Published online Mar 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i7.1668

Peer-review started: September 17, 2020

First decision: October 27, 2020

Revised: November 3, 2020

Accepted: November 13, 2020

Article in press: November 13, 2020

Published online: March 6, 2021

Processing time: 164 Days and 12.5 Hours

To summarize the imaging, morphological and biological characteristics of sarcomatoid carcinoma (SC) of the prostate with bladder invasion not long after castration.

Our two cases were initially diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the prostate due to dysuria. However, prostate SC was diagnosed after transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and castration after only 5 and 10 mo, respectively. Distinctive liver-like tissues appeared in the second TURP procedure in case 1, while a white, fish flesh-like, narrow pedicled soft globe protruded from the prostate to the bladder in case 2.

The sarcomatoid component of SC may arise from one of the specific groups of cancer cells that are resistant to hormonal therapy. Morphological characteristics of SCs can present as “red hepatization” and “fish flesh”. SCs grow rapidly and have a poor prognosis, and thus, extensive TURP plus radiation may be the treatment of choice.

Core Tip: The sarcomatoid component of prostate sarcomatoid carcinomas (SCs) may arise from one of the specific groups of cancer cells that are resistant to hormonal therapy. Morphological characteristics of the SCs can present as “red hepatization” and “fish flesh”. The SCs grow rapidly and have a poor prognosis, and thus, extensive transurethral resection of the prostate plus radiation may be the treatment of choice. Sarcomatoid components may be another pathway of lineage plasticity during prostate adenocarcinoma progression and therapy resistance.

- Citation: Wei W, Li QG, Long X, Hu GH, He HJ, Huang YB, Yi XL. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate with bladder invasion shortly after androgen deprivation: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(7): 1668-1675

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i7/1668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i7.1668

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (SC) of the prostate accounts for less than 1% of all prostate malignancies, and may arise from both mesenchymal and epithelial components of the prostate[1,2].

Most SCs reported in the literature are single cases or small series, while only two studies examining more than 40 cases have been published. Both of these studies were from Johns Hopkins University, and the interval between the two studies was close to 10 years[1,3,4].

Endocrine therapy is one of the most important treatments for prostate cancer. However, androgen ablation and traditional chemotherapy cannot alter the natural course of SCs. It has been reported that there were no durable responses, although different chemotherapy regimens were used[3].

SCs are aggressive and have a poor prognosis. The median overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced SCs is 7.1 to 9 mo[1]. Among the cases with advanced disease, up to 60% are local prostate SCs with bladder invasion. Once the tumor invades the bladder, the OS is similar to that of metastatic SCs. However, their biological characteristics have rarely been well-reported previously. We report two cases of prostate SC with bladder invasion not long after transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and androgen deprivation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first detailed report of the morphological characteristics of SC.

An 80-year-old male patient complained of worsening dysuria, hematuria and pain on urination for 7 mo. A 72-year-old male patient complained of worsening dysuria and hematuria for 5 mo.

Case 1: A biopsy before admission indicated adenocarcinoma of the prostate. He received several cycles of catheterization due to acute urinary retention. Computed tomography (CT) showed local prostate nodules, which did not rule out prostatic hyperplasia. Signs of metastasis to the right eighth posterior ribs, pelvic and sacral bone were indicated by emission computed tomography (ECT).

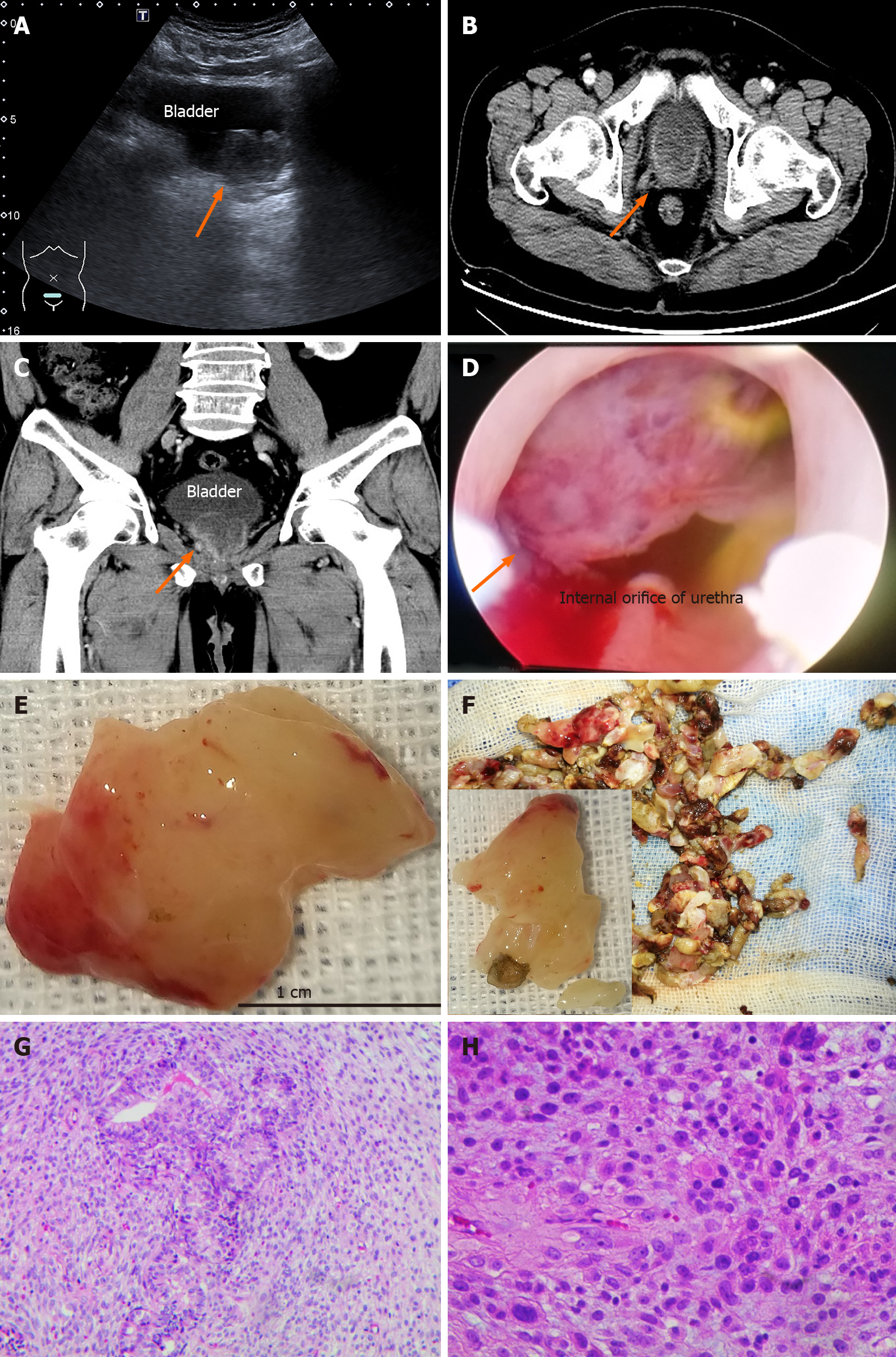

Case 2: A TURP was performed to relieve urinary retention 5 mo ago. Orchiectomy was then performed as prostate adenocarcinoma was diagnosed. Unfortunately, the patient experienced almost constant hematuria after surgery. Bladder cancer was found one week before attending our hospital due to dysuria and urinary retention (Figure 1A).

Case 1: He received several cycles of catheterization due to acute urinary retention.

Case 2: A TURP was performed to relieve urinary retention 5 mo ago. Orchiectomy was then performed as prostate adenocarcinoma was diagnosed.

No relevant personal or family history.

Acute urinary retention was observed in both patients.

CT showed local prostate nodules, which did not rule out prostatic hyperplasia. Signs of metastasis to the right eighth posterior ribs, pelvic and sacral bone were indicated by ECT.

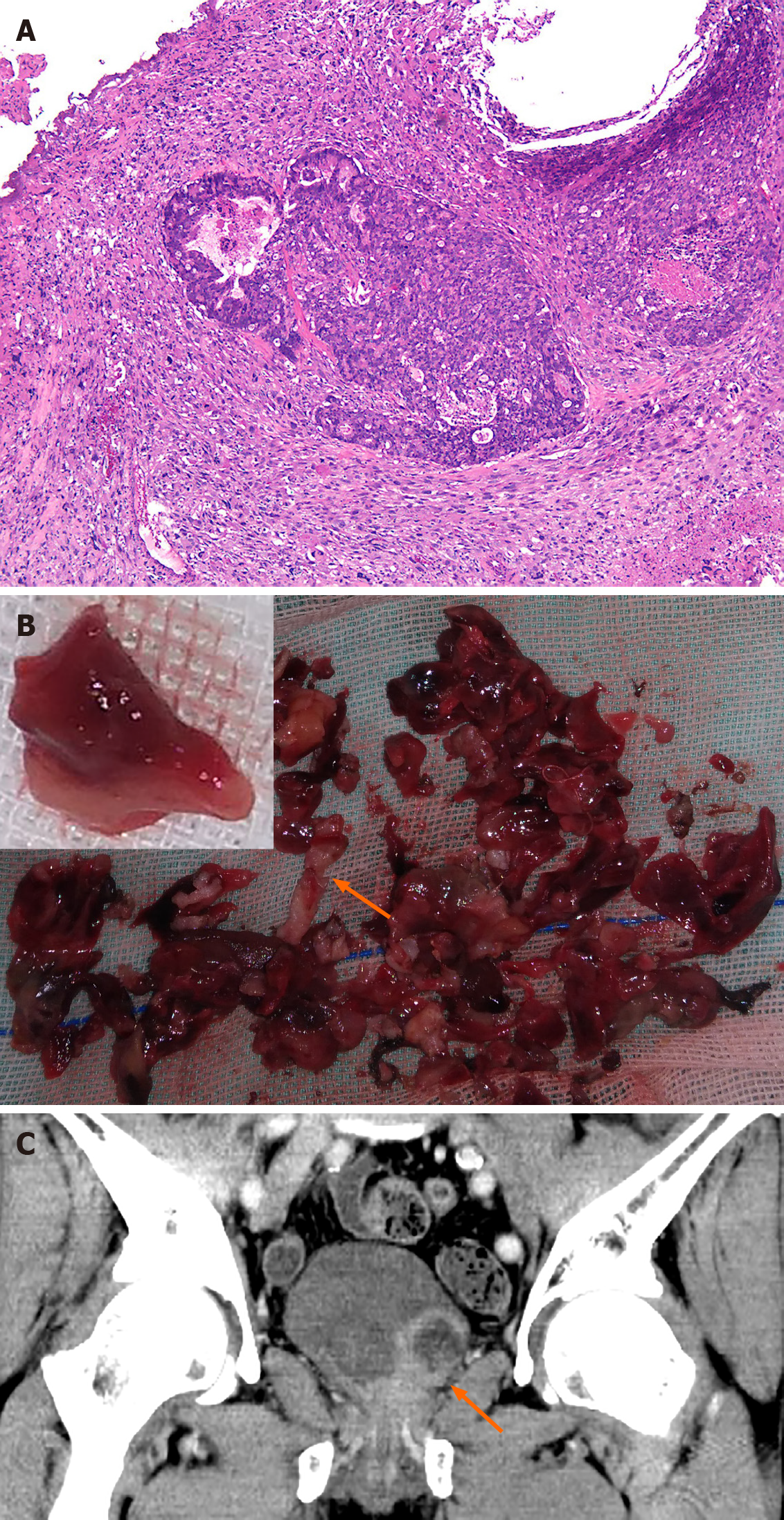

Case 1: TURP and bilateral orchiectomy were performed. The histopathology specimen showed Gleason scores of 3 + 4 = 7, prostate adenocarcinoma involving > 90% of the prostate with nerve invasion, but no vascular tumor thrombus (Table 1). Androgen resistant treatment was given after surgery. The histopathology specimen showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma with extensive necrosis. The majority of the tumor tissue was undifferentiated sarcoma with prostate adenocarcinoma involving less than 2% of the prostate (Figure 2A). The tumor cells were spindle-shaped, diffuse, and distributed with significant atypia and pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and tumor giant cells were visible.

| Test | Case 1 | Case 2 | Normal reference range | ||

| First TURP | Second TURP | First TURP | Second TURP | ||

| Blood | |||||

| TPSA | 37.12 | 7.19 | < 4 | 0.01 | 0-4 ng/mL |

| FPSA | 7.7 | 1.17 | < 1.3 | 0 | 0-1.3 ng/mL |

| CRP | 8.3 | 3.4 | 8.88 | ND | 0-10 mg/L |

| hs-CRP | 3.21 | 1.08 | < 3 | ND | 0-3 mg/L |

| IgG | 12.82 | 12.92 | ND | 8-16 g/L | |

| Alexin C3 | 1.14 | 1.2 | 1.04 | 0.9-1.5 g/L | |

| Alexin C4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.29 | 0.2-0.4 g/L | |

| Creatinine | 76 | 76 | < 123 | 83 | 53-123 μmol/L |

| Platelets | 193.92 | 231 | 283 | 100-300 × 109/L | |

| ALP | 111 | 72 | 88 | 25-135 g/L | |

| LDH | 235 | 214 | 126 | 114-240 g/L | |

| SF | 257 | 299 | 622 | 20-300 μg/L | |

| Albumin globulin ratio | 0.68 | 1.26 | 1.09 | 1-2.5 | |

| White blood cell count | 5.03 | 5.41 | < 9.15 | 8.78 | 3.97-9.15 × 109/L |

| Percent neutrophils | 66.40% | 72.20% | 59.90% | 45-77% | |

| Percent lymphocytes | 21.50% | 16.20% | 29.90% | 20%-40% | |

| Hemoglobin | 115 | 106 | 119 | 131-172 g/L | |

| MCV | 91.35 | 90 | 87.3 | 86-100 fl | |

| MCH | 29.31 | 28.9 | 28.1 | 26-31 pg | |

| D-Dimer | 11.74 | 1.83 | 0.5 | 0-1 mg/L | |

| FSH | 13.52 | ND | ND | 53.5 | 1.5-12.5 mIU/mL |

| LH | 10.18 | ND | ND | 27 | 1.7-8.6 mIU/mL |

| Testosterone | 7.2 | ND | ND | 0.23 | 2.8-8 ng/mL |

| Urine | |||||

| RBC | > 250 | 150 | 174 | 120 | 0-5 μL |

| WBC | > 400 | 5 μL | 33.6 | 30 | 0-5 μL |

| CEA | 5.7 | 5.23 | ≤ 5 ng/mL | ||

| IgM | 2.72 | 0.5-2.2 g/L | |||

| IgG | 12.82 | 12.92 | 14.86 | 8-16 g/L | |

| C1q | 269.87 | 159-233 mg/L | |||

| Immunohistochemistry | |||||

| Positive | Vimentin (+++), Ki-67 (+, > 90%) | Ki-67 80%, P53 20% | |||

| Negative | CKpan, EMA, CK7, P504s, PSA | CK, CK5/6, P63, Gata-3, CD34, DES, SMA, myogenin, S100, HMB45, MelanA | |||

Case 2: The volume of residual urine was approximately 291 mL. A TURP and TURBT were performed. A white, narrow pedicled globe protruded from the prostate to the bladder, and its sections were fish-like (Figure 1D-F). The patient is still alive with no dysuria. The histopathology specimen showed a high-grade sarcoma, consistent with pleomorphic liposarcoma (FNCLCC G3) (Figure 1G and H). The structures of the prostate and bladder tissues were similar under the microscope. Diverse cells, such as lipoblasts, immature small round cells, subepithelial cells, spindle cells and tumor giant cells were mixed with sparse prostate cells. The mitotic figures were counted as 12/2 mm. There was massive necrosis and interstitial vein thrombosis. Immunohistochemistry showed that P504 was negative in the hyperplastic prostate (Table 1).

Case 1: The patient was readmitted for dysuria 10 mo later. A CT scan showed an irregular mixed density range approximately 4.7 cm × 4.8 cm × 4.2 cm in the previous operation area with heterogeneous enhancement (Figure 2B and C). The CT value was 50 HU in the plain scan and 82 HU in the enhanced image. Necrosis and an area of liquefaction were observed in the mass. The surface of the mass was not smooth, but the boundary of the rectum was still clear. The bladder wall was pushed upwards (Figure 2C). The mass extended from the lateral wall of the bladder to the internal orifice of the urethra. It was red in color and extremely soft. The appearance resembled a clot, and the texture was liver-like (Figure 2B).

Case 2: A 4.1 cm × 3.0 cm × 4.0 cm tumor with marked inhomogeneous enhancement was observed on CT imaging (Figure 1B and C).

The final diagnosis in both patients was SC of the prostate with bladder invasion shortly after androgen deprivation for prostate adenocarcinoma.

Radiochemotherapy was not accepted by case 1 after TURP. The second case accepted only TURP, and radiochemotherapy was not performed in this patient.

Case 1 died eight months later. The second case accepted only TURP and was satisfied with the improvement of his dysuria. He is still alive.

SC of the prostate is a rare disease with slightly over 100 reported cases in the English literature[1]. Early localized prostate SCs can be effectively treated with prostatectomy and/or radiation. However, the prognosis is very poor in patients with bladder invasion whether the treatment is hormonal therapy, cystoprostatectomy, radiotherapy or chemotherapy[5]. Extensive TURP combined with radiation therapy seems to have a limited effect in delaying the progression of SCs[4,5].

The study from Johns Hopkins University suggests that the sarcomatoid component may be androgen-independent[1]. This is based on its lack of a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) or radiographic response to androgen deprivation. Our data strongly support these views since the tumors in our two cases arose shortly after orchiectomy.

In the current study, the morphological characteristics of the sarcomatoid components were recorded. The mass resected in the second operation of the first case was red and very soft like liver, very unlike the tissues removed during the first operation in case 1 (Figure 2B, arrow). The new texture was called “red hepatization of the prostate” and was easily differentiated from blood clots, prostatic cancer, and normal bladder tissue. In case 2, the bladder tumor was only found one week before surgery, although the patient underwent 4 cystoscopes within the previous 5 mo. The white, fish flesh-like, narrow pedicled globe protruded from the prostate to the bladder (Figure 1B and C). We can conclude that the masses in our cases developed within 5 to 10 mo after castration as the sarcomatoid component tends to grow rapidly[6]. However, the average interval between the original diagnosis and the detection of an SC has been reported to be 6.8 years (6 mo to 16 years) and 8.3 years (9 mo to 20 years), respectively[3].

Our study results suggest that SCs may originate from a special group of hormonal resistant prostate stromal cancer cells found near the bladder neck and they may accelerate their growth when exposed to stimulation and changes in their environment. The bladders were normal in appearance in the first and second operations in the current cases. Various heteromorphic tumor cells showed infiltrating growth, which included immature small round cells, subepithelial cells, spindle cells, lipoblasts and tumor giant cells, etc (Figure 1G and H). The tumors were located near the proximal of the caruncle in the current cases and the tumor was limited to the bladder neck and proximal end of the prostate.

Several clues showed that the tumors arose from the prostate in the present cases. At first, the liver-like textures were mainly located in the junction of the prostate with the bladder, but they were also scattered and distributed on the distant part of the seminal colliculus in case one. The spherical lesions mainly arose from the 8 to 11 o'clock position of the prostate in case 2 (Figure 1D-F and Supplementary material). Second, the tumor may be derived from the transition zone[4] or the peripheral zone of the prostate near the bladder neck (Figure 1B-F and Figure 2C).

Consistent with the majority of SC patients with a prior history of adenocarcinoma, both of the current cases had a history of adenocarcinoma and underwent hormonal deprivation therapy. The most common clinical presentation was local symptoms. A worsened progressive intensive dysuria resulting in acute urinary retention is the major symptom[7]. The very soft mass near the internal orifice of the urethra also resulted in dysuria in case 1. The intraurethral orifice was blocked by a spherical tumor in case 2 (Figure 1D-F).

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition may contribute to an aggressive malignant process[8]. A poor prognosis, castration resistance, chemoresistance, and cancer stem cell generation are associated with an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer. Animal research into specific transcription factors showed that they could convert mouse adult fibroblasts into hepatocyte-like cells[9]. Moreover, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition allows cancer cell phenotypic plasticity for rapid adaptation to targeted therapy. A metastatic prostate cancer patient undergoing PARP inhibitor treatment will experience upregulation of cancer stem cells followed by drug resistance[10]. Conversion to a mesenchymal state would benefit the invasion of tumor cells but inhibit their stemness, and therefore, hybrid epithelial and mesenchymal traits favor the ability of tumor self-renewal and initiation capacity[11].

The ability of cancer cells to transition from one stipulated developmental pathway to another pathway is known as lineage plasticity. Lineage plasticity acts as a source of intratumoral heterogeneity and an adaptation to therapeutic resistance. Cancer cell conversion into different histological subtypes may help achieve therapeutic resistance. A typical pathway of lineage plasticity is the neuroendocrine transformation of prostate adenocarcinoma in the presence of antiandrogens[12]. SCs may be another pathway of lineage plasticity during prostate adenocarcinoma progression and therapy resistance. The main disadvantage of our study is the lack of epigenetic data.

We present the morphological characteristics of the sarcomatoid components of prostate tumors with bladder invasion. Red hepatization of the prostate and the presence of white “fish flesh” were the primary morphological characteristics of these SCs. SCs have a poor prognosis and may originate from a special group of hormonal resistant prostate stromal cancer cells. Radiation therapy and extensive TURP may be the treatments of choice for SCs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vikey AK S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Markowski MC, Eisenberger MA, Zahurak M, Epstein JI, Paller CJ. Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Prostate: Retrospective Review of a Case Series From the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Urology. 2015;86:539-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McKenney JK. Mesenchymal tumors of the prostate. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:S133-S142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hansel DE, Epstein JI. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: a study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1316-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stamatiou K, Galariotis N, Olympitis M, Papadopoulos P, Moschouris H, Lambrakopoulos A. Prostate sarcomatoid carcinoma as accidental finding in transurethral resection of prostate specimen. A case report and systematic review of current literature. G Chir. 2011;32:23-28. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Shannon RL, Ro JY, Grignon DJ, Ordóñez NG, Johnson DE, Mackay B, Têtu B, Ayala AG. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate. A clinicopathologic study of 12 patients. Cancer. 1992;69:2676-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Farag M, Ta A, Shankar S, Wong LM. Secondary spindle cell sarcoma following external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a rare but devastating complication. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zizi-Sermpetzoglou A, Savvaidou V, Tepelenis N, Galariotis N, Olympitis M, Stamatiou K. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:319-322. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Pistore C, Giannoni E, Colangelo T, Rizzo F, Magnani E, Muccillo L, Giurato G, Mancini M, Rizzo S, Riccardi M, Sahnane N, Del Vescovo V, Kishore K, Mandruzzato M, Macchi F, Pelizzola M, Denti MA, Furlan D, Weisz A, Colantuoni V, Chiarugi P, Bonapace IM. DNA methylation variations are required for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induced by cancer-associated fibroblasts in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:5551-5566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Navas T, Kinders RJ, Lawrence SM, Ferry-Galow KV, Borgel S, Hollingshead MG, Srivastava AK, Alcoser SY, Makhlouf HR, Chuaqui R, Wilsker DF, Konaté MM, Miller SB, Voth AR, Chen L, Vilimas T, Subramanian J, Rubinstein L, Kummar S, Chen AP, Bottaro DP, Doroshow JH, Parchment RE. Clinical Evolution of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2020;80:304-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laudato S, Aparicio A, Giancotti FG. Clonal Evolution and Epithelial Plasticity in the Emergence of AR-Independent Prostate Carcinoma. Trends Cancer. 2019;5:440-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Quintanal-Villalonga Á, Chan JM, Yu HA, Pe'er D, Sawyers CL, Sen T, Rudin CM. Lineage plasticity in cancer: a shared pathway of therapeutic resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:360-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |