Published online Feb 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.992

Peer-review started: November 17, 2020

First decision: November 24, 2020

Revised: December 8, 2020

Accepted: December 17, 2020

Article in press: December 17, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2021

Processing time: 69 Days and 6.1 Hours

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a rare congenital heart disease defined by an interruption of the lumen and anatomical continuity between the ascending and descending major arteries. It is usually found within a few hours or days of birth. Without surgery, the chances of survival are low. If IAA patients have an effective collateral circulation established, they can survive into adulthood. However, IAA in adults is extremely rare, with few reported cases.

A 27-year-old woman presented with a 6-year history of progressively worsening shortness of breath and chest tightness on exertion. She had cyanotic lips and clubbing of the fingers. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an enlarged heart and dilation of the main pulmonary artery. There was an abnormal 9 mm passage between the descending aorta and pulmonary artery. The ventricular septal outflow tract had a 14 mm defect. Doppler ultrasound suggested a patent ductus arteriosus and computed tomographic angiography showed the absence of the aortic arch. The diagnoses were ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and definite interruption of the aortic arch. Although surgical correction was recommended, the patient declined due to the surgical risks and was treated with medications to reduce pulmonary artery pressure and treat heart failure. Her condition has been stable for 12 mo of follow-up.

Although rare, IAA should be considered in adults with refractory hypertension or unexplained congestive heart failure.

Core Tip: Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a rare congenital heart defect that is typically diagnosed shortly after birth and likely to be fatal without surgical correction. There are few reports of new IAA diagnoses in adults. In order to compensate for insufficient blood supply to the systemic circulation, IAA patients usually have abundant collateral circulation. This case describes an adult patient who survived due to a ventricular septal defect and a patent ductus arteriosus that allowed some oxygenated blood to be pumped into the descending aorta. IAA should be considered in adults with refractory hypertension or unexplained congestive heart failure.

- Citation: Dong SW, Di DD, Cheng GX. Isolated interrupted aortic arch in an adult: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(4): 992-998

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i4/992.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.992

An interrupted aortic arch (IAA), also known as the absence of an aortic arch, refers to the absence of a connection between the ascending and descending aorta. It is a rare and serious congenital vascular malformation. The main manifestation of IAA is the complete interruption or occlusion of the aortic arch lumen, which is caused by an embryonic developmental disorder. IAA rarely exists alone, and almost all cases are associated with patent ductus arteriosus and a ventricular septal defect, which together are called the triad of interrupted aortic arch. IAA occurs in 3 per million live births and accounts for 1% of all congenital heart diseases[1].

We describe the rare case of a 27-year-old woman presenting with chest distress and shortness of breath, and subsequently diagnosed with IAA.

A 27-year-old woman presented with progressively worsening chest tightness and shortness of breath on exertion.

Six years ago, the patient began to experience chest distress and shortness of breath after activity, which was relieved after rest. The patient had occasional tussiculation but no paroxysmal dyspnea. She had low energy and lack of appetite, but her sleep quality was fair. The patient’s growth and development were within the normal range. Over time, the symptoms of chest tightness worsened, and were accompanied by dizziness and numbness of the extremities.

The patient had a history of incomplete abortion one year ago and had been treated with induced abortion.

The patient had never smoked and had no family history of heart or lung disease. She had congenital heart disease since childhood without standard treatment. The patient stated that she had a "cold" once a month. Symptoms such as shortness of breath and weakness appeared after walking up one flight of stairs and the symptoms were relieved after rest.

On admission, her blood pressure was 100/64 mmHg in both arms and her heart rate was approximately 74 bpm. Physical examination revealed that her heart rate was regular, and there was a 3/6 systolic murmur on the aortic second auscultation area. She had cyanotic lips and clubbing of her fingers.

Routine laboratory examinations were within normal limits.

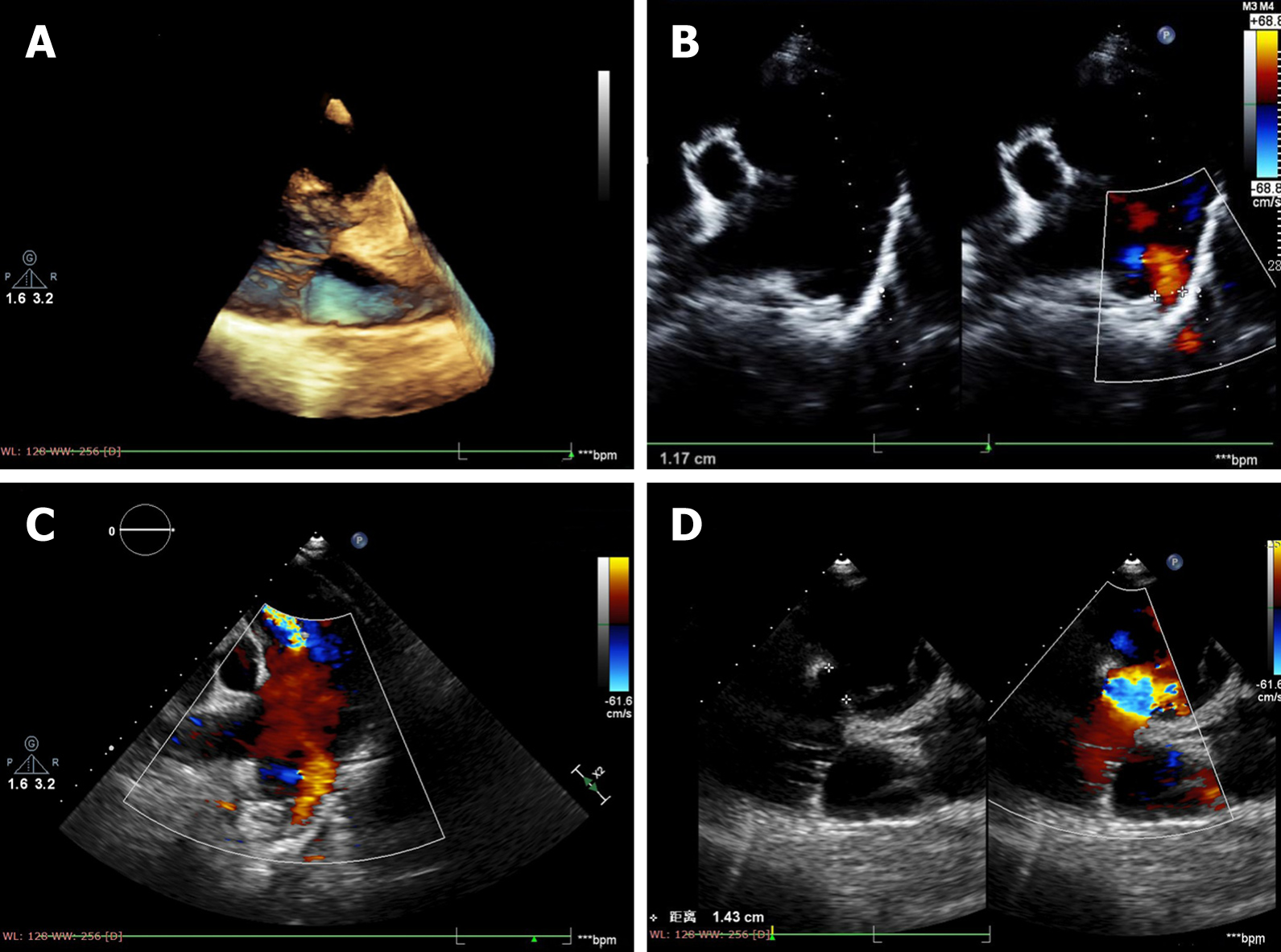

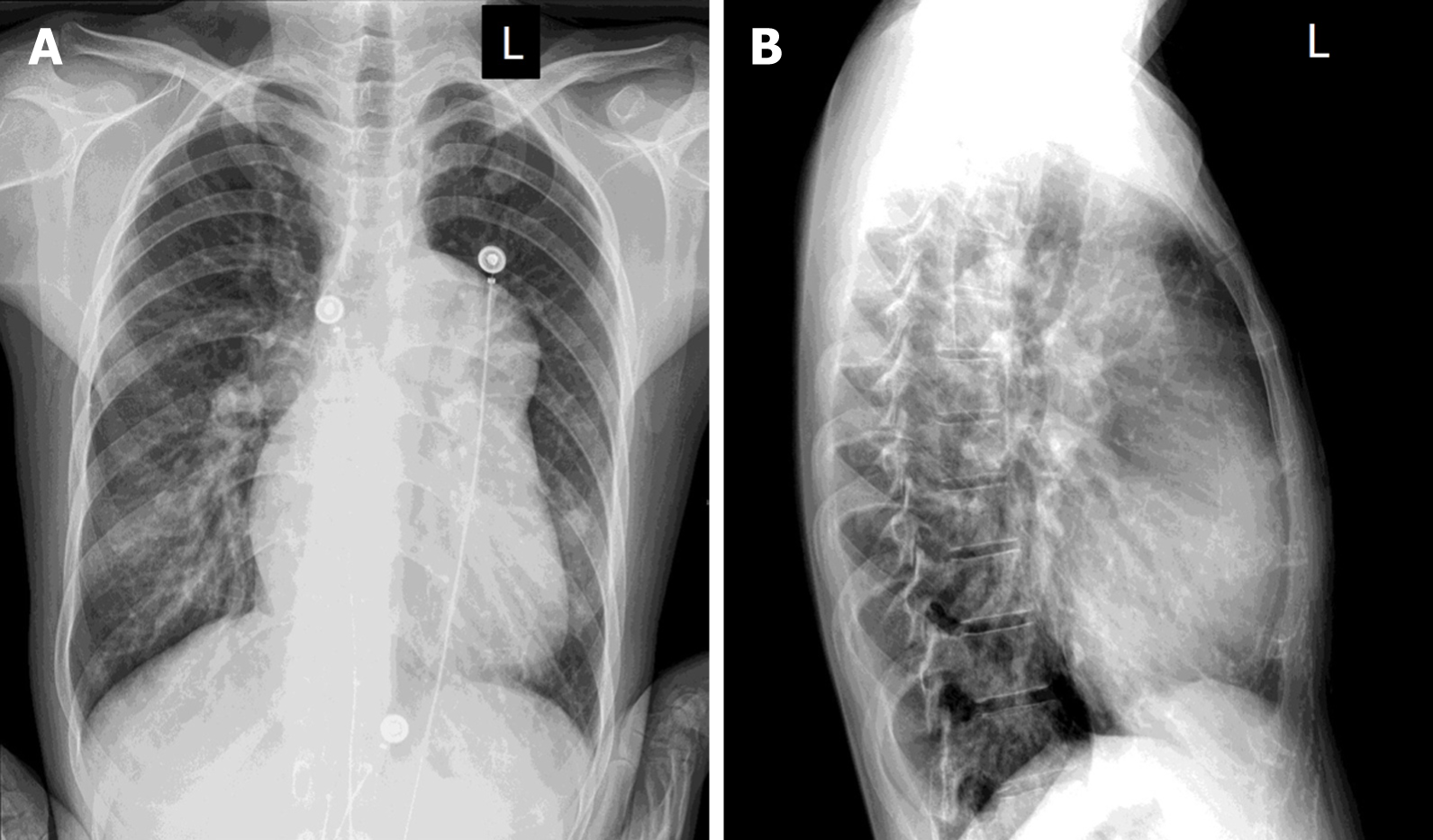

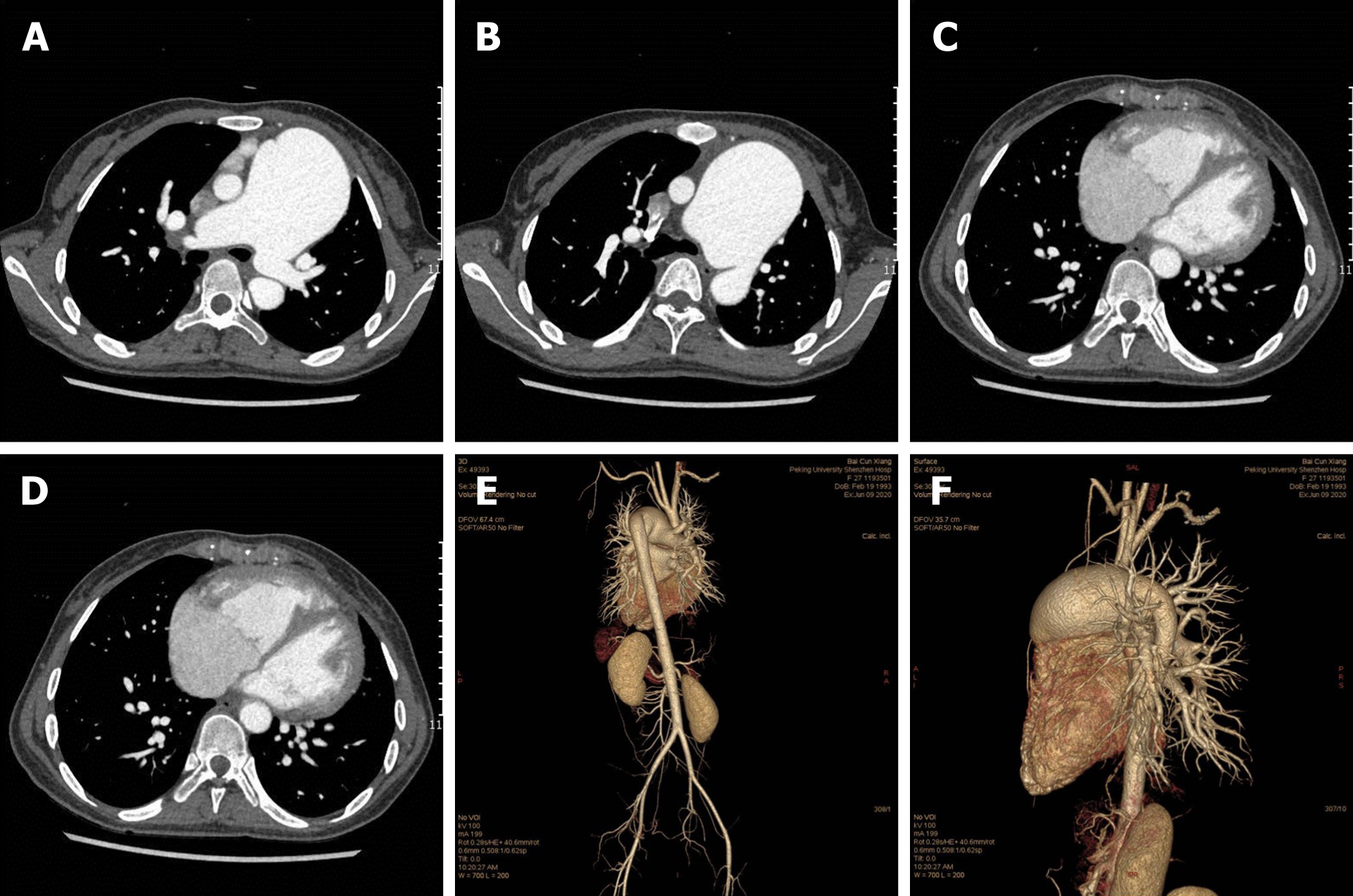

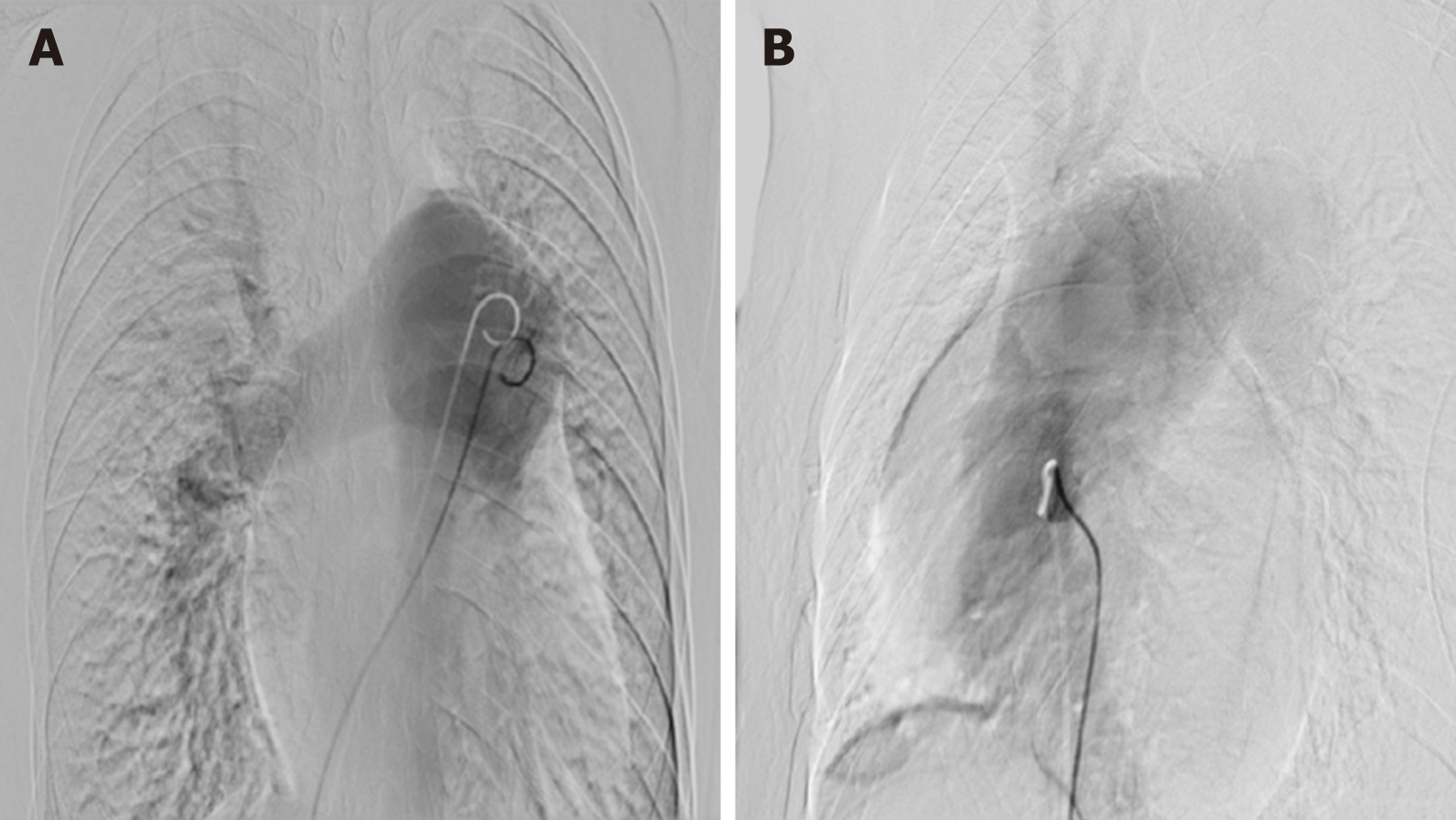

The patient underwent multimodal imaging. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed that the main pulmonary artery was dilated with a diameter of 54 mm. There was an abnormal passage between the descending aorta and pulmonary artery with an inner diameter of 9 mm. The entire heart was enlarged. The continuity of the ventricular septal outflow tract was interrupted, and the defect size was approximately 14 mm. Doppler ultrasound evaluation found bidirectional reflux of abnormal channels between the descending aorta and pulmonary artery, which was thought to be a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in the interrupted region (Figure 1). Chest radiography showed an enlarged heart shadow, a prominent pulmonary artery, and increased lung texture, which was consistent with pulmonary congestion (Figure 2). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed enlargement of the right heart and absence of the aortic arch. The descending aorta originated from the pulmonary trunk, and the junction was 13 mm wide. The diameter of the main pulmonary artery and the right pulmonary artery were thickened. The main pulmonary artery was 54 mm wide, and the right pulmonary artery was 27 mm wide. The ventricular septal wall defect measured 17 mm at the level of the right ventricular outflow tract. The aorta was shifted forward and to the right, straddling the two ventricles (Figure 3). Ven-triculography was performed via the left femoral arteries. Right ventriculography showed pulmonary artery dilatation with residual lung signs. Contrast medium was abnormally seen simultaneously in the left ventricle, ascending aorta, and descending aorta (Figure 4).

Following imaging examination combined with clinical examination, the diagnoses were ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and definite interruption of the aortic arch.

Although surgical correction was recommended, the patient refused due to the surgical risks and underwent conservative therapy with medications to reduce pulmonary artery pressure and treat heart failure.

The patient continues to receive medication to lower pulmonary artery pressure and control ventricular rate. She has no symptoms of cough or sputum. Her mental state, sleep quality, and appetite are normal, and her quality of life has improved in 12 mo of follow-up.

IAA is a very rare congenital malformation defined as the absence of luminal continuity between the ascending and descending portions of the aorta[2]. In general, this cardiac vascular malformation is expected to be fatal in most cases. In infants, its clinical manifestations include severe congestive heart failure. Unless treated, the average survival of 90% of infants is four days[3]. This report describes a very unusual IAA patient who survived to adulthood without diagnosis or treatment due to concomitant cardiac malformations including a ventricular septal defect and a PDA.

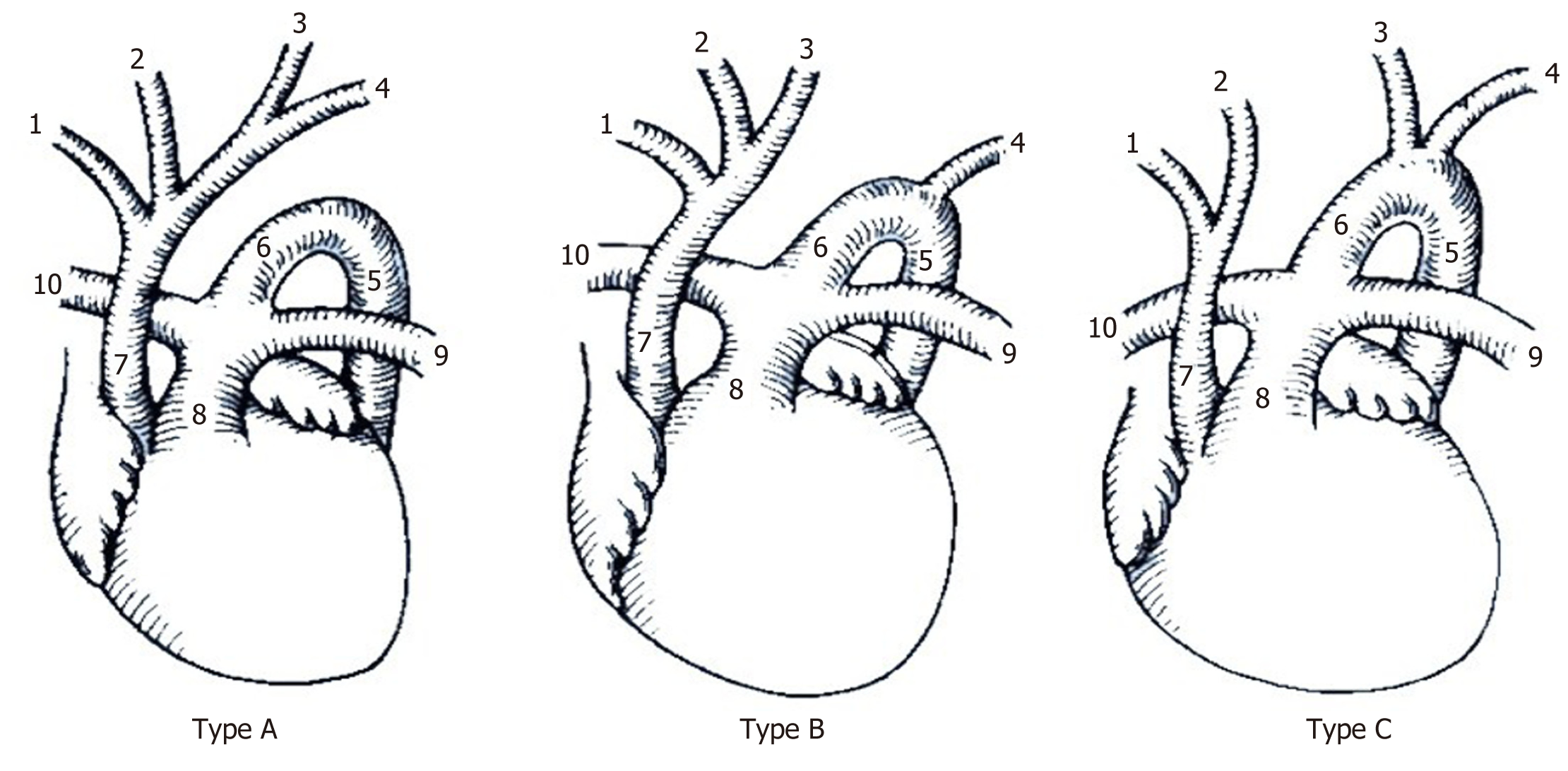

IAA is divided into three different types according to the fault location (Figure 5). The patient in this case was type A, with the aortic arch interrupted at the distal end of the left subclavian artery. Type B is associated with a 22q11.2 deletion, and the aortic arch is dislocated between the origin of the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery. Type C is the rarest type, with the arch of the aorta interrupted at the distal end of the left subclavian artery[4]. In neonates, 53% of cases are type B, followed by type A (43%) and type C (4%)[5]. In adults, a previous review of 38 cases of IAA showed that most cases were type A, and only 6 of these (16%) were type B[6].

Adult presentation of IAA is extremely rare. Patients may be asymptomatic or may present with headache, hypertension, claudication, differences in upper and lower limb blood pressure, limb swelling, congestive heart failure, or aortic dissection[7]. Most patients have associated congenital cardiac anomalies, such as PDA, ventricular septal defect, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, aortopulmonary window, and aberrant innominate arteries. The degree of collateral circulation and PDA are the key factors for survival into adulthood. In this case, the patient’s descending aorta originated from the pulmonary trunk without extensive collateral circulation, leading to inadequate arterial oxygenation. However, the ventricular septal defect and PDA allowed some oxygenated blood to be pumped into the descending aorta, undo-ubtedly contributing to her survival.

Multimodal imaging is vital for the diagnosis and appropriate surgical treatment of IAA. In adults, IAA presents as interruption and separation of the ascending and descending aorta; an abnormal ratio of the inner diameter of the ascending aorta to the main pulmonary artery; widening of the ascending aorta, and narrowing of the descending aorta on CTA. In some patients, thickening of arterial ductus arterioles and tortuosity of the collateral circulation can be observed. The patient in this case had abundant imaging examinations, which play an important role in the diagnosis of IAA.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can show malformations of the heart and aorta and has long been regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of IAA. However, patients often refuse this invasive examination that carries a certain risk and high radiation dose. CTA, echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the leading noninvasive imaging methods for the identification and diagnosis of aortic arch variations. To some extent, they have replaced the invasive ductal angiograph. CTA has a strong spatial resolution, which can clearly show vascular anatomy and collaterals. However, it requires ionizing radiation and cannot be used to evaluate cardiac function. Nevertheless, it is increasingly being accepted as an alternative to MRA for the diagnosis of heart and vascular diseases[1]. Ult-rasonography has a high temporal resolution. It is a simple and feasible screening method. It is irreplaceable for the diagnosis of intracardiac malformations, especially in the evaluation of valvular lesions and hemodynamic changes. MRA has strong soft tissue resolution and has been established to evaluate and diagnose cardiac and vascular abnormalities. It can clearly show the interruption of the myocardium and blood vessel wall. However, the examination time is long, making it a difficult procedure in infants.

IAA has extremely low survival rates, and the main treatment is early surgical intervention, including either bypass or percutaneous stent placement. In neonates and infants, there are many surgical methods, such as end-to-end or end-to-side anastomosis. End-to-end anastomosis can be performed in older children and adults, while interposition transplantation can be performed in older populations.

One report revealed that most adult IAA patients (54%) underwent sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy for correction; 8% underwent percutaneous perforation with stents placed between the ascending and descending aorta, and 10% were managed medically after refusing surgical management[6]. The main complication of this surgical option is paraplegia, with a reported incidence of 0.3%-0.5%[8,9]. The patient in this case was complicated with multiple cardiovascular abnormalities. Considering the surgical risk, conservative drug treatment and long-term follow-up were selected. The goal of treatment is to reduce pulmonary artery pressure, treat heart failure, and reduce cardiovascular risk factors.

In summary, isolated IAA in adults is a rare and serious congenital vascular anomaly. In young patients with hypertension, multimodal imaging examination is important for the diagnosis of this abnormality. CTA, echocardiography, MRI, and aortography combined with physical examination may all contribute to the accurate diagnosis of IAA. Although surgery is the optimal treatment, conservative drug treatment is an option for patients who are poor surgical candidates.

The authors thank the patient and her family as well as the referring radiologists.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zavras N S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Sakellaridis T, Argiriou M, Panagiotakopoulos V, Krassas A, Argiriou O, Charitos C. Latent congenital defect: interrupted aortic arch in an adult--case report and literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2010;44:402-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Canova CR, Carrel T, Dubach P, Turina M, Reinhart WH. [Interrupted aortic arch: fortuitous diagnosis in a 72-year-old female patient with severe aortic insufficiency]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1995;125:26-30. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Collins-Nakai RL, Dick M, Parisi-Buckley L, Fyler DC, Castaneda AR. Interrupted aortic arch in infancy. J Pediatr. 1976;88:959-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chan FP, Hanneman K. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in neonates with congenital cardiovascular disease. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2015;36:146-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patel DM, Maldjian PD, Lovoulos C. Interrupted aortic arch with post-interruption aneurysm and bicuspid aortic valve in an adult: a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;10:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gordon EA, Person T, Kavarana M, Ikonomidis JS. Interrupted aortic arch in the adult. J Card Surg. 2011;26:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Peng L, Qiu Y, Yang Z, Yuan D, Dai C, Li D, Jiang Y, Zheng T. Patient-specific Computational hemodynamic analysis for interrupted aortic arch in an adult: implications for aortic dissection initiation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hudsmith LE, Thorne SA, Clift PF, de Giovanni J. Acquired thoracic aortic interruption: percutaneous repair using graft stents. Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Keen G. Spinal cord damage and operations for coarctation of the aorta: aetiology, practice, and prospects. Thorax. 1987;42:11-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |