Published online Dec 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11504

Peer-review started: May 20, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: October 23, 2021

Accepted: November 29, 2021

Article in press: November 29, 2021

Published online: December 26, 2021

Processing time: 216 Days and 19.4 Hours

In older patients with comorbidities, hip fractures are both an important and debilitating condition. Since multimodal and multidisciplinary perioperative strategies can hasten functional recovery after surgery improving clinical outcomes, the choice of the most effective and safest pathway represents a great challenge. A key point of concern is the anesthetic approach and above all the choice of the locoregional anesthesia combined with general or neuraxial anesthesia.

Core Tip: In surgery for repairing hip fractures, often pain is adequately and safely managed through multimodal strategies without the use of regional analgesia techniques. However, especially in the elderly, the use of regional analgesia techniques as a part of a multimodal strategy for limiting systemic analgesics needs to be considered. Further research is warranted to establish the most effective peripheral regional technique.

- Citation: Crisci M, Cuomo A, Forte CA, Bimonte S, Esposito G, Tracey MC, Cascella M. Advantages and issues of concern regarding approaches to peripheral nerve block for total hip arthroplasty. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(36): 11504-11508

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i36/11504.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11504

We read the manuscript by Wang et al[1] with interest because it addresses a topic of paramount concern. In older patients with comorbidities, hip fractures are an important and debilitating condition. Worldwide, it is estimated that hip fractures affect approximately 18% of women and 6% of men[2]. Moreover, the direct costs of hip fractures are massive, considering the long period of hospitalization and subsequent rehabilitation[3].

To improve analgesia, facilitate mobilization and rehabilitation, reduce the risk of complications, such as deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, and decubitus ulcers, most fractures are surgically repaired. Currently, total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most successful orthopedic procedures performed. For patients with hip pain due to a variety of conditions, THA can relieve pain, restore function, and ameliorate the health-related quality of life (HR-QoL). Multimodal, multidisciplinary fast-track surgery, also known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), can hasten functional recovery after various types of surgical procedures[4,5]. ERAS protocols may result in reduced hospital length of stay and improved outcomes[6]. Notably, ERAS recommendations have been recently released about hip replacement surgery[7]. A summary of ERAS components specific to anesthesia for hip fracture is shown in Table 1.

| Preoperative | Preoperative multimodal analgesia should include regional anesthesia (e.g., femoral nerve block, fascia iliac block) and minimization of opioids use. |

| Maintain preoperative hydration. The routine administration of sedatives to reduce anxiety is not recommended. | |

| Avoid prolonged preoperative fasting and recognize gastric motility may be altered in patients with hip fractures. | |

| Intraoperative | Minimize PONV by using anesthetic techniques that reduce it (i.e., NA or TIVA), and drug prophylaxis. |

| Avoid anticholinergic and antihistamine as antiemetics in older patients, due to increased risk of confusion or agitation. | |

| Individualize fluid management. | |

| Use of tranexamic acid for reduced blood loss. | |

| Optimize glycemic control. | |

| Maintain normothermia. | |

| Postoperative | Use multimodal opioid sparing analgesic strategy including local infiltration analgesia, nonopioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs), and possibly tramadol. |

| Avoid any sedatives and respiratory depressants. | |

| Fast mobilization/rehabilitation. |

Preoperative multimodal analgesia should include regional anesthesia (e.g., femoral nerve block, fascia iliac block) and minimization of opioids use.

Maintain preoperative hydration.

The routine administration of sedatives to reduce anxiety is not recommended.

Avoid prolonged preoperative fasting and recognize gastric motility may be altered in patients with hip fractures.

Minimize postoperative nausea and vomiting by using anesthetic techniques that reduce it (i.e. neuraxial anesthesia (NA) or total intravenous anesthesia), and drug prophylaxis.

Avoid anticholinergic and antihistamine as antiemetics in older patients, due to increased risk of confusion or agitation.

Individualize fluid management.

Use of tranexamic acid for reduced blood loss.

Maintain good glycemic control.

Maintain normothermia.

Use multimodal opioid sparing analgesic strategy including local infiltration analgesia, non-opioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), and possibly tramadol.

Avoid any sedatives and respiratory depressants.

Fast mobilization/rehabilitation.

Options for anesthesia to repair hip fractures include general anesthesia (GA), NA, and peripheral nerve block (PNB), combined with GA or NA. On the other hand, epidural analgesia is not recommended[7]. The choice of the proper anesthetic technique should be based on patient comorbidities and the anticipated procedure. These patients are usually on anticoagulant/platelet therapy with the impracticability of a proper drug suspension for a safer neuraxial approach. Since mortality with hip fractures increases with the surgical delay, GA is often preferred to NA[8]. Although to date there is no high-quality evidence to recommend one technique over another[9], both approaches may involve hemodynamic issues, especially in complex patients[10]. Additionally, in patients who can receive either GA or NA, the latter is suggested[11]. When NA is not possible, PNB combined with GA offers multiple benefits, especially in the context of multimodal and ERAS strategies. Moreover, locoregional techniques are very versatile and, when used as a single-injection, PNB can be performed for analgesia even during positioning for the neuraxial technique[12-14]. Nevertheless, because it can limit early and safe mobilization, motor nerve block should be avoided[7].

As the authors reported, the perioperative pain control strategy through multimodal therapy is useful for minimizing the need for opioids. According to the recent PROSPECT guidelines, regional analgesic techniques or local infiltration analgesia are recommended, mostly when analgesics are contraindicated and/or or when severe postoperative pain is expected[15].

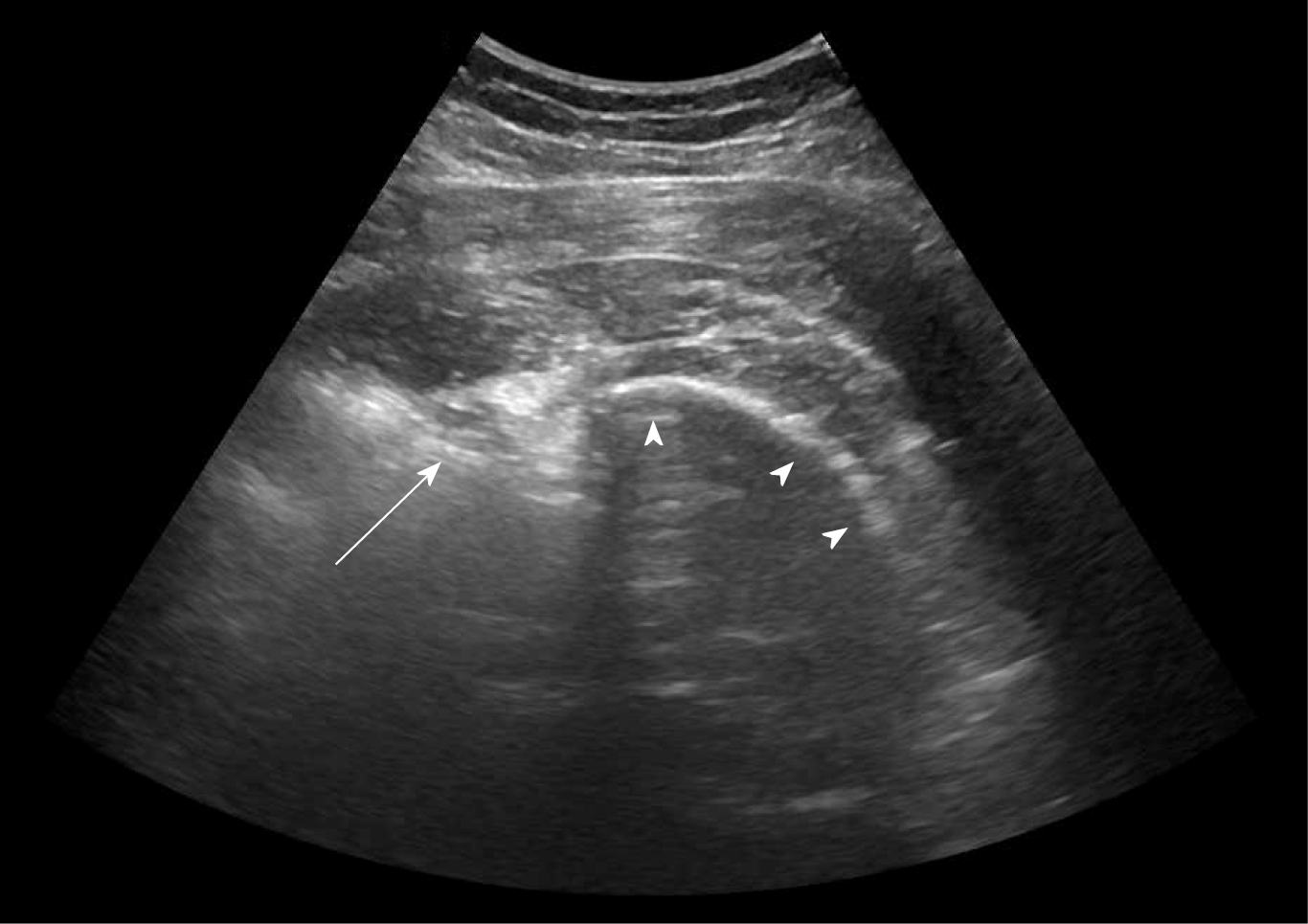

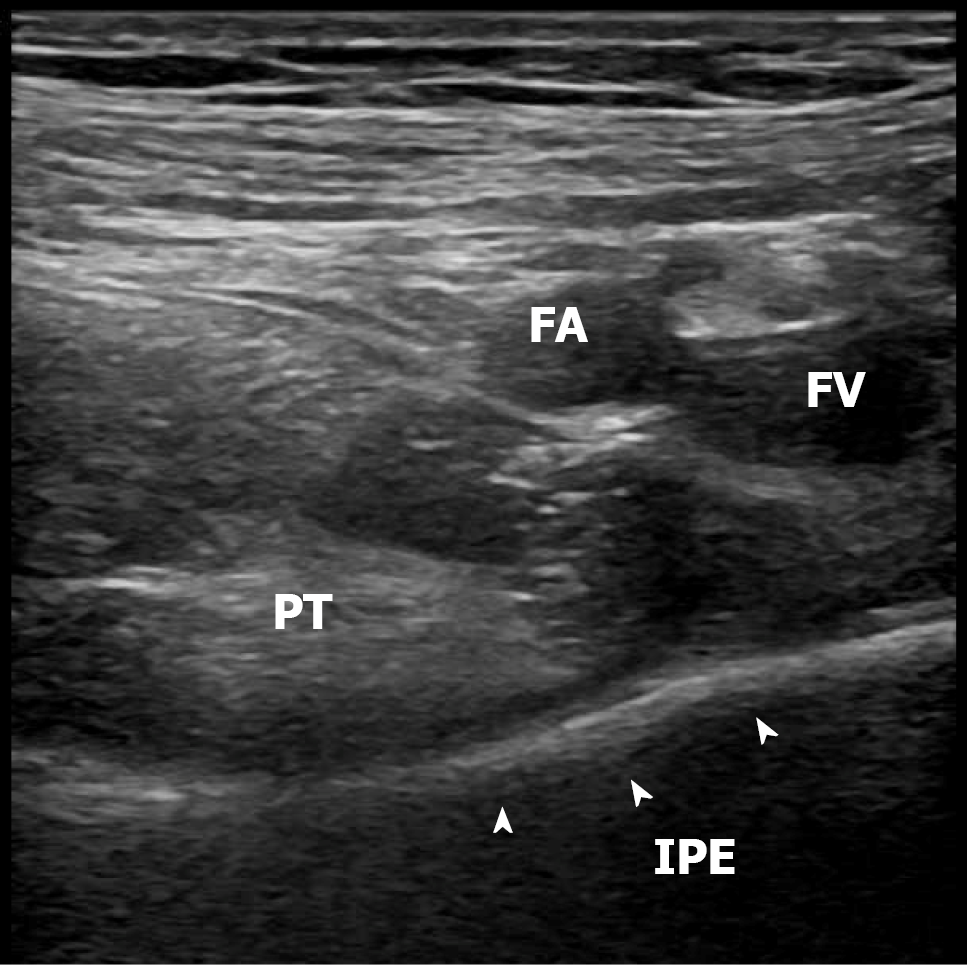

What is the most appropriate regional analgesic approach for PNB in THA? It appears that there are multiple options with the fascia such as the fascia iliac block, the lumbar plexus block, the sciatic nerve block (Figure 1), the pericapsular nerve group block (Figure 2), and others but none have shown to be superior[16,17]. In the context of THA, neurophysiology offers important knowledge. The hip joint is innervated by the femoral, the obturator, and the sciatic nerves. They also provide innervation to the whole leg, except for the lateral leg surface which is innervated by the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Consequently, no single nerve block can be used to provide complete analgesia after THA[12]. On this premise, although the authors demonstrated the failure rate of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block with direct suprainguinal injection for fascia iliac block is lower than that of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block in the fascia iliac compartment, for complete analgesia the obturator, accessory obturator, and sciatic nerve blocks need to be included. Therefore, in patients who received preoperative suprainguinal fascia iliac block, analgesia may not be optimal and, consequently, in Wang’s[1] retrospective study it was necessary to use opioids, both intraoperatively and postoperatively. Uncertainties remain about the most effective block to be used and, thus, further prospective studies comparing different locoregional analgesia techniques are needed.

Another important concern is the duration of postoperative analgesia. To facilitate rapid mobilization, and avoid the use of opioids, analgesia should be prolonged as much as possible. The use of ropivacaine combined with adjuvants such as dexamethasone, or alpha 2 agonists may prolong the duration of the analgesic effect and the effectiveness of the block. Nevertheless, because single-injection blocks, with or without adjuvants, rarely provide analgesia for more than 16-20 h, another strategy performed through continuous nerve blocks can be particularly helpful. However, attention must be paid to avoid a prolonged motor block.

In conclusion, we greatly appreciate the attempt made by the authors and, although their study has the limitations reported by the authors themselves, it can offer important suggestions for designing prospective studies and implementing scientific evidence. To date, because clinical advantages were not proven for nerve block techniques over other approaches not involving a motor blockade (e.g., local infiltration analgesia), the ERAS® Society recommendations limit the role of PNB in this type of surgery[7]. Thus, the search for optimal fascia block methods without any motor block is mandatory to build substantial recommendations, and for promoting safe and effective block-supported multimodal approaches. These methods include peripheral regional techniques. In particular, we suggest studying the use of the 4 blocks separately (i.e. proximal femoral nerve block or fascia iliac block, proximal obturator nerve block, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block, and posterior, parasacral sciatic nerve block) or the combined use of perineural catheters and NA (or GA) can lead to: (1) Reduced or avoided perioperative opioid use; and (2) Improved outcomes in terms of length of hospital stay, Harris hip scores, pain, and HR-QoL[18].

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oommen AT S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Wang YL, Liu YQ, Ni H, Zhang XL, Ding L, Tong F, Chen HY, Zhang XH, Kong MJ. Ultrasound-guided, direct suprainguinal injection for fascia iliaca block for total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective study. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:3567-3575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Veronese N, Maggi S. Epidemiology and social costs of hip fracture. Injury. 2018;49:1458-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Swayambunathan J, Dasgupta A, Rosenberg PS, Hannan MT, Kiel DP, Bhattacharyya T. Incidence of Hip Fracture Over 4 Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1225-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1147] [Cited by in RCA: 1190] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ficari F, Borghi F, Catarci M, Scatizzi M, Alagna V, Bachini I, Baldazzi G, Bardi U, Benedetti M, Beretta L, Bertocchi E, Caliendo D, Campagnacci R, Cardinali A, Carlini M, Cascella M, Cassini D, Ciotti S, Cirio A, Coata P, Conti D, DelRio P, Di Marco C, Ferla L, Fiorindi C, Garulli G, Genzano C, Guercioni G, Marra B, Maurizi A, Monzani R, Pace U, Pandolfini L, Parisi A, Pavanello M, Pecorelli N, Pellegrino L, Persiani R, Pirozzi F, Pirrera B, Rizzo A, Rolfo M, Romagnoli S, Ruffo G, Sciuto A, Marini P. Enhanced recovery pathways in colorectal surgery: a consensus paper by the Associazione Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani (ACOI) and the PeriOperative Italian Society (POIS). G Chir. 2019;40:1-40. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Soffin EM, Gibbons MM, Wick EC, Kates SL, Cannesson M, Scott MJ, Grant MC, Ko SS, Wu CL. Evidence Review Conducted for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery: Focus on Anesthesiology for Hip Fracture Surgery. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:1107-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wainwright TW, Gill M, McDonald DA, Middleton RG, Reed M, Sahota O, Yates P, Ljungqvist O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020;91:3-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 83.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Della Rocca G, Biggi F, Grossi P, Imberti D, Landolfi R, Palareti G, Randelli F, Prisco D. Italian intersociety consensus statement on antithrombotic prophylaxis in hip and knee replacement and in femoral neck fracture surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:1003-1010. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Van Waesberghe J, Stevanovic A, Rossaint R, Coburn M. General vs. neuraxial anaesthesia in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Messina A, Frassanito L, Colombo D, Vergari A, Draisci G, Della Corte F, Antonelli M. Hemodynamic changes associated with spinal and general anesthesia for hip fracture surgery in severe ASA III elderly population: a pilot trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013;79:1021-1029. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Soffin EM, Gibbons MM, Ko CY, Kates SL, Wick E, Cannesson M, Scott MJ, Wu CL. Evidence Review Conducted for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery: Focus on Anesthesiology for Total Knee Arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:441-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guay J, Kopp S. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11:CD001159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Diakomi M, Papaioannou M, Mela A, Kouskouni E, Makris A. Preoperative fascia iliaca compartment block for positioning patients with hip fractures for central nervous blockade: a randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39:394-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yun MJ, Kim YH, Han MK, Kim JH, Hwang JW, Do SH. Analgesia before a spinal block for femoral neck fracture: fascia iliaca compartment block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:1282-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anger M, Valovska T, Beloeil H, Lirk P, Joshi GP, Van de Velde M, Raeder J; PROSPECT Working Group* and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy. PROSPECT guideline for total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:1082-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bugada D, Bellini V, Lorini LF, Mariano ER. Update on Selective Regional Analgesia for Hip Surgery Patients. Anesthesiol Clin. 2018;36:403-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Badiola I, Liu J, Huang S, Kelly JD 4th, Elkassabany N. A comparison of the fascia iliaca block to the lumbar plexus block in providing analgesia following arthroscopic hip surgery: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2018;49:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Del Buono R, Pascarella G, Barbara E. General or neuraxial in the hip fractured patient? Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:269-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |