Published online Jan 26, 2020. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i1.70

Peer-review started: April 14, 2019

First decision: May 16, 2019

Revised: August 16, 2019

Accepted: September 26, 2019

Article in press: September 26, 2019

Published online: January 26, 2020

Processing time: 261 Days and 19.9 Hours

Recently, the exclusive use of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-secreted molecules, named as the secretome, have been evaluated for overcoming the limitations of cell-based therapy while maintaining its advantages.

To improve cell-free therapy by adding disease-specificity through stimulation of MSCs using disease-causing materials.

We collected the secretory materials (named as inducers) released from AML12 hepatocytes that had been pretreated with thioacetamide (TAA) and generated the TAA-induced secretome (TAA-isecretome) after stimulating adipose-derived stem cells with the inducers. The TAA-isecretome was intravenously administered to mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure and those with partial hepatectomy.

TAA-isecretome infusion showed higher therapeutic potential in terms of (1) restoring disorganized hepatic tissue to normal tissue; (2) inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α); and (3) reducing abnormally elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) compared to the naïve secretome infusion in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. However, the TAA-isecretome showed inferior therapeutic potential for restoring hepatic function in partially hepatectomized mice. Proteomic analysis of TAA-isecretome identified that antioxidant processes were the most predominant enriched biological networks of the proteins exclusively identified in the TAA-isecretome. In addition, peroxiredoxin-1, a potent antioxidant protein, was found to be one of representative components of TAA-isecretome and played a central role in the protection of TAA-induced hepatic injury.

Appropriate stimulation of adipose-derived stem cells with TAA led to the production of a secretome enriched with proteins, especially peroxiredoxin-1, with higher antioxidant activity. Our results suggest that appropriate stimulation of MSCs with pathogenic agents can lead to the production of a secretome specialized for protecting against the pathogen. This approach is expected to open a new way of developing various specific therapeutics based on the high plasticity and responsiveness of MSCs.

Core tip: Appropriate stimulation of adipose-derived stem cells with thioacetamide (TAA) led to the production of a secretome enriched with proteins, especially peroxiredoxin-1, with higher antioxidant activity. Free radicals are principal pathogenic agents in the pathogenesis of TAA-induced hepatic injury. The TAA-induced secretome was superior to the naïve secretome in restoring hepatic function while minimizing inflammatory processes in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. However, it was less effective in the mice with partial hepatectomy, suggestive of disease-specificity. Our results suggest that appropriate stimulation of adipose-derived stem cells with pathogenic agents can lead to the production of a secretome specialized for protecting against the pathogen.

- Citation: Kim OH, Hong HE, Seo H, Kwak BJ, Choi HJ, Kim KH, Ahn J, Lee SC, Kim SJ. Generation of induced secretome from adipose-derived stem cells specialized for disease-specific treatment: An experimental mouse model. World J Stem Cells 2020; 12(1): 70-86

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v12/i1/70.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v12.i1.70

For several decades, numerous efforts have been made to harness the potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for biotherapeutic applications. MSCs have a variety of advantages, including high availability, ease of isolation and expansion, functional plasticity, and low immunogenicity[1-3]. Although application of MSCs has shown promising preclinical and clinical outcomes, their clinical applications remain challenging, possibly because of their genetic instability during in vitro expansion, poor growth kinetics, early senescence, and particularly the potential for malignant transformation[4-9].

Recently, the exclusive use of MSC-secreted molecules rather than the cells alone has gained attention for overcoming the limitations of cell-based therapy while maintaining its advantages. The total set of molecules secreted or surface-shed by cells is generally referred to as the secretome. The secretome includes bioactive peptides, such as cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors[10,11]. Accumulating evidence supports that the principal action mechanism of MSCs is secretome-mediated[10,12-14]. These soluble factors are released from MSCs either alone or in extracellular vesicles (EVs). Therefore, using these cell-free products may indeed represent an alternative to therapies based on cell transplantation.

The composition of the secretome is influenced by various external factors, including the cell source, type of culture media, culturing period, and preconditioning treatment. Therefore, one can use a secretome therapeutically either without manipulation or by manipulating MSCs to release specific secretome components. The latter includes (1) adjustments to the physicochemical environment during secretome preparations; and (2) development of genetically-engineered MSCs. We previously validated the amplified therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cell (ASC)-secretome by physicochemically controlling the secretome-obtaining process, such as hypoxic preconditioning[15,16] or using an endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide)[17].

Interestingly, proteomic analysis of EVs obtained from hepatocytes exposed to liver toxins revealed that they contained higher levels of vital liver-specific proteins, such as carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1, S-adenosyl methionine synthetase 1, and catechol-O-methyltransferase[18,19]. This suggests that MSCs can be induced to generate a specialized secretome customized to a specific disease. We herein defined induced secretome (isecretome) as the secretome released from MSCs that had been stimulated by disease-causing materials to treat the specific disease. Thioacetamide (TAA) is a well-known hepatotoxin. In this study, we attempted to validate the higher therapeutic effects of the secretome induced by TAA (TAA-isecretome) compared to the naïve secretome, specifically in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. If the superiority of an isecretome over a naïve secretome is demonstrated, it could provide a foundation for producing a disease-specific isecretome applicable to specific diseases.

The AML12 mouse hepatocyte cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, United States). AML12 cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Ham's F-12; Thermo, Carlsbad, CA, United States). The medium was supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum; GibcoBRL, Carlsbad, CA, United States), 1% antibiotics (Thermo), 1x ITS supplement (Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium-G supplement; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), and 40 ng/ml dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) at 37 °C. Human ASCs were kindly donated by Hurim BioCell Co. (Seoul, South Korea). ASCs were cultured in MesenPRO RS basal medium (GibcoBRL) supplemented with antibiotics (Penicillin-streptomycin; GibcoBRL) at 37 °C.

After reaching 70%–80% confluence, ASCs were refed with serum free DMEM low-glucose medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The conditioned media (CM) obtained from each set of ASCs were concentrated by 25-fold using ultrafiltration units (Amicon Ultra-PL 3; Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States) with a 3-kDa cutoff. The concentrated CM, which had been attained from TAA-untreated, TAA-treated, and pcDNA-HBx[20] transfected culturing conditions, was named as CM (or control secretome), TAA-induced CM (TAA-iCM, representing the TAA-isecretome), and HBx-induced CM (HBx-iCM), respectively.

Cell proliferation was evaluated with 2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (water soluble tetrazolium salt, WST-1) assay using EZ-Cytox Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Itsbio, Seoul, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the microplate reader (model 680; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States)[16].

AML12 cells and liver specimens obtained from mice were lysed using the EzRIPA Lysis kit (ATTO Corporation; Tokyo, Japan) and quantified by Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Proteins were visualized by western analysis using the following primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) at 4 °C overnight and then with horseradish (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000 dilution) for 1 h at 25 °C[16]. From Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, United States), we obtained primary antibodies against BAX (Bcl-2-like protein 4), BIM (Bcl-2-like protein 11), GPx (glutathione peroxidase), HGF (hepatocyte growth factor), Mcl-1 (myeloid cell leukemia 1), PARP (poly ADP-ribose polymerase), PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), p-ERK (phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase), p-STAT3, SOD (superoxide dismutase), STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), c-caspase-3 (cleaved caspase 3), fibronectin, F4/80, p-ERK, β-actin, and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Specific immune complexes were detected using the Western Blotting Plus Chemiluminescence Reagent (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States).

Eight-week-old male BALB/c mice (Damool Science, Daejeon, South Korea) were used in this study. Animal studies were carried out in compliance with the guidelines of the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, Korea (IRB No: CMCDJ-AP-2016-001). We compared the effects of the TAA-isecretome in an in vivo model of TAA-induced hepatic failure. The in vivo model was generated by subcutaneous injection of TAA (300 mg/kg, 24 h intervals for 2 d) into experimental mice. Subsequently, control mice and TAA-treated mice were intravenously (using tail vein) infused with normal saline (n = 15), CM (n = 15), and TAA-iCM (n = 15). An in vivo model of 70% partial hepatectomy was performed (n = 12)[21].

Blood samples were collected from each mouse, centrifuged for 10 min at 9500 g, and serum was collected. We measured the concentrations of markers for liver injury and kidney injury, such as aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and creatine, using an IDEXX VetTest Chemistry Analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, ME, United States). The concentrations of mouse IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α were measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mouse livers and kidneys from each group were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 µm thickness. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The scores for the severity of liver and kidney injury were as follows: 1 (normal); 2 (mild injury); 3 (moderate injury); and 4 (severe injury). Three liver sections were examined per mouse, and three randomly selected high-power fields (40x) were analyzed for each liver section. The mean score for each animal was determined by summing all scores.

For immunohistochemical analysis, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated in an ethanol series, and subjected to epitope retrieval using standard procedures. Antibodies against CD68, PECAM (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule), and albumin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States) were used for immunochemical staining. The samples were then examined under a laser-scanning microscope (Eclipse TE300; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to analyze the expression of CD68, PECAM, and albumin.

All digested peptides were separated and identified using online nano liquid chromatography and analyzed by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. For peptide identification, MS/MS spectra were searched by MASCOT (Matrix science, version 2.41)[22]. The genome sequence of the Uniprot_Human was used as the database for protein identification. To predict affected pathways among the differentially expressed genes, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis were performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and SigmaPlot® ver. 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical comparison among groups was determined using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s test as the post hoc analysis. Probability values of P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

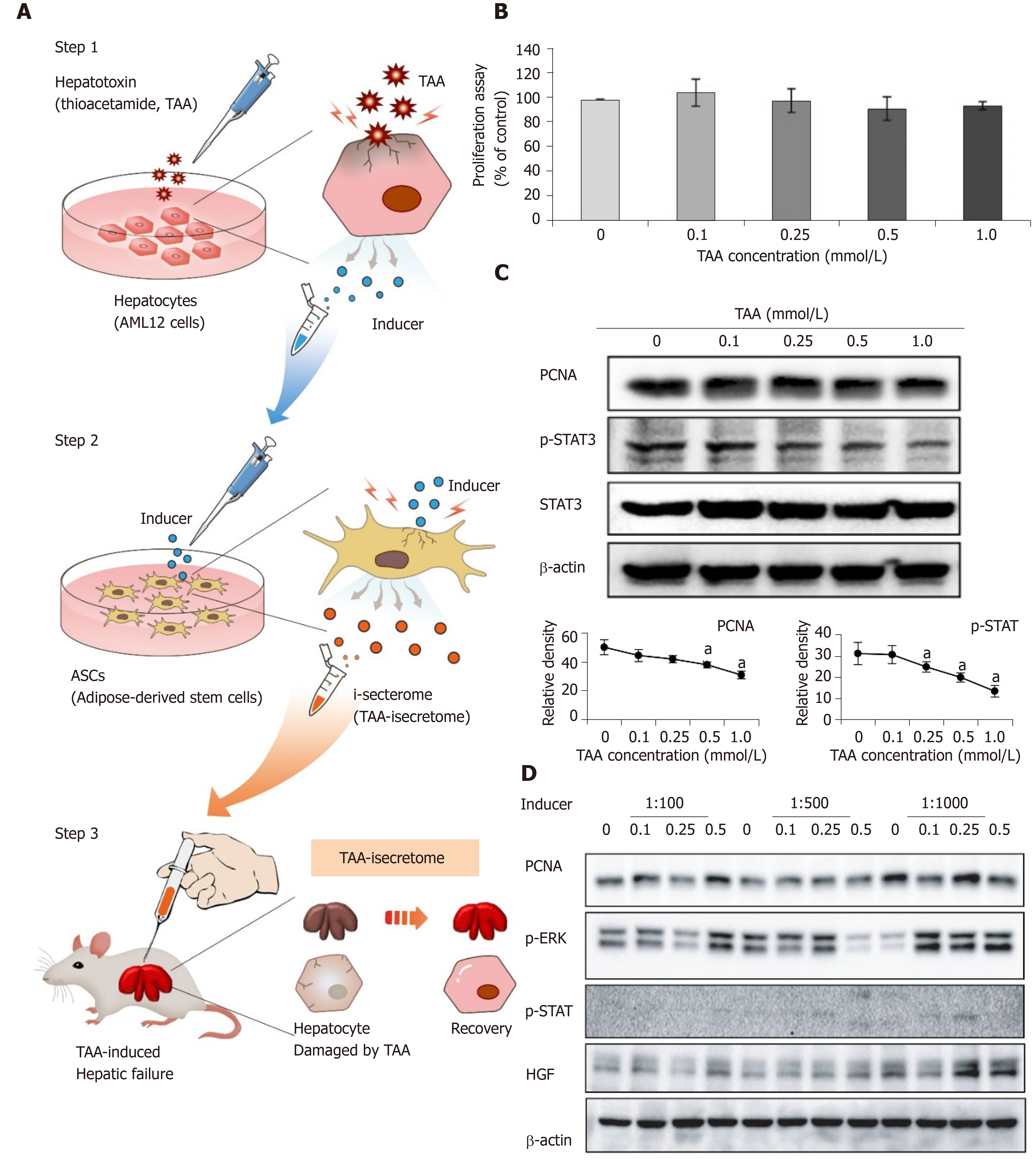

Figure 1A shows the concept of generating the TAA-isecretome for treating TAA-induced hepatic failure. We first determined the TAA concentration required to produce the TAA-isecretome. To achieve this, we investigated AML12 cell proliferation and the expression of proliferation intermediates (PCNA, p-STAT3, and STAT3) in AML12 cells at different TAA concentrations (Figure 1B and 1C). We found that 0.25 mmol/L TAA was appropriate because it moderately increased proliferation intermediates without significantly decreasing cell viability. We named the secretory materials released from TAA-treated AML12 cells as “inducer.”

Next, we examined the dilution rate of inducers that maximizes the expression of the proliferation markers (PCNA, p-ERK, p-STAT, and HGF) in ASCs. Of the tested dilution rates (1:100, 1:500, and 1:1000), 1:1000 maximally induced the expression of these markers (Figure 1D).

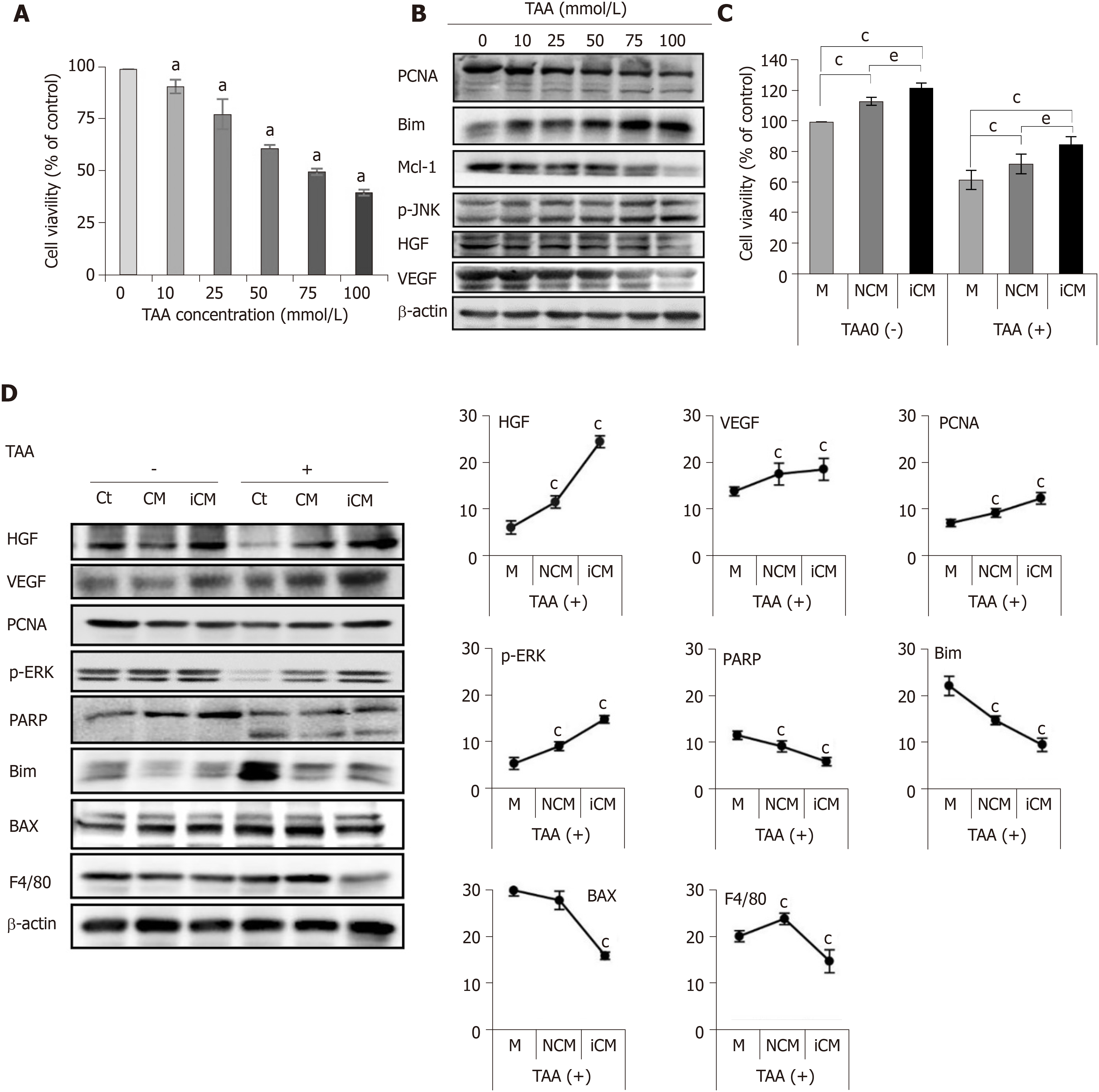

Next, we evaluated the effects of the TAA-isecretome in an in vitro model of TAA-induced hepatic failure. We found that 50 mM TAA was effective for generating the in vitro model of TAA-induced hepatic failure based on the results of cell viability assay and western blot analyses (Figure 2A and 2B). Briefly, we named the secretome obtained from 48 h of incubation of ASCs as CM (normal conditioned media) and that used to generate the TAA-isecretome as iCM (induced conditioned media). We then treated normal and TAA-treated hepatocytes with CM and iCM, respectively. Cell viability tests showed that iCM-treated hepatocytes had the highest cell viability in both normal and TAA-treated hepatocytes (Figure 2C). Additionally, iCM-treated hepatocytes showed the highest expression of markers reflecting liver regeneration (HGF, VEGF, PCNA, and p-ERK) and lowest expression of markers reflecting apoptosis and inflammation (PARP, BIM, BAX, and F4/80) by western blot analysis (Figure 2D).

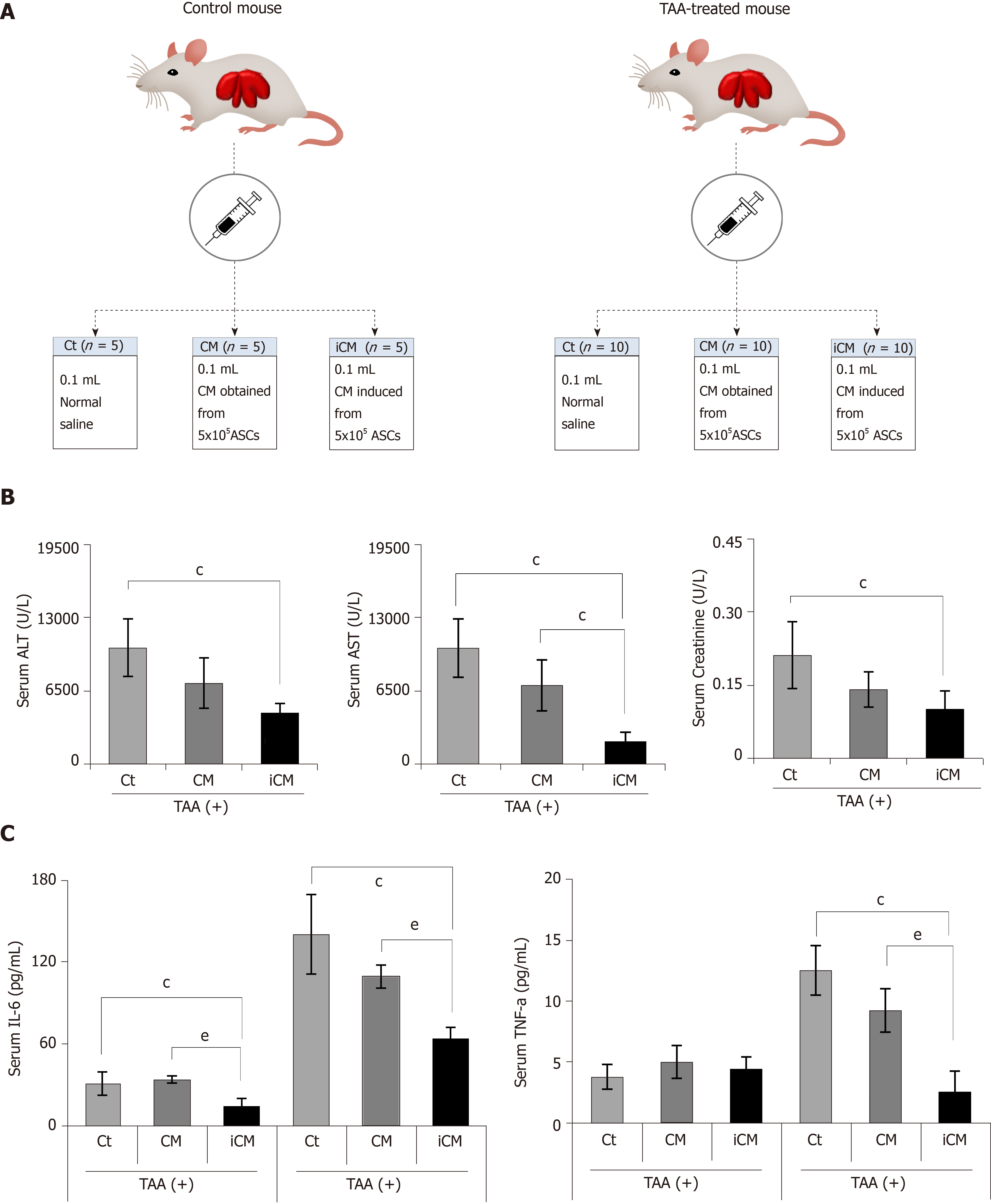

We then compared the effects of the TAA-isecretome in an in vivo model of TAA-induced hepatic failure. The in vivo model was generated by subcutaneous injection of TAA (300 mg/kg, 24-h intervals for 2 d) into experimental mice. Subsequently, control mice and TAA-treated mice were intravenously (using tail vein) infused with normal saline, CM, and iCM (Figure 3A). At 48 h after treatment, the mice were euthanized, and the specimens were investigated. Serologic tests showed that among these groups, iCM administration showed the greatest effects in lowering the serum levels of aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and creatinine in TAA-treated mice (Figure 3B). Similarly, ELISA showed that iCM administration decreased the serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in TAA-treated mice more than in the other groups (Figure 3C).

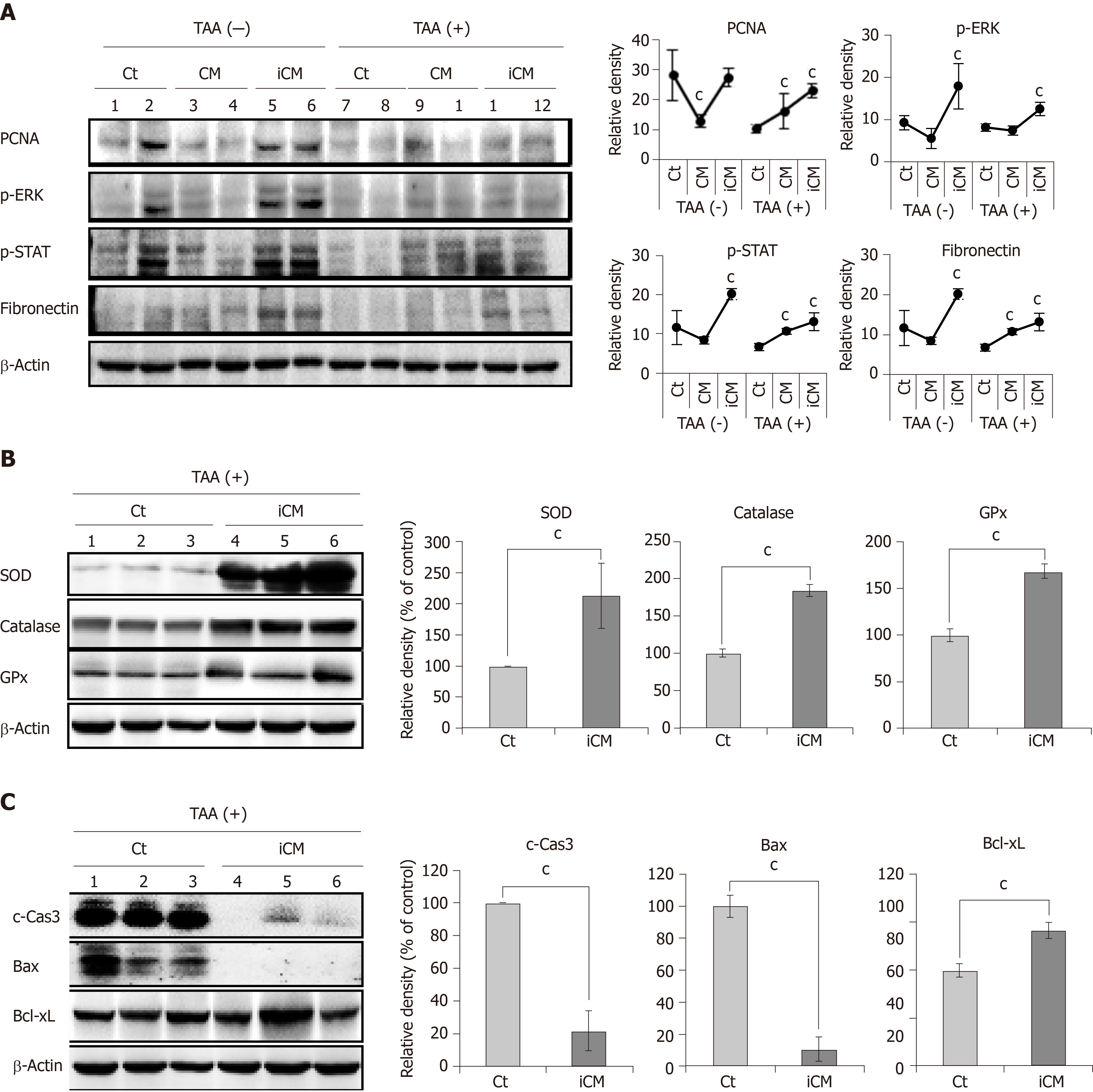

We performed western blot analysis to compare the expression of various markers reflecting liver regeneration and inflammation in the liver specimens of each group. iCM infusion caused the highest expression of PCNA, p-ERK, p-STAT, and fibronectin in both control livers and those of TAA-treated mice (Figure 4A). Additional western blot analysis showed that iCM infusion most significantly increased the expression of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, and GPx), and an antiapoptotic protein (Bcl-xL) and most significantly decreased the expression of proapoptotic proteins (c-caspase-3 and Bax) (Figure 4B and 4C).

iCM infusion most significantly decreased both liver-damage and kidney-damage scores that had been calculated based on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 5A). Further, immunohistochemical staining showed that iCM infusion most significantly decreased the expression of inflammatory markers (CD68 and PECAM) and most significantly increased the expression of albumin (Figure 5B).

To validate disease-specific effectiveness of the TAA-isecretome, we intravenously infused the TAA-isecretome into another model of liver injury, a mouse model of 70% partial hepatectomy. At 2 d after infusion, the mice were euthanized, and the specimens were investigated. Western blot analysis revealed that CM infusion, rather than TAA-iCM infusion, induced higher expression of proliferation markers (p-ERK and PCNA) and an antiapoptotic marker (Mcl-1) as well as lower expression of a proapoptotic marker (Bax). (Figure 6A). Taken altogether, the TAA-isecretome had the best proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in TAA-induced hepatic failure, indicating the potential for disease-specific treatment.

Various sets of isecretome specialized for individual diseases can be produced using corresponding disease-causing materials. We additionally generated an HBx-isecretome (HBx-iCM) using hepatitis X antigens as inducer and compared the components of the CM, TAA-iCM, and HBx-iCM using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS). Of the total proteins identified in the CM, TAA-iCM, and HBx-iCM, 32 secretory proteins were quite different according to each secretome (Figure 6B). Of them, we further investigated ten proteins that had been identified in TAA-iCM, but not in the CM. To predict affected pathways among the differentially expressed genes of the ten proteins, GO enrichment analysis were performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). GO enrichment analysis identified 19 enriched biological networks of the 10 proteins that had been exclusively identified in TAA-isecretome. Of the 19 enriched biological networks, the two most prominent biological processes were the response to reactive oxygen species and cell redox homeostasis, all of which were related with antioxidant activity. Of the ten proteins, peroxiredoxin-1 (Prdx-1) attracted our attention because it is known to have potent antioxidant activity (Figure 6C).

Prdx-1 exerts its antioxidant activity by catalyzing the reduction of H2O2 and alkyl hydroperoxide and thus protects cells from the attack of free radicals. Prdx-1 belongs to the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) ligand[23]. We thus compared the expression of a hepatoproliferative marker (p-ERK) according to the expression of Prdx-1 (Figure 6D). After treatment with the TAA-iCM, AML2 hepatocytes showed the higher expression of p-ERK as well as Prdx-1 compared with AML2 cells treated with the CM (P < 0.05). Subsequently, we compared the efficacy of the TAA-iCM after pre-treatment of TAK242, a TLR4 inhibitor. Pre-treatment of TAK242 did not only inhibit the expression of Prdx-1 but also inhibited the expression of p-ERK, the hepato-proliferative marker. Taken altogether, our results suggest that Prdx-1 is one of the essential components in TAA-iCM and plays a central role in the protection of TAA-induced hepatic injury.

In this study, we showed that the TAA-isecretome was superior to the naïve secretome in restoring hepatic function while minimizing inflammatory processes in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. Specifically, isecretome infusion showed higher therapeutic potential in terms of (1) Restoring disorganized hepatic tissue to normal tissue; (2) inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines; and (3) reducing abnormally elevated liver enzymes compared to naïve secretome infusion. The plasticity of MSCs in response to specific toxins may have led to the generation and secretion of protective agents (isecretome) against them. Our proteomic analysis indicated that the secretome components exhibited considerable differences according to the “inducing materials.” We expect that clinical application of this concept would be useful for overcoming a variety of diseases for which therapeutics have not been discovered.

Generally, cells have the propensity to protect themselves after exposure to detrimental stimuli or toxins. Because MSCs are unspecialized cells, they have higher plasticity and responsiveness than other cell types, i.e. they can either differentiate into specialized cells or release responsive materials more proficiently than differentiated cells depending on the external stimuli. Rodríguez-Suárez et al[18] investigated the proteome of EVs secreted by primary hepatocytes after exposure to well-known liver toxins (galactosamine and Escherichia coli-derived lipo-polysaccharide). EVs exposed to liver toxins contained higher levels of vital liver-specific proteins, such as carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1, S-adenosyl methionine synthetase 1, and catechol-O-methyltransferase compared to control EVs. The secretome composition is influenced by a variety of external factors, including the cell source, type of culture media, culturing period, and physicochemical environment. Vizoso et al[24] classified the external stimuli into four major categories: (1) Hypoxic preconditioning; (2) Pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as TNF-α, lipopolysaccharide, toll-like receptor agonists; (3) Three-dimensional growth, such as spheroid culture, which stimulates trophic factor secretion; and (4) Microparticle engineering, by which the release of a secretome is manipulated. Using the higher plasticity and responsiveness of MSCs, we induced a specific secretome specialized for treating a specific disease.

Whereas the secretome was obtained by nonspecific stimulation, the isecretome was obtained by using stimuli specific for individual diseases, allowing for disease-specific therapy. The isecretome for a specific disease is obtained by stimulating MSCs with specific pathogens involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. This concept is based on the superior responsiveness and plasticity of MSCs compared to host cells, which were exploited in several previous studies[25,26]. Prado et al[27] reported the successful prevention of allergic reaction by intranasal administration of EVs in a murine model of Ole e 1 (the main allergen of olive tree pollen)-allergic sensitization. The EVs were first obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in mice that had been exposed to Ole e 1. Their favorable results were based on the plasticity of mature respiratory cells. In contrast, our experiment is based on the plasticity of MSCs that are far higher than that of mature cells and demonstrated the increased therapeutic potential.

A prerequisite to obtaining a disease-specific secretome is to determine optimized conditions under which pathogenic materials appropriately induce MSCs to produce protective materials. Too strong or too weak stimulation of MSCs is undesirable because this can lead to either MSC damage or insufficient generation of the isecretome, respectively. To obtain the TAA-isecretome, we first collected the secretory materials from hepatocytes after treating the cells with a TAA, which were named as inducers. We then harnessed ASCs to release the isecretome by treating ASCs with inducers. For this, we determined (1) the concentration of TAA that both maximally stimulated and minimally damaged hepatocytes; and (2) the optimal dilution rate of inducers for harnessing ASCs to release the isecretome with maximal therapeutic potential. We validated this process by western blot analyses of markers reflecting the proliferation and apoptosis of cells.

The hepatotoxic effect of TAA is attributed to its metabolic intermediate, thioacetamide-S-oxide[28]. It is a free radical that binds to hepatic macromolecules, subsequently leading to necrosis of hepatocytes. Silymarin is one of the best known hepatoprotective drugs (the mechanism of action is largely dependent on its antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities)[29]. Throughout LC/MS analysis, we recognized ten proteins that had been exclusively identified in the TAA-iCM but not in the CM. GO enrichment analysis of these proteins found that antioxidant processes were the most predominant enriched biological networks. Of the ten proteins, Prdx-1 attracted our attention because it is known to have potent antioxidant activity.

Prdx-1 is an antioxidant enzyme belonging to the peroxiredoxin family of proteins. It has excellent antioxidant activity by catalyzing the reduction of H2O2 and alkyl hydroperoxide and thus protects cells from the attack of free radicals. In an experiment, Prdx-1 knockdown significantly increased the cellular levels of free radicals, while Prdx-1 overexpression reversed them[30]. Binding of Prdx-1 to TLR4 induced the release of numerous cytokines and growth factors, such as IL-6, TNF-α, and VEGF[23,31]. Moreover, we found that the inhibition of TLR4 by TAK242 (a TLR4 inhibitor) led to significant reduction in the expression of p-ERK (a proliferative marker) as well as Prdx-1. Taken altogether, our results suggest that Prdx-1 is one of the representative components released from ASCs that had been induced by TAA and plays a central role in the protection of TAA-induced hepatic injury.

The principle of generating the isecretome is similar to how antibodies against specific antigens are obtained in serotherapy. In serotherapy, introduction of attenuated antigens into the host induces the generation of antibodies against these antigens, which are collected to treat patients suffering from antigen-related disease. Similarly, in isecretome-based therapy, presensitization of MSCs with pathogens induced the generation of the secretome including protective agents against pathogens, which were collected to treat pathogen-causing disease. Because isecretome therapy provides a disease-specific approach, specific therapeutics can be developed based on high plasticity and responsiveness of MSCs. Further studies on the isecretome are expected to identify therapeutic materials by reproducing the pathogenesis of a certain disease within MSCs. There are numerous diseases for which therapeutics have not been developed or are ineffective. We presumed that MSCs can reproduce the repair materials against certain incurable illnesses when encountered during pathogenesis. There are two main clinical applications of the isecretome:1) direct utilization as therapeutic materials and 2) identification of more specific ingredients as therapeutic materials. The latter is accomplished by proteomic studies of isecretome components. Using isecretome-based technology, we could build “biological drug factories” based on the plasticity of MSCs that produce therapeutic materials from MSCs.

In conclusion, we showed that the TAA-isecretome was superior to the naïve secretome in restoring hepatic function while minimizing inflammatory processes in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. However, such superiority was not observed in the mouse model of partial hepatectomy. This suggests that the specific pathogen induces MSCs to release the secretome specialized for the pathogen. Free radicals are principal pathogenic agents in the pathogenesis of TAA-induced hepatic injury. LC/MS analysis and subsequent GO enrichment analysis of TAA-isecretome identified that antioxidant processes were the most predominantly enriched biological networks of the proteins exclusively identified in the TAA-isecretome. In addition, Prdx-1, a potent antioxidant protein, was found to be one of the representative components of the TAA-isecretome and played a central role in the protection of TAA-induced hepatic injury.

The exclusive use of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-secreted molecules, named as the secretome, rather than stem cells have been evaluated for overcoming the limitations of cell-based therapy while maintaining its advantages. As recent studies have shown that this secretome has therapeutic effects similar to stem cells, the secretome has become the basis of cell-free therapy.

The composition of the secretome is influenced by various external factors, including the cell source, type of culture media, culturing period, and preconditioning treatment. Previous studies suggest that MSCs can be induced to generate a specialized secretome customized to a specific disease. We herein defined induced secretome (isecretome) as the secretome released from MSCs that had been stimulated by disease-causing materials to treat the specific disease.

Thioacetamide (TAA) is a well-known hepatotoxin. We thus attempted to validate the higher therapeutic effects of the secretome induced by TAA (TAA-isecretome) compared to the naïve secretome, specifically in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. If the superiority of the isecretome over the naïve secretome is demonstrated, it could provide a foundation for producing a disease-specific isecretome applicable to specific diseases.

We collected the secretory materials (named as inducers) released from AML12 hepatocytes that had been pretreated with TAA and generated the TAA-isecretome after stimulating ASCs with the inducers. The TAA-isecretome was intravenously administered to mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure and those with partial hepatectomy. In addition, we generated an HBx-isecretome using hepatitis X antigens as inducers and compared the components of the naïve secretome, TAA-isecretome, and HBx-isecretome using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Compared to the naïve secretome infusion, TAA-isecretome infusion showed higher therapeutic potential in terms of (1) restoring disorganized hepatic tissue to normal tissue; (2) Inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α); and (3) Reducing abnormally elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. However, the TAA-isecretome showed inferior therapeutic potential for restoring hepatic function in partially hepatectomized mice. Proteomic analysis of the TAA-isecretome identified that antioxidant processes were the most predominant enriched biological networks of the proteins exclusively identified in the TAA-isecretome. In addition, peroxiredoxin-1, a potent antioxidant protein, was found to be one of the representative components of the TAA-isecretome.

We showed that the TAA-isecretome was superior to the naïve secretome in restoring hepatic function while minimizing inflammatory processes in mice with TAA-induced hepatic failure. However, such superiority was not observed in the mouse model of partial hepatectomy, suggesting disease-specificity of the TAA-isecretome. Free radicals are principal pathogenic agents in the pathogenesis of TAA-induced hepatic injury. Proteomic analysis of TAA-isecretome identified that antioxidant processes were the most predominantly enriched biological networks of the proteins exclusively identified in the TAA-isecretome. In addition, Prdx-1, a potent antioxidant protein, was found to be one of the representative components of the TAA-isecretome.

Our results suggest that appropriate stimulation of MSCs with pathogenic agents can lead to the production of a secretome specialized for protecting against the pathogen. This approach is expected to open a new way of developing various specific therapeutics based on the high plasticity and responsiveness of MSCs.

We would like to thank Drug and Disease Target Team (Ochang), Korea Basic Science Institute for supporting funds for this experiment. We would like to thank Hye-Jung Kim for photoshop work that improved the figure quality. We would like to thank Francis Sahngun Nahm (a professional statistician) for his devoted assistance of statistical analysis. Finally, we would like to thank Hye-Jeong Kim and Ji-Hye Park for data processing and photoshop work.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akiyama Y, Sundararajan V S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Lee SK, Lee SC, Kim SJ. A novel cell-free strategy for promoting mouse liver regeneration: utilization of a conditioned medium from adipose-derived stem cells. Hepatol Int. 2015;9:310-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Conci S, Valdegamberi A, Iacono C. How much remnant is enough in liver resection? Dig Surg. 2012;29:6-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | An SY, Jang YJ, Lim HJ, Han J, Lee J, Lee G, Park JY, Park SY, Kim JH, Do BR, Han C, Park HK, Kim OH, Song MJ, Kim SJ, Kim JH. Milk Fat Globule-EGF Factor 8, Secreted by Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Protects Against Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1174-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Miura M, Miura Y, Padilla-Nash HM, Molinolo AA, Fu B, Patel V, Seo BM, Sonoyama W, Zheng JJ, Baker CC, Chen W, Ried T, Shi S. Accumulated chromosomal instability in murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells leads to malignant transformation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1095-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3316] [Cited by in RCA: 3388] [Article Influence: 109.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tolar J, Nauta AJ, Osborn MJ, Panoskaltsis Mortari A, McElmurry RT, Bell S, Xia L, Zhou N, Riddle M, Schroeder TM, Westendorf JJ, McIvor RS, Hogendoorn PC, Szuhai K, Oseth L, Hirsch B, Yant SR, Kay MA, Peister A, Prockop DJ, Fibbe WE, Blazar BR. Sarcoma derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thomson BM, Bennett J, Dean V, Triffitt J, Meikle MC, Loveridge N. Preliminary characterization of porcine bone marrow stromal cells: skeletogenic potential, colony-forming activity, and response to dexamethasone, transforming growth factor beta, and basic fibroblast growth factor. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1173-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang Y, Huso DL, Harrington J, Kellner J, Jeong DK, Turney J, McNiece IK. Outgrowth of a transformed cell population derived from normal human BM mesenchymal stem cell culture. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:509-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Götherström C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, Ringdén O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2044] [Cited by in RCA: 2031] [Article Influence: 96.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baglio SR, Pegtel DM, Baldini N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front Physiol. 2012;3:359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:244-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 595] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1645] [Cited by in RCA: 1545] [Article Influence: 90.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hoch AI, Binder BY, Genetos DC, Leach JK. Differentiation-dependent secretion of proangiogenic factors by mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang Z, Di Santo S, Kalka C. Current developments in the use of stem cell for therapeutic neovascularisation: is the future therapy "cell-free"? Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee SC, Jeong HJ, Lee SK, Kim SJ. Hypoxic Conditioned Medium From Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Promotes Mouse Liver Regeneration Through JAK/STAT3 Signaling. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:816-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee SC, Kim KH, Kim OH, Lee SK, Hong HE, Won SS, Jeon SJ, Choi BJ, Jeong W, Kim SJ. Determination of optimized oxygen partial pressure to maximize the liver regenerative potential of the secretome obtained from adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee SC, Jeong HJ, Lee SK, Kim SJ. Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning of adipose-derived stem cells improves liver-regenerating activity of the secretome. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rodríguez-Suárez E, Gonzalez E, Hughes C, Conde-Vancells J, Rudella A, Royo F, Palomo L, Elortza F, Lu SC, Mato JM, Vissers JP, Falcón-Pérez JM. Quantitative proteomic analysis of hepatocyte-secreted extracellular vesicles reveals candidate markers for liver toxicity. J Proteomics. 2014;103:227-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Keppler D, Lesch R, Reutter W, Decker K. Experimental hepatitis induced by D-galactosamine. Exp Mol Pathol. 1968;9:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen S, Liu C, Wang X, Li X, Chen Y, Tang N. 15-Deoxy-Δ(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) promotes apoptosis of HBx-positive liver cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;214:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Galanos C, Lüderitz O, Rietschel ET, Westphal O, Brade H, Brade L, Freudenberg M, Schade U, Imoto M, Yoshimura H. Synthetic and natural Escherichia coli free lipid A express identical endotoxic activities. Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Choi CW, Park EC, Yun SH, Lee SY, Lee YG, Hong Y, Park KR, Kim SH, Kim GH, Kim SI. Proteomic characterization of the outer membrane vesicle of Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4298-4309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Riddell JR, Wang XY, Minderman H, Gollnick SO. Peroxiredoxin 1 stimulates secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by binding to TLR4. J Immunol. 2010;184:1022-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 881] [Article Influence: 110.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zipori D. Mesenchymal stem cells: harnessing cell plasticity to tissue and organ repair. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33:211-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jiang Y, Vaessen B, Lenvik T, Blackstad M, Reyes M, Verfaillie CM. Multipotent progenitor cells can be isolated from postnatal murine bone marrow, muscle, and brain. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:896-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Prado N, Marazuela EG, Segura E, Fernández-García H, Villalba M, Théry C, Rodríguez R, Batanero E. Exosomes from bronchoalveolar fluid of tolerized mice prevent allergic reaction. J Immunol. 2008;181:1519-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Staňková P, Kučera O, Lotková H, Roušar T, Endlicher R, Cervinková Z. The toxic effect of thioacetamide on rat liver in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24:2097-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ghosh S, Sarkar A, Bhattacharyya S, Sil PC. Silymarin Protects Mouse Liver and Kidney from Thioacetamide Induced Toxicity by Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species and Activating PI3K-Akt Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chae S, Lee HK, Kim YK, Jung Sim H, Ji Y, Kim C, Ismail T, Park JW, Kwon OS, Kang BS, Lee DS, Bae JS, Kim SH, Min KJ, Kyu Kwon T, Park MJ, Han JK, Kwon T, Park TJ, Lee HS. Peroxiredoxin1, a novel regulator of pronephros development, influences retinoic acid and Wnt signaling by controlling ROS levels. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Riddell JR, Bshara W, Moser MT, Spernyak JA, Foster BA, Gollnick SO. Peroxiredoxin 1 controls prostate cancer growth through Toll-like receptor 4-dependent regulation of tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1637-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |