Published online Apr 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2080

Revised: January 4, 2013

Accepted: January 11, 2013

Published online: April 7, 2013

Processing time: 134 Days and 1.1 Hours

AIM: To compare synchronous laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) combined with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and sequential LC combined with EST for treating cholecystocholedocholithiasis.

METHODS: A total of 150 patients were included and retrospectively studied. Among these, 70 were selected for the synchronous operation, in which the scheme was endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with EST during LC. The other 80 patients were selected for the sequential operation, in which the scheme involved first cutting the papillary muscle under endoscopy and then performing LC. The indexes in the two groups, including the operation time, the success rate, the incidence of complications, and the length of the hospital stay, were observed.

RESULTS: There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of the numbers of patients, sex distribution, age, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, serum bilirubin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, mean diameter of common bile duct stones, and previous medical and surgical history (P = 0.54, P = 0.18, P = 0.52, P = 0.22, P = 0.32, P = 0.42, P = 0.68, P = 0.70, P = 0.47 and P = 0.57). There was no significant difference in the surgical operation time between the two groups (112.1 ± 30.8 min vs 104.9 ± 18.2 min). Compared with the sequential operation group, the incidence of pancreatitis was lower (1.4% vs 6.3%), the incidence of hyperamylasemia (1.4% vs 10.0%, P < 0.05) was significantly reduced, and the length of the hospital stay was significantly shortened in the synchronous operation group (3 d vs 4.5 d, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: For treatment of cholecystocholedocholithiasis, synchronous LC combined with EST reduces incidence of complications, decreases length of hospital stay, simplifies the surgical procedure, and reduces operation time.

-

Citation: Ding YB, Deng B, Liu XN, Wu J, Xiao WM, Wang YZ, Ma JM, Li Q, Ju ZS. Synchronous

vs sequential laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholecystocholedocholithiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(13): 2080-2086 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i13/2080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2080

Cholelithiasis, including cholecystolithiasis and common bile duct stones (CBDSs), is common in clinical practice. The incidence of concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs is 10%-33%, and varies according to age[1]. Cholelithiasis can be associated with serious complications, including biliary pancreatitis and suppurative cholangitis. Therefore, it is important to regularize and improve the process of clinical diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

Laparotomy for gallbladder excision, with common bile duct (CBD) exploration or endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) through duodenal papilla, was once the standard treatment plan for concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. In the past 10 years, with the rapid development of laparoscopic techniques, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the main treatment for cholecystolithiasis. However, many studies have shown that LC combined with laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) has a high success rate (up to 83%-89%) for concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. It also has many merits, such as a significantly shortened hospital time and synchronous minimally invasive surgery[2-6]. Moreover, there is no significant difference in the incidence of complications with this technique when compared with EST[7]. Unfortunately, it is not widely applied because of the complex surgical technique[3,8].

With the rapid development of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), a variety of operations can be chosen on the basis of the LC scheme for concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDS. Besides LC with LCBDE, the so-called double endoscopy joint operation is also an option, which comprises LC combined with ERCP and EST before, during, or after the operation to remove CBDSs[9-11]. The most widely used operation scheme is LC combined with preoperative ERCP and EST. This scheme often requires two hospitalizations, longer hospital stays, and correspondingly higher medical costs. Even after strict preoperative screening, a proportion of CBDS cases with preoperative diagnoses is still found to be biliary stone negative during the ERCP process. Therefore, some patients must pay unnecessary ERCP-related medical expenses and undergo potential risks of surgery[12]. In recent years, there have been reports on the laparoendoscopic rendezvous (LRV) operation to treat concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. The LRV operation has the advantages of high stone clearance, a low incidence of complications, and reduced hospital time, but it also has disadvantages that include a complex surgical procedure and a longer single operation time[13,14].

In our study, we used synchronous LC combined with EST to treat concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. This approach combined LRV with conventional surgical procedures to perform endoscopic retrograde bile duct intubation. We compared the efficacy and safety of synchronous LC with LRV vs sequential LC with the conventional operation.

A total of 167 patients with cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs were enrolled in this study from June 2009 to October 2012 at the Second Clinical Medical School, Yangzhou University. The preliminary diagnosis was established by the clinical symptoms (abdominal pain and vomiting), signs (right upper-quadrant abdominal pain and jaundice), serum biochemical index (high bilirubin or transaminase level), and abdominal ultrasound (gallstones and suspicious CBDSs, or CBD diameter > 8 mm). All of these cases were further examined by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to diagnose cholecystolithiasis and choledocholithiasis.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) age > 80 years or < 18 years; (2) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score[15] ≥ 4; (3) suppurative cholangitis (body temperature > 38.5 °C, with right upper-quadrant abdominal pain and pressure pain, or hyperbilirubinemia); (4) acute pancreatitis (serum amylase 3 times higher than normal); (5) pregnancy; (6) abdominal surgical history; and (7) decompensated cirrhosis that is not suitable for endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery.

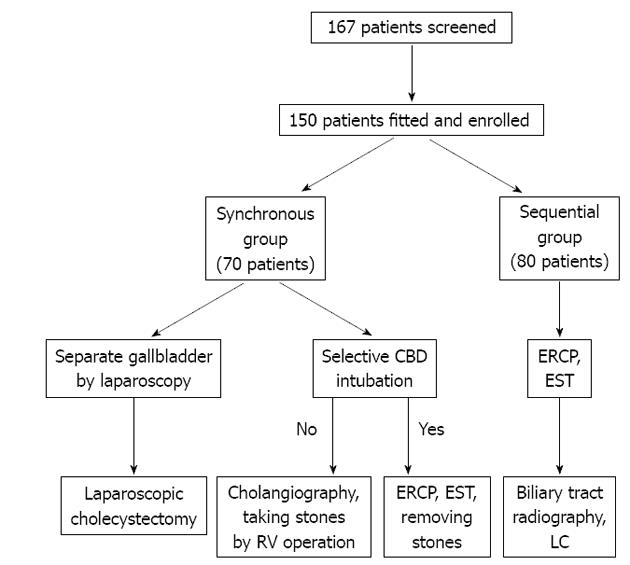

A total of 150 patients were retrospectively studied and the treatment procedure is shown in Figure 1. Among these, 70 were selected for the synchronous operation, in which ERCP was combined with EST during LC. The other 80 patients were selected for the sequential operation, in which the papillary muscle was cut under endoscopy, and then LC was performed after 24-72 h. All ERCPs were performed by one of two endoscopic technologists, while LC was performed by one of three expert surgeons. Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Clinical Medical School, Yangzhou University, and signed informed consent was obtained from each patient for the operative procedures.

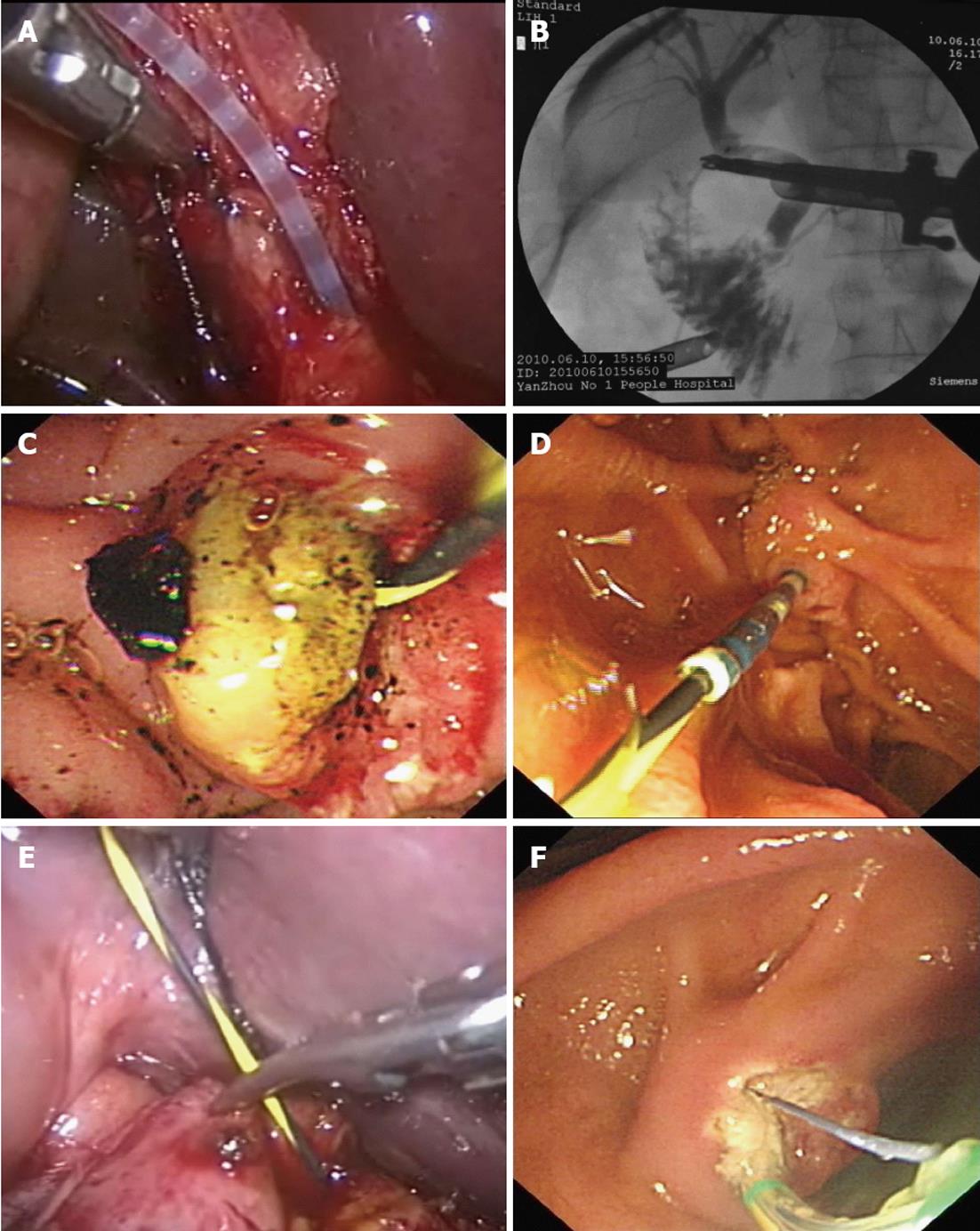

The entire procedure was performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Patients in the synchronous group were placed on a C-arm-compatible table. Pneumoperitoneum was routinely established and laparoscopic instruments were put into the peritoneal cavity. The triangle of Calot was first dissected, then the gallbladder artery was ligated close to the gallbladder side, the gallbladder duct was exposed and cut open near the CBD side to make an oblique incision, and the angiographic catheter was inserted (Figure 2A). The contrast agent was injected to confirm the presence of bile duct stones (Figure 2B). The duodenoscope was inserted into the descending part of the duodenum, and a selective CBD intubation was made. Stones were removed by balloon or basket after successful intubation, and lithotripsy or balloon expansion was carried out if it was difficult to remove the stones (Figure 2C). If selective bile duct intubation failed, a yellow zebra guide wire was intubated using an angiographic catheter under laparoscopy (Figure 2D). The yellow zebra was across the duodenal papilla to the descending part of duodenum (Figure 2E), drawn out, and plugged into the duodenum again with the end of guide wire. The duodenoscope was inserted in the descending part of duodenum through the mouth, and the guide wire was pulled out with the duodenal trap of the duodenoscope. The duodenal papillary muscle was cut with an incision knife, which followed the guide wire retrograde to the duodenal papilla (Figure 2F). Gas inside the gastrointestinal tract was exhausted at the end of the endoscopic operation, the gallbladder duct was ligated by routine laparoscopic procedure, and the gallbladder was removed.

Patients in the sequential operation group were placed in the left supine or prone position. The duodenoscope was inserted, and radiography was performed to confirm the situation of the biliary tract. The duodenal papillary muscle was cut, and stones were removed by balloon or basket. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was performed and biliary tract radiography was completed during 24-48 h. Residual stones were removed, and LC was carried out if no residual stone was observed.

Operation time was defined as the time from anesthesia to when the patient awoke after the operation in the synchronous group. In the sequential group, the operation time was the sum of the time for the ERCP operation before LC and the LC operation time. Major complications were defined as any intraoperative or postoperative (42 d) events that altered the clinical course, such as ERCP complications (including pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia, perforation, and bleeding) and LC complications (bile duct leakage, bleeding, pneumonia, and organ failure).

The success rate included the ERCP and LC success rates. ERCP success was defined as smoothly cannulating the CBD and achieving complete CBD stone clearance at the time of final cholangiography. LC success was defined as performing LC smoothly without converting to open surgery. Postoperative hospitalization time was the hospital time for LC combined with ERCP in the synchronous group, while it was the length of the hospital stay after ERCP in the sequential group.

Patients were scheduled for follow-up 2 and 6 wk after surgery. During that time, no patients were lost to follow-up. The patients were reviewed by color ultrasound and for liver function. MRCP was performed if there was a question of residual bile duct stones, and stones were removed by remedial ERCP if they were confirmed.

The SPSS software package (versions 17.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of the numbers of patients, sex distribution, age, ASA score, serum bilirubin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, mean diameter of CBDSs, and previous medical and surgical history (P > 0.05 each).

| Synchronous group | Sequential group | P value | |

| Total patients | 70 | 80 | |

| M/F ratio | 46/24 | 53/27 | 0.54 |

| Mean age, yr | 59.0 (38-75) | 56.6 (36-74) | 0.18 |

| ASA score (I-II/III) | 62/8 | 70/10 | 0.52 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Abdominal pain | 59 (84.3) | 72 (90.0) | 0.22 |

| Jaundice | 51 (71.4) | 62 (77.5) | 0.32 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 39 (55.7) | 47 (58.8) | 0.42 |

| Mean serum bilirubin, mg/dL | 5.4 (0.5-24) | 5.9 (0.6-27) | 0.68 |

| Mean γ-GGT, μ/dL | 116.2 (27-342) | 122.8 (35-396) | 0.70 |

| MRCP diagnosis | |||

| Mean diameter of CBDS, mm | 9.7 (7-21) | 9.2 (6-20) | 0.47 |

| Stone number (single/multi) | 49/21 | 56/24 | 0.57 |

| Mean operative time, min | 112.1 ± 30.8 | 104.9 ± 18.2 | 0.08 |

| Success rate | |||

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy | 70 (100) | 77 (96.3) | 0.15 |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 69 (98.6) | 80 (100) | 0.74 |

| Major complications rate | |||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (1.4) | 5 (6.3) | 0.14 |

| Hyperamylasemia | 1 (1.4) | 8 (10) | 0.03 |

| Bleeding/perforation/infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hospital stay, d | 3 (2-6) | 4.5 (3-12) | < 0.001 |

The intraoperative and postoperative parameters are shown in Table 1. The mean operation time in the synchronous group was 112.1 ± 30.8 min. The LRV operation was performed in 15 cases, because it was difficult to complete selective bile duct intubation during the endoscopic process, and the average operation time of the 15 cases was 132.3 ± 29.0 min. The mean ERCP operation time in the sequential operation group was 38.4 ±12.1 min, the LC operation time was 66.6 ± 14.4 min, and the overall operation time was 104.9 ± 18.2 min. There was no significant difference in the average operation time between the two groups (P > 0.05).

The hyperamylasemia incidence in the synchronous group was 1.4% (1/70), and 10.0% (8/80), in the sequential group, and there was a significant difference in incidence between the two groups (P < 0.05). The incidence of acute pancreatitis in the synchronous group was 1.4% (1/70) and 6.3% (5/80) in the sequential group, and there was a trend toward significance between the two groups (P > 0.05). Bleeding, perforation, death, and serious complications were not observed in either of the groups. The acute pancreatitis that occurred after the operation was mild, and it did not develop into severe pancreatitis after timely treatment.

The length of the hospital stay in the sequential group was 4.5 d (range, 3-12 d), and five patients with acute pancreatitis had lengthened hospital stays. The length of hospital stay in the synchronous group was 3 d (range, 2-6 d), which was significantly lower than that in the sequential group (P < 0.001).

All 150 patients were followed up for a mean 65 wk (range, 8-135 wk). At the 6-wk follow up, color Doppler ultrasound, liver function tests, and MRCP did not identify recurrence of stones and complications related to the operation, except for one patient in the synchronous group. This patient was readmitted 8 wk after the LRV procedure with residual choledocholithiasis and treated successfully with repeat ERCP and CBD clearance.

LC combined with EST is the most commonly used minimally invasive treatment for concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDS[16,17]. LC combined with postoperative EST is an important remedial treatment measure for stones, which appear in LC but are not removed by instant LCBDE. Its weakness is that EST has a greater need for operative success because, if EST fails to remove stones, patients could require additional surgical procedures. The success rate of ERCP is 85%-90%[18]. Even if the postoperative ERCP is successful, the hospitalization time is longer than for synchronization[19,20]. The scheme in most medical units is conventional LC combined with preoperative ERCP, which also has some disadvantages. Even if the preoperative ERCP is successful in removing the stones, the few cases for which LC fails still require laparotomy. If preoperative ERCP is complicated by acute pancreatitis, it is not possible to perform LC. In this study, there were five patients with acute pancreatitis in the sequential group for whom LC had to be delayed, and these patients had extended hospital stays. In addition, intraoperative exploration confirms only 27%-54% of stones, in spite of the clinical history characteristics, medical examination, serum biochemical index, abdominal ultrasound diagnosis, and CBDS preoperative examination, which means that a considerable proportion of patients incur unnecessary ERCP-related medical expenses and potential risks of surgery[12]. The ERCP serious complication rate was 2.5%-11%, and the mortality rate was 0.5%-3.7%[18].

In recent years, there have been reports that synchronous ERCP and EST are carried out in LC to treat concurrent cholecystolithiasis with CBDSs[21]. One meta-analysis of 27 published intraoperative ERCP studies including a total of 795 patients by La Greca et al[22] showed that the operation success rate was 69.2%-100%, with an average of 92.3%; the average intraoperative endoscopic operation time was 35 min; and the average surgical operation time was 104 min. In these 27 studies, 4.7% of cases required laparotomy, the complication incidence was 5.1%, and the mortality rate was 0.37%. Intraoperative synchronous EST in LC has no obvious differences in terms of complications, such as acute pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia, compared with sequential LC and EST operations, but it significantly improves the operation success rate, shortens the average hospitalization time, and decreases the medical treatment charges[23]. A randomized study with 120 cases of concurrent cholecystolithiasis with CBDSs observed the risk factors of postoperative ERCP-related pancreatitis, and found that no case was complicated by acute pancreatitis in synchronous surgery, and six patients suffered from iatrogenic acute pancreatitis in sequential surgery[24]. These data suggest that the synchronous operation has the advantages of high stone clearance, high success rate, and a low complication rate for treating CBDSs when compared to sequential double endoscopy.

Although synchronous surgery has obvious advantages, its implementation faces a few difficulties. First, the synchronous double endoscopy combined operation mostly uses the LRV operation during laparoscopic transcystic intubation into the filar guide and can extend the operation time. A clinical study with 45 patients showed that the average time for double endoscopy synchronous surgery was 119.09 ± 14.4 min[13]. Another study showed that the operation time for LC combined with intraoperative ERCP was 192.0 ± 8.9 min, which was 85 min longer than for separate laparoscopic gallbladder resection and CBD exploration[14]. In the beginning, we used the LRV operation, which is similar to the approach used by ElGeidie’s team[25]. We found that there were certain difficulties in the operation that extended the time required. Now, we prefer LC combined with conventional endoscopic retrograde bile duct intubation, and turn to the LRV operation when there is difficulty in selective intubation. This method can avoid associated risks, including acute pancreatitis and bleeding caused by repeated intubation, contrast agent injection, and pre-cut sphincterotomy. It can also simplify the operation process and reduce the time. In our study, there were difficulties during the selective intubation of 15 patients in the synchronous operation group, so we turned to the LRV operation. There was no difference in the operation time between the synchronous and sequential treatment groups. The incidence of hyperamylasemia and iatrogenic pancreatitis was lower in the synchronous than in the sequential operation group. Besides the operation time, time was required for the positional adjustment of the X-ray machine and endoscopic equipment by the operators. This timing can be addressed after improving the surgical process. Second, the synchronous operation required cooperation between the surgeons and endoscopic physicians. The latter must perform intraoperative ERCP immediately and synchronously with surgery once biliary angiography has confirmed CBDSs. Thus, we can try to reduce the operation time. However, clinical practice often faces certain difficulties. All of the cases in our study were diagnosed with CBDSs by MRCP preoperatively, because the surgeons, endoscopic physicians, and equipment were in the right place from the beginning. This design guaranteed the effective organization of the synchronous double endoscopy operation. The sensitivity and specificity of MRCP diagnosis in CBDS are 95% and 97%, respectively[26], and all cases diagnosed with CBDSs by MRCP were confirmed in the perioperative period in this study. Third, some researchers think that general anesthesia by endotracheal intubation is an unfavorable factor in duodenoscopy operations[15], so we used general anesthesia by nasal intubation to reduce this negative influence.

Our study also had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study that was not performed in a double-blind and randomized fashion. Second, our work was in the preliminary stage, and it did not assess the learning curves for the two types of surgery. Third, the length of follow up was short, and the number of patients was small. Therefore, further studies with larger patient populations are needed to draw more valid conclusions.

In conclusion, we found that both synchronous and sequential laparoscopic operations combined with endoscopic operations were minimally invasive surgical procedures for effective treatment of concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. Moreover, the synchronous double endoscopy combined operation may selectively apply the LRV scheme. Synchronous surgery has advantages, such as reducing complications and shortening hospital stay, and it can also simplify the operation process and reduce the time required.

We are grateful for the work of members in the Departments of Gastroenterology and Surgery. We thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

Cholecystolithiasis, combined with common bile duct stones (CBDSs), is common in clinical practice. In the management of cholelithiasis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the treatment of choice, but the ideal management of choledocholithiasis with LC is controversial. Today a number of options exist, including endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) before LC, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, and postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Several studies have shown the efficacy of the combined laparoendoscopic rendezvous (LRV) technique for treatment of cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs. Studies have demonstrated that this method has advantages of easier cannulation, prevention of pancreatic trauma, and reduced hospital time, but it also has disadvantages, including a complex surgical procedure and a longer single operation time.

In this study, the authors used synchronous LC combined with EST to treat concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDS, with selective application of the LRV procedure. Study data showed that synchronous surgery had advantages, such as reducing complications and shortening hospital stay, and it also simplified the surgical procedure and reduced the operation time in most cases.

Elective application of the LRV procedure in a synchronous double endoscopy combined operation is a minimally invasive surgical procedure for the effective treatment of concurrent cholecystolithiasis and CBDSs.

LRV is a technique in which the sphincterotome is driven across the papilla into the choledochus by a Dormia basket passed into the duodenum through the cystic duct during LC.

This was a well-designed retrospective study in which the authors compared the efficacy and safety of synchronous LC with LRV vs sequential LC with the conventional operation. The results are interesting and suggest that synchronous surgery has advantages, such as reducing complications, and shortening operation time and hospital stay.

P- Reviewers Feo CV, Sari YS S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Memon MA, Hassaballa H, Memon MI. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: the past, the present, and the future. Am J Surg. 2000;179:309-315. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Chander J, Vindal A, Lal P, Gupta N, Ramteke VK. Laparoscopic management of CBD stones: an Indian experience. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:172-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Poulose BK, Speroff T, Holzman MD. Optimizing choledocholithiasis management: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:43-48; discussion 49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berthou JCh, Dron B, Charbonneau P, Moussalier K, Pellissier L. Evaluation of laparoscopic treatment of common bile duct stones in a prospective series of 505 patients: indications and results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1970-1974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Paganini AM, Guerrieri M, Sarnari J, De Sanctis A, D’Ambrosio G, Lezoche G, Lezoche E. Long-term results after laparoscopic transverse choledochotomy for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:705-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sgourakis G, Lanitis S, Karaliotas Ch, Gockel I, Kaths M, Karaliotas C. [Laparoscopic versus endoscopic primary management of choledocholithiasis. A retrospective case-control study]. Chirurg. 2012;83:897-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hong DF, Xin Y, Chen DW. Comparison of laparoscopic cholecystectomy combined with intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct for cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:424-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gholipour C, Shalchi RA, Abassi M. Efficacy and safety of early laparoscopic common bile duct exploration as primary procedure in acute cholangitis caused by common bile duct stones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:634-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schiphorst AH, Besselink MG, Boerma D, Timmer R, Wiezer MJ, van Erpecum KJ, Broeders IA, van Ramshorst B. Timing of cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2046-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, Mackersie RC, Rodas A, Kreuwel HT, Harris HW. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Rábago LR, Ortega A, Chico I, Collado D, Olivares A, Castro JL, Quintanilla E. Intraoperative ERCP: What role does it have in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ghazal AH, Sorour MA, El-Riwini M, El-Bahrawy H. Single-step treatment of gall bladder and bile duct stones: a combined endoscopic-laparoscopic technique. Int J Surg. 2009;7:338-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enochsson L, Lindberg B, Swahn F, Arnelo U. Intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to remove common bile duct stones during routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not prolong hospitalization: a 2-year experience. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tenconi SM, Boni L, Colombo EM, Dionigi G, Rovera F, Cassinotti E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as day-surgery procedure: current indications and patients’ selection. Int J Surg. 2008;6 Suppl 1:S86-S88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shojaiefard A, Esmaeilzadeh M, Ghafouri A, Mehrabi A. Various techniques for the surgical treatment of common bile duct stones: a meta review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:840208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Costi R, Mazzeo A, Tartamella F, Manceau C, Vacher B, Valverde A. Cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a case-control study comparing the short- and long-term outcomes for a “laparoscopy-first” attitude with the outcome for sequential treatment (systematic endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy). Surg Endosc. 2010;24:51-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Coppola R, Riccioni ME, Ciletti S, Cosentino L, Ripetti V, Magistrelli P, Picciocchi A. Selective use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to facilitate laparoscopic cholecystectomy without cholangiography. A review of 1139 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1213-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Williams GL, Vellacott KD. Selective operative cholangiography and Perioperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a viable option for choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:465-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lu J, Cheng Y, Xiong XZ, Lin YX, Wu SJ, Cheng NS. Two-stage vs single-stage management for concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3156-3166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | La Greca G, Barbagallo F, Sofia M, Latteri S, Russello D. Simultaneous laparoendoscopic rendezvous for the treatment of cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:769-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Morino M, Baracchi F, Miglietta C, Furlan N, Ragona R, Garbarini A. Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy versus laparoendoscopic rendezvous in patients with gallbladder and bile duct stones. Ann Surg. 2006;244:889-93; discussion 893-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lella F, Bagnolo F, Rebuffat C, Scalambra M, Bonassi U, Colombo E. Use of the laparoscopic-endoscopic approach, the so-called “rendezvous” technique, in cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a valid method in cases with patient-related risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:419-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | ElGeidie AA, ElEbidy GK, Naeem YM. Preoperative versus intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for management of common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1230-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Verma D, Kapadia A, Eisen GM, Adler DG. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |