Published online Aug 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5780

Peer-review started: April 9, 2017

First decision: April 26, 2017

Revised: May 7, 2017

Accepted: July 22, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: August 21, 2017

Processing time: 139 Days and 23.5 Hours

To investigate the changes of postoperative anal sphincter function and bowel frequency in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

A total of 127 patients with UC who underwent restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) during 20 years were retrospectively analyzed. The parameters of anal manometry and bowel frequency were compared according to the 6-mo intervals until 24 mo postoperatively. Manometry was used to measure the maximal squeezing pressure (MSP) and maximal resting pressure (MRP).

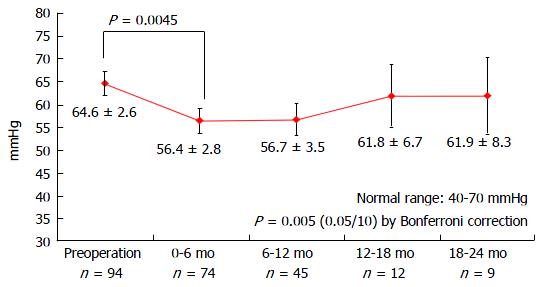

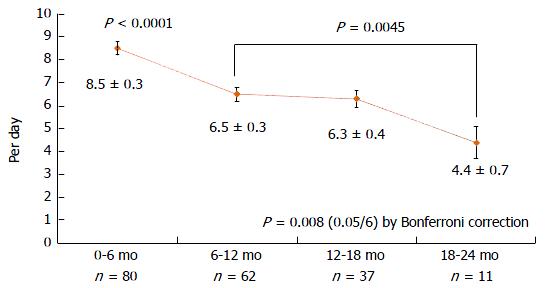

MSP decreased after surgery until 6 mo (157 to 142 mmHg); thereafter, it improved and was recovered to and maintained at the preoperative value at 12 mo postoperatively (142-170 mmHg, P < 0.001). Although the decreased MRP (65 to 56 mmHg) improved after 18 mo (62 mmHg), it did not completely recover to the preoperative value. The decreased rectal capacity after surgery (90 to 82 mL) gradually increased up to 150 mL at 24 mo. Although bowel frequency showed significant gradual decreases at each interval, it was stabilized after 12 mo postoperatively (6.5 times/d).

Postoperative changes of manometry and bowel frequency after restorative proctocolectomy in Korean patients with UC were not different from those in Western patients with UC.

Core tip: Although there has been an increase in the prevalence of ulcerative colitis (UC) and the numbers of UC surgery in Asian countries, studies on the functional outcomes of restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) or the quality of life in Asians are still deficient. Most UC studies on functional outcomes were done in Westerners. The authors found that maximal squeezing pressure, rectal capacity, and bowel frequency were stabilized at 12 mo after RPC. Although the decreased MRP was improved after 18 mo, it did not completely recover to the preoperative value. These findings in Korean patients with UC were not different from those in Western patients with UC.

- Citation: Oh SH, Yoon YS, Lee JL, Kim CW, Park IJ, Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim JC. Postoperative changes of manometry after restorative proctocolectomy in Korean ulcerative colitis patients. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(31): 5780-5786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i31/5780.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5780

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disorder that is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. The common surgical indications for UC are complications (such as severe UC) that are unresponsive to treatment, dysplasia or malignancy, bleeding, perforation, and a toxic megacolon. Restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) was first introduced in 1978 and is still used as the standard surgery[1]. However, RPC causes decreased rectal reservoir, loss of anorectal sensation, and anal sphincter injury from surgical manipulation, resulting in functional derangement of bowel movement in patients postoperatively[2-4]. The frequency of postoperative defecation ranges between 6 and 8 times/day, and more than one-third of patients experience anal incontinence[5].

The incidence and prevalence of UC in South Korea are still lower than those in Western countries but have been rapidly increasing during the last decades[6]. The mean annual incidence rate of UC in Koreans increased by 9-fold from 0.34 per 100000 in 1986-1990 to 3.08 per 100000 in 2001-2005[7]. This recent change in the incidence and prevalence of UC is attributable to environmental factors, such as Westernized lifestyles featuring antibiotic use and improved hygiene[7]. Moreover, differences between Asian and Western countries are also found in the family history and genetics of UC[6]. A family history of UC among Asian cohorts was previously noted to be uncommon, with a frequency ranging from 0.0% to 3.4%[8], considerably lower than the reported rates in Western series (range, 10%-25%)[9]. The genetic susceptibilities of Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) differ from those of whites, as they are not associated with NOD2/CARD15 mutations[10].

Although there has been an increase in the prevalence of UC and the numbers of UC surgery in Asian countries, studies on the functional outcomes of RPC or the quality of life in Asians are still deficient. Most UC studies on functional outcomes were done in Westerners. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the changes of postoperative anal sphincter function and bowel frequency in Korean patients with UC. Furthermore, we attempted to find the difference in functional outcomes between Western and Korean patients.

The clinical data of patients with UC who underwent laparotomy between October 1994 and June 2013 were collected retrospectively. During the study period, a total of 192 patients with clinically diagnosed UC underwent abdominal surgery. Of them, 41 patients who did not undergo RPC and 2 patients proven to have indeterminate colitis on pathology were excluded. One of the two patients with indeterminate colitis was included in the 41 patients who did not undergo RPC. Among 150 patients with RPC, 23 patients who did not undergo any preoperative or postoperative manometry were also excluded. Finally, 127 patients were analyzed. The clinical variables were sex, age at diagnosis, age at surgery, duration from diagnosis to surgery, indication for surgery, emergency operation, type of surgery, anastomotic configuration, presence of mucosectomy, and postoperative bowel frequency. Any complication that occurred within 90 d after RPC was defined as early complication. The mean follow-up duration was 71.5 mo (range, 3-192 mo). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center (registration No. 2017-0088).

Most of the RPCs were performed by experienced, IBD-specialized surgeons (Yu CS and Yoon YS) at our institution. The decision of performing surgery was made by gastroenterologists and IBD surgeons. The type of operation was decided by IBD surgeons, considering the severity of disease, patient’s condition, and presence of malignancy. IPAA included a 12-15-cm-long ileal J-pouch that was constructed by using linear staples and pouch-anal anastomosis through a double-stapling technique. If malignancy was suspected, cancer was present in the rectum, or removal of the remaining rectal mucosa was needed for any cause, mucosectomy was performed. Mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis were performed from the perineal side of patients. Then, diverting ileostomy was constructed in most cases. Usually, at least 2 mo later, the diverting ileostomy was closed after checking the anastomosis and the integrity of pouch through radiological evaluation with a water-soluble, double-contrast dye. Most RPCs were performed as two-stage procedures by using a double-stapling method.

Anorectal manometry was performed through water perfusion by using an eight-channel flexible catheter with side holes connected to a perfusion pump and a stationary manometry system (Polygraf ID; Medtronics, Copenhagen, Denmark). Anal manometry was performed with the continuous pull-through method (1 mm/s), starting 6 cm from the anal verge, by using a thin polyethylene (diameter: 5.5 mm, length: 150 cm). The catheter was constantly perfused with saline at a rate of 0.5 mL•channel-1•min-1, and was connected to a water-filled pressure transducer linked to multichannel recorder. A latex balloon at the tip of the perfused catheter (eight channels) was positioned in the ileal pouch or rectum so that the distal end of the balloon was 6 cm above the anal verge. Manometry was initially performed preoperatively. Secondary manometry was checked just before ileostomy closure. Thereafter, manometry was irregularly followed at 6-12-mo intervals without a protocol. The parameters of manometry, known to be indicators of anatomical and physiological changes, included the maximal squeezing pressure (MSP), maximal resting pressure (MRP), rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), and rectal capacity. The normal range is 100-180 mmHg for MSP, 40-70 mmHg for MRP, and 100-300 mL for rectal capacity. The presence of RAIR is the normal condition. Bowel frequency was retrospectively reviewed by using electronical medical records. Most patients were followed at 6-mo intervals until the postoperative first year; thereafter, they were followed at 1-year intervals. No questionnaires were used, and the degree of continence, night soiling, and whether gas could be discriminated from stool were not checked regularly. Therefore, only bowel frequency per day was evaluated during the postoperative period.

Because of our irregular check-up of manometry and records of bowel frequency, we arbitrary grouped the findings according to the 6-mo intervals until 24 mo after surgery. A linear mixed model was constructed to evaluate the differences between manometric measurements at 0-6, 6-12, 12-18, and 18-24 mo after and before the operation. The significance level for multiple comparisons was adjusted with Bonferroni’s method. The dependent variables at various times from before the operation to 24 mo after the operation were suspected to have a nonlinear relation with time. Thus, we fitted piecewise linear mixed models by assuming a series of linear segments and accompanying breakpoints. P-values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For piecewise linear mixed models, results are presented as β coefficients with SE. For linear mixed models, results are presented as least-square means with SE. SAS version 9.3 was used for statistical analyses.

Among 127 patients with RPC, 74 (58.3%) were men. The median ages at diagnosis and surgery of UC were 35.5 years (range, 14-65 years; SE, 12.4 years) and 39.6 years (range, 16-65 years; SE, 12.4 years), respectively. The mean interval from diagnosis to surgery was 50.3 mo (range, 0-279 mo; SE, 59.6 mo). Emergency operation was performed in four patients (3.1%). The most common indication for surgery was medical intractability, followed by malignancy (Table 1). A laparoscopic two-stage procedure of RPC with diverting ileostomy was performed in only one patient. The mean interval to ileostomy take down was 3.4 mo (range, 2.1-12 mo).

| Indication | n (%) |

| Medical intractability | 100 (78.7) |

| Malignancy | 10 (7.9) |

| Bleeding | 8 (6.3) |

| Perforation | 4 (3.1) |

| Toxic megacolon | 3 (2.4) |

| Fistula | 2 (1.6) |

| Total | 127 (100) |

Two-stage procedures of RPC with diverting ileostomy were performed in 109 patients (85.8%). Single procedures of RPC without diversion were done in 11 patients (8.7%). Three-stage procedures of total colectomy with end ileostomy, followed by completion proctectomy with IPAA construction and closure of ileostomy were performed in seven patients (5.5%). Double-stapling anastomoses were performed in 100 patients (78.7%), and hand-sewn anastomoses were done in 27 patients (21.3%). Complications occurred in 49 patients (39.2%). Anastomotic leakage was the most common early complication, and pouchitis was the most common late complication (Table 2).

| Variable | n (%) |

| Early complication | 19 (15.2) |

| Leakage | 5 (4.0) |

| Wound infection | 5 (4.0) |

| Bleeding | 2 (1.6) |

| Rectovaginal fistula | 2 (1.6) |

| Thrombosis | 2 (1.6) |

| Others | 3 (2.4) |

| Late complication | 30 (24.0) |

| Pouchitis | 17 (13.6) |

| Ileus | 5 (4.0) |

| Pouch failure | 3 (2.4) |

| Others | 5 (4.0) |

Preoperative manometries were possible in 94 of 127 patients, and follow-up manometries were performed in 74, 45, 12 and 9 patients at each 6-mo interval, consecutively. MSP immediately decreased after surgery until 6 mo but recovered at 12 mo postoperatively. A significant increase of MSP was found between 0-6 and 6-12 mo (142.4-169.7 mmHg, P = 0.0007; Figure 1). MRP significantly decreased after surgery from 64.6 to 56.4 mmHg (P = 0.0045). Despite a slight elevation (to 61.8 mmHg) after 12 mo, MRP was not recovered to the preoperative value. After 12 mo, MRP was maintained steadily (Figure 2). Rectal capacity slightly decreased at 6 mo (90.1 to 82.3 mL), but exceeded the initial volume up to 132.5 mL at 6-12 mo (P < 0.0001). Until 24 mo, rectal capacity gradually increased up to 150.3 mL (Figure 3). RAIR was identified in 20 patients (26.3%) and 5 patients (11.1%) at 0-6 and 6-12 mo, respectively.

Bowel frequency was studied in 80, 62, 37 and 11 patients at each 6-mo interval, consecutively. Although bowel frequency showed significant gradual decreases at each interval, it was stabilized after 6-12 mo postoperatively (Figure 4). The parameters of MSP, MRP, rectal capacity, and bowel frequency were compared between the double-stapling and hand-sewn anastomosis groups. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups.

RPC contributes to the enhancement of the quality of life of patients with UC by avoiding permanent ileostomy and maintaining intestinal continuity[11]. However, defecatory dysfunction after surgery exists in many forms, such as anal sphincter injury and sensory loss of the anal transition zone (ATZ) from mucosectomy, and has a relatively long recovery of 6-12 mo[12,13]. The external sphincter, which surrounds the internal sphincter and is innervated by somatic nerves, generates the voluntary anal squeeze and is also considered to be unaffected during mucosal proctectomy[14]. This implies that the operation disturbs the function of the internal sphincter but does not affect that of the external sphincter[15]. On the other hand, some studies insisted that weeks of non-use of the sphincter muscle might be the reason for the decrease in sphincter pressure. In fact, continuous mucous discharge from the pouch occurs during fecal diversion, implying that it is not in a totally resting state. After loop ileostomy closure, the external sphincter strength quickly improves owing to advanced exercise caused by loose stool. It thus compensates for the relatively low resting pressure values in these patients[16]. A previous study reported that MSP decreased from 87.1 mmHg preoperatively to 68.1 mmHg at 8 wk postoperatively; however, at 1 year, it increased to 72.3 mmHg[17]. Others showed no significant difference between preoperative values and those obtained 1 year after surgery when the mean and maximal squeezing pressures were compared[18]. In addition, another study reported that the MSP was 88.5 mmHg preoperatively and decreased by 12% to 68.0 mmHg before ileostomy closure. One year after ileostomy closure, the MSP was 96.5 mmHg, 8% higher than before surgery[16]. In this study, MSP decreased at 6 mo and stabilized after 12 mo (8-9 mo after ileostomy closure). The result of our study was not different from those of previous Western studies.

Around 60%-80% of MRP originates from the internal anal sphincter. This muscle, which is responsible for the maintenance of resting anal tone, is innervated by the autonomic nervous system and is under involuntary control[14]. It has also been observed that 84% of rectal mucosal tissue is composed of smooth muscle cell originating from internal sphincter muscle fiber, and the amount of smooth muscle has a significant relationship with the decrease of MRP that is associated with the bowel habit change of patients[19]. Injury to the internal sphincter muscle can directly result from operative trauma, or secondarily result from denervation or ischemia. Injury to the autonomic nerve of the internal sphincter muscle during rectal dissection results in decreased MRP[20]. Therefore, maintaining the integrity of the internal sphincter is responsible for preserving the MRP. The internal sphincter muscle is partially resected during mucosal proctectomy, and this loss of the muscle or the scar formation from the proctectomy contributes to the dysfunction of internal anal sphincter[21]. In previous studies, early postoperative anal manometry revealed a significantly lower MRP (42 ± 4 mmHg) than the preoperative value (65 ± 4 mmHg). During the follow-up, MRP increased but remained within the lower limits late postoperatively (49 ± 5 mmHg)[15]. Another study showed that preoperative MRP was 60.2 mmHg and the immediate postoperative MRP was 33.2 mmHg, a decrease of 45%. One year after ileostomy closure, the MRP was 46.2 mmHg, which was 23% lower than preoperatively[16]. In this study, MRP decreased until 6 mo postoperatively and then gradually increased, but recovered to some extent at 2 years postoperatively. That the internal anal sphincter is sensitive to even minor degrees of dilatation is evident from the decrease in MRP. Although there were reports of slight improvements in MRP with time after RPC, other studies did not find any improvement after 1 year[20]. In some studies, the postoperative change of MRP resulting from injury of the internal anal sphincter during IPAA may seem permanent[20]. Although it is difficult, avoiding injury to the internal anal sphincter during RPC is the key to preserving structural integrity, improving continence, and preventing the decrease of MRP[22].

Many studies reported that the use of stapler reduces the injury to internal sphincter and has a small effect of decreasing MRP, resulting in superior defecatory function[1,20,23,24]. In contrast, surgeons who advocate mucosal proctectomy emphasize that the complete removal of all rectal mucosa not only confers the highest likelihood of complete surgical cure but, more importantly, removes all future risk of malignant transformation[14]. However, a long-term follow-up study of dysplasia within the ATZ showed the incidence of dysplasia in the ATZ to be 4.5%, with significant correlation to prepouch risk factors, including colorectal cancer or dysplasia[23]. Other contrasting studies argued that the sphincter complex could be easily damaged and functionally compromised[25]. In addition, hand-sewn anastomosis was reported to entail prolonged operative time and frequent manipulation, resulting in decreased functional outcome and increased complications[20,23]. On the other hand, some studies suggest that there is no significant difference in complications and bowel frequencies between double-stapling and hand-sewn anastomosis, which was consistent with our study[14,23,26]. In this study, manometric findings and bowel frequencies were not different between the two anastomosis types.

RAIR is recognized as an important contributor to fecal continence through sampling and discrimination of contents. Preservation of the RAIR has been shown to correlate with a decreased incidence of nocturnal soiling after RPC[27]. RAIR decreases up to 75%-100% in the immediate postoperative period, but is known to recover over time[28]. A recent study claims that RAIR, which was identified in only 18% of patients after low anterior resection, was checked in 21% after 1 year and in 85% after 2 years, denoting that it has a significant meaning in the recovery of defecatory function[29]. In our study, recovery was seen in 20 patients (26.3%) and 5 patients (11.1%) after 6 and 12 postoperative months; however, additional information was not obtained owing to follow-up loss and inaccurate data.

Rectal capacity is known to be an important factor in stool frequency and improves with time for 1-2 years after surgery[12,13,30]. In addition, rectal capacity is a good index of the volume of the reservoir and can play an important role in the storing of stool[31]. This is increased compared with before surgery owing to the spontaneous adaptation of the ileal pouch and anal sphincter after ileostomy closure[31]. In some studies, the rectal capacity was 140-142 mL before ileostomy closure, 235-279 mL at 3-6 mo, and 338-344 mL at 12 mo[16]. In this study, rectal capacity also decreased in the immediate postoperative period, gradually increased after 6 mo, and showed marked improvement after 1 year, which seemed to contribute to the recovery of defecatory function.

The functional parameters of bowel frequency, which improved early after the operation, reached a plateau by 2 years and remained stable thereafter[32]. Defecatory function recovers over time after ileostomy take down and stabilizes to 6 to 7 per day at 1 postoperative year[32]. In a previous study, at 5 years after ileostomy closure, the average minimum and maximum 24-h frequency was 3.6 and 4.7, respectively[33]. In another study, a bowel frequency of 6 times/d was identified 3 years later[34]. In another report, the median bowel frequency per day was 6 at a mean follow-up of 40 mo[2]. A study of 100 J-pouch procedures reported that the bowel frequency at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 mo was 7.5, 6.5, 6.2, 5.4 and 5.4, respectively[35]. These results were similar to that of our study, which showed that the frequency decreased to 6.5 at 12 mo and 4.4 at 24 mo.

This study is limited by its retrospective design. Mainly, we did not use any questionnaire along with protocol. Major bias could result from the irregular check-up and follow-up of manometry. However, we attempted to minimize the bias of our study through specialized statistics. We expected to show the functional outcomes after RPC through our study. However, owing to the limited parameters, our study could show only a small part of the functional outcomes and quality of life after RPC.

In conclusion, the manometric findings of MSP and the rectal capacity and bowel frequency were stabilized at 12 mo after RPC. Although the decreased MRP was improved after 18 mo, it did not completely recover to the preoperative value. These findings in Korean patients with UC were not different from those of Western patients with UC.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disorder that is characterized by a relapsing and remitting course. The incidence and prevalence of UC in South Korea are still lower than those in Western countries but have been rapidly increasing during the last decades. Although there has been an increase in the prevalence of UC and the numbers of UC surgery in Asian countries, studies on the functional outcomes of restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) or the quality of life in Asians are still deficient. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the changes of postoperative anal sphincter function and bowel frequency in Korean patients with UC.

The manometric findings of maximal squeezing pressure (MSP), rectal capacity and bowel frequency were stabilized at 12 mo after RPC. Although the decreased maximal resting pressure (MRP) was improved after 18 mo, it did not completely recover to the preoperative value.

This study identified that the manometric findings and bowel frequency after RPC in Korean patients with UC were not different from those of Western patients with UC.

The presented research could be useful in studying the manometric functional outcomes and bowel frequency of UC patients in Asia and South Koera.

RPC: most RPCs were performed as two-stage procedures by using a double-stapling method. Ieal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA): included a 12-15-cm-long ileal J-pouch that was constructed by using linear staples and pouch-anal anastomosis through a double-stapling technique.

The authors retrospectively reviewed the data of patients who underwent RPC in a single institute and attempted to find the difference in functional outcomes between Western and Korean patients. This study could show only a small part of the functional outcomes and quality of life after RPC but the results were very interesting.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ladic A, Lakatos, PL, M'Koma AE S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1978;2:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in RCA: 913] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 947] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH. J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:800-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Park KJ, Park G. Analysis of the Results of Surgical Treatment Options for Ulcerative Colitis. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 1997;13:77-96. |

| 5. | Rink AD, Nagelschmidt M, Radinski I, Vestweber KH. Evaluation of vector manometry for characterization of functional outcome after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:807-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park SJ, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Clinical characteristics and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison of Eastern and Western perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11525-11537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee HS, Park SH, Yang SK, Lee J, Soh JS, Lee S, Bae JH, Lee HJ, Yang DH, Kim KJ. Long-term prognosis of ulcerative colitis and its temporal change between 1977 and 2013: a hospital-based cohort study from Korea. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:147-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang Y, Ouyang Q; APDW 2004 Chinese IBD working group. Ulcerative colitis in China: retrospective analysis of 3100 hospitalized patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1450-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Orholm M, Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Sørensen TI, Binder V. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ng SC, Tsoi KK, Kamm MA, Xia B, Wu J, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1164-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Silvestri MT, Hurst RD, Rubin MA, Michelassi F, Fichera A. Chronic inflammatory changes in the anal transition zone after stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: is mucosectomy a superior alternative? Surgery. 2008;144:533-537; discussion 537-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Goes R, Beart RW Jr. Physiology of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Current concepts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:996-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yu CS, Kim HC, Park SG, Kim SY, Cho YG, Hong HK, Kim JC. Manometric assessment after ileal pouch anal anastomosis. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2001;17:187-192. |

| 14. | Litzendorf ME, Stucchi AF, Wishnia S, Lightner A, Becker JM. Completion mucosectomy for retained rectal mucosa following restorative proctocolectomy with double-stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:562-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Braun J, Treutner KH, Harder M, Lerch MM, Töns C, Schumpelick V. Anal sphincter function after intersphincteric resection and stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:8-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luukkonen P. Manometric follow-up of anal sphincter function after an ileo-anal pouch procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Becker JM, Hillard AE, Mann FA, Kestenberg A, Nelson JA. Functional assessment after colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and endorectal ileoanal pull-through. World J Surg. 1985;9:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wexner SD, James K, Jagelman DG. The double-stapled ileal reservoir and ileoanal anastomosis. A prospective review of sphincter function and clinical outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Becker JM, LaMorte W, St Marie G, Ferzoco S. Extent of smooth muscle resection during mucosectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis affects anorectal physiology and functional outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:653-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tuckson W, Lavery I, Fazio V, Oakley J, Church J, Milsom J. Manometric and functional comparison of ileal pouch anal anastomosis with and without anal manipulation. Am J Surg. 1991;161:90-95; discussion 95-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sharp FR, Bell GA, Seal AM, Atkinson KG. Investigations of the anal sphincter before and after restorative proctocolectomy. Am J Surg. 1987;153:469-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kroesen AJ, Runkel N, Buhr HJ. Manometric analysis of anal sphincter damage after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:114-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lovegrove RE, Constantinides VA, Heriot AG, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Remzi FH, Nicholls RJ, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. A comparison of hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) following proctocolectomy: a meta-analysis of 4183 patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:18-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Williams NS, Marzouk DE, Hallan RI, Waldron DJ. Function after ileal pouch and stapled pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1168-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Holder-Murray J, Fichera A. Anal transition zone in the surgical management of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:769-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gozzetti G, Poggioli G, Marchetti F, Laureti S, Grazi GL, Mastrorilli M, Selleri S, Stocchi L, Di Simone M. Functional outcome in handsewn versus stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Surg. 1994;168:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saigusa N, Belin BM, Choi HJ, Gervaz P, Efron JE, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Recovery of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex after restorative proctocolectomy: does it correlate with nocturnal continence? Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Annibali R, Oresland T, Hultén L. Does the level of stapled ileoanal anastomosis influence physiologic and functional outcome? Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:321-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | O'Riordain MG, Molloy RG, Gillen P, Horgan A, Kirwan WO. Rectoanal inhibitory reflex following low stapled anterior resection of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:874-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oresland T, Fasth S, Nordgren S, Akervall S, Hultén L. Pouch size: the important functional determinant after restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chaussade S, Michopoulos S, Hautefeuille M, Valleur P, Hautefeuille P, Guerre J, Couturier D. Clinical and physiological study of anal sphincter and ileal J pouch before preileostomy closure and 6 and 12 months after closure of loop ileostomy. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pemberton JH, Kelly KA, Beart RW Jr, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Ilstrup DM. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Long-term results. Ann Surg. 1987;206:504-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Setti-Carraro P, Ritchie JK, Wilkinson KH, Nicholls RJ, Hawley PR. The first 10 years’ experience of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1070-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | McIntyre PB, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Beart RW, Dozois RR. Comparing functional results one year and ten years after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:303-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Becker JM, Raymond JL. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. A single surgeon’s experience with 100 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1986;204:375-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |