Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6842

Revised: August 1, 2013

Accepted: September 13, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 188 Days and 15.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the clinical characteristics of left primary epiploic appendagitis and to compare them with those of left colonic diverticulitis.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records and radiologic images of the patients who presented with left-sided acute abdominal pain and had computer tomography (CT) performed at the time of presentation showing radiological signs of left primary epiploic appendagitis (PEA) or left acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) between January 2001 and December 2011. A total of 53 consecutive patients were enrolled and evaluated. We also compared the clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, treatments, and clinical results of left PEA with those of left ACD.

RESULTS: Twenty-eight patients and twenty-five patients were diagnosed with symptomatic left PEA and ACD, respectively. The patients with left PEA had focal abdominal tenderness on the left lower quadrant (82.1%). On CT examination, most (89.3%) of the patients with left PEA were found to have an oval fatty mass with a hyperattenuated ring sign. In cases of left ACD, the patients presented with a more diffuse abdominal tenderness throughout the left side (52.0% vs 14.3%; P = 0.003). The patients with left ACD had fever and rebound tenderness more often than those with left PEA (40.0% vs 7.1%, P = 0.004; 52.0% vs 14.3%, P = 0.003, respectively). Laboratory abnormalities such as leukocytosis were also more frequently observed in left ACD (52.0% vs 15.4%, P = 0.006).

CONCLUSION: If patients have left-sided localized abdominal pain without associated symptoms or laboratory abnormalities, clinicians should suspect the diagnosis of PEA and consider a CT scan.

Core tip: The clinical symptoms of primary epiploic appendagitis (PEA) and acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) are similar in patients presenting with left-sided abdominal pain. In our study, the patients with PEA had well-localized abdominal tenderness, whereas those with ACD presented with slightly diffuse abdominal tenderness. The patients with ACD showed fever, rebound tenderness, and leukocytosis more often than those with PEA. When patients have well-localized abdominal tenderness without associated systemic manifestation or laboratory abnormalities, clinicians should suspect a diagnosis of PEA and consider a computer tomography (CT) scan. The characteristic CT findings of PEA may enable clinicians to accurately diagnose the disease.

-

Citation: Hwang JA, Kim SM, Song HJ, Lee YM, Moon KM, Moon CG, Koo HS, Song KH, Kim YS, Lee TH, Huh KC, Choi YW, Kang YW, Chung WS. Differential diagnosis of left-sided abdominal pain: Primary epiploic appendagitis

vs colonic diverticulitis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(40): 6842-6848 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i40/6842.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6842

Epiploic appendages are small pouches of peritoneum filled with fat and small vessels that protrude from the serosal surface of the colon[1-4]. Primary epiploic appendagitis (PEA) is an inflammation in the epiploic appendage caused by either torsion or spontaneous thrombosis of an appendageal draining vein[5-9].

PEA is a rare cause of localized abdominal pain in otherwise healthy patients. The only clinical feature of PEA is focal abdominal pain and tenderness, without pathognomonic laboratory findings. Clinically, it can be often mistaken for either diverticulitis or appendicitis, and may be treated with antibiotic therapy or even surgical intervention.

Historically, the diagnosis of PEA had been made at diagnostic laparotomy, performed for presumed appendicitis or diverticulitis with complications[7,8,10,11]. With advancements in radiologic techniques, such as ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT), PEA can be distinguished preoperatively due to its characteristic radiologic findings, and it is already being diagnosed increasingly[8,12].

Diverticulitis is the disorder most likely to be confused with PEA in a patient presenting with localized abdominal pain. In South Korea, as diverticulitis occurs much less in the left colon and PEA occurs quite frequently in the left colon; both diseases of the left colon remain difficult to differentiate.

Given that PEA is a benign and self-limited condition, the recognition of this diagnosis is important to clinicians to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations, antibiotic therapy, surgical interventions, and overuse of medical resources[7,10,13]. However, PEA cases are still infrequent and may often be missed even after imaging studies[8,10].

There are no previous studies specifically designed to compare the clinical characteristics of left PEA with those of left acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD). The present study was carried out to describe the clinical characteristics and characteristic CT findings of left PEA and to compare them with those of left ACD.

This study was performed on patients who presented with acute left-sided abdominal pain and diagnosed with left PEA or left ACD on CT findings at Konyang University Hospital from January 2001 to December 2011.

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records and CT images of the study patients after obtaining approval from the institutional review board with regard to the clinical characteristics, presumed diagnosis before the imaging studies, laboratory findings, radiologic findings, and treatments. If data for specific findings were missing, they were not included in the final analysis.

All official CT scans were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists to determine whether the imaging findings corresponded to PEA or ACD. We selected patients who were given the same diagnosis by two radiologists. The diagnosis of PEA was based on characteristic CT findings as shown below[10,11,14-16]: (1) ovoid fatty mass; (2) hyperattenuated ring sign; (3) disproportionate fat stranding; (4) bowel wall thickening with or without compression; (5) central hyperdense dot/line; and (6) lobulated appearance. The diagnosis of ACD was based on CT findings such as the presence of inflamed diverticula or thickened colonic wall more than 4 mm[7,16-18].

The left colon was defined as the segment of colon under the splenic flexure, which included the descending and sigmoid colon. The size of PEA was the largest diameter on the radiologic findings. The shapes were oval, semicircular, and triangular.

We evaluated symptom recurrence in the patients with PEA by reviewing the records of subsequent visits. One patient with PEA was lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), using the χ2 test and the Fisher’s exact test. The averages were compared by using the t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

There were 28 consecutive patients diagnosed as having left PEA on the CT reports and their clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age (mean ± SD) was 45.0 ± 11.6 years (range, 24-65 years), and they were more common in males (ratio of males to females = 16: 12). All the patients had sudden onset of abdominal pain. Two patients (7.1%) showed nausea and vomiting, and fever up to 38.3°C was present in two patients (7.1%). The abdominal tenderness was localized in the left lower (82.1%) and left upper (3.6%) quadrant. Rebound tenderness was found only in four patients (14.3%), and one patient (3.6%) showed palpable mass. The presumptive clinical diagnoses after medical history and physical examinations were ACD (57.1%), PEA (25.0%), acute gastritis (7.1%), ureter stone (3.6%), constipation (3.6%), and acute appendicitis (3.6%) (Table 2).

| Lt. PEA (n = 28) | Lt. ACD (n = 25) | P-value | |

| Mean age (yr) | 45.0 ± 11.6 | 58.8 ± 16.3 | 0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | 16/12 | 15/10 | 0.833 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.8 ± 3.3 | 24.9 ± 3.0 | 0.921 |

| Underlying disease (+) | 6 (21.4) | 10 (40.0) | 0.142 |

| Alcohol (+) | 14 (50.0) | 13 (52.0) | 0.884 |

| Smoking (+) | 11 (39.3) | 8 (32.0) | 0.581 |

| Sudden onset of abdominal pain (+) | 28 (100.0) | 25 (100.0) | NA |

| Duration of pain (d) | 3.8 ± 5.3 | 4.6 ± 4.1 | 0.537 |

| Nausea (+) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (8.0) | 1.00 |

| Vomiting (+) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (8.0) | 1.00 |

| Diarrhea (+) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0.098 |

| Fever (+) | 2 (7.1) | 10 (40.0) | 0.004 |

| Location of abdominal tenderness | 0.003 | ||

| Focal | 24 (85.7) | 12 (48.0) | |

| Lt. lower quadrant | 23 (82.1) | 11 (44.0) | |

| Lt. upper quadrant | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Diffuse | 4 (14.3) | 13 (52.0) | |

| Rebound tenderness (+) | 4 (14.3) | 13 (52.0) | 0.003 |

| Palpable mass (+) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Impression | Lt. PEA (n = 28) | Lt. ACD (n = 25) |

| PEA | 7 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ACD | 16 (57.1) | 15 (60.0) |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| Ureter stone | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastritis | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Constipation | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.0) |

| Appendicitis | 1 (3.6) | 1 (4.0) |

| Ischemic colitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| Cancer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) |

| Peritonitis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) |

| Enteritis (colitis) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (12.0) |

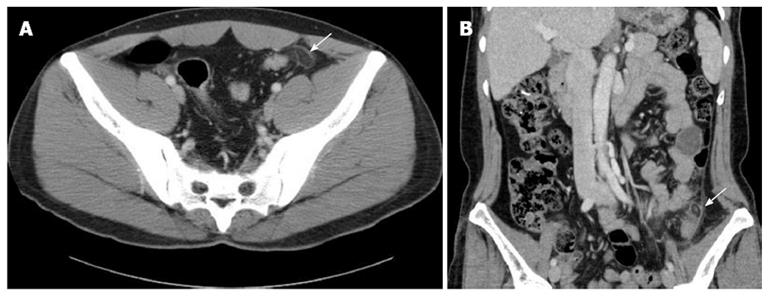

Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count up to 10000/mm3 was noticed in four of the 26 patients (15.4%). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were increased in two of the 13 patients (15.4%) and one of the 14 patients (7.1%), respectively. All patients underwent CT scans, and the average size of the PEA was 2.3 ± 0.6 cm (range, 1.0-3.7 cm). It was detected most frequently in the descending colon (64.3%), the sigmoid colon (25.0%), and the sigmoid-descending junction (10.7%) in that order. The characteristic CT findings (Figure 1A) were demonstrated in all patients; ovoid fatty mass was found in all patients (100%), hyperattenuated ring sign was detected in 25 patients (89.3%), disproportionate fat stranding was noticed in 4 patients (14.3%), bowel wall thickening with or without compression was observed in 6 patients (21.4%), and central hyperdense dot/line (Figure 1B) was detected in 5 patients (17.9%) (Table 3). We performed follow up CT scans in five patients between 1 and 3 wk, and they showed resolution of the inflammation.

| Features | Value |

| Location | |

| Descending colon | 18 (64.3) |

| Sigmoid-descending junction | 3 (10.7) |

| Sigmoid colon | 7 (25.0) |

| Size (mm) | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| Shape | |

| Oval | 22 (78.6) |

| Semicircular | 4 (14.3) |

| Triangular | 2 (7.1) |

| Computer tomography | |

| features | |

| Ovoid fatty mass | 28 (100.0) |

| Hyperattenuated ring sign | 25 (89.3) |

| Disproportionate fat stranding | 4 (14.3) |

| Bowel wall thickening±compression | 6 (21.4) |

| Central hyperdense dot/line | 5 (17.9) |

| Lobulated appearance | 0 (0.0) |

Surgical management was not required in any of the cases. Twenty-two patients (78.6%) were hospitalized, and the mean length of hospital stay was 5.4 ± 5.0 d (range, 0-24 d). Twenty-two patients (78.6%) received antibiotic therapy, and 6 patients (21.4%) were managed conservatively with hydration and mild analgesics. The duration of antibiotic therapy was 10.5 ± 8.4 d (range, 3-28 d) (Table 4). All patients had clinical follow up except one. No patient experienced symptoms of recurrence within the follow-up period (range, 21 d-105 mo).

| Lt. PEA (n = 28) | Lt. ACD (n = 25) | P-value | |

| Hospitalization | 22 (78.6) | 25 (100.0) | 0.014 |

| Treatment | 0.474 | ||

| Antibiotics | 22 (78.6) | 22 (88.0) | |

| Conservative management | 6 (21.4) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Duration of hospital stay (d) | 5.4 ± 5.0 | 10.2 ± 4.0 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of abdominal pain (d) | 3.3 ± 2.9 | 5.6 ± 3.6 | 0.012 |

| Duration of abdominal tenderness (d) | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 7.2 ± 3.8 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy (d) | 10.5 ± 8.4 | 16.5 ± 12.6 | 0.045 |

During the study period, 25 patients were diagnosed with left ACD. The mean age was 58.8 ± 16.3 years (range, 16-86 years), and 60.0% (15/25) of them were males. The major symptom was sudden onset of localized abdominal pain. Nausea occurred in two patients (8.0%), vomiting in two patients (8.0%), and fever in ten patients (40.0%). The abdominal tenderness was slightly diffuse over the left side of the abdomen (52.0%), and definite rebound tenderness was present in thirteen patients (52.0%) (Table 1). Laboratory tests showed that the WBC, ESR, and CRP were increased in thirteen of the 25 patients (52.0%), nine of the 12 patients (75.0%), and fifteen of the 20 patients (75.0%), respectively. All the patients were hospitalized, and the mean hospitalization period was 10.2 ± 4.0 d (range, 4-20 d). Except for three patients, all were treated with antibiotics (88.0%), and the mean duration of antibiotic therapy was 16.2 ± 12.6 d (range, 6-60 d) (Table 4).

The mean age was 13.8 years younger in patients with PEA than in ACD (45.0 ± 11.6 years vs 58.8 ± 16.3 years, P = 0.001). There were no significant differences on sex, body mass index, and underlying disease. All patients showed sudden onset of abdominal pain, but the location of the tenderness was different. In PEA, the pain was more localized (85.7% vs 48.0%, P = 0.003) in the left lower quadrant (LLQ) area (82.1%), whereas the pain was slightly diffuse throughout the left side of the abdomen in ACD (14.3% vs 52.0%, P = 0.003). Fever and rebound tenderness were more frequently noted in ACD, and this was statistically significant (7.1% vs 40.0%, P = 0.004; 14.3% vs 52.0%, P = 0.003; respectively) (Table 1). WBC, ESR, and CRP were more frequently increased in ACD, which were significantly different from those in PEA (15.4% vs 52.0%, P = 0.006; 15.4% vs 75.0%, P = 0.003; 7.1% vs 75.0%, P < 0.001; respectively).

The mean duration of hospital stay was about five days shorter (5.4 ± 5.0 d vs 10.2 ± 4.0 d, P < 0.001), and the mean duration of antibiotic therapy was 6-d shorter (10.5 ± 8.4 d vs 16.5 ± 12.6 d, P < 0.05) in PEA than in ACD (Table 4). Patients with PEA experienced an improvement of the abdominal pain and tenderness after 3.3 d on average, but in ACD, the abdominal pain and tenderness resolved more than 5 d after treatment. The pain duration was shorter in PEA than in ACD (3.3 ± 2.9 d vs 5.6 ± 3.6 d, P = 0.012; 3.3 ± 1.9 d vs 7.2 ± 3.8 d, P < 0.001; respectively) (Table 4).

Epiploic appendages, first described in 1543 by Vesalius, are small (1-2 cm thick, 0.5-5.0 cm long) pouches of fat-filled, serosa-covered structures present on the external surface of the colon[1-4]. These appendages have not been found to demonstrate any physiologic functions, but are presumed to serve as protective cushions during peristalsis or to provide a defensive mechanism against local inflammation like that of the greater omentum[2,9,13].

PEA, first introduced by Dockerty et al[6], is an ischemic inflammatory condition of the epiploic appendages without inflammation of adjacent organs. Each epiploic appendage has one or two small supplying arteries from the colonic vasa recta and has a small draining vein with narrow pedicle[2,9,14,19,20]. These appendages are susceptible to torsion due to their pedunculated shape with excessive mobility and limited blood supply[2,5,9]. PEA occurs usually from torsion of epiploic appendages which can result in ischemia, or spontaneous venous thrombosis of a draining vein[5-9].

PEA can occur at any age (reported range, 12-82 years[13]) with a peak incidence in the fourth to fifth decades, and men are slightly more affected than women[3,5,7,12,19,20]. In the current study, the mean age of patients with PEA was 45 years and there was a slight male predominance (16 male vs 12 female). They were younger than patients with ACD, and this is consistent with the results of previous studies[12].

Patients with PEA most commonly present with sudden onset of abdominal pain over the affected area, more often in the LLQ mimicking acute sigmoid diverticulitis[3,15,19,20]. They usually are afebrile and don’t have nausea or vomiting[2,7,8,19]. A well-localized abdominal tenderness is present in most patients on physical examination and rebound tenderness is also commonly detected[8,21]. A mass may be palpable in 10%-30% of patients[22]. In the present study, patients with PEA all showed sudden onset of abdominal pain, and the tenderness was well-localized in the LLQ area. Rebound tenderness was found only in 14.3%, and a palpable mass was noted in 3.6%. In ACD, the patients also had sudden onset of abdominal pain, but the tenderness was diffusely distributed throughout the left side of the abdomen. They more frequently presented with nausea, vomiting, fever, and rebound tenderness, which corresponded well with those of an earlier study[19].

There are no pathognomonic diagnostic laboratory findings in PEA. The WBC and ESR are normal or only moderately elevated[3,7,8,19]. In the current study, WBC, ESR, and CRP of the patients with PEA were elevated only in 7%-15% of patients. The patients with ACD more often showed elevations of WBC, ESR, and CRP.

Normal epiploic appendages are usually not identifiable at CT scan without surrounding intraperitoneal fluid such as ascites or hemoperitoneum[3]. These appendages typically have fat attenuations, but the attenuation is slightly increased when inflamed[2,7]. In the past, PEA has been diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy[7,8,10], but currently it may be possible to make the correct diagnosis with the pathognomonic radiologic findings before operation.

PEA can arise on any segment of the colon. The most frequently involved sites of PEA are the sigmoid colon[3,15] and the descending colon followed by the cecum[15,19], where they have more elongated epiploic appendages[23]. The characteristic CT finding of PEA is an ovoid fatty lesion with a hyperattenuated ring sign surrounded by inflammatory changes[9-11,14-16,24]. A high-attenuated central dot within the inflamed appendage was found in 42.9% by Ng et al[14], and in 54% by Singh et al[15]. It may be due to a thrombosed vessel in the epiploic appendages[8,10,11,14-16,25], or fibrous septa[26]. In addition, PEA can appear lobulated when two or more contiguous epiploic appendages lying in close proximity are affected[8,14,26], which would help to differentiate a PEA from an omental infarction[14]. In the present study, an ovoid fatty mass with a hyperattenuated ring sign was detected in most PEA patients (89.3%), which is similar to previous studies[8-10,14,15,23]. However, we did not find any lobulated appearing PEA on the CT scans.

The common presumptive clinical diagnosis for patients with PEA before radiologic interventions was either diverticulitis or appendicitis. Mollà et al[26] reported that 7.1% of patients investigated to exclude sigmoid diverticulitis had radiologic findings of PEA. Rao et al[10] reported that among eleven PEA found on CT scans, seven patients were initially misdiagnosed as having diverticulitis or appendicitis. In the current study, diverticulitis accounted for 57.1% of the presumptive diagnosis in patients with PEA. Only 25.0% of the patients were suspected of having PEA, most of which were made after the year 2005 when clinicians began to recognize this disease entity.

Early radiologic examination with an abdominal CT scan has aided in the differentiation of PEA from other diseases that require antibiotic therapy or surgical management[26]. With the increasing use of CT in the evaluation of an acute abdomen, the incidence of PEA is likely to increase as well[8,11,12]. In the present study, only four patients were diagnosed with PEA before 2005, and the rest were diagnosed after 2005.

PEA is a benign and self-limited condition with recovery occurring in less than 10 d without antibiotic therapy or surgery[7,10,13,23,26]. In general, patients with PEA can be managed conservatively with oral anti-inflammatory medications[7,8]. However, Sand et al[3] showed 40% recurrence rate in PEA. They believed that conservative treatment may lead to a tendency for recurrence and surgical interventions may be necessary for recurrent cases[3,12]. In the current study, most patients (78.6%) with PEA received antibiotic therapy due to the possibility of a more severe diagnosis. No recurrence was noted during the follow-up period, even in cases that were managed conservatively. The follow up CT scan for five patients showed resolution of PEA.

No previous studies were specifically designed to compare the clinical characteristics of patients presenting with left-sided abdominal pain. However, there are some limitations to this study, such as being a relatively small series, retrospective analysis, and no pathologic confirmation of PEA. Further prospective, larger, and comparative studies between left PEA and left ACD are needed.

In conclusion, the clinical symptoms of left PEA and left ACD are very similar in that both types of patients present with left-sided abdominal pain. Although PEA is rare, if a patient has a well-localized abdominal tenderness without associated fever, rebound tenderness, or laboratory abnormalities, we should suspect the diagnosis of PEA and early CT scans should be performed. PEA can show characteristic CT findings that may allow clinicians to diagnose it correctly and avoid unnecessary hospitalization, antibiotic therapy, or even surgical interventions.

Primary epiploic appendagitis (PEA) is a rare cause of localized abdominal pain. In the past, PEA has been diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy, but currently, it may be possible to make the correct diagnosis with the characteristic radiologic findings before operation. On clinical examination, left PEA can mimic left acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) owing to the lack of pathognomonic clinical features. No previous studies were specifically designed to compare the clinical characteristics of left PEA with those of left ACD.

PEA could be managed conservatively without antibiotic therapy or surgery, but ACD should be treated with antibiotics. Therefore, definitive diagnosis of PEA is important to avoid unnecessary hospitalizations, antibiotic therapy, or even surgical interventions. Early radiological examination with abdominal computer tomography (CT) is useful in obtaining an accurate diagnosis of PEA. The present study was designed to describe the clinical characteristics of left PEA and to compare them with those of left ACD. In addition, authors investigated the characteristic CT findings of PEA.

The patients with PEA and those with ACD all showed sudden onset of abdominal pain, but the location of the tenderness was different. The patients with PEA had a well-localized abdominal tenderness in the left lower quadrant area, whereas those with ACD presented with slightly diffuse abdominal tenderness throughout the left side of the abdomen. In the ACD cases, fever and rebound tenderness were more often noted, and white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels were more frequently increased. PEA showed characteristic CT findings like an ovoid fatty lesion with a hyperattenuated ring sign surrounded by inflammatory changes.

When patients have well-localized abdominal tenderness without associated systemic manifestation or laboratory abnormalities, clinicians should suspect a diagnosis of PEA and consider performing a CT scan. The data could be useful in obtaining an accurate diagnosis of PEA. The characteristic CT findings and specific clinical features of PEA make it easy to differentiate the disease from diverticulitis.

PEA is an ischemic inflammatory condition of the epiploic appendages without an inflammation of adjacent organs.

The authors demonstrated the clinical features and CT findings of PEA by comparison with those of ACD. The manuscript is well organized and well written.

P- Reviewer Miki K S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Liu XM

| 1. | Boardman J, Kaplan KJ, Hollcraft C, Bui-Mansfield LT. Radiologic-pathologic conference of Keller Army Community Hospital at West Point, the United States Military Academy: torsion of the epiploic appendage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghahremani GG, White EM, Hoff FL, Gore RM, Miller JW, Christ ML. Appendices epiploicae of the colon: radiologic and pathologic features. Radiographics. 1992;12:59-77. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Sand M, Gelos M, Bechara FG, Sand D, Wiese TH, Steinstraesser L, Mann B. Epiploic appendagitis--clinical characteristics of an uncommon surgical diagnosis. BMC Surg. 2007;7:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Subramaniam R. Acute appendagitis: emergency presentation and computed tomographic appearances. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:e53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carmichael DH, Organ CH. Epiploic disorders. Conditions of the epiploic appendages. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1167-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Dockerty MB, Lynn TE, Waugh JM. A clinicopathologic study of the epiploic appendages. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1956;103:423-433. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Legome EL, Belton AL, Murray RE, Rao PM, Novelline RA. Epiploic appendagitis: the emergency department presentation. J Emerg Med. 2002;22:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rioux M, Langis P. Primary epiploic appendagitis: clinical, US, and CT findings in 14 cases. Radiology. 1994;191:523-526. [PubMed] |

| 9. | ROSS JA. Vascular loops in the appendices epiploicae; their anatomy and surgical significance, with a review of the surgical pathology of appendices epiploicae. Br J Surg. 1950;37:464-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rao PM, Rhea JT, Wittenberg J, Warshaw AL. Misdiagnosis of primary epiploic appendagitis. Am J Surg. 1998;176:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rao PM, Wittenberg J, Lawrason JN. Primary epiploic appendagitis: evolutionary changes in CT appearance. Radiology. 1997;204:713-717. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Choi YU, Choi PW, Park YH, Kim JI, Heo TG, Park JH, Lee MS, Kim CN, Chang SH, Seo JW. Clinical characteristics of primary epiploic appendagitis. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:114-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vinson DR. Epiploic appendagitis: a new diagnosis for the emergency physician. Two case reports and a review. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:827-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ng KS, Tan AG, Chen KK, Wong SK, Tan HM. CT features of primary epiploic appendagitis. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Singh AK, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Rhea J, Mueller PR. CT appearance of acute appendagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1303-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Horton KM, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2000;20:399-418. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ferzoco LB, Raptopoulos V, Silen W. Acute diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1521-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hulnick DH, Megibow AJ, Balthazar EJ, Naidich DP, Bosniak MA. Computed tomography in the evaluation of diverticulitis. Radiology. 1984;152:491-495. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Son HJ, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Kim JS, Kim YH, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Paik SW, Rhee JC, Choi KW. Clinical diagnosis of primary epiploic appendagitis: differentiation from acute diverticulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:435-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Legome EL, Sims C, Rao PM. Epiploic appendagitis: adding to the differential of acute abdominal pain. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:823-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thomas JH, Rosato FE, Patterson LT. Epiploic appendagitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;138:23-25. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Shehan JJ, Organ C, Sullivan JF. Infarction of the appendices epiploicae. Am J Gastroenterol. 1966;46:469-476. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Singh AK, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Sagar P, Mueller PR, Novelline RA. Acute epiploic appendagitis and its mimics. Radiographics. 2005;25:1521-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McClure MJ, Khalili K, Sarrazin J, Hanbidge A. Radiological features of epiploic appendagitis and segmental omental infarction. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:819-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rao PM, Novelline RA. Case 6: primary epiploic appendagitis. Radiology. 1999;210:145-148. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Mollà E, Ripollés T, Martínez MJ, Morote V, Roselló-Sastre E. Primary epiploic appendagitis: US and CT findings. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:435-438. [PubMed] |