Published online Jul 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4484

Peer-review started: January 31, 2021

First decision: March 29, 2021

Revised: April 9, 2021

Accepted: July 12, 2021

Article in press: July 12, 2021

Published online: July 28, 2021

Processing time: 175 Days and 20.3 Hours

It is often difficult to explain why ulcerative lesions are found in the small intestine because there are no obvious aggressors such as gastric acid. In particular, the treatment of small intestinal ulcerative lesions in asymptomatic patients with no symptoms, normal physical examinations, and normal blood test findings is not well documented. According to a summary of capsule endoscopy studies in healthy subjects, approximately 10% of subjects have small intestinal mucosal breaks. The number of mucosal breaks in these instances is approximately 1-3. We examined small intestinal mucosal breaks in healthy subjects recruited from our past two studies. Mucosal breaks were observed in approximately 10% of subjects, and the average number was 0.24 ± 1.21. The number of mucosal breaks in the small intestine was correlated with body mass index and was significantly higher in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects and higher in males. These results indicate that 1-2 small ulcerative lesions, such as erosions in the small intestine, can be considered to be in the normal range, and close examination is not required. It is assumed that a follow-up medical examination is required for such asymptomatic persons. The presence of many small ulcerative lesions or an unequivocal ulcer indicates an abnormality for which close examination is desired. However, in many cases, it is sufficient to scrutinize after detecting anemia, but it is difficult to make a judgment due to insufficient reports, and future studies are required.

Core Tip: Approximately 10% of asymptomatic subjects with normal blood tests have small intestinal mucosal breaks. A reanalysis of our previous studies showed that small intestinal mucosal breaks were strongly correlated with body mass index, were significantly more prevalent in Helicobacter pylori-infected individuals and were more prevalent in men. These may be risk factors for small intestinal mucosal breaks. Overall, 1-2 small ulcerative lesions in asymptomatic patients are considered to be in the normal range and do not require close examination, and it is assumed that a follow-up medical examination is required.

- Citation: Fujimori S. Asymptomatic small intestinal ulcerative lesions: Obesity and Helicobacter pylori are likely to be risk factors. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(28): 4484-4492

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i28/4484.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4484

Ulcerative lesions are less common in the small intestine, except in the duodenum, than in the stomach. Even if some small ulcerative lesions such as erosions are found in the stomach, we do not care much because of the many accumulated reports and experiences. However, we are concerned with the cause of ulcerative lesions of the small intestine. This is because the small intestine lacks obvious aggressors such as gastric acid, making it difficult to explain the cause of ulcerative lesions. Moreover, there is insufficient knowledge about ulcerative lesions of the small intestine.

Screening colonoscopy occasionally detects a small number of small ulcerative lesions at the terminal ileum. Patients with small ulcerative lesions at the terminal ileum who do not take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often doubtful about Crohn's disease (CD) in endoscopic results reports. Some patients had small ulcerative lesions that could potentially progress to CD, and a case was reported[1]. Recently, a report described that CD was detected in 0.28% (13 out of 4640 cases) by colorectal cancer screening[2]. The report indicated that ileal ulcers were detected in 6 of 13 cases, suggesting that ileal ulcers were associated with CD. Four of the 6 patients had no lesions other than ileal ulcers, and the simple endoscopic score for CD was 2-6 points. In other words, some patients had a slightly larger ileal ulcer; however, all patients were scheduled only for a followed up without treatment. It is considered difficult to make an endoscopic diagnosis of the 4 patients with CD, and it is not stated whether granuloma was detected by histological examination. The diagnosis of CD is difficult in the early stages, but the patients in this study did not appear to meet the diagnostic criteria for CD[3]. The question remains as to the diagnosis of CD in these patients, and the follow-up results are considered important.

Subjects who were asymptomatic with no abnormalities in blood tests or physical tests and were not taking medication were defined as healthy subjects. This may include patients with asymptomatic diseases; however, these were subjects without any obvious disease. It is not easy to frequently follow-up with an endoscopy for asymptomatic small ulcerative lesions of the small intestine identified the screening test of healthy subjects because of the physical and financial burdens imposed on the subject. In addition, even if an asymptomatic small ulcerative lesion is found at the terminal ileum, it is considered to be rare and not enough reason to conduct close examination, such as capsule endoscopy. However, it is not clear whether this research policy is correct. This is because the treatment of small intestinal ulcerative lesions in asymptomatic patients is not reported. This is thought to be because reports on the proportion of ulcerative lesions in the small intestine found in healthy subjects and the cause of small intestinal ulcerative lesions are extremely few. In this paper, we summarize how many small intestinal ulcerative lesions are found in healthy subjects, analyze the degree of appearance of small intestinal ulcerative lesions, and investigate the causes of small intestinal ulcerative lesions where possible. Then, we would like to consider the research policy when small intestinal ulcerative lesions are found.

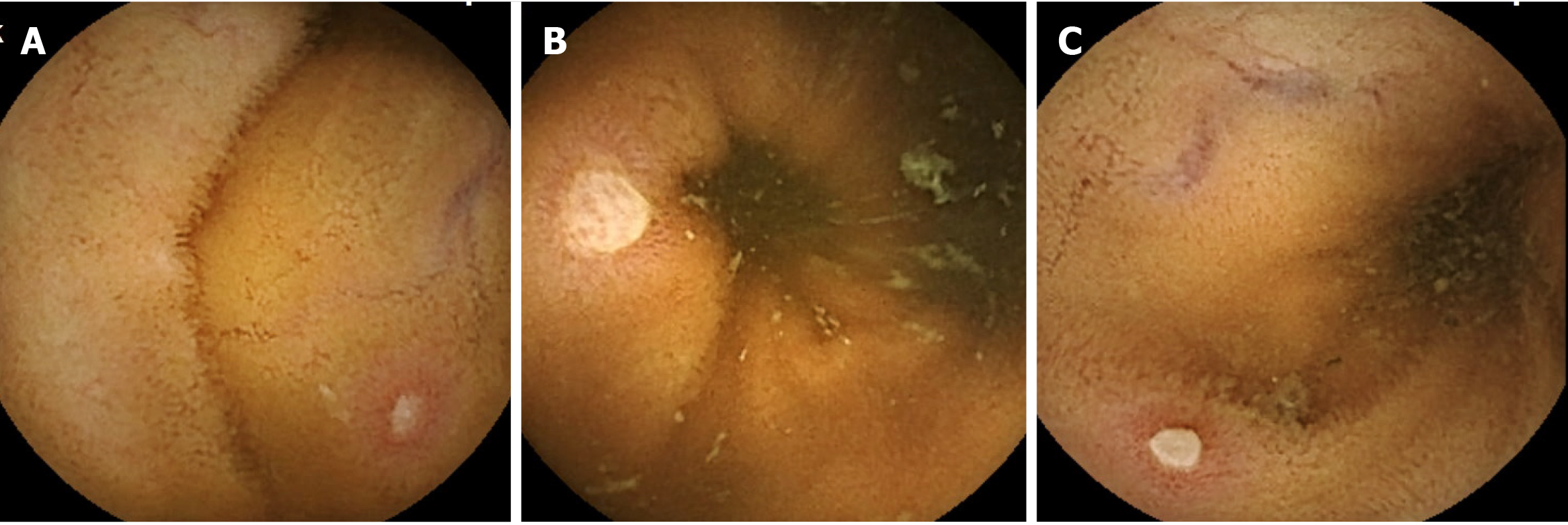

Ulcerative lesions of the small intestine are often evaluated as mucosal breaks. A mucosal break is a lesion in which white slough is observed, and the degree varies from small ulcerative lesion erosion (Figure 1A) to ulcer (Figure 1B). It is difficult to clearly distinguish this lesion, and there are many cases in which it is not clear which category a specific lesion should be classified into, as shown in Figure 1C. This ulcerative lesion has white slough over 3 mm and approximately 5 mm. Since it is expected that the judgments by researchers will be different in categorizing this lesion, the frequency of appearance of mucosal breaks of healthy subjects was analyzed here.

In many studies, nonselective NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase 2-selective NSAIDs are administered to healthy subjects to compare the occurrence of small intestinal mucosal breaks. There are other studies in which mucosal protective drugs are administered at the same time as NSAIDs and aspirin to compare the effects of this combination. Capsule endoscopy has been performed in more than 1000 healthy subjects in various studies. In these studies, healthy subjects underwent capsule endoscopy before drug administration, and small intestinal evaluation of the healthy subjects was performed first. Table 1 summarizes the studies describing small intestinal mucosal breaks in healthy subjects before drug administration. Studies that do not describe these premedication small intestinal mucosal breaks and reports with a small number of subjects were not included in the Table 1.

| Country | Year | No. | Subjects with mucosal breaks | Mean number of mucosal breaks | Ref. | ||

| Number | % | Subjects with MB | All subjects | ||||

| United States | 2005 | 413 | 571 | 13.81 | N/A | N/A | Goldstein et al[10], 2005 |

| United States | 2007 | 472 | 56 | 11.9 | N/A | N/A | Goldstein et al[11], 2007 |

| Japan | 2009 | 32 | 3 | 9.4 | 1.7 | 0.16 | Fujimori et al[12], 2009 |

| Canada | 2009 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Smecuol et al[13], 2009 |

| Japan | 2010 | 20 | 2 | 10.0 | 1-2 | 0.1-0.2 | Shiotani et al[14], 2010 |

| Japan | 2011 | 72 | 4 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 0.56 | Fujimori et al[4], 2011 |

| Japan | 2013 | 32 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.1-0.3 | Kuramoto et al[15], 2013 |

| China | 2014 | 30 | 2 | 6.7 | 3.5 | 0.23 | Huang et al[16], 2014 |

| Japan | 2014 | 30 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.14 ± 0.54 | Umegaki et al[17], 2014 |

| Japan | 2016 | 141 | 14 | 9.9 | 3.5 | 0.35 | Fujimori et al[5], 2016 |

| Japan | 2015 | 37 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.1-0.3 | Kojima et al[18], 2015 |

| Czech | 2016 | 42 | 2 | 4.7 | N/A | N/A | Tachecí et al[19], 2016 |

| Japan | 2016 | 19 | 2 | 10.5 | 1.0 | 0.11 | Arimoto et al[20], 2016 |

| Japan | 2016 | 45 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.13 | Ota et al[21], 2016 |

| Japan | 2019 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ota et al[22], 2019 |

According to the summarized results, approximately 10% of healthy subjects have small intestinal mucosal breaks. In addition, the number of mucosal breaks in subjects with mucosal breaks was approximately 1-3 in most examinations.

Our group has conducted several capsule endoscopy studies on healthy subjects. Two of these consisted of detailed tests and interviews, including tests for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection which bacterium is known to cause gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, atrophic gastritis, gastric cancer, etc., at the start of the study. Since the number of subjects in each study was insufficient for analysis, we combined these two studies to analyze the background of healthy subjects. In two studies we tested for H. pylori infection with a breath test[4] and with serum antibodies[5] prior to the NSAID dosing experiment. In particular, the latter study was investigated to block randomize H. pylori-infected individuals evenly when randomized.

Table 2 shows the cases that were analyzed. The total number of cases included in the two studies was slightly higher than that shown in Table 1. This is because the first capsule endoscopy was completed, but the subjects who dropped out of the study were added. The subjects enrolled in the study were those who were considered to be healthy subjects after screening, the results of basic blood tests and physical tests were normal, and were not taking any medication. The number of mucosal breaks in the small intestine determined by capsule endoscopy in these healthy subjects was 0.24 ± 1.21 (mean ± SD). Based on these results, if the average ± 2 SD of healthy subjects is considered to be the normal range, up to 2 mucosal breaks of the small intestine are in the normal range.

Next, since the number of mucosal breaks recognized in the subjects was 1-2 in most cases, subjects were divided into 21 cases with mucosal breaks and 201 cases without mucosal breaks. Then, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol consumption, and H. pylori infection were compared and analyzed. The results of the univariate analysis showed that the incidence of mucosal breaks was higher in men, in subjects that had a higher BMI, and in H. pylori-infected subjects. Therefore, when multivariate analysis was performed with these factors, mucosal breaks were strongly correlated with BMI and were significantly more common in H. pylori-infected subjects (Table 3).

The results of this analysis revealed that small intestinal mucosal breaks were correlated with BMI. In many reports, it has been reported that obese people have different intestinal flora compared to those with proper weight. Additionally, specific bacteria, which are predominantly present in obese people, cause tight junctions in the intestinal tract to malfunction allowing bacterial products to pass through the intestinal wall[6]. The results of the analysis are considered to support this idea. High-fat diet also affects gut flora[7]. In addition, blood flow disorders due to arteriosclerosis and lack of exercise may be involved.

In addition, small intestinal mucosal breaks was higher in H. pylori-infected subjects. We do not consider H. pylori-infected subjects to be completely healthy individuals, so H. pylori infection was investigated prior to the capsule endoscopy study to evenly distribute H. pylori-infected subjects between the two groups in our previous study[5]. The results of this study support the idea that H. pylori infection also affects the small intestine. Currently, it is easy to understand that the reason why H. pylori-infected individuals have many small intestinal mucosal breaks is that H. pylori infection causes atrophic gastritis, which is caused by changes in the intestinal flora due to a decrease in gastric acid concentration. Experimental reports of exacerbation of NSAID ulcers by administration of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely known[8]. Since the bacterial cell components and bacterial products of H. pylori flow in the lumen of the small intestine and their involvement is doubtful, such examination may be necessary in the future.

In addition, small intestinal mucosal breaks tended to be higher in men. We were doubtful that smoking and alcohol consumption were related to mucosal breaks and no relationship was found between them in the analysis. CD is more common in men, and men may have some sex differences that are more likely to cause ulcerative lesions in the small intestine.

Any obvious ulcer should be considered abnormal. Table 4 summarizes the diseases and causes that cause small intestinal ulcers. Although it is not possible to mention the ulcer size here, it is natural to consider even one ulcer that is considered to be large or deep, such as white slough exceeding 1 cm, to be abnormal. However, what should we think of a small mucosal break with white slough up to approximately 5 mm?

| Category | Disease and/or cause | Ref. |

| Inflammatory disease | Crohn’s disease | Gomollón et al[3], 2017 |

| Behçet's disease | Lee et al[23], 2012 | |

| polyarteritis nodosa | Perlemuter et al[24], 1996 | |

| Schönlein-Henoch purpura | Nishiyama et al[25], 2008 | |

| Vascular disease | Ischemic enteritis | Iwai et al[26], 2018 |

| Systemic disease | Amyloidosis | Tada et al[27], 1994 |

| Heridetary disease | Chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 gene | Umeno et al[28], 2015 |

| Bacterial infection | Yersinia enterocolitica | Matsumoto et al[29], 1990 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Duffy et al[30], 1980 | |

| Salmonella typhi | Goel et al[31], 2017 | |

| Salmonella typhmurium | Boyd[32], 1985 | |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Dworkin et al[33], 2001 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Lu et al[34], 2020 | |

| Viral infection | Epstein-Barr virus | Watanabe et al[35], 2020 |

| Cytomegalovirus | Matsumura et al[36], 2020 | |

| COVID-19 | Sahu et al[37], 2021 | |

| Drug induced | Various drugs included NSAIDs | Scarpignato and Bjarnason[38], 2019 |

| Immunodeficiency | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | Zeitz et al[39], 1998 |

| Graft-versus-host disease | Peled et al[40], 2016 |

As mentioned above, nearly 10% of healthy people have 1-2 small mucosal breaks. It would be physically and economically burdensome to follow-up with a capsule endoscopy for a person with a small number of asymptomatic mucosal breaks. Among the subjects examined in this study (Table 2), there were 3 male subjects with 5 or more mucosal breaks, but it was only confirmed at the end of the study that there were no abnormal symptoms or abnormal blood data. On the other hand, there is a case report in which a PPI was administered to a patient who had 6 mucosal breaks by capsule endoscopy before the study, and an increase in mucosal breaks was confirmed[9]. No abnormalities were found in this subject at a follow-up examination 2 years after the study.

If 3 or more small mucosal breaks are found in the small intestine, it is considered to exceed ± 2 SD on average and should be judged to be out of the normal range. There is a possibility that some of these asymptomatic lesions may develop into other diseases, such as CD, but there are few reports at this time, and there is not enough information to consider follow-up guidelines. Considering the financial and physical burden of capsule endoscopy, it cannot be stated in detail how many mucosal breaks warrant followed-up, so presently the decision is left to each medical professional. Therefore, we think it is appropriate to perform a re-examination with a capsule endoscopy, etc., when anemia or similar symptoms appear during follow-up at a normal health examination.

Based on this analysis, approximately 10% of healthy individuals have small intestinal mucosal breaks, and high BMI, H. pylori-infected individuals, and men are more likely to present with mucosal breaks. When up to 2 small mucosal breaks of 5 mm or less are found, this is considered to be within the normal range; therefore, asymptomatic persons with mucosal breaks could be followed up at a normal annual health examination. When a person has 3 or more small mucosal breaks, it is considered to be out of the normal range, but presently a follow-up schedule cannot be considered due to insufficient information. Nevertheless, when there is no significant number of mucosal breaks, follow-up should be carried out at a normal medical examination, and if anemia occurs, a close examination policy is sufficient. When a patient has an obvious ulcer, abnormality exists; therefore, close examination is desired. However, there is not enough information at this time to consider how to treat asymptomatic small intestinal ulcers.

We also hope that it should be clarified in future whether H. pylori and BMI really affect small intestinal ulcerative lesions in healthy subjects. 16s rRNA or metabolite sequencing of the intestinal flora between H. pylori-infected and uninfected as well as between high- and low-BMI assess whether small intestinal ulcerative lesions correlate with changes in the microbial flora. These researches such as comparing the intestinal flora of objects is considered necessary. Future studies are required to address this issue.

I would like to thank the individuals who coauthored the manuscripts referenced in this paper with me and the research assistants who helped with those studies.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Gastroenterological Association, No. 326349; and The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology, No. 020689.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Farhat S, Hu Y S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Sorrentino D, Avellini C, Geraci M, Vadalà S. Pre-clinical Crohn's disease: diagnosis, treatment and six year follow-up. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:702-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bezzio C, Manes G, Schettino M, Arena I, de Nucci G, Della Corte C, Devani M, Mandelli E, Morganti D, Omazzi B, Pellegrini L, Picascia D, Redaelli D, Reati R, Saibeni S. Inflammatory bowel disease in a colorectal cancer screening population: Diagnosis and follow-up. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1585] [Cited by in RCA: 1449] [Article Influence: 181.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fujimori S, Takahashi Y, Gudis K, Seo T, Ehara A, Kobayashi T, Mitsui K, Yonezawa M, Tanaka S, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Rebamipide has the potential to reduce the intensity of NSAID-induced small intestinal injury: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial evaluated by capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fujimori S, Hanada R, Hayashida M, Sakurai T, Ikushima I, Sakamoto C. Celecoxib Monotherapy Maintained Small Intestinal Mucosa Better Compared With Loxoprofen Plus Lansoprazole Treatment: A Double-blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dabke K, Hendrick G, Devkota S. The gut microbiome and metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:4050-4057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang M, Yang XJ. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8905-8909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wallace JL, Syer S, Denou E, de Palma G, Vong L, McKnight W, Jury J, Bolla M, Bercik P, Collins SM, Verdu E, Ongini E. Proton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dysbiosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1314-1322.e1-1322.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fujimori S, Takahashi Y, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Omeprazole increased small intestinal mucosal injury in two of six disease-free cases evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:676-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Zlotnick S, Fort JG; Investigators. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, Berger MF. Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1211-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K, Ehara A, Kobayashi T, Mitsui K, Yonezawa M, Tanaka S, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-intestinal injury by prostaglandin: a pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Smecuol E, Pinto Sanchez MI, Suarez A, Argonz JE, Sugai E, Vazquez H, Litwin N, Piazuelo E, Meddings JB, Bai JC, Lanas A. Low-dose aspirin affects the small bowel mucosa: results of a pilot study with a multidimensional assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:524-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shiotani A, Haruma K, Nishi R, Fujita M, Kamada T, Honda K, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Graham DY. Randomized, double-blind, pilot study of geranylgeranylacetone versus placebo in patients taking low-dose enteric-coated aspirin. Low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel damage. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kuramoto T, Umegaki E, Nouda S, Narabayashi K, Kojima Y, Yoda Y, Ishida K, Kawakami K, Abe Y, Takeuchi T, Inoue T, Murano M, Tokioka S, Higuchi K. Preventive effect of irsogladine or omeprazole on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced esophagitis, peptic ulcers, and small intestinal lesions in humans, a prospective randomized controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang C, Lu B, Fan YH, Zhang L, Jiang N, Zhang S, Meng LN. Muscovite is protective against non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small bowel injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11012-11018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Umegaki E, Kuramoto T, Kojima Y, Nouda S, Ishida K, Takeuchi T, Inoue T, Tokioka S, Higuchi K. Geranylgeranylacetone, a gastromucoprotective drug, protects against NSAID-induced esophageal, gastroduodenal and small intestinal mucosal injury in healthy subjects: A prospective randomized study involving a comparison with famotidine. Intern Med. 2014;53:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kojima Y, Takeuchi T, Ota K, Harada S, Edogawa S, Narabayashi K, Nouda S, Okada T, Kakimoto K, Kuramoto T, Inoue T, Higuchi K. Effect of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and healing effect of irsogladine on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-intestinal lesions in healthy volunteers. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2015;57:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tachecí I, Bradna P, Douda T, Baštecká D, Kopáčová M, Rejchrt S, Lutonský M, Soukup T, Bureš J. Wireless Capsule Enteroscopy in Healthy Volunteers. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2016;59:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arimoto J, Endo H, Kato T, Umezawa S, Fuyuki A, Uchiyama S, Higurashi T, Ohkubo H, Nonaka T, Takeno M, Ishigatsubo Y, Sakai E, Matsuhashi N, Nakajima A. Clinical value of capsule endoscopy for detecting small bowel lesions in patients with intestinal Behçet's disease. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ota K, Takeuchi T, Nouda S, Ozaki H, Kawaguchi S, Takahashi Y, Harada S, Edogawa S, Kojima Y, Kuramoto T, Higuchi K. Determination of the adequate dosage of rebamipide, a gastric mucoprotective drug, to prevent low-dose aspirin-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2016;59:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ota K, Takeuchi T, Kojima Y, Harada S, Hirata Y, Sugawara N, Nouda S, Kakimoto K, Kuramoto T, Higuchi K. Preventive effect of ecabet sodium on low-dose aspirin-induced small intestinal mucosal injury: a randomized, double-blind, pilot study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee HJ, Kim YN, Jang HW, Jeon HH, Jung ES, Park SJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Nam CM, Cheon JH. Correlations between endoscopic and clinical disease activity indices in intestinal Behcet's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5771-5778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Perlemuter G, Chaussade S, Soubrane O, Degoy A, Louvel A, Barbet P, Legman P, Kahan A, Weiss L, Couturier D. Multifocal stenosing ulcerations of the small intestine revealing vasculitis associated with C2 deficiency. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1628-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nishiyama R, Nakajima N, Ogihara A, Oota S, Kobayashi S, Yokoyama K, Oonishi M, Miyamoto S, Akai Y, Watanabe T, Uno A, Mizuno S, Ootani T, Tanaka N, Moriyama M. Endoscope images of Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Digestion. 2008;77:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Iwai N, Handa O, Naito Y, Dohi O, Okayama T, Yoshida N, Kamada K, Uchiyama K, Ishikawa T, Takagi T, Konishi H, Itoh Y. Stenotic Ischemic Enteritis with Concomitant Hepatic Portal Venous Gas and Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis. Intern Med. 2018;57:1995-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tada S, Iida M, Yao T, Kawakubo K, Okada M, Fujishima M. Endoscopic features in amyloidosis of the small intestine: clinical and morphologic differences between chemical types of amyloid protein. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:45-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Umeno J, Hisamatsu T, Esaki M, Hirano A, Kubokura N, Asano K, Kochi S, Yanai S, Fuyuno Y, Shimamura K, Hosoe N, Ogata H, Watanabe T, Aoyagi K, Ooi H, Watanabe K, Yasukawa S, Hirai F, Matsui T, Iida M, Yao T, Hibi T, Kosaki K, Kanai T, Kitazono T, Matsumoto T. A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the SLCO2A1 Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin Transporter. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Matsumoto T, Iida M, Matsui T, Sakamoto K, Fuchigami T, Haraguchi Y, Fujishima M. Endoscopic findings in Yersinia enterocolitica enterocolitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:583-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Duffy MC, Benson JB, Rubin SJ. Mucosal invasion in campylobacter enteritis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1980;73:706-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Goel A, Bansal R. Massive Lower Gastrointestinal Bleed caused by Typhoid Ulcer: Conservative Management. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2017;7:176-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Boyd JF. Pathology of the alimentary tract in Salmonella typhimurium food poisoning. Gut. 1985;26:935-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Goldoft MJ, Kobayashi JM. Reactive arthritis and Reiter's syndrome following an outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by Salmonella enteritidis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1010-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lu S, Fu J, Guo Y, Huang J. Clinical diagnosis and endoscopic analysis of 10 cases of intestinal tuberculosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Watanabe H, Yamazaki Y, Fujishima F, Ohashi Y, Imoto H, Sasano H. Epstein-Barr virus-associated enteritis with multiple ulcers: The first autopsy case. Pathol Int. 2020;70:899-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Matsumura M, Komeda Y, Watanabe T, Kudo M. Purpura-free small intestinal IgA vasculitis complicated by cytomegalovirus reactivation. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sahu T, Mehta A, Ratre YK, Jaiswal A, Vishvakarma NK, Bhaskar LVKS, Verma HK. Current understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on gastrointestinal disease: Challenges and openings. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:449-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Scarpignato C, Bjarnason I. Drug-Induced Small Bowel Injury: a Challenging and Often Forgotten Clinical Condition. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zeitz M, Ullrich R, Schneider T, Kewenig S, Hohloch K, Riecken EO. HIV/SIV enteropathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;859:139-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Peled JU, Hanash AM, Jenq RR. Role of the intestinal mucosa in acute gastrointestinal GVHD. Blood. 2016;128:2395-2402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |