Published online Oct 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6618

Revised: August 12, 2013

Accepted: September 4, 2013

Published online: October 21, 2013

Processing time: 121 Days and 2.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic common bile duct (CBD) stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter in 4 wk with or without a 2-wk course of anisodamine.

METHODS: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was undertaken. A total of 197 patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. Ninety-seven patients were assigned randomly to the control group and the other 100 to the anisodamine group. The anisodamine group received intravenous infusions of anisodamine (10 mg every 8 h) for 2 wk. The control group received the same volume of 0.9% isotonic saline for 2 wk. Patients underwent imaging studies and liver-function tests every week for 4 wk. The rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones was analyzed.

RESULTS: The rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones was significantly higher in the anisodamine group than that in the control group (47.0% vs 22.7%). Most (87.2%, 41/47) stone passages in the anisodamine group occurred in the first 2 wk, and passages in the control group occurred at a comparable rate each week. Factors significantly increasing the possibility of spontaneous passage by univariate logistic regression analyses were stone diameter (< 5 mm vs≥ 5 mm and ≤ 10 mm) and anisodamine therapy. Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that these two factors were significantly associated with spontaneous passage.

CONCLUSION: Two weeks of anisodamine administration can safely accelerate spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter, especially for stones < 5 mm.

Core tip: Common bile duct (CBD) stones are known to pass spontaneously in many patients. This phenomenon has not been given sufficient emphasis in terms of optimizing the timing of management of CBD stones. We investigated the rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter in 4 wk with or without a 2-wk course of anisodamine in a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anisodamine administration for 2 wk can safely accelerate spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter, especially for stones < 5 mm.

- Citation: Gao J, Ding XM, Ke S, Zhou YM, Qian XJ, Ma RL, Ning CM, Xin ZH, Sun WB. Anisodamine accelerates spontaneous passage of single symptomatic bile duct stones ≤ 10 mm. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(39): 6618-6624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i39/6618.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6618

Gallstone disease is one of the most common digestive diseases worldwide. Common bile duct (CBD) stones may develop in 3%-14.7% of patients who undergo cholecystectomy[1-4]. The stones can present in various ways or may be asymptomatic. Common symptoms of CBD stones include biliary colic, jaundice, acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis, or a combination of these symptoms[4].

Management of symptomatic CBD stones has evolved over the recent two decades and continues to evolve[5,6]. Before the advent of laparoscopy, patients with CBD stones requiring surgical treatment usually underwent laparotomy with CBD exploration and T-tube placement. Alternatively, they underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)/endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) by endoscopists[7-9] to avoid surgical CBD exploration. In recent years, laparoscopic CBD exploration has emerged as an alternative to ERCP/EST and a successor to open CBD exploration for the management of CBD stones[10-12].

The management strategy of CBD stones has focused mainly on the choice of treatment rather than timing. A consensus on the timing of management of symptomatic CBD stones is lacking. Most physicians, surgeons and endoscopists propose that symptomatic CBD stones should be extracted promptly[5]. However, accumulating evidence has shown that CBD stones often pass spontaneously, which raises the possibility of avoiding CBD intervention altogether[1,13-16]. The reported prevalence of spontaneous passage varies considerably, mainly because of different inclusion criteria and research methods used[1,13-15], but authors conclude that a significant portion of CBD stones may pass spontaneously with conservative treatment and do not need to be extracted by surgical or endoscopic means.

Spontaneous passage of CBD stones is dependent upon relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi. Hence, it is logical to use a medication to relax the sphincter of Oddi to accelerate the passage of CBD stones. Anisodamine, 6(s)-hydroxyhyoscyamine, is a belladonna alkaloid derived from the Chinese medicinal herb Scopolia tangutica Maxim of the Solanaceae family. It appears to be a non-selective M-cholinergic antagonist presumably capable of blockade at all M-choline receptor subtypes[17-23]. Little clinical information is available regarding its toxicity in humans. Based upon animal studies, it is less toxic than atropine or scopolamine[18]. Since the late 1970s in China, anisodamine has been employed almost exclusively as an OTC anti-spasmodic agent for relieving colic pain in the treatment of CBD stones[17].

We first attempted to use anisodamine to aid spontaneous passage of symptomatic CBD stones by prolonging its use to 2 wk in 2007, and noticed that it might accelerate their spontaneous passage. In 2009, we initiated a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to observe the rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm diameter in 4 wk with or without a 2-wk course of anisodamine.

This study was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing the rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter in 4 wk with or without a 2-wk course of anisodamine. The following hospitals in China participated in the study: Beijing Chaoyang Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; 254 Hospital of PLA, Tianjin, China; Chaoyang Central Hospital, Liaoning, China; and Zhanhua People’s Hospital, Shandong, China. Each center obtained approval from the responsible ethics committee according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki before the trial according to the current practice and guidelines in China. The first or primary approval of the study was obtained at the Beijing Chaoyang Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University. All research personnel and collaborators were trained accordingly.

All patients with CBD stones were informed of the currently available therapies to extract stones from the bile duct: ERCP/EST, laparoscopic surgery, or laparotomy. All patients were informed of the potential morbidity of each endoscopic or surgical procedure. All participants provided written informed consent for inclusion in the study. Patients were recruited into the study between January 2009 and April 2013.

Patients were enrolled if they met the following three inclusion criteria: (1) clinical presentation was consistent with biliary colic, cholangitis, jaundice, or/and acute pancreatitis. Jaundice was defined as a bilirubin level of > 50 μmol/L (normal range, 7-20 μmol/L). Acute pancreatitis was defined by at least two of the following criteria: characteristic abdominal pain, serum amylase and/or lipase values exceeding three times the upper limit of normal, and a computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating the characteristic changes of acute pancreatitis[24]; (2) abnormal liver function: high serum levels of aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, or γ-glutamyl transpeptidase of more than twice the normal values; and (3) a single CBD stone ≤ 10 mm in diameter confirmed by conventional CT or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Exclusion criteria were: (1) histories of emergency ERCP/EST or other procedures for severe cholangitis or pancreatitis; (2) CBD stones > 10 mm (which rarely passes spontaneously); and (3) contraindications to the use of anisodamine, such as glaucoma or cerebral hemorrhage.

Patients were assigned to the control group or anisodamine group by a computerized randomization process, and all patients were blinded to the allocation.

For patients with jaundice or isolated abnormal liver test results, a pharmacological strategy for protection against liver injury was adopted: vitamin E, vitamin C, glutathione and tiopronin. Patients with biliary colic were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain relief[25]. Patients with cholangitis were treated with antibiotics. For patients with acute pancreatitis, support measures were adopted: aggressive hydroelectrolytic replacement, analgesia and nutritional support treatment.

Patients in the anisodamine group received intravenous infusions of anisodamine (10 mg every 8 h) for 2 wk in addition to the treatments mentioned above. Anisodamine was terminated within the following 2 wk. Patients in the control group received the same volume of 0.9% isotonic saline for 2 wk in addition to the treatments mentioned above.

Patients who developed severe pancreatitis[24], severe cholangitis[26], or aggravated jaundice during this conservative treatment period dropped out of the study.

All data (demographic characteristics, nature of clinical presentation, imaging reports, and laboratory results) were collected for analyses by two trained physicians. Imaging reports were completed by two radiologists who had > 10 years of experience and were blinded to the allocation.

The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones in 4 wk. The secondary endpoints were the safety of anisodamine and the dropout rate.

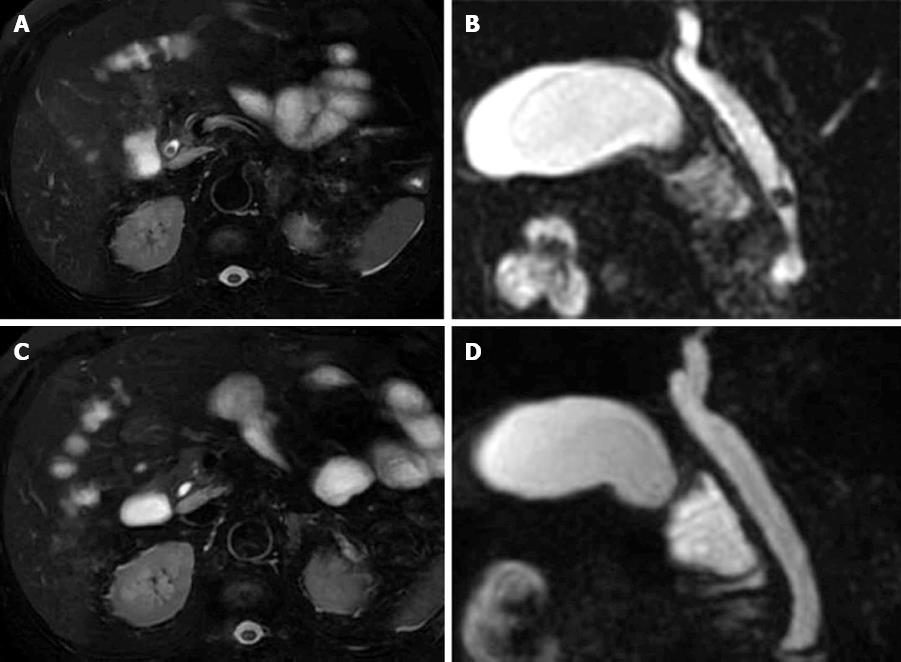

All patients underwent monitoring via conventional CT or MRCP and liver-function tests at a 1-wk interval for 4 wk. Spontaneous passage of CBD stones was defined as no signs of CBD stones upon CT or MRCP and normal results of liver function tests after conservative treatment.

Patients who experienced successful passage of CBD stones underwent only laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) without CBD intervention. However, if they did not experience successful passage, LC and laparoscopic CBD exploration via the transcystic or transduction route were performed. Patients with a history of cholecystectomy did not receive further treatment after successful passage of CBD stones. However, if the CBD stones failed to pass spontaneously, the patients underwent ERCP/EST.

Frossard et al[13] reported that the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones within 1 mo was 21%. We estimated that the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones was 20% because the patients and research methods in the present study were similar to those of Frossard et al[13]. Furthermore, the number of patients predicted to be necessary for statistical validity was based on the premise of improving the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones from 20% to 40%, with alpha set at 0.05 and beta set at 0.2, yielding a power of 80%. A two-tailed test was used. We calculated that 82 patients would be required in each arm of the study for a total projected study population of 164 patients. After taking a dropout rate of 20% into account, 197 patients would be required.

Continuous data are the mean ± SD, and an independent t test was used to examine differences between the two groups. Categorical variables were presented as number (%) and analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A stepwise logistic regression model was used to determine the effects of multiple factors on spontaneous passage. Significance was accepted at the 5% level. All CIs were reported at the 95% level. All statistical computations were undertaken using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences ver15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

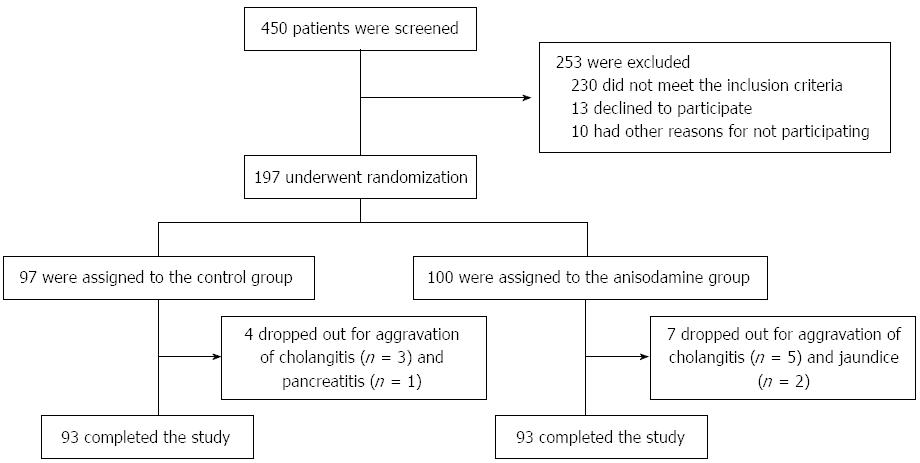

Of the 450 patients with CBD stones who were screened at the four participating hospitals of the study between January 2009 and April 2013, 197 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled (Figure 1). Ninety-one (46.2%) patients were male and 106 patients were female (53.8%). Ninety-seven patients were randomized to the control group, and 100 to the anisodamine group. No difference in baseline patient characteristics was observed between control and anisodamine groups (Table 1). During the period of conservative treatment, 11 (5.6%) patients (4 in the control group and 7 in the anisodamine group) dropped out because of aggravation of cholangitis (8 patients), pancreatitis (1 patient) and jaundice (2 patients). For these patients, laparoscopic cholecystostomy was carried out in 1 patient, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage in 2 patients, and ERCP/EST in 8 patients. There was no mortality in the 11 patients.

| Control group | Anisodamine group | P value | |

| (n = 97) | (n = 100) | ||

| Age (yr) | 59.1 ± 10.9 | 58.0 ± 12.4 | 0.564 |

| Sex | 0.422 | ||

| Male | 42 (43.3) | 49 (49.0) | |

| Female | 55 (56.7) | 51 (51.0) | |

| Main presentations | |||

| Biliary colic | 40 (41.2) | 44 (44.0) | 0.695 |

| Cholangitis | 25 (25.8) | 27 (27.0) | 0.845 |

| Jaundice | 20 (20.6) | 19 (19.0) | 0.776 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 12 (12.4) | 10 (10.0) | 0.597 |

| Median time interval from symptom onset to hospital admission | 0.606 | ||

| < 24 h | 84 (86.6) | 89 (89.0) | |

| ≥ 24 h and ≤ 48 h | 13 (13.4) | 11 (11.0) | |

| Imaging methods for diagnosis | 0.918 | ||

| Conventional CT | 82 (84.5) | 84 (84.0) | |

| MRCP | 15 (15.5) | 16 (16.0) | |

| Median diameter of CBD stone | 0.54 ± 0.24 | 0.55 ± 0.24 | 0.837 |

| Minimum, mm | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Maximum, mm | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Diameter of CBD stone | 0.959 | ||

| < 5 mm | 44 (45.4) | 45 (45.0) | |

| ≥ 5 mm and ≤ 10 mm | 53 (54.6) | 55 (55.0) | . |

| Median diameter of CBD | 12.6 ± 4.3 | 12.9 ± 3.8 | 0.683 |

| Minimum, mm | 8.0 | 8.3 | |

| Maximum, mm | 23.0 | 25.0 | |

| History of cholecystectomy | 0.856 | ||

| Yes | 27 (27.8) | 29 (29.0) | |

| No | 70 (72.2) | 71 (71.0) | |

Spontaneous passage of CBD stones occurred in 22.7% (22/97) and 47.0% (47/100) of patients in control and anisodamine groups, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 2, Table 2). For subgroup patients with stones < 5 mm in diameter, this rate was significantly higher in the anisodamine group than that in the control group (71.7% vs 31.8%, P < 0.05), and for those with stones of ≥ 5 mm and ≤ 10 mm, this rate was also significantly higher in the anisodamine group than that in the control group (27.3% vs 15.1%, P < 0.05) (Table 2). In the control group, the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones in each of the 4 wk was not significantly different (P > 0.05). In contrast, in the anisodamine group, the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones in the first 2 wk using anisodamine was significantly higher than that in the latter 2 wk without anisodamine treatment (P < 0.05), (Table 2). All 197 patients with symptomatic CBD stones experienced 1-3 attacks of biliary colic during follow-up. It was difficult to verify whether the stone passed during the colic attack or whether it passed silently.

| Diameter of CBD stone | Control group | Anisodamine group | P value |

| (n = 97) | (n = 100) | (intergroup) | |

| < 5 mm | 31.8% (15/44) | 71.1% (31/45) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 5 mm and ≤ 10 mm | 15.1% (7/53) | 27.3% (16/55) | 0.044 |

| Total | 22.7% (22/97) | 47.0% (47/100) | 0.000 |

| Within-group P | 0.014 | 0.000 | |

| Week 1 | 5.2% (5/97) | 17.0% (17/100) | 0.008 |

| Week 2 | 5.4% (5/92) | 28.9% (24/83) | 0.000 |

| Week 3 | 6.9% (6/87) | 5.1% (3/59)ac | 0.740 |

| Week 4 | 7.4% (6/81) | 5.4% (3/56)ac | 0.737 |

| Total | 22.7% (22/97) | 47.0% (47/100) | 0.000 |

| Within-group P | 0.907 | 0 |

Table 3 lists the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression models constructed to identify the predictors for spontaneous passage. Factors significantly increasing the possibility of spontaneous passage by univariate logistic regression analyses were the diameter of the CBD stone and anisodamine therapy. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analyses also revealed that the factors associated with spontaneous passage included the diameter of the CBD stone (OR = 3.095; 95%CI: 1.927-4.970; P = 0.000) and anisodamine therapy (OR = 3.534; 95%CI: 1.810-6.902; P = 0.000). Clinical presentation did not significantly influence the rate of spontaneous passage (Table 3).

| Parameters | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.141 | 0.735-1.724 | 0.534 | |||

| Sex | 0.980 | 0.545-1.763 | 0.947 | |||

| Main presentation | 1.001 | 0.754-1.328 | 0.994 | |||

| Diagnosis by imaging method | 0.976 | 0.438-2.177 | 0.954 | |||

| Diameter of CBD stone | 2.847 | 1.819-4.458 | 0.000 | 3.095 | 1.927-4.970 | 0.000 |

| Median diameter of CBD | 1.331 | 0.726-2.041 | 0.342 | |||

| History of cholecystectomy | 1.070 | 0.557-2.054 | 0.839 | |||

| Anisodamine treatment | 3.023 | 1.632-5.600 | 0.000 | 3.534 | 1.810-6.902 | 0.000 |

| Median time interval from onset to hospital admission | 0.596 | 0.252-1.412 | 0.240 | |||

Among the 69 patients whose CBD stones passed spontaneously, 50 patients with gallstones underwent LC and avoided CBD intervention, and the other 19 patients with a history of cholecystectomy did not receive additional treatment. Among the 117 patients who failed to pass CBD stones, 85 patients with gallstones underwent LC and laparoscopic CBD exploration (56 trans-ductal and 29 trans-CBD), and 32 patients with a history of cholecystectomy underwent ERCP/EST to remove CBD stones. No patient underwent conversion to open surgery. Exploration of the CBD and common hepatic duct in all of these patients found stones, which were removed using a Dormia basket or flushed into the duodenum. The CBD was closed over an appropriately sized T-tube in 29 patients by incising and opening the CBD directly with stone retrieval after the stones were removed under endoscopic visualization. T-tube cholangiography was undertaken 21 d or later postoperatively, and the T-tube was removed if abnormalities were not observed.

Tachyarrhythmia, palpitations, blurred vision and severe retention of urine were not observed in the anisodamine group. Of 100 patients in the anisodamine group, 11 patients experienced a dry mouth occasionally, which disappeared immediately after withdrawal of anisodamine.

This study was designed to investigate the rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones with the aid of a 2-wk course of anisodamine in symptomatic patients to demonstrate the role of conservative treatment for symptomatic CBD stones. The results of the study showed that 47.0% (47/100) of CBD stones passed spontaneously in the anisodamine group, and 87.2% (41/47) of the passages occurred in the first 2 wk with anisodamine treatment. However, only 22.7% (22/97) of patients passed CBD stones spontaneously in the control group, with comparable rates of spontaneous passage each week. Multivariate analyses indicated that anisodamine therapy carried a substantial advantage for accelerating the spontaneous passage of CBD stones. Moreover, stones < 5 mm in diameter were more likely to pass spontaneously, and spontaneous passage was not related to the clinical presentation. This finding would be useful for clinicians to predict which patients might pass stones spontaneously and to make rational clinical judgments.

Most clinicians specializing in hepatobiliary medicine are familiar with spontaneous passage of CBD stones, and such passage is recognized in the literature[1,13-16]. Collins et al[1] reported that 12/34 of silent CBD stones confirmed by intraoperative cholangiography in selective LC passed spontaneously 6 wk after the procedure. Frossard et al[13] evaluated the prevalence and time-course of CBD stone passage in symptomatic patients by analyzing discrepancies between endoscopic ultrasonography and ERCP as a function of the time elapsed between these two procedures. They found that the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones was 21% (12/57), and that the rates of spontaneous passage in different periods (from 6 h to 3 d and from 3 to 27 d) were 21% (8/37) and 20% (4/20), respectively. They also concluded that stone diameter was the only factor that predicted passage, and that the rate of spontaneous passage of stones with a diameter of > 8 mm was only 4.3% (2/47). Tranter et al[14] conducted a study in 1000 patients to determine the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones and related it to the various presentations of CBD stones. They found that 390/532 CBD stones passed spontaneously, but they did not specify the observation period. Lefemine et al[15] retrospectively investigated 108 patients presenting with jaundice due to CBD stones, and found that spontaneous passage of CBD stones occurred in 60 (55.6%) of 108 patients within approximately 4 wk. The inclusion criteria of the latter two studies[14,15] were not strict: patients with a history of jaundice, pancreatitis, abnormal results of liver function tests, or a dilated CBD were assumed to have a history of CBD stones. Therefore, the reported rates of spontaneous passage were probably overestimated.

Reported rates of spontaneous passage of CBD stones vary mainly because of different inclusion criteria and research methods used[1,13-15]. However, studies have demonstrated that a significant portion of CBD stones can pass spontaneously through the sphincter of Oddi into the duodenum with conservative treatment. However, further investigation is required to clarify the true potential of spontaneous passage of symptomatic CBD stones of different diameters because this potential is related closely to clinical decision-making for patients with symptomatic CBD stones. The present study was the first randomized study to investigate the rate of spontaneous passage in selected patients with CBD stones with the aid of a 2-wk course of anisodamine, and no studies have focused on other pharmacologic therapies for CBD stones. We showed not only the rate of spontaneous passage of CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in the control arm, but also confirmed that anisodamine effectively and safely accelerated the spontaneous passage of CBD stones in these patients.

Tranter et al[14] found that spontaneous passage of CBD stones occurred more commonly in patients with pancreatitis, biliary colic, and cholecystitis, but less commonly in jaundiced patients. They explained that patients with jaundice may be treated more quickly than other patients, allowing less time for spontaneous passage. The present study did not support this finding. We did not identify a particular characteristic of the patients who failed to pass stones spontaneously during the same observation period. Therefore, we concluded that spontaneous passage was not related to the presentation.

The limitation of this study was that the attending physicians were not blinded to the patient allocation. To address this, all physicians underwent strict and standardized training based on the treatment protocol. This training stressed that all patients should be treated with the same demeanor regardless of their randomized treatment arm.

In conclusion, 2 wk of anisodamine administration can safely accelerate spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter in symptomatic patients. These findings suggest that conservative treatment may be regarded as first-line management for these patients, especially for those with a stone < 5 mm.

Common bile duct (CBD) stones are known to pass spontaneously in many patients. This phenomenon has not been given sufficient emphasis in terms of optimizing the timing of management of CBD stones. Anisodamine has been used as an antispasmodic agent for relieving colic pain in the treatment of CBD stones in China for more than 40 years. The authors hypothesized that anisodamine therapy can accelerate the passage of CBD stones by relaxing the sphincter of Oddi. The rate of spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in 4 wk with or without a 2-wk course of anisodamine, was investigated.

The management of CBD stones has focused mainly on the choice of treatment rather than its timing. Consensus on the timing of management of symptomatic CBD stones is lacking. Most physicians, surgeons and endoscopists propose that symptomatic CBD stones should be extracted promptly. However, accumulating evidence has shown that CBD stones often pass spontaneously, which raises the possibility of avoiding CBD intervention.

The results of the present study suggested that anisodamine administration for 2 wk can safely accelerate spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in symptomatic patients. These findings indicated that conservative treatment could be the first-line management for these patients, especially for those with stones < 5 mm in diameter.

The results of the present study suggest that 2 wk of anisodamine administration can safely accelerate spontaneous passage of single and symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter in symptomatic patients. These findings indicated that conservative treatment could be the first-line management for these patients, especially for those with stones < 5 mm.

The authors undertook a randomized controlled trial investigating if anisodamine accelerated spontaneous passage of single symptomatic CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter. The study was well conducted and the results are interesting that 47.0% of CBD stones ≤ 10 mm in diameter passed spontaneously with the aid of a 2-wk course of anisodamine.

P- Reviewers Endo I, Ladas SD S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hemli JM, Arnot RS, Ashworth JJ, Curtin AM, Simon RA, Townend DM. Feasibility of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration in a rural centre. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:979-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Petelin JB. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1705-1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Almadi MA, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Management of suspected stones in the common bile duct. CMAJ. 2012;184:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brown LM, Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Brasel KJ, Inadomi JM. Cost-effective treatment of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis and possible common bile duct stones. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:1049-1060.e1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao HC, He L, Zhou DC, Geng XP, Pan FM. Meta-analysis comparison of endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation and endoscopic sphincteropapillotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3883-3891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Tantau M, Mercea V, Crisan D, Tantau A, Mester G, Vesa S, Sparchez Z. ERCP on a cohort of 2,986 patients with cholelitiasis: a 10-year experience of a single center. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:141-147. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jang SE, Park SW, Lee BS, Shin CM, Lee SH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, Park JK. Management for CBD stone-related mild to moderate acute cholangitis: urgent versus elective ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2082-2087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Grubnik VV, Tkachenko AI, Ilyashenko VV, Vorotyntseva KO. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus open surgery: comparative prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2165-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yachimski P, Poulose BK. ERCP vs laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for common bile duct stones: are the 2 techniques truly equivalent? Arch Surg. 2010;145:795; author reply 795-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lu J, Cheng Y, Xiong XZ, Lin YX, Wu SJ, Cheng NS. Two-stage vs single-stage management for concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3156-3166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Frossard JL, Hadengue A, Amouyal G, Choury A, Marty O, Giostra E, Sivignon F, Sosa L, Amouyal P. Choledocholithiasis: a prospective study of spontaneous common bile duct stone migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:175-179. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Spontaneous passage of bile duct stones: frequency of occurrence and relation to clinical presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lefemine V, Morgan RJ. Spontaneous passage of common bile duct stones in jaundiced patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:209-213. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Itoi T, Ikeuchi N, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T. Spontaneous passage of bile duct stone, mimicking laying an egg (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1389; discussion 1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wu SD, Kong J, Wang W, Zhang Q, Jin JZ. Effect of morphine and M-cholinoceptor blocking drugs on human sphincter of Oddi during choledochofiberscopy manometry. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:121-125. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Poupko JM, Baskin SI, Moore E. The pharmacological properties of anisodamine. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sun L, Zhang GF, Zhang X, Liu Q, Liu JG, Su DF, Liu C. Combined administration of anisodamine and neostigmine produces anti-shock effects: involvement of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:761-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang YB, Fu XH, Gu XS, Wang XC, Zhao YJ, Hao GZ, Jiang YF, Fan WZ, Wu WL, Li SQ. Safety and efficacy of anisodamine on prevention of contrast induced nephropathy in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:1063-1067. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Geng W, Fu XH, Gu XS, Wang YB, Wang XC, Li W, Jiang YF, Hao GZ, Fan WZ, Xue L. Preventive effects of anisodamine against contrast-induced nephropathy in type 2 diabetics with renal insufficiency undergoing coronary angiography or angioplasty. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:3368-3372. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Guoshou Z, Chengye Z, Zhihui L, Jinlong L. Effects of high dose of anisodamine on the respiratory function of patients with traumatic acute lung injury. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;66:365-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ye N, Li J, Gao C, Xie Y. Simultaneous determination of atropine, scopolamine, and anisodamine in Flos daturae by capillary electrophoresis using a capillary coated by graphene oxide. J Sep Sci. 2013;36:2698-2702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4323] [Article Influence: 360.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 25. | Colli A, Conte D, Valle SD, Sciola V, Fraquelli M. Meta-analysis: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in biliary colic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1370-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fujii Y, Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Yano K, Imamura N, Nagano M, Hiyoshi M, Otani K, Kai M, Kondo K. Verification of Tokyo Guidelines for diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |