Published online Feb 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.837

Peer-review started: October 14, 2018

First decision: November 14, 2018

Revised: January 11, 2019

Accepted: January 26, 2019

Article in press: January 26, 2019

Published online: February 21, 2019

Processing time: 134 Days and 1.2 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent condition. It is diagnosed on the basis of chronic symptoms after the clinical and/or investigative exclusion of organic diseases that can cause similar symptoms. There is no reproducible non-invasive test for the diagnosis of IBS, and this raises diagnostic uncertainty among physicians and hinders acceptance of the diagnosis by patients. Functional gastrointestinal (GI) syndromes often present with overlapping upper and lower GI tract symptoms, now believed to be generated by visceral hypersensitivity. This study examines the possibility that, in IBS, a nutrient drink test (NDT) provokes GI symptoms that allow a positive differentiation of these patients from healthy subjects.

To evaluate the NDT for the diagnosis of IBS.

This prospective case-control study compared the effect of two different nutrient drinks on GI symptoms in 10 IBS patients (patients) and 10 healthy controls (controls). The 500 kcal high nutrient drink and the low nutrient 250 kcal drink were given in randomized order on separate days. Symptoms were assessed just before and at several time points after drink ingestion. Global dyspepsia and abdominal scores were derived from individual symptom data recorded by two questionnaires designed by our group, the upper and the general GI symptom questionnaires, respectively. Psycho-social morbidity and quality of life were also formally assessed. The scores of patients and controls were compared using single factor analysis of variance test.

At baseline, IBS patients compared to controls had significantly higher levels of GI symptoms such as gastro-esophageal reflux (P = 0.05), abdominal pain (P = 0.001), dyspepsia (P = 0.001), diarrhea (P = 0.001), and constipation (P = 0.001) as well as higher psycho-social morbidity and lower quality of life. The very low incidence of GI symptoms reported by control subjects did not differ significantly for the two test drinks. Compared with the low nutrient drink, IBS patients with the high nutrient drink had significantly more dyspeptic symptoms at 30 (P = 0.014), 45 (P = 0.002), 60 (P = 0.001), and 120 min (P = 0.011). Dyspeptic symptoms triggered by the high nutrient drink during the first 120 min gave the best differentiation between healthy controls and patients (area under receiver operating curve of 0.915 at 45 min for the dyspepsia score). Continued symptom monitoring for 24 h did not enhance separation of patients from controls.

A high NDT merits further evaluation as a diagnostic tool for IBS.

Core tip: There is no objective non-invasive test for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. This study shows that measurement of early gastrointestinal symptoms provoked by ingestion of a caloric drink is a promising diagnostic tool for this syndrome. This test could allay patient and doctor uncertainty and reduce the use of costly and invasive diagnostic tests.

- Citation: Estremera-Arevalo F, Barcelo M, Serrano B, Rey E. Nutrient drink test: A promising new tool for irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(7): 837-847

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i7/837.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i7.837

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects about 15% of the population and is a common cause for medical consultation[1-3]. IBS is diagnosed when symptoms meet diagnostic criteria (the most authoratative currently being the Rome IV criteria), and clinical assessment and investigations do not reveal any other cause[4,5]. Diagnosis of IBS by exclusion is a burden for both physicians and patients, as this approach raises uncertainty as to its accuracy[6]. Clinical judgement is needed to determine the extent of investigations.

Overlap of IBS with functional dyspepsia (FD) is well-known, and in both, symptoms are believed to be due to visceral hypersensitivity[7]. Increased sensitivity to rectal barostatic balloon distension correlates with IBS severity, and this has been proposed as a reliable objective test for visceral hypersensitivity[8-10]. However, it is a specialised, invasive procedure. The provocation of symptoms by a nutrient drink test (NDT) has been found to be a useful, simple approach for diagnosis of FD[11]. Its value for IBS diagnosis has not been explored, even though the onset of IBS symptoms is frequently related to food intake via unknown mechanisms[12,13].

This case-control, prospective study, carried out in a tertiary center, explored the diagnostic potential of the NDT for diagnosis of IBS by evaluating symptoms after both high nutrient (HN) and low nutrient (LN) drinks in 10 IBS patients and 10 healthy control subjects.

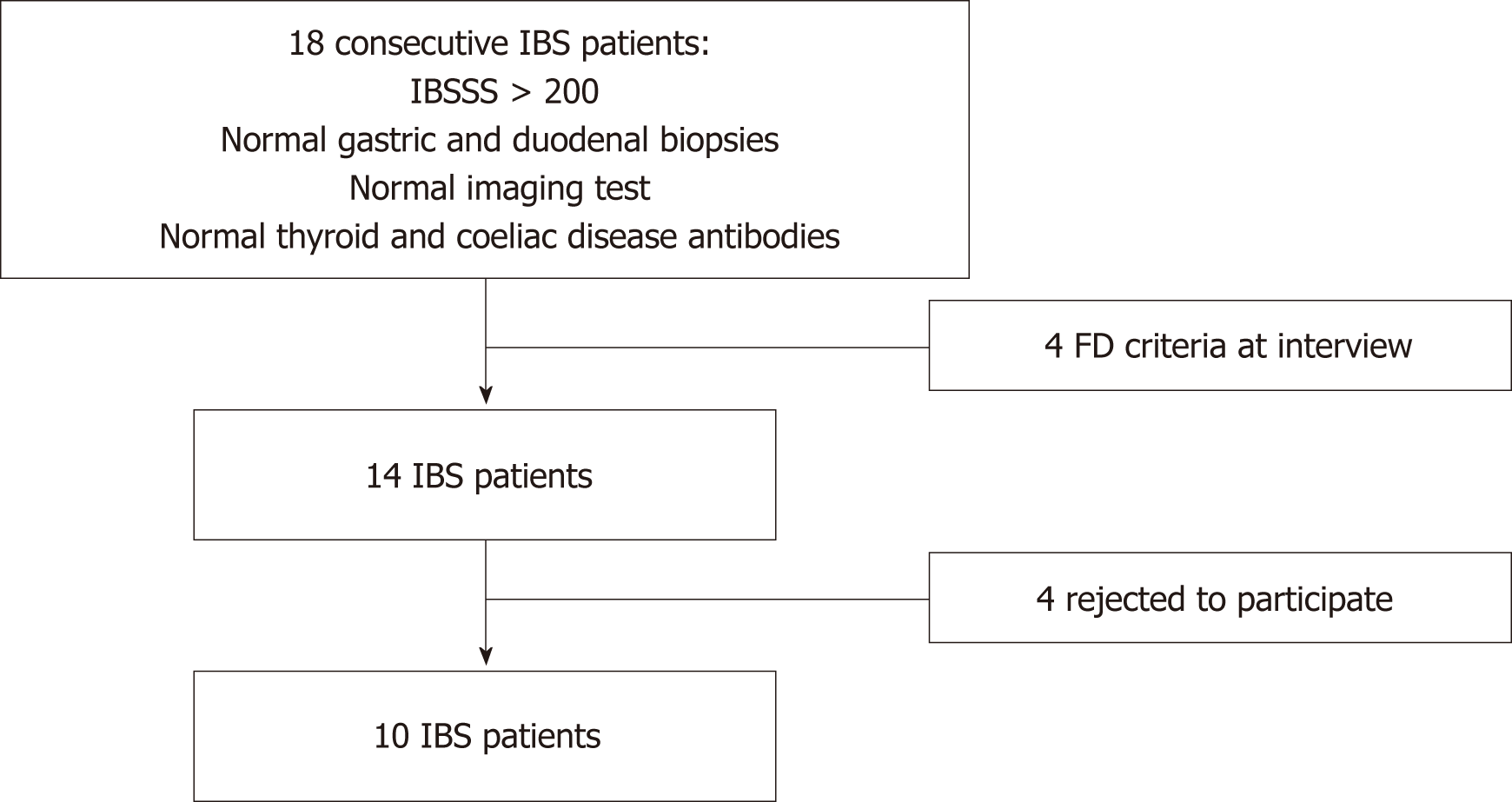

Gastrointestinal (GI) or metabolic diseases were excluded in all of the IBS patients by upper and lower GI endoscopy (with duodenal and gastric biopsies), imaging, and blood screens, which included thyroid hormone levels and celiac disease antibodies. IBS patients were enrolled only if they fulfilled the Rome III criteria for IBS and scored > 200 points in the irritable bowel severity scoring system (IBSSS) score[5,14]. IBS patients who also had gastro-esophageal reflux disease with adequate control of symptoms with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) were not excuded. Patients with FD were identified and excluded by a gastroenterologist interview, based on the Rome III criteria[4]. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of patient recruitment. The 10 healthy asymptomatic control subjects, who were recruited via advertisement in the gastroenterology hospital ward, were matched with the IBS patients for gender, age, and same category of body mass index.

Major exclusion criteria were FD, a history of abdominal surgery (except appendectomy and hysterectomy), and intake of drugs that can modify GI transit (e.g., opioids).

All participants gave informed consent after a careful explanation of the methods and objectives of this study. The project was named “Utilidad del test de saciedad precoz (“NDT”) para el diagnóstico de síndrome de intestino irritable”, and the study protocol satisfied the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clinico San Carlos on 15 February 2010 (local registry number 10/057-E).

All subjects received the HN and LN drinks within 10 d. Each matched pair of IBS and control subjects was randomized to one of two groups receiving either the HN or LN drink first. The HN drink, or NDT, was 500 mL of vanilla taste Ensure™ (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, United States), at the recommended dilution. This delivered 500 kcal was 86.5 g of carbohydrate (containing 5 g of fructooligosaccharide), 12.5 g of fat, and 19 g of protein. The 500 mL LN drink was a commercial vanilla drink (Okey Vainilla, Idilia Foods, Valencia, Spain) of similar flavor and color to the HN drink, diluted with water. This provided 250 kcal, consisting of 70 g of carbohydrate (with no fructooligosaccharide), 4.5 g of fat, and 12 g of protein. The drinks were consumed over 33 min (15 mL/min), similar to previous NDT studies[15,16].

Both drinks were given in the early morning after an 8 h fast. Subjects were blinded as to which drink they were receiving, but usually noticed that the drinks had different viscosities. Due to the circumstances of the study, the main investigator could not be blinded to drink type.

During the first study visit, a gastroenterologist made a detailed symptom and health background assessment. Following this, all subjects completed the following screening self-administered questionnaires to record their symptoms, quality of life (QOL), and psycho-social profiles in the prior 4 wk: Rome III criteria (symptoms related to different functional GI disorders), gastrointestinal symptoms rating scale (which measures different general GI symptoms with a Likert scale), symptom checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R, psychological health status), hospital anxiety and depression scale (regarding anxiety and depression related to physical symptoms), short form 12 (SF-12, health-related QOL), and IBSSS[4,14,17-19,20]. These questionnaires were completed during and after the first drink intake.

Two different questionnaires with 0-5 Likert scales (0: none; 1: very mild; 2: mild; 3: moderate; 4: severe; 5: very severe) were designed by our group for gathering symptoms present just before and at intervals after drink ingestion (see below). Symptoms were described similarly to wordings of the GERD-Q (Spanish validated version)[21], Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index, and IBSSS instruments[14,22]. Subjects reported their symptom levels to the investigator face to face within the first 2 h and then by telephone for the rest of the 24 h after the start of the drink. The Global Dyspepsia Score, which evaluated satiety, nausea, epigastric distension, epigastric pain, heartburn, and regurgitation, was completed just before the drink, then every 5 min during ingestion, and then at 45, 60, and 120 min. The Global Dyspepsia Score at each assessment time was the sum of all of the symptom scores gathered over the previous 5 min by the Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms Questionnaire. The General Gastrointestinal Symptom Questionnaire evaluated the following symptoms for 24 h after the drinks: Heartburn, regurgitation, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, bowel actions and stool type according to the Bristol scale[23], stool urgency, and presence of mucus in the stool. This second questionnaire was completed at the start of the drink and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h after ingestion. The global abdominal score was derived for each assessment time by summing the scores for the individual symptoms evaluated in the General Gastrointestinal Symptom Questionnaire. After ingestion of the test drinks, participants were encouraged to eat a free diet, except for avoiding vegetable fiber and alcoholic drinks during the next 24 h.

Demographics of patients and control subjects and the screening questionnaire scores were compared by One-Way analysis of variance. Symptom scores during and after the two drinks were compared with analysis of variance for repeated measures. The discriminatory capacity of the NDT was evaluated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (SPSS 16.0 version, Chicago, IL, United States). The difference was considered statistically significant when P < 0. 05.

The mean values for IBS patients (nine female, one male) and their matched healthy controls did not differ significantly for age and body mass index. Five patients had alternating IBS (IBS-A), and five had diarrhea IBS. One of the patients had gastro-esophageal reflux disease, controlled by PPI.

For 4 wk prior to testing, the IBS patients had high levels of GI symptoms compared to controls (Table 1). Though they did not report clinically significant dyspeptic symptoms in the screening clinical interview, 4/10 IBS patients fulfilled FD diagnostic criteria in the self-administered Rome III questionnaire completed after study entry. GER, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and constipation scores were derived from the gastrointestinal symptoms rating scale and the IBSSS from the sum of its five variables (abdominal pain, number of days with pain, abdominal distension, disordered bowel habit, and QOL burden). All of the 4 wk baseline scores before the first drink were significantly higher in the patients (Table 1).

| Control | IBS | P value | |

| GER | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 1.4 | 0.05 |

| Abdominal pain | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 1.7 | 0.001 |

| Dyspepsia | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 0.3 ±0.7 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 0.001 |

| Constipation | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 0.001 |

| IBSSS score | 37.3 ± 36.0 | 275.3 ± 115.6 | 0.001 |

Compared to controls, the scores derived from the SCL-90 and HAD for IBS patients demonstrated substantially higher psycho-social morbidity for most of the variables assessed (Table 2). QOL was also significantly impaired in IBS patients in both the mental (P = 0.001) and physical (P = 0.000) domains (Table 2).

| Control | IBS | P value | |

| Somatization1 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Obsession1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.004 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity1 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.05 |

| Depression1 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety1 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 0.005 |

| Hostility1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.09 |

| Phobic anxiety1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.05 |

| Paranoid ideation1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.025 |

| Psychoticism1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.013 |

| Positive global symptoms1 | 17.2 ± 13.3 | 46.0 ± 21.7 | 0.002 |

| Distress index1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.002 |

| HAD anxiety | 3.6 ± 2.0 | 11.1 ± 4.8 | 0.000 |

| HAD depression | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 5.4 | 0.01 |

| HAD score | 5.1 ± 2.6 | 17.8 ± 9.6 | 0.000 |

| Physical score2 | 55.0 ± 5.0 | 37.4 ± 11.7 | 0.000 |

| Mental score2 | 53.9 ± 6.0 | 42.3 ± 11.6 | 0.001 |

All participants consumed all of the HN and LN drinks.

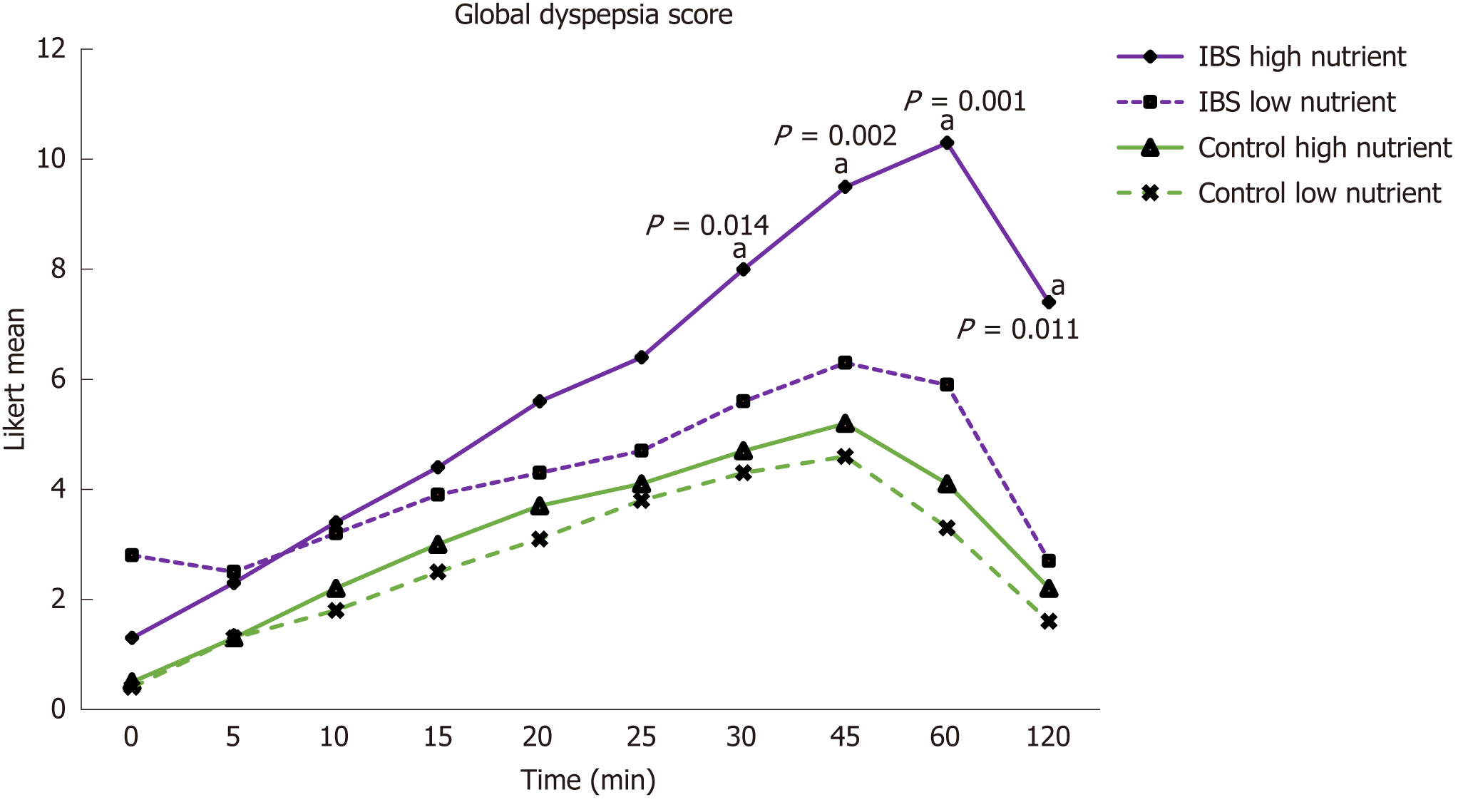

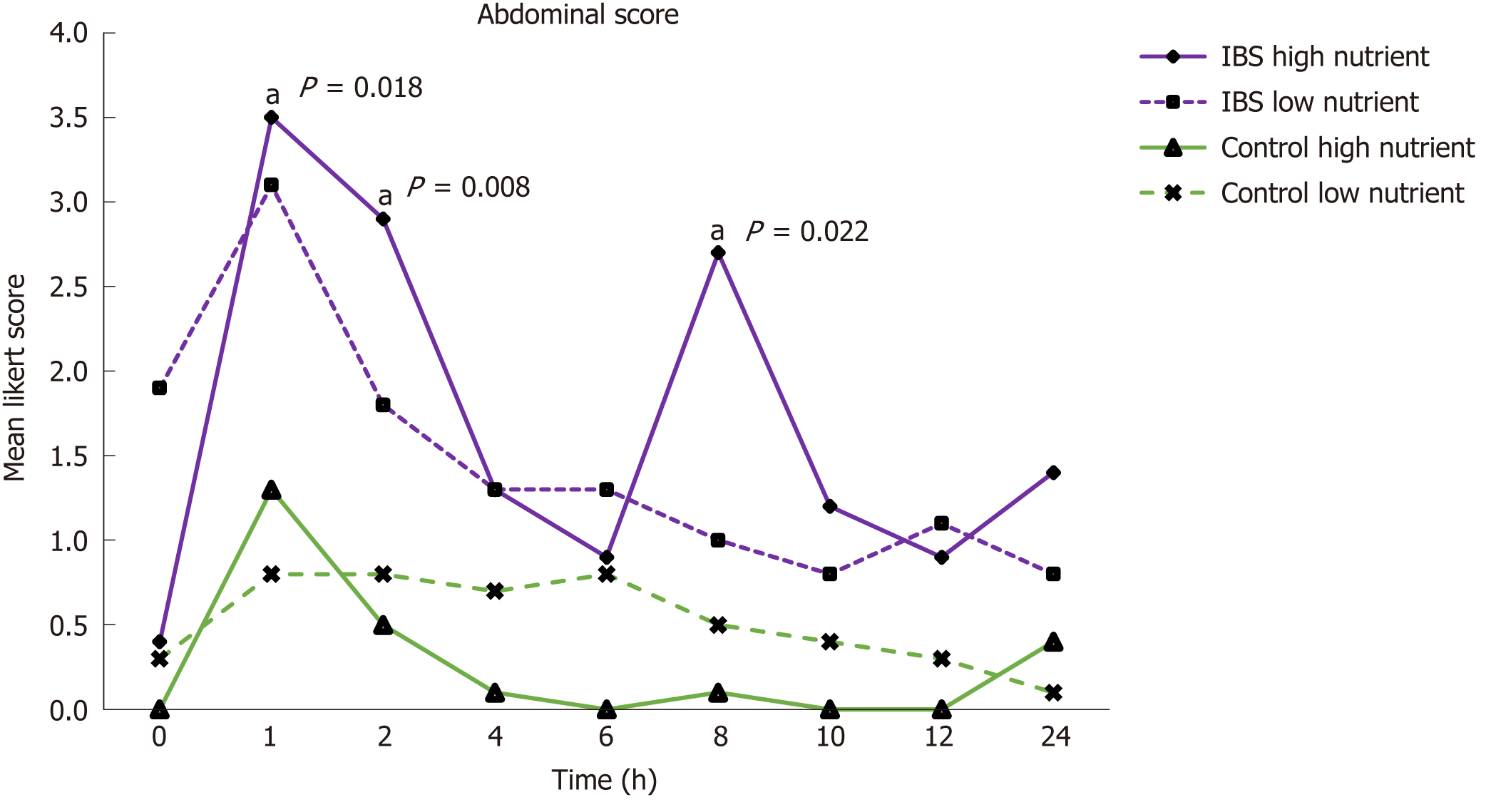

In the control group, the mean Global Dyspepsia Score (Figure 2) and the mean global abdominal score (Figure 3) did not differ significantly after the two drinks.

IBS patients reported significantly higher Global Dyspepsia Scores after both the HN and LN drinks compared to controls. In the patients, compared to the LN drink, the mean Global Dyspepsia Score after the HN drink was higher (up to P = 0.016) from 45 to 120 min after the drink (Figure 2). This was a general effect (Table 3), as nausea, regurgitation, and epigastric bloating were each significantly greater after the HN drink.

| HN drink-individual symptoms assessed for the global dyspepsia score | Time in min | ||||||||||

| Symptom | Group | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 120 |

| Satiety | IBS | 0.3 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| Controls | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 1.6 | |

| Nausea1 | IBS | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Epigastric distension1 | IBS | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.6 |

| Controls | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.6 | |

| Epigastric pain | IBS | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Heartburn | IBS | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Regurgitation1 | IBS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

In the patients, the mean Global Abdominal Score during 24 h after the drinks was not significantly different between the HN and LN drinks, the greatest difference being at 8 h (3.4 vs 0.9, P = 0.082) (Figure 3). Notably, neither of the drinks had any impact on bowel function or stool consistency.

The mean Global Dyspepsia Score after the HN drink was significantly higher in patients from 25 min till measurements ceased at 120 min (Figure 2). Table 3 gives the mean levels of the individual symptoms contributing to the Global Dyspepsia Score in IBS patients and controls after the HN drink. The mean Global Abdominal Score was also significantly higher after the HN drink (P = 0.008 at 2 h) in IBS patients than in the control subjects from 1 h to 10 h after the drink (Figure 3). Levels of the individual symptoms that contributed to the Global Abdominal Score are given in Table 4.

| HN drink-global symptoms | Time in h | |||||||||

| Symptom | Group | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 24 |

| Heartburn | IBS | 0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Regurgitation1 | IBS | 0.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Controls | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal distension1 | IBS | 0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Controls | 0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal pain | IBS | 0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Controls | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | |

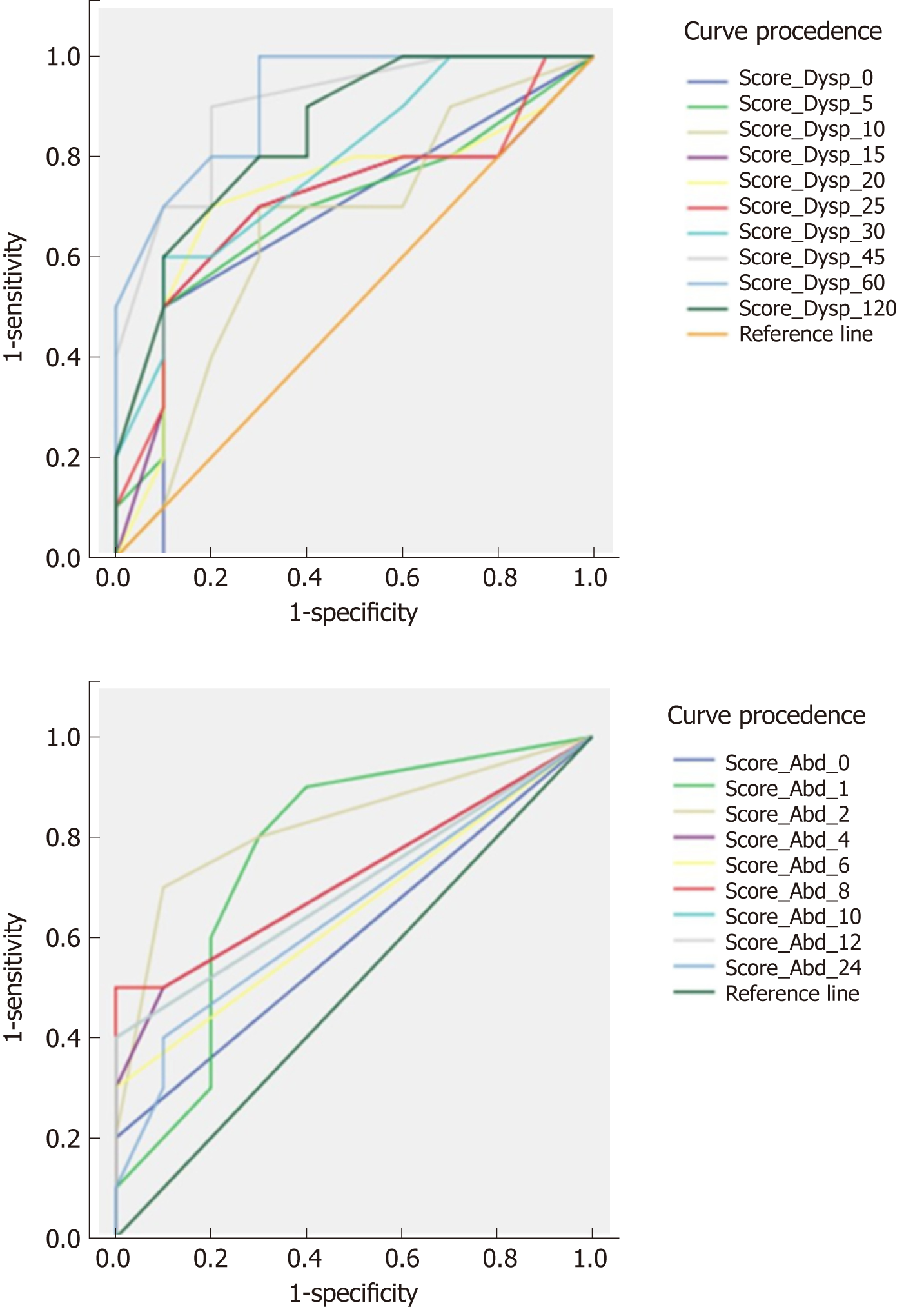

Figure 4 shows the ROC curves for the mean Global Dyspepsia Score in distinguishing IBS patients from healthy subjects. At 45 min after the HN drink, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.915. Sensitivity and specificity for recognition of IBS vary between 80%-90% and 70%-90% according to the cut-off values chosen. For the mean Global Abdominal Score, the AUC was lower at 0.825. Depending on the cut-off values chosen, sensitivity and specificity ranged from 80%-90% and 30%-40%. The ROC curve for the sum of the mean Global Dyspepsia and Abdominal Scores for the first 2 h of observation also had a lower predictive value (AUC 0.88) than the Global Dyspepsia Score.

We have found that the HN 500 kcal Ensure™ NDT triggered substantial GI symptoms in a cohort of IBS patients, an effect not seen in our healthy subjects. The dyspeptic symptoms during the first 2 h after the HN drink appear to have the greatest potential for making a positive diagnosis of IBS. Also, in patients, the HN drink induced more abdominal symptoms than the LN drink, an effect not seen in the controls.

A simple, non-invasive test for IBS is needed that can reassure patients and doctors of the accuracy of this diagnosis. Acceptance of the diagnosis of IBS is important for therapeutic success[6]. To our knowledge, this exploratory study is the first to test directly the use of a NDT for diagnosis of IBS. Our results are consistent with those of Haag et al[24] who included 18 IBS patients as a control group for the use of the NDT in diagnosis of FD, as they found that symptoms were provoked in IBS patients by a substantially larger 600 mL, 900 kcal liquid test meal. These symptoms were less severe than in the FD patients but more intense than in the healthy controls.

Since completion of our studies described here, Posserud et al[25] have reported on the generation of symptoms in IBS patients and healthy controls over 4 h after a solid test meal of 540 kcal[25]. Consistent with our data, the patients had more early satiety, nausea, and abdominal discomfort than the controls. The symptom burden in the first 2 h after the solid meal in IBS patients correlated with their basal IBS severity score and not with basal FD-related symptoms. We chose not to use a solid food caloric load because of the practical challenge of preparing a reliably standardized solid test meal. The meal used by Posserud et al[25] contained accurately defined weights of oat bran, applesauce, crispbread, margarine, and cheese and set volumes of milk and apple juice[25]. Such a meal is much less convenient than a standard liquid nutrient supplement and difficult to reproduce accurately from country to country.

Though NDTs have been widely used in FD studies, they have not been adequately standardized. Most NDTs use a nutrient mixture of between 1 kcal/mL and 1.5 kcal/mL, ingestion rates of 10 mL/min to 30 mL/min, and total volumes of 650 mL to 1000 mL[15,16]. Abnormal gastric volume accommodation and slow gastric emptying have been found in only a proportion of FD patients. The presence of these abnormalities has been only weakly correlated with a positive NDT[10,14,15,24]. Visceral hypersensitivity is considered to be the most plausible underlying mechanism for symptom generation, a feature shared with patients with both FD and IBS.

The exploratory nature of our study prompted us to use a small case-control study design, with intensive collection of symptom data in very well-defined and severely symptomatic IBS patients and in control subjects. These data give useful guidance for future studies focused on defining the most simple yet effective design for a NDT in suspected IBS.

We also addressed the unexplored possibility that the NDT could provoke diagnostically useful symptoms for up to 24 h in IBS patients. The 24 h symptom assessment did not add anything to the diagnostic yield of the Global Dyspepsia Score over the first 2 h after ND ingestion. Our data indicate that a diagnostic NDT could be restricted to recording of symptoms for only 2 h to 3 h after the test drink, a substantial simplification of the protocol we tested. We were surprised that dyspeptic symptoms during the first 2 h (satiety, epigastric bloating, epigastric pain, heartburn, and regurgitation) achieved the best yield for the recognition of IBS patients, but this finding is consistent with the data of Posserud et al[25].

Consistent with other tertiary center Spanish IBS cohorts, our IBS patients were markedly impacted by their symptoms and so an ideal population to evaluate in an exploratory study[26]. IBS involves biopsycho-social aspects that may vary between individuals that equally fulfil the Rome criteria[4]. This variation can hinder the reproducibility within a small cohort. Thus, future studies need to enroll a larger number of patients whose symptoms are less severe and thus more representative of the spectrum of patients presenting in primary and secondary care. The non-invasive and simple nature of the NDT means it would have a low cost, making it suitable for wide use. Adding relatively inexpensive, routine non-invasive screening for celiac disease, anemia, and thyroid dysfunction in patients suspected to have IBS could help to enhance the specificity of the NDT. Future studies need to address whether a NDT can distinguish IBS from other digestive disorders that can present with similar symptoms. The key question is whether a positive NDT arises only from visceral hypersensitivity, which does not underly symptom provocation in other diseases such as specific epithelial or gross anatomical abnormalities of the gut.

Although the physician-conducted patient screening methods were carefully designed to exclude patients with IBS and FD overlap, 4/10 fulfilled FD criteria in the Rome III questionnaire, which was self-completed by patients after study entry. Inclusion of some IBS patients with co-existing FD in our study probably does not detract from our major conclusions, given how common this coexistence is[27,28]. Posserud et al[25] did not exclude IBS patients who also met diagnostic criteria for FD in their solid meal study and found no differences in meal-associated symptom provocation between their FD-negative and positive IBS patients[25].

We conclude that use of a diagnostic NDT for IBS is a promising option. Questions that need to be addressed are how well a NDT would distinguish between IBS and other GI disorders across a spectrum of symptom severity, how to streamline symptom recording without loss of diagnostic performance, and what is the best amount of calories and possibly fermentable oligo-di-mono-saccharides and polyols in the test drink.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is highly prevalent worldwide. It is among the most common causes for gastroenterologist consultation and a significant economic burden in healthcare systems. The diagnosis of IBS is made when the symptom pattern fulfills Rome Criteria and underlying organic pathology is ruled out by tests that usually require invasive procedures, such as endoscopy or imaging examinations with radiation. Patients often conclude that their physician does not know what disease they are suffering from. Physicians are often tentative in their diagnosis of IBS and unsure how many investigations they should order to exclude other possible causes of their patient’s symptoms. The lack of a specific diagnostic test for IBS is an important gap in the physician’s toolkit. The symptom provocation caused by a nutrient drink test (NDT) has been used as a tool for the diagnosis of a very similar syndrome - functional dyspepsia (FD), whose symptoms usually overlap with IBS. In both IBS and FD, there is an abnormally heightened level of gut sensations, which is known as “visceral hypersensitivity”. The use of a NDT for diagnosis of IBS has not been previously evaluated.

This study focused on the design of a simple, inexpensive, and non-invasive diagnostic tool for IBS. The study tested whether prolongation of symptom recording beyond the 3 h-4 h of the provocative drink would improve diagnostic outcomes. The existence of a validated, simple test for IBS could reduce the use of invasive tests and exposure to X-rays in IBS patients.

The main objective was to determine whether the symptoms triggered by a highly caloric drink can differentiate IBS patients from healthy controls.

After ingestion of the high and low nutrient drinks, given on separate days, subjects were screened for gut symptoms face-to-face every 5 min for the first 2 h and by telephone until 24 h after drink ingestion.

This study has shown consistent provocation of symptoms during the first 2 h after a high nutrient drink in IBS patients, an effect not seen in the healthy subjects. Continuation of symptom monitoring up to 24 h after the drink did not enhance diagnostic outcomes.

Our data show that the NDT is a promising non-invasive test for IBS diagnosis and provide guidance for simplification of the test procedure.

More studies are needed since the patients enrolled in this project were especially severely affected and so not representative of the entire spectrum of IBS. The major priority for future research is a large-scale investigation of the diagnostic performance of the NDT in less severely symptomatic IBS patients, compared with patients with abdominal symptoms arising from structural (organic) disorders of the gut.

To Professor John Dent, for his detailed inputs to this paper and for English language styling and corrections. To Abbott Spain for their donation of Ensure HN samples for performing this study. To Dr. Monica Enguita for her input in formatting the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Abbasnezhad A, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Soares RLS S- Editor: Yan JP L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 108.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Ford AC, Talley NJ, Walker MM, Jones MP. Increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Case-control study of 23471 primary care patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Badia X, Mearin F, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M, Talley NJ. Burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome comparing Rome I and Rome II criteria. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20:749-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;pii:S0016-5085(16)00222-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 1882] [Article Influence: 209.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, Bolino C, Pintos-Sanchez MI, Moayyedi P. Validation of the Rome III criteria for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in secondary care. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1262-70.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quigley EM, Bytzer P, Jones R, Mearin F. Irritable bowel syndrome: The burden and unmet needs in Europe. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:717-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, Lacy BE, Olden KW, Crowell MD. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2454-2459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van der Veek PP, Van Rood YR, Masclee AA. Symptom severity but not psychopathology predicts visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Missanelli A, Mazzocchi S, Corazza GR. Meal induced rectosigmoid tone modification: A low caloric meal accurately separates functional and organic gastrointestinal disease patients. Gut. 2006;55:1409-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Passos MC, Serra J, Azpiroz F, Tremolaterra F, Malagelada JR. Impaired reflex control of intestinal gas transit in patients with abdominal bloating. Gut. 2005;54:344-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, Cuomo R, Janssens J. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52:1271-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lied GA, Lillestøl K, Lind R, Valeur J, Morken MH, Vaali K, Gregersen K, Florvaag E, Tangen T, Berstad A. Perceived food hypersensitivity: A review of 10 years of interdisciplinary research at a reference center. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1169-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Ostgaard H, Lomholt-Beck B, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Low densities of serotonin and peptide YY cells in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:873-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: A simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 1214] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Cuomo R, Sarnelli G, Grasso R, Bruzzese D, Pumpo R, Salomone M, Nicolai E, Tack J, Budillon G. Functional dyspepsia symptoms, gastric emptying and satiety provocative test: Analysis of relationships. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1030-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, Burton DD. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1029] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee S, Park M, Choi S, Nah Y, Abbey SE, Rodin G. Stress, coping, and depression in non-ulcer dyspepsia patients. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in RCA: 31705] [Article Influence: 754.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11319] [Cited by in RCA: 12753] [Article Influence: 439.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Santa María M, Jaramillo MA, Otero Regino W, Gómez Zuleta MA. Validación del cuestionario de reflujo gastroesofágico “GERDQ” en una población colombiana. Asoc Colomb Gastroenterol Endosc Dig Coloproctología y Hepatol. 2013;28:199-206. |

| 22. | Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, Tack J. Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI): Development and validation of a patient reported assessment of severity of gastroparesis symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:833-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1858] [Cited by in RCA: 2093] [Article Influence: 74.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Haag S, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Symptom patterns in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: Relationship to disturbances in gastric emptying and response to a nutrient challenge in consulters and non-consulters. Gut. 2004;53:1445-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Posserud I, Strid H, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Svensson U, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L, Simrén M. Symptom pattern following a meal challenge test in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and healthy controls. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:358-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Almansa C, Díaz-Rubio M, Rey E. The burden and management of patients with IBS: Results from a survey in spanish gastroenterologists. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:570-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jarbøl DE, Rasmussen S, Balasubramaniam K, Elnegaard S, Haastrup PF. Self-rated health and functional capacity in individuals reporting overlapping symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome - a population based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Halder SL, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: A 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |