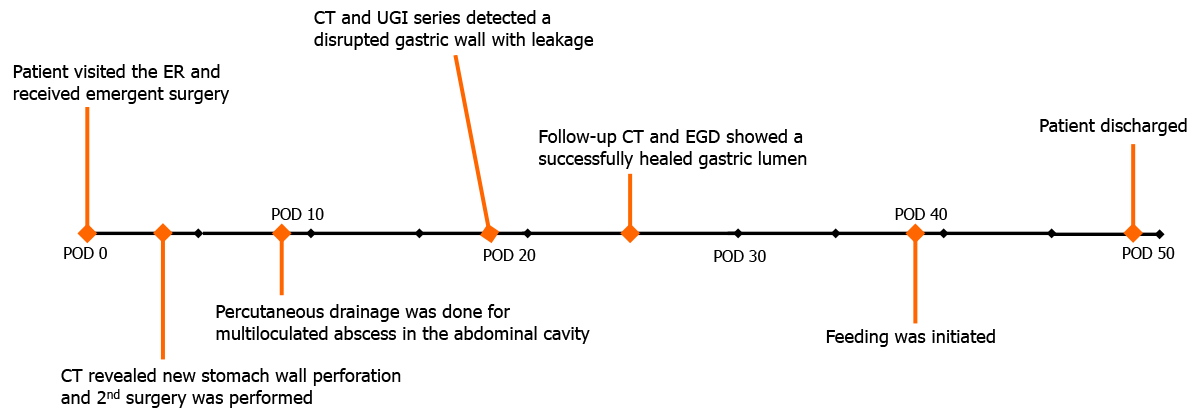

Published online Feb 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1228

Peer-review started: November 26, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 13, 2020

Accepted: December 29, 2020

Article in press: December 29, 2020

Published online: February 16, 2021

Processing time: 64 Days and 21.5 Hours

Primary endoscopic closure of a perforated gastric wall during endoscopic procedures is mostly effective and well-tolerated; however, there are very few studies on the efficacy of endoscopic management of delayed traumatic gastric perforation. Herein, we report a novel case of a patient who was successfully treated for delayed traumatic stomach perforation using an alternative endoscopic modality.

A 39-year-old woman presented with multiple penetrating traumas in the back and left abdominal cavity. Initial imaging studies revealed left diaphragmatic disruption and peri-splenic hemorrhage without gastric perforation. An emergency primary repair of the disrupted diaphragm with omental reduction and suturing of the lacerated lung was performed; however, delayed free perforation of the gastric wall was noted on computed tomography after 3 d. Following an emergency abdominal surgery for the primary repair of the gastric wall, re-perforation was noted 15 d postoperatively. The high risk associated with re-surgery prompted an endoscopic intervention using 2 endoloops and 11 endoscopic clips using a novel modified purse-string suture technique. The free perforated gastric wall was successfully repaired without additional surgery or intervention. The patient was discharged after 46 d without any complications.

Endoscopic closure with endoloops and clips can be a useful therapeutic alternative to re-surgery for delayed traumatic gastric perforation.

Core Tip: Primary closure of a perforated gastric wall caused by penetrating trauma has mostly been treated with surgery, and the role of endoscopy is not well established. This case report describes the successful closure of a free perforated gastric wall using a modified purse-string technique involving endoloops and endoscopic clips. This technique successfully managed delayed re-perforation of the stomach without complications or subsequent surgery. The modified purse-string technique can be a useful therapeutic alternative to re-surgery for delayed gastric perforation, contributing to lower invasiveness and faster recovery.

- Citation: Yoon JH, Jun CH, Han JP, Yeom JW, Kang SK, Kook HY, Choi SK. Endoscopic repair of delayed stomach perforation caused by penetrating trauma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(5): 1228-1236

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i5/1228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1228

Stomach perforation due to trauma is an emergent critical condition, and immediate management of the perforated gastric wall is essential. Gastric trauma has a high mortality rate (19%-43%), and a majority of cases require primary surgical repair[1].

Although surgical management of gastric perforation is generally effective for traumatic stomach perforation, in situations where surgery is not feasible or in stable patients without sepsis, endoscopic treatment modalities can be considered. The endoscopic treatment method with an endoloop and clips (purse-string suture technique) has been shown to have good results for large iatrogenic gastrointestinal (GI) perforation closures after endoscopic therapeutic procedures[2-4]. In addition, one case report described successful closure of a small gastric penetrating stab wound with clips[5]. Endoscopic treatment might be an effective option to treat GI perforation because it is minimally invasive, associated with fast recovery, and has relatively low costs compared with surgery[6]. However, there are limited data on the efficacy of endoscopic closures for trauma-induced delayed GI tract perforation and anastomotic leakage.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report on the successful execution of a novel modified endoscopic purse-string suture technique for delayed stomach perforation after primary surgical repair.

A 39-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department due to multiple penetrating stab wounds from a knife (Figure 1).

She complained of pain on the back and right flank area with severe pain, and further elaborated that she was stabbed with a sharp knife four times on the upper back near the medial margin of right scapula and once on the flank side of the right abdomen.

The patient had no underlying comorbidities.

The patient’s personal and family history are not part of this case report.

The vital signs on admission were stable (blood pressure: 120/60 mmHg, heart rate: 84 beats/min, respiratory rate: 16 cycles/min, and body temperature: 36.4 °C). Physical examination revealed four stab wounds on the upper back and one on the left flank with herniated omental fat. There were no definite physical signs of pan-peritonitis.

The initial laboratory examination in the emergency department showed a white blood cells count of 10800/mm3, hemoglobin level of 11.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 256000/mm3. Liver and renal functions, coagulation profile, and C-reactive protein were all within normal levels.

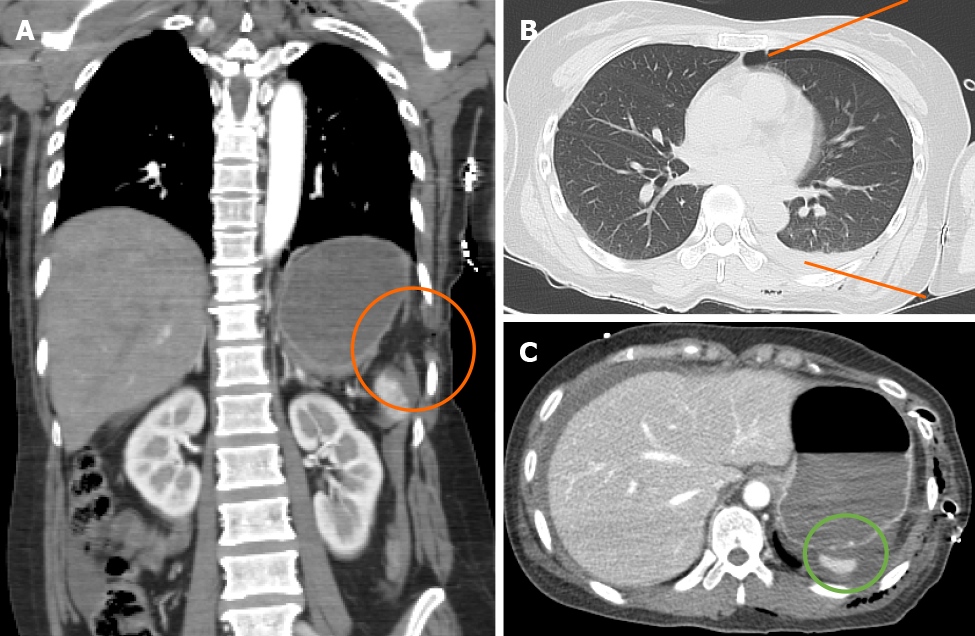

Initial computed tomography (CT) revealed a left hemopneumothorax and focal diaphragmatic disruption (Figure 2A) with left lower lobe and splenic lacerations and hematomas in the perisplenic space and the lesser sac (Figure 2B). No definite stomach perforation, mucosal defect, or intraluminal hematoma were observed on initial CT scanning (Figure 2C).

The final diagnosis of the case was left hemopneumothorax, focal diaphragmatic disruption, and splenic lacerations with hematomas. Furthermore, delayed stomach perforation was diagnosed after initial evaluation and treatment.

An emergency primary repair of the disrupted diaphragm was performed with omental fat reduction and suturing of the lacerated lung. Follow-up CT performed on 1st postoperative day (POD) revealed increased amount of hemoperitoneum without evidence of active bleeding or gastric perforation. The hemoperitoneum secondary to minor splenic laceration was closely monitored without further surgery.

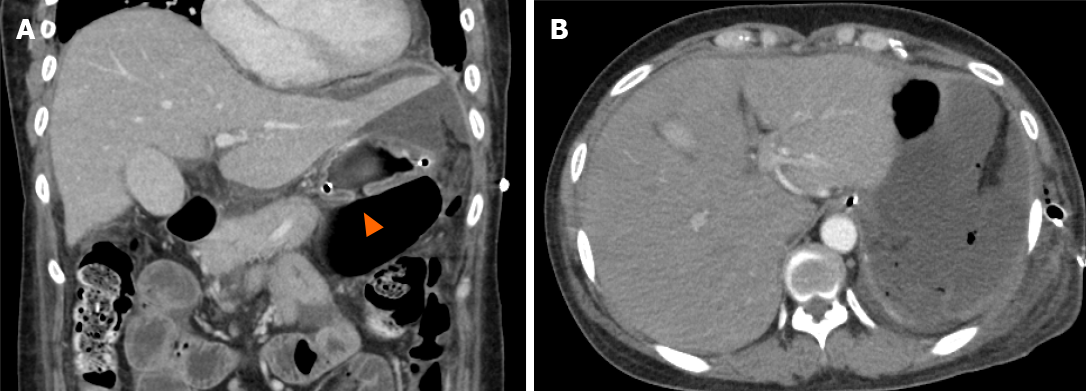

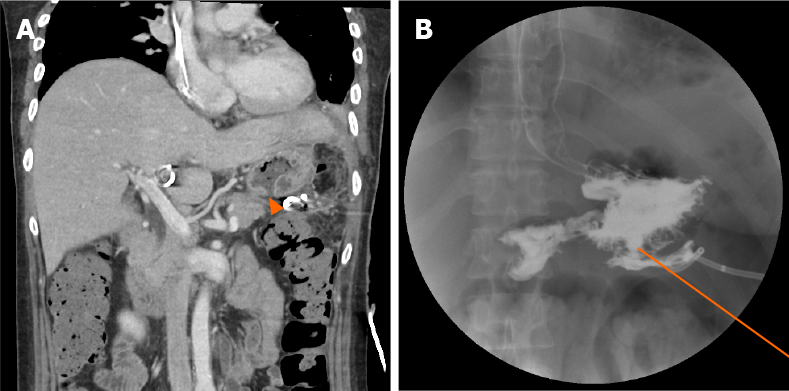

On 3rd POD, tachycardia, low-grade fever, and decreased serum hemoglobin were observed. Follow-up CT revealed free perforation of the upper gastric posterior wall (PW), with newly developed hemoperitoneum and pneumoperitoneum (Figure 3A and B). A second emergency surgery revealed a 3-cm-long free perforation in the PW of the upper stomach, with severe surrounding inflammation. Primary repair of the perforated gastric wall was performed. Four drainage tubes were inserted in the intra-abdominal cavity, and a small amount of serous fluid was drained. However, the tubes were later forcibly removed by the patient due to postoperative delirium. On 9th POD, follow-up CT revealed peritonitis with a multi-loculated abscess in the upper abdominal cavity, which was drained using a percutaneous drainage (PCD) catheter. An upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series that was performed on 12th POD with gastrografin to screen for possible undetected small perforations showed no signs of leakage at the perforation site. The daily amount of PCD decreased; however, CT on 18th POD detected disrupted gastric wall with residual fluid collection. Another UGI series revealed prominent leakage (Figure 4A and B). Due to the short 14-d interval from the most recent surgery, severe adhesions and inflammation in the surgical field were presumed. Therefore, there was high risk associated with re-surgery. Hence, we decided to conduct a primary closure using a double-channel endoscope (GF UCT 260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) under sedation with intravenous propofol.

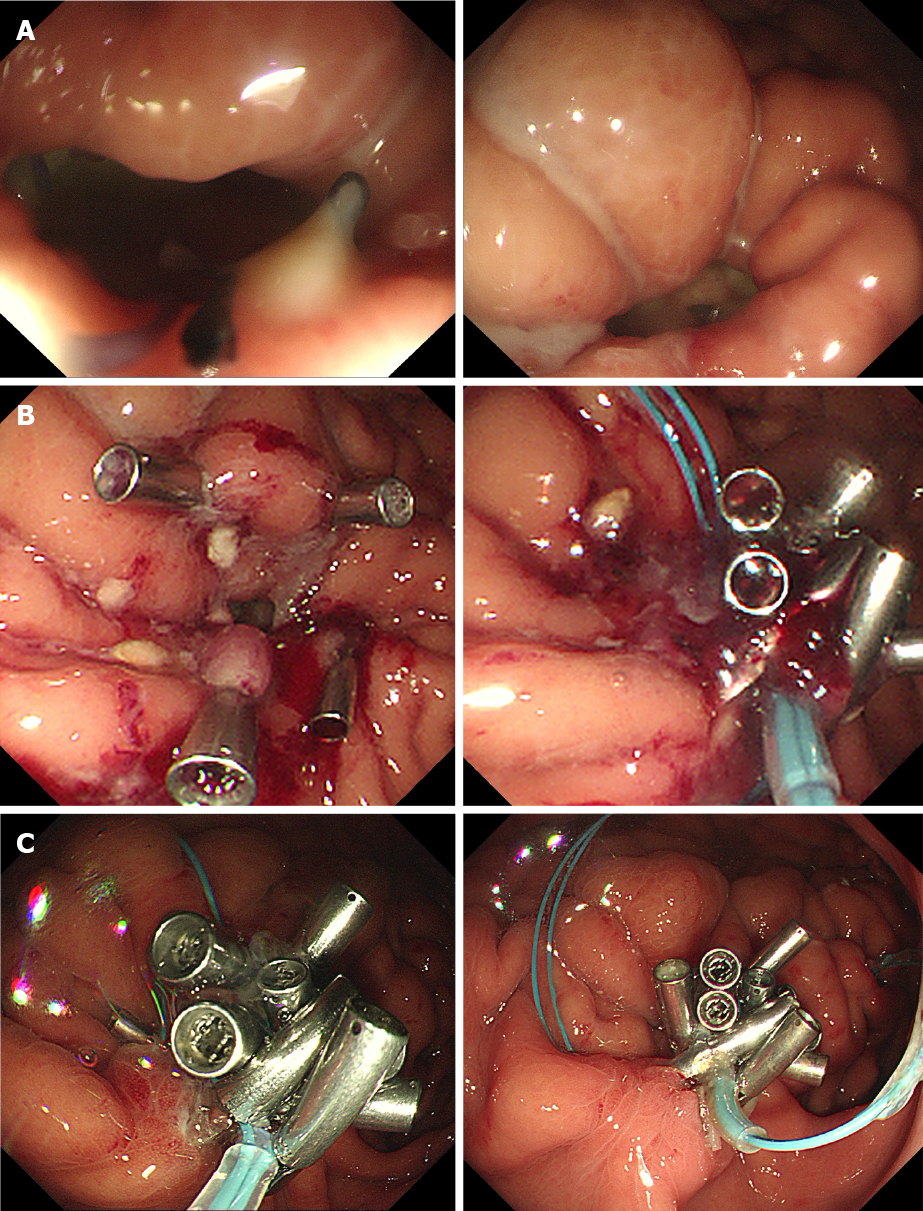

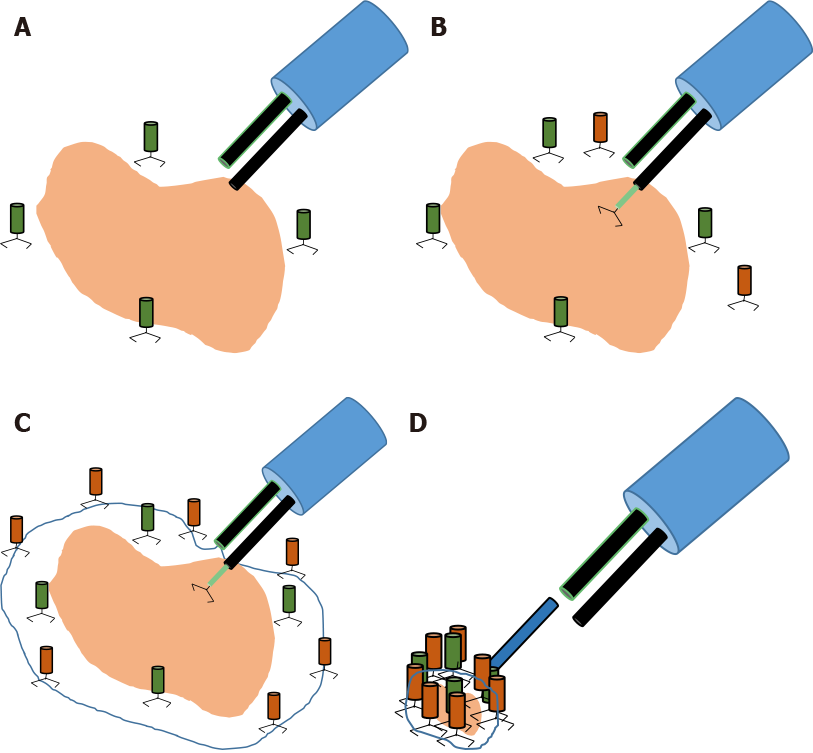

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a 2-cm free perforation in the gastric wall of the upper-body/greater-curvature with a large amount of pus draining into the stomach cavity via the perforated lumen (Figure 5A). Steps for the purse-string technique were undertaken as follows: First, an endoloop was placed at the perforation site. The first clip was then placed at the proximal defect site, and the endoloop was anchored on the mucosa of the perforated lesion. The subsequent clips fixed the endoloop beside the previous clips. After the endoloop and clips encircled the defect, the rim of the opening was approximated by fastening the endoloop using the purse-string technique[7]. However, because of severe edema and friability of the gastric mucosa, we attached four fixing clips (OptimosTM disposable clip, Taewoong Medical, Gimpo, South Korea) as pillars on the margin of the perforated lumen in advance (Figure 6). Then, we placed an endoloop (HX-20U-1; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) encircling the margin of the attached clips and fixed it to the gastric mucosa using 7 additional endoscopic clips (Figure 5B). Finally, we fastened the endoloop, which tightened and secured the perforated lumen (Figure 5B).

Follow-up CT and EGD at 25th POD revealed a successfully healed gastric lumen and decreased loculated fluid collection (Figure 5C). Feeding was initiated on 39th POD, and the patient was discharged on 46th POD without other complications.

From the patient’s perspective, since she had previously experienced the pain and discomfort associated with surgery under general anesthesia, she was satisfied with the short endoscopic procedure time and the absence of post-procedural discomfort. After discharge, she thanked our team at the outpatient clinic for deciding to perform a primary endoscopic closure rather than a second open surgery.

Delayed gastric perforation may be caused by trauma, malignant tumors, benign ulcers, or iatrogenic factors such as complications of UGI) surgery, placement of percutaneous gastrostomy, and endoscopic procedures[8-10]. Severe gastric injuries secondary to penetrating abdominal trauma occur in 7%-20% of the cases and are associated with several complications[11]. Injuries to other visceral organs can occur in 65%-74% of the cases[12], and liver lacerations can co-exist with these injuries, especially diaphragmatic injury[13]. Physicians should be aware of delayed gastric perforation because a superficial injury to the gastric wall can progress to free perforation[14]. Although CT scan is known to have low sensitivity in detecting uncomplicated gastric mucosal ulceration[15,16], in our case, the initial CT scan showed splenic hemorrhage with diaphragmatic injury. Eventually the patient developed free gastric perforation after 3 d with symptoms of severe abdominal pain and tenderness associated with fever which is known as the major symptoms of delayed perforation[17-19]. GI tract perforation may present acutely (usually chest or abdominal pain), or in an indolent manner (in case of abscess or intestinal fistula formation). Usually diagnosis is made primarily using abdominal imaging studies, but on occasion, exploratory laparotomy may be needed. Specific treatment depends upon the nature of the disease process that caused the perforation. Some etiologies are amenable to a non-operative approach, while others will require emergent surgery[20,21]. We believe that a thorough surgical exploration of the abdominal cavity during the first surgery could have prevented delayed gastric perforation[12,22]. Furthermore, we believe that the second delayed perforation of the stomach wall occurred because of perigastric fluid accumulation that may have interrupted stomach wall healing.

The treatment modality differs depending on the etiology and severity of gastric perforation. Therapeutic endoscopy can promptly identify free perforation of the gastric wall, thereby allowing adequate and successful management. Accordingly, recent studies have demonstrated good results for on-site endoscopic closure of GI tract perforations[3,23]. However, the immediate detection and management of free perforation may be difficult in cases of gastric perforation from an external force, such as blunt or penetrating trauma. With delayed perforation, endoscopic closure of the perforation site may be challenging because of bowel edema, inflammation, and fibrosis of the surrounding tissues.

Our case suggests that when surgery is unfeasible owing to unexpected patient conditions, such as delayed gastric re-perforation or leakage from the repair site, salvage treatment using endoscopy may be preferable to re-surgery, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality[24]. Endoloops and endoscopic clips for the closure of GI tract perforations are effective treatment modalities[2,3]. However, existing studies have reported only on the efficacy of on-site endoscopic closure for early GI perforation, and have limited data on delayed GI tract perforation and anastomotic leakage after trauma. Our case offers a novel technique for these situations.

Unlike perforated gastric wall during the endoscopic procedure with its intact margin and preserved elasticity, delayed perforated gastric wall is likely to appear swollen with friable mucosa which may not be feasible for conventional purse-string technique since grasping of perforated lumen by fixation of endoloop without pillar clips will be quite challenging and is likely to fail. Thus, using the modified purse-string technique (placing the “pillar clips” before the endoloop to retain sufficient margin of the perforated lumen) may be more appropriate as shown in our case. Additionally, an extensive abdominal examination during the first surgery could have identified the gastric injury and prevented perforation and complications. Therefore, thorough surgical exploration of the abdominal cavity should be considered in cases of abdominal trauma, especially those with penetrating diaphragmatic injury.

This report has some limitations. Due to limited number of enrolled patients and lack of previous clinical studies, it is difficult to generalize modified purse-string technique in clinical circumstances of delayed gastric perforation due to trauma. Further comparative studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of this technique is warranted.

In conclusion, endoscopic treatment using this novel modified purse-string technique can successfully manage delayed re-perforation of the stomach due to trauma, without complications or subsequent surgery. The successful implementation of the modified purse-string technique in this case merits further study for both safety and efficacy in large-scale trials.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Deng JY, He YF, Sun SY S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Edelman DA, White MT, Tyburski JG, Wilson RF. Factors affecting prognosis in patients with gastric trauma. Am Surg. 2007;73:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ryu JY, Park BK, Kim WS, Kim K, Lee JY, Kim Y, Park JY, Kim BJ, Kim JW, Choi CH. Endoscopic closure of iatrogenic colon perforation using dual-channel endoscope with an endoloop and clips: methods and feasibility data (with videos). Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1342-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shi D, Li R, Chen W, Zhang D, Zhang L, Guo R, Yao P, Wu X. Application of novel endoloops to close the defects resulted from endoscopic full-thickness resection with single-channel gastroscope: a multicenter study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:837-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dabizzi E, De Ceglie A, Kyanam Kabir Baig KR, Baron TH, Conio M, Wallace MB. Endoscopic "rescue" treatment for gastrointestinal perforations, anastomotic dehiscence and fistula. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:28-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Addley J, Ali S, Lee J, Taylor M, Lowry P, Mitchell RM. Endoscopic clip closure of penetrating stab wound to stomach. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E219-E220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sun K, Chen S, Ye J, Wu H, Peng J, He Y, Xu J. Endoscopic resection versus surgery for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:513-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shi Q, Chen T, Zhong YS, Zhou PH, Ren Z, Xu MD, Yao LQ. Complete closure of large gastric defects after endoscopic full-thickness resection, using endoloop and metallic clip interrupted suture. Endoscopy. 2013;45:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seicean A, Cruciat C, Motocu R, Pojoga C, Gheorghiu M, Seicean R. Rescue Therapy of Delayed Gastric Perforation Caused by an External Drainage Using an Over-the-Scope Clip. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019;28:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Revell MA, Pugh MA, McGhee M. Gastrointestinal Traumatic Injuries: Gastrointestinal Perforation. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;30:157-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coskun AK, Yarici M, Ulke E, Mentes O, Kozak O, Tufan T. Perforation of isolated jejunum after a blunt trauma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25: 862.e1-862. e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Durham RM, Olson S, Weigelt JA. Penetrating injuries to the stomach. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172:298-302. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Leppäniemi A, Haapiainen R. Diagnostic laparoscopy in abdominal stab wounds: a prospective, randomized study. J Trauma. 2003;55:636-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee SH, Chou SH, Kao EL. Diaphragmatic injury. Gaoxiong Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 1991;7:622-627. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sung CK, Kim KH. Missed injuries in abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1996;41:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shin D, Rahimi H, Haroon S, Merritt A, Vemula A, Noronha A, LeBedis CA. Imaging of Gastrointestinal Tract Perforation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2020;58:19-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Milosavljevic T, Kostić-Milosavljević M, Jovanović I, Krstić M. Complications of peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis. 2011;29:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamamoto Y, Nishisaki H, Sakai H, Tokuyama N, Sawai H, Sakai A, Mimura T, Kushida S, Tsumura H, Sakamoto T, Miki I, Tsuda M, Inokuchi H. Clinical Factors of Delayed Perforation after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Gastric Neoplasms. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:7404613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamoto Y, Kikuchi D, Nagami Y, Nonaka K, Tsuji Y, Fujimoto A, Sanomura Y, Tanaka K, Abe S, Zhang S, De Lusong MA, Uedo N. Management of adverse events related to endoscopic resection of upper gastrointestinal neoplasms: Review of the literature and recommendations from experts. Dig Endosc. 2019;31 Suppl 1:4-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suzuki H, Oda I, Sekiguchi M, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Nakajima T, Saito Y. Management and associated factors of delayed perforation after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12635-12643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Boccola MA, Buettner PG, Rozen WM, Siu SK, Stevenson AR, Stitz R, Ho YH. Risk factors and outcomes for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a single-institution analysis of 1576 patients. World J Surg. 2011;35:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jacobsen HJ, Nergard BJ, Leifsson BG, Frederiksen SG, Agajahni E, Ekelund M, Hedenbro J, Gislason H. Management of suspected anastomotic leak after bariatric laparoscopic Roux-en-y gastric bypass. Br J Surg. 2014;101:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Agresta F, Ansaloni L, Baiocchi GL, Bergamini C, Campanile FC, Carlucci M, Cocorullo G, Corradi A, Franzato B, Lupo M, Mandalà V, Mirabella A, Pernazza G, Piccoli M, Staudacher C, Vettoretto N, Zago M, Lettieri E, Levati A, Pietrini D, Scaglione M, De Masi S, De Placido G, Francucci M, Rasi M, Fingerhut A, Uranüs S, Garattini S. Laparoscopic approach to acute abdomen from the Consensus Development Conference of the Società Italiana di Chirurgia Endoscopica e nuove tecnologie (SICE), Associazione Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani (ACOI), Società Italiana di Chirurgia (SIC), Società Italiana di Chirurgia d'Urgenza e del Trauma (SICUT), Società Italiana di Chirurgia nell'Ospedalità Privata (SICOP), and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2134-2164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Abe S, Minagawa T, Tanaka H, Oda I, Saito Y. Successful endoscopic closure using over-the-scope clip for delayed stomach perforation caused by nasogastric tube after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E56-E57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hyman NH. Managing anastomotic leaks from intestinal anastomoses. Surgeon. 2009;7:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |