Published online Feb 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1204

Peer-review started: November 7, 2020

First decision: November 20, 2020

Revised: December 3, 2020

Accepted: December 26, 2020

Article in press: December 26, 2020

Published online: February 16, 2021

Processing time: 84 Days and 6.7 Hours

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) occurring in the parapharyngeal space are rare, and their final diagnosis depends on pathological and immunohistochemical analyses. Once the tumor is diagnosed, complete resection and regular postoperative follow-up are required.

A 40-year-old male patient with a right parotid gland mass discovered 8 years ago was admitted to hospital. The mass showed no tenderness or local skin redness. Imaging was carried out as the patient had stable vital signs and showed that the mass was a dumbbell-shaped tumor comprising a superficial tumor approximately 5 cm long and 3 cm wide in size that compressed the right parotid gland and a deep tumor located in the right parapharyngeal space approximately 4.5 cm long and 2.5 cm wide in size. Both tumors were connected in the middle. Prior to surgery, the tumors were considered to be parapharyngeal schwannomas. During surgical dissection, the tumors were found to be smooth and tough, without obvious adhesion to the surrounding tissues. The tumors were revealed to be a SFT following postoperative pathological analysis.

SFTs in the parapharyngeal space are rarely reported, and complete resection of such tumor is recommended. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is used in patients with extensive tumor invasion to lower the recurrence rate. Postoperative long-term follow-up is required.

Core Tip: Parapharyngeal space solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is quite rare. In this case study, a dumbbell-shaped SFT in the parapharyngeal space in a male patient is reported. The tumor was completely excised under general anesthesia, and postoperative recovery was uneventful. The diagnosis, pathology and treatment methods of SFTs are discussed in this report.

- Citation: Li YN, Li CL, Liu ZH. Dumbbell-shaped solitary fibrous tumor in the parapharyngeal space: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(5): 1204-1209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i5/1204.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1204

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a relatively rare tumor in clinical practice and is mainly seen in the pleura[1]. Head and neck SFTs mainly occur in the orbit and oral cavity[2] and are rarely found in the parapharyngeal space. Here, we report a rare dumbbell-shaped SFT in the parapharyngeal space.

A 40-year-old man was admitted to our department due to a right parotid mass that was found 8 years ago.

Over the past 8 years, the tumor had slowly increased in size. A higher temperature could be felt through the skin where the tumor was located, but no tenderness or redness was observed.

The patient had no history of surgical trauma, chronic disease or allergies.

The patient rarely drinks alcohol but has been a smoker for 20 years, with an average of one pack of cigarettes per day. His family members are in good health and have no similar diseases.

A palpable mass approximately 5 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm in size was observed near the parotid gland on the right. The mass was tough with moderate mobility, but there was no tenderness, obvious redness, swelling or pain. There were no palpable enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

No abnormalities were found on routine blood tests, biochemical examination, electrocardiogram and chest radiograph.

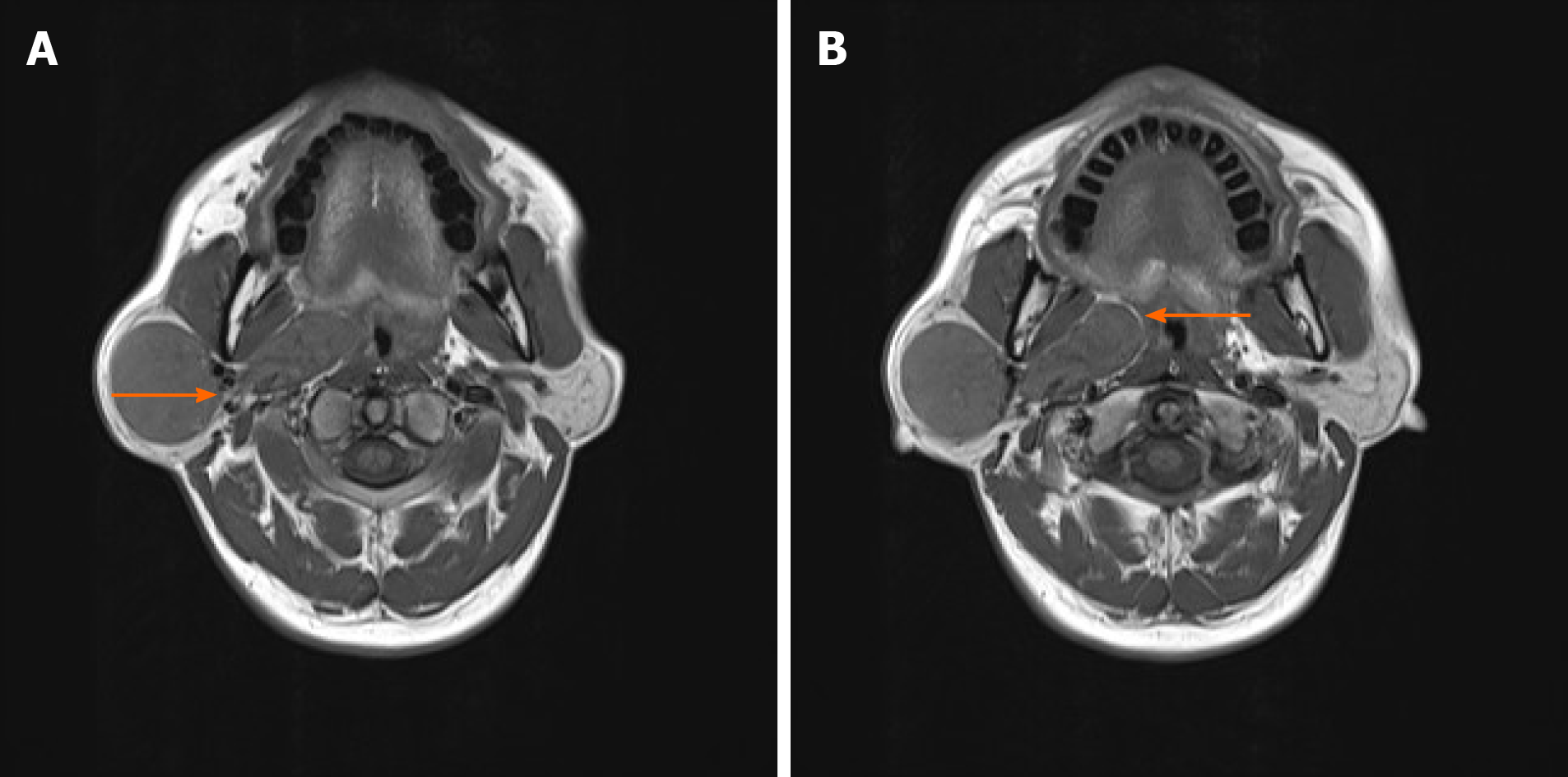

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) an isometric T1 long T2 signal mass with a clear boundary and a maximum cross-section of approximately 31 mm × 36 mm and a vertical diameter of about 50 mm was observed on the right parotid gland. At the right parapharyngeal space, irregular T1 slightly longer T2 signal masses with clear centered boundaries and a maximum cross-section of approximately 20 mm × 45 mm were found. The tumors were initially diagnosed as parotid masses, with calcium acini, parapharyngeal space irregular masses and enlarged lymph nodes, but pleomorphic adenoma was excluded. Pre-surgical reassessment of the imaging data revealed that the tumors were more likely to be a parapharyngeal space schwannoma.

SFT of the parapharyngeal space.

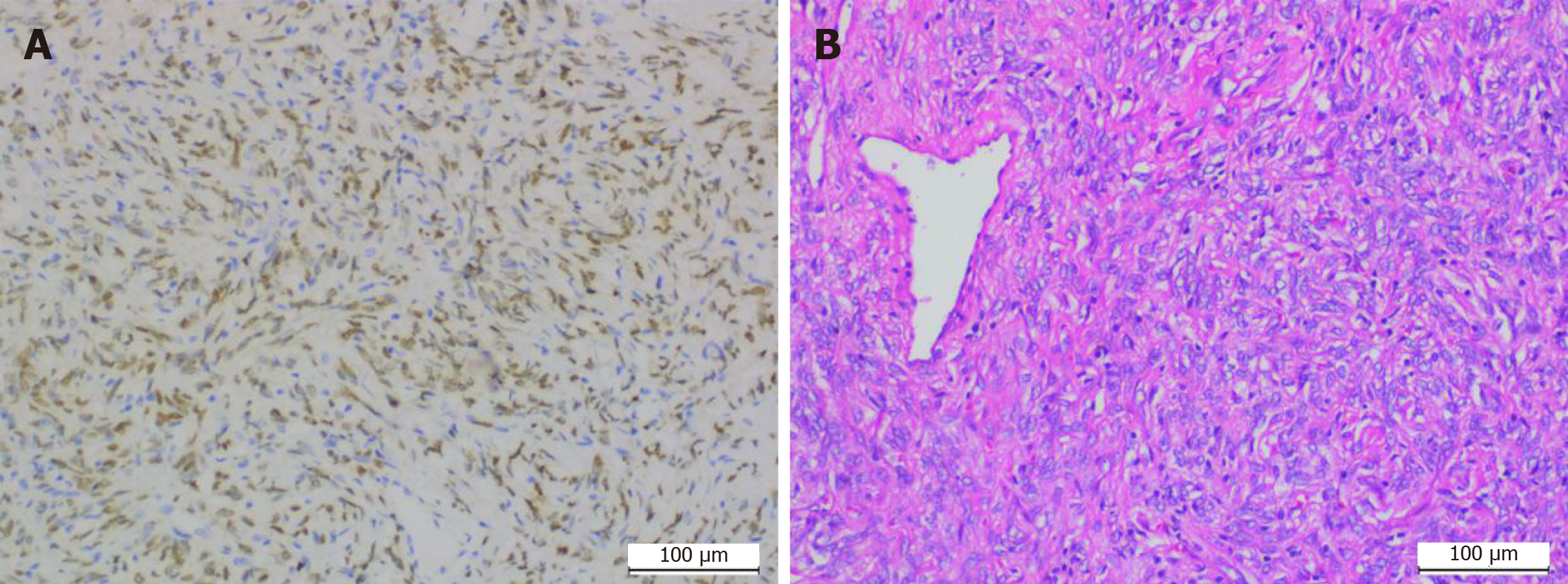

Under general anesthesia, an incision was made via a parallel path from the back of the right ear to the submandibular area to explore and to protect the facial nerve, and the tumors in the deep surface of the parotid gland and the right parapharyngeal space were completely removed (Figure 1). Postoperative pathological results revealed that the isolated tumors from the right parapharyngeal and right parotid gland were fibrous tumors (intermediate tumors). Further analysis of the tumor cells by immunohistochemistry showed vimentin (+), signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) (+), CD34 (+), smooth muscle actin (blood vessel +), beta-catenin pulp (+), CD31 (-), desmin (-), S100 (-) and Ki-67 (+ 3%) (Figure 2).

On day 5 after surgery, the patient had a slight droop in the right corner of his mouth. The nasolabial fold was normal and the brow furrow was wrinkled, but there was no discomfort in the surgical area.

Initially thought to be a type of mesothelioma, SFT is now generally believed to originate from CD34+ and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)+ dendritic mesenchymal cells. As SFTs are widely distributed in human connective tissues, they can occur in any part of the human body[3]. SFT is difficult to diagnose clinically as the histological changes in SFT are complex and diverse, making it difficult to distinguish SFT from other tumors. Currently, the diagnosis of SFT mainly relies on imaging studies and pathological examinations.

An SFT on computed tomography (CT) mostly presents as a round, well-defined and isolated mass without lobules or shallow lobules that are significantly associated with benign or malignant tumors[4]. Calcification may be present in the tumor, with the solid area being generally uniform in density, but with the cystic lesion area being generally low in density. Invasive or malignant SFT is prone to necrosis, hemorrhage and degeneration that lead to a relatively mixed CT density. Typical CT manifestations of most SFTs appear to be nodular or patchy, with sporadic calcification in slightly low-density areas that may exist in equally high- or slightly high-density areas[5,6]. Different tumor tissues exhibit different signals during MRI. A number of studies have reported that T1 weighted imaging (T1WI) can show low or isosignals, while T2 weighted imaging (T2WI) can show low or medium signals, or a mixture of low and high signals. For instance, long T1 and long T2 signals have been observed in cystic degeneration, and if the tumor contains a large amount of fibrous tissue, T1WI and T2WI signals are low. Contrast-enhanced scanning of the tumor can result in the tumor being moderately or significantly enhanced[2,5,7].

Head and neck SFTs can be challenging to distinguish from neurilemmoma, cavernous hemangioma, pleomorphic adenoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma and other diseases[2]. Typically, MRI scans of schwannoma show T1WI with low or isosignals and T2WI with high or slightly high signals; while those of atypical schwannoma show uneven T1WI and T2WI[8]. The main features of schwannoma on MRI scans can be summarized as follows: (1) Target sign: The central region and the edge region on T1WI show a medium signal and low signal, respectively; while the central region and the edge region on T2WI show an uneven signal and high signal, respectively[9]; (2) Nerve access sign: The main occurrence of tumors is in the large intermuscular nerve trunk; (3) Fat encapsulation and fatty tail sign: Fat encapsulation around the tumor is clearly shown on T1WI; and (4) Cerebrospinal fluid is present in the caudate[10]. Our patient had a clear boundary between the right parapharyngeal gland tumor and the right parotid gland tumor, and a connection was found between the tumors in the right parapharyngeal space. Therefore, the mass was considered to be a single dumbbell-shaped tumor that compressed the right parotid gland in the parapharyngeal space (Figure 3). MRI scans showed that the right parotid tumor was a T1 long T2 signal mass with a clear boundary. Irregular T1 and slightly longer T2 signal masses with clear boundaries were seen in the center of the right parapharyngeal space. On the contrary, imaging findings revealed the fatty inclusion sign of a schwannoma (Figure 3), possibly due to the diversity and complexity of SFT tumor tissues. However, accurate diagnosis of SFT requires further postoperative pathological and immunohistochemical examinations.

In terms of pathological features, SFT cells have alternately arranged sparse and dense areas. The sparse areas mainly comprise fine spindle cells with insignificant heteromorphism. The cells in the rich area are mainly oval, round and short fusiform, with less cytoplasm, vacuolated nuclei and rare mitosis events. The cells can be arranged radially, mat striated, in bundles or in the shape of a fishbone. Intercellular collagen fibers of varying thickness and morphology as well as a large number of parenchymal blood vessels are often found in SFT. A few SFTs can have cystic changes and mucous changes. Due to the current lack of a unified standard method for the diagnosis of malignant SFT, most recognized malignant SFT cells are characterized by the presence of high tumor cell density, obvious atypia, mitotic phase count of ≥ 4/10 HPF, necrosis and hemorrhage[11,12]. In addition to pathomorphological analysis, immunohistochemistry evaluation is also important for the accurate diagnosis of SFT. SFT-positive immunohistochemical markers mainly include vimentin, CD34, CD99 and Bcl-2. A study showed that the widely distributed and strongly expressed CD34 is a specific marker for SFT[13]. Another study demonstrated that SFT cells have a CD99-positive rate of approximately 70% and a Bcl-2-positive rate of about 35%[13,14]. However, Bcl-2 has been found to be more sensitive than CD34 in the diagnosis of malignant SFT[15]. Liu et al[16] have also indicated that CD34 expression can be decreased or lost in the mesogenetic region of SFT cells. Compared with tumors that share similar morphological characteristics and immunohistochemical expression to SFTs, it is difficult to diagnose accurately SFT through the joint application of immunohisto-chemical antibodies such as CD34, CD99, Bcl-2 and vimentin. Researchers subsequently found that STAT6 expression is more specific in the diagnosis of SFT[17]. Yoshida et al[18] conducted immunohistochemical staining of STAT6 in 49 patients with SFT and 159 patients with non-SFT tumors, and the results showed that the 49 patients with SFT all displayed STAT6 prokaryotic expression, which was absent in more than 95% of patients with non-SFT tumors. Cheah et al[19] carried out immunohistochemical staining with RabMab antibody STAT6 on 54 patients with SFT and 99 patients with non-SFT tumors which share similar cytohistologic characteristics with SFT, and concluded that all 54 patients with SFT had positive expression of STAT6 in the nucleus, while 99 patients with non-SFT tumors all had negative expression of STAT6 in the nucleus. The above studies confirm that STAT6 is an immunohistochemical marker highly specific for SFT. The immunohistochemical evaluation of our patient showed results consistent with those for SFT diagnosis.

In terms of treatment methods, complete surgical resection is the main treatment approach. The tumors should be clearly distinguished from surrounding tissues as quickly as possible. SFT recurrence depends on whether the tumor has been completely removed during surgery[20]. As these tumors were unable to be clearly defined as benign or malignant before and during surgery, Zhu et al[21] have suggested that the resection range of SFT should be ≥ 2 cm from normal tissues. If the tumor is infiltrating or metastasizing, the scope of surgery should be expanded. For patients with incomplete removal and extensive tumor invasion, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy can be used to reduce the rate of recurrence. Malignant transformation of SFT in the head and neck is relatively rare[22]. SFT from pleural tissues that occurs in the abdominal cavity is more invasive with a higher recurrence rate and a worse prognosis compared to that from other areas[23]. Therefore, regular postoperative follow-up is very important.

We report a rare dumbbell-shaped parapharyngeal space SFT. Currently, the diagnosis of such diseases mainly relies on imaging and pathological examinations, but this case indirectly shows that preoperative imaging evaluation could lead to misdiagnosis of a non-typical SFT, and confirmation relies on postoperative pathological immunohisto-chemical results. As it is difficult to determine whether a tumor is benign or malignant before and during surgery, thorough tumor resection is necessary. We fully removed the tumor to avoid recurrence.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Urabe M S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Zhou Y, Chu X, Yi Y, Tong L, Dai Y. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor in retroperitoneum: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Qian W, Hu H, Ma G, Su GY, Xu XQ, Shi HB, Wu FW. CT and MRI feature of solitary fibrous tumor in head and neck region. Zhongguo Yixue Yingxiang Jishu. 2017;33:1744-1745. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Chan JK. Solitary fibrous tumour--everywhere, and a diagnosis in vogue. Histopathology. 1997;31:568-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Milenkovic BA, Stojsic J, Motohiko A, Dudvarski A, Jakovic R, Stevic R, Ercegovac M. Solitary fibrous pleural tumor associated with loss of consciousness due to hypoglycemia. Med Oncol. 2009;26:131-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jiao YC, Ding X, Yang HB. Solitary fibrous tumors in the head and neck: a report of 5 cases. Shiyong Zhongliu Zazhi. 2014;29:345-348. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Mao ZQ, Xiao XZ, Wang MJ. Imaging Diagnosis and Pathological Analysis of Solitary Fibrous Tumors. Jiangxi Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2007;47:63-66. |

| 7. | Tateishi U, Nishihara H, Morikawa T, Miyasaka K. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: MR appearance and enhancement pattern. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiu ZG, Lv FJ, Chen LP. Multivariater analysis of MRI imaging diagnosis of schwannoma. Chengdu Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2020;15:486-494. |

| 9. | Shi FX, Liu JB, Guo YQ. Diagnostic Value of 3.0 T MRI in Nerve Sheath Tumor of Extremities: Report of 12 Cases. Linchuang Fangshe Xue Zazhi. 2013;32:703-707. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Ding XN, Yuan JH, Wang ZP. CT and MRI Features of Peripheral Neurilemoma. Fangshe Xue Shijian. 2009;24:305-308. |

| 11. | Tanaka M, Sawai H, Okada Y, Yamamoto M, Funahashi H, Hayakawa T, Takeyama H, Manabe T. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor originating from the peritoneum and review of the literature. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CS95-CS98. [PubMed] |

| 12. | England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640-658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Ma J, Du J, Zhang Z, Wang H, Wang J. Synchronous primary triple carcinoma of thyroid and kidney accompanied by solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: a unique case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4268-4273. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ronchi A, Cozzolino I, Zito Marino F, Accardo M, Montella M, Panarese I, Roccuzzo G, Toni G, Franco R, De Chiara A. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: A distinct entity from pleural solitary fibrous tumor. An update on clinical, molecular and diagnostic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;34:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bishop JA, Rekhtman N, Chun J, Wakely PE Jr, Ali SZ. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor: cytopathologic findings and differential diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu TY, Zhong L. Clinicopathological analysis of malignant solitary fibrous tumor and literature review. Xiandai Zhongliu Yixue. 2020;28:635-638. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, Mertens F, Hornick JL. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:390-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Narita Y, Kawai A, Asamura H, Kushima R. STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:552-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheah AL, Billings SD, Goldblum JR, Carver P, Tanas MZ, Rubin BP. STAT6 rabbit monoclonal antibody is a robust diagnostic tool for the distinction of solitary fibrous tumour from its mimics. Pathology. 2014;46:389-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Insabato L, Siano M, Somma A, Gentile R, Santangelo M, Pettinato G. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:250-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhu L, Lin L, GUO DW. Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Solitary Fibrous Tumour. Zhongguo Puwai Jichu Yu Linchuang Zazhi. 2012;19:99-101. |

| 22. | Cox DP, Daniels T, Jordan RC. Solitary fibrous tumor of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cranshaw IM, Gikas PD, Fisher C, Thway K, Thomas JM, Hayes AJ. Clinical outcomes of extra-thoracic solitary fibrous tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:994-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |