Published online Feb 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.847

Peer-review started: October 19, 2020

First decision: December 3, 2020

Revised: December 17, 2020

Accepted: December 26, 2020

Article in press: December 26, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2021

Processing time: 97 Days and 23.2 Hours

Rectal prolapse in young women is rare. Although laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy is the standard procedure because of its lower recurrence rate, postoperative infertility is a concern. Perineal rectosigmoidectomy (Altemeier procedure) is useful for these patients. However, the risk of anastomotic leakage should be considered. Recently, the usefulness of fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green (ICG) to prevent anastomotic leakage was reported. We report a case of an adolescent woman with complete rectal prolapse who underwent ICG fluorescence imaging-assisted Altemeier rectosigmoidectomy.

A 17-year-old woman who had a mental disorder was admitted to our hospital for treatment for water intoxication. The patient also suffered from rectal prolapse, approximately 3 mo before admission. She was referred to our surgical department because recurrent rectal prolapse could worsen her psychiatric disorder. Approximately 10 cm of complete rectal prolapse was observed. However, the mean maximum anal resting and constriction pressures were within normal limits on anorectal manometry. Because she had the desire to bear children in the future, she underwent Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy to prevent surgery-related infertility. We performed ICG fluorescence imaging at the same time as surgery to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage. Her postoperative course was uneventful, and the rectal prolapse was completely resolved. She continued to do well 18 mo after surgery, without recurrence of the rectal prolapse.

ICG fluorescence imaging-assisted Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy is useful in preventing postoperative anastomotic leakage in young as well as elderly patients.

Core Tip: Rectal prolapse mainly occurs in elderly women and is rare in young women. Perineal approaches, including perineal rectosigmoidectomy (Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy), are useful for not only elderly patients but also young women who desire pregnancy. However, postoperative anastomotic leakage should be considered. Recently, fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green (ICG) has provided a real-time assessment of intestinal perfusion to prevent the occurrence of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery. We describe here a case of a female adolescent patient with complete rectal prolapse who underwent ICG fluorescence imaging-assisted Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy to prevent postoperative anastomotic leakage as well as surgery-related infertility.

- Citation: Yamamoto T, Hyakudomi R, Takai K, Taniura T, Uchida Y, Ishitobi K, Hirahara N, Tajima Y. Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy with indocyanine green fluorescence imaging for a female adolescent with complete rectal prolapse: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(4): 847-853

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i4/847.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.847

Rectal prolapse is defined as a rare condition, in which the rectum loses its normal attachments that keep it inside the body. As such, the rectum turns inside out and sticks out through the anus. Rectal prolapse is rarely life threatening; however, it severely affects patient quality of life[1]. Although rectal prolapse can occur in any person, it is most commonly seen in elderly and female patients[2]. The exact cause of rectal prolapse remains unclear but some potential causative factors have been proposed, including an abnormally deep pouch of Douglas, pudendal nerve neuropathy, anal sphincter weakness, and increased intraabdominal pressure[3]. Some authors have speculated about the relationship between rectal prolapse and eating disorders in young women[4].

Various operative procedures are available for treating rectal prolapse and are generally categorized into abdominal and perineal approaches. Abdominal approaches include rectopexy, with or without resection of the sigmoid colon. Recently, laparoscopic or robotic rectopexy using ventral mesh has been reported[5]. On the other hand, perineal approaches include perineal rectosigmoidectomy (known as the Altemeier procedure[6]), rectal mucosal resection (Delorme repair)[7], and anal encirclement (Thiersch procedure)[7].

Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy is currently the gold standard procedure among the abdominal approaches because of its low rate of recurrence. However, the issue of postoperative infertility raises concerns in using mesh rectopexy for young women. On the other hand, perineal approaches are likely to be used for elderly or high-risk patients because of their lower morbidity and minimally invasive nature. Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy has been reported as the most effective procedure in terms of its low recurrence rate and low degree of invasiveness[8]. However, this procedure involves rectosigmoid resection, and postoperative anastomotic leakage can lead to a dismal outcome. Recently, fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green (ICG) has provided for a real-time assessment of intestinal perfusion and can help prevent the occurrence of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery[9].

We describe herein a case of an adolescent female patient with complete rectal prolapse who underwent ICG fluorescence imaging-assisted Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy to prevent postoperative anastomotic leakage as well as surgery-related infertility.

A 17-year-old female who was hospitalized in the Department of Psychiatry to treat a mental disorder suffered from rectal prolapse. She was referred to our surgical department because recurring rectal prolapse could worsen her psychiatric disorder.

The patient’s symptoms started approximately 3 mo before admission. She had repeated rectal prolapse due to chronic, frequent, and severe diarrhea from spice abuse, including taking 15 g of chili pepper at each meal, and a laxative addiction.

The patient was diagnosed with a mental disorder 1 year before admission. She was hospitalized in the Department of Psychiatry for the treatment of water intoxication 1 mo before being referred to our department.

Other history could cause rectal prolapse were excluded. Her family history has nothing notable.

The patient had anorexia, with a strong drive for thinness. Her height was 156.8 cm, her body weight was 40.0 kg, and her body mass index was 16.3 kg/m2. On physical examination, rectal prolapse measuring 10 cm from the anal verge was visible and easily reproducible. The anal sphincter tonus was normal and there was no evidence of a tumor on digital rectal examination or anoscopy, except for Goligher's grade I internal hemorrhoids. The mean maximum resting pressure and the voluntary anal constriction pressure were within normal limits on anorectal manometry.

No abnormalities were found in the patient's laboratory examinations.

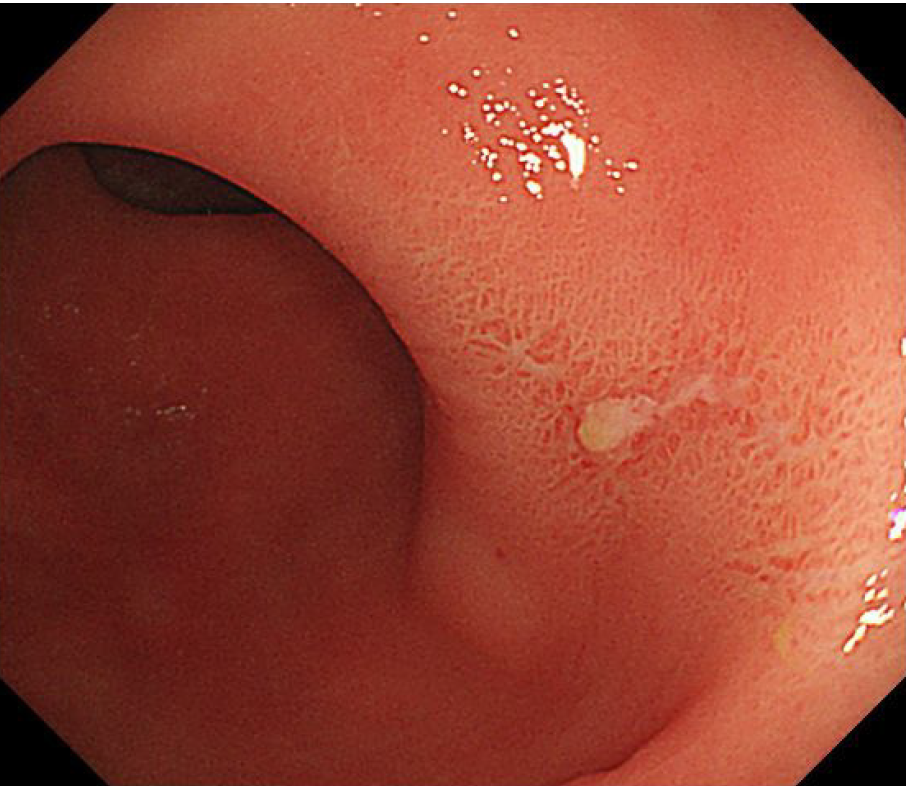

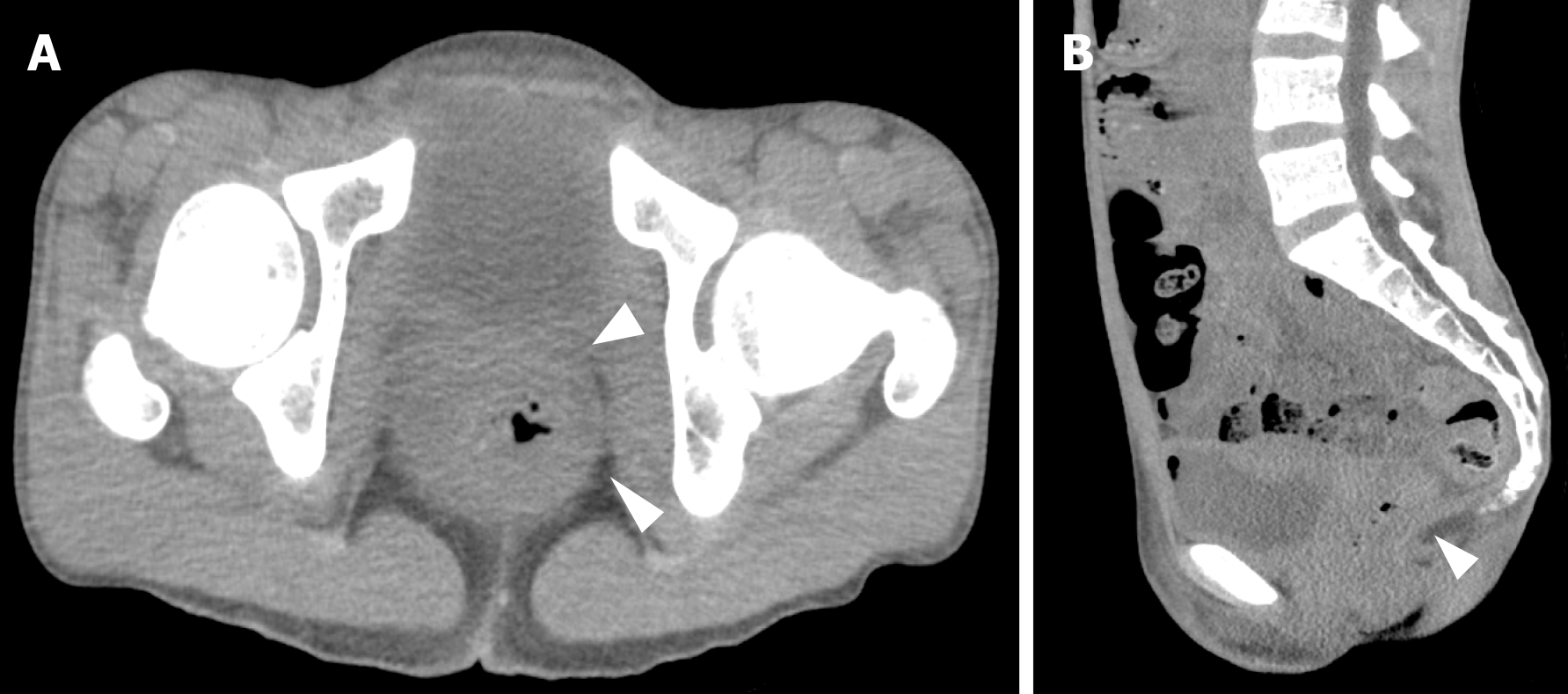

Total colonoscopy revealed redness and erosion in the rectal mucosa related to rectal prolapse (Figure 1). There was no evidence of other colonic pathologies. Abdominal computed tomography scans demonstrated that the peritoneal reflection lay below the lower sacrum, accompanied by a thickened rectal wall (Figure 2).

Complete rectal prolapse.

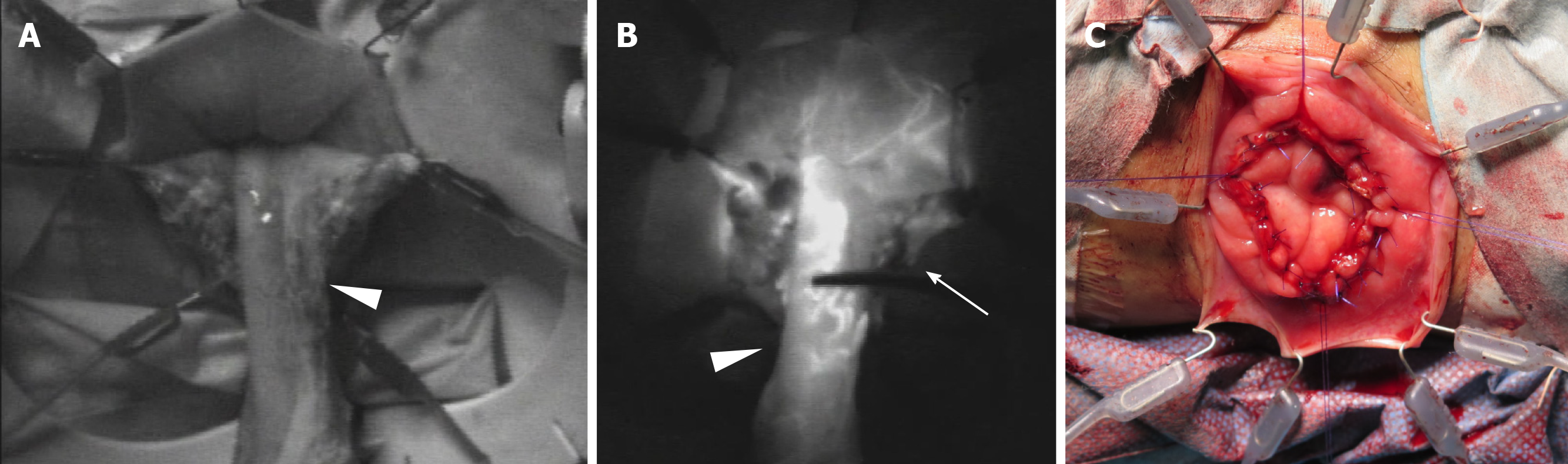

The patient was scheduled to undergo an elective Altemeier perineal rectosigmoid-ectomy. She was placed in the lithotomy position under epidural anesthesia combined with sedation. A large reddish section of the rectum, 10 cm in length, protruded from the anal opening (Figure 3). First, the rectum was pulled out, and then a circumferential full-thickness incision was made in the rectum at 2.0 cm above the dentate line. After sliding out the remnant rectum as much as possible, the perfusion of the proximal rectum was evaluated using near-infrared radiation (NIR) fluorescence imaging after an intravenous administration of ICG at a concentration of 0.2 mg/kg (Figure 4). After confirming rectal blood flow under NIR fluorescence imaging, the rectum was transected at the dentate line, with good perfusion. After performing levatorplasty, an end-to-end anastomosis was created using 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures. The operation time was 202 min, and the estimated blood loss was less than 10 g.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and she was transferred to the psychiatric ward 2 d after surgery. The rectal prolapse was completely resolved, and the patient continued to do well without recurrence of the rectal prolapse at 18 mo after surgery.

Rectal prolapse is a rare condition, and the prevalence has been estimated to be approximately 2.5 per 100000 people[10]. The most common age for rectal prolapse is younger in males than in females because there are some differences in the cause of rectal prolapse between males and females. Morphological or functional abnormalities are the main cause in males, while acquired weakness of the pelvic floor muscles due to several mechanical factors, such as pregnancy, labor and childbirth, is the major cause in females[11].

Young patients with pelvic organ prolapse, including rectal prolapse, tend to have a family history of the disease, suggesting that genetic factors may be involved in the occurrence of rectal prolapse[12]. Our patient had no family history of any type of pelvic organ prolapse, and she was only 17-years-old. The resting and constriction pressures of her anal sphincter muscle were normal on digital examination and anorectal manometry. Moreover, she was thin and had persistent severe diarrhea due to mental health problems with anorexia, spice abuse, and laxative addiction, which could lead to weakness of the anal sphincter or pelvic floor muscles associated with sarcopenia. In addition, she had great anxiety about recurring rectal prolapse, and radical surgery was thus expected to improve her mental status.

Many surgical procedures have been proposed for the treatment of rectal prolapse. After transabdominal surgery, including laparoscopic rectopexy, the recurrence rate is reported to be relatively low, approximately 10%[13], and a high incidence of constipation after rectopexy has been reported; the new occurrence rate is approximately 15%, and the deterioration rate in patients who had constipation is approximately 50%[14]. On the other hand, transperineal approaches characterized as minimally invasive surgery have a higher recurrence rate than transabdominal rectopexy, which were reported as zero to 30%[15].

From the perspective of recurrence risk after surgery, transabdominal rectopexy would be beneficial for patients with rectal prolapse. However, the primary concern in our patient was an increased risk of infertility after mesh rectopexy because the patient was a young (17-year-old) woman. Hogan et al[16] recently reported a safe delivery after laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse with the use of synthetic mesh for women aged 20-year-old to 40-year-old. They described no adverse impact on the outcome of pregnancy and delivery and that pregnancy was not associated with recurrence of the prolapse or pelvic floor symptoms. However, there are no reports related to fertility in adolescent girls following intraabdominal mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Therefore, we selected transperineal surgery, i.e., Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy, in our case of a 10-cm-long rectal prolapse.

Our patient had normal anal sphincter function, which indicated impaired function of the levator ani muscle. Therefore, we performed levatorplasty for the patient. Although increased daily frequency of stools or fecal incontinence has been reported as postoperative complications of the Altemeier procedure[17], these symptoms were not observed in our patient, partly because she managed her mental illness and recovered from spice abuse and laxative addiction after surgery.

Anastomotic leakage is the most serious problem after the Altemeier procedure, with an incidence of 5.9%[17], and it can lead to life-threatening subsequent complications because patients with rectal prolapse are often elderly. The likely risk factors for anastomotic leakage are as follows: (1) Impaired blood supply; (2) High-tension anastomosis; and (3) Increased intraluminal pressure[18]. Recently, visualization of the blood flow at the anastomotic site using ICG fluorescence imaging has been reported to reduce the occurrence of anastomotic leakage in colorectal cancer surgery, especially for rectal cancer[9]. In our patient, ICG fluorescence imaging guidance was useful for identifying an adequate transection line for the rectum by visualizing the rectal blood flow. ICG fluorescence imaging is beneficial for estimating blood flow in real time, but it is subjective and is not capable of evaluating subtle changes in blood flow. Further studies on ICG fluorescence imaging are thus needed to achieve real-time high-resolution visualization and determine an optimal cutoff value for quantitative assessments of blood flow to reduce anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery.

We performed the Altemeier procedure as a meshless perineal approach for a female adolescent with complete rectal prolapse, to avoid infertility after surgery. The information from ICG fluorescence imaging was helpful in making decisions concerning an adequate transection line for the rectum, which may help reduce anastomotic leakage.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen S, Jin C S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Altomare DF, Binda G, Ganio E, De Nardi P, Giamundo P, Pescatori M; Rectal Prolapse Study Group. Long-term outcome of Altemeier's procedure for rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:698-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Tou S, Brown SR, Nelson RL. Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD001758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Madiba TE, Baig MK, Wexner SD. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005;140:63-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Guerdjikova AI, O'Melia A, Riffe K, Palumbo T, McElroy SL. Bulimia nervosa presenting as rectal purging and rectal prolapse: case report and literature review. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:456-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Faucheron JL, Trilling B, Barbois S, Sage PY, Waroquet PA, Reche F. Day case robotic ventral rectopexy compared with day case laparoscopic ventral rectopexy: a prospective study. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:695-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Prasad ML, Pearl RK, Abcarian H, Orsay CP, Nelson RL. Perineal proctectomy, posterior rectopexy, and postanal levator repair for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:547-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Christiansen J, Kirkegaard P. Delorme's operation for complete rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 1981;68:537-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Emile SH, Elfeki H, Shalaby M, Sakr A, Sileri P, Wexner SD. Perineal resectional procedures for the treatment of complete rectal prolapse: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2017;46:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Blanco-Colino R, Espin-Basany E. Intraoperative use of ICG fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22:15-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | RIPSTEIN CB, LANTER B. Etiology and surgical therapy of massive prolapse of the rectum. Ann Surg. 1963;157:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alcalay M, Stav K, Eisenberg VH. Family history associated with pelvic organ prolapse in young women. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1773-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McLean R, Kipling M, Musgrave E, Mercer-Jones M. Short- and long-term clinical and patient-reported outcomes following laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy using biological mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective cohort study of 224 consecutive patients. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:424-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Varma M, Rafferty J, Buie WD; Standards Practice Task Force of American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the management of rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mimura T, Fukudome I, Kobayashi M, Kuramoto S. Surgery for Complete Rectal Prolapse in Adults-A Historical Perspective and How to Select an Appropriate Procedure. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2012;65:827-832. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hogan AM, Tejedor P, Lindsey I, Jones O, Hompes R, Gorissen KJ, Cunningham C. Pregnancy after laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy: implications and outcomes. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:O345-O349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trompetto M, Tutino R, Realis Luc A, Novelli E, Gallo G, Clerico G. Altemeier's procedure for complete rectal prolapse; outcome and function in 43 consecutive female patients. BMC Surg. 2019;19:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guyton KL, Hyman NH, Alverdy JC. Prevention of Perioperative Anastomotic Healing Complications: Anastomotic Stricture and Anastomotic Leak. Adv Surg. 2016;50:129-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |