Published online Feb 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2236

Peer-review started: July 29, 2014

First decision: August 15, 2014

Revised: August 28, 2014

Accepted: October 15, 2014

Article in press: October 15, 2014

Published online: February 21, 2015

Processing time: 198 Days and 2.1 Hours

Although the development of de novo autoimmune liver disease after liver transplantation (LT) has been described in both children and adults, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)-primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) overlap syndrome has rarely been seen in liver transplant recipients. Here, we report a 50-year-old man who underwent LT for decompensated liver disease secondary to alcoholic steatohepatitis. His liver function tests became markedly abnormal 8 years after LT. Standard autoimmune serological tests were positive for anti-nuclear and anti-mitochondrial antibodies, and a marked biochemical response was observed to a regimen consisting of prednisone and ursodeoxycholic acid added to maintain immunosuppressant tacrolimus. Liver biopsy showed moderate bile duct lesions and periportal lymphocytes infiltrating along with light fibrosis, which confirmed the diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. We believe that this may be a case of post-LT de novo AIH-PBC overlap syndrome; a novel type of autoimmune overlap syndrome.

Core tip: We report a 50-year-old man who was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)-primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) overlap syndrome 8 years after liver transplantation. His liver function tests became markedly abnormal. Standard autoimmune serological tests were positive for anti-nuclear and anti-mitochondrial antibodies, and a dramatic biochemical response was observed to a regimen consisting of prednisone and ursodeoxycholic acid added to tacrolimus immunosuppression. Liver transplant biopsy showed moderate bile duct lesions and periportal lymphocytes infiltrating along with light fibrosis, which confirmed a diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome.

- Citation: Kang YZ, Sun XY, Liu YH, Shen ZY. Autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis concurrent with biliary stricture after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(7): 2236-2241

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i7/2236.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2236

Although the development of de novo autoimmune liver disease after liver transplantation (LT) has been described in both children and adults, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)-primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) overlap syndrome has rarely been found in liver transplant recipients. Here, we report a 50-year-old man who underwent LT for decompensated liver disease secondary to alcoholic steatohepatitis and developed AIH-PBC overlap syndrome 8 years later. The clinical information, diagnosis and treatment are described.

Previous medical history: A 50-year-old man was admitted to our hospital on May 14, 2013 with severe jaundice after liver transplantation eight years previously. He underwent deceased-donor liver transplantation (DDLT) and hepatic artery revascularization for alcoholic liver cirrhosis in April 2005 in another hospital. Three days post-operation, a stent was placed at the bypass site for thrombogenesis. Immunosuppressive therapy included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and glucocorticosteroids. Regular checks were arranged when out of hospital, and liver and kidney function and other results were satisfactory until abdominal ultrasound found obstruction at the site of the stent at the fifth year after surgery. However, nothing was done because collateral circulation had already formed. Five months before this admission, he saw doctors at the local hospital due to progressive jaundice and received magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Two stents were implanted for bile drainage because MRCP showed stricture at the transitional region of the common hepatic duct and common bile duct, although there was no significant improvement. Two weeks before this admission, his condition deteriorated, and the results of liver function tests were as follows: alanine transaminase (ALT) 295 U/L [normal range (NR): 5-40 U/L], aspartate transaminase (AST) 191 U/L (NR, 0-37 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 158 U/L (NR, 40-150 U/L), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 131 U/L (NR, 8-61 U/L), and total bilirubin (T-bil) 376.4 μmol/L (NR, 0-17.1 μmol/L). Stents were replaced by metallic ones and no improvement was achieved. For further treatment, he came to our hospital.

Physical examination (May 14, 2013): On physical examination, he was slim and weighed 58 kg, with stable vital signs. An old surgical scar was visible on the upper abdomen. Examination was only positive for deep jaundice and scratch marks all over the body; the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory and ultrasound examinations (May 15, 2013): The results of liver function tests, blood coagulation and antibody levels are shown in Table 1. The patient was investigated for virus infection, including cytomegalovirus, hepatitis virus A-E and Epstein-Barr virus, and no evidence was found. Immunological profile was positive for anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA), with titers of 1:320 and 1:100, respectively. Other autoantibodies were negative: anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, anti-soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas antigen antibody, and anti-liver cytosol antibody. Abdominal ultrasound showed chronic hepatic parenchymal lesions on the liver graft; small intrahepatic cysts; no abnormalities in large blood vessels and blood flow in the graft; and dilatation of the main bile tract.

| Items | Values | Normal range | Abnormal | |

| Liver function | LLN | ULN | ||

| T-bil (μmol/L) | 555.06 | 0 | 17.1 | ↑ |

| D-bil (μmol/L) | 243.59 | 0 | 6.8 | ↑ |

| ALB (g/L) | 31.6 | 34 | 48 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 196.3 | 5 | 40 | ↑ |

| AST (U/L) | 121.2 | 0 | 37 | ↑ |

| ALP (U/L) | 148 | 40 | 150 | |

| GGT (U/L) | 92.1 | 8 | 61 | ↑ |

| Blood coagulation | ||||

| PT (s) | 15.4 | 8.8 | 13.8 | ↑ |

| INR | 1.39 | 0.8 | 1.2 | ↑ |

| PTA | 55% | 80% | 120% | ↓ |

| APTT (s) | 42.2 | 26 | 42 | ↑ |

| TT (s) | 19.4 | 10 | 18 | ↑ |

| FIB (g/L) | 1.88 | 2 | 4 | ↓ |

| Immunological indexes | ||||

| IgG (mg/dL) | 2210 | 751 | 1560 | ↑ |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 230 | 82 | 453 | |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 56.3 | 46 | 304 | |

| C3 (mg/dL) | 382.6 | 79 | 152 | ↑ |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 416.5 | 16 | 38 | ↑ |

Given the patient’s history of biliary stricture at the transitional region of the common hepatic duct and common bile duct, we arranged for cholangiography on the day of admission and found that the stents had shifted. This was rectified by placing a biliary supporting tube instead, which was removed 3 d later because we deemed that the mild stenosis seen by cholangiography was not sufficient to account for such poor liver function. Therefore, immunological profile and antibody levels were examined on the following day (Table 1).

According to the elevated level of serum ALT (196.3 U/L) and IgG (2210 mg/dL), and taking ANA (1:320) into account, we suspected a diagnosis of AIH. Given that the serum AMA titer of this patient was 1:100, and AMA positivity indicates PBC[1-3], the diagnosis of PBC could not be excluded easily, despite the serum levels of ALP and GGT being lower than those in the guidelines. Liver biopsy was supposed to establish AIH-PBC, while it was not suitable for this patient at that particular time because of poor liver function and blood clotting.

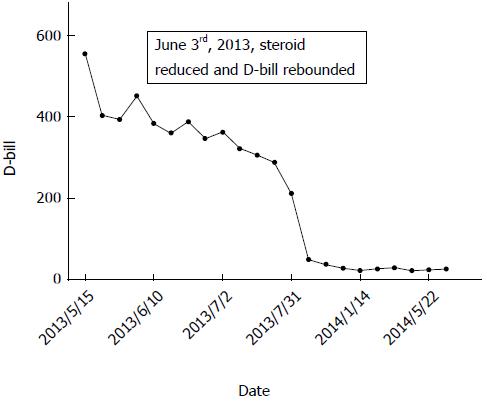

Methylprednisolone (40 mg, intravenously) was administered as soon as we suspected autoimmune liver disease (AILD), along with liver-protective agents and cholagogues, including reduced glutathione, S-adenosyl methionine and magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate. Liver function improved 1 wk later (May 22, 2013) and there were marked decreases in ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, T-bil and direct bilirubin. Such results gave us confidence to continue therapy until 10 d later (May 31, 2013) when severe hand cramp occurred as a side effect of methylprednisolone. Consequently, we reduced the dose of steroid to half to relieve cramp. By June 2, 2013, laboratory parameters rebounded to higher levels than before (Figure 1), which finally compelled us to make the following adjustments: (1) increase methylprednisolone dose back to 40 mg; (2) add vitamin D3 and calcitriol to treat side effects of steroids; and (3) replace reduced glutathione and magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) according to standard treatment.

From then on, laboratory parameters declined gradually (Table 2), except GGT, which had begun to increase in the previous month before his discharge from hospital (July 2, 2013) and sustained for nearly a year which provided us proofs of PBC when combined with positive AMA. Along with the recovery of liver function and coagulation, liver biopsy was performed on June 7, 2013, and showed the following: a total of six portal areas, whether integrated or not, and four central veins; swollen hepatocytes and scattered areas of fatty degeneration; obvious cholestatic hepatocytes and bile plugs in the bile canaliculus; focal necrosis of liver cells, and proliferation of small bile ducts in the portal areas; vacuolated biliary epithelia; and infiltration of inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, along with mild fibrosis. Such results supported our diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome.

| Date | ALB | ALT | AST | ALP | γ-GT | T-bil | D-bil |

| (g/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (μmol/L) | (μmol/L) | |

| 5/15/2013 | 36.1 | 196.3 | 121.2 | 148.0 | 92.1 | 555.06 | 243.59 |

| 5/22/2013 | 29.3 | 78.1 | 40.0 | 120.5 | 80.8 | 402.38 | 168.63 |

| 5/29/2013 | 30.3 | 78.9 | 38.0 | 126.6 | 113.7 | 394.12 | 189.85 |

| 6/3/2013 | 26.2 | 88.4 | 42.5 | 133.3 | 115.9 | 452.07 | 215.32 |

| 6/10/2013 | 29.3 | 90.6 | 40.1 | 130.4 | 126.7 | 383.22 | 189.22 |

| 6/18/2013 | 28.2 | 72.8 | 26.6 | 136.8 | 107.3 | 360.28 | 183.48 |

| 6/25/2013 | 24.9 | 112.8 | 29.3 | 139.0 | 88.6 | 387.34 | 184.84 |

| 6/28/2013 | 29.1 | 76.8 | 41.2 | 116.8 | 98.1 | 346.45 | 156.12 |

| 7/2/2013 | 34.4 | 103.5 | 67.0 | 126.3 | 124.3 | 363.45 | 169.51 |

| 7/9/2013 | 32.0 | 88.3 | 58.6 | 133.1 | 166.4 | 322.43 | 145.78 |

| 7/17/2013 | 32.9 | 94.3 | 56.5 | 134.5 | 233.8 | 306.58 | 176.52 |

| 7/24/2013 | 32.3 | 91.5 | 56.8 | 153.9 | 275.8 | 289.44 | 139.57 |

| 7/31/2013 | 30.8 | 69.9 | 40.5 | 131.1 | 240.8 | 212.71 | 103.69 |

Considering that the patient was undergoing recovery and was not receiving any special treatment, he was discharged on August 2, 2013. Dose of methylprednisolone was reduced to 30 mg intravenously (July 10, 2013) as the patient’s situation improved, and then to 20 mg intravenously 2 wk later (July 23, 2013) and 20 mg/wk orally prior to discharge. No changes were made to the other agents.

During follow-up, liver function tests were performed every month and the results were presented to us to determine whether drug adjustment was needed. According to laboratory parameters, we recommended to reduce 4 mg methylprednisolone at intervals of every other month until by 4 mg as maintenance therapy, and UDCA from three times to twice daily. No changes were made to vitamin D3 and calcitriol. Liver function was satisfactory during the past 6 mo, and GGT level had been falling. Laboratory parameters during follow-up are shown in Table 3.

| Date | ALB | ALT | AST | ALP | γ-GT | T-bil | D-bil |

| (g/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (U/L) | (μmol/L) | (μmol/L) | |

| 10/9/2013 | 32.2 | 79.3 | 43.8 | 135.5 | 478 | 50.1 | 23.45 |

| 11/14/2013 | 40.4 | 87 | 38 | 147 | 537 | 38.2 | 24.3 |

| 12/19/2013 | 40.3 | 82 | 41 | 142 | 481 | 29.2 | 14.7 |

| 1/14/2014 | 41.3 | 117 | 66 | 179 | 501 | 24.2 | 12.6 |

| 2/20/2014 | 39.9 | 92 | 49 | 153 | 422 | 27.2 | 12.5 |

| 3/20/2014 | 42.6 | 81 | 48 | 148 | 378 | 30.0 | 12.4 |

| 4/22/2014 | 43.3 | 71 | 37 | 163 | 373 | 23.1 | 8.5 |

| 5/22/2014 | 43.3 | 72 | 36 | 131 | 352 | 25.6 | 10.3 |

| 6/26/2014 | 42.7 | 72 | 40 | 154 | 313 | 27.3 | 10.3 |

AILDs are leading causes of liver cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease, which eventually require LT for patient survival. AIH-PBC overlap syndrome has been reported rarely in patients after LT. However, in 2005, Keaveny et al[4] reported a case of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome in which the standard autoimmune serological tests were negative and haplotype DR4 was associated with its development. The present patient was a 50-year-old man who had a history of excess alcohol consumption for up to at least 25 years and underwent DDLT for alcohol-related cirrhosis. It was a pity that immunological profile and antibody levels were not examined when ALT and AST were at their peak values before his admission to our center, which made us expose in such an embarrassing situation to determine the diagnosis of AIH due to slightly lesser serum ALT and IgG compared with criteria proposed by Chazouillères et al[5]. In addition, liver biopsy was not performed at that time because of the advance stage of the disease, which caused further confusion whether PBC was concurrent with AIH, because of AMA positivity and almost normal serum ALP and GGT. Fortunately, the diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was indicated by the decrease in laboratory parameters brought about by 1 wk empirical treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone. Final diagnosis relied on liver biopsy, which indicated moderate bile duct lesions and infiltration of periportal lymphocytes, along with mild fibrosis. Thus, diagnosis of AIH was based on elevated ALT (295 U/L) and liver biopsy, in association with increased serum IgG level and ANA positivity. The diagnosis of PBC was dependent on AMA positivity and moderate bile duct lesions, and further demonstrated by marked elevation of serum GGT levels during follow-up.

The term overlap syndrome was first used in the 1970s to describe variant forms of AIH that presented with characteristics of AIH and PBC or PSC[6-8], although there was no common definition or uniformly accepted diagnostic criteria at that time[9,10]. AILDs are a group of immunologically induced diseases that are either hepatocellular or cholestatic[11,12]. The hepatocellular forms are characterized by significant elevation of serum ALT and AST, together with elevated serum bilirubin. AIH is the typical example of hepatocellular AILD. The cholestatic forms involve the intra- and/or extrahepatic biliary systems. PBC is the second most common AILD, and develops with a cholestatic presentation and is characterized by AMA positivity. Another cholestatic form of AILD is PSC, in which chronic inflammation of the biliary tree leads to the development of strictures and biliary cirrhosis, with patients often suffering from recurrent cholangitis and ultimately needing LT[13].

Previously, there was no well-defined treatment for overlap syndrome, and as the diagnosis was often delayed, initial treatment of AIH-PBC was dependent on the initial presentation, clinical suspicion, and the clinician’s discretion[14]. Most patients with AIH achieved remission with therapy with corticosteroids and azathioprine; in some studies, 65% and 80% at 18 mo and 3 years, respectively[15-17]. The treatment of choice for patients with PBC was UDCA[18], which had been shown to improve clinical and biochemical indices by means of regulating the endogenous secretion of bile acid, reducing the cytotoxicity of endogenous bile acids, modulating the production of inflammatory cytokines, and being protective against oxidative stress and inhibiting apoptosis[19,20]. Recent reports have described another important role of UDCA as a key modulator of the cell cycle[21]. For patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, the combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine with UDCA is the best choice and recommended by many guidelines. In a retrospective study of a large cohort of patients with AIH-PBC[22], UDCA alone did not produce a biochemical response in most patients with severe interface hepatitis (without LT), and additional immunosuppressive therapy was needed. For transplant recipients, whether azathioprine is necessary because of administration of other immunosuppressants remains a problem that needs to be investigated in large studies.

In conclusion, we believed that our patient may be a case of post-LT de novo AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. This is a novel type of autoimmune overlap syndrome, and clinicians should note the occurrence of this type of AILD when managing liver transplant recipients and make correct decisions regarding the diagnosis and treatment.

We thank the staff at the Organ Transplantation Department, Tianjin First Central Hospital, Tianjin, for patient management.

The authors report a 50-year-old man who was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)-primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) overlap syndrome 8 years after liver transplantation (LT).

The diagnosis of AIH was on the basis of elevated alanine transaminase (ALT, 295 U/L) and liver biopsy results with assistance of increased serum IgG level and positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), and diagnosis of PBC was dependent on positive antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) and moderate bile duct lesions, further demonstrated by dramatic elevation of serum γ-glutamyl transferase levels during follow-up.

Authors excluded the previous diagnosis of biliary complications according to the mild stenosis presented on cholangiography.

Liver function tests showed serum ALT and IgG were 196.3 U/L and 2210 mg/dL, respectively. Standard autoimmune serological tests were positive for ANA (1:320) and AMA (1:100).

They excluded the previous diagnosis of biliary complications according to mild stenosis presented on cholangiography.

Liver biopsy indicated moderate bile duct lesions and periportal lymphocytes infiltrating along with light fibrosis.

Authors treated the patient with a combination of corticosteroids with ursodeoxycholic acid, with vitamin D3 and calcitriol to prevent side effects of steroids.

Keaveny et al reported AIH-PBC overlap syndrome in 2005, although standard autoimmune serological tests were negative, and only haplotype DR4 that is associated with the development of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was found.

The term overlap syndrome was first used in the 1970s to describe variant forms of AIH that presented with characteristics of AIH and PBC or primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Authors usually deemed that AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was an indication for LT, and this case reminds us that it could happen post-LT as well. Clinicians should note the occurrence of this type of liver disease when managing liver recipients and make correct decisions on the diagnosis and treatment.

The authors reported an interesting case of AIH/PBC that developed after LT, however, there were many mistakes that needed to be corrected.

P- Reviewer: Efe C, Urganci N S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1382] [Cited by in RCA: 1199] [Article Influence: 74.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Woodward J, Neuberger J. Autoimmune overlap syndromes. Hepatology. 2001;33:994-1002. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Keaveny AP, Gordon FD, Khettry U. Post-liver transplantation de novo hepatitis with overlap features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chazouillères O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Montembault S, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapy. Hepatology. 1998;28:296-301. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rust C, Beuers U. Overlap syndromes among autoimmune liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3368-3373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klöppel G, Seifert G, Lindner H, Dammermann R, Sack HJ, Berg PA. Histopathological features in mixed types of chronic aggressive hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis. Correlations of liver histology with mitochondrial antibodies of different specificity. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977;373:143-160. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Okuno T, Seto Y, Okanoue T, Takino T. Chronic active hepatitis with histological features of primary biliary cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:775-779. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Davis PA, Leung P, Manns M, Kaplan M, Munoz SJ, Gorin FA, Dickson ER, Krawitt E, Coppel R, Gershwin ME. M4 and M9 antibodies in the overlap syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis and chronic active hepatitis: epitopes or epiphenomena? Hepatology. 1992;16:1128-1136. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Duclos-Vallée JC, Hadengue A, Ganne-Carrié N, Robin E, Degott C, Erlinger S. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. Corticoresistance and effective treatment by cyclosporine A. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1069-1073. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kumagi T, Alswat K, Hirschfield GM, Heathcote J. New insights into autoimmune liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:745-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hirschfield GM, Al-Harthi N, Heathcote EJ. Current status of therapy in autoimmune liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:11-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eaton JE, Talwalkar JA, Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis and advances in diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:521-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 14. | Al-Chalabi T, Portmann BC, Bernal W, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromes: an evaluation of treatment response, long-term outcome and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fallatah HI, Akbar HO. Autoimmune liver disease - are there spectra that we do not know? Comp Hepatol. 2011;10:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Czaja AJ. Current and future treatments of autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:269-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Teufel A, Galle PR, Kanzler S. Update on autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1035-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lindor K. Ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1524-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Angulo P, Batts KP, Therneau TM, Jorgensen RA, Dickson ER, Lindor KD. Long-term ursodeoxycholic acid delays histological progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:644-647. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Rodrigues CM, Fan G, Ma X, Kren BT, Steer CJ. A novel role for ursodeoxycholic acid in inhibiting apoptosis by modulating mitochondrial membrane perturbation. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2790-2799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loddenkemper C, Keller S, Hanski ML, Cao M, Jahreis G, Stein H, Zeitz M, Hanski C. Prevention of colitis-associated carcinogenesis in a mouse model by diet supplementation with ursodeoxycholic acid. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2750-2757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ozaslan E, Efe C, Heurgué-Berlot A, Kav T, Masi C, Purnak T, Muratori L, Ustündag Y, Bresson-Hadni S, Thiéfin G. Factors associated with response to therapy and outcome of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis with features of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:863-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |