Published online Oct 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6911

Peer-review started: June 10, 2017

First decision: July 13, 2017

Revised: July 26, 2017

Accepted: August 15, 2017

Article in press: August 15, 2017

Published online: October 7, 2017

Processing time: 112 Days and 2.5 Hours

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) are particularly rare. The various forms of PNETs, such as cystic degeneration, make differentiation from other similar pancreatic lesions difficult. We can detect small lesions by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and obtain preoperative pathological diagnosis by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). We describe, here, an interesting case of pNET in a 42-year-old woman with no family history. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed an 18 mm × 17 mm cystic lesion with a nodule in the pancreatic tail. Two microtumors about 7 mm in diameter in the pancreatic body detected only by EUS, cystic rim and nodules all showed similar enhancement on contrast-harmonic EUS. Preoperative EUS-FNA of the microtumor was performed, diagnosing multiple pNETs. Macroscopic examination of the resected pancreatic body and tail showed that the cystic lesion had morphologically changed to a 13-mm main nodule, and 11 new microtumors (diameter 1-3 mm). Microscopically, all microtumors represented pNETs. From the findings of a broken peripheral rim on the main lesion with fibrosis, rupture of the cystic pNET was suspected. Postoperatively, pituitary adenoma and parathyroid adenoma were detected. The final diagnosis was multiple grade 1 pNETs with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. To the best of our knowledge, no case of spontaneous rupture of a cystic pNET has previously been reported in the English literature. Therefore, this case of very rare pNET with various morphological changes is reported.

Core tip: Cystic or multiple pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) are very rare. This report describes a case of cystic pNET with multiple small tumors diagnosed from endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) alone. Preoperative diagnosis was able to be obtained by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Postoperatively, 11 other micro-pNETs with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 were detected and cystic pNET morphologically changed to a small nodule because of suspected spontaneous rupture. Spontaneous rupture of cystic pNET has not been reported previously in the English literature.

- Citation: Sagami R, Nishikiori H, Ikuyama S, Murakami K. Rupture of small cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with many microtumors. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(37): 6911-6919

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i37/6911.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6911

Neuroendocrine tumors can arise in endocrine organs throughout the whole body and cause various clinical symptoms. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) are particularly rare, representing only 1%-2% of all pancreatic neoplasms[1]. PNETs sometimes show various forms, such as cystic degeneration[2] or multiple microtumors[3], but such variations appear to be rare.

Most pNETs are solid and show strong enhancement during the arterial phases on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT)[4-6]. Diagnosis is therefore relatively easy. However, morphologically changed pNETs, such as cystic pNETs, are difficult to differentiate from other pancreatic cystic tumors[7]. Multiple PNETs are often diagnosed in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)[8], but diagnosis of microtumors in the pancreas on CT is difficult. In such cases, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is superior to CT for detecting pNETs, particularly small lesions[9]. Furthermore, contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) allows the diagnosis as pNETs with hypervascular enhanced tumors with high sensitivity and specificity, and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) enables preoperative pathological diagnosis[10].

This paper presents a case of pNETs with microtumors detected only by EUS in a 42-year-old woman with MEN1. In addition, a rare event of spontaneous rupture of the cystic pNET was strongly suspected from the postoperative pathological findings.

A 42-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of a pancreatic cystic lesion incidentally detected on unenhanced CT performed for inspection of painless enlargement of a cervical lymph node 1 mo earlier. No physical findings involving the abdomen were evident. No contributory family history was elicited. The patient had a history of urinary stones at 30-years-old. The only abnormality from laboratory tests was a mild elevation of liver enzymes.

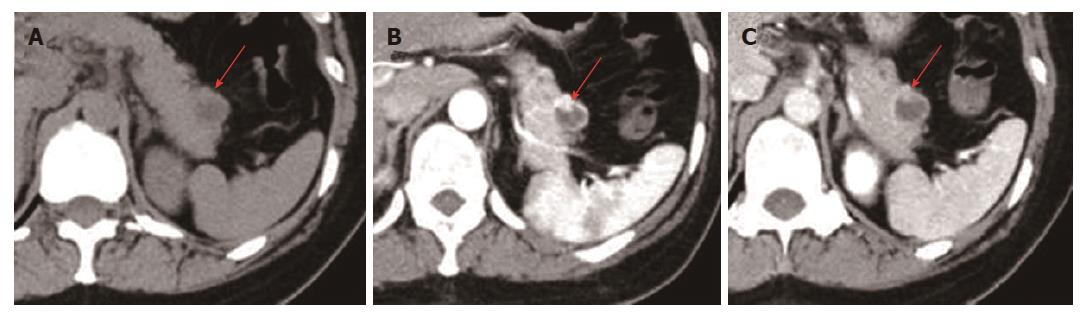

Unenhanced CT revealed a 16 mm × 15 mm, somewhat obscure cystic lesion in the pancreatic tail (Figure 1A). Contrast-enhanced CT revealed an 18 mm × 17 mm cystic lesion with a well-defined, hyperenhanced thin peripheral rim and a nodule about 6 mm in diameter inside the rim (Figure 1B). The outer rim was enhanced to a greater degree than normal pancreatic parenchyma during the arterial phases of bolus contrast administration, and iso-enhanced during the portal venous phase (Figure 1B and C).

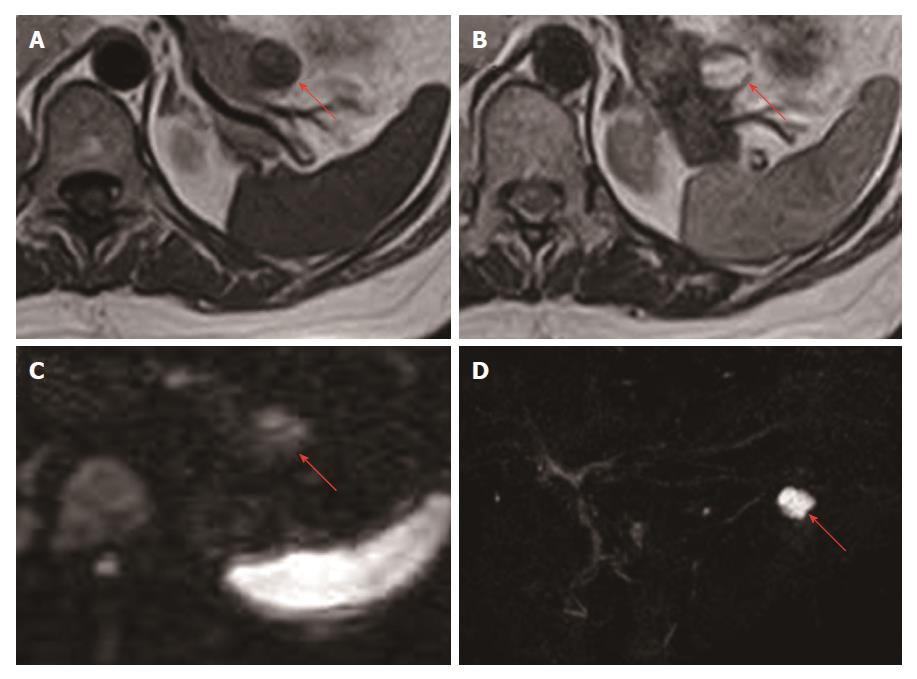

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion in the pancreatic tail appeared hypointense and some areas appeared relatively hyperintense compared to inside the cyst on T1-weighted images (Figure 2A), and mainly hyperintense with a hypointense peripheral rim and nodule on T2-weighted images (Figure 2B). On diffusion-weighted images, the lesion appeared relatively hyperintense (Figure 2C). The lesion was not continuous with the main pancreatic duct on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (Figure 2D).

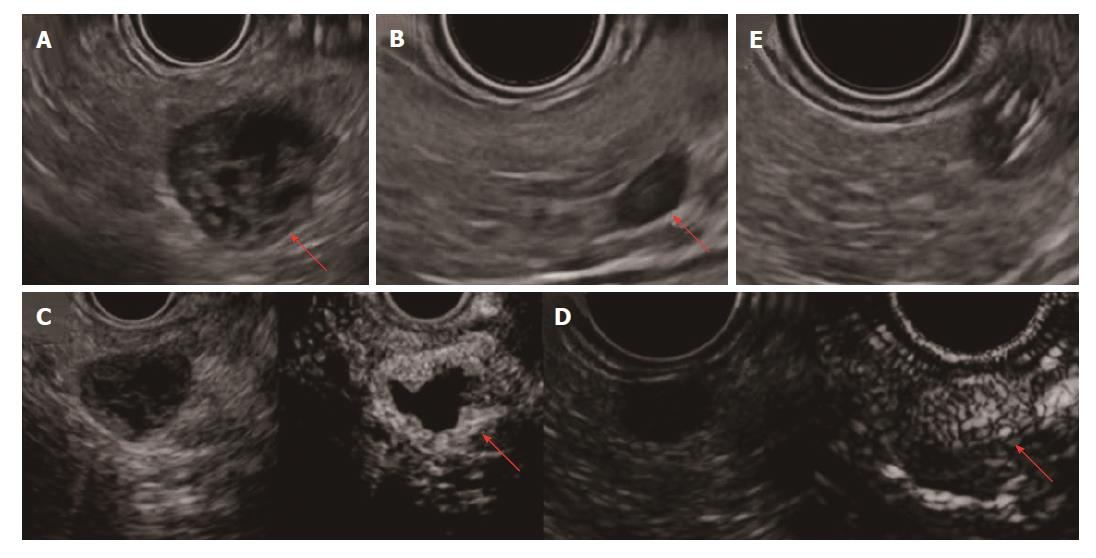

We also performed EUS, showing the cyst with a low echoic peripheral rim and nodule. Inside the cyst, no echoic fluid or solid structure was detected, and internal bleeding or necrosis was expected (Figure 3A). Apart from the main lesion, we detected two microtumors (7 mm and 6 mm in diameter) in the pancreatic body only on EUS (Figure 3B). On CH-EUS, the relatively thick rim of the cystic lesion, nodule and two microtumors showed similar enhancement from immediately after the injection of contrast medium (Figure 3C and D). We performed EUS-FNA of a 7-mm microtumor (Figure 3E).

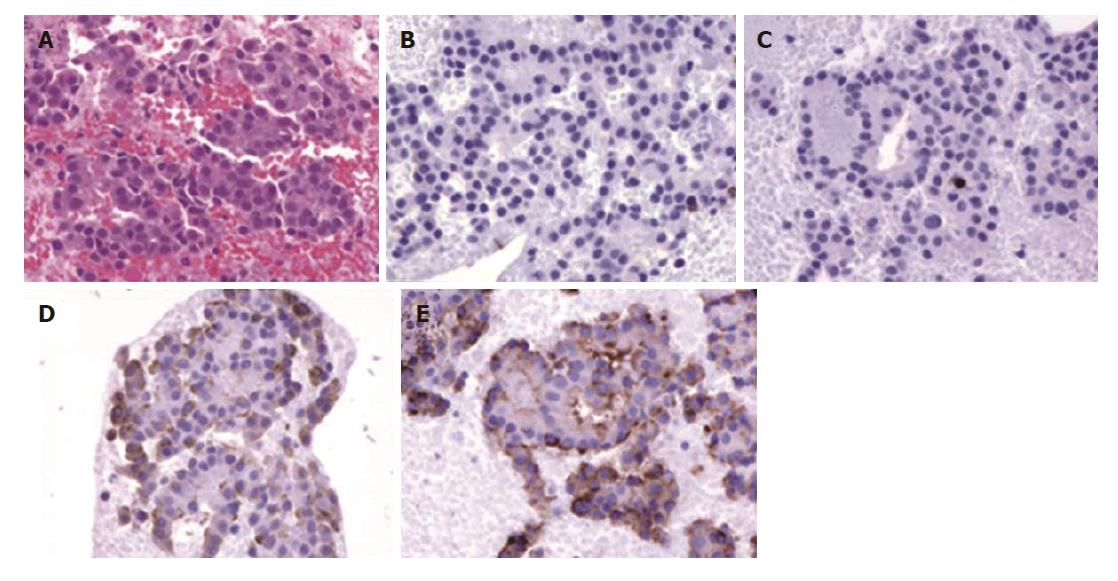

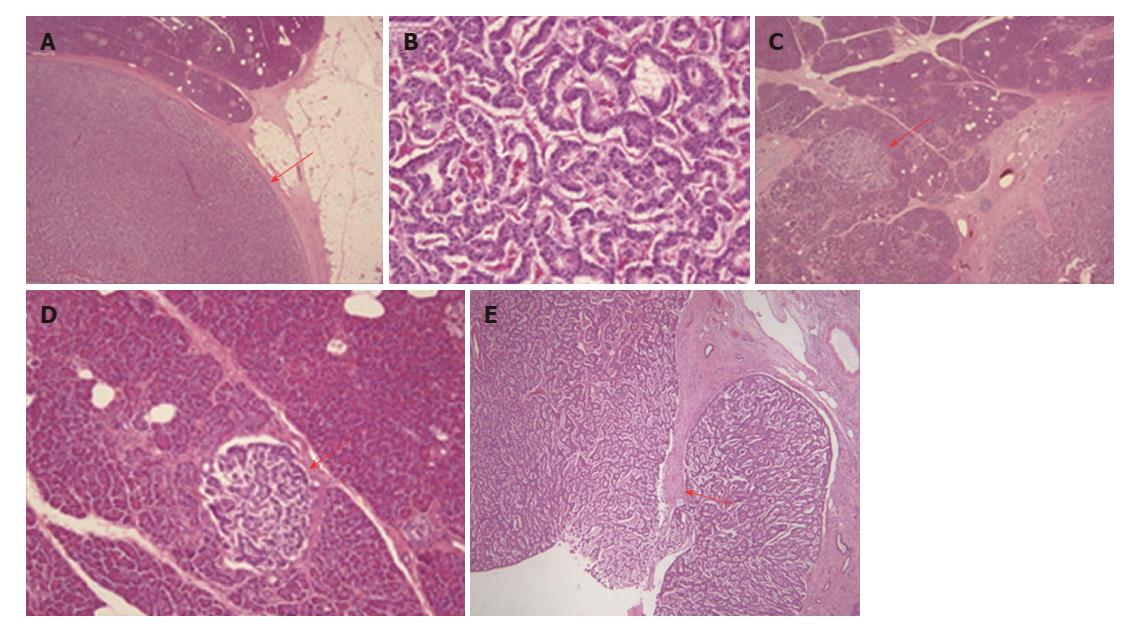

Histopathologically, the EUS-FNA specimen comprised cells with round nuclei (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100; Figure 4A). Tumor cells were negative for CD10 and CD56 (Figure 4B and C), but positive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4D and E) by immunohistochemical staining (×100). Based on these findings, multiple grade 1 endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas were diagnosed[11].

Preoperatively, endocrine examination was performed. Abnormal laboratory results included elevated parathyroid hormone at 136 pg/mL (normal, 15-65 pg/mL) and cortisol at 25.1 μg/dL (normal, 4.5-21.1 μg/dL), while other values were within normal ranges. The tumor was non-functional pNET, because levels of pancreatic endocrine hormones such as insulin were not elevated. After sufficient preparation and obtaining consent from the patient and her family members, we performed laparoscopic spleen-preserving pancreatic body and tail resection 50 d after EUS-FNA.

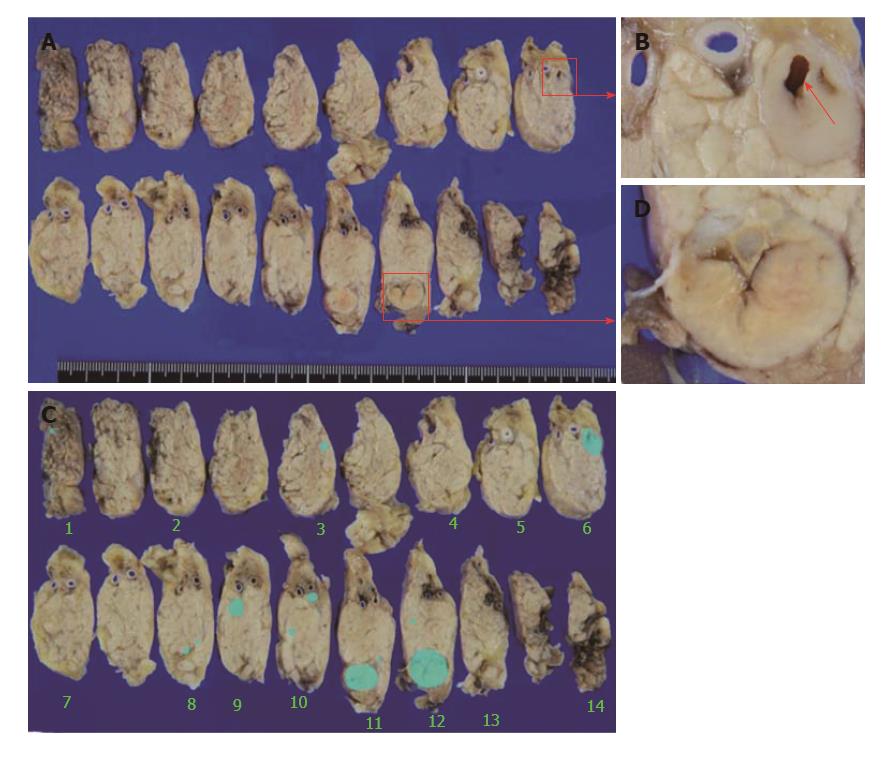

Macroscopically, the main cystic lesion morphologically changed to a nodule 13 mm in diameter with internal scarring (Figure 5A and C), considered to represent traces of cystic degeneration. The microtumor in the pancreatic body on which EUS-FNA was performed was separate from the main lesion (Figure 5A and B). A scar from EUS-FNA was identified in the microtumor (Figure 5B). Besides the main lesion and two microtumors detected previously on EUS, 11 microtumors (1-3 mm diameters) were newly detected (Figure 5D).

Microscopically, the main lesion comprised cells with round nuclei arranged in sheets or rosettes (Figure 6A), with < 2 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (Figure 6B). The Ki-67 index in the main lesion was 1.01%. All other microtumors showed similar findings (Figure 6C and D). After evaluating the potential causes of morphological changes to the main cystic lesion, the peripheral rim was considered most likely to have broken in one place, followed by fibrosis after inflammation (Figure 6E).

After surgery, whole-body examination detected asymptomatic pituitary adenoma and parathyroid adenoma on MRI and ultrasound. The final diagnosis was multiple pNET grade 1, stage 1 T1N0M0 with MEN1 and a strong suspicion of spontaneous rupture of the cystic pNET. As of the time of writing, the patient remains alive without recurrence for more than 2 years postoperatively. Asymptomatic pituitary adenoma and parathyroid adenoma are being followed-up by an endocrine physician, and no clinical symptoms or abnormal results from blood testing have been encountered.

PNETs are rare and represent only 1%-2% of all pancreatic neoplasms[1]. However, due to the development of increasingly sophisticated imaging modalities, more pNETs are being reported[12].

The clinical symptoms of pNET primarily depend on whether the tumor is functional or non-functional, and the type of hormone produced by a functional tumor[1]. Most pNETs are solid lesions, but some are detected as tumor with cystic degeneration[2]. Cystic pNETs were classically considered very rare, but recent studies have suggested that cystic pNETs may be more common than previously reported[13]. Some studies have reported that 9.3%-21% of pNETs are detected as cystic degeneration on imaging modalities including CT, ultrasound, MRI, and EUS or by pathological examination of a resected specimen[14-19].

Solid pNETs are typically enhanced to a greater degree than normal pancreatic parenchyma during the arterial and portal venous phases of bolus contrast administration[4-6], because of the rich vascularity[20]. On the other hand, the radiological features of cystic pNETs have been suggested to represent an enhanced outer rim with blood flow-rich tissue[21]. As another specific finding of pNETs, multiple and microtumors in the pancreas are rarely detected. Multiple PNETs are often diagnosed in cases of MEN1[8], but diagnosis of microtumors in the pancreas on contrast-enhanced CT is difficult[9].

EUS is superior to CT for detecting small pNETs. In a study of 231 pNETs, CT detected 84% of tumors but was more likely to miss lesions < 2 cm in diameter (P = 0.005), while the sensitivity of EUS for detecting 56 pNETs (91.7%) was greater than that of CT (63.3%; P = 0.0002), and EUS detected 20 of 22 CT-negative tumors (91%)[10]. Furthermore, CH-EUS allowed the diagnosis of hypervascularly enhanced tumors as pNETs with 78.9% sensitivity (95%CI: 61.4%-89.7%) and 98.7% specificity (95%CI: 96.7-98.8%) respectively[11].

In this manner, EUS appears useful for the diagnosis of pNETs, but we often encounter challenges, particularly in diagnosing cystic pNET. This is because we need to differentiate the pathology from other pancreatic cystic tumors, such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, mucinous cystic neoplasm, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, serous cystic neoplasm, solid and cystic papillary tumors, or even non-neoplastic pseudocyst[7].

In such cases, we should consider EUS-FNA for preoperative histological diagnosis. EUS-FNA correctly diagnosed PNETs, offering 90.1% diagnostic accuracy[22]. When CH-EUS was combined with EUS-FNA, the sensitivity of EUS-FNA increased from 92.2% to 100%[11]. EUS-FNA accuracies for the malignancy of cystic and solid PNETs were 89.3% and 90% respectively[23], but EUS-FNA for cystic lesions of the pancreas is not recommended in Japan.

In our case, the cystic lesion in the pancreas tail was initially detected on CT. MRI was additionally performed, but we could not obtain a confirmed diagnosis from the imaging findings. The cystic lesion was evaluated in more detail and 2 new microtumors were detected in the pancreatic body only on EUS. In addition, the rim of the cyst and microtumors were hyperenhanced on CH-EUS, and we became confident the lesions represented pNETs. In addition, we performed EUS-FNS of a microtumor, and obtained pathological confirmation of the preoperative diagnosis.

MEN is an autosomal-dominant inherited disease presenting with tumorous lesions, mainly in various endocrine organs[3], and 15% of MEN1 patients have no family history[24]. MEN1 is diagnosed when at least 2 of the main tumorous diseases (parathyroid tumor, pNET or pituitary tumor) are found, and hyperparathyroidism is the most frequent initial disease in MEN1 (85%)[25]. According to a Japanese nationwide survey, MEN1 was found in 10% of pNET patients. The type of pNET in MEN1 was gastrinoma in 25%, insulinoma in 14% and non-functioning in 6.1%[12]. In addition, PNETs in MEN1 often have multiple tumors in the pancreas, and 74% of pNET with MEN1 had multiple tumors[8].

This was a typical case of pNETs with MEN1, but spontaneous rupture of the cystic pNET was a remarkable feature. The rupture of a pancreatic neoplasm is very rare. Ruptures of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm[26-28], mucinous cystic neoplasm[29], acinar cell carcinoma[30,31] and anaplastic cell carcinoma[32] have been reported, but rupture of cystic pNET does not appear to have been described. Involvement of either infarction and liquefactive necrosis of a large tumor or internal hemorrhage have been considered as causes of cystic degeneration in pNETs[21,33]. The cause of cyst formation of cystic pancreatic NET, thus, remains controversial[15,34,35].

Spontaneous rupture of cystic lesions of the pancreas has been suggested due to high pressure inside the cyst or inflammatory stimulation by others factors, such as acute pancreatitis[27], but only a small number of cases have been reported, and the exact cause remains thusly unknown. In our case, internal bleeding, rather than necrosis, might have been involved in cystic degeneration. We performed EUS-FNA of the microtumor in the pancreatic body separate from the cystic pNET in the pancreatic tail, so EUS-FNA might not have been related to rupture.

We could not rule out the possibility that rupture was associated with instrumental pressure from EUS examinations, but such high pressure on the cystic lesion was considered unlikely to arise in normal EUS examination or EUS-FNA. The scar from EUS-FNA is shown in Figure 5B. The thin part of the rim was not intact, and thinning of the tumor part and high pressure inside the cyst were considered as causes, but more detailed causes of the rupture could not be clarified.

In conclusion, pNETs are rare and show various forms of tumor, such as cystic degeneration. PNETs with MEN1 often show multiple tumors, and detecting microtumors on CT or MRI is sometimes difficult so that EUS and CH-EUS should be performed. In addition, we should search for endocrine tumors in other organs affected by MEN1. To the best of our knowledge, spontaneous rupture has not been reported previously, so this case was reported.

We wish to thank endoscopic engineers Ohata T, Yamasaki K. Sakata N, Tauchi M, Tasaki M, Matou M and Kudou C of Oita San-ai Medical Center, for their helpful technical assistance in EUS.

A 42-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a pancreatic cystic lesion found incidentally on computed tomography (CT). She had no relevant family history.

Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET) with many microtumors.

Differential diagnoses included intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, mucinous cystic neoplasm, solid pseudopapillary tumor and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Abnormal laboratory results included mild liver enzyme, cortisol and intact parathyroid hormone elevation in blood serum

Contrast-enhanced CT showed an 18 mm × 17 mm cystic lesion with a well-defined hyperenhanced thin peripheral rim. On magnetic resonance imaging, the lesion appeared mainly hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. On EUS, apart from the main lesion, two microtumors were detected (7 mm and 6 mm) in the pancreatic body.

The final pathological diagnosis was multiple grade 1 pNETs. The main cystic lesion changed to a 13-mm nodule, and spontaneous rupture of the cystic pNET was strongly suspected.

The patient was treated with pancreatic body tail resection.

Recent studies suggest that cystic pNETs may be more common than previously reported, but rupture of a cystic pNET has not been reported.

There are no non-standard terms used in this manuscript.

The authors present this case to share important knowledge for pNET diagnosis.

The authors reported an interesting case, which they believed to be a spontaneous rupture of cystic pNET with many microtumors.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chowdhury P, Yasuda K, Yang F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Metz DC, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1469-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 542] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Colović R, Bilanović D, Milićević M, Barisić G. Cystadenomas of the pancreas. Acta Chir Iugosl. 1999;46:39-42. [PubMed] |

| 3. | WERMER P. Genetic aspects of adenomatosis of endocrine glands. Am J Med. 1954;16:363-371. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ichikawa T, Peterson MS, Federle MP, Baron RL, Haradome H, Kawamori Y, Nawano S, Araki T. Islet cell tumor of the pancreas: biphasic CT versus MR imaging in tumor detection. Radiology. 2000;216:163-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | King AD, Ko GT, Yeung VT, Chow CC, Griffith J, Cockram CS. Dual phase spiral CT in the detection of small insulinomas of the pancreas. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stafford-Johnson DB, Francis IR, Eckhauser FE, Knol JA, Chang AE. Dual-phase helical CT of nonfunctioning islet cell tumors. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:335-339. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mori E, Yuen K, Medrano H, Torres J, García C, Montes J. [Management of pancreatic cystic tumors in the Alberto Sabogal Sologuren hospital]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2012;32:169-177. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sakurai A, Suzuki S, Kosugi S, Okamoto T, Uchino S, Miya A, Imai T, Kaji H, Komoto I, Miura D. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 in Japan: establishment and analysis of a multicentre database. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khashab MA, Yong E, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Hruban RH, Olino K, Giday S, Fishman EK, Wolfgang CL. EUS is still superior to multidetector computerized tomography for detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:691-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kitano M, Kudo M, Yamao K, Takagi T, Sakamoto H, Komaki T, Kamata K, Imai H, Chiba Y, Okada M. Characterization of small solid tumors in the pancreas: the value of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:303-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, Caplin M, Couvelard A, de Herder WW, Erikssson B, Falchetti A, Falconi M, Komminoth P, Körner M, Lopes JM, McNicol AM, Nilsson O, Perren A, Scarpa A, Scoazec JY, Wiedenmann B; all other Frascati Consensus Conference participants; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS). TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1196] [Cited by in RCA: 1085] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ito T, Sasano H, Tanaka M, Osamura RY, Sasaki I, Kimura W, Takano K, Obara T, Ishibashi M, Nakao K. Epidemiological study of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:234-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel KK, Kim MK. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: endoscopic diagnosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:638-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ahrendt SA, Komorowski RA, Demeure MJ, Wilson SD, Pitt HA. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: is preoperative diagnosis possible? J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:66-74. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Goh BK, Ooi LL, Tan YM, Cheow PC, Chung YF, Chow PK, Wong WK. Clinico-pathological features of cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms and a comparison with their solid counterparts. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:553-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bordeianou L, Vagefi PA, Sahani D, Deshpande V, Rakhlin E, Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: a distinct tumor type? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1154-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baker MS, Knuth JL, DeWitt J, LeBlanc J, Cramer H, Howard TJ, Schmidt CM, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA. Pancreatic cystic neuroendocrine tumors: preoperative diagnosis with endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle immunocytology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:450-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Figueiredo FA, Giovannini M, Monges G, Bories E, Pesenti C, Caillol F, Delpero JR. EUS-FNA predicts 5-year survival in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kawamoto S, Johnson PT, Shi C, Singhi AD, Hruban RH, Wolfgang CL, Edil BH, Fishman EK. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with cystlike changes: evaluation with MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W283-W290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lewis RB, Lattin GE Jr, Paal E. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: radiologic-clinicopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30:1445-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ligneau B, Lombard-Bohas C, Partensky C, Valette PJ, Calender A, Dumortier J, Gouysse G, Boulez J, Napoleon B, Berger F. Cystic endocrine tumors of the pancreas: clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic features in 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:752-760. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Atiq M, Bhutani MS, Bektas M, Lee JE, Gong Y, Tamm EP, Shah CP, Ross WA, Yao J, Raju GS. EUS-FNA for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a tertiary cancer center experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:791-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ridtitid W, Halawi H, DeWitt JM, Sherman S, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, Coté GA, Al-Haddad MA. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: outcomes of preoperative endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration, and recurrence during long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2015;47:617-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Trump D, Farren B, Wooding C, Pang JT, Besser GM, Buchanan KD, Edwards CR, Heath DA, Jackson CE, Jansen S. Clinical studies of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). QJM. 1996;89:653-669. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Brandi ML, Gagel RF, Angeli A, Bilezikian JP, Beck-Peccoz P, Bordi C, Conte-Devolx B, Falchetti A, Gheri RG, Libroia A. Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of MEN type 1 and type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5658-5671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1115] [Cited by in RCA: 906] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rosenberger LH, Stein LH, Witkiewicz AK, Kennedy EP, Yeo CJ. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) with extra-pancreatic mucin: a case series and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:762-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee SE, Jang JY, Yang SH, Kim SW. Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma with atypical manifestations: report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1622-1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shimizu Y, Imaizumi H, Yamauchi H, Okuwaki K, Miyazawa S, Iwai T, Takezawa M, Kida M, Suzuki E, Saegusa M. Pancreatic Fistula Extending into the Thigh Caused by the Rupture of an Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Adenoma of the Pancreas. Intern Med. 2017;56:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bergenfeldt M, Poulsen IM, Hendel HW, Serizawa RR. Pancreatic ascites due to rupture of a mucinous cystic neoplasm. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:978-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mohammadi A, Porghasem J, Esmaeili A, Ghasemi-Rad M. Spontaneous rupture of a pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma presenting as an acute abdomen. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:293-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ando K, Ohkuni Y, Kaneko N, Narita M. Spontaneous rupture of the splenic metastasis in acinar cell carcinoma. Pancreas. 2009;38:836-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Narita M, Ikai I. Spontaneous Rupture of Anaplastic Pancreatic Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:664-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Takeshita K, Furui S, Makita K, Yamauchi T, Irie T, Tsuchiya K, Kusano S, Ohtomo K. Cystic islet cell tumors: radiologic findings in three cases. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:225-228. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Adsay NV. Cystic neoplasia of the pancreas: pathology and biology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:401-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Adsay NV, Klimstra DS. Cystic forms of typically solid pancreatic tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:81-88. [PubMed] |