Published online Feb 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1152

Revised: August 18, 2012

Accepted: September 19, 2012

Published online: February 28, 2013

One of the main changes of the current TNM-7 is the elimination of the category MX, since it has been a source of ambiguity and misinterpretation, especially by pathologists. Therefore the ultimate staging would be better performed by the patient’s clinician who can classify the disease M0 (no distant metastasis) or M1 (presence of distant metastasis), having access to the completeness of data resulting from clinical examination, imaging workup and pathology report. However this important change doesn’t take into account the diagnostic value and the challenge of small indeterminate visceral lesions encountered, in particular, during radiological staging of patients with colorectal cancer. In this article the diagnosis of these lesions with multiple imaging modalities, their frequency, significance and relevance to staging and disease management are described in a multidisciplinary way. In particular the interplay between clinical, radiological and pathological staging, which are usually conducted independently, is discussed. The integrated approach shows that there are both advantages and disadvantages to abandoning the MX category. To avoid ambiguity arising both by applying and interpreting MX category for stage assigning, its abandoning seems reasonable. The recognition of the importance of small lesion characterization raises the need for applying a separate category; therefore a proposal for their categorization is put forward. By using the proposed categorization the lack of consideration for indeterminate visceral lesions with the current staging system will be overcome, also optimizing tailored follow-up.

- Citation: Puppa G, Poston G, Jess P, Nash GF, Coenegrachts K, Stang A. Staging colorectal cancer with the TNM 7th: The presumption of innocence when applying the M category. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(8): 1152-1157

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i8/1152.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1152

Stage IV colorectal cancer (CRC) is no longer considered a single entity[1] and after several proposals for stratifying it[2,3] the current TNM-7 subdivides the M1 category into M1a (metastasis confined to one organ: liver, lung, ovary, non-regional lymph node(s) and M1b (metastasis in more than one organ or the peritoneum): accordingly stage IV is subdivided in IVA (Any T, Any N, M1a) and IVB (Any T, Any N, M1b)[4]. Population-based studies demonstrate that the prognosis for surgically resected stage IV disease is near identical for that of patients following potentially curative surgery for stage III disease[5].

The prognosis and treatment options (including increasingly used multimodality approaches) within the M1 stages depend largely on the extent and distribution of the metastases. Therefore, the current staging will be able to take into account improvements that have been made in surgical techniques for resectable metastases, and the impact of modern chemotherapy on rendering initially unresectable CRC liver metastases operable, while at the same time distinguishing between patients with a chance of cure at presentation and those for whom only palliative treatment is possible[3].

An other major change with the new TNM-7 is that the category ‘‘MX: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed’’ has been eliminated[4].

In this report, the change with the TNM-7 is discussed in a multidisciplinary setting and the diagnostic significance of small indeterminate visceral lesions encountered during radiological staging of patients with colorectal cancer is presented.

The resulting problems, in particular the ambiguities for stage assigning when applying the MX category and the risk of inaccurate staging and follow-up planning because of its elimination, are discussed. A proposal is presented for the categorization of such small, indeterminate visceral lesions.

There are basically two reasons for MX elimination. Firstly the MX category has been a source of misinterpretation, especially by pathologists (i.e., pMX) who “may assign MX, meaning that they cannot assess distant metastasis”[6]. This is a clinical, not pathological assessment. “If there are no obvious signs of metastasis, M0 or cM0 classifications are appropriate. In other words, once clinically examined, a patient is M0 until proven otherwise”[6] in analogy with the legal right Presumption of Innocence.

The second reason is that assigning the MX category prevents stage grouping by American cancer registries[6].

The elimination of MX allows only two categories, M0 (cM0): no distant metastasis and M1 (cM1 or pM1): distant metastasis[4] utilizing imaging and/or pathological assessment[7].

This goes against the TNM rule of assigning the X category, since the proper use of X is to denote the absence or uncertainty of assigning a given category[8] but importantly these are two different situations.

A similar clinical-pathological context is encountered when applying the R classification (R for residual as descriptor of ‘‘tumour remaining in the patient’’ after primary surgical resection): the assignment of the R classification must be performed “by a designated individual who has access to the complete data”[9].

Despite extensive clinical assessment of treatment results and careful pathologic examination, in some cases the presence of residual tumour cannot be assessed: the RX category applies[9,10].

If the pathologist hasn’t access to the preoperative clinico-radiological work-up, he/she can do only a limited staging (pT and pN), in the dark about these clinical data.

As an accurate pathological examination is the prerequisite for a prognostic staging and a tailored patient treatment, the enhanced search for additional prognostic factors applies in particular cases (problems with resection margins assessment; involvement of the peritoneum and/or adjacent structures or organs; suspicion for vascular invasion; few lymph nodes recovered; pericolonic tumour deposits)[11,12].

In this setting, patient characteristics, treatment-rel-ated features and disease extension as evaluated both during surgery and preoperatively are all relevant information.

In other words, the stage grouping, as well the risk assessment of patients belonging to the same stage, are better performed in the multidisciplinary setting than considered in isolation.

The major task of radiological staging is the exclusion (cM0) or detection (cM1) of metastases, particularly in the liver and/or the lung. The most frequently used imaging modalities for staging of CRC cancer patients are ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT (PET/CT)[13]. In the past 10 years, important advances have been made within all four techniques. While some (CT and PET/CT) will give patient specific information regarding abnormal masses and increased tissue metabolic activity throughout the body, others (MRI) will yield organ (liver) specific information and allow characterization of specific abnormalities to differentiate benign from malignant lesions. However, no single modality will diagnose all metastases, and the optimal imaging strategy to classify cM0 or cM1 depends on the clinical context, the organ site investigated, and the individual aims of oncologic care.

With the introduction of multidetector row CT (MDCT) scanning, CT imaging will continue to play the dominant role in the radiological staging of CRC patients[14]. Improved MDCT technologies have resulted in increased CT detection of small (< 1 cm) indeterminate lesions in the lung and/or liver (in around 10%-40% of CT CRC staging examinations)[15-20].

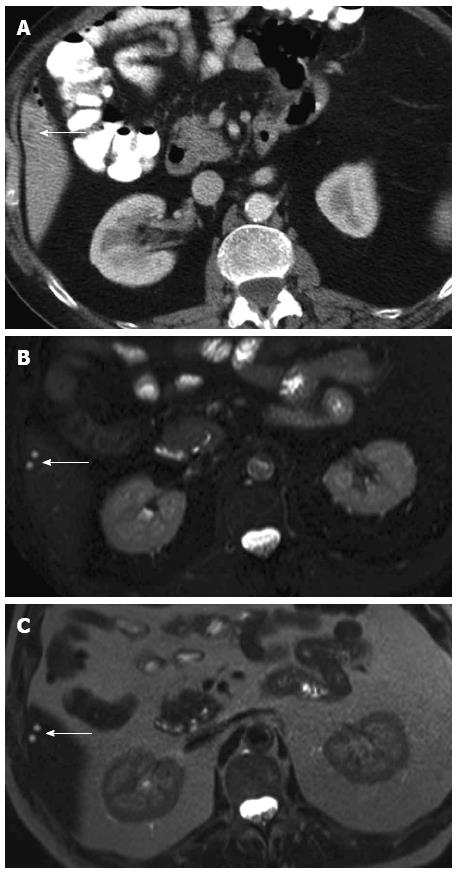

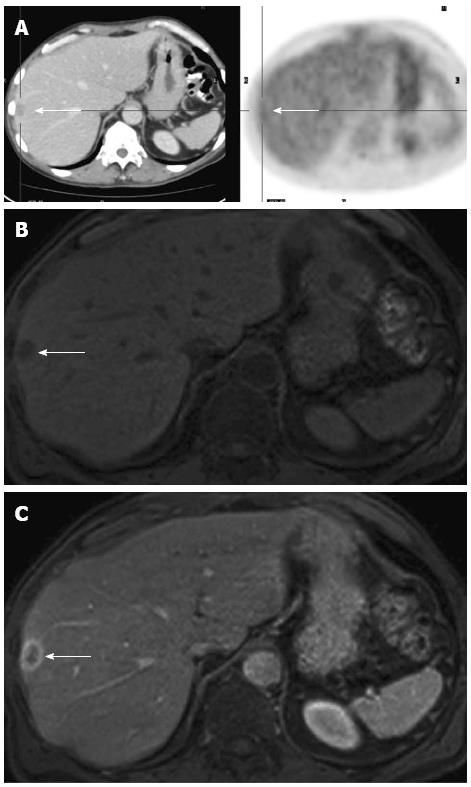

A major drawback of MDCT is that its ability to detect small lesions has outstripped its ability to characterize them. Although most tiny lung and/or liver lesions detected on CT staging of CRC patients are benign (Figure 1), 10%-20% of CT-indeterminate lung and/or liver lesions do develop into definite metastases (Figure 2)[17,18,20,21]. The M stage of CRC patients with CT-indeterminate lung and/or liver lesions, therefore, would require the category MX (“X” meaning uncertainty).

Regarding the definite diagnosis of whether or not these lesions are benign or malignant, consideration should include the T stage and the nodal status of the primary tumour and the distribution patterns of lesions as the probability of malignancy of small lung or liver lesions depends on the stage of the primary tumour (T stage) and the nodal status (N stage)[17,18].

Further evaluation with complementary imaging modalities is needed in patients with small CT-indeterminate lesions if a change of M staging would alter the treatment. In the thorax, additional PET/CT may be helpful in the differentiation of a single < 1 cm pulmonary lesion, but it may not be efficient when more than one small lesion is found on MDCT examination. In the liver, US may be the primary modality of choice in cases of advanced liver metastases, whereas contrast-enhanced US[22] MRI[23,24] and/or US-CT fusion imaging techniques[25] may complement the initial CT information in candidates for liver resection.

Follow-up CT imaging may be a reasonable approach in patients in whom a change of M staging would alter the clinical management, as malignant lesions would be expected to grow but benign lesions less so.

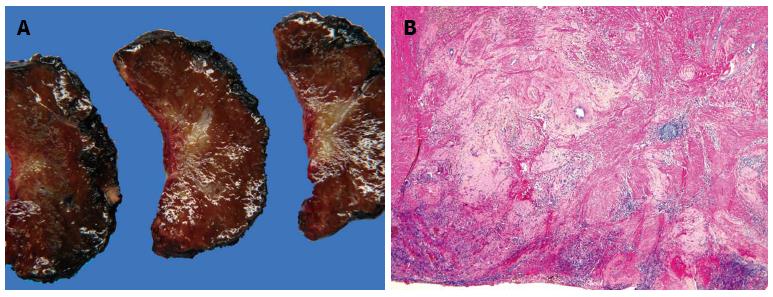

During restaging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, besides the complete clinical remission (disappearance on CT, ycM0) achieved in a small number of patients with metastases (mainly in CRC lung or liver metastases), small lesions, suspected as being residual tumour may be encountered (Figure 3): the difficulties in interpreting these lesions are made harder by the response to chemotherapy which may impact on the sensitivity of preoperative imaging studies in identifying all sites of disease[26].

Either chemotherapy itself, or the fatty infiltration it commonly causes, can affect the ability of CT to effectively restage patients, resulting in both false negative and false positive results; thus, in patients with known hepatic steatosis, or in patients receiving neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, liver MRI is often recommended for staging or restaging of hepatic disease[14].

However, only pathologic examination can determine the actual nature of these lesions (Figure 4).

Disease management for CRC has evolved in recent years into a multidisciplinary setting and is essentially based on tumour stage.

Cancer staging represents the operational basis for choosing the most appropriate therapy and for evaluating the efficacy of different therapeutic methods; it is an essential component of patient care, cancer research, and control activities, even in light of the impressive progress that has been attained in the fields of clinical strategies and molecular medicine.

The TNM system is subjected to continuous updating through an ongoing expert review of existing data.

Proposals for changes are made in different situations, including when the classification is poorly accepted, poorly used, or criticized in the literature[27]: here comes the decision for MX category elimination[6].

As the MX category results in ambiguity (lack of information or uncertainty in assigning a given category) both in applying and in interpreting it for stage assigning, it seems reasonable to abandon it.

This is also in accord with the general rule of the TNM system which states that, “if there is doubt concerning the correct category to which a particular patient should be allotted (T, N, or M), then the lower (i.e., less advanced) category should be used”[8].

However, the increased detection of small indeterminate lesions due to improved imaging technologies, particularly with MDCT imaging[20], suggests that a separate category is needed.

This is to avoid the application of M0 category to all indeterminate/suspicious lesions, with consequent reduced diagnostic accuracy and staging errors.

Cancer patients with small indeterminate lesions (e.g., in the lung and/or liver) are at risk of developing metastases and therefore need continued follow-up with imaging. The TNM staging system uses an extensive number of prefixes and suffixes, as additional descriptors, their presence indicating cases needing separate analysis[4] and ongoing investigation. We propose to add a suffix (e.g., iPUL, iHEP) to cM0 to indicate the presence of "small indeterminate lesions" considered to be benign but to be surveyed on further follow-up imaging to confirm that they are benign by their unchanged size and radiologic characteristics.

P- Reviewer Sipos F S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Poston G, Adam R, Vauthey JN. Downstaging or downsizing: time for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2702-2706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagashima I, Takada T, Nagawa H, Muto T, Okinaga K. Proposal of a new and simple staging system of colorectal liver metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6961-6965. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Poston GJ, Figueras J, Giuliante F, Nuzzo G, Sobrero AF, Gigot JF, Nordlinger B, Adam R, Gruenberger T, Choti MA. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4828-4833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind CH. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. New York: Wiley-Blackwell 2009; . |

| 5. | Morris EJ, Forman D, Thomas JD, Quirke P, Taylor EF, Fairley L, Cottier B, Poston G. Surgical management and outcomes of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1110-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sobin LH, Compton CC. TNM seventh edition: what’s new, what’s changed: communication from the International Union Against Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:5336-5339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jessup JM, Gunderson LL, Greene FL, Washington MK, Compton CC, Sobin LH, Minsky B, Goldberg RM, Hamilton SR. 2010 Staging System for Colon and Rectal Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1513-1517. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Greene FL, Brierley J, O’Sullivan B, Sobin LH, Wittekind C. On the use and abuse of X in the TNM classification. Cancer. 2005;103:647-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wittekind C, Compton CC, Greene FL, Sobin LH. TNM residual tumor classification revisited. Cancer. 2002;94:2511-2516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Puppa G, Bortolasi L, Colombari R, Sheahan K. Residual tumor (R) classification in colorectal cancer: reduced, expanded, or not uniform? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:288; author reply 289. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Puppa G, Sonzogni A, Colombari R, Pelosi G. TNM staging system of colorectal carcinoma: a critical appraisal of challenging issues. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:837-852. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Puppa G. TNM staging system of colorectal carcinoma: surgical pathology of the seventh edition. Diagn Histopathol. 2011;17:243-262. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bipat S, van Leeuwen MS, Comans EF, Pijl ME, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH, Stoker J. Colorectal liver metastases: CT, MR imaging, and PET for diagnosis--meta-analysis. Radiology. 2005;237:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Grand DJ, Beland M, Noto RB, Mayo-Smith W. Optimum imaging of colorectal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:909-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kronawitter U, Kemeny NE, Heelan R, Fata F, Fong Y. Evaluation of chest computed tomography in the staging of patients with potentially resectable liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:229-235. [PubMed] |

| 16. | McIntosh J, Sylvester PA, Virjee J, Callaway M, Thomas MG. Pulmonary staging in colorectal cancer--is computerised tomography the answer? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:331-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brent A, Talbot R, Coyne J, Nash G. Should indeterminate lung lesions reported on staging CT scans influence the management of patients with colorectal cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:816-818. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Christoffersen MW, Bulut O, Jess P. The diagnostic value of indeterminate lung lesions on staging chest computed tomographies in patients with colorectal cancer. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57:A4093. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Grossmann I, Klaase JM, Avenarius JK, de Hingh IH, Mastboom WJ, Wiggers T. The strengths and limitations of routine staging before treatment with abdominal CT in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McQueen AS, Scott J. CT staging of colorectal cancer: what do you find in the chest? Clin Radiol. 2012;67:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lim GH, Koh DC, Cheong WK, Wong KS, Tsang CB. Natural history of small, “indeterminate” hepatic lesions in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1487-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wilson SR, Burns PN. Microbubble-enhanced US in body imaging: what role? Radiology. 2010;257:24-39. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Motosugi U, Ichikawa T, Nakajima H, Sou H, Sano M, Sano K, Araki T, Iino H, Fujii H, Nakazawa T. Imaging of small hepatic metastases of colorectal carcinoma: how to use superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the multidetector-row computed tomography age? J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:266-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Coenegrachts K. Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver: New imaging strategies for evaluating focal liver lesions. World J Radiol. 2009;1:72-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Stang A, Keles H, Hentschke S, Seydewitz C, Keuchel M, Pohland C, Dahlke J, Weilert H, Wessling J, Malzfeldt E. Real-time ultrasonography-computed tomography fusion imaging for staging of hepatic metastatic involvement in patients with colorectal cancer: initial results from comparison to US seeing separate CT images and to multidetector-row CT alone. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:491-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Charnsangavej C, Clary B, Fong Y, Grothey A, Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1261-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gospodarowicz MK, Miller D, Groome PA, Greene FL, Logan PA, Sobin LH. The process for continuous improvement of the TNM classification. Cancer. 2004;100:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |