Published online Feb 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.830

Peer-review started: April 17, 2020

First decision: April 24, 2020

Revised: May 1, 2020

Accepted: December 10, 2020

Article in press: December 10, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2021

Processing time: 282 Days and 23.7 Hours

Haematogenous osteomyelitis is an extremely rare disease occurring in adults, especially in developed countries. It is clearly a systemic infection, because bacteraemia spreads over proximal and distal long bones or paravertebral plexuses, resulting in acute or chronic bone infection and destruction.

A 46-year-old Caucasian male was complaining of a left thigh pain. It is known from the anamnesis that the patient developed severe pneumonia three months ago before the onset of these symptoms. The patient was diagnosed with haematogenous osteomyelitis, which developed a turbulent course and required complex combination therapy. The primary pathogen is thought to be Anaerococcus prevotii, which caused pneumonia before the onset of signs of osteomyelitis. Unfortunately, due to the complexity of identifying anaerobes and contributing nosocomial infections, the primary pathogen was not extracted immediately. After the manifestation of this disease, pathological fractures occurred in both femurs, as well as purulent processes in the lungs and molars accompanied. The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and countless amounts of orthopaedic and reconstructive surgeries, but no positive effect was observed. The patient underwent osteosynthesis using an Ilizarov’s external fixation apparatus, re-fixations, external AO, debridements, intrame-dullary osteosynthesis with a silver-coated intramedullary nail, abscessotomies. The right femur healed completely after the pathological fracture and osteomyelitis did not recur. Left femur could not be saved due to non-healing, knee contracture and bone destruction. After almost three years of struggle, it was decided to amputate the left limb, after which the signs of osteomyelitis no longer appeared.

To sum it all up, complicated or chronic osteomyelitis requires surgery to remove the infected tissue and bone. Osteomyelitis surgery prevents the infection from spreading further or getting even worse up to such condition that amputation is the only option left.

Core Tip: Haematogenous osteomyelitis is an extremely rare disease in adults. Even rarer are pathological fractures that occur as a result. We present a clinical case in which a 46-year-old patient developed haematogenous osteomyelitis after pneumonia. Both femurs were damaged, but the right one was preserved thanks to the preventive built-in AO external fixation. The left thigh was amputated and the signs of osteomyelitis did not recur. The pathogen that caused this insidious disease, Anaerococcus prevotii, has not been reported in the literature as a cause of osteomyelitis. Moreover, there are no reported cases of osteomyelitis affecting both femurs at once.

- Citation: Daunaraite K, Uvarovas V, Ulevicius D, Sveikata T, Petryla G, Kurtinaitis J, Satkauskas I. Reciprocal hematogenous osteomyelitis of the femurs caused by Anaerococcus prevotii: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(4): 830-837

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i4/830.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i4.830

Haematogenous osteomyelitis is an extremely rare disease occurring in adults, especially in industrial countries. It is a heterogeneous infection regarding the etiology and treatment, and is one of the most difficult infections to cure, as no single management protocol exists[1]. It is classified into acute, sub-acute or chronic, according to the time of evolution. Acute osteomyelitis has usually a good response to antibacterial therapy and, if necessary, to surgical treatment. On the opposite, chronic osteomyelitis represents a great therapeutic challenge, requires more effort and medical intervention, becoming surgery essential to obtain the best results[2,3].

A single pathogenic organism is almost always extracted from the bone in haematogenous osteomyelitis. In adults, Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism isolated. However, other gram-positive cocci (including coagulase-negative staphylococci and Streptococcus spp.), gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic organisms (listed in descending order of incidence) are also frequently isolated, and multiple organisms are usually isolated in contiguous focus osteomyelitis. Although, there is not a single reported case of haematogenous osteomyelitis caused by Anaerococcus prevotii[4].

Incompletely cured acute osteomyelitis progresses to chronic, which is much more difficult to treat. Symptoms that occur with this condition include: Pain in the affected area in the bones, swelling, redness, and tenderness. The rupture of pus from an opening into an infected bone is often the first symptom. Bone destruction and infected pieces of bone, detached from healthy bone, can occur and those bone fragments may need to be operated. In the event of severe destruction, a pathological fracture may occur[5,6].

Pathological fractures of the femur in adults caused by osteomyelitis are rare consequences of this disease. The most common pathological fractures of the long bones in adults are due to a malignancy that has metastasized to the bones[7]. Haematogenous long bone osteomyelitis in adults who are not immunosuppressed is a very rare phenomenon and only few cases have ever been reported. This condition, which causes a pathological fracture, is even rarer because only a few reports have been found in the English medical literature. Cases of reciprocal femoral hematogenous osteomyelitis have not been reported, so we present a clinical case in which pathological fractures of both femurs occurred.

For the first time, a 46-year-old Caucasian male was referred to the hospital because of sudden pain, redness and hardening in the lateral side of the left thigh, and subfebrile fever, with no anamnesis of trauma/injury or immunosuppression. Three months after the onset of the first symptoms of osteomyelitis in the left thigh, the patient began to complain of right thigh pain.

Patient’s symptoms started two weeks ago with recurrent episodes of lateral side of left thigh, pain and swelling, which had been worsened the last 24 h.

At the second hospitalization, the patient stated that he had relapsed to pneumonia three months before the onset of the first symptoms of osteomyelitis, but there are no data on the pathological agent and the treatment applied, because patient was treated in other hospital. No evidence of immunosuppression was documented.

Redness and hardening in the lateral side of the left thigh.

During each hospitalization, blood analysis revealed a mild leukocytosis, significant thrombocytosis and moderately elevated C-reactive protein. The blood biochemistries, as well as urine analysis were normal. Increased partial CO2 was observed.

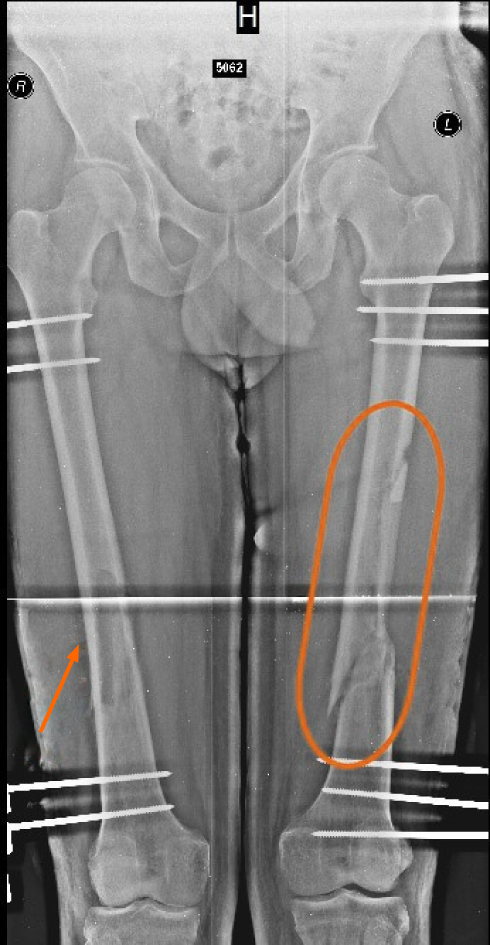

First hospitalization: During the first hospitalization, the patient underwent an X-ray showing the onset of left femoral destruction. A CT scan showed an abscess in the left thigh around the bone (Figure 1).

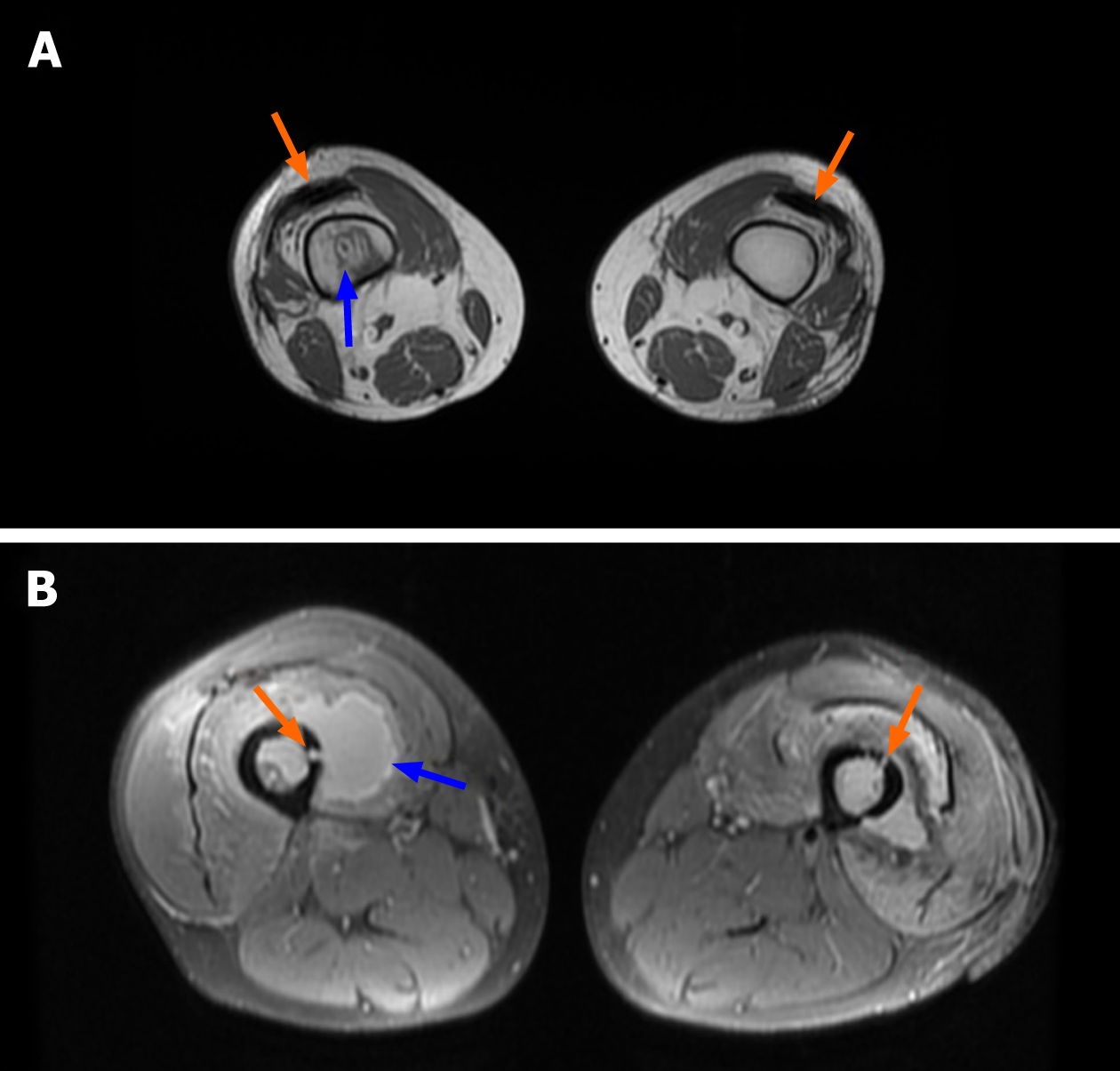

Second hospitalization: Three months after the first hospitalization symptoms recurred and patient was examined by an orthopaedist. Moreover, similar symptoms were seen in the right femur. Radiographs, MRI and CT scans were performed: Pathologic fracture of the left femoral diaphysis with displacement, osteomyelitis of the left femur, osteomyelitis of the right femur, sequester. The fistulogram showed a contrast flow broadly around the implant, the femoral region (Figure 2-4).

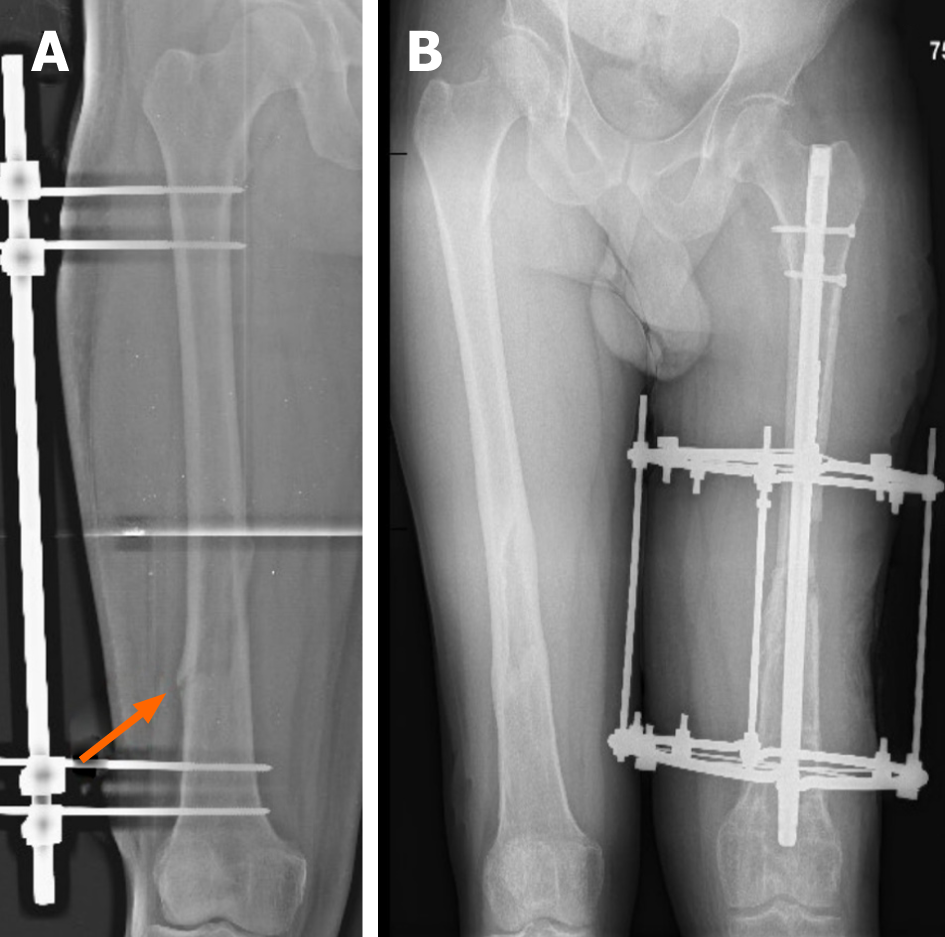

Third and fourth hospitalizations: An X-ray and MRI were performed during the third and fourth hospitalizations (Figure 5).

A thorough microbiological culture of the surgical materials (each time) from both thighs under anaerobic conditions was used to identify the pathogen Anaerococcus prevotii, sensitive to ampicillin and penicillin. It is believed that this pathogen is the main cause of the whole disease. Based on the history of pneumonia, it can be tentatively stated that it was also caused by this pathogen. The patient was also diagnosed with lung infiltrates and purulent processes on the molars, the same pathogen was extracted from the pus of the lungs. A mixed microflora was found during several hospitalizations, which we associate as a contributing b nosocomial infection.

Spontaneous reciprocal haematogenous osteomyelitis of the femurs and secondary abscesses on both thighs, sepsis.

During first hospitalization patient underwent abscessotomy and twice (in nine days interval) - an active wash. He was treated with antibiotics, but no significant improvement was observed and debridement surgery was performed.

Three months later, symptoms recurred and patient underwent postoperative wound excision, abscessotomy, debridement, femoral trepanation, and washes were performed on a regular basis. It was decided to perform external osteosynthesis of the left femur using external AO fixation. In order to prevent a pathological fracture in the right femur, it was decided to install the external AO fixation. One month later, a pathological fracture without displacement of the right femur occurred, when the patient fell (with external AO fixation). The surgery was performed and AO was switched to external fixation with the Ilizarov’s apparatus, which was left for half a year. Half a year later, the fracture completely healed, the device was removed, and the signs of osteomyelitis did not recur (Figure 5A).

Five days later, the patient’s condition worsened again, with secretion around the bars and severe pain of the left thigh. The patient underwent re-inoculation, debridement, and treatment with an intramedullary necklace of antibiotics. The external fixation with Ilizarov’s apparatus was formed again. After about 8 mo, the patient’s condition improved, he was seen by an orthopaedist on an outpatient basis, and it was decided to remove the proximal ring on the left side 9 mo after the last operation.

A month later, redness of the left thigh, intense pain and febrile fever occurred. Purulent discharge appeared around the bars. The patient was hospitalized in an Orthopaedic department and underwent four operations during hospitalization. Debridements, external fixation with Ilizarov’s apparatus, after improvement of the condition, and intramedullary osteosynthesis with silver-plated intramedullary nail were performed in the remission of the infection. Long-term antibiotic therapy with Meropenem and Penicillin was applied.

The last operation involved a left knee remodeling, a long-lasting passive knee motion machine, with flexion up to 100 degrees. The left leg was radiographically shorter by 5 cm due to femoral resection. Once the patient’s condition improved, he was discharged for outpatient treatment. At 2 mo after the last hospitalization, the patient sought emergency treatment for intense left knee and thigh pain, protrusion of a protruding propellant through the skin, and extensive wound secretion. In the radiographs performed, migration of the screws was observed. According to the patient, two days ago, at night, a screw had pierced the skin and he removed the screw himself. The patient underwent operative treatment - abscessotomy - with crop, biopsy, pathological examination. Due to the instability of the intramedullary nail, the distal femur was fixed by the external fixation with Ilizarov method with 2 rings.

The patient was discussed in the order of the consilium. He underwent removal of the intramedullary nail and external fixation apparatus and debridement on the left thigh were performed. After one month, repeated debridement and constant washing were performed, without any improvement. Debridement and external fixation with Ilizarov’s apparatus of the left knee joint and left femur were performed after a few days.

During that hospitalization, the patient underwent four reconstructive/plastic surgeries of the left thigh. Transplantation of free fibula into femur was performed. The postoperative period was repeatedly complicated by infectious complication, purulent secretion from the wound and fistula. The patient was discussed on a consilium basis - as all the possibilities to restore the femoral integrity were exhausted with persistent infection, significant bone integrity damage, widespread infection of the femur, knee contracture, and negative dynamics. It was decided to perform amputation of the left femur. After the operation, the condition was complicated by sepsis and the patient was treated in the intensive care unit for several days. Two cases of stump debridement, Meropenem and Colistin, have been used for the infection of the stump.

The right femur healed completely and the signs of osteomyelitis did not appear. Positive clinical effects were observed on the stump of the left thigh with the combination therapy applied, and the stump healed in the primary manner. The patient was discharged in a satisfactory condition for rehabilitation treatment. The patient is seen on an outpatient basis for about a year by an orthopaedist and all signs of osteomyelitis have disappeared.

Although usually osteomyelitis is caused by many predisposing factors, including age, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, drug abuse, various surgical implants, and immunodeficiencies, but sometimes we also have to deal with cases where patients have absolutely no risk factors. It is well known that the most common causes of osteomyelitis are bacteria[4]. They enter the bloodstream from the source of the infection in the body (pneumonia, oral cavity infection, urinary tract infection, etc.), are brought into the bone with the blood, and cause hematogenous osteomyelitis[8].

Surgical management in such cases is the cornerstone of therapy. Dead bone and foreign material must be removed, dead space must be managed with bone grafts, tissue flaps, or implanted antibiotic-impregnated material, and hardware should be removed unless absolutely necessary. When hardware is removed, antibiotic therapy should ideally be completed before new hardware is implanted. A one-stage approach with debridement alone or immediate re-implantation of hardware is less likely to achieve cure, though in specific circumstances these may be appropriate or necessary[9].

In this case, after the patient has developed pneumonia and denied all other possible causes of osteomyelitis, it can be said that the same pathogen (Anaerococcus prevotii) moved to the left femur by haematogenous pathway and caused osteomyelitis. Anaerococcus prevotii, a Gram-positive, anaerobic, indole-negative coccus, is a common isolate of the normal flora of skin, the oral cavity and the gut and can also be isolated from human clinical specimens such as vaginal discharges and ovarian, peritoneal, sacral or lung abscesses. A review of the medical literature in English has not reported a single case in which Anaerococcus prevotii caused hematogenous osteomyelitis complicated by pathological fractures in both femurs[10].

Significant thrombocytosis and increased partial CO2 were observed each time the patient was admitted to the hospital with an exacerbation. Thrombocytosis is characteristic of an inflammatory process or infection in the body, which in this case the patient had. Elevated partial carbon dioxide indicated that there is a suitable condition for this anaerobic bacterium. In the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) air inclusions in interfascial space, which are characteristic of an anaerobic agent, were observed[11]. In abscesses on both thighs, the purulent secretion had a particularly unpleasant odor and exuded with high pressure from medullary cavity (Figure 3).

When the patient underwent the first microbiological cultures from the punctate, a mixed microflora or individual other pathogens (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseu-domonas aeuruginosa, and others) were obtained, which could already indicate a possible contributing nosocomial infection.

Because of their fastidiousness, anaerobes are difficult to isolate and are often unrecognized. Delay in implementing appropriate therapy may lead to clinical failures. Their isolation requires proper methods of collection, transportation and cultivation of specimens. A single pathogen, the anaerobic bacterium Anaerococcus prevotii, which was most likely to be the cause of pneumonia, was recovered by several in-depth microbiological studies with proper transportation and the right conditions for growth. Also, it is important to mention that the patient relapsed after two years to another purulent lung infection during which surgery was performed, resected abscesses in the lungs and microbiological examinations isolated Anaerococcus prevotii[12]. At the same time, the patient experienced purulent processes in the roots of the molars, which we can associate with the manifestation of the same bacterium.

The question arises as to why it was the amputation of the left limb that helped the patient to fully recover or at least not to relapse throughout the year. First of all, the left femoral fracture occurred with displacement. Although the femoral fractures were brought together, proper osteosynthesis was performed, and healing did not occur. Secondly, the manifestation of the infection, resulting in purulent processes, led to the destruction of the bone and required a large number of surgeries, after which, unfortunately, the bone was shortened by five centimeters. Finally, prolonged immobilization and shortening of the bone resulted in knee contracture, which also did not contribute to proper bone healing.

In contrast to the left thigh, the onset of signs of osteomyelitis in the right femur was followed immediately by preventive measures such as fixation by the external AO fixation to prevent pathological fracture. Although the fracture occurred, thanks to the existing apparatus, it was without displacement and remained stable. This resulted in better bone healing and full recover. In addition, a clear pathogen (Anaerococcus prevotii) was already present in the right femur at the onset of symptoms, which was also identified during abscessotomy from the surgical material.

To sum up, hematogenous osteomyelitis is an insidious disease that spreads throughout the body at lightning speed and usually is not typical in adults. It requires an initial source of infection to develop, which has been observed in the patient in this case. After pneumonia, the pathogen traveled haematogenously to the left femur and caused osteomyelitis. Due to the complex identification of anaerobic bacteria and lack of initial anamnesis of former pneumonia, Anaerococcus prevotii was not detected immediately. In addition, other nosocomial infections contributed to the underlying disease, making it difficult to identify the pathogen.Based on the fact that a pathological fracture with a displacement on the left and destructive processes as a result of infection occurred, it all prevented the femur from healing. Unfortunately, after long and unsuccessful attempts, the only solution came from limb amputation and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, which, for the better, completely stopped the spread of the infection. Preventive fixation was performed in the right thigh, which, even after a pathological fracture, prevented the bone from displacing and the bone healed completely. It is now known that the patient is fully recovered and no longer shows signs of osteomyelitis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Lithuanian Society of Orthopedics and Traumatology; Nordic Orthopedic Federation; and European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Lithuania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Berber I, Smolić M S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Strecker W, Russ M, Schulte M. [Hematogenous osteomyelitis in adults]. Orthopade. 2004;33:273-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | García Del Pozo E, Collazos J, Cartón JA, Camporro D, Asensi V. Bacterial osteomyelitis: microbiological, clinical, therapeutic, and evolutive characteristics of 344 episodes. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31:217-225. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Arias Arias C, Tamayo Betancur MC, Pinzón MA, Cardona Arango D, Capataz Taffur CA, Correa Prada E. Differences in the Clinical Outcome of Osteomyelitis by Treating Specialty: Orthopedics or Infectology. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Calhoun JH, Manring MM, Shirtliff M. Osteomyelitis of the long bones. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23:59-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Osteomyelitis, NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Accessed Apr. 01, 2020. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/osteomyelitis/. |

| 6. | Raff MJ, Melo JC. Anaerobic osteomyelitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:83-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weber KL. Evaluation of the adult patient (aged >40 years) with a destructive bone lesion. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:169-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Osteomyelitis, Infectious Disease Advisor, Feb. 15, 2019. Accessed Apr. 03, 2020. Available from: https://www.infectiousdiseaseadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/infectious-diseases/osteomyelitis-4/. |

| 9. | Fritz JM, McDonald JR. Osteomyelitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36:nihpa116823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anaerococcus - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed Apr. 01, 2020. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/anaerococcus. |

| 11. | Thrombocytosis - Symptoms and causes, Mayo Clinic. Accessed Apr. 03, 2020 Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/thrombocytosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20378315. |

| 12. | Murphy EC, Frick IM. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci--commensals and opportunistic pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:520-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |