Published online Feb 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.898

Peer-review started: October 12, 2020

First decision: November 8, 2020

Revised: November 17, 2020

Accepted: December 16, 2020

Article in press: December 16, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2021

Processing time: 105 Days and 7.4 Hours

Femoral head fracture is extremely rare in children. This may be the youngest patient with femoral head fracture ever reported in the literature. There are few pediatric studies that focus on cases treated with open reduction via the modified Hardinge approach.

A 14-year-old female adolescent suffered a serious traffic accident when she was sitting on the back seat of a motorcycle. A pelvic radiograph and computed tomography revealed a proximal femoral fracture and slight acetabular rim fracture. This was diagnosed as a Pipkin type IV femoral head fracture. An open reduction and Herbert screw fixation was performed via a modified Hardinge approach. After 1-year follow-up, the patient could walk without aid and participate in physical activities. The X-ray results showed that the fractures healed well with no evidence of complications.

Open reduction and Herbert screw fixation is an available therapy to treat Pipkin type IV femoral head fractures in children.

Core Tip: Femoral head fractures are extremely rare in children. We have reported an adolescent with a Pipkin type IV fracture treated with open reduction and screw fixation. Excellent clinical function and radiographic fracture healing were observed after 1 year.

- Citation: Liu Y, Dai J, Wang XD, Guo ZX, Zhu LQ, Zhen YF. Open reduction and Herbert screw fixation of Pipkin type IV femoral head fracture in an adolescent: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(4): 898-903

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i4/898.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.898

Femoral head fractures are uncommon injuries in adults and more rarely seen in children and adolescents. With high energy injuries increasing, especially in car accidents, hip traumas are becoming more frequent. The literature shows that about 5%-15% of hip dislocations are accompanied by proximal femoral fractures[1]. The most commonly used classification, described by Pipkin, is to use the fracture line location and lesion in the femoral neck or acetabulum to define the type of fracture[2]. Patients with a Pipkin type I or II injury have more optimal outcomes than those with a Pipkin type III or IV injury[3]. To our knowledge, few articles have reported femoral head fractures in skeletally immature patients. We operated on a 14-year-old female diagnosed with a Pipkin type IV fracture. After one year, excellent clinical function and radiographic fracture healing were observed.

A 14-year-old Chinese female was transferred to our hospital with the chief complaints of severe hip pain and difficult thigh movement after being struck by a car when she was riding pillion on a motor bike 4 d before.

Due to left hip pain and limited movement, radiographic examinations were performed in the emergency room of the local hospital. The patient was diagnosed with “hip dislocation and femoral head fracture.” After 4 d of inpatient observation and skeletal traction the patient was transported to our department.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The patient exhibited hip tenderness and limitation of motion. No neurovascular injury was observed.

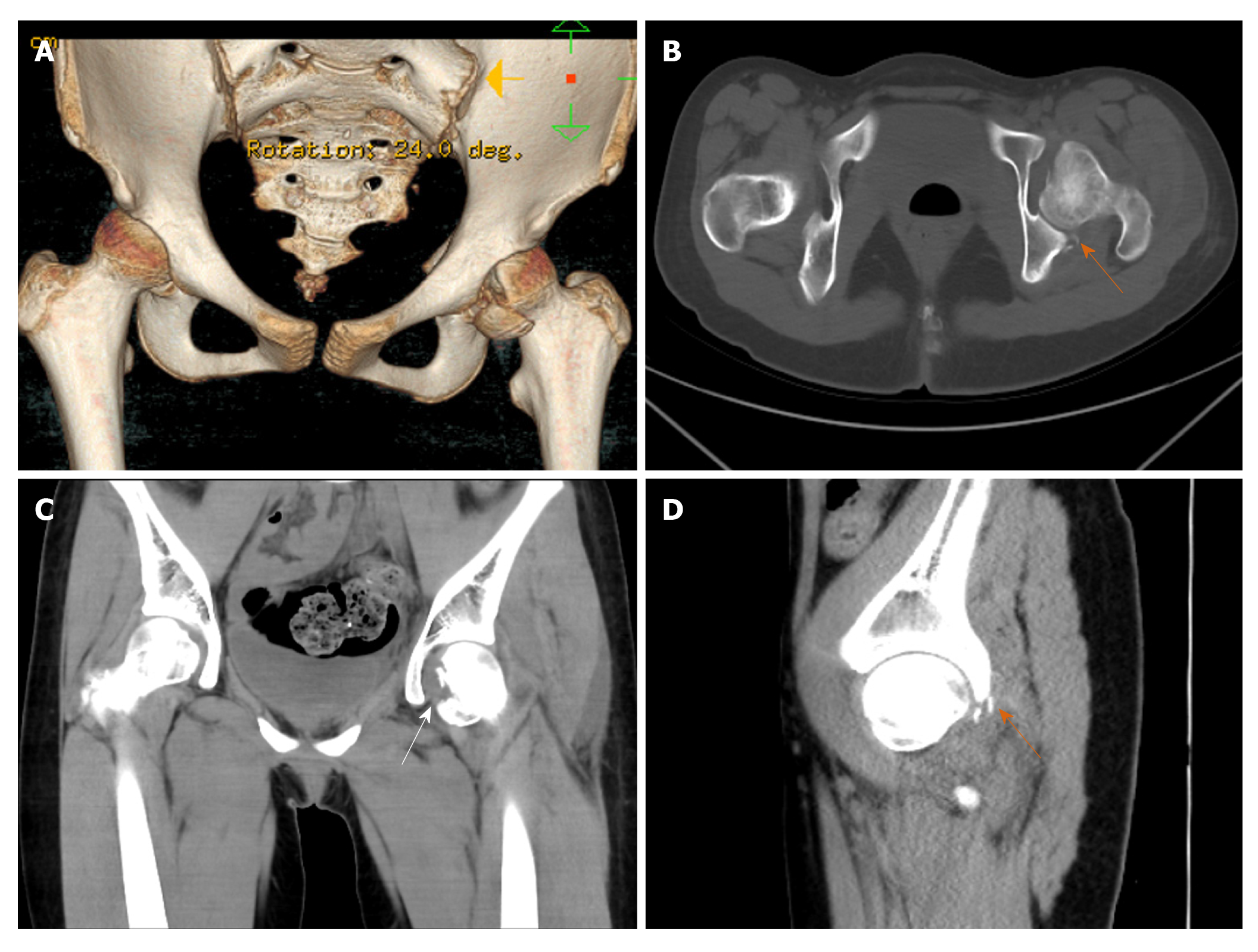

A three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a femoral head fracture. Axial and sagittal CT scans showed the posterior acetabulum with slight displacement. A coronal CT scan showed the fracture line extending superior to the fovea centralis (Figure 1).

The final diagnosis was a femoral head fracture associated with posterior acetabular fracture categorized as a Pipkin type IV fracture.

The patient underwent skeletal traction for 7 d including 4 d in the local department and 3 d in our hospital.

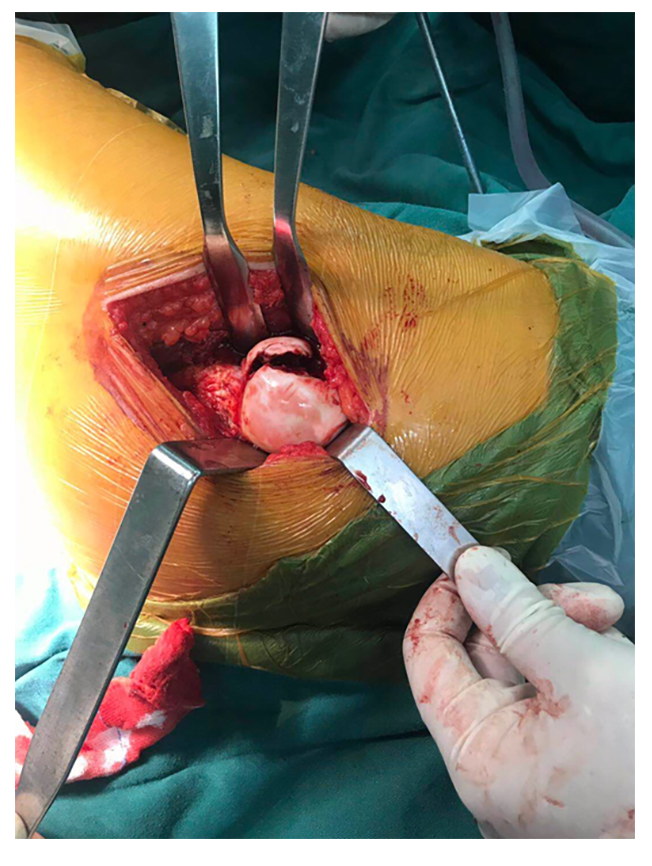

After a general physical check-up and confirmation that vital signs were stable, we opted for surgical intervention on the 7th d after injury. We chose a modified Hardinge approach to expose the operative field with the patient in a side-lying position after general anesthesia. A longitudinal skin incision was made in the middle of the greater trochanter. The inferior fat and fascia were incised and retracted. After blunt dissection and retraction of the anterior third of the gluteus medius, electrosurgical dissection was used to split the tendinous portion of the distal gluteus medius and the anterior part of the vastus lateralis muscles. The capsule was exposed, and a “T”-shaped incision was made. The femoral head was dislocated anteriorly with flexion, extension and adduction. A piece of the large fragment and some smaller articular debris were detected in the nonweight-bearing area (Figure 2). The large fragment comprised 20% of the articular surface and was notably rotated. The ligamentum teres was ruptured from its insertion into the acetabulum. After resection of the torn ligament and articular purge, the major fragment was manipulated carefully back into place and an anatomical reduction of the articular surface was obtained. Three Herbert screws were used to fix the fragment with specific attention to avoiding screw protrusion. Then the hip joint was reduced by gentle abduction and internal rotation. We tested the range of motion and joint stability. The reduced hip demonstrated no limitation of passive activity. The wound was closed, and a drain was inserted. Intraoperative x-rays demonstrated an ideal reduction of the femoral head.

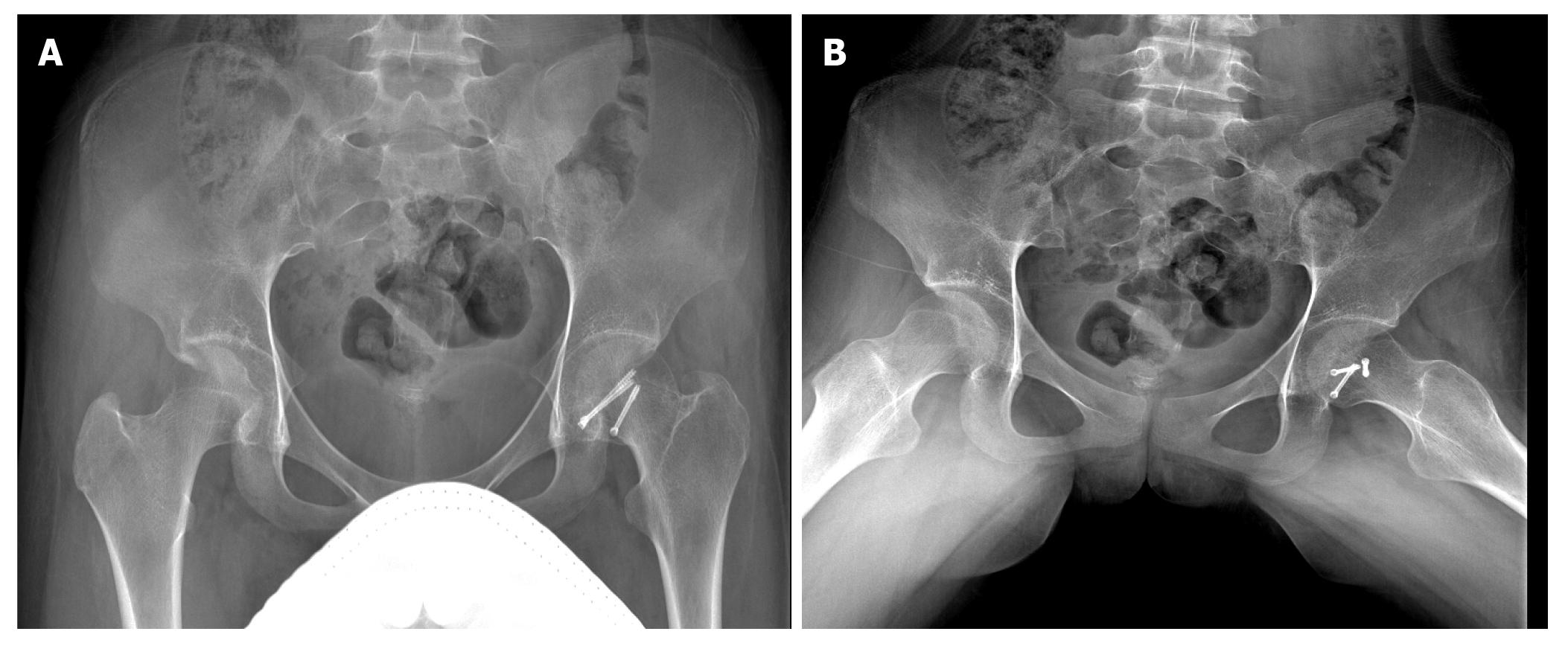

The patient was compliant with physical exercises and partial weight-bearing with crutches after surgery. The postoperative hospitalization time was 2 wk. Follow-up occurred 4, 8 and 12 wk postoperatively. At 6 mo after discharged from hospital she returned to school and could walk without crutches. One year after the surgery the patient had no left hip pain and was playing partial-contact sports without difficulty. Her left hip range of motion demonstrated hip flexion range of 0° to 100°, internal rotation to 20°, external rotation to 40°, abduction to 30° and adduction to 30°. Radiographs 12 mo after the injury demonstrated fracture healing with no evidence of osteonecrosis (Figure 3A and 3B).

Pipkin fractures are rare injuries, especially in the pediatric population. There are few papers in the literature that describe femoral head fractures in skeletally immature patients. The previous literature has reported an incidence of two in a million per year[4]. With the growing incidence of traffic accidents, the occurrence of hip fracture-dislocation has increased[5]. The mechanism of this injury is very complicated due to the indirect force intensity to the hip caused by impact transmitted along the femoral shaft[6]. Compared with adults, associated fractures are more uncommon in children with traumatic hip dislocation[7]. Cartilaginous pliability and ligamentous laxity in children provide increased elasticity, which could explain the rarity of this type of fracture in children.

The Pipkin system is the typical classification for femoral head fracture dislocations[2,8]. Type IV lesions, which are characterized by lesions of both the femoral head and acetabular rim, usually have a poor prognosis[9]. Treatment options for Pipkin type IV fractures include fragment excision, internal fixation and arthroplasty[10-12]. The primary goals of open reduction are to remove loose fragments, to restore stability to the hip joint and to ensure concentric hip reduction.

The optimal timing of surgery is still controversial. Some literature indicated worse outcomes for Pipkin fractures with delayed surgery compared with those who had immediate surgery[13]. However, other studies showed no statistically significant differences in outcome when comparing time of surgery with hip reduction, definitive operative intervention or the anatomic operative approach to injury[3].

Skeletal traction is a temporary measure in acetabular and proximal femoral fractures when surgical intervention is delayed[14]. In our case, bony traction was performed immediately in the local hospital so that a prompt concentrated hip reduction and temporary immobilization were achieved. This may be one reason for the absence of complications.

In theory, treatment through surgical hip dislocation or a posterior approach to fix both the acetabulum and femoral head is advocated in dealing with Pipkin type IV fractures[15,16]. However, we chose a modified Hardinge approach for the following reasons. First, the patient was skeletally immature with an obvious greater trochanteric epiphyseal line on the CT scan. A digastric trochanteric flip osteotomy might cause growth disorders of the proximal femur. Second, the larger fragment was located on the inferior and anterior portion of the femoral head, which would be difficult to fix through a posterior approach. Third, there were slight fractures with no displacement in the posterior acetabular rim that had no need for reconstruction. Additionally, the modified Hardinge approach was the most familiar approach for us and is widely used in the treatment of pediatric hip septic arthritis and femoral neck fracture[17]. This modified approach compromised little of the abductor function; most of the gluteus medius retained function[18]. Also, the literature showed there was no significant statistical difference in the therapeutic effect among anterior, posterior or trochanteric-flip approaches for repair of femoral head fractures[5].

There is still disagreement over whether fragments should be fixed or removed[19]. Most surgeons agree that large fracture fragments and those located in the load-bearing area should be retained and anatomically repositioned[20]. The diameter of the large fragment in this case was about two centimeters; we chose to operate using Herbert screw fixation. Other small debris and the severed ligamentum teres were removed to facilitate the reduction of hip joint. Radiographs of the pelvis were obtained after manipulation to check concentric reduction. The most common complications are nonunion, femoral head avascular necrosis, heterotopic ossification, osteoarthritis and stiffness[5]. None of these sequelae were seen after early exercise and partial weight-bearing. It is particularly important to point out that the follow-up time is relatively short. Long term clinical follow-up is needed to fully evaluate the prognosis.

This case report describes a rare case of Pipkin type IV fracture in a 14-year-old female. With open reduction and Herbert screw fixation via a modified Hardinge approach, satisfactory patient outcomes were observed without major complications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ciccone MM, Karayiannakis AJ S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Sahin V, Karakaş ES, Aksu S, Atlihan D, Turk CY, Halici M. Traumatic dislocation and fracture-dislocation of the hip: a long-term follow-up study. J Trauma. 2003;54:520-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pipkin G. Treatment of grade IV fracture-dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39-A:1027-42 passim. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Marchetti ME, Steinberg GG, Coumas JM. Intermediate-term experience of Pipkin fracture-dislocations of the hip. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:455-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Kelly PJ, Lipscomb PR. Primary vitallium-mold arthroplasty for posterior dislocation of the hip with fracture of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40-A:675-680. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gillespie P, Aprato A, Bircher M. Hip Dislocation and Femoral Head Fractures. In: Bentley G. (eds) European Surgical Orthopaedics and Traumatology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014: 2179-2202. |

| 6. | Henle P, Kloen P, Siebenrock KA. Femoral head injuries: Which treatment strategy can be recommended? Injury. 2007;38:478-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chun KA, Morcuende J, El-Khoury GY. Entrapment of the acetabular labrum following reduction of traumatic hip dislocation in a child. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thompson VP, Epstein HC. Traumatic dislocation of the hip; a survey of two hundred and four cases covering a period of twenty-one years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33-A:746-78; passim. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Giannoudis PV, Kontakis G, Christoforakis Z, Akula M, Tosounidis T, Koutras C. Management, complications and clinical results of femoral head fractures. Injury. 2009;40:1245-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kurtz WJ, Vrabec GA. Fixation of femoral head fractures using the modified heuter direct anterior approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:675-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oransky M, Martinelli N, Sanzarello I, Papapietro N. Fractures of the femoral head: a long-term follow-up study. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Solberg BD, Moon CN, Franco DP. Use of a trochanteric flip osteotomy improves outcomes in Pipkin IV fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:929-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lin D, Lian K, Chen Z, Wang L, Hao J, Zhang H. Emergent surgical reduction and fixation for Pipkin type I femoral fractures. Orthopedics. 2013;36:778-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Matullo KS, Gangavalli A, Nwachuku C. Review of Lower Extremity Traction in Current Orthopaedic Trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:600-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1119-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Droll KP, Broekhuyse H, O'Brien P. Fracture of the femoral head. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:716-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patterson JT, Tangtiphaiboontana J, Pandya NK. Management of Pediatric Femoral Neck Fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26:411-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pai VS. A modified direct lateral approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2002;10:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ross JR, Gardner MJ. Femoral head fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park MS, Her IS, Cho HM, Chung YY. Internal fixation of femoral head fractures (Pipkin I) using hip arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:898-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |