Published online Feb 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1127

Peer-review started: September 2, 2020

First decision: November 26, 2020

Revised: December 9, 2020

Accepted: December 16, 2020

Article in press: December 16, 2020

Published online: February 16, 2021

Processing time: 150 Days and 3.8 Hours

This study describes the use of a moisture chamber to treat corneal ulceration due to temporary lagophthalmos in a critically ill patient.

A 46-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit after a car accident. She suffered multiple injuries that included brain injury and presented with moderately decreased consciousness and lagophthalmos in her right eye. Within 6 d, her consciousness improved considerably; at which time, exposure keratopathy occurred and worsened to corneal ulceration. Lubricating gel, antibiotic ointment, and bandage contact lens were all ineffective in preventing or treating the exposure keratopathy. Instead of tarsorrhaphy, a moisture chamber was applied which successfully controlled the corneal ulceration. The moisture chamber was discontinued when complete eyelid closure recovered a week later.

A moisture chamber may be an effective, noninvasive alternative to tarsorrhaphy for treating severe exposure keratopathy due to temporary lagophthalmos.

Core Tip: Moisture chambers, including moisture chamber spectacles, swimming goggles, and polyethylene covers that cover the area from the eyebrow to the cheek, act as barriers against tear evaporation and provide direct protection of the ocular surface. Here, we report a 46-year-old woman with lagophthalmos in her right eye treated with a moisture chamber, who suffered a brain injury after a car accident. Use of the moisture chamber successfully controlled the corneal ulceration.

- Citation: Yu XY, Xue LY, Zhou Y, Shen J, Yin L. Management of corneal ulceration with a moisture chamber due to temporary lagophthalmos in a brain injury patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(5): 1127-1131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i5/1127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i5.1127

Preventative protocols and treatment choices for exposure keratopathy in the intensive care unit (ICU) are not the same as those in the ophthalmic department. Except for those with pre-existing eye abnormalities or facial trauma, most critically ill patients who suffer from lagophthalmos are under heavy sedation or have impaired consciousness, and are therefore unable to report ophthalmologic complaints[1]. ICU medical and nursing staff are naturally preoccupied with stabilizing vital signs and organ function. Therefore, it is essential for eye care measures to be effective, easy to apply, time saving, compatible with pupil examination, and acceptable to both staff and patients’ family members. Compared with other interventions that solve life-threatening problems, there is much less evidence available to support the choice of an optimal eye-care modality to prevent or cure exposure keratopathy in critically ill patients.

A 46-year-old woman was admitted to the ICU after a car accident. She suffered multiple injuries, including right frontotemporal lobe and left temporal lobe contusion and laceration, right frontotemporal cranial bone fracture, bilateral orbital fractures, pulmonary contusion, and right tibiofibula fracture with displacement, which was treated with external fixation in the emergency department. The injuries caused rhabdomyolysis.

The patient was without significant medical history.

The patient was without significant medical history.

The family history was unremarkable.

She was comatose with a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 9, which measured eye response (1 point), verbal response (3 points), and motor response (5 points). Pupils were equally reactive. There was lagophthalmos (7 mm) in the right eye without Bell’s phenomenon.

The laboratory examinations were unremarkable.

The imaging examinations are described in the treatment section.

The patient was diagnosed with an exposed cornea in the right eye.

Continuous infusion of intravenous sufentanil and dexmedetomidine were given to relieve agitation. Both eyes received daily cleansing with sterile water. A 2-cm strip of carbomer gel (Liposic; Dr. Gerhard Mann, Chem.-pharm. Fabrik GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was instilled in the right eye every 6 h.

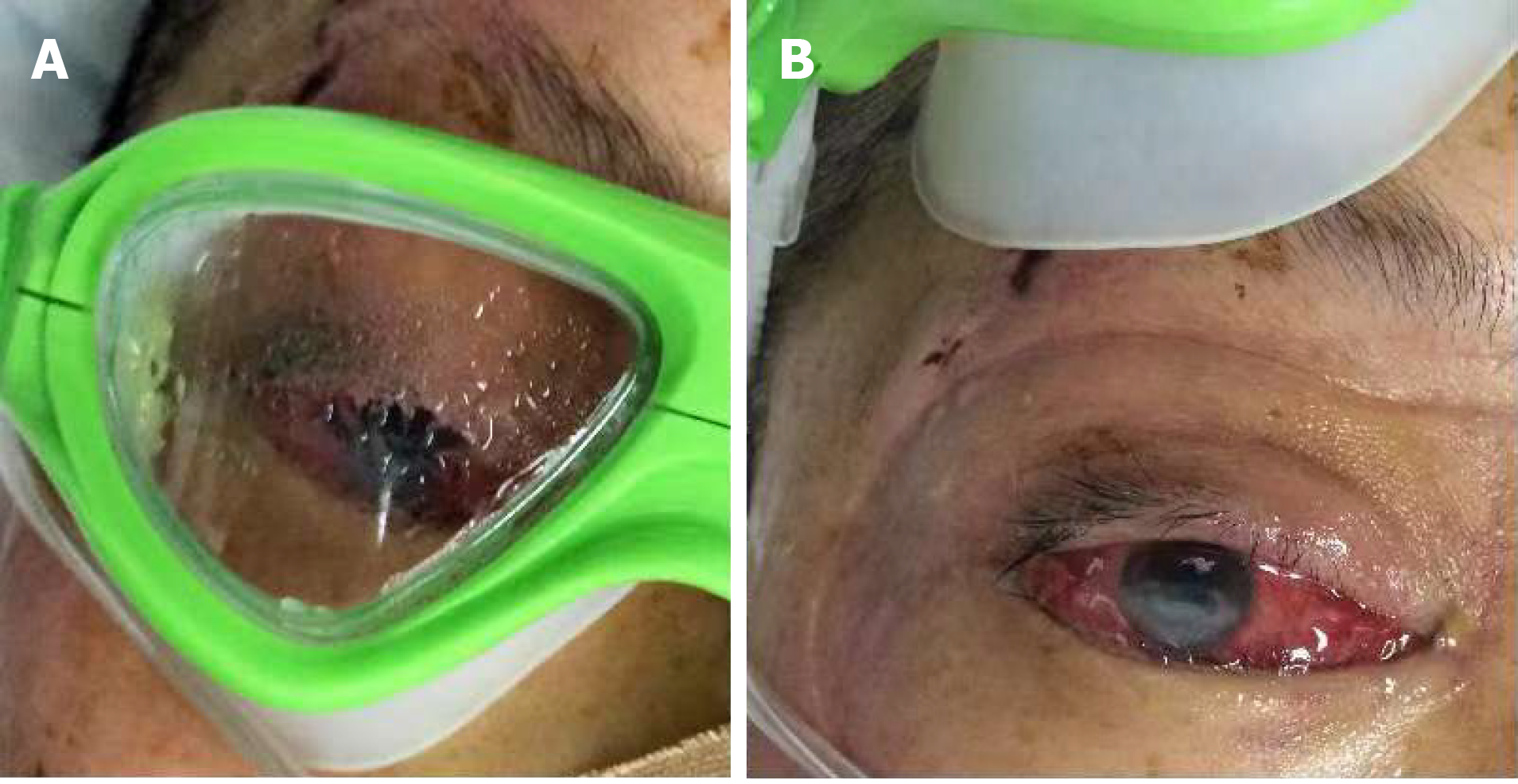

On the 3rd ICU day, conjunctival congestion and mild chemosis occurred in the right eye. The carbomer gel was replaced with ofloxacin ointment. On day 5, the patient’s level of consciousness improved to a GCS score of 12, which measured eye response (3 points), verbal response (3 points), and motor response (6 points). However, heavy chemosis with dellen formation and corneal opacity involving the inferior third of the cornea occurred in the right eye. It was then observed that in the ICU environment (temperature: 22.5-25.5°C, humidity: 50%-60%), a 2-cm strip of carbomer gel or ofloxacin ointment could maintain the patient’s corneal wetting for approximately 1-1.5 h (Figure 1). A consulting ophthalmologist made a diagnosis of corneal ulceration and inserted a bandage contact lens (BCL; PureVision Extended Wear; Bausch and Lomb Inc., Rochester, NY, United States). Levofloxacin drops were placed in the right eye every 6 h. The patient regained consciousness the next day with a GCS score of 14, which measured eye response (4 points), verbal response (4 points), and motor response (6 points), but the contact lens dislodged. The conjunctiva prolapsed through the palpebral aperture, and corneal opacity involved the inferior 40% of the cornea. Visual acuity was hand motion. The consulting ophthalmologist suggested tarsorrhaphy, but we decided to apply a moisture chamber. The patient’s family, who refused to cover her eye with plastic wrap (polyethylene cover), consented to apply swimming goggles. A drop of ofloxacin ointment was placed in the right eye every 6 h. The corneal ulcer was under control on day 7 (Figure 2).

Moisture chamber therapy was discontinued on day 13 when complete eyelid closure recovered. Visual acuity was counting fingers at 2 m. After discharge from the ICU, the patient continued using levofloxacin drops 4 times per day and ofloxacin ointment at night for 5 wk. When she was reevaluated 6 mo later, ocular findings were normal except for corneal nebula involving the inferior 40% of the right cornea. Uncorrected visual acuity was 20/25, and best corrected visual acuity was 20/20.

The results of a recent meta-analysis suggested that moisture chambers were more effective at corneal protection in critically ill patients than lubricating eye drops and similar in effectiveness to lubricating ointments[2]. In the randomized controlled trials included in that meta-analysis, ointments were applied every 2-6 h. Accordingly, we chose lubricating gel to prevent and antibiotic ointment to treat exposure keratopathy, but neither was effective as applying these lubricants every 6 h could not prevent corneal dryness in this patient in our ICU environment. Aggressive hourly lubrication with gel or ointment may be able to prevent or cure exposure keratopathy. However, this significantly increases the workload of nursing staff, and may be omitted if there are other interventions with greater priority.

A randomized pilot trial suggested that BCLs and punctal plugs were more effective than ocular lubrication (lubricating drops 4 times daily plus ointment 3 times daily) in limiting exposure keratopathy in critically ill patients[3]. The BCLs and the punctal plugs in this study were all inserted by an ophthalmologist. It can be difficult for ICU staff without specific training to insert or remove a BCL. If the lens dislodges, a thorough eye examination performed by an ophthalmologist may be needed to reliably rule out folded lens retention in the eye. These also increase staff workload. Extended-wear soft contact lenses carry a risk of infectious keratitis[4,5]. It was noted that working in hospital environments increased microbiological contamination of BCLs[6]. Therefore, ICU patients wearing BCLs may have a higher risk of corneal infection. Punctal plug insertion helps to preserve aqueous and artificial tears on the ocular surface but does not prevent evaporation of tears or provide direct protection of the cornea. Spontaneous plug loss is a frequent complication, occurring in 40% of patients on average[7], and it is difficult for ICU staff to detect whether the plug is in situ. For this patient, the active ocular infection contraindicated punctal plug placement.

Tarsorrhaphy, an invasive procedure, is suggested in extreme cases. It interferes with pupil examination and makes delivering eye treatment difficult. In addition, there is a risk of silent infections[8]. Severe exposure keratopathy in this patient was an indication for tarsorrhaphy, but a noninvasive treatment was preferred. Choosing an appropriate treatment for exposure keratopathy depends not only on the severity of lagophthalmos but also on the potential for recovery. GCS score is one of the predictive factors for exposure keratopathy[9]. As the patient’s GCS score increased rapidly within a week, this indicated that eyelid closure would probably recover soon.

Moisture chambers (including moisture chamber spectacles, swimming goggles, and polyethylene covers that cover the area from the eyebrow to the cheek) act as barriers against tear evaporation and provide direct protection of the ocular surface. It was reported that moisture chambers increase the periocular humidity and tear-film lipid-layer thickness[10,11], which may reduce lubricant use and thus be a time-saving measure.

This report describes the use of a moisture chamber to manage corneal ulceration due to temporary lagophthalmos in the ICU. Moisture chambers are inexpensive, require minimal training, and place a low demand on nursing care. As an alternative to tarsorrhaphy, this noninvasive procedure may effectively treat severe exposure keratopathy in critically ill patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical Care Medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigues AT S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kousha O, Kousha Z, Paddle J. Exposure keratopathy: Incidence, risk factors and impact of protocolised care on exposure keratopathy in critically ill adults. J Crit Care. 2018;44:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhou Y, Liu J, Cui Y, Zhu H, Lu Z. Moisture chamber vs lubrication for corneal protection in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Cornea. 2014;33:1179-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bendavid I, Avisar I, Serov Volach I, Sternfeld A, Dan Brazis I, Umar L, Yassur Y, Singer P, Cohen JD. Prevention of Exposure Keratopathy in Critically Ill Patients: A Single-Center, Randomized, Pilot Trial Comparing Ocular Lubrication With Bandage Contact Lenses and Punctal Plugs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1880-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Poggio EC, Glynn RJ, Schein OD, Seddon JM, Shannon MJ, Scardino VA, Kenyon KR. The incidence of ulcerative keratitis among users of daily-wear and extended-wear soft contact lenses. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:779-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cheng KH, Leung SL, Hoekman HW, Beekhuis WH, Mulder PG, Geerards AJ, Kijlstra A. Incidence of contact-lens-associated microbial keratitis and its related morbidity. Lancet. 1999;354:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pereira CE, Hida RY, Silva CB, de Andrade MR, Fioravanti-Lui GA, Lui-Netto A. Post-photorefractive keratectomy contact lens microbiological findings of individuals who work in a hospital environment. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41:167-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marcet MM, Shtein RM, Bradley EA, Deng SX, Meyer DR, Bilyk JR, Yen MT, Lee WB, Mawn LA. Safety and Efficacy of Lacrimal Drainage System Plugs for Dry Eye Syndrome: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1681-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Germano EM, Mello MJ, Sena DF, Correia JB, Amorim MM. Incidence and risk factors of corneal epithelial defects in mechanically ventilated children. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1097-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hernandez EV, Mannis MJ. Superficial keratopathy in intensive care unit patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:212-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Korb DR, Greiner JV, Glonek T, Esbah R, Finnemore VM, Whalen AC. Effect of periocular humidity on the tear film lipid layer. Cornea. 1996;15:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moon CH, Kim JY, Kim MJ, Tchah H, Lim BG, Chung JK. Effect of Three-Dimensional Printed Personalized Moisture Chamber Spectacles on the Periocular Humidity. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:5039181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |