Published online May 31, 2019. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v7.i5.224

Peer-review started: April 3, 2019

First decision: April 30, 2019

Revised: May 11, 2019

Accepted: May 22, 2019

Article in press: May 26, 2019

Published online: May 31, 2019

Processing time: 58 Days and 20.9 Hours

A minor subset of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) can also arise outside the gastrointestinal tract, which is known as an extra-GIST (E-GIST). Primary GIST of the liver is an exceptional location.

To characterize epidemiological, clinical and pathological features and options of treatments.

We performed a systematic review to search for articles on primary hepatic GIST.

This review shows that right hepatic lobe was the most frequent location. Regarding pathological and immunohistochemical features, mitotic count was ≥ 5/50 High Power Fields in more than 50%; and CD117 was negative in only 1 patient. More than 70% of patients had a lesion with high risk of malignancy.

The diagnosis of E-GIST must be considered in a liver mass. Rendering an accurate diagnosis is a challenge, as well as the confirmation of their primary or metastatic nature.

Core tip: A great majority of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) outside the gastrointestinal tract (GI) are metastases; however, a minor subset of primary GISTs can also arise outside the GI tract which is known as an extra-GIST (E-GIST). Among E-GIST, liver is an exceptional location. We systematically review the literature on primary GIST of the liver. Primary hepatic EGISTs have a male predominance and usually are incidental findings. The surgical approach is commonly performed, and the final diagnosis is made by pathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis. Primary hepatic EGISTs are often high-risk lesions. Literature is scarce and it is very difficult to establish guidelines for clinicians.

- Citation: Manuel-Vázquez A, Latorre-Fragua R, de la Plaza-Llamas R, Ramia JM. Hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Systematic review of an exceptional location. World J Meta-Anal 2019; 7(5): 224-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v7/i5/224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v7.i5.224

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are a group of mesenchymal tumors characterized by the expression of KIT protein (CD117), with an overall incidence between 10-20 per million, which harbor different clinical behavior[1,2]. These are the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract, which represent 0.1%-3% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms[3,4].

Regarding the pathogenesis, GISTs are believed to originate from interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), the pacemaker of gastrointestinal tract[5-7], or to a common precursor cell of ICCs and smooth muscle cells[8]. So, GISTs may arise anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract. Approximately 60%-70% of GIST occurs in the stomach, followed by 20%-30% in small intestine; colon and rectum (5%), esophagus (< 2%) and appendix are less frequent[9,10].

A great majority of GISTs outside the GI tract are metastases from GI GISTs; however, a minor subset of primary GIST can also arise outside the GI tract which is known as an extra-GIST (E-GIST). According to Miettinen et al[11], the frequency of EGISTs is no higher than 1% of all GISTs of defined origin, and they are characterized by the same morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular characteristic than conventional GIST[12].

Regarding embryology, the origin of EGISTs remains controversial, with certain hypotheses. Since some researchers have observed “ICC-like” cells with a similar structure and function to ICCs in organs outside of the GI tract[13,14], it is reasonable to presume that EGISTs originate from this common precursor cells of ICC. Other authors suggest that EGISTs may originate from a pool of undifferentiated pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells located outside GI tract, and then differentiate into ICCs[15-17].

Among E-GIST, mesentery, retroperitoneum and pancreas are the most frequent and this type of tumor has been reported in the omentum, bladder, gallbladder and uretus also; while, primary GIST of the liver is an exceptional location and its definitive diagnosis requires ruling out other types of liver mesenchymal tumors and other tumor types, such as sarcoma[6,12,15].

Most studies of E-GISTs are case reports, lacking enough information to clarify the disease; therefore, it is very difficult to establish guidelines for clinicians. In addition, if we refer to primary hepatic E-GIST, the literature is much scarcer due to this exceptional location.

This study is a systematic review of the literature on primary GIST of the liver. Our aim is to identify clinical and diagnostic features and treatment in this exceptional location of this type of mesenchymal tumor.

We performed a search for articles on primary hepatic GIST in MEDLINE (PubMed), Tripdatabase, and Cochrane Library databases, with no restrictions on publication dates or author up until January 31, 2019.

The search items comprise the following MESH terms: “Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors” OR “extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor” OR “extra-gastrointestinal stromal neoplasm” OR “extra-gastrointestinal stromal neoplasms” OR “E-GIST” OR “E-GISTs” and the following no MESH terms: “Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver” OR “Primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor” OR “Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver”.

The articles were included or rejected based on the information obtained from the title and summary, and in case of doubt, after reading the complete article.

To evaluate the quality of the studies selected, we used the scale designed by Manterola et al[18] which evaluates each publication individually depending on the type of study, the sample size, and the methodology used. It has a range of 6 to 36 points, with a quality cutoff point of 18. We carried out a qualitative analysis of the studies included and their conclusions, based on the levels of evidence and degrees of recommendation proposed by Cook et al[19].

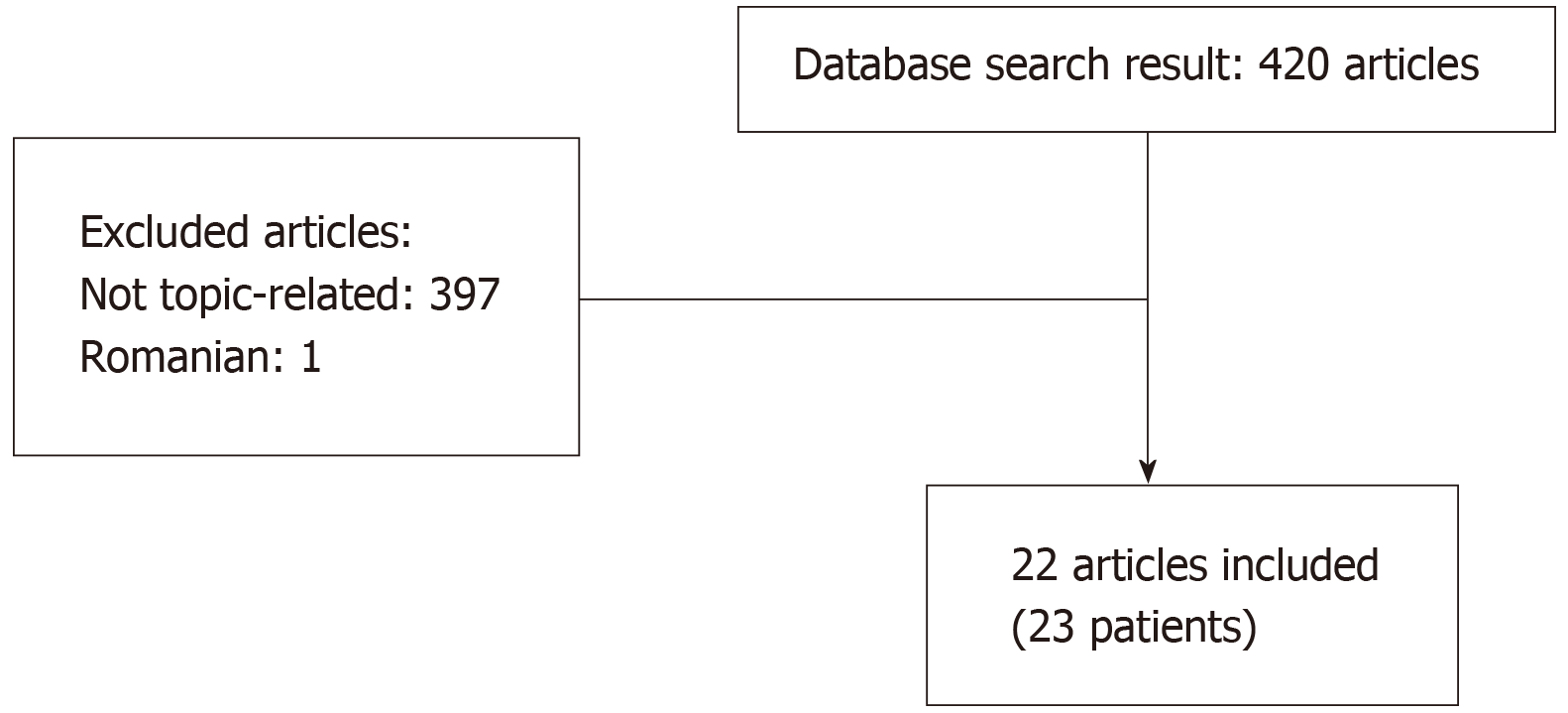

After the both initial searches, 420 articles were obtained. Only 23 (5.48%) met the search criteria, one of which were excluded because language (one in Romanian). The flowchart diagram is shown in Figure 1. We included 22 articles, including 23 patients[1,3,6,20-38].

The mean age was 56.18 years (± 15.4 SD), with a slightly male predominance (12/23). According country, 18 patients were from Southeast Asian, with 11 cases from China; while only 5 came from Western (France, Spain, Italy, United States). Right lobe was the most frequent location (12/23; 52.17%), and bilobar extension was present in 4 patients. Liu et al[28] report the coexistence of a hepatic and a pancreatic primary lesion. The median size was 15 cm (range: 2.2-27 cm). Among the symptoms, nearly 50% of patients (10/23) have no symptoms, being incidental finding during follow-up or extension study for gastric cancer in 2 of them (Table 1)

| Ref. | Yr | Age / Sex | Country | Presentation | Location | Size (cm) | Multifocal |

| Hu et al[20] | 2018 | 79/F | China | Epigastric discomfort | RL | 3.2 | No |

| Joyon et al[21] | 2018 | 56/M | France | Abdominal pain | Bilobar (Segments VII/VIII and LL) | 10 | Yes |

| 2018 | 59/F | France | Abdominal pain, weight loss | RL | 23 | No | |

| Carrillo et al[22] | 2017 | 41/M | Spain | Abdominal pain, weight loss | RL (S. V-VI) | 20 | No |

| Lok et al[23] | 2017 | 50/F | China | Abdominal pain | RL | 15 | Yes |

| Cheng et al[24] | 2016 | 63/M | China | No symptoms | RL | 15 | No |

| Nagai et al[25] | 2016 | 70/F | Japan | Follow-up gastric cancer, No symptoms | LL | 6 | No |

| Liu et al[26] | 2016 | NA | China | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang et al[27] | 2016 | 61/M | China | No symptoms | Caudate lobe | 7.3 | No |

| Liu et al[28] | 2016 | 56/F | China | No symptoms | LL + Pancreas | 2.2 | No |

| Su et al[29] | 2015 | 65/M | Taiwan | Malaise, loss of apetite, abdominal pain | LL | 12 | No |

| Bhoy et al[3] | 2014 | 41/F | India | Abdominal pain, weight loss | RL (S.VI-VI) I | 15 | Yes |

| Lin et al[30] | 2015 | 67/F | China | No symptoms | RL | 7.4 | No |

| Mao et al[31] | 2015 | 60/F | China | No symptoms | Bilobar (S I, IV, V, VIII) | 12.8 | No |

| Kim et al[32] | 2014 | 71/M | Korea | Study for early gastric cancer, No symptoms | LL | 7 | No |

| Louis et al[33] | 2014 | 55/F | India | Abdominal pain, loss of apetite | Bilobar (SII, III, VI, VIII) | 14.5 | Yes |

| Zhou et al[34] | 2014 | 56/M | China | No symptoms | RL | 10 | No |

| Li et al[35] | 2012 | 53/M | China | Abdominal discomfort | RL | 20 | No |

| Yamamoto et al[36] | 2010 | 70/M | Japan | Loss of apetite (12 years after gastric cancer) | LL | 20 | No |

| Luo et al[37] | 2009 | 17/M | China | No symptoms | RL | 5 | No |

| Ochiai et al[38] | 2009 | 30/M | Japan | Abdominal fullnes | Bilobar | 27 | No |

| De Chiara et al[1] | 2006 | 37/M | Italy | No symptoms | RL (SV) | 18 | No |

| Hu et al[6] | 2003 | 79/F | USA | Shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain | RL | 15 | No |

Regarding the diagnosis referred in Table 2, upper and lower endoscopy studies were performed in 9 patients, with no findings in 8 cases and an early gastric cancer in the other (biopsy: signet ring cell carcinoma). Biopsy of hepatic lesion was performed in 8 patients; one of them was surgical one.

| Ref. | Yr | Age / Sex | Endoscopy | Imaging | Biopsy |

| Hu et al[20] | 2018 | 79/F | Yes (no findings) | CT | No |

| Joyon et al[21] | 2018 | 56/M | NA | CT | Percutaneous |

| 2018 | 59/F | Yes (no findings) | CT | Guided | |

| Carrillo et al[22] | 2017 | 41/M | Yes (no findings) | CT / MRI | No |

| Lok et al[23] | 2017 | 50/F | Yes (no findings) | CT | No |

| Cheng et al[24] | 2016 | 63/M | NA | CT | No |

| Nagai et al[25] | 2016 | 70/F | Yes (no findings) | CT / MRI | No |

| Liu et al[26] | 2016 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang et al[27] | 2016 | 61/M | NA | CT | No |

| Liu et al[28] | 2016 | 56/F | NA | CT | Surgical |

| Su et al[29] | 2015 | 65/M | NA | CT | CT-guided |

| Bhoy et al[3] | 2014 | 41/F | NA | US/ CT | FNA |

| Lin et al[30] | 2015 | 67/F | Yes (no findings) | CT | No |

| Mao et al[31] | 2015 | 60/F | Yes (no findings) | CT / MRI | No |

| Kim et al[32] | 2014 | 71/M | Early gastric cancer | CT / MRI | No |

| Louis et al[33] | 2014 | 55/F | NA | CT | US-FNA/CT-FNA |

| Zhou et al[34] | 2014 | 56/M | Yes (no findings) | NA | No |

| Li et al[35] | 2012 | 53/M | NA | CT | US-FNAB |

| Yamamoto et al[36] | 2010 | 70/M | NA | CT | No |

| Luo et al[37] | 2009 | 17/M | NA | CT/US | US-FNA |

| Ochiai et al[38] | 2009 | 30/M | NA | CT/ MRI | No |

| De Chiara et al[1] | 2006 | 37/M | NA | CT | No |

| Hu et al[6] | 2003 | 79/F | NA | CT | No |

Regarding the treatment of the selected patients, the management was surgical in 16 cases, ranging from limited surgical excision or anatomic resection to liver transplantation or extracorporeal resection and auto transplantation.

Two patients were received local treatment, with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation. Luo et al[37] report a central hepatic lesion in a young patient. Liu et al[28] report a pancreatic primary E-GIST coexisting with another hepatic primary E-GIST, where both lesions were treated by RFA.

There were two refusals for treatment; in one case the patient refused surgery and received imatinib mesylate, and the other refused any action. In only one patient, the finding was a non-resecable hepatic lesion and the patient was treated with imatinib mesylate (Table 3).

| Ref. | Yr | Age / Sex | Treatment | Adjuvant imatinib mesylate |

| Hu et al[20] | 2018 | 79/F | Curative surgical resection | Yes |

| Joyon et al[21] | 2018 | 56/M | OLT | No |

| 2018 | 59/F | Refused surgery: imatinib mesylate | No | |

| Carrillo et al[22] | 2017 | 41/M | Segmentectomy V-VI | Yes |

| Lok et al[23] | 2017 | 50/F | Right hepatectomy | Yes |

| Cheng et al[24] | 2016 | 63/M | Right hepatectomy | Yes |

| Nagai et al[25] | 2016 | 70/F | Left lateral segmentectomy | No |

| Liu et al[26] | 2016 | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang et al[27] | 2016 | 61/M | Caudate lobe resection | No |

| Liu et al[28] | 2016 | 56/F | Microwave ablation | Yes |

| Su et al[29] | 2015 | 65/M | Irresecable: imatinib mesylate | No |

| Bhoy et al[3] | 2014 | 41/F | Right hepatectomy | Yes |

| Lin et al[30] | 2015 | 67/F | Surgical excision | Yes |

| Mao et al[31] | 2015 | 60/F | ECHRA | Yes |

| Kim et al[32] | 2014 | 71/M | Left lateral segmentectomy+excision of 1 intrabadominal nodule+total gastrectomy | NA |

| Louis et al[33] | 2014 | 55/F | Segmentectomy III and atypical resection (segments II, VI and VIII) | Yes |

| Zhou et al[34] | 2014 | 56/M | Anterior and median segmentectomy | No |

| Li et al[35] | 2012 | 53/M | Refused treatment | No |

| Yamamoto et al[36] | 2010 | 70/M | Left hepatectomy | NA |

| Luo et al[37] | 2009 | 17/M | RFA | NA |

| Ochiai et al[38] | 2009 | 30/M | L-Trisegmentectomy | Yes |

| De Chiara et al[1] | 2006 | 37/M | NA | No |

| Hu et al[6] | 2003 | 79/F | Right lobectomy | NA |

Regarding pathological, molecular and immunohistochemical findings, the most frequent cell type was spindle cells (17/23, 73.91%); molecular analysis was performed in 6 patients, with mutation in 5/6; mitotic count was ≥ 5/50 High Power Fields in 12 cases (52.17%); and CD117 was negative in only 1 patient. The risk of malignancy was classified according to Fletcher et al[2] and 17/23 (73.91%) patients had a lesion with high risk of malignancy (Table 4).

| Ref. | Yr | Age / Sex | Cell type | Molecular analysis | Mitotic count (nº / 50 HPF) | IH | Risk of malignancy |

| Hu et al[20] | 2018 | 79/F | Spindle cells | NA | NA | CD117+, CD34+ | NA |

| Joyon et al[21] | 2018 | 56/M | Spindle cells | NA | 8 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| 2018 | 59/F | Mixed (spindle and epithelioid) | 6 bp deletion in KIT exon 11 | 42 | CD117+ | High risk | |

| Carrillo et al[22] | 2017 | 41/M | Spindle cells | 9 deletion in KIT | 5 | CD 117+, CD 34- | High risk |

| Lok et al[23] | 2017 | 50/F | Spindle cells | NA | 70 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| Cheng et al[24] | 2016 | 63/M | Spindle cells | NA | >5 | CD 117 +, CD 34- | High risk |

| Nagai et al[25] | 2016 | 70/F | Spindle cells | NA | 40 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| Liu et al[26] | 2016 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang et al[27] | 2016 | 61/M | Spindle cells | NA | NA | CD117+/CD34+ | High risk |

| Liu et al[28] | 2016 | 56/F | Spindle cells | NA | 2 | CD117+ | Low risk |

| Su et al[29] | 2015 | 65/M | Spindle cells | NA | 5 | CD117+, CD 34- | High risk |

| Bhoy et al[3] | 2014 | 41/F | NA | NA | NA | CD 117+ | High risk |

| Lin et al[30] | 2015 | 67/F | Mixed (spindle and epithelioid) | Mutation in exon 11 | 8 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| Mao et al[31] | 2015 | 60/F | Spindle cells | Mutation in exon 11 | >10 | CD 117+, CD 34 - | High risk |

| Kim et al[32] | 2014 | 71/M | Spindle cells | NA | 30-32 | CD117+ | High risk |

| Louis et al[33] | 2014 | 55/F | Spindle cells | NA | 10 | CD117+ | High risk |

| Zhou et al[34] | 2014 | 56/M | Spindle cells | NA | <5 | CD117+/CD34+ | Intermediate |

| Li et al[35] | 2012 | 53/M | Spindle cells | NA | NA | CD117+, CD34+ | High risk |

| Yamamoto et al[36] | 2010 | 70/M | Epithelioid cells | mutation PDGFRA exon 12 | 1 | CD 117-/CD34+ | High risk |

| Luo et al[37] | 2009 | 17/M | Spindle cells | NA | 0 | CD117+, CD 34+ | Low risk |

| Ochiai et al[38] | 2009 | 30/M | Mixed (spindle and epithelioid) | No mutation at exon 11 | 75 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| De Chiara et al[1] | 2006 | 37/M | Spindle cells | NA | 20 | CD117+, CD 34+ | High risk |

| Hu et al[6] | 2003 | 79/F | Spindle cells | NA | 20 | CD117+, CD 34+ | Low risk |

Mean follow-up was 14 mo (range: 3-252). During the follow-up, 10 patients were disease-free (follow-up: 3-30 mo) (Table 5).

| Ref. | Yr | Outcome | Follow-up (mo) |

| Hu et al[20] | 2018 | NA | NA |

| Joyon et al[21] | 2018 | Local recurrence (12 yr) | 252 |

| 2018 | DF | 18 | |

| Carrillo et al[22] | 2017 | DF | 18 |

| Lok et al[23] | 2017 | Brain metastasis (6 mo) | 6 |

| Cheng et al[24] | 2016 | DF | 30 |

| Nagai et al[25] | 2016 | DF | 10 |

| Liu et al[26] | 2016 | NA | NA |

| Wang et al[27] | 2016 | DF | 12 |

| Liu et al[28] | 2016 | Abdominal metastasis | 17 |

| Su et al[29] | 2015 | Progression of disease (died 6 mo) | 6 |

| Bhoy et al[3] | 2014 | DF | 5 |

| Lin et al[30] | 2015 | Hepatic recurrence (24 mo) | 72 |

| Mao et al[31] | 2015 | DF | 12 |

| Kim et al[32] | 2014 | NA | NA |

| Louis et al[33] | 2014 | DF | 6 |

| Zhou et al[34] | 2014 | DF | 12 |

| Li et al[35] | 2012 | NA | NA |

| Yamamoto et al[36] | 2010 | NA | NA |

| Luo et al[37] | 2009 | DF | 3 |

| Ochiai et al[38] | 2009 | Hepatic recurrence, submucosal gastric tumor (24 mo) | 25 |

| De Chiara et al[1] | 2006 | Lung mestastasis (14 mo) | 39 |

| Hu et al[6] | 2003 | Portal lymph node mestastasis (16 mo) | 16 |

Since Hu et al[6] reported the first primary hepatic GIST in 2003, we should consider that not all tumors of the liver with GIST features are metastasis and the liver could itself be the primary GISTs location.

Primary hepatic E-GISTs are extremely uncommon compared with their alimentary counterparts; thus, E-GISTs presenting in the liver raise a difficult diagnosis, management and prognosis[22].

In this review, primary E-GISTs of the liver have a slightly male predominance and the reported cases have a Southeast Asian predominance. Regarding symptoms, almost 50% have no clinical manifestations; among symptomatic patients, the symptoms are vague compared to GISTs, which commonly present with GI bleeding, abdominal pain, a palpable mass, weight loss, nausea and vomiting[12]. Also, the size of the hepatic lesion may become larger, mean 15 cm in our review.

Once we find a tumor with GIST characteristics presenting in the liver, the main challenge is determining whether this lesion is primary or metastatic, considering the liver is the most common site of distant metastasis for malignant GIST[21,28].

All of the studies included in this systematic review are case report, lacking enough information to clarify the disease and making difficult to establish protocols. The differential diagnosis is the main challenge for primary hepatic E-GISTs, but there are no consensus guidelines. According to Joyon et al[21], the diagnosis of primary E-GIST of the liver could be considered if these conditions are present: (1) Absence of GIST in the GI tract, with endoscopic and imaging studies; and absence of connection with the muscularis propia of the GI tract; (2) Absence of any past medical history which might suggest the resection of an overlooked or misdiagnosed GIST; and (3) Absence of GI tumor diagnosed during follow-up.

Thus, every hepatic GIST should be considered metastatic until no grossly nor histologically evidence of association with the muscularis propia have been shown and the remote medical history has been carefully explored, and no primary tumor could be found on long-term follow up[39]. Not all case included in this systematic review have been described enough information to be sure that all these requirements are fulfilled. In one hand, Kim et al[32] reported a patient with two synchronous lesions, an early gastric cancer and a primary hepatic GIST. Their preoperative diagnosis was a malignant hepatic lesion with an early gastric cancer, due to presence of signet ring cells in gastric carcinoma and radiological features of liver tumor. After surgery, the pathological study showed an early gastric cancer in the lesser gastric curvature, with signet ring cell carcinoma features, and spindle cells with a positive reactivity CD117 in hepatic tumor. Nagai et al[25] reported a hepatic primary E-GIST in a patient with a previous gastric cancer 7 years earlier. Histologically, gastric cancer was a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, with lymph node involvement. When the hepatic mass was founded, upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic studies were performed, with no findings. Microscopically, the hepatic tumor was composed of spindle cells, with positive results for KIT and CD34[25]. Ochiai et al[38] reported a patient with surgical resection of a primary hepatic GIST, based on the positive immunostaining for CD34 and c-kit, and recurrent hepatic lesion and submucosal gastric tumor 2 years after first operation. After surgical removal of both hepatic and gastric lesions, both specimens showed GIST features with expression of c-kit and CD34, but the different morphological and molecular findings (gastric lesion: spindle cells and mutation in exon of c-kit; hepatic tumor: round cells and no mutation at exon 11) were enough for the authors to conclude that the hepatic GIST and gastric tumor were independent. In these patients, the different histological and immunohistochemical findings were the reason to define the hepatic lesion as a primary E-GIST. On the other hand, Liu et al[28] reported two synchronous E-GISTs. The patient presented a 5 cm-pancreatic mass and a 2 cm-hepatic lesion, with the same radiological features, and no other lesions in upper/lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations. With the diagnosis of malignant pancreatic cancer with hepatic metastases, the authors performed a surgical fine-needle aspiration and pathological findings in the hepatic and pancreatic biopsy tissues indicated that the tumors were mitotic spindle cell with CD117+[28]. The authors conclude that they are two independent lesions due to the pancreas and liver are exceptional location for primary GIST.

EGISTs have the same morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular features than conventional GISTs, including metastatic ones[12]. The criteria for the histopathological diagnosis are now firmly established; tumor cells might present a spindle or an ephiteliod appearance and show a distinctive immunophenotype characterized by the expression of KIT (CD 117)[2,28,40]. Thus, the definitive diagnosis relies on the histopathological examination[41]; however, none of the pathological features is constant and required for a definitive diagnosis, including KIT mutation, which is no detectable in almost 5% of cases[29,34]. The concerning of KIT-negative GISTs could be solved after the discovery of novel mutations of the platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha oncogene as alternative pathogenetic mechanism[39].

In the majority of cases of E-GISTs, preoperative diagnosis is not possible; therefore, patients may be easily misdiagnosed with different types of cancer and surgery is performed to made a confirm diagnosis after histological examination.

The overall management of hepatic E-GISTs is generally based on the recommendations for GI GIST. A large spectrum of therapeutic options has been proposed depending on the initial presentation and clinical context. As with GISTs, complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for E-GISTs, as long as the lesion is resectable[24,28].

A guided tumor biopsy must be considered for no-resectable tumors in order to assess the diagnosis and to offer another option for treatment such as radiofrequency, arterial embolization or chemoembolization may be considered[24,28,37]. The challenge is the risk of tumor rupture by the biopsy, well-known adverse prognostic factor in conventional GIST[42].

For E-GIST and as with GI GISTs, imatinib mesylate may be administered preoperatively in locally advanced tumor in order to minimizing the size, for adjuvant treatment for patients with a high recurrence risk or for palliative treatment in no-resectable lesions, which is similar to the guidelines for their alimentary counterparts[1,28,29,30,43]. Rediti et al[44] in 2014 and Wada et al[45] in 2012 reported the complete remission in a patient with greater omentum-mesentery E-GIST and a peritoneal E-GIST, respectively, who received only imatinib mesylate as a treatment.

On 2001, National Institutes of Health proposed a consensus classification system for defining the risk of malignant behavior, based on mitotic count and tumor size and now is widely in use, also for E-GIST[2]. Joensuu et al[46] proposed a new modified classification including primary tumor site and tumor rupture in the item for classifying the risk of GIST and the indication for adjuvant treatment.

Compared with GIST, E-GISTs have been reported to be accompanied by adverse prognostic factors, including a high proliferative index, large size and distant metastasis[15]; so E-GIST is considered to exhibit a worse prognosis, with a higher malignant potential and risk of recurrence following surgery compared with GISTs in the GI tract[2,11,15,24,26,42] Disease free-survival and disease specific-survival of hepatic GISTs are significantly worse than those of gastric and small intestine GISTs and the location is an independent prognostic factor[26]. There is a trend that E-GIST is an aggressive group with worse outcome. In this review, which includes only case reports, 10/23 patients are DF with a follow-up between 3 and 30 mo, and 8/23 patients had progression of E-GIST or metastasis, with not available data in 5 patients.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of E-GIST must be considered in a liver mass. Rendering an accurate diagnosis is a challenge, as well as the confirmation of their primary or metastatic nature. The optimal treatment is surgery and imatinib mesylate has a role as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced tumors, adjuvant treatment if the lesion has a high risk for recurrence, and palliative treatment if there is distant metastasis. Literature on hepatic E-GIST is scarce and further studies such as multicentric databases are needed to clarify diagnosis and treatment.

A minor subset of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) can also arise outside the gastrointestinal tract, which is known as an extra-GIST (E-GIST).

Primary GIST of the liver is an exceptional location and this study aimed to characterize epidemiological, clinical and pathological features and options of treatments.

Our aim is to characterize epidemiological, clinical and pathological features and options of treatments.

We perform a system review including all patients with hepatic GISTs.

This review shows that right hepatic lobe was the most frequent location, the median size was higher, there was a Southeast Asian predominance, and nearly 50% of patients have no symptoms. The most frequent treatment was surgery and more than 70% of patients had a lesion with high risk of malignancy.

Literature on hepatic EGIST is scarce and further studies such as multicentric databases are needed to clarify diagnosis and treatment.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Misiakos EP, Milone M S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | De Chiara A, De Rosa V, Lastoria S, Franco R, Botti G, Iaffaioli VR, Apice G. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver with lung metastases successfully treated with STI-571 (imatinib mesylate). Front Biosci. 2006;11:498-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O'Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP, Shmookler B, Sobin LH, Weiss SW. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2231] [Cited by in RCA: 2149] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Bhoy T, Lalwani S, Mistry J, Varma V, Kumaran V, Nundy S, Mehta N. Primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Trop Gastroenterol. 2014;35:252-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sheppard K, Kinross KM, Solomon B, Pearson RB, Phillips WA. Targeting PI3 kinase/AKT/mTOR signaling in cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 2012;17:69-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Feng F, Tian Y, Liu Z, Xu G, Liu S, Guo M, Lian X, Fan D, Zhang H. Clinicopathologic Features and Clinical Outcomes of Esophageal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: Evaluation of a Pooled Case Series. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 6. | Hu X, Forster J, Damjanov I. Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1606-1608. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Vanel D, Albiter M, Shapeero L, Le Cesne A, Bonvalot S, Le Pechoux C, Terrier P, Petrow P, Caillet H, Dromain C. Role of computed tomography in the follow-up of hepatic and peritoneal metastases of GIST under imatinib mesylate treatment: a prospective study of 54 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao X, Yue C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:189-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miettinen M, Majidi M, Lasota J. Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 5:S39-S51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:70-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 72.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 12. | Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, Weiss SW. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:577-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Min KW, Leabu M. Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): facts, speculations, and myths. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:995-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huizinga JD, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. About the presence of interstitial cells of Cajal outside the musculature of the gastrointestinal tract. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yi JH, Sim J, Park BB, Lee YY, Jung WS, Jang HJ, Ha TK, Paik SS. The primary extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of pleura: a case report and a literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:1269-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors--definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1185] [Cited by in RCA: 1177] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1213-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Manterola C, Vial M, Pineda V, Sanhueza A. Systematic review of literature with different types of designs. Int J Morphol. 2009;27:1179-1186. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Laupacis A, Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1992;102:305S-311S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hu HJ, Fu YY, Li FY. Primary Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor of the Liver. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Joyon N, Dumortier J, Aline-Fardin A, Caramella C, Valette PJ, Blay JY, Scoazec JY, Dartigues P. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) presenting in the liver: Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic issues. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:e23-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Carrillo Colmenero AM, Serradilla Martín M, Redondo Olmedilla MD, Ramos Pleguezuelos FM, López Leiva P. Giant primary extra gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Cir Esp. 2017;95:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lok HT, Chong CN, Chan AW, Fong KW, Cheung YS, Wong J, Lee KF, Lai PB. Primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor presented with rupture. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2017;6:65-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cheng X, Chen D, Chen W, Sheng Q. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2772-2776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nagai T, Ueda K, Hakoda H, Okata S, Nakata S, Taira T, Aoki S, Mishima H, Sako A, Maruyama T, Okumura M. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu Z, Tian Y, Liu S, Xu G, Guo M, Lian X, Fan D, Zhang H, Feng F. Clinicopathological feature and prognosis of primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2268-2275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhong Y, Ji B. Malignant extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3929-3932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu L, Zhu Y, Wang D, Yang C, Zhang QI, Li X, Bai Y. Coexisting and possible primary extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the pancreas and liver: A single case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3303-3307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Su YY, Chiang NJ, Wu CC, Chen LT. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver in an anorectal melanoma survivor: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2366-2370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lin XK, Zhang Q, Yang WL, Shou CH, Liu XS, Sun JY, Yu JR. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver treated with sequential therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2573-2576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mao L, Chen J, Liu Z, Liu CJ, Tang M, Qiu YD. Extracorporeal hepatic resection and autotransplantation for primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:174-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim HO, Kim JE, Bae KS, Choi BH, Jeong CY, Lee JS. Imaging findings of primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Jpn J Radiol. 2014;32:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Louis AR, Singh S, Gupta SK, Sharma A. Primary GIST of the liver masquerading as primary intra-abdominal tumour: a rare extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumour (EGIST) of the liver. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;45:392-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhou B, Zhang M, Yan S, Zheng S. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:1142-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Li ZY, Liang QL, Chen GQ, Zhou Y, Liu QL. Extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver diagnosed by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yamamoto H, Miyamoto Y, Nishihara Y, Kojima A, Imamura M, Kishikawa K, Takase Y, Ario K, Oda Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver with PDGFRA gene mutation. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:605-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Luo XL, Liu D, Yang JJ, Zheng MW, Zhang J, Zhou XD. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3704-3707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ochiai T, Sonoyama T, Kikuchi S, Ikoma H, Kubota T, Nakanishi M, Ichikawa D, Kikuchi S, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Sakakura C, Kokuba Y, Taniguchi H, Otsuji E. Primary large gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:633-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Agaimy A, Wünsch PH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a regular origin in the muscularis propria, but an extremely diverse gross presentation. A review of 200 cases to critically re-evaluate the concept of so-called extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:322-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:399-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 41. | Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Barusevicius A, Miettinen M. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:728-734. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, Nilsson B, Cirilli C, Braconi C, Bordoni A, Magnusson MK, Linke Z, Sufliarsky J, Federico M, Jonasson JG, Dei Tos AP, Rutkowski P. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Casper ES, Conrad EU, DeLaney TF, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM, Mayerson J, McGarry SV, Meyer C, O'Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Schupak KD, Schwartz HS, Van Tine BA, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Sundar H. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:853-862. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Rediti M, Pellegrini E, Molinara E, Cerullo C, Fonte C, Lunghi A, Iori A, Neri B. Complete pathological response in advanced extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor after imatinib mesylate therapy: a case report. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:905-907. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Wada Y, Ogata H, Misawa S, Shimada A, Kinugasa E. A hemodialysis patient with primary extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumor: favorable outcome with imatinib mesylate. Intern Med. 2012;51:1561-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |