Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.101187

Revised: October 26, 2024

Accepted: December 12, 2024

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 188 Days and 15.7 Hours

The global incidence of cirrhosis and luminal gastrointestinal cancers are increasing. It is unknown if cirrhosis itself is a predisposing factor for luminal gastrointestinal cancer. Such an association would have significant clinical implications, particularly for cancer screening prior to liver transplantation.

To investigate the incidence of luminal gastrointestinal cancers in patients with underlying cirrhosis.

An electronic search was conducted to study the incidence of luminal gastroin

We identified 5054 articles; 4 studies were selected for data extraction. The overall incidence of all cancers was significantly higher in patients with cirrhosis, with an SIR of 2.79 (95%CI: 2.18–3.57). When stratified by cirrhosis etiology, the incidence of luminal cancers remained significantly elevated for alcohol (SIR = 3.13, 95%CI: 2.24–4.39), Primary Biliary Cholangitis (SIR = 1.40, 95%CI: 1.10–1.79), and unspecified cirrhosis (SIR = 3.52, 95%CI: 1.87–6.65).

The incidence of luminal gastrointestinal cancer is increased amongst patients with cirrhosis. Oral cavity, pharyngeal and esophageal cancer had increased incidence across all cirrhosis etiologies compared to gastric and colorectal cancer. Therefore, increased screening of luminal cancers, and in particular these upper luminal tract subtypes, should be considered in this population.

Core Tip: Very limited data remains studying the association between luminal gastrointestinal cancers and cirrhosis. We showed that overall incidence of gastrointestinal cancers is higher in patients with cirrhosis. Alcohol related cirrhosis had the highest incidence of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Primary biliary cirrhosis did not demonstrate higher incidence of cancer sites.

- Citation: Jogendran M, Zhu K, Jogendran R, Sabrie N, Hussaini T, Yoshida EM, Chahal D. Incidence of luminal gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(1): 101187

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i1/101187.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.101187

The global incidence of cirrhosis is rising, paralleled by a growing number of patients with gastrointestinal cancers[1,2]. Notably, patients with gastrointestinal cancer may also have underlying cirrhosis[3,4]. The presence of cirrhosis complicates the management of patients with malignancy, potentially limiting both surgical and chemotherapeutic options due to concerns regarding increased peri-operative hepatic decompensation and hepatotoxicity[5,6]. Importantly, the presence of malignancy would detrimentally impact post liver transplant outcomes, and if detected during transplant assessment, may exclude patients from liver transplantation altogether[7].

While it is widely acknowledged that liver cirrhosis is associated with heightened susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), there are limited data regarding the incidence of extrahepatic cancers in cirrhosis. As such, we have herein conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the incidence of luminal gastrointestinal cancers in patients with underlying cirrhosis.

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses statement. An electronic search of EMBASE (1974–present), MEDLINE (1946–present), EBM Reviews–Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1946–present) and EBM Reviews–Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005–present) was conducted to study the incidence of gastrointestinal cancer in cirrhosis. The MeSH searched were “cirrhosis” AND “esophageal cancer” OR “colon cancer” OR “gastric cancer” OR “small bowel cancer” OR “rectal cancer” OR “oropharyngeal cancer”. From these initially selected articles, the references were analyzed to identify additional relevant articles. Please refer to our appendix documents for full details regarding our search strategy.

Three investigators (Jogendran M, Jogendran R, Sabrie N) conducted the initial screen by independently reviewing study titles and abstracts to identify full text studies examining the incidence of luminal gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cirrhosis. Only studies in English were used in this systematic review. Those that met the criteria were reviewed in full. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through consensus.

Two investigators (Jogendran M, Jogendran R) extracted and tabulated the following data: (1) Study characteristics (title, author, location, type of study, region, study period); (2) Cause of cirrhosis; (3) Demographics (gender and age); and (4) Cancer characteristics [number of cancers, standardized incidence ratio (SIR), and mean follow-up years]. The primary outcome assessed was the incidence of gastrointestinal cancers.

Study-specific SIRs along with their corresponding 95%CI for both overall cancer incidence and luminal cancer incidence were synthesized using a random-effects model. We employed the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model due to expected clinical and methodological diversity among the included studies. The relative weight of each study was determined through generic inverse-variance weighting. However, due to the limited number of included studies, we did not generate a funnel plot to assess publication bias. For a subgroup analysis of the association between cirrhosis and luminal malignancy, we stratified patients based on their cirrhosis etiology, which included alcohol related liver disease, PBC, or unspecified causes. Furthermore, luminal malignancy was further sub-grouped, where reported, into oral cavity and pharynx, esophageal, stomach, and colorectal cancer.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q statistic and I2 statistic, where P < 0.10 and I2 > 50% were considered significant indicators of heterogeneity. The significance level for all other statistical tests was set at P < 0.05. RevMan version 5.4 (Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for all statistical analyses

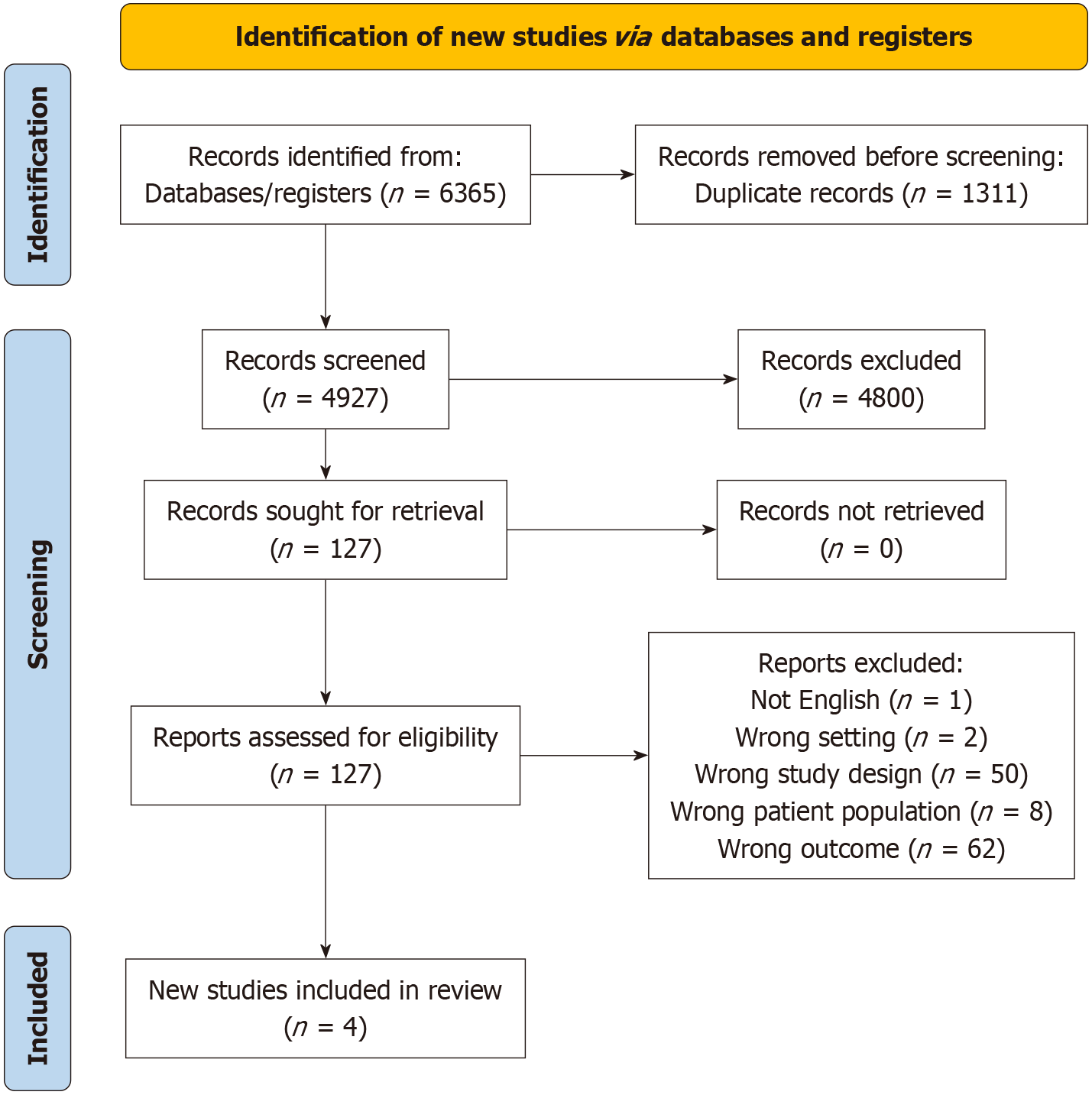

The search strategy identified 5054 articles after duplicates were removed, 4927 were excluded after examining the title and abstract. Full text review of 127 papers was then undertaken. Of these, 4 studies were selected for data extraction. Studies were excluded for various reasons, including being reviews, case reports, wrong outcomes, wrong patient population and not being in the English language (Figure 1). All studies were retrospective studies and conducted in European countries[8-11].

The study characteristics of the included summaries are outlined in Table 1. A total of 23877 patients were included, comprising 16722 patients with alcohol related cirrhosis, 744 with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) cirrhosis, 1690 with chronic hepatitis cirrhosis, and 4721 with unspecified cirrhosis. The studies were conducted in Europe, including Finland, Sweden, England, and Denmark. The study durations ranged from 11 to 36 years, with a mean of 16.6 years.

| Ref. | Study years | Country | Patient population | Sex, female | Age, mean years | Mean follow-up (years) |

| Sahlman et al[8] | 1996-2012 | Finland | Alcohol related cirrhosis: 7746 (65). Alcoholic hepatitis: 4127 (35) | 3077 (26) | N/A | 2.9 |

| Kalaitzakis et al[9] | 1994-2005 | Sweden | Alcohol related cirrhosis: 492 (48). Non-specified cirrhosis: 527 (52) | 323 (32) | 52 (12) | 3.3 |

| Goldacre et al[10] | 1963-1999 | England | Alcohol related cirrhosis: 1319 PBC; cirrhosis: 424; non-specified cirrhosis: 1764. Alcohol related cirrhosis: 7165 (62). PBC cirrhosis: 320 (3). Chronic hepatitis cirrhosis: 1690 (14) | 1603 (46) | N/A | N/A |

| Sorensen et al[11] | 1977-1989 | Denmark | Non-specified cirrhosis: 2430 (21) | 4547 (39) | N/A | 6.4 |

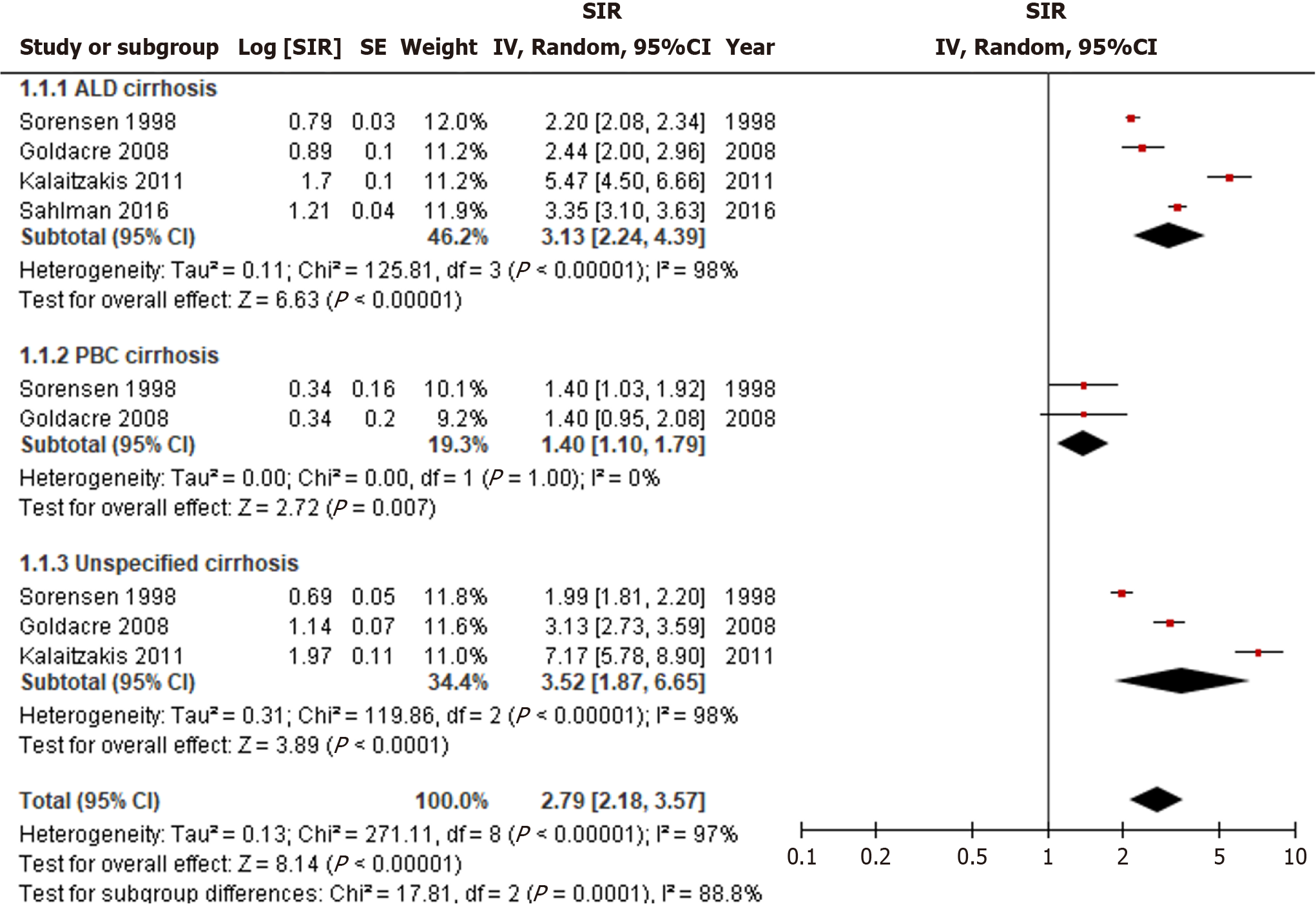

The overall incidence of all cancers was significantly higher in patients with cirrhosis, with a significant SIR of 2.79 (95%CI: 2.18-3.57, I2 = 97%) (Figure 2). When stratified by cirrhosis etiology, the incidence of all cancers remained significantly elevated for alcohol related (SIR = 3.13, 95%CI: 2.24-4.39, I2 = 98%), PBC (SIR = 1.40, 95%CI: 1.10-1.79, I2 = 0%), and unspecified cirrhosis (SIR = 3.52, 95%CI: 1.87-6.65, I2 = 98%). Unspecified cirrhosis had the greatest overall cancer risk followed by alcohol related cirrhosis, and PBC cirrhosis (P < 0.01). High heterogeneity was observed and persisted even after conducting subgroup analyses based on cirrhosis etiology.

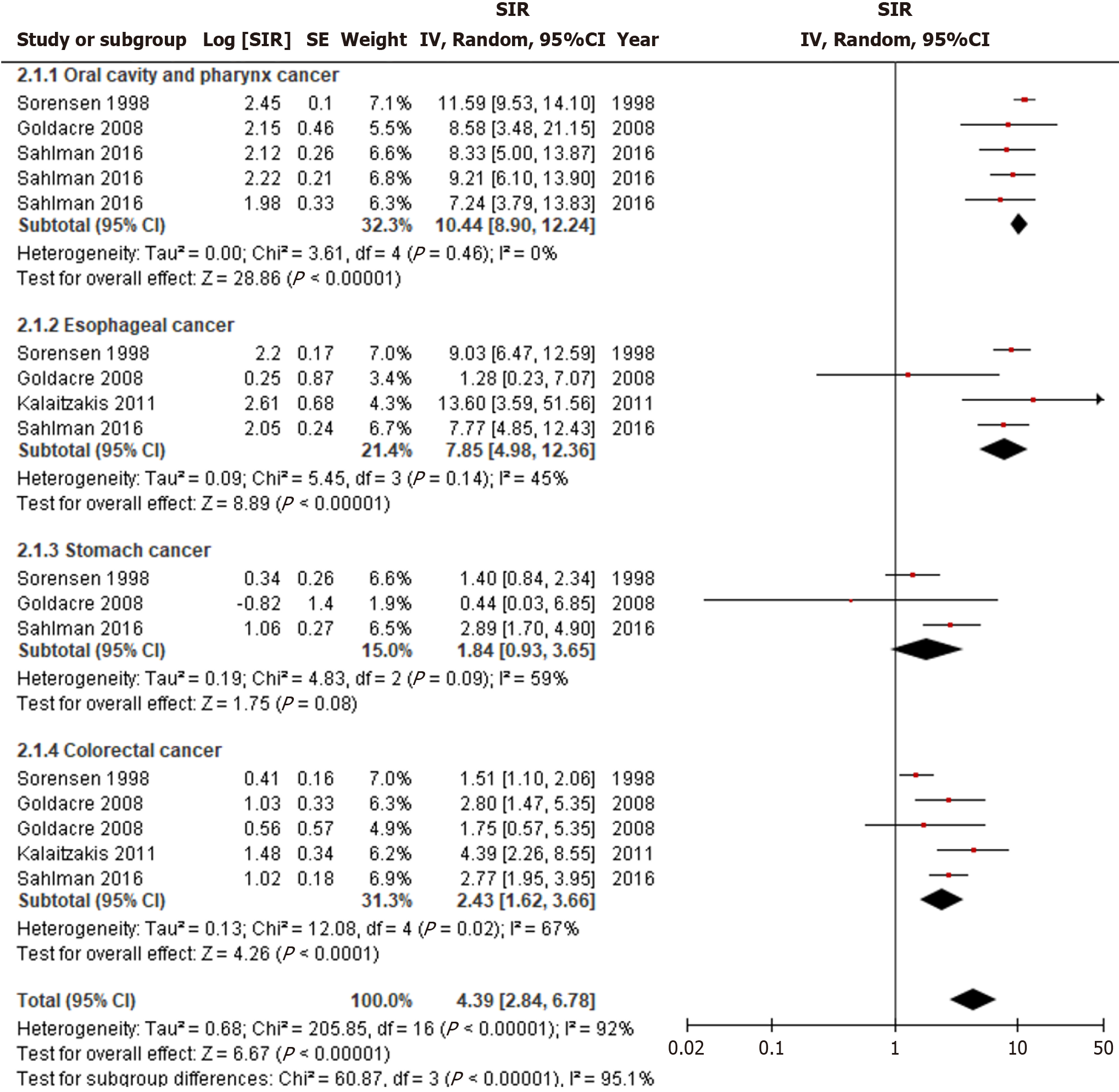

Alcohol related cirrhosis was significantly associated with an increased incidence of luminal cancers (SIR = 4.39, 95%CI: 2.84-6.78, I2 = 92%) (Figure 3). Specifically, the highest incidence was observed for oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer (SIR = 10.44, 95%CI: 8.90-12.24, I2 = 0%), followed by esophageal cancer (SIR = 7.85, 95%CI: 4.98-12.36, I2 = 45%), and colorectal cancer (SIR = 2.43, 95%CI: 1.62-3.66, I2 = 67%) (P < 0.01). The incidence of gastric cancer was not significantly associated with alcohol related cirrhosis (SIR = 1.84, 95%CI: 0.93-3.65, I2 = 59%). Heterogeneity was less pronounced when subgrouped according to the etiology of luminal cancer, but significant differences remained for the stomach and colorectal cancer subgroups.

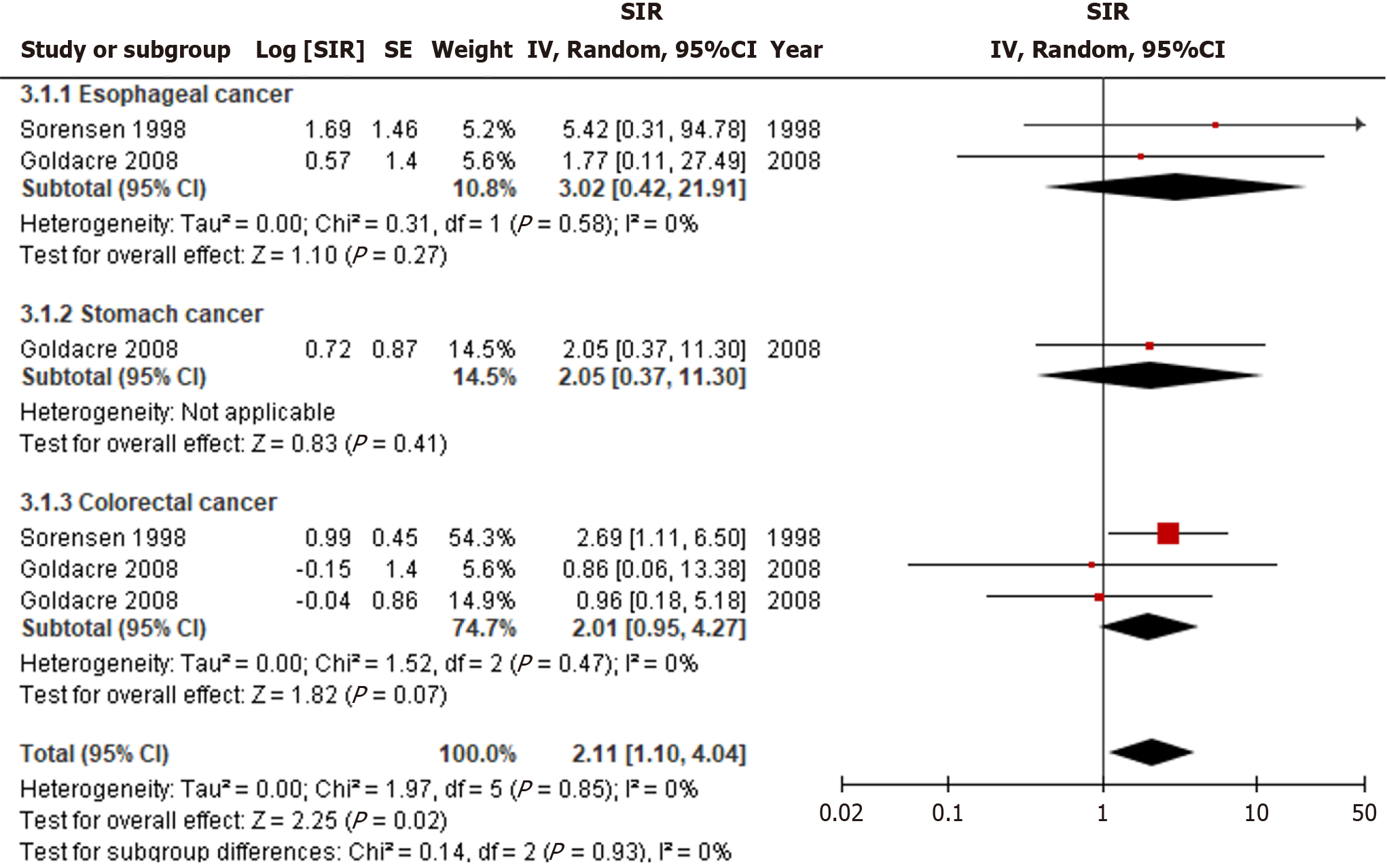

PBC cirrhosis is significantly associated with an increased incidence of luminal cancers (SIR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.10-4.04, I2 = 0%) (Figure 4). However, subgroup analysis did not reveal a significant association with the incidence of any subgroups, including esophageal, stomach, or colorectal cancer. There was no significant statistical heterogeneity among the studies.

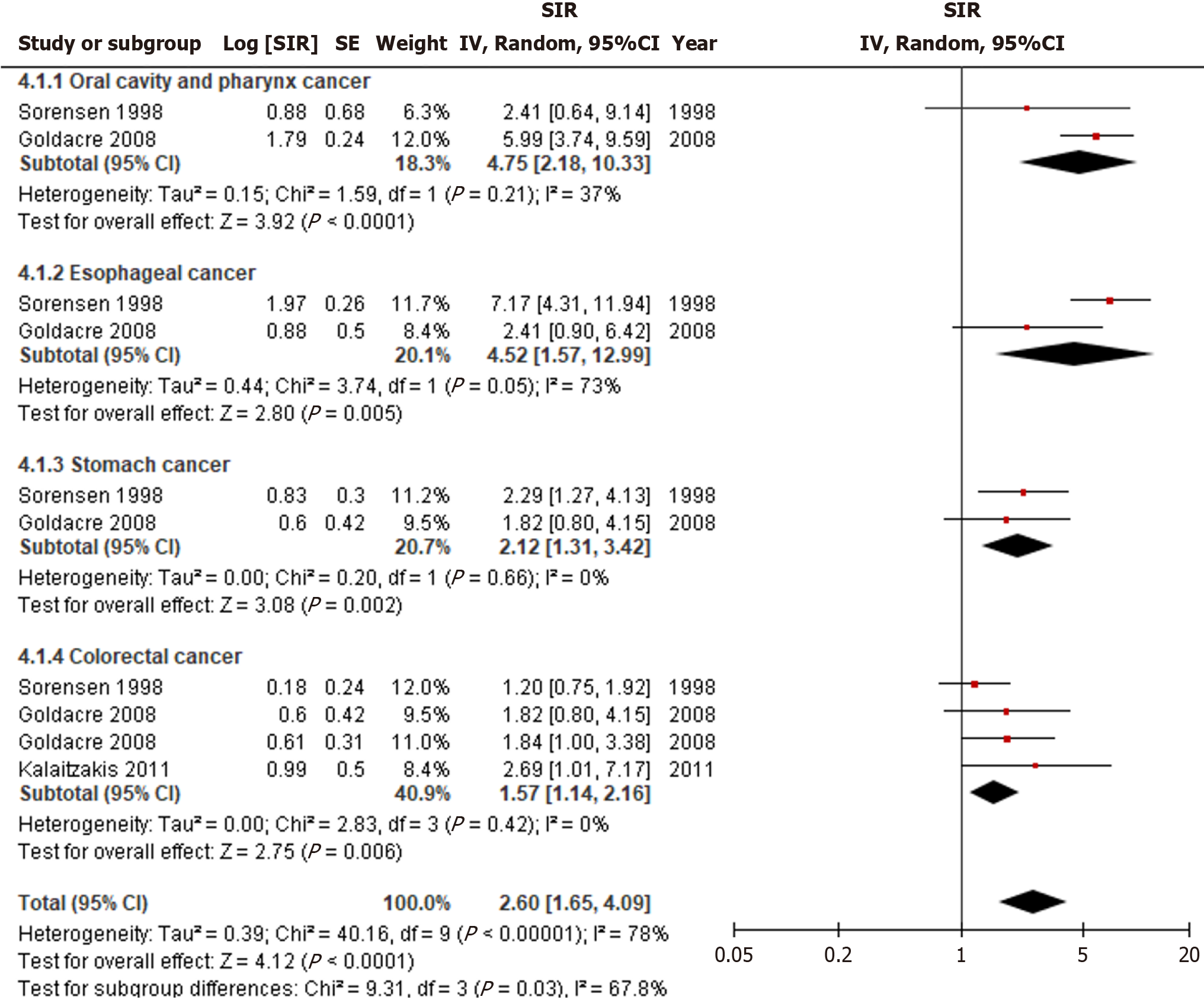

Unspecified cirrhosis was significantly linked to an increased incidence of luminal cancers (SIR = 2.60, 95%CI: 1.65-4.09, I2 = 78%) (Figure 5). Risk of oral cavity and pharynx cancers (SIR = 4.75, 95%CI: 2.18-10.33, I2 = 37%) were greatest, followed by esophageal (SIR = 4.52, 95%CI: 1.57-2.99, I2 = 73%), stomach (SIR = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.31-3.42, I2 = 0%), and colorectal cancer (SIR = 1.57, 95%CI: 1.14-2.16, I2 = 0%) (P = 0.03). When stratified by luminal cancer subgroups, only esophageal cancer exhibited statistical heterogeneity, while the others did not.

The association between cirrhosis and HCC is well-established[12,13]. Patients diagnosed with cirrhosis undergo routine HCC screening due to increased cancer risk[14]. However, screening remains limited for luminal gastrointestinal cancers in this patient population[15]. Given the growing literature, it is crucial to systematically evaluate the possibility of increased risk of developing luminal gastrointestinal cancers in cirrhosis patients, considering both the etiology of cirrhosis and the specific sites of gastrointestinal cancer. Our meta-analysis incorporated four studies and revealed that the overall incidence of all luminal gastrointestinal cancers was higher in patients with cirrhosis. Notably, alcohol related cirrhosis exhibited the highest incidence of oral and pharyngeal cancer, followed by esophageal and colorectal cancer. On the other hand, PBC did not demonstrate a significantly higher incidence within the specified cancer site subgroups. However, our study had high heterogeneity in our analysis which may limit the validity of these findings.

Prior studies have demonstrated similar findings to our review. For instance, Zullo et al[16] concluded a 2.6-fold increase in the prevalence of gastric cancer among individuals with cirrhosis. Additionally, a study led by Pan et al[17], encompassing 1391165 admissions for gastrointestinal malignancies, found that 81.7% of cirrhosis cases were associated with HCC, 8.1% with pancreatic cancer, and 5.7% with colorectal cancer. Patients with cirrhosis also exhibited a higher mortality risk, possibly attributed to limited treatment options due to underlying cirrhosis[17]. The increase in cirrhosis and luminal gastrointestinal cancers may be related to shared risk factors between certain gastrointestinal cancers and cirrhosis, such as alcohol and tobacco use. It is also hypothesized that gastric erosive ulcers, congestive gastropathy, zinc deficiency, and alterations in gastrointestinal microbiota, which are all features of cirrhosis, can be associated with malignancy[3].

Despite employing a systematic review and meta-analysis methodology there remain inherent limitations to this study. Our meta-analysis primarily included a diverse range of patients from various study designs, which could potentially impact the interpretation of our results. Moreover, our study primarily focused on a European population, and the findings may not be directly applicable to other regions. Furthermore, the underlying causes of cirrhosis varied, encompassing alcohol related, PBC, and unspecified aetiologies. This lack of specificity in the unspecified group presents a challenge, as it makes it difficult to discern the exact aetiologies within this category. There may be cases that overlap with alcohol related and PBC-related cirrhosis. Ideally, future retrospective or prospective studies should incorporate standardized data on covariates. Finally, all studies included were retrospective in nature. Prospective cohort studies evaluating the incidence of luminal gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with cirrhosis may be of use in the future.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrated a significant increase in luminal gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cirrhosis in comparison to the general population. As such, we believe that screening for luminal gastrointestinal cancers may be needed for patients with cirrhosis. Screening for oropharyngeal malignancy may be of importance during assessment for liver transplantation, particularly in patients with alcohol related disease. Comprehensive, long-term studies will be necessary for potential redevelopment of screening guidelines including, esophageal and oropharyngeal screening.

| 1. | Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL, Arrese M, Bugianesi E, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:388-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 175.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64637] [Article Influence: 16159.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 3. | Jeng KS, Chang CF, Sheen IS, Jeng CJ, Wang CH. Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer and Liver Cirrhosis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pinter M, Trauner M, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Sieghart W. Cancer and liver cirrhosis: implications on prognosis and management. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kaltenbach MG, Mahmud N. Assessing the risk of surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Friedman LS. Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2010;121:192-204; discussion 205. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Benkö T, Hoyer DP, Saner FH, Treckmann JW, Paul A, Radunz S. Liver Transplantation From Donors With a History of Malignancy: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant Direct. 2017;3:e224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sahlman P, Nissinen M, Pukkala E, Färkkilä M. Incidence, survival and cause-specific mortality in alcoholic liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:961-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kalaitzakis E, Gunnarsdottir SA, Josefsson A, Björnsson E. Increased risk for malignant neoplasms among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goldacre MJ, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Seagroatt V, Collier J. Liver cirrhosis, other liver diseases, pancreatitis and subsequent cancer: record linkage study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, Thulstrup AM, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, Trichopoulos D, Vilstrup H, Olsen J. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4432] [Cited by in RCA: 3881] [Article Influence: 970.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in RCA: 1793] [Article Influence: 85.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Demirtas CO, Ozdogan OC. Surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: Current knowledge and future directions. Hepatol Forum. 2020;1:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xiang Z, Li Y, Zhu C, Hong T, He X, Zhu H, Jiang D. Gastrointestinal Cancers and Liver Cirrhosis: Implications on Treatments and Prognosis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:766069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zullo A, Romiti A, Tomao S, Hassan C, Rinaldi V, Giustini M, Morini S, Taggi F. Gastric cancer prevalence in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pan C, Cuartas Mesa MC. Impact of cirrhosis on mortality in gastrointestinal malignancies: A retrospective study from nationwide database. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:e16324-e16324. [DOI] [Full Text] |