Published online May 28, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i20.2657

Peer-review started: January 25, 2021

First decision: February 27, 2021

Revised: March 9, 2021

Accepted: May 7, 2021

Article in press: May 7, 2021

Published online: May 28, 2021

Processing time: 115 Days and 2.5 Hours

Although cyclophosphamide (CPA) is the key drug for the treatment of autoimmune diseases including vasculitides, it has some well-known adverse effects, such as myelosuppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, infertility, and infection. However, CPA-associated severe enteritis is a rare adverse effect, and only one case with a lethal clinical course has been reported. Therefore, the appropriate management of patients with CPA-associated severe enteritis is unclear.

We present the case of a 61-year-old woman diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis based on the presence of symptoms in ear, lung, and, kidney with positive myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. She received pulsed methylprednisolone followed by prednisolone 55 mg/d and intravenous CPA at a dose of 500 mg/mo. Ten days after the second course of intravenous CPA, she developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and was admitted to the hospital. Laboratory testing revealed hypoalbuminemia, suggesting protein-losing enteropathy. Computed tomography revealed wall thickening of the stomach, small intestine, and colon with contrast enhancement on the lumen side. Antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapy were not effective, and the patient’s enteritis did not improve for > 4 mo. Because her condition became seriously exhausted, corticosteroids were tapered and supportive therapies including intravenous hyperalimentation, replenishment of albumin and gamma globulin, plasma exchange, and infection control were continued. These supportive therapies improved her condition, and her enteritis gradually regressed. She was finally discharged 7 mo later.

Immediate discontinuation of CPA and intensive supportive therapy are crucial for the survival of patients with CPA-associated severe enteritis.

Core Tip: Cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis is rare, but a fatal complication of the treatment for the vasculitides. This is the first successful report of the treatment for the severe cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis, and indicates the importance of immediate discontinuation of cyclophosphamide and intensive supportive therapy.

- Citation: Sato H, Shirai T, Fujii H, Ishii T, Harigae H. Cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis presenting with severe protein-losing enteropathy in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(20): 2657-2663

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i20/2657.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i20.2657

Cyclophosphamide (CPA) is an alkylating agent that is frequently used in vasculitides as an induction therapy. Particularly in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, the addition of immunosuppressants is recommended for patients with a higher five-factor score[1]. CPA is metabolized into the active form in the liver and covalently binds to the nucleus[2]. Thereafter, it manifests antiproliferative effects by inhibiting deoxyribonucleic acid replication[2]. Although CPA has an established therapeutic effect in vasculitides, it sometimes results in adverse effects including myelosuppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, increased susceptibility to infection, and infertility[3]. However, the development of enteritis due to CPA use in patients with autoimmune diseases is rare, with only one case report in which Yang et al[4] presented a lethal case of CPA-associated enteritis in a patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Here, we report a severe case of CPA-associated enteritis in a patient who presented with prominent protein-losing enteropathy, who was successfully treated with supportive therapy including plasma exchange (PE).

A 61-year-old Japanese woman developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Three months before the first admission, she experienced nasal congestion, aural fullness, and auditory disturbance, and was diagnosed with otitis media. Also, two months before presentation, she experienced cough worsening, and chest radiography revealed a pulmonary infiltrative shadow. Two months before presentation, she was referred to our hospital for the evaluation of pulmonary consolidation with positive myeloperoxidase-ANCA (MPO-ANCA). She was admitted to the previous hospital. She had a body temperature of 38 °C and elevated C-reactive protein level (7.7 mg/dL). Although she was treated with antibiotics, her symptoms, inflammatory markers, and chest infiltrates did not improve. Laboratory examination showed a high titer of MPO-ANCA (Table 1), and she was referred to our hospital. After admission, her creatinine level increased with proteinuria, glomerular hematuria, and granular casts, indicating the presence of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN). Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed on the basis of the presence of otitis media, sinusitis, pulmonary nodule, RPGN, and positive MPO-ANCA. She received pulsed methylprednisolone followed by prednisolone (PSL) 55 mg/d in combination with intravenous CPA at a dose of 500 mg/mo. Her condition significantly improved, and she was discharged 9 d after the second course of intravenous CPA when the PSL dose was 45 mg/d. She developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea the day after discharge, and was admitted to our hospital.

| First admission | Second admission | |

| Urinalysis | ||

| Protein | 1+ | 2+ |

| Occult blood | 1+ | - |

| Red blood cell | 10-29/HPF1 | < 4/HPF |

| Casts | +2 | +3 |

| Spot protein-creatinine ratio (g/g Cr) | 0.38 | 0.20 |

| WBC (/µL) | 14500 | 6100 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.9 | 14.9 |

| Plt (104/µL) | 43.4 | 35.1 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| AST (U/L) | 25 | 20 |

| ALT (U/L) | 30 | 18 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 24 | 18 |

| ALP (U/L) | 239 | 102 |

| LDH (U/L) | 207 | 200 |

| CK (U/L) | 58 | 37 |

| TP (g/dL) | 7.1 | 4.3 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 11 | 35 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 14.2 | 0.2 |

| MPO-ANCA (U/mL) | 194.0 | 1.0 |

She had been diagnosed with Grave’s disease since the age of 40.

The patient had no family history.

On admission, her consciousness was clear, body temperature was 36.3 °C, and body pressure was 106/75 mmHg. Her abdomen was soft and flat, with pain in the left lower quadrant without defense or rebound tenderness.

Laboratory testing indicated hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia, suggesting protein-losing enteropathy that resulted in the leakage of proteins from the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1).

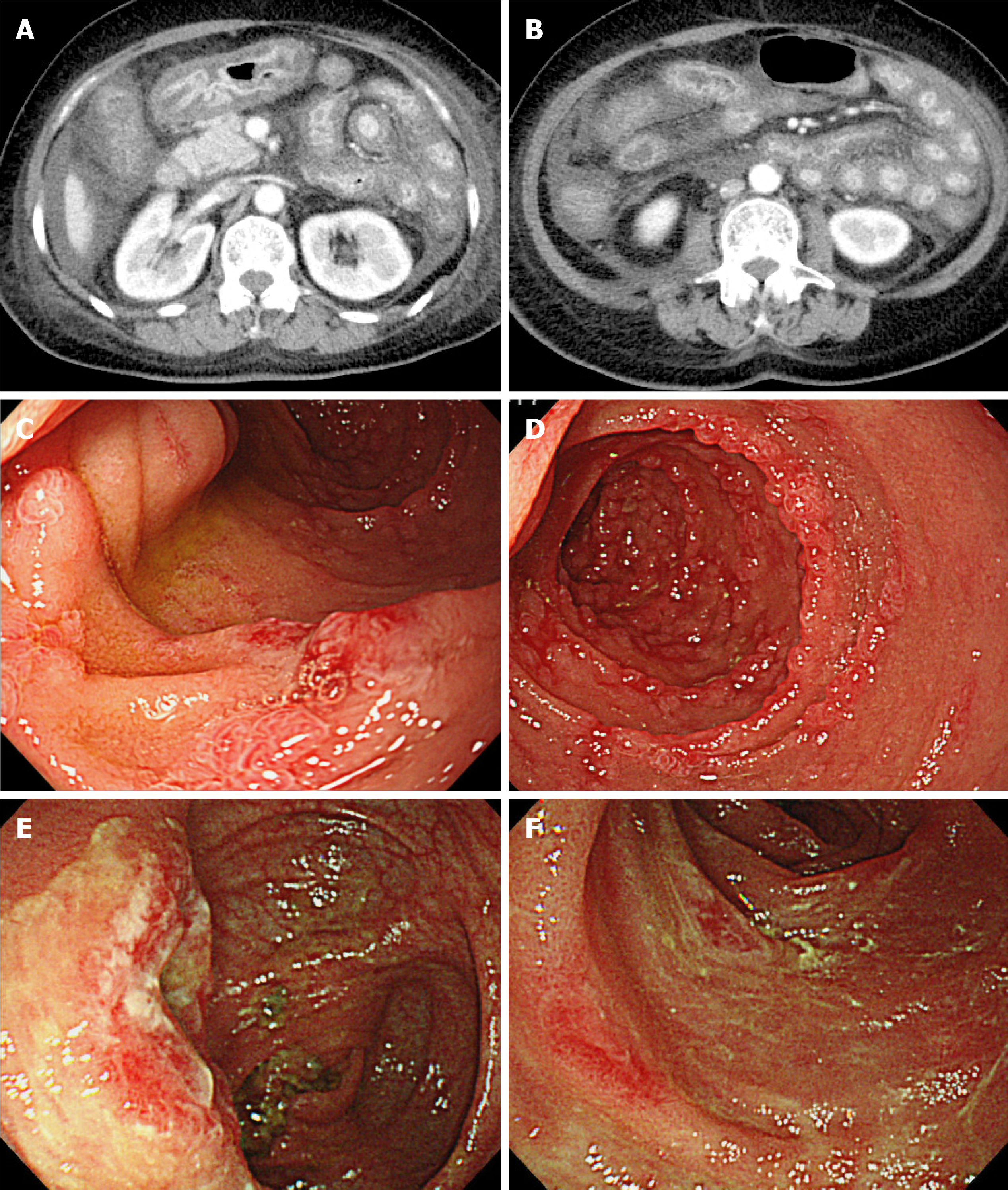

Abdominal radiography did not show niveau or free air. Computed tomography (CT) revealed wall thickening of the stomach, small intestine, and colon with contrast enhancement on the lumen side (Figure 1A). The contrast enhancement of the outer layer of the intestine was poor, indicating edematous change. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed edematous thickening of the stomach and diffusely distributed erosion throughout the descending duodenum (Figure 1B). Colonoscopy showed generalized edema and depression with erythema, mainly at the end of the ileum. The depression had no ulcerated surface.

Biopsy showed the absence of malignancy and vasculitis, as well as neoplastic changes including hyperplasia. Mild inflammatory cellular infiltration and some granulation tissues and ulcers were present. Cytomegalovirus staining was negative. Because the differential diagnoses included infectious enteritis, GPA-associated gastroenteritis, and drug-induced enteritis, the patient was initially treated with antibiotics including meropenem. However, hypoalbuminemia progressed. Therefore, we replenished albumin and gamma globulin and performed PE. Her condition did not improve, and her serum albumin levels remained approximately 1.5 mg/dL for > 1 mo. This clinical course ruled out the presence of an infectious etiology. Therefore, we decided to augment immunosuppression, and increased the PSL dose to 60 mg/d and added tacrolimus. Nevertheless, the enteritis did not respond to these treatments, which was contradictory to the autoimmune phenomenon, including GPA-associated enteritis. At this point, infectious and vasculitic etiologies were unlikely.

The CPA-associated enteropathy was considered, as previously reported by Yang et al[4].

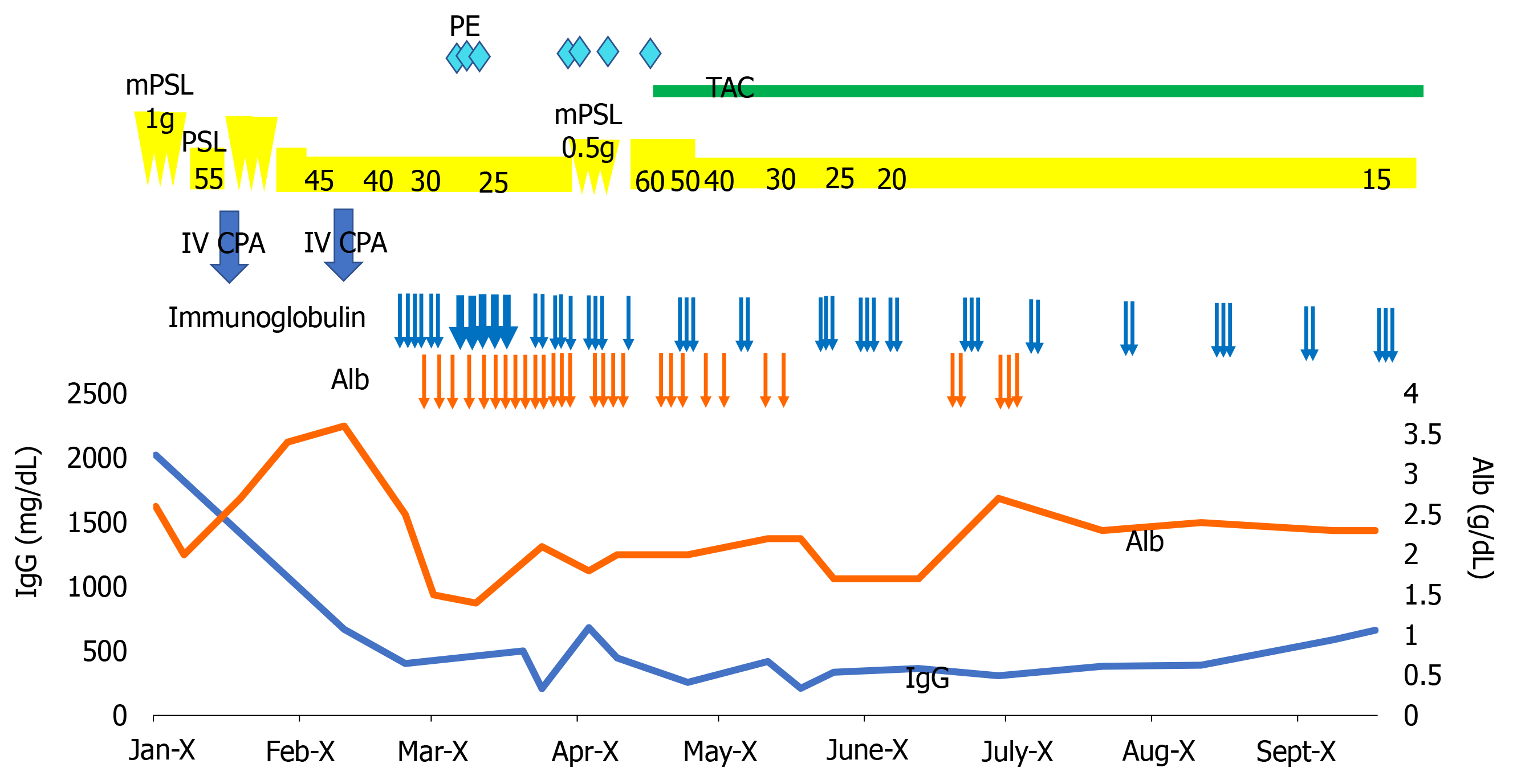

Because her condition became seriously exhausted, we tapered the steroid dose and continued supportive therapy including intravenous hyperalimentation, albumin supplementation, PE, and infection control (Figure 2).

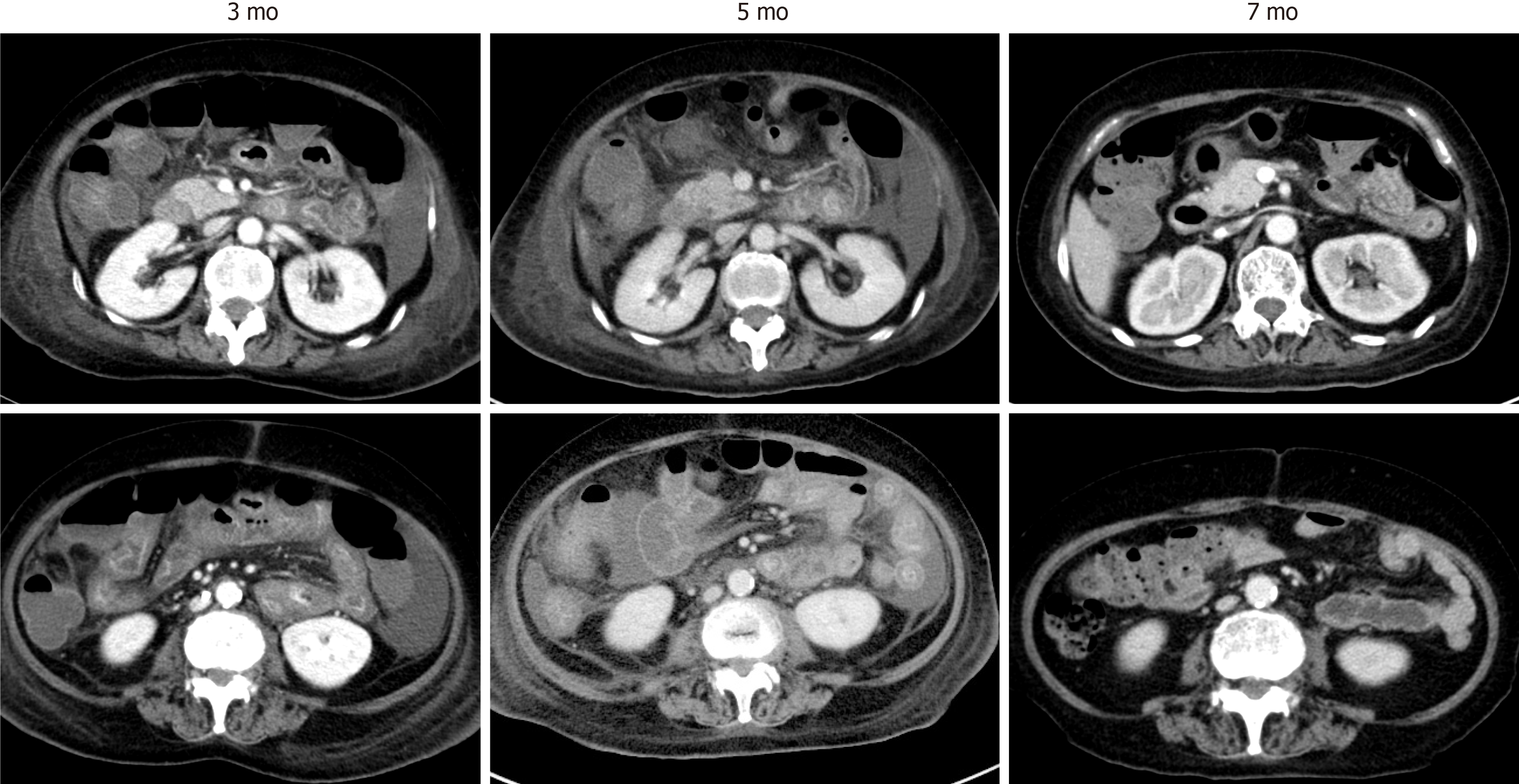

The supportive therapies improved the patient’s condition, and her enteritis gradually regressed (Figure 3). She was finally discharged 7 mo after the second admission and underwent rehabilitation. At 2 years from discharge, she is now in complete remission and has returned to her previous work.

The present case was complicated with severe enteritis, which was considered to be an adverse effect of CPA. Although the patient had severe protein-losing enteropathy, her condition was improved by aggressive supportive therapies with repeated administrations of albumin and globulin for several months.

CPA is one of the frequently used immunosuppressant drugs for vasculitidis. Gastrointestinal involvement of GPA is one of the conditions requiring CPA[5]. However, CPA-associated enteritis is very rare, and there exists only one case describing a lethal course in a patient with GPA[4].

When the present patient manifested abdominal symptoms, her vasculitis was in remission, which was supported by the absence of ear symptoms, normal urinalysis, normal inflammatory marker levels, and negative MPO-ANCA. In addition, there were no histologic signs of vasculitis, granulomatous colitis, or gastritis in biopsy tissues. Further, treatment with immunosuppressants did not improve her condition, which was similar to the previously described case[4,6-8]. In addition, the blood culture, fecal culture, Clostridium difficile toxin, and cytomegalovirus tests were all negative. Because it was possible that these test results were false negative, antibiotics were administered, which did not improve the enteritis.

The mechanisms by which CPA causes enteritis are not well defined. In the field of oncology, CPA is likely to be associated with gastrointestinal involvement and mucositis, which may be related to the gut microbiota[9]. In a mouse model, Viaud et al[10] reported that CPA altered the microbiota composition in the small intestine and induced the translocation of selected species of gram-positive bacteria into secondary lymphoid organs.

We compared the clinical characteristics between the present case and the previous case. In the present case, symptoms appeared 38 d after the first intravenous CPA (500 mg/mo), whereas the previous case showed symptoms 2 wk after the start of oral CPA (100 mg/d). Therefore, the cumulative dose of CPA at the onset of symptoms was 1 g in the present case and 1.4 g in the previous case. Gastrointestinal lesions were distributed in the stomach, duodenum, small bowel, and colon in the present case, whereas they were limited to the small bowel and colon in the previous case. In the present case, CT showed massive wall thickening with prominent contrast enhancement in the mucosa. The outer layer showed edematous thickening. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed edematous thickening of the stomach and diffusely distributed erosion throughout the descending duodenum. Colonoscopy showed generalized edema from the transverse colon to the rectum. The clinical imaging findings in the previous case were similar to the diffuse mural thickening on CT and denuded and erythematous mucosa on endoscopy in the present case.

The difference from the previous report was that the present patient survived with intensive supportive therapy. In the previous case, CPA was continued for 1 mo with reduction to 50 mg/d after the complication of enteritis appeared, and then stopped. Therefore, the patient received 2.1 g CPA in total. In the present case, intravenous CPA was immediately stopped after the development of abdominal symptoms and the patient received 1 g CPA in total. Whether the cumulative dose of CPA influences the length of enteritis is uncertain, but the lower total CPA dose may be one of the reasons for the survival of the present patient. Nonetheless, this case confirmed that enteritis could develop not only with oral administration but also with intravenous injection of CPA.

With respect to treatment, no specific therapy exists for CPA-induced enteritis. However, the associated tissue injury is severe and can last for months, resulting in the loss of serum proteins including albumin and gamma globulin. Therefore, aggressive supportive therapies including hyperalimentation, replenishment of albumin and gamma globulin, and PE in severe cases are important. Because continuation of CPA is difficult in patients who experienced CPA-induced enteritis, rituximab or azathioprine can be the alternative treatment for GPA.

In conclusion, severe enteritis is a rare but life-threatening adverse effect of CPA. Immediate discontinuation of CPA and persistent supportive treatment are crucial for survival.

The authors thank the staff of the department of hematology and rheumatology, Tohoku University, for helpful discussions.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abe Y, Mattar MC, Rawat K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Seror R, Mahr A, Mouthon L, Toumelin PL; French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG). The Five-Factor Score revisited: assessment of prognoses of systemic necrotizing vasculitides based on the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG) cohort. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:19-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 595] [Cited by in RCA: 619] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Jonge ME, Huitema AD, Rodenhuis S, Beijnen JH. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:1135-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahmed AR, Hombal SM. Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan). A review on relevant pharmacology and clinical uses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:1115-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yang LS, Cameron K, Papaluca T, Basnayake C, Jackett L, McKelvie P, Goodman D, Demediuk B, Bell SJ, Thompson AJ. Cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis: A rare association with severe enteritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8844-8848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haworth SJ, Pusey CD. Severe intestinal involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis. Gut. 1984;25:1296-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Eriksson P, Segelmark M, Hallböök O. Frequency, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome of Gastrointestinal Disease in Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis and Microscopic Polyangiitis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:529-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chow FY, Hooke D, Kerr PG. Severe intestinal involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:749-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Müller-Ladner U. Vasculitides of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:59-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu T, Wu Y, Wang L, Pang X, Zhao L, Yuan H, Zhang C. A More Robust Gut Microbiota in Calorie-Restricted Mice Is Associated with Attenuated Intestinal Injury Caused by the Chemotherapy Drug Cyclophosphamide. mBio. 2019;10:e02903-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Viaud S, Saccheri F, Mignot G, Yamazaki T, Daillère R, Hannani D, Enot DP, Pfirschke C, Engblom C, Pittet MJ, Schlitzer A, Ginhoux F, Apetoh L, Chachaty E, Woerther PL, Eberl G, Bérard M, Ecobichon C, Clermont D, Bizet C, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Cerf-Bensussan N, Opolon P, Yessaad N, Vivier E, Ryffel B, Elson CO, Doré J, Kroemer G, Lepage P, Boneca IG, Ghiringhelli F, Zitvogel L. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science. 2013;342:971-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1147] [Cited by in RCA: 1542] [Article Influence: 128.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |