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J Immunol. 2016;197:3076-3085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Akirav EM, Preston-Hurlburt P, Garyu J, Henegariu O, Clynes R, Schmidt AM, Herold KC. RAGE expression in human T cells: a link between environmental factors and adaptive immune responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gaffen SL. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:556-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1174] [Cited by in RCA: 1138] [Article Influence: 71.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Song X, Qian Y. The activation and regulation of IL-17 receptor mediated signaling. Cytokine. 2013;62:175-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eljaafari A, Robert M, Chehimi M, Chanon S, Durand C, Vial G, Bendridi N, Madec AM, Disse E, Laville M, Rieusset J, Lefai E, Vidal H, Pirola L. Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells From Obese Subjects Contribute to Inflammation and Reduced Insulin Response in Adipocytes Through Differential Regulation of the Th1/Th17 Balance and Monocyte Activation. Diabetes. 2015;64:2477-2488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chehimi M, Robert M, Bechwaty ME, Vial G, Rieusset J, Vidal H, Pirola L, Eljaafari A. Adipocytes, like their progenitors, contribute to inflammation of adipose tissues through promotion of Th-17 cells and activation of monocytes, in obese subjects. Adipocyte. 2016;5:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bourin P, Bunnell BA, Casteilla L, Dominici M, Katz AJ, March KL, Redl H, Rubin JP, Yoshimura K, Gimble JM. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT). Cytotherapy. 2013;15:641-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1199] [Cited by in RCA: 1367] [Article Influence: 113.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Rubenstein DA, Yin W. Glycated albumin modulates platelet susceptibility to flow induced activation and aggregation. Platelets. 2009;20:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Soaita I, Yin W, Rubenstein DA. Glycated albumin modifies platelet adhesion and aggregation responses. Platelets. 2017;28:682-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Basta G, Schmidt AM, De Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products and vascular inflammation: implications for accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:582-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chehimi M, Ward R, Pestel J, Robert M, Pesenti S, Bendridi N, Michalski MC, Laville M, Vidal H, Eljaafari A. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Inhibit IL-17A Secretion through Decreased ICAM-1 Expression in T Cells Co-Cultured with Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Harvested from Adipose Tissues of Obese Subjects. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1801148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fabbrini E, Cella M, McCartney SA, Fuchs A, Abumrad NA, Pietka TA, Chen Z, Finck BN, Han DH, Magkos F, Conte C, Bradley D, Fraterrigo G, Eagon JC, Patterson BW, Colonna M, Klein S. Association between specific adipose tissue CD4+ T-cell populations and insulin resistance in obese individuals. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:366-374. e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | McLaughlin T, Liu LF, Lamendola C, Shen L, Morton J, Rivas H, Winer D, Tolentino L, Choi O, Zhang H, Hui Yen Chng M, Engleman E. T-cell profile in adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance and systemic inflammation in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2637-2643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dalmas E, Venteclef N, Caer C, Poitou C, Cremer I, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Bayry J, Kaveri SV, Clément K, André S, Guerre-Millo M. T cell-derived IL-22 amplifies IL-1β-driven inflammation in human adipose tissue: relevance to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63:1966-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bertola A, Ciucci T, Rousseau D, Bourlier V, Duffaut C, Bonnafous S, Blin-Wakkach C, Anty R, Iannelli A, Gugenheim J, Tran A, Bouloumié A, Gual P, Wakkach A. Identification of adipose tissue dendritic cells correlated with obesity-associated insulin-resistance and inducing Th17 responses in mice and patients. Diabetes. 2012;61:2238-2247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chehimi M, Vidal H, Eljaafari A. Pathogenic Role of IL-17-Producing Immune Cells in Obesity, and Related Inflammatory Diseases. J Clin Med. 2017;6:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Abdel-Moneim A, Bakery HH, Allam G. The potential pathogenic role of IL-17/Th17 cells in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;101:287-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Shao L, Feng B, Zhang Y, Zhou H, Ji W, Min W. The role of adipose-derived inflammatory cytokines in type 1 diabetes. Adipocyte. 2016;5:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shao L, Zhou HJ, Zhang H, Qin L, Hwa J, Yun Z, Ji W, Min W. SENP1-mediated NEMO deSUMOylation in adipocytes limits inflammatory responses and type-1 diabetes progression. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Heni M, Machann J, Staiger H, Schwenzer NF, Peter A, Schick F, Claussen CD, Stefan N, Häring HU, Fritsche A. Pancreatic fat is negatively associated with insulin secretion in individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance: a nuclear magnetic resonance study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:200-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Basta G, Lazzerini G, Massaro M, Simoncini T, Tanganelli P, Fu C, Kislinger T, Stern DM, Schmidt AM, De Caterina R. Advanced glycation end products activate endothelium through signal-transduction receptor RAGE: a mechanism for amplification of inflammatory responses. Circulation. 2002;105:816-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |