Published online Feb 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1196

Peer-review started: October 27, 2020

First decision: November 26, 2020

Revised: December 9, 2020

Accepted: December 22, 2020

Article in press: December 22, 2020

Published online: February 16, 2021

Processing time: 94 Days and 18.3 Hours

Autoimmune antibodies are detected in many diseases. Viral infections are accompanied by several immunopathological manifestations. Some autoimmune antibodies have been associated with the immune response induced by virus or drugs. Thus, a comprehensive diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B combined with autoimmune hepatitis is required, and immunosuppressant or antiviral therapy should be carefully considered.

We present a case of a patient who had negative transformation of autoimmune antibodies during chronic active hepatitis B. A 50-year-old female who had a history of asymptomatic hepatitis B virus carriers for more than 10 years presented to the hospital with the complaint of weakness for 1 wk. Blood tests revealed elevated liver enzymes; the detection of autoantibodies was positive. Hepatitis B viral load was 72100000 IU/mL. The patient started tenofovir alafenamide fumigate 25 mg daily. Liver biopsy was performed, which was consistent with chronic active hepatitis B. The final diagnosis of the case was chronic active hepatitis B. The autoimmune antibodies turned negative after 4 wk of antiviral therapy. The patient recovered and was discharged with normal liver function. There was no appearance of autoantibodies, and liver function was normal at regular follow-ups.

Autoimmune antibodies may appear in patients with chronic active hepatitis. It is necessary to differentiate the diagnosis with autoimmune hepatitis.

Core Tip: This case involved dynamic changes in autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B. The patient showed positive hepatitis B surface antigen, which can cause an autoimmune phenomenon during the clearance of hepatitis B virus (HBV). Liver pathology was performed to differentiate from autoimmune hepatitis. It is possible that the virus has a role in inducing immune responses in HBV infection. This is closely related to hepatocyte injury caused by HBV infection, which is mainly mediated by immunity. Autoantibodies can appear during viral hepatitis, and the combination of liver pathology and dynamic monitoring is required.

- Citation: Zhang X, Xie QX, Zhao DM. Negative conversion of autoantibody profile in chronic hepatitis B: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(5): 1196-1203

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i5/1196.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1196

Host immune responses induced by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection substantially drive disease progression and significantly influence the efficacy of antiviral treatments in HBV-infected individuals. Some studies have shown that non-virus-specific inflammatory cells within the liver may also actively participate in HBV-associated liver pathogenesis.

We report a case of autoimmune antibody transformation from positive to negative during the course of HBV and refer to the relevant literature to explain the related reasons for the dynamic changes in these autoantibodies. Liver pathology can help diagnosis and differentiate between viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), which plays an important role in the treatment strategy.

AIH may have an association with some pathogens[1]. Although a few investigations associated with autoantibody positivity in patients with chronic hepatitis C have been reported, autoantibody positivity in patients with chronic hepatitis B are rare in the literature[2]. In this case, the antinuclear antibody (ANA) profile included anti-SSA antibody, anti-SSB antibody, anti-liver/kidney microsomal-1 antibody (LKM-1) and anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antibodies in a patient with chronic hepatitis B became negative during the clearance of HBV.

A 50-year-old female who had a history of positive hepatitis B surface antigen for more than 10 years presented to The Infectious Department of our hospital complaining of aggravating anorexia and fatigue. During her presentation in The Infectious Department, she had nausea and vomit symptoms.

The patient’s symptoms started a week ago with gradually increasing gastrointestinal symptoms including anorexia and nausea. Her liver function tests showed elevated transaminases.

She had a past medical history of being a carrier of HBV for more than 10 years without antiviral treatment. She had no cardiac function abnormalities, arterial hypertension or diabetes mellitus. She had no negative drug history, and no alcohol intake.

The patient reported that her four siblings were infected with HBV, her mother died from hepatocellular carcinoma, and her father was in good physical condition.

After admission, the patient’s temperature was 36.6 °C, heart rate was 91 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 145/104 mmHg and oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. The patient was 160 cm tall and weighed 53 kg. The clinical examination revealed light scleral icterus without any other pathological signs.

Laboratory values on admission and during hospitalization are shown in Table 1. A series of tests were performed after admission to The Infectious Disease Department. Blood analysis revealed the following: Alanine aminotransferase, 575 U/L; Aspartate aminotransferase, 593 U/L; Total bilirubin, 108.3 μmol/L; Alkaline phosphatase 116 IU/L; Positive hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-LKM-1 > 1:80; Positive anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas; Positive anti-mitochondrial antibody; and Positive anti-SSA antibody and anti-SSB antibody.

| Parameters | Day 1 | Day 7 | Day 15 | Day 25 | 2 mo | Reference ranges |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 3.05 | 4.18 | 4.93 | 3.76 | 556 | 3.5-9.5 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 101 | 93 | 102 | 112 | 216 | 125-350 |

| AST (U/L) | 593 | 224 | 75 | 28 | 34 | 0-34 |

| ALT (U/L) | 575 | 266 | 89 | 26 | 28 | 0-49 |

| ALP (U/L) | 112 | 132 | 116 | 79 | 76 | 45-129 |

| GGT (U/L) | 58 | 134 | 113 | 55 | 36 | 0-38 |

| LDH (U/L) | 267 | 208 | 159 | 159 | 221 | 120-246 |

| ALB (g/L) | 34.8 | 34.3 | 28.9 | 33.7 | 27.8 | 35.0-53.0 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 38.30 | 45.90 | 108.30 | 51.45 | 11.30 | 5.00-21.00 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 22.50 | 33.20 | 84.92 | 37.37 | 8.09 | 0-6.80 |

| HBV-DNA (copies/mL) | 7.21 × 108 | 1.62 × 104 | ≤ 500 | ≤ 500 | ||

| HBsAg (IU/mL) | > 52000 | 3373 | 135 | < 0.05 | ||

| ANA | < 1:80 | < 1:80 | < 1:80 | Negative (< 1:80) | ||

| Anti-SM (RU/mL) | 41.17 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | ||

| Anti-SS-A (RU/mL) | 42.70 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | ||

| Anti-SS-B (RU/mL) | 176.31 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | ||

| CENTRO (RU/mL) | 39.59 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | ||

| AMA-M2 (RU/mL) | 19.99 | 25.87 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |

| LKM-1 (RU/mL) | 223.38 | > 400 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |

| SLA/LP (RU/mL) | 39.61 | 43.04 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |

| SP100 (RU/mL) | 16.26 | 20.59 | < 20 | < 20 | < 20 | |

| Anti-HCV | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | ||

| HAV-IgM | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | ||

| HEV-IgM | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | ||

| Anti-HIV | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

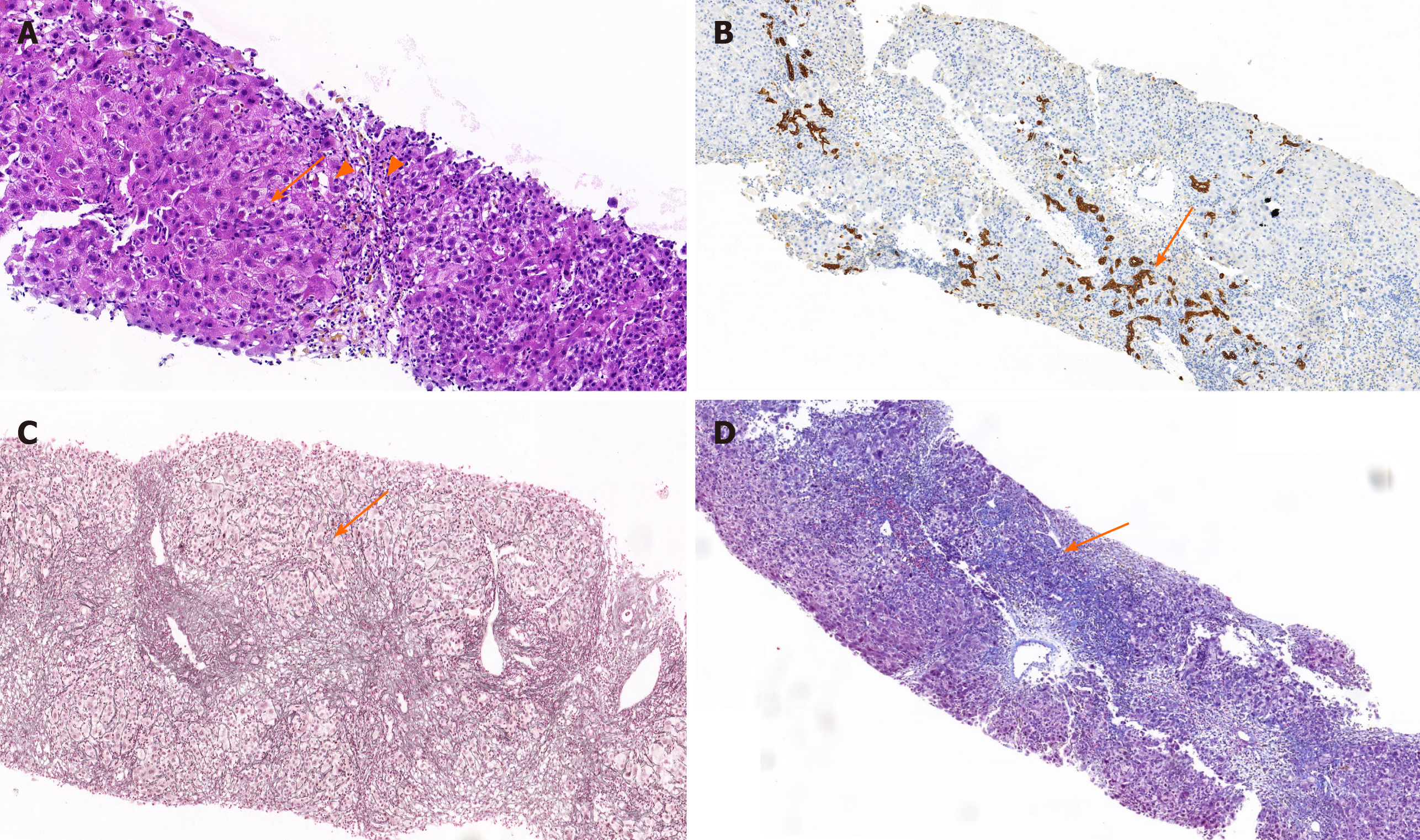

The hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver tissue: The structure of hepatic lobules is unclear. The hematoxylin and eosin staining showed varying degrees of hepatocyte edema with moderate to severe piecemeal necrosis and scattered eosinophilic bodies (Figure 1A, arrows). Small bile duct in the portal area was accompanied by lymphocyte-predominant inflammation with a small amount of eosinophil infiltration (Figure 1A, filled triangles).

Immunohistochemistry analysis of liver tissue: The proliferation of small bile ducts in the portal area were obvious (Figure 1B, arrows), with more infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells and positive marker detection including hepatitis B surface antigen (+), HBcAg (+-), bile duct epithelium (CK19+), IgG (+), and IgG4 (-) combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Findings were consistent with mild chronic hepatitis compatible with HBV infection, without histological stigmata of autoimmunity (Figure 1B).

Mesh fiber staining of liver tissue: The reticular fiber staining showed that the hepatic lobular stent was significantly damaged (Figure 1C, arrows). The characteristic floral ring structure of AIH was not seen (Figure 1C).

Masson staining of liver tissue: The portal area was enlarged with fibrosis, the formation of bridging fiber band was visible in the focal area, and collagen fiber proliferated in the portal area by Masson staining (Figure 1D, arrows).

Chronic active hepatitis B (pathological grade and stage: G3S3).

The patient, following her clinical manifestations and laboratory tests in our department, was started on tenofovir alafenamide fumigate 25 mg QD orally without corticosteroids. Other transfusion treatment including compound magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate and reduced glutathione was used for more than 20 d until nucleic acid testing was performed, and autoantibodies were found to be positive and liver biopsy was performed. According to the pathology of hepatic tissue, it did not meet the diagnostic criteria of AIH. Blood work showed completely normal liver enzymes and decreased HBV viral load.

The comprehensive medical treatment was successfully accomplished by improving liver function and antiviral therapy with tenofovir alafenamide fumarate tablets 25 mg QD orally during hospitalization and follow-up (at least 5 years). The process of liver puncture was accomplished smoothly. The antiviral effect was remarkable, and liver enzymes levels dropped significantly (Table 1). Some positive markers were retested, and the markers of AIH were negative (Table 1). The patient recovered well and was discharged from the hospital 25 d after the treatment. At a follow-up visit, 12 wk later (2 mo after hospital discharge), the patient was asymptomatic, there was no appearance of autoantibodies, and liver function was normal (Table 1). The patient continued to take the antiviral drug and maintained regular follow ups every 6 mo for 5 years.

Autoantibodies can be detected in patients with chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection. Acay et al[3] reported that 67 patients with chronic hepatitis B who had a positive ANA rate was 12%. Many cases reports have shown that autoimmune markers can be detected in patients with hepatitis C[4]. Other hepatitis viruses like hepatitis A or hepatitis E can also act as triggers of autoimmune phenomena or diseases[5]. Some studies have shown that autoimmune markers were identified in adult patients[6]. HBV infection has been presented with circulating non-organ-specific autoantibodies associated to a variety of immunopathological manifestations[7]. This included smooth muscle antibody, ANA and anti-LKM1[8]. The serologic autoimmune phenomenon was also reported in patients who had received treatment with interferon[9]. At present, the role of immune factors in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B has been widely recognized[10]. A cohort study was conducted to study the detection of autoantibodies in patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B. The result showed that low level titers of antibodies were detected in 8 of 47 patients (17%) with treatment-naive, histologically proven chronic hepatitis B[11]. Another study showed a similar positive rate in chronic hepatitis B or C[3]. This may indicate some interaction mechanisms occur during the period of immunity elimination. Some researchers have indicated that there is more than a single mechanism responsible for viral autoimmunity[12]. It was shown that viral hepatitis such as hepatitis A virus, hepatitis C virus or hepatitis E virus may have triggered an autoimmune response in many cases[13].

However, detection of autoantibodies in chronic liver disease does not necessarily indicate a diagnosis of AIH. The presence of a homogenous pattern of antibodies may be more relevant. It is believed that there are many kinds of specific autoantibodies in patients with AIH[14,15]. The characteristic of AIH is the presence of interface hepatitis, which shows inflammation of hepatocytes at the junction of the portal tract and hepatic parenchyma. According to the simplified criteria for AIH diagnosis, hepatocellular rosette formation is a typical histological feature of AIH[16]. Although the precise mechanisms of AIH are unknown, environmental factors may trigger disease onset in genetically predisposed individuals.

Several observations in many cases suggest that an extractable nuclear antigen antibody profile was prevalent in patients with chronic hepatitis B, and it was strongly correlated with both compensated and decompensated cirrhosis[17]. Liver biopsy was carried out showing signs of severe fragmented necrosis and fibrogenesis, and lymphocyte and plasmocyte infiltrations were observed. Based on a simplified diagnostic scoring system for AIH[18], AIH is generally divided into type 1 (AIH-1) and type 2 (AIH-2). The autoantibodies related to AIH-1 mainly include ANA, anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas and anti-neutrophil antibody; the autoantibodies related to AIH-2 mainly include anti-LKM antibody and anti-liver cytosol type 1[19]. The appearance of autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of chronic HBV infection is also one of the manifestations of autoimmune disorders[20]. In general, the human immune system starts to recognize antigens and gradually produces increasing affinity of the relevant antibody after antigen exposure[21]. T follicular helper cells can be over the augmented capacity to help B cells for antibody secretion, which can induce liver inflammation and the production of antibodies in extrahepatic manifestations[22].

In the 1980s, some studies showed that glucocorticosteroid pretreatment therapy can clear the makers of viral replication in patients with chronic HBV infection[23], but in a large trial, the glucocorticosteroid did not indicate any beneficial effect of prednisone pretreatment[24]. It is recommended that antiviral drugs are the major therapy for chronic active hepatitis B based on the current guidelines[25]. Our case showed that the antibody titers vary from gradually decreased to disappeared along with treatment (Table 1). This also reminded us that an autoantibody is not a specific marker for the diagnosis during autoimmune liver diseases. Some specific antibodies can also be found in patients with viral hepatitis, drug-related hepatitis and alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The effect of steroids is unclear in such cases; thus, treatment with steroids should be delayed until HBV is appropriately suppressed.

There is likely a role for induced immune responses with chronic HBV and hepatitis C virus infection. One generally accepted hypothesis is that the molecular stimulation between exogenous antigens and autoantigens leads to the destruction of immune tolerance. The most reported association between hepatitis and AIH is documented for chronic hepatitis C virus[26]. Gregorio et al[27] observed that the majority of patients infected with hepatitis C virus generated smooth muscle antibody or ANA, which reacted to mimicking molecular mimicry of amino acid sequences between regions of the hepatitis C virus polyprotein and regions of some smooth muscle proteins. We think that the dynamic change of autoantibodies indicates that an immune reaction occurs in the process of spontaneous clearance of HBV[28].

Some autoimmune pathological processes are accompanied by liver inflammation. Although autoantibodies were initially positive in our patient, detection of autoantibodies in chronic liver disease did not necessarily indicate a diagnosis of AIH, likely because of an autoimmune interaction and the production of a variety of heterophile antibodies during the course of the immune response. There are theories suggesting that some interaction mechanisms and immune responses occur during the period of chronic active HBV infection.

We greatly appreciate the patient, her family and the medical staff involved in this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mohammed RHA, Said ZNA, Volynets GV S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Christen U, Hintermann E. Pathogens and autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;195:35-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune manifestations in viral hepatitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:73-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Acay A, Demir K, Asik G, Tunay H, Acarturk G. Assessment of the Frequency of Autoantibodies in Chronic Viral Hepatitis. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:150-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cacciato V, Casagrande E, Bodini G, Furnari M, Marabotto E, Grillo F, Giannini EG. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection disclosing a previously hidden, underlying autoimmune hepatitis: Autoimmune hepatitis and HCV. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Ripellino P, Gobbi C, Cerny A, Baserga A, Di Bartolomeo C, Bihl F, Deleonardi G, Melidona L, Grondona AG, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Muratori L; Swiss Autoimmune Hepatitis Cohort Study Group. Autoimmune liver disease serology in acute hepatitis E virus infection. J Autoimmun. 2018;94:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shepherd SM, Lyon WK. Gingival bleeding: initial presentation of prostatic cancer. J Fam Pract. 1990;30:98-100. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Maya R, Gershwin ME, Shoenfeld Y. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and autoimmune disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008;34:85-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gregorio GV, Jones H, Choudhuri K, Vegnente A, Bortolotti F, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Autoantibody prevalence in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: effect in interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1996;24:520-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iijima Y, Kato T, Miyakawa H, Ogino M, Mizuno M, Sugihara K, Ando T, Fujiwara K, Orito E, Ueda R, Mizokami M. Effect of interferon therapy on Japanese chronic hepatitis C virus patients with anti-liver/kidney microsome autoantibody type 1. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:782-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tseng TC, Huang LR. Immunopathogenesis of Hepatitis B Virus. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:S765-S770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Şener AG, Aydın N, Ceylan C, Kırdar S. [Investigation of antinuclear antibodies in chronic hepatitis B patients]. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2018;52:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sener AG, Afsar I. Infection and autoimmune disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3331-3338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel I, Ching Companioni R, Bansal R, Vyas N, Catalano C, Aron J, Walfish A. Acute hepatitis E presenting with clinical feature of autoimmune hepatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:33342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sebode M, Weiler-Normann C, Liwinski T, Schramm C. Autoantibodies in Autoimmune Liver Disease-Clinical and Diagnostic Relevance. Front Immunol. 2018;9:609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Czaja AJ. Autoantibodies in autoimmune liver disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2005;40:127-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gurung A, Assis DN, McCarty TR, Mitchell KA, Boyer JL, Jain D. Histologic features of autoimmune hepatitis: a critical appraisal. Hum Pathol. 2018;82:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lin XQ, Sheng L, Xiao X, Wang QX, Miao Q, Guo CJ, Hua J, Ma X. [Analysis of clinical diagnosis and treatment in chronic hepatitis B combined with autoimmune hepatitis]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020;28:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, Bianchi FB, Shibata M, Schramm C, Eisenmann de Torres B, Galle PR, McFarlane I, Dienes HP, Lohse AW; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1252] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69:394-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 69.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Song H, Tan G, Yang Y, Cui A, Li H, Li T, Wu Z, Yang M, Lv G, Chi X, Niu J, Zhu K, Crispe IN, Su L, Tu Z. Hepatitis B Virus-Induced Imbalance of Inflammatory and Antiviral Signaling by Differential Phosphorylation of STAT1 in Human Monocytes. J Immunol. 2019;202:2266-2275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bolstad N, Warren DJ, Nustad K. Heterophilic antibody interference in immunometric assays. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:647-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lei Y, Hu T, Song X, Nie H, Chen M, Chen W, Zhou Z, Zhang D, Hu H, Hu P, Ren H. Production of Autoantibodies in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection Is Associated with the Augmented Function of Blood CXCR5+CD4+ T Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Weller IV, Bassendine MF, Murray AK, Craxi A, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Effects of prednisolone/azathioprine in chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Gut. 1982;23:650-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Perrillo RP, Schiff ER, Davis GL, Bodenheimer HC Jr, Lindsay K, Payne J, Dienstag JL, O'Brien C, Tamburro C, Jacobson IM, Sampliner R, Feit D, Lefkowitch J, Kuhns M, Meschievitz C, Sanghvi B, Albrecht J, Gibas A; Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. A randomized, controlled trial of interferon alfa-2b alone and after prednisone withdrawal for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. The Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Idilman R. The summarized of EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Marconcini ML, Fayad L, Shiozawa MB, Dantas-Correa EB, Lucca Schiavon Ld, Narciso-Schiavon JL. Autoantibody profile in individuals with chronic hepatitis C. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gregorio GV, Choudhuri K, Ma Y, Pensati P, Iorio R, Grant P, Garson J, Bogdanos DP, Vegnente A, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Mimicry between the hepatitis C virus polyprotein and antigenic targets of nuclear and smooth muscle antibodies in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:404-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang Z, Zhang JY, Wang LF, Wang FS. Immunopathogenesis and prognostic immune markers of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |