Published online Feb 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1210

Peer-review started: November 17, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 21, 2020

Accepted: January 7, 2021

Article in press: January 7, 2021

Published online: February 16, 2021

Processing time: 65 Days and 22 Hours

Vibrio pararhaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus), a pathogen that commonly causes gastroenteritis, could potentially lead to a pandemic in Asia. Its pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms vary, and the severity of illness can be diverse, ranging from mild gastroenteritis, requiring only supportive care, to sepsis.

We outline a case of a 71-year-old female who experienced an acute onset of severe abdominal tenderness after two days of vomiting and diarrhea prior to her emergency department visit. A small bowel perforation was diagnosed using computed tomography. The ascites cultured revealed infection due to V. parahaemolyticus

Our case is the first reported case of V. parahaemolyticus-induced gastroenteritis resulting in small bowel perforation.

Core Tip: Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a pathogen commonly associated with gastroenteritis following the consumption of seafood. Aside from supportive treatment with hydration and oral antibiotics, clinicians must be aware of the possible complication of acute abdomen which may require surgical intervention.

- Citation: Chien SC, Chang CC, Chien SC. Spontaneous small bowel perforation secondary to Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection: A case report . World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(5): 1210-1214

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i5/1210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1210

Vibrio pararhaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus) is a gram negative bacterium that can cause various infections, such as acute gastroenteritis and skin infection through wound contamination[1]. Infection typically results from the consumption of seafood, such as shellfish, or exposure to seawater. This pathogen is commonly responsible for pandemics in Asia with increasing frequency in Western countries in warmer months[1].

Symptoms of V. parahaemolyticus-induced gastroenteritis include abdominal cramping and pain, watery diarrhea, headache, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever. In the majority of cases, symptoms are usually self-limiting in immuno-competent patients who are adequately hydrated[2]. Occasionally, antibiotics, such as azithromycin and ciprofloxacin, may be indicated[3]. V. parahaemolyticus infection may progress to more severe conditions such as septicemia through intestinal invasion[4] due to underlying stress or other risk factors including cancer; liver, kidney, and heart diseases, recent gastric surgery, and antacid use[5].

The spectrum of disease is diverse due to its complex virulence factors. We present a case of V. parahaemolyticus-induced acute gastroenteritis complicated by spontaneous small bowel perforation.

A 71-year-old woman presented to our emergency department with complaints of acute-onset, severe abdominal cramping pain that started several hours prior to arrival.

Forty-eight hours prior to presentation, the patient had experienced several vomiting episodes as well as 6-7 episodes of watery diarrhea per day.

She had a history of hypertension controlled by medication.

On arrival, her vital signs were as follows: Temperature was 37.3 °C; heart rate was 83 beats/min; respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min; blood pressure was 99/64 mmHg; and pulse oximetry (SPO2) was 97%. She was fully conscious (Glasgow Coma Scale: E4V5M6). Physical examination revealed mild abdominal tenderness, and the abdomen was tympanic on percussion.

Laboratory data revealed leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance [white blood cell count: 10600/μL (normal: 4000-10000/μL), neutrophil percentage: 88.6% (normal: 55-75%)], and pre-renal azotemia [blood urine nitrogen: 22.1 mg/dL (normal: 8-20 mg/dL) and creatinine: 0.59 mg/dL (normal: 0.4-1.2 mg/dL)]. No elevated C-reactive protein levels or coagulopathy were noted. A general urine examination revealed no pyuria. Because of her peritoneal signs, we scheduled an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan for further evaluation.

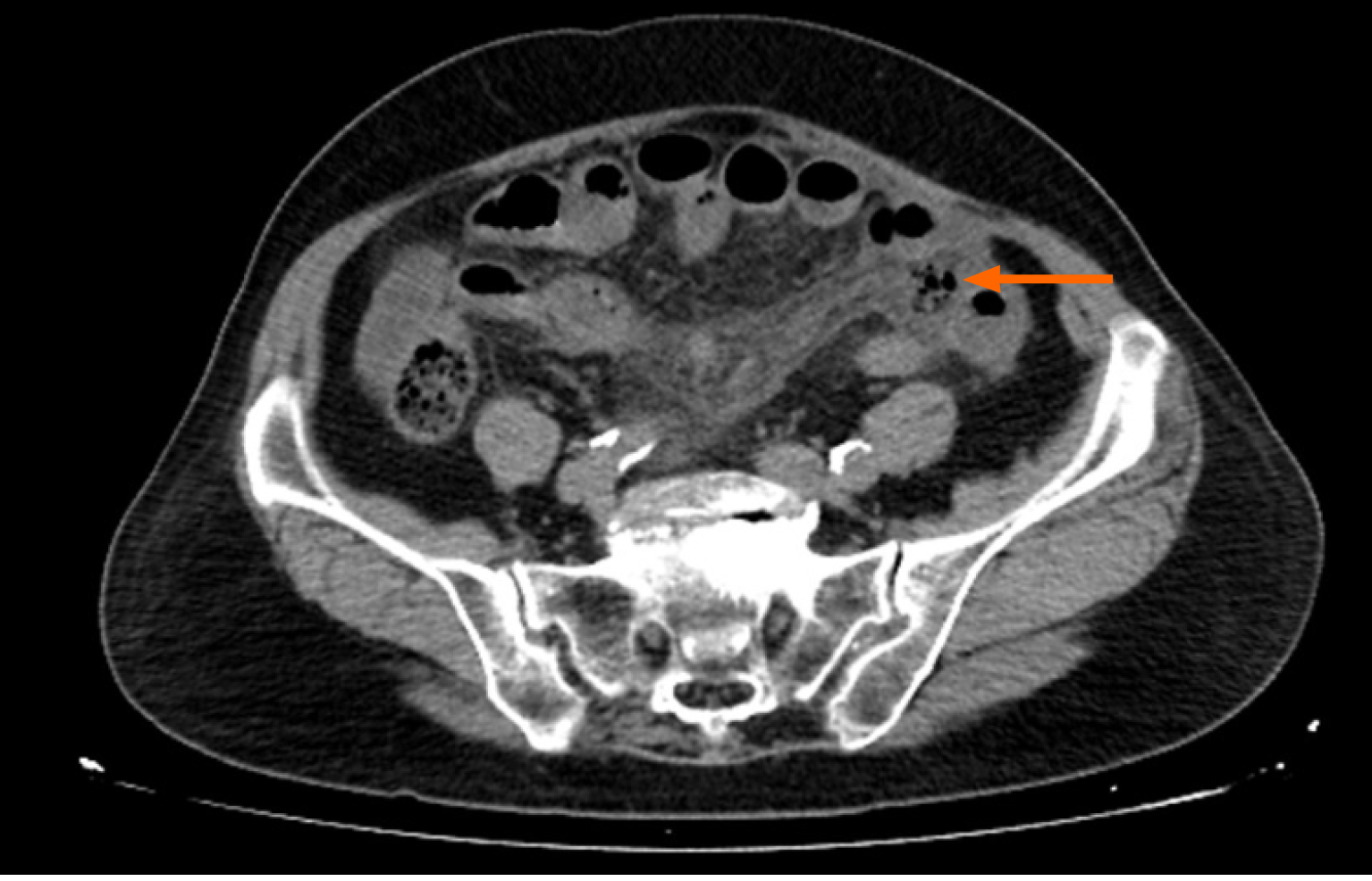

The abdominal CT scan with and without contrast medium revealed multiple, focal areas of extraluminal air in the left lower mesentery with adjacent small bowel edema, accompanied by focal congested mesentery and small ascites in the coronal section (Figure 1).

Based on these findings, a small bowel perforation secondary to an V. Parahaemolyticus infection was made.

For symptomatic control, we administered 30 mg of intravenous ketorolac tromethamine, 20 mg of hyoscine butyl bromide, and 5 mg of prochlorperazine. For infection control, ertapenem (1 g) was given daily for 10 d. The patient was then transferred for an emergency laparotomy after consulting with a general surgeon.

The general surgeon elected to perform open surgery to better survey the abdominal cavity. A necrotic perforation was noted 80 cm from the ileocecal junction (Figure 2). A wedge resection encompassing the perforation was performed, followed by the creation of an end-to-end anastomosis. A Jackson-Pratt surgical drain was inserted. The peritoneal cavity was irrigated with warm saline. Finally, the turbid ascites were evacuated, and samples were sent for culture, which revealed V. parahaemolyticus. We maintained the patient on a 10 d antibiotic course.

The patient was discharged after 10 d without any discomfort. She was followed up at the outpatient department two weeks later without any complications.

Spontaneous perforation of the small intestine is a rare sequelae of infective gastroenteritis. Several pathogens are associated with such complications including viruses (Cytomegalovirus), bacteria (Salmonella typhi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Tropheryma whipplei), fungi (histoplasmosis, candida), parasites (roundworm), and protozoans (Entamoeba histolytica)[6,7]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of V. parahaemolyticus-induced spontaneous small bowel perforation.

V. parahaemolyticus is usually managed with supportive treatment. However, it can have varied presentations in V. parahaemolyticus-induced gastroenteritis. Akeda et al[4] noted that V. parahaemolyticus may have an invasive form that allows it to invade the intestinal epithelium leading to septicemia[4]. In our case, the patient’s infection led to another life-threatening condition, a small bowel perforation. The range in disease severity is due to the complex pathogenesis of V. parahaemolyticus, which can induce chemotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and enterotoxicity. To date, there are multiple pathways that induce disease mechanisms: (1) Hemolysins, including thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH), TDH-related hemolysin, and thermolabile hemolysin; (2) Secretory systems, such as the type 3 and 6 secretory systems; (3) Adhesion factors, such as hemagglutinin and enolase; (4) Iron reuptake system; (5) Lipopolysaccharide; (6) Proteases; and (7) Outer membrane proteins[8]. The main virulence mechanisms related to enterotoxicity were: (1) TDH that increases calcium ion concentration in intestinal cells and opens the chloride channel to facilitate chloride secretion in intestinal cells; (2) Type 3 secretion system-2 which can target the cytoskeleton and manipulate cell signal transduction (the mitogen-activated protein kinase or nuclear factor-k-gene binding pathway) through different effectors (VopA, VopT, VopL, VopV, VopC, VopZ, and VPA1380), which can lead to diarrhea and facilitate bacterial invasion into the epithelium; and (3) Adhesion factors, such as mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin and nitrogen-limitation sigma factor (RpoN), which can facilitate colonization of V. parahaemolyticus in the intestine[8]. Additionally, strain-to-strain differences among V. parahaemolyticus are remarkable. The O3:K6 strain that usually induces pandemics in Asia contains the tdh gene but not the trh gene. The level of TDH may vary in different isolated strains[9]. Environmental factors such as temperature and acid-base status also play a role in pathogenesis[9]. The exact mechanism still needs clarification.

A limitation of our study is that the patient did not have a previous colonoscope survey. We cannot exclude whether there was a pre-existing congenital or acquired structure abnormality, such as Crohn's disease, lymphoma, or other underlying lesion. We also cannot exclude any underlying mesentery vascular lesions, which can, in rare cases, cause a spontaneous small bowel perforation. Additionally, we did not perform molecular studies to determine the virulence factors for this pathogenic strain of V. parahaemolyticus.

V. parahaemolyticus is a common pathogen causing acute gastroenteritis in Asia. In addition to supportive and antibiotic treatments that are typically used, it is important to be aware of the possible complications that may require surgical intervention such as small bowel perforations.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mikulic D S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Rezny BR, Evans DS. Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. 2020 Jul 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yeung PS, Boor KJ. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention of foodborne Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2004;1:74-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD, Alam M, Ali A, Waldor MK, Qadri F, Martinez-Urtaza J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 496] [Article Influence: 70.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akeda Y, Nagayama K, Yamamoto K, Honda T. Invasive phenotype of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:822-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Broberg CA, Calder TJ, Orth K. Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:992-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Freeman HJ. Spontaneous free perforation of the small intestine in adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9990-9997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Luglio G, De Palma GD, Liccardo F, Giglio MC, Sollazzo V, Zito G, Bucci L. Recurrent, spontaneous, postoperative small bowel perforations caused by invasive candidiasis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1585-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li L, Meng H, Gu D, Li Y, Jia M. Molecular mechanisms of Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogenesis. Microbiol Res. 2019;222:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong HC, Liu SH, Wang TK, Lee CL, Chiou CS, Liu DP, Nishibuchi M, Lee BK. Characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 from Asia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3981-3986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |