INTRODUCTION

Primary prostatic lymphoma is extremely rare, to the best of our knowledge, less than 200 cases have been described in the world literature so far[1], mostly as single case reports, and a few as large-series studies. It constitutes 0.09% of prostate neoplasms and 0.1% of all non-Hogdkin lymphomas[2]. The most common pathological type is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Because of unspecific clinical symptoms including increased urinary frequency, urinary urgency, occasional hematuria and acute urinary retention, primary prostatic lymphoma is easily misdiagnosed as benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostatitis, especially in elderly men, and it has a poor prognosis[3,4]. Serum prostate-pecific antigen (PSA) level is usually within normal limits in most patients. Due to the small number of patients reported, there is no consensus on the primary prostatic lymphoma management, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy and radical prostatectomy or combined strategies.

Here we report a case of primary DLBCL of the prostate incidentally found by 18F-fluoro-deoxy glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (PET/CT), and finally diagnosed by histopathological examination.

CASE REPORT

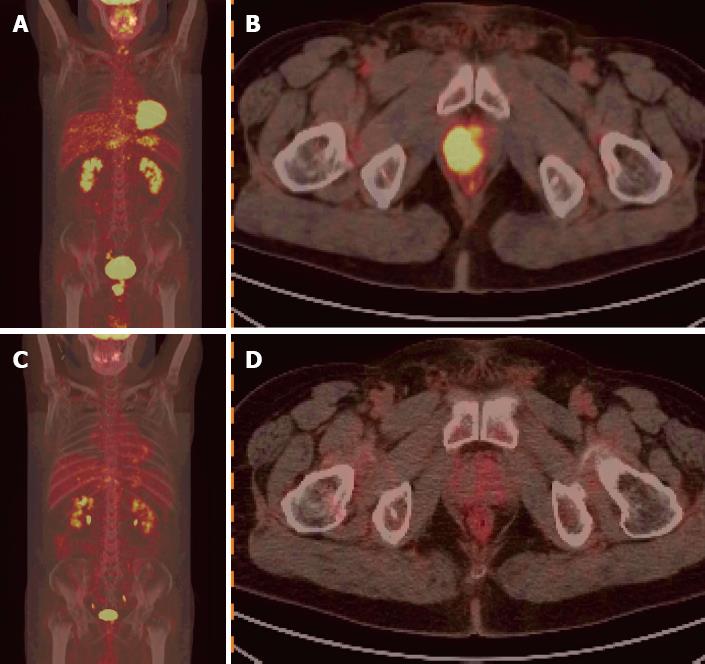

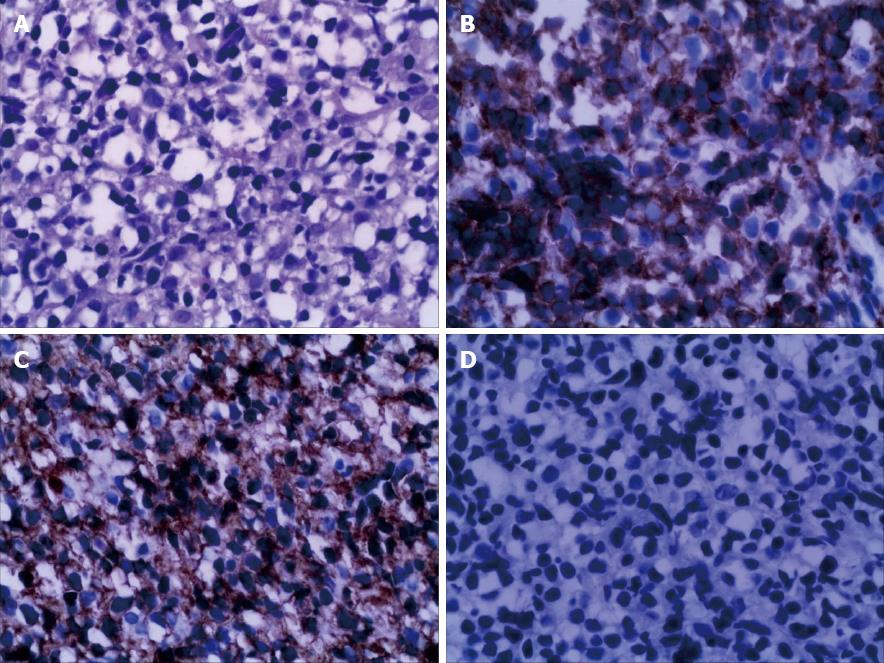

A 65-year-old man suffered from increased urinary frequency, urinary urgency, urinary endlessness and increased frequency of nocturia for two years. Because of his age and symptoms presenting as benign prostate hyperplasia, he did not take it seriously until the symptoms were aggravating. On examination, the prostate was palpable with degree II of hypertrophy, the median sulcus was shallow, and there was no hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory findings including blood count, liver and renal function were all normal. Chest X-ray revealed no abnormalities. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C was negative. Tumor markers like alpha-fetoprotein, carcino-embryonic antigen and total PSA were within normal limits. Ultrasound revealed prostatic hyperplasia and a hypoechoic lesion measuring 3.1 cm × 3.5 cm in size in the right lobe, and the nature of hypoechoic lesion was unidentified. Ultrasound-guided puncture was suggested. The patient was referred for a whole body PET/CT study to identify whether other sites were involved. He was injected with 9.8 millicuries of 18F-FDG and underwent a whole body scan with a dedicated PET/CT scanner. Except a nodal FDG uptake in the prostate gland with the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 12.7 (Figure 1A and B), all appeared unremarkable. In order to establish the diagnosis, ultrasound-guided transrectal puncture was performed. Biopsy specimens were composed of colorectal mucosal epithelium and aggregated lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical examination demonstrated that CD20 (+), CD79a (+), Pax5 (+), BCL-6 (+), mum-1 (+), and Ki-67 (+, 60%) were positive and CD10 (-), vim (+/-), CD3 (-), CD45RO (-), CD30 (-), CX (-), PSA (-), syn (-), and CGA (-) were negative. Combined morphological and immunophenotyping examinations confirmed a DLBCL of non-germinal center B-cell origin (Figure 2). Myeloproliferation was significant with nuclear shifted to the right, and red-giant cells hyperplasia was also active, and platelets were aggregately distributed, suggesting no evidence of bone marrow involvement. Consequently, Phase I and International Prognostic Index score 1 was considered. He experienced no taboos in chemotherapy, and completed six cycles of mabthera, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy. Three weeks after the end of chemotherapy, the patient underwent PET/CT scan again, which showed complete remission of the prostatic lesion on CT, with no active foci in the prostatic lesion on PET (Figure 1C, D), and the SUVmax was 2.0.

Figure 1 Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography image.

A: Whole body positron emission tomography (PET) image (scan) shows nodal hypermetabolic foci in the prostate, and no abnormally high uptake foci in the other sites of the body; B: The PET/computerized tomography (CT) fusion image displays a nodal hypermetabolic lesion located in the right lobe of the prostate, with maximal standardized uptake value (SUV) being 12.7; C: There were no hypermetabolic foci on the whole body PET imaging following six courses of chemotherapy; D: There was complete remission of the prostatic lesion after six cycles of chemotherapy, and the maximal SUV was 2.0.

Figure 2 Combined morphological and immunophenotyping examinations confirmed a diffuse large B cell lymphoma of non-germinal center B-cell origin.

A: Intensive proliferation of lymphoid cells (Hematoxylin and eosin, × 400); B and C: Diffuse and consistent expression of CD79a, CD20 (immunohistochemistry, × 400); D: The expression of serum prostate-pecific antigen is negative (immunohistochemistry, × 400).

DISCUSSION

Primary malignant lymphoma arising from the prostate is notably rare, We use PubMed search method, with key words of primary prostatic lymphoma, 87 Articles were retrieved by the end of Jan 2013, approximately 200 cases reported in the world literature[1]. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the major histological subtype of primary Hodgkin’s lymphoma (PHL) and DLBCL is the most common. Morphology of lymphoma in this case is typical, diffuse infiltrate lymphoid cells in prostate tissue. Immunohistochemical examination showed diffuse expression of CD79a and CD20 in tumor cell, which are the typical characteristics of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. CD3 being negative and diffuse expression of Mum-1 suggested that tumor cell originated from B cells. Moreover, CD30 being negative also tips for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Negative CK suggesting non epithelial malignancies, combined with negative PSA, exclude the possibility of prostate cancer. Positive bcl-6 indicates the biological activity of lymphoma, the proliferation fraction was 60% with Ki67 antibody. Combining these conditions together, a diagnosis of non germinal center origin of diffuse large B cell lymphoma was made. The three criteria for the diagnosis of primary prostatic lymphoma were as follows: (1) tumor limited to the prostate only; (2) the absence of any other lymphoid node or tissue involvement including blood vessels; and (3) a lymphoma free at an interval of at least 1 mo after diagnosis[5,6]. Since the clinical symptoms of primary prostatic lymphoma are atypical, including lower urinary tract symptoms, acute urinary retention or hematuria, it is difficult to establish a diagnosis merely based on clinical grounds, which may easily lead to a misdiagnosis as benign prostate hyperplasia or chronic prostatitis. Computerized tomography (CT) and Trans-Rectal UltraSound (TRUS) prostate plays an important role in the location and staging of the primary prostatic lymphoma, it usually manifests as the enlargement of the prostate with low density or hypoechoic lesions with or without abdominal and pelvic enlargement of lymph nodes on CT or US, in addition, CT and TRUS are also of great significance to treatment response to PPL[7,8], Gallium scan is optional when distant lymph node involvement was suspected[9]. There were no specific markers for Lymphoma at present, Prostatic Acid Phosphatase May be a sensitive tumor marker protein indicating development and progression of intravascular LBCL, which was a Subtype of diffuse LBCL[10]. Tumor marker like PSA usually is within normal range in most patients. The final diagnosis can be established by surgery or transrectal prostate biopsy.

Because of its rarity, there was no consensus on the optimal treatment of prostatic lymphoma at present. A recent study showed that R-CHOP chemotherapy is superior to CHOP and is the first choice for curative intent, this combination should become the standard for treating DLBCL[11-13]. Surgery or radiation is used only for palliative treatment of local symptoms and when the disease is confined to the prostate[14]. The prognosis of either primary or secondary prostatic lymphoma is poor and the median survival is around 23 mo after diagnosis[6]. If the disease is confined to the prostate, it could be cured with radiotherapy[3].

The use of FDG PET imaging is uncommon for prostatic lymphoma, and only four cases have been reported in the literature: two cases of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, revealing mild FDG uptake[15], and two cases of DLBCL, which showed intense hypermetabolism[16,17]. The extent of FDG uptake may be associated with histological types. In our case, the foci of the prostate demonstrated intense FDG uptake, which was similar to the cases reported.

18F-FDG PET/CT helped diagnose the possibility of PPL in this case, and demonstrated the absence of abnormal hypermetabolic foci in any other nodes or organs. 18F-FDG PET/CT identified significant treatment response after six cycles of chemotherapy.

In conclusion, 18F-FDG PET/CT is not only a complement to the conventional imaging studies, but also plays a significant role in the diagnosis and treatment of prostatic lymphoma. In short, when a nodal or diffuse uptake is observed in the prostate on PET/CT and PSA is within normal limits, primary prostate lymphoma should be taken into consideration except for prostatic cancer.

P- Reviewers Ribera JM, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Shah J S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Wang CH